2

Infrastructure Management Practices and Organization

Management means, in the last analysis, the substitution of thought for brawn and muscle, of knowledge for folkways and superstition, and of cooperation for force. It means the substitution of responsibility for obedience to rank, and of authority of performance for the authority of rank.

—Peter F. Drucker, People and Performance

INTRODUCTION

The U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) has more than 50 major facilities in 35 states with a replacement plant value of more than $70 billion. These facilities are owned by the federal government but managed, operated, and maintained by contractors. Thus DOE has evolved into an organization with decentralized authority and responsibility, relying on contractors to achieve its facilities stewardship objectives. Oversight of the department’s facilities and infrastructure (F&I) has been delegated to seven program offices.

The U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) notes that:

Many of these [DOE] facilities are in poor condition, and others are reaching the end of their design life. For example, DOE’s national laboratories were built during World War II and the early Cold War. Over 60 percent of the laboratory space is more than 30 years old, and 35 percent is more than 40 years old. DOE has begun to receive funding from the Congress to improve its infrastructure, and its offices are developing plans for improvements. The cost of upgrading DOE’s infrastructure will exceed several billion dollars. DOE’s challenge will

be to spend this money effectively and efficiently, in a way that is consistent with its most important missions. (GAO, 2003, p. 25)

DOE has begun to address these issues by issuing new policies and procedures but, as noted in the committee’s preliminary report (NRC, 2004), implementation is inconsistent across the department and additional changes are needed at all levels to create and maintain a culture of effective and efficient facilities stewardship at DOE.

This chapter discusses both the cultural issues that shape DOE’s response to F&I management challenges and organizational issues that influence management decisions. Basic approaches to improving management processes and procedures are also discussed.

STEWARDSHIP CULTURE

Organizations that effectively manage F&I are characterized by a cultural understanding and communication of the strategic role that facilities and infrastructure play in achieving site missions and program objectives (NRC, 2004). The critical importance of DOE’s missions for the nation’s defense and well-being and for the advancement of science to benefit humanity make the stewardship of the real property assets that support these missions equally important. But the committee has observed a culture based on the premise that spending resources on F&I stewardship is done at the expense of program missions. On the contrary, the integration of mission at all levels and in all processes applies not only to F&I but also to environmental safety and health and community relations. Such functions are not competitors of program resources but rather enablers that make the program bigger and better than the sum of its parts. Proper integration of all support elements can only ensure program success. The department’s level of dedication to the establishment of a robust F&I stewardship culture for its real property assets will determine whether it has the capability to fulfill its missions now and far into the future.

Leadership

Strong leadership will be required to consistently embrace strategies of thoughtful planning and a long-term perspective for stewardship of DOE’s research laboratories and nuclear facilities. As stated in the 1998 NRC report Stewardship of Federal Facilities:

The ownership of real property entails an investment in the present and a commitment to the future. Ownership of facilities by the federal government, or any other entity, represents an obligation that requires not only money to carry out that ownership responsibility, but also vision, resolve, experience, and expertise to ensure that the resources are allocated effectively to sustain that

investment. Recognition of these obligations is the essence of stewardship. (NRC, 1998, p. v)

The four most important elements in creating a climate that encourages effective stewardship of facilities in federal agencies are:

-

Leadership by agency senior managers;

-

The establishment and implementation of a stewardship ethic by facilities program managers and staff as their basic business strategy;

-

Senior managers and program managers who create or seek incentives for successful innovative facility management programs; and

-

Agency strategic plans that give suitable weight to effective facilities management. (NRC, 1998, p. 63)

These statements stress the importance of a DOE culture that recognizes the strategic role of facilities and infrastructure in program success and that therefore takes full responsibility and accountability at all levels of the organization for the life-cycle management of F&I.

Because DOE is coming from a past of failed stewardship, the implication is that many behaviors and practices need to change in order to create a new culture that embraces its life-cycle responsibility for F&I (GAO, 2003). Not only do new directives and policies, such as RPAM (DOE, 2003a), need to be issued, but a new culture needs to be created and reinforced at all levels of the department.

Strategic Plan

The committee believes that the DOE 2003 strategic plan (DOE, 2003c) does not provide sufficiently clear focus to the role of F&I in achieving the department’s missions and that this lack of strategic focus may impede implementation of RPAM. The September 2003 strategic plan states that it establishes long-term goals, lays out strategies to achieve them, identifies key intermediate objectives along the way, and provides the basis for evaluating the department’s performance. However, these goals and objectives have not been applied to F&I. Because of the absence of a clear, consistent link between strategic goals and facilities stewardship, the performance of the department’s real property asset management is likely to receive less attention from senior managers and, consequently, managers at all levels.

The strategy for DOE’s nuclear weapons stewardship mission is an exception, in that the plan lists a key intermediate objective to develop and maintain the facilities and infrastructure necessary to ensure the safety, security, and reliability of the stockpile. However, the strategy for world-class scientific research states only that DOE will provide world-class research facilities, without recognizing the need to sustain and recapitalize those facilities. The plans for DOE’s other strategic goals include no recognition of the effort required to provide and maintain the facilities needed to achieve the goals. These observations are consistent

with the committee’s preliminary assessment (NRC, 2004), which noted the relatively strong F&I program of NNSA as compared to the other program secretarial offices (NRC, 2004). Although NNSA has not addressed every issue of integrating program and F&I management, it has taken steps to recognize F&I as a strategic enabler of its program. NNSA top management has initiated actions to improve the quality and consistency of F&I planning, budgeting, performance measurement, and auditing processes as a central resource to assist site operations in achieving excellence.

The 2003 DOE strategic plan includes commentary on achieving its stated goals, noting that: “In order to meet the Nation’s needs for cutting-edge science, the Department must periodically replace or make major upgrades to aging or outdated major experimental facilities. These requirements will be weighed against the benefits from cost-effective modifications to existing facilities to ensure that the maximum national benefits are derived from existing infrastructure” (DOE, 2003c, p. 39). However, this statement represents only part of what the committee believes is needed in the department’s strategic plan to ensure consistent life-cycle stewardship of its facilities. Facilities management and infrastructure renewal need to be recognized as critical to DOE’s achieving its goals and included as a key performance metric for the department. Consideration should therefore be given to adding a specific F&I strategic goal to the department’s four basic mission goals.1 This strategic goal should call for facilities and infrastructure to be planned, constructed, sustained, and recapitalized to support all departmental missions and for facilities and infrastructure that no longer support departmental missions to be disposed of safely, efficiently, and in a timely manner. The strategy should be further defined by establishing criteria for setting priorities, defining performance measures (discussed in Chapter 4), and setting performance targets. The strategic importance of F&I should also be visible in the department’s annual budget requests.

Delegation of Authority and Responsibility

In a December 15, 2003 memorandum from DOE Deputy Secretary Kyle McSlarrow (DOE, 2003b) to Robert Card, Under Secretary for Energy, Science, and Environment, and Linton Brooks, Under Secretary for Nuclear Security, the

deputy secretary delegated responsibility for implementing RPAM to the program secretarial offices (PSOs). The deputy secretary also stated that:

I am committed to improving the management of our real property assets. Successful implementation of the Order [RPAM] will enable the Department to better carry out its stewardship responsibilities, and will ensure that its facilities and infrastructure are properly sized and in a condition to meet our mission requirements today and in the future. I expect your leadership in implementation of RPAM within your organizations. (DOE, 2003b, p. 1)

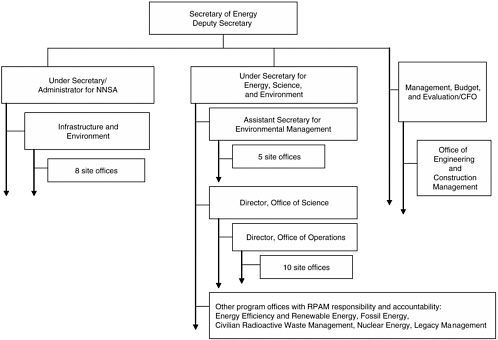

Although RPAM contains reporting and oversight requirements, the delegation of authority from the deputy secretary to the under secretaries, assistant secretaries, program managers, site managers, and federal facility managers raises issues that concern the committee. (See Figure 2-1 for a chart of RPAM F&I authority and responsibility.) The committee believes that even though authority is delegated, senior executives retain the ultimate responsibility for the effective implementation of RPAM through both reporting and ongoing evaluation of subordinates’ performance in achieving the desired goals. Effective evaluation will require the identification and implementation of effective metrics and their consistent application throughout the department. It should be abundantly clear that executives at the highest levels are ensuring life-cycle stewardship of DOE F&I.

Responsibility was described by Admiral H.G. Rickover as a unique concept that can reside in only a single individual. He noted that one may share it with others, but one’s responsibility is not diminished. It may be delegated, but it remains with the delegater; it may be disclaimed, but it cannot be divested. Once responsibility is rightfully assigned, no evasion, or ignorance, or passing of blame can shift the burden to someone else. Unless a senior manager can point a finger at the man or woman who is responsible when something goes wrong, then responsibility has never been assigned.

The committee believes that even with the delegation of authority, it is the responsibility of DOE leaders to ensure the department’s life-cycle stewardship of F&I. Issues such as the sufficiency, utilization, condition, and disposition of facilities need to be addressed at all levels of the department, beginning at the top. DOE reliance on contractor execution creates a situation where operational liabilities are shared among site contractors and federal employees. However, overall responsibility and accountability for the condition of F&I and for the general health, safety, and welfare of employees and the public will always fall back to DOE.

The committee observed that, in some cases, DOE site office employees have diminished authority and limited resources to direct the actions of contractors, resulting in a loss of continuity of authority in executing corporate directives. For example, at one of the sites visited by the committee, members learned that the DOE site staff had been told to discontinue directing the actions of the site contractors in an effort to avoid change order requests from the contractors. While this practice may have reduced short-term cost increases, the

long-term effect was to diminish the role and responsibility of DOE staff and to prevent the necessary control and influence traditionally embodied by DOE staff.

Consistent Implementation of Policies

As noted above, implementation of RPAM was delegated by the deputy secretary through his memorandum of December 15, 2003 (DOE, 2003b). The committee’s review of subsequent actions through March 2004 shows inconsistent implementation processes employed by NNSA, the Office of Science (SC), and the Office of Environmental Management (EM). While progress has been made by all programs, the inconsistencies reduce the overall rate of improvements that could have been achieved in the department’s management of real property assets. The committee is concerned that DOE’s plans for implementing RPAM lack complete guidelines, common metrics, and evaluation processes, and that training for federal facility managers is only in the pilot stage of development. The committee believes that a facilities management manual, detailing how to implement RPAM and the best process to achieve implementation success, could increase the rate of improvement of DOE facilities management. In the absence of an F&I management manual, a clear statement of the characteristics of excellence of performance should be made by senior DOE management.

Life-Cycle Stewardship

DOE’s current approach to life-cycle F&I stewardship is fragmented. The department assigns primary responsibility for facilities planning, development, and operations to site managers and contractors. Headquarters controls critical decisions for line item projects (greater than $5 million), but smaller projects and ongoing operations are delegated to site offices. Disposition of excess facilities is overseen by the site office, but a third party, EM (or the proposed Office of Future Liabilities), is responsible for the disposition of contaminated facilities.

This practice of multiple handoffs in F&I management contributes to a situation in which no one party is responsible and accountable for the overall success of the life-cycle stewardship of F&I. Indeed, the committee observed instances where the involvement of multiple PSOs, acting as the lead PSO or tenant, resulted in the failure of stewardship responsibilities. For example, at the NNSA Y-12 site, there is a contaminated excess laboratory that had been an SC facility but there are no plans for SC, EM, or NNSA to undertake the necessary disposition of the facility; and at the Savannah River Site, the lead PSO (EM) had no plans for the long-term needs of the NNSA facilities that have an ongoing mission on the site. (EM has only recently recognized its responsibilities as the site lead PSO to maintain the facilities’ mission readiness for tenants that will use the site after EM’s mission is completed.)

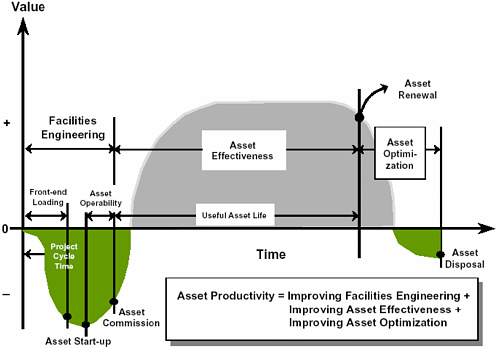

The committee has observed that successful corporations in industry, such as

DuPont, have a more integrated view of managing the facility life cycle. DuPont’s definition of responsibility for facilities, from inception through demolition, recognizes the detailed management attention needed during the entire life cycle and that decisions made at any one point in the facility’s life cycle will affect future actions (DuPont, 1996). DuPont’s approach also ensures that existing assets are properly maintained, renewed, and utilized, and that construction of additional assets is approved only after existing facilities are evaluated and there is a clear business case for the new assets. An annual review ensures that all facilities add value, or that they are prioritized for revitalization or elimination. See Figure 2-2, Asset Life Cycle, for an illustration of DuPont’s approach to facilities life-cycle management.

The 1998 NRC report Stewardship of Federal Facilities noted that:

An owner is responsible for funding not only planning, design, and construction, but also maintenance, repair, replacement, alterations, and normal operations, such as heating, cooling, and lighting, and finally, demolition. Failure to recognize these costs and provide adequate maintenance and repair results in a shorter service life, more rapid deterioration, and higher operating costs over the life cycle of a building….

The full life cycle costs of new facilities are considered in the current federal

FIGURE 2-2 Asset life cycle. SOURCE: E.I. du Pont de Nemours and Company. Copyright © 2004, reprinted with permission of E.I. du Pont de Nemours and Company.

budget process…. The costs of designing and constructing a new facility, then, may receive considerable scrutiny during budget hearings, but the budget process is so structured that 60 to 85 percent of the total costs, the cost of operating and maintaining the facility, do not receive the same scrutiny. Thus, the federal budget process is not structured to consider the total costs of facilities ownership. (NRC, 1998, pp. 13-14)

DOE, like other federal agencies, is faced with developing its own policies and procedures to address its life-cycle F&I stewardship responsibilities.

The objective of the previous DOE asset management policy, Order 430.1A, Life-Cycle Asset Management (LCAM) (DOE, 1998), which was replaced by RPAM, was that the management of physical assets from acquisition through operations and disposition be an integrated and seamless process linking the various life-cycle phases. Although DOE failed to fully achieve the LCAM objective the committee believes the objective is still valid. RPAM focuses on management procedures and performance measures but it also needs to consider the desired outcome—that is, effective life-cycle F&I stewardship.

ORGANIZATIONAL STRUCTURE

At DOE, the functions of facilities and infrastructure management are currently dispersed throughout the organization, with responsibilities distributed among the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA), the Office of Science (SC), and the Office of Environmental Management (EM), which each have responsibility for multiple sites and have been the focus of this assessment. Other programs that have direct F&I responsibilities defined in RPAM include the Office of Fossil Energy, the Office of Civilian Waste Management, the Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy, the Office of Nuclear Energy, Science, and Technology, and the Office of Legacy Management. The Office of Management, Budget, and Evaluation (OMBE) and the Office of Engineering and Construction Management (OECM) have no direct F&I management responsibility but provide departmental policy and staff support functions. The committee believes that DOE’s asset management is adversely influenced by the diverse approaches to F&I inherent in this broad decentralized organization.

The central organization in DOE for F&I issues is OECM. OECM developed the RPAM and is currently responsible for the following functions:

-

maintaining the Condition Assessment Survey (CAS), Condition Assessment Information System (CAIS), and Facilities Information Management System (FIMS),

-

developing training materials,

-

observing and reviewing PSO activities, and

-

developing reports for senior managers based on FIMS data.

However, critical F&I functions such as the implementation of RPAM, the identification and deployment of best practices, development of performance measures and targets, determination of budget targets and allocation of resources, and quality control and oversight have been delegated to the PSOs and to their respective site offices. The result is that DOE F&I management activities are fragmented and implemented with varying degrees of effectiveness.

Centralized facilities management allows a decision maker to set priorities across all sites in order to maximize performance of the entire complex, whereas decentralization of facilities management often results in independent decisions based on factors unrelated to mission-based facilities needs. In industry, a facility’s funding could be based on the leadership’s influence in the organization or on the current success of a product in the marketplace. Neither of these factors has anything to do with the condition of the facility or life-cycle stewardship. In DOE similar decision making may occur based on the prominence of a project. A centralized approach to decision making places the strategic direction for the facilities at a single point. The M&O contractors can deal with the tactical and operational decisions; however, DOE should not delegate the strategic, mission-critical decisions that depend on centralized facilities management.

Comparison of Organizational Models

A recent study by the Corporate Executive Board’s Real Estate Executive Board, entitled Aligning the Real Estate Organization: Enabling Fast Response to Business Needs (CEB, 2004), concluded that the design of the corporate real estate (CRE) organization is a key factor in meeting a number of current challenges facing the CRE executive, including alignment with business needs, cost reduction, and efficiency enhancement. All of these items are also critical to the success of DOE programs. In choosing the optimal organizational design, the CRE executive needs to decide on the appropriate level of centralization and strike a balance between functional and regional alignment. The governance spectrum runs from fully centralized to fully decentralized, with a hybrid model in the middle. The study found that 64 percent of companies are primarily centralized in their CRE organizations, with 22 percent hybrid and only 14 percent decentralized. Furthermore, the vision for the future estimates those numbers at 77 percent, 14 percent, and 8 percent, respectively.

The trend of the corporate approach to F&I management is clearly toward the centralized and functional CRE model, which allows companies to:

-

easily map decisions to corporate needs and strategies (i.e., overall DOE strategies and objectives),

-

leverage economies of scale,

-

enforce consistent decision-making procedures,

-

provide global perspective and develop best practices across business units and geographies,

-

develop core competencies, and

-

assist regional or local operations with centralized resources.

The U.S. Navy’s Commander of Naval Installations Command (CNI) is an example of a government organization that has reaped the benefits of stronger central F&I authority. The Navy recently undertook initiatives that resulted in unifying the installations and service providers under a single installation management organization that is responsible for shore installation support to the fleet. The mission of CNI is “to provide consistent, effective and efficient shore installation services and support to sustain and improve current and future fleet readiness and mission execution” (Navy, 2003). This centralized responsibility has reduced redundancies and established clear operational control of resources by creating a single responsible office that is an advocate and point of contact for naval shore installations, and by integrating management of the 16 naval regions, including 98 naval activities around the world, into one central structure for resource policy and business guidance. DOE could also look to DuPont, which supports a mature facilities and infrastructure organization that focuses on achieving desired results in DuPont’s financial performance by clearly aligning F&I performance with the corporate mission.

Successful private corporations, such as DuPont, place the authority and responsibility for F&I at the level of senior vice president. At DOE, the deputy secretary is the departmental chief operating officer and is therefore the senior responsible authority for institutional accountability for addressing management issues and leading transformational change (GAO, 2004). For DOE’s F&I issues, the deputy secretary’s responsibilities should include: strategic planning; oversight of compliance with key directives and orders; tracking and documentation of management performance for all DOE facilities; definition of key operating metrics and benchmarks; training of an adequate, qualified F&I management staff; and assistance to the secretary in the evaluation of the competency and performance of key DOE personnel and contractors. The deputy secretary has delegated most of the day-to-day responsibilities for the policy and oversight activities to OECM while the PSOs have been delegated the direct responsibility for implementing F&I stewardship. Thus, in order to elevate the strategic importance of F&I in DOE and improve the level and consistency of F&I performance, the committee believes that OECM should be strengthened (i.e., given additional responsibility, authority, and resources) to encompass including the following:

-

Analysis and review of data used in FIMS and CAIS;

-

Review and interpretation of CAS data;

-

Planning and implementation of F&I projects as a unified effort across all

-

PSOs to support funding and performance of DOE’s entire facilities complex;

-

Establishment of specific metrics to be used in evaluating the performance of all PSOs using consistent criteria;

-

Preparation of specific guidelines relating to consistent implementation of RPAM;

-

Promotion of significant and meaningful sharing of best F&I management practices across all PSOs;

-

Periodic audits relating to essential performance measures reported by the site management teams;

-

Development and/or refining of policies and procedures for the purpose of creating durable and long-lasting directions and implementation of F&I management; and

-

Oversight to ensure that existing and new facilities support DOE’s missions, are fully justified, and are developed efficiently by employing rigorous life-cycle and project management methods.

These functions should be undertaken by qualified personnel with multidisciplinary experience and expertise in facilities management, environmental management, energy and utility services, and capital acquisition projects. OECM’s authority in ensuring consistent application of best practices should be unequivocal.

Facilities and Infrastructure Executive Steering Committee

The DOE Facilities and Infrastructure Executive Steering Committee (FISC) was established to guide the overall direction of real property asset management in the department and promote the resolution of cross-program issues. FISC is composed of senior-level representatives of the DOE program offices that have responsibilities for real property assets. It is sponsored and coordinated by OECM by virtue of a departmental charter that expires in 2004.

The committee reviewed the FISC charter and it is the committee’s opinion that FISC should continue to serve as an executive-level action arm to assist with implementation and ongoing support for RPAM. The steering committee could also be the primary vehicle for implementing the actions discussed in this report. FISC should continue to be led by OECM in a strengthened and fortified position with senior representatives from all PSOs, and should continue to employ ad hoc working groups. The committee also believes that FISC needs to be chartered as a standing committee with performance measures to assess its success. Best practices, once identified, reviewed, and accepted by FISC (probably through an appropriate working group), should become DOE standard practice and not subject to further debate by program offices, sites, and contractors.

PROCESS IMPROVEMENT

In reviewing the management history of DOE, the committee found that many excellent management concepts related to facilities and infrastructure stewardship were developed and issued in the form of orders to field offices, but that they did not result in any significant change in F&I performance (DOE, 2000). The process of issuing policies is limited as an effective communication tool and change agent. For DOE to succeed in addressing its facilities and infrastructure challenges, it needs to articulate the problems, identify possible solutions, develop partnerships and create opportunities for collaboration among managers at all levels, develop training and provide tools, monitor progress, and provide incentives for participation and consequences for nonparticipation. RPAM provides a structure but meaningful change will require action.

Human Capital and Knowledge Management

RPAM specifies that “a qualified DOE Federal facilities management staff must be assigned at cognizant headquarters offices and field elements to provide for implementation of this Order and to ensure accountability” (DOE, 2003a, p.16). However, the order does not identify the qualification requirements and therefore each office will determine its own version of what is required. OECM is responsible for managing the certification program for DOE project managers and real estate specialists and has prepared a draft RPAM certification course. It appears logical that OECM should also be responsible for establishing department-wide qualification requirements for facilities management at all levels.

For ongoing support of practices to improve real property asset management, the committee believes it is important that the organizations and individuals charged with the implementation of RPAM also be charged with developing a qualified DOE federal facilities management staff and that they have the support of DOE senior management for this effort. The committee also believes the OECM is well positioned to take the responsibility to lead this effort. Three initiatives should be implemented to foster this support.

-

A facilities management forum for facilities managers and program officials to reach consensus on issues such as performance measures;

-

A process to identify and promulgate best practices to be mandated for use across DOE; and

-

A facilities management training and career development program.

Facilities Management Forum

The committee believes that a critical part of creating a successful facilities management community is a vibrant facilities management forum for the discus-

sion of new facilities management ideas as well as a mechanism to promote the health and growth of the community. A facilities management forum is a platform for facilities managers and program officials to reach consensus on issues such as the skills needed by DOE employees and contractors. It is also an excellent mechanism for individuals to seek assistance for tackling difficult issues. As mentioned previously, the committee believes that OECM should be the organization to host such a forum and that FISC should be involved in its development.

Best Practices

The committee believes that OECM should develop processes and procedures to identify best facilities management practices and promulgate them across DOE. Without these processes and a facilities management forum, the transfer of successful practices is unlikely to occur, thus reducing significantly the effectiveness of efforts to improve F&I management at DOE. The need for such an effort is justified by the significant variation in the maturity and competence of facilities management capabilities among the DOE sites visited by the committee. Continued implementation of RPAM could be enhanced with minimal effort if the effective practices and processes established at some of the labs were implemented throughout the department. For example, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) was one of the labs selected as a pilot site for a cost-effective maintenance management program in response to a congressional mandate to provide models for improving facilities management in the DOE. In August 2003, LLNL issued its Pilot Program Report (LLNL, 2003), which identified the practices and processes used along with management accomplishments. The most promising practices identified by LLNL are listed below:

-

A single system for counting and categorizing real property inventory;

-

A single valid engineering-based system for assessing facility conditions with adequately trained personnel and multiple levels of review;

-

Prioritized budget allocations based on physical conditions, mission relevance, life-cycle costs, and budgets;

-

Charges to users of an annual maintenance fee based on the number of square feet used;

-

A real property maintenance budget controlled by a central office with power to shift resources to facilities in the greatest need;

-

A maintenance system for correcting low-value deficiencies and conducting preventive maintenance;

-

Training and certification of facility and project managers; and

-

Training for leadership development.

The committee was impressed with the management initiatives undertaken at LLNL toward establishing effective processes and practices, and with the progress

made in their implementation. While much has yet to be accomplished to overcome past problems, the effects and accomplishments to date have improved the situation significantly. The committee believes that the early implementation of RPAM throughout DOE would be enhanced if all department sites used LLNL practices and processes as models. Although some specific LLNL activities, processes, and tools may not be directly applicable to all DOE sites, the committee believes they should be considered for adoption and adapted as necessary. If the LLNL program activities are to be considered for DOE-wide use there will need to be more documentation and training for new users.

As mentioned previously, the committee believes that OECM is well positioned to coordinate the development of mechanisms to effectively identify best practices and rapidly communicate them to those charged with facilities stewardship at DOE. The committee also urges that the use of clearly established “best practices” be mandated. A best practice is one that has been reviewed, vetted, and accepted by FISC for use throughout DOE. Thus its use throughout the department should not be subject to frther program review and debate.

Facilities Management Career Path

A formalized training program that meets the technical and management needs of the positions involved and a designated career path that defines the training and experience needed for advancement are essential to the long-term implementation of RPAM. The committee is encouraged by the progress made by OECM in establishing the draft RPAM Course (PMCE 07), which will assist in providing consistent and repeatable RPAM implementation throughout DOE. The committee believes that this training effort should be expanded to establish a core facilities management curriculum and a facilities manager career path similar to the Project Management Career Development Program (PMCDP).2 Such a curriculum could be used to train personnel for the various levels of facilities management assignments at headquarters and in the field. More importantly, this effort could provide DOE with the required cadre of facilities management professionals, knowledgeable in DOE processes and procedures, to move among the various government positions.

In providing the oversight required of facilities stewardship, the committee believes that professional licensing is an important mechanism that could be used by DOE to raise the credentials, stature, and credibility of facilities engineering staff. Just as the PMCDP defines the qualifications for various levels of project

management responsibilities, DOE should define the qualifications for planning, evaluating, and managing F&I and ensure that federal and contractor personnel are qualified to undertake their assigned tasks.

FINDINGS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Finding 2a. DOE is coming from a past of failed stewardship of its facilities and infrastructure and has begun to address this challenge through new policies and procedures, but implementation is inconsistent across the department. Strong leadership will be needed to overcome the impediments caused by decentralized and dispersed responsibility and by reliance on contractors to achieve the department’s facilities stewardship objectives. A successful F&I stewardship culture needs management at all levels to take ownership and responsibility for addressing the life-cycle requirements for F&I. DOE leaders need to ensure that the department’s missions are supported by its facilities and infrastructure.

Recommendation 2a. DOE needs to inculcate a facilities stewardship culture that embraces a central management approach to ensure that:

-

There is a clear understanding and acceptance of the strategic role of F&I in program mission performance and success;

-

There are well-defined performance measures for facilities management that are tied to the achievement of strategic goals;

-

Sufficient guidance is provided for efficient and effective implementation of policies and procedures;

-

DOE and its contractors take ownership and responsibility for addressing the life-cycle requirements for F&I;

-

The best practices and principles are adopted and applied at all levels of DOE and are integrated into departmental policy and procedures;

-

The allocation of roles and responsibilities between DOE and its contractors is clearly defined, and managers at all levels are held accountable; and

-

DOE employees and contractors are trained to meet or exceed their performance requirements.

Finding 2b. The DOE 2003 strategic plan does not provide sufficiently clear focus to the role of F&I in achieving the department’s missions and this lack of strategic focus may impede the effective implementation of RPAM. There is an absence of a clear, consistent link between strategic goals and facilities stewardship.

Recommendation 2b. DOE’s strategic plan should include a facilities and infrastructure goal that is applicable to all missions. The plan should include a vision that encompasses the goal of quality performance as well as supporting activities, including both project and F&I management. The goal should also include performance targets.

Finding 2c. The trend of the private corporate approach to F&I management is toward centralized and function-defined organizations. Following the current trends in corporate asset management, the roles of DOE central staff organizations need to be strengthened.

Recommendation 2c. In order to increase central control and elevate the strategic importance of F&I, OECM’s responsibilities, authority, and resources should be strengthened.

Finding 2d. The Facilities and Infrastructure Executive Steering Committee (FISC) was established in early 2002. This committee could serve as a valuable executive-level action arm to assist with implementation and support for RPAM.

Recommendation 2d. FISC should be reestablished as a standing committee and led by OECM. The consensus nature of the existing charter should be modified so that once best practices are identified, reviewed, and accepted by FISC they become standard practices throughout the department.

Finding 2e. In the recent past DOE has issued orders setting forth many excellent management concepts related to F&I stewardship. But these orders have not resulted in any significant change in F&I performance. It is important that those charged with the development of processes and procedures have the support of DOE senior management and the resources to initiate change. In order to manage change, DOE needs to identify performance measures and performance targets to define success, address a wide spectrum of parameters that are relevant to all stakeholders, and provide the means for programs to succeed.

Recommendation 2e. The committee recommends three initiatives to support F&I process improvement. OECM should identify appropriate process metrics (as discussed in Chapter 4) and managers at all levels should be held accountable for performance.

-

A facilities management forum for facilities managers and program officials to reach consensus on issues such as performance measures;

-

A process to identify and promulgate best practices (such as those documented in the LLNL pilot program) to be mandated for use across DOE; and

-

A facilities management training and career development program.

REFERENCES

CEB (Corporate Executive Board). 2004. Aligning the Real Estate Organization, Enabling Fast Response to Business Needs. Washington, D.C.: Corporate Executive Board.

DOE (U.S. Department of Energy). 1998. Life-Cycle Asset Management (Order O 430.1A). Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Energy.

DOE. 2000. Challenges in Asset Management. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Energy.

DOE. 2002. Management Policy for Planning, Programming, Budgeting, Operation, Maintenance and Disposal of Real Property (Policy P 580.1). Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Energy.

DOE. 2003a. Real Property Asset Management (Order O 430.1B). Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Energy.

DOE. 2003b. Memorandum from Kyle E. McSlarrow, Deputy Secretary; Subject: Order O 430.1B, Real Property Asset Management. December.

DOE. 2003c. The Department of Energy Strategic Plan: Protecting National, Energy, and Economic Security with Advanced Science and Technology and Ensuring Environmental Cleanup. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Energy.

DOE. 2004. Acquisition Career Development Program (Order O 361.1A). Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Energy.

DuPont. 1996. Asset Optimization Process. Wilmington, Del.: E.I. du Pont de Nemours and Company.

GAO (Government Accountability Office). 2003. Major Management Challenges and Program Risks: Department of Energy (GAO-03-100). Washington, D.C.: U.S. General Accounting Office.

GAO. 2004. High-Performing Organizations: Metrics, Means, and Mechanisms for Achieving High Performance in the 21st Century Public Management Environment (GAO-04-343SP). Washington, D.C.: U.S. General Accounting Office.

LLNL (Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory). 2003. Pilot Program Report; Site Planning and Facility Maintenance Management at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. Livermore, Cal.: Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory.

Navy. 2003. Flagship. Vol. 12, No. 29. Available online at http://www.flagshipnews.com/archives_2003/oct022003_1.shtml. Norfolk, Va.: Commander Navy Region Mid-Atlantic. Accessed July 8, 2004.

NRC (National Research Council). 2004. Preliminary Assessment of DOE Facility Management and Infrastructure Renewal. Letter report. February. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press.

NRC. 1998. Stewardship of Federal Facilities: A Proactive Strategy for Managing the Nation’s Public Assets. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press.