6

Water Quality Improvement: Institutional and Financial Solutions

Water quality problems and issues in southwestern Pennsylvania are both local and regional as evidenced by a variety of reports included in Appendix B, water quality assessments by the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection (PADEP), and testimony received by the committee. Some of these water quality problems are associated primarily with urbanization in the immediate Pittsburgh vicinity; some are associated with activity in the Monongahela and Allegheny River basins; still others are common to the predominantly rural counties in southwestern Pennsylvania. Large differences exist among the sources of problems, their potential effects on public health and environmental quality, and their likely solutions. Further, resolution of water quality issues in southwestern Pennsylvania is affected by other regional issues such as transportation, land use, and governance of the metropolitan area.

The existing pattern of water supply and water quality services in the region is highly fragmented, with more than 1,000 providers operating in the multicounty region. In Pittsburgh’s metropolitan area, like many other metro areas in the United States, large-special purpose authorities such as the Allegheny County Sanitary Authority (ALCOSAN) can achieve substantial economies of scale through joint management agencies. Although private organizations may not have direct voting power in what mix of organizations is chosen to implement the plan, they could very well influence how the public and its elected and appointed representatives make these choices. Although no single unit of government has all the necessary power to implement the Three Rivers Comprehensive Watershed Assessment and Response Plan (CWARP) recommended and discussed in Chapter 5, it is desirable to have some mechanism to facilitate continued oversight of regional progress (or lack thereof) toward clean water and its relationships to other regional goals and activities, and to help southwestern Pennsylvania realize the benefits of cooperation.

Furthermore, the situation is not static. Although the Pittsburgh metropolitan statistical area (MSA) is among the few in the nation to actually lose population during the 1990s (1.5 percent; see Chapter 2 for further information), it is nevertheless listed by American Rivers (2002) as among the top 20 metropolitan areas in terms of “urban sprawl.” This ranking is based on the percentage increase in developed land in 1997 compared to 1982. According to American Rivers,1 the Pittsburgh MSA experienced an increase of 42.5 percent in urbanized land, accompanied by a decrease in average density of 35.5 percent over those 15 years. Planning for water quality improvement, especially where capital investment is substantial, must therefore reflect regional planning goals concerning economic development and demographic character, such as impacts of urban sprawl and (re)development.

|

1 |

American Rivers is a national nonprofit conservation organization dedicated to protecting and restoring natural rivers; see http://www.amrivers.org for further information. |

Finding the right mix of existing and new organizations that best fulfill the necessary conditions for planning, implementation, and oversight of CWARP will be a difficult and time-consuming process. Several options that the region should consider are discussed in this chapter. The discussion begins with a review of management functions necessary to deliver water supply and water quality services and criteria for evaluating alternative organizational arrangements to perform those functions. The challenge is to find the right mix of organizations that can perform the necessary functions in an efficient and politically accountable manner. The committee’s examination of specific arrangements begins with existing organizations in the region. This is followed by a brief review of what other regions with somewhat similar problems have done. Future options for water resource and quality management in southwestern Pennsylvania are then explored. These options are discussed in light of existing enabling legislation and what additional legislation may be desirable. Also, two other significant factors influencing the choice of organizational arrangements are discussed: (1) potential sources of financing and (2) financial burdens that may be imposed on citizens of the region.

CRITERIA FOR EVALUATING ORGANIZATIONAL OPTIONS

Choosing an appropriate organization or set of organizations to address regional water quality problems holistically is a complex task. Criteria for guiding the formulation and evaluation of alternative arrangements usually include consideration of the following:

-

efficiencies with which each organizational arrangement could carry out the various policy-making and management functions by exploiting economies of scale;

-

geographic coverage sufficient to incorporate significant hydrological, biological, and chemical processes between upstream and downstream elements of the water resource system and to incorporate significant linkages in construction and operation of infrastructure that crosses political boundaries;

-

capacity to integrate water systems, wastewater systems, stormwater systems, and other aspects of water resources with land use and transportation;

-

legal, technical, and financial capacities of each option to perform management functions;

-

capacity of each option to involve the many faces of the public and minimize conflict in decision making processes; and

-

the nature of existing contracts and other commitments.

Before these criteria can meaningfully be applied, it is appropriate to describe the management functions, scale, and authorities of alternative arrangements.

Management Functions

A list of water quality planning and management functions for water systems is provided in Box 6-1. They are listed in approximate order of statutory authority necessary to perform them, beginning with the least intrusive government power and concluding with the most intrusive. Collection of data, planning, and technical assistance require only modest statutory authority. Implementing actions including financing, construction, taking of land, and adoption and

|

BOX 6-1

|

enforcement of regulations require substantially greater authority. General-purpose local governments, including municipalities and counties, usually have the broadest array of powers delegated to them by state legislatures. Therefore, they tend to face fewer legal obstacles, exercise greater power to integrate land use and water services, and have greater flexibility to implement economically efficient management programs within their limited geographical jurisdictions.

Issues of Scale

Scale is a key factor in selecting an appropriate mix of organizations to deliver services in the region. The National Research Council (NRC) Committee on Watershed Management (NRC, 1999) addressed the issue of choosing an appropriate scale for planning that includes all relevant hydrologic linkages, commenting as follows:

Managing water resources at the watershed scale, while difficult, offers the potential of balancing the many, sometimes competing, demands we place on water resources. The watershed approach acknowledges linkages between upland and downstream areas, and between surface and ground water, and reduces the chances that attempts to solve problems in one realm will cause problems in other…Organizations for watershed management are most likely to be effective if their structure matches the scale of the problem.

Planning at the watershed scale offers the opportunity to address externalities among several parties within the basin.

That earlier NRC committee addressed the problem of incorporating hydrologic and biological interdependencies that exist in water resource systems. Unfortunately, the geographic jurisdictions of organizations with the range of necessary legal authorities seldom match watershed boundaries. For example, Figure 5-2 shows about a dozen watersheds that contribute stormwater runoff to the contiguous urban area in and adjacent to Allegheny County and the City of Pittsburgh. There are approximately are parts of five counties and 100 municipalities within that area alone. New organizational arrangements may have to be created to effectively and efficiently manage water, but development of these arrangements may entail difficult political decisions that involve the transfer of some powers and responsibilities from existing units of government. These difficulties

must be weighed against the anticipated economy-of-scale benefits that new organization(s) may offer.

As discussed in Chapter 5, planning and management are needed to address the array of water resource problems at four interrelated scales in (and beyond) the Pittsburgh region, and organizational arrangements should be responsive to each of the following scales:

-

river basin, to address issues related to imports and exports to the multicounty region, including areas and states outside southwestern Pennsylvania;

-

multicounty/metropolitan scale, where decisions are being made about large-scale infrastructure and related land use in southwestern Pennsylvania that affect water resources and where opportunities exist to achieve efficiencies and avoid conflicts in regional water management;

-

urban areas in and around Allegheny County and outlying urban centers, where combined and separate sewer overflows and stormwater runoff must be addressed (see Figure 6-1); and

-

rural areas within southwestern Pennsylvania having problems of inadequate human waste disposal and water supply.

CURRENT SITUATION IN SOUTHWESTERN PENNSYLVANIA

Water quality management in the Pittsburgh region is highly fragmented, with responsibilities and authority distributed among a very large number of general purpose local governments, special districts, regional planning organizations, and the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. For purposes of this discussion, the region is defined by the nine-county area served by the Southwestern Pennsylvania Commission (SPC). It is important to note that alternative definitions (e.g., 11 counties; see Box 1-2) are discussed elsewhere in this report.

General Purpose Local Governments and Special Districts

The 2002 Census of Governments2 lists 526 general purpose governments within the region, distributed by county and type of government as shown in Table 6-1. In the 1997 Census of Governments,3 boroughs, cities, and municipalities were lumped together under the heading “cities” (the number of cities in the 1997 census is the same as the sum of boroughs plus municipalities plus cities in the 2002 census), and the numbers were unchanged from 1997 to 2002. Under Pennsylvania law, each of those local governments and the nine counties are authorized to provide water supply and sewer services.

In addition to the general purpose governments, there are 154 special districts engaged in either sewer service alone or both water supply and sewer service. The special districts are distributed by county, type, and characteristics of service boundaries as shown in Table 6-2. The only special districts included in the 1997 list of “large” districts in the Census of Government finances that were clearly identifiable as delivering sewer services were the Pittsburgh Water and Sewer Authority, with an annual expenditure of about $118 million, and ALCOSAN, with

|

2 |

See http://www.census.gov/govs/www/cog2002.html for further information on the 2002 Census of Governments. |

|

3 |

See http://www.census.gov/prod/gc97/gc971-1.pdf for further information on the 1997 Census of Governments. |

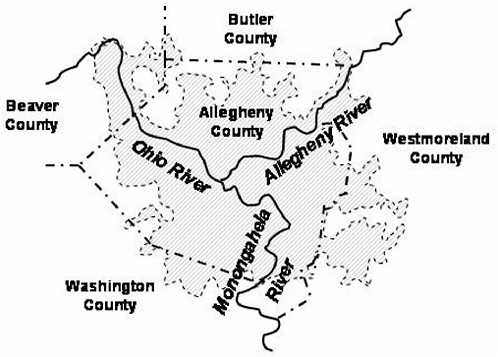

FIGURE 6-1 Approximate area of the urban core of southwestern Pennsylvania.

SOURCE: U.S. Census Bureau, http://ftp2.census.gov/geo/maps/urbanarea/-uaoutline/UA2000/ua69697/.

TABLE 6-1 General Purpose Local Governments in Southwestern Pennsylvania in 2002

|

County |

Cities and Boroughs |

Municipalities |

Townships |

|

Allegheny |

80 |

6 |

42 |

|

Armstrong |

16 |

1 |

28 |

|

Beaver |

27 |

2 |

22 |

|

Butler |

23 |

1 |

33 |

|

Fayette |

16 |

2 |

24 |

|

Greene |

6 |

0 |

20 |

|

Indiana |

14 |

0 |

24 |

|

Washington |

33 |

2 |

32 |

|

Westmoreland |

36 |

8 |

21 |

|

Total |

251 |

22 |

246 |

|

SOURCE: United States Census of Governments, 2002, http://www.census.gov/govs/www/cog-2002.html. |

|||

TABLE 6-2 Special Districts Providing Water and Sewer Service in Southwestern Pennsylvania

|

County |

Type of Service |

Type of Boundary |

||||

|

Sewer |

Water Supply and Sewer |

County |

Borough, City, or Township |

Within Countya |

Cross-County |

|

|

Allegheny |

27 |

5 |

2 |

7 |

12 |

3 |

|

Armstrong |

6 |

4 |

1 |

2 |

4 |

1 |

|

Beaver |

21 |

7 |

1 |

4 |

7 |

0 |

|

Butler |

6 |

4 |

0 |

0 |

4 |

4 |

|

Fayette |

15 |

2 |

1 |

4 |

5 |

1 |

|

Greene |

5 |

3 |

1 |

3 |

2 |

0 |

|

Indiana |

4 |

3 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

|

Washington |

21 |

2 |

1 |

10 |

6 |

1 |

|

Westmoreland |

24 |

2 |

0 |

5 |

7 |

4 |

|

Total |

122 |

32 |

10 |

37 |

49 |

16 |

|

a Within county but not limited to borough, city, or township. SOURCE: United States Census of Governments, 1997, http://www.census.gov/prod/gc97/gc-971-1.pdf. |

||||||

expenditures of $284 million annually. ALCOSAN serves 83 communities, most of which are located in or immediately adjacent to Allegheny County (see Figure 1-1).

Fragmentation of sewer services in the region with its many special districts reflects the general pattern of special districts in Pennsylvania. The 1997 Census of Governments reported 2,004 single-purpose sewer districts in the United States; Pennsylvania had the highest number, 591, about 30 percent of the nation’s total. Wisconsin was the next highest state with 320 single-purpose sewer districts.

Regional Planning Organizations

The Southwestern Pennsylvania Commission (SPC)4 is the officially designated regional planning agency for the area in and around Pittsburgh. SPC’s major role is “comprehensive regional planning with emphasis on transportation and economic development.” It was designated in 1974 as the metropolitan planning organization for transportation (MPO; see more below). It is also the Economic Development District for southwestern Pennsylvania, as designated by the U.S. Appalachian Regional Commission and the U.S. Department of Commerce. The SPC governing board includes more than 60 members representing the 10 counties, the City of Pittsburgh, the Governor’s Office, and several state and federal agencies. In addition to its primary functions, recent discussions regarding regional land use and growth decisions have pointed to the need for SPC to help address local development issues (e.g., WSIP, 2002). As a result, SPC is expected to continue to create, organize, and support public forums that bring a regional perspective to issues such as housing, sewer systems, and community development.

In 1998, SPC requested that the Western Division of the Pennsylvania Economy League5 make a preliminary study of the region’s needs. That study pointed to water supply and wastewater problems as potential impediments to future economic growth, and in 1999, the Western Division of the Pennsylvania Economy League initiated the Southwestern Pennsylvania Water and Sewer

|

4 |

For further information about the SPC, see http://www.spcregion.org. |

|

5 |

For further information about the Western Division of the Pennsylvania Economy League, see http://www.pelwest.com. |

Infrastructure Project (WSIP). The steering committee for that project included 60 public and private sector leaders from the region. As described elsewhere in this report (see also Appendix B), the WSIP report identifies several important water supply and wastewater management problems in the region, including the following:

-

overflowing sewers and failing septic systems that annually discharge billions of gallons of inadequately treated or untreated sewage into the region’s streams and lakes;

-

lack of clean and reliable water supplies to some residents, particularly in rural areas;

-

inadequate water and sewer infrastructure at otherwise desirable development sites; and

-

growth limitations in many communities resulting from inadequate facilities.

The WSIP Steering Committee recommended the following:

-

the SPC serve as the organization for setting regional water-related goals and priorities;

-

that the Three Rivers Wet Weather Demonstration Program (3RWW) serve as the regional organization for public education and technical assistance, expanding its service area beyond the ALCOSAN area that it now serves; and

-

that the Southwestern Pennsylvania Growth Alliance and the Greater Pittsburgh Chamber of Commerce serve as a regional advocacy organization.

These recommendations reflect a perspective from a knowledgeable leadership group within the region of the overall need to enhance regional water planning in southwestern Pennsylvania. The committee agrees with this need, and alternatives for meeting it are discussed later in this chapter. With its traditional focus essentially limited to economic development and transportation, SPC has not yet undertaken “comprehensive regional planning” that includes effective water planning.

Commonwealth of Pennsylvania

The Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection (PADEP) is the state regulatory agency charged with water quality management. In that capacity it has jurisdiction over those portions of the Ohio River basin within Pennsylvania, including the Allegheny and Monongahela River tributaries (see Box 1-2 and Figures 2-1 and 2-2). The PADEP has included the Ohio River basin among six major basins in the state (the others being Lake Erie, Genessee, Susquehanna, Potomac, and Delaware). Unlike water resource planning under Pennsylvania’s Water Resources Planning Act (WRPA) of 2002 (General Assembly of Pennsylvania, 2002), PADEP does not have a planning program to guide management of water quality at the basinwide scale.

The PADEP has, however, established a watershed restoration program at a smaller scale than the Ohio River basin under its nonpoint source program—Pennsylvania’s response to requirements of Section 319 of the federal Clean Water Act. The Unified Watershed Assessment was begun in 1998 to set priorities for restoration of streams where quality had been degraded by a variety of pollution sources other than municipal and industrial wastewater treatment plants and discharges. Included among sources are acid mine drainage, sewer system overflows, agricultural runoff, and other nonpoint sources (NPSs) of pollution. This program used PADEP’s 305(b) report (PADEP, 2002a) and its 303(d) list (PADEP, 2002b) of impaired streams as a starting point. The PADEP has delineated 104 watersheds that cover the entire state, 30 of which are located in the Ohio

River basin in southwestern Pennsylvania. Each watershed was initially assigned to one of four categories (see Table 6-3) based on the percentage of stream miles assessed, the percentage of these miles judged to be impaired, and the potential for NPS pollution.

Priorities for water quality improvement were assigned to each of the 23 watersheds in Pennsylvania that fall into Category I. Watershed Restoration Action Strategies (WRASs) were then developed for priority watersheds in cooperation with federal, state and local agencies; watershed-based organizations; and the general public. Included among the 30 watersheds in the Ohio River basin for which a WRAS has been prepared are the following (see Figure 6-2): Redbank Creek, Conemaugh River/Blacklick Creek, Stony Creek/Little Conemaugh River, Lower Youghiogheny River, Upper Youghiogheny River/Indian Creek, Upper Monongahela River, Raccoon Creek, and Chartiers Creek.

Each watershed plan includes descriptions of geology and soils, natural and recreational resources, and streams classified by PADEP as being of “exceptional or high quality.” Sources of water quality impairment are also discussed. Existing restoration initiatives are listed, and funding needs (to the extent they are known) are estimated. Funding from multiple sources has been provided to address some of the problems covered by these plans. Grants from Pennsylvania Growing Greener, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA’s) Section319 and Section 104(b)3, and Pennsylvania’s Watershed Restoration Assistance Program have all been received to fund restoration projects. The Pennsylvania Infrastructure Investment Authority (PENNVEST; see also footnote 8) also has made loans to local governments to address some of the problems. The PADEP Bureau of Abandoned Mines has also been an active participant in the implementation of many of these watershed plans. Table 6-4 summarizes some of the commitments already made to four of the eight watersheds listed above.

The watershed plans address important issues as identified in Pennsylvania’s most recent 305(b) report (PADEP, 2002a) and 303(d) list (PADEP, 2002b) for priority watersheds (see Chapters 3 and 4 for further information), but there is no assurance that streams in these watersheds will be restored to a level that fully supports their designated uses. Section 319 requires adoption of best management practices for NPS pollution, but unlike the total maximum daily load (TMDL) process (see also Chapters 3 and 5), it does not require a demonstration using predictive models or other evidence that water quality standards will be achieved. Follow-up investigations of projects in WRAS plans will be required to assess progress toward the goal of fully restoring streams in those watersheds.

TABLE 6-3 Pennsylvania State Water Plan Watershed Categories

|

Category |

Stream-Miles Assessed |

Assessed Miles Impaired |

Other Criteria |

|

I |

≥ 20% |

≥ 15% |

High potential for NPS pollution |

|

II |

≥ 20% |

< 15% |

— |

|

III |

Pristine |

— |

— |

|

IV |

Insufficient data |

— |

— |

|

SOURCE: PADEP, www.dep.state.pa.us. |

|||

FIGURE 6-2 State-delineated watersheds in southwestern Pennsylvania. NOTE: Shows two counties (Clarion and Jefferson) not included in the study area (see also Box 1-2).

SOURCE: Data from PADEP, www.dep.state.pa.us.

Contaminated water supplies and improper disposal of sewage from on-site sewage treatment and disposal systems (OSTDSs) not connected to public water or sewer systems were identified in the 2002 WSIP report as being of major concern in the region, but the Unified Watershed Assessment did not include a systematic evaluation of the extent of these problems. As discussed in preceding chapters, better information is needed to make an informed assessment of the locations, magnitude, and priorities to be assigned to these water quality problems.

In contrast to PADEP’s WRAS program, which focuses on priority problems within selected watersheds, water supply is being addressed on a basinwide scale that recognizes linkages among watersheds. Pursuant to the WRPA of 2002, PADEP has initiated the process to update the State Water Plan. That act establishes a Statewide Water Resources Committee (SWRC) to set guidelines and policies for the planning process and to conduct a formal review and approval of the product. Regional water resources committees are to be established for each of the state’s six major basins. After conducting an open public process and consulting with the SWRC and PADEP, the Ohio Basin Committee is to recommend regional plan components to the SWRC. These areas would be

TABLE 6-4 Select Restoration Activities of the PADEP Bureau of Watershed Management’s Watershed Restoration Action Strategy

|

Subbasin |

Problem |

Funding Source |

Number of Projects |

Project Expenditures (dollars) |

|

Redbank Creek watershed (Allegheny River) |

Abandoned mine drainage |

Pennsylvania Growing Greener Grants |

7 |

$570,000 |

|

EPA Clean Water Act Section 319 Grants |

2 |

$156,000 |

||

|

Stonycreek River and Little Conemaugh River watersheds |

Abandoned mine drainage, Upgrade or expand water supply, sewers, and wastewater treatment |

Pennsylvania Growing Greener Grants |

17 |

$1,508,000 |

|

EPA Clean Water Act Section 319 Grants |

7 |

$1,014,000 |

||

|

Pennsylvania Watershed Restoration Assistance Program |

2 |

$54,500 |

||

|

|

PADEP Bureau of Abandoned Mine Reclamation |

4 |

$2,755,000 |

|

|

EPA Clean Water Act 104b3 |

3 |

$518,000 (grants) |

||

|

PENNVEST |

4 |

$5,607,000 (loans) |

||

|

Upper Youghiogheny River |

Abandoned mine drainage |

Pennsylvania Growing Greener Grants |

3 |

$1,371,000 |

|

|

EPA Clean Water Act Section 319 Grants |

4 |

$587,000 |

|

|

Pennsylvania Watershed Restoration Assistance Program |

1 |

$261,000 |

||

|

Chartiers Creek watershed |

Point and nonpoint pollution, combined sewer overflow, abandoned mine drainage |

Pennsylvania Growin Greener Grants |

10 |

$497,000 |

|

|

EPA Clean Water Act Section 319 Grants |

7 |

$476,000 |

|

|

Pennsylvania Watershed Restoration Assistance Program |

1 |

$29,300 |

||

|

EPA Clean Water Act 104b3 |

1 |

$49,200 |

||

|

Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources Rivers Conservation Grants |

3 |

$178,000 |

||

|

PENNVEST |

3 |

$3,030,000 (loans) |

||

|

SOURCE: PADEP, www.dep.state.pa.us/dep/deputate/watermgt/wc/Subjects/Nonpointsourcepollution/Initiatives/Wraslist.htm. |

||||

designated, “critical water planning areas,” and identified on a multimunicipal watershed basis. Areas in which demand is expected to exceed supplies would be so designated, and more detailed critical area resource plans, or “water budgets,” would be established.

The WRPA does not have a similar mandate for water quality. Nevertheless, the planning process it establishes for water supply provides an excellent opportunity for PADEP to exert administrative leadership to better integrate water quality and water supply into a broader framework of planning for water resources at the basin scale. Basin plans should at a minimum indicate the water quality effects on public water supplies and the water quality effects of flood control activities.

Significant legislation enacted by the Pennsylvania General Assembly in 2000 could influence water planning among neighboring local governments. Among other provisions, Pennsylvania Acts 67 and 68 of the 1999-2000 legislative session, Article XI state the following:

For the purpose of encouraging municipalities to effectively plan for their future development and to coordinate their planning with neighboring municipalities, counties and other governmental agencies, and promoting health, safety, morals and the general welfare…powers for the establishment and operation of joint municipal planning commissions are hereby granted.

Local governments were given additional powers to regulate growth. Included in those powers were authority to limit development in specially designated “growth areas” and to implement a program of transferable development rights. Municipalities were given authority to enter into intergovernmental cooperative planning and implementation agreements. Municipalities located within the county or counties were also enabled to enter into intergovernmental cooperative agreements to develop, adopt, and implement comprehensive water resource plans for entire counties or any area within counties. Such agreements also enabled participating municipalities to share tax revenues and fees.

The legislation also included incentives for municipalities to enter into such agreements. State agencies were directed (1) to consider multimunicipal plans when reviewing applications for the funding or permitting of infrastructure or facilities, and (2) to consider giving priority to applications for financial or technical assistance for projects consistent with the county or multimunicipal plan.

Former Pennsylvania Governor Ridge issued an executive order in January 1999 directing PENNVEST to take land use into consideration when evaluating water project proposals; Acts 67 and 68 of 2000 had similar implications. Among other actions, PENNVEST established as an eligibility requirement that funding of proposed projects be consistent with applicable municipal, multimunicipal, or county comprehensive land use plans and zoning ordinances (see http://www.pennvest.state.pa.us/pennvest/cwp/ for further information). How effective this incentive will be in promoting cooperation remains to be seen.

WHAT OTHERS HAVE DONE

Southwestern Pennsylvania has many problems of water planning, delivery of services, and governance in common with other regions of the country. Knowledge and discussion of similar experiences in some of these regions may be instructive to those who will make decisions in the Pittsburgh region.

Metropolitan areas across the United States have adopted a variety of arrangements to perform water management functions that transcend boundaries of local government. These

arrangements range from consolidation of city and county governments to intergovernmental contracts. In the middle of this range are special purpose service districts.

Consolidation of City and County Governments

Consolidation of city and county governments has been adopted in Jacksonville-Duval County, Florida; Nashville-Davidson County, Tennessee; Indianapolis-Marion County, Indiana; and Louisville-Jefferson County, Kentucky. Such an arrangement has several advantages. It offers opportunities to capture economies of scale in capital investments, operating expenses, and administration. General purpose local governments, such as counties and municipalities, are empowered not only to exercise the water quality functions listed in Box 6-1, but also to integrate them with comprehensive land use and other aspects of urban development. Consolidation of city and county governments has the further advantage that both entities remain politically accountable for their actions.

In Cities Without Suburbs, David Rusk (1995) argues that establishment of a metropolitan government is much better than alternative strategies that seek to make multiple local governments act like a metropolitan government. He contends that regions where that possibility is most viable are those in which a central city could be consolidated with suburban communities within a single county that would include at least 60 percent of the total metropolitan population. Such criteria are satisfied in Pittsburgh-Allegheny County. Consolidation would not address all water quality problems in the region, but it would offer the benefits of economies of scale, incorporation of upstream-downstream linkages, incorporation of infrastructure linkages among neighboring political jurisdictions, enhanced comprehensive planning and management within the urban core, and a strong and more flexible financial base with greater employment capability.

Louisville-Jefferson County, Kentucky, is a case of city-county merger that leaders in the Pittsburgh region may want to examine more closely. The City of Louisville and Jefferson County governments were merged, effective January 2003. Like the Pittsburgh region, Louisville and Jefferson County were served by a large special purpose sewer district. The Metropolitan Sewer District (MSD) was formed in 1946 to provide sewer services across municipal boundaries for the metropolitan area. After the merger, it remained as a separate unit of local government, but its eight-member board is now appointed by the newly formed Metropolitan Council, the elected local government for Louisville-Jefferson County. The MSD also created the Louisville and Jefferson County Regional Sewer Corporation to provide services to a portion of neighboring Oldham County and a state facility in Shelby County.

There are about 680 miles of combined sewers with 115 combined sew overflow (CSO) outfalls in a heavily urbanized area of more than 38 square miles in Louisville-Jefferson County. According to the MSD, the agency began to address CSO-related water quality problems in the early 1980s, beginning with mapping and modeling of the collection system. Monitoring was initiated in 1991, and a long-term control plan was developed as required by the EPA’s 1994 CSO policy (see Chapter 5 for further information). Several infrastructure improvement projects have since been implemented, including in-line storage, separation facilities, storage basins, and pilot CSO treatment facilities (EPA, 2001). The MSD has also instituted a backup prevention program to eliminate damage to homes where stormwater creates surcharges on combined sewers. MSD also operates a stormwater utility.

At the larger, multicounty scale, the Kentuckyiana Regional Planning and Development Agency (KIPDA) is the MPO for the Louisville area, with jurisdiction over seven counties in Kentucky and two in Indiana. KIPDA’s primary responsibilities are transportation, social services, and public administration. Like SPC in the Pittsburgh region, KIPDA historically has had a very limited capability in water planning.

Kentucky’s Department of Environmental Protection adopted a watershed-based management approach in 1997. Five groupings of river basins and minor tributaries were identified, and assessments of these basins are made on a five-year rotating schedule. Reports generated for the Salt River and Minor Ohio River Tributaries include a 1998 status report, a 1999-2000 strategic monitoring plan, a 2001 assessment report, and a 2002 priority watershed reports. Although these reports provide substantial information about water quality in the area, they do not appear to provide very specific action plans. For those watersheds within Jefferson County, deference appears to have been given to watershed management activities initiated by the MSD.

Multiple-Purpose Metro Councils

A variant on general-purpose metropolitan government is multiple-purpose metro councils that are operating agencies as well as planning agencies. This option delegates limited authority held by general-purpose local governments to regional agencies that better match appropriate scales for water quality management. Examples of strong regional mechanisms with powers beyond planning are those in Portland, Oregon; the Twin Cities (Minnesota) Metro Council; and the Atlanta Regional Transportation Authority.

The Twin Cities Metro Council (TCMC) was created by the Minnesota state legislature in 1967 to coordinate planning and development in the seven-county metropolitan area. Through a series of additional acts, three separate agencies—the Metropolitan Transit Commission, the Regional Transit Board, and the Metropolitan Waste Control Commission—were merged into a single agency. The TCMC is governed by a 17-member council, with 16 members each representing a geographic district. All members are appointed by the Minnesota governor subject to confirmation by the state legislature.

In addition to its planning functions, the TCMC operates the region’s largest bus system, collects and treats wastewater, provides affordable housing, and acquires and funds a regional park system. The TCMC’s wastewater collection and treatment services are operated through its revenue-funded Environmental Services Division (ESD),6 which operates 8 wastewater treatment plants, treating about 300 million gallons per day from more than 2 million residents in 103 communities. It acts as a wholesale supplier of wastewater collection and treatment services to those communities, which in turn provide retail services to their customers. The TCMC also provides direct services to some customers. The ESD is also active in NPS pollution management and conducts monitoring and planning for stormwater runoff.

|

6 |

For further information about the ESD, see http://www.metrocouncil.org/services/environmental.htm. |

Special Districts

Several metropolitan areas have addressed intergovernmental management through the formation of special districts. Yaro (2000), reflecting on the history of service delivery in New York, argues that given the very limited acceptance of the formation of metropolitan governments, attention should be focused on more modest initiatives such as regional service districts. He observed that shortly after the five boroughs were consolidated to form the city in 1898, growth and development continued at a rapid pace beyond the boundaries of the enlarged city. Within two decades, and with no prospect for further expansion of city boundaries, the leadership created several new special-purpose authorities that transcended existing city limits. Among them were the Port of New York Authority (1921), toll road and bridge authorities (beginning in 1931), the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (1968), several regional park commissions in the 1920s, and the Interstate Sanitary Commission (also in the 1920s). Similar approaches have been used with success (and some failures) in many other metropolitan areas. Notable examples in Pittsburgh are ALCOSAN (1954; see Chapter 2 for further information) and the Port Authority of Allegheny County (1956), which operates the regional mass transit system.

Special districts of this kind are important in the delivery of sewer services throughout the United States. Of $26.7 billion spent by local governments in 1997, as reported by the U.S. Census Bureau, $5.3 billion (22 percent) was spent by special districts. An analysis of data from the 1997 Census of Governments indicates that 12 other U.S. metropolitan areas were served by special sewerage districts comparable to ALCOSAN with expenditures in excess of $50 million. Those that provide both sanitary sewer and combined sewer services are listed in Table 6-5. Notably, all of them serve core urban areas within metropolitan statistical areas (although very few serve an entire MSA).

Several factors should be considered when evaluating the option of a special district for water management that serves significant portions of a metropolitan area, including its

-

relationship to comprehensive regional planning;

-

capacity to integrate planning and management of public water supply, wastewater collection and treatment, combined sewer overflow, stormwater management, and aspects of the water resource system; and

-

relationship to general-purpose local governments within its service area.

The relationship between a special district and the regional comprehensive planning process can be important. All metropolitan areas throughout the country have some form of regional planning as mandated by various federal initiatives. For example, under the authority of the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1962, the Bureau of Public Roads required the formation of planning agencies to carry out the mandated planning for urban areas. At about the same time, the Housing and Urban Development Act of 1965 established a grant program to encourage the formation of MPOs to be controlled by elected officials from the jurisdictions they serve. The role of MPOs was strengthened by the Intermodal Surface Transportation Efficiency Act of 1991 (ISTEA) and further reinforced by provisions of the Transportation Efficiency Act (TEA-21) passed in 1998. As noted previously, SPC is the designated MPO for the Pittsburgh MSA.

TABLE 6-5 Selected Special-Purpose Districts in Metropolitan Areas

Rusk (2000) argues that with the new investments in transportation under TEA-21, MPOs will largely determine the growth and shape of urban areas, providing an impetus for regional land use planning. That is especially true in metropolitan areas such as Pittsburgh, where new transportation arteries are influencing the shape of development and this development affects both the supply and the demand for water-based services.

Milwaukee is a model of a metropolitan area with both strong regional planning and a large special sewer district. Regional planning is conducted by the Southeastern Wisconsin Regional Planning Commission (SEWRPC), established in 1960 as the official area-wide planning body for a seven-county urbanized and urbanizing area. Its scope includes planning and design of public works systems, such as highways, transit, sewerage, water supply, and park and open space facilities. SEWRPC has also been progressive in its regional approaches to flooding, air and water pollution, natural resource deterioration, and changing land use. The Milwaukee Metropolitan Sewer District (MMSD) is the special sewer service district.

The SEWRPC has been quite active in water quality planning as well as regional land use and transportation systems. Since 1990, SEWRPC has among its other activities produced a stormwater management plan for the MMSD service area. It has also produced about 40 geographically specific subarea, watershed, and lake management plans.

The capacity of a special district to integrate the multiple elements of water resource management is also important. As evidenced in part by Table 6-5, most large special sewer districts like ALCOSAN serve a central city and many outlying communities in a single county. It is especially important in areas with a CSO problem that a solution to this problem not create additional problems for separate stormwater or sanitary sewer systems. Notably, only two of the six special-purpose districts shown in Table 6-5 have jurisdiction over both.

The effectiveness of a special district may well be determined by its relationship to general-purpose local governments within its service area. An example of what can be accomplished with strong cooperation between a special district and its constituent communities is provided by the wet weather program of East Bay Municipal Utility District’s (EBMUD) in northern California. The cost of that program in 2004 dollars is estimated to be about $600 million (Jerry Gilbert, J. Gilbert, Inc., personal communication, 2004); it is described as follows:7

In the 1980s, deteriorated community sewer pipes and improper storm drain connections allowed rainwater to enter local sewer systems during the heaviest storms, causing overflows at more than 175 locations. In 1986, EBMUD signed a joint powers agreement with Alameda, Albany, Berkeley, Emeryville, Kensington, Oakland, Piedmont, and portions of El Cerrito and Richmond to fix the problem. The communities have spent $200 million on sewer improvements and have a long-range program to complete improvements. EBMUD expanded facilities to provide more treatment capacity for high wet-weather flows. The communities’ sewer improvements will reduce the “peak” regional wastewater flows from 1.1 billion gallons per day to 775 million gallons per day (MGD). EBMUD’s treatment capacity will increase from 290 MGD to 775 MGD.

An approach similar to that taken in the EBMUD service area could be attempted in the Pittsburgh area with ALCOSAN as the central planning and management agency. The ultimate success of such an effort would depend in large part on relationships between ALCOSAN and its constituent communities.

ORGANIZATIONAL OPTIONS FOR IMPROVING WATER QUALITY MANAGEMENT IN SOUTHWESTERN PENNSYLVANIA

The cases discussed in the preceding section provide examples of organizational arrangements that other metropolitan areas have adopted to address their water resource and quality management problems. In many ways they are quite similar to the Pittsburgh region where there is a well-established special district providing sewer service to 83 communities, located primarily in a single urbanized county, and a designated MPO or regional planning agency exists. There are, however, several respects in which the Pittsburgh area lags some of the more established arrangements found elsewhere. First, comprehensive planning for stormwater management is relatively new in the region’s urban core, and there appears to be limited expertise to manage beyond capturing sewage overflows and transmitting them to a central wastewater treatment facility. Second, there is no comprehensive basinwide planning to address issues that transcend regional boundaries and legal jurisdictions. Finally, water quality and water resource planning at the metropolitan multicounty scale is poorly developed.

|

7 |

Available on-line at http://www.ebmud.com/wastewater/wet_weather/default.htm. |

Although comments by selected leaders of the Pittsburgh region who have been consulted by the committee do not constitute a scientifically representative poll of interests in the region, they reveal several important clues about the direction that should be taken to address the organization of water resource and water quality planning and management in the region. First, there does not now appear to be a consensus on what that direction ought to be. If the region is to take an initiative toward new organizational arrangements, serious further discussion around several specific alternatives will be necessary. A consensus must emerge from that discussion. Second, comments suggest that the Pittsburgh region shares many of the views held by other metropolitan areas that have addressed similar issues. They reflect the view that problems in the urban core are different from those in surrounding counties and multiple organizations will be needed to address such problems. The commentators seemed to suggest that water resource planning at the multicounty metropolitan level could be helpful, but it should be limited to an advisory role. They also seemed to agree that ALCOSAN is the appropriate agency for transmission and treatment of sanitary sewage to the extent that they believe current and planned expansions (see Chapter 5) are appropriate. Several commentators pointed to the positive role played by 3RWW in Allegheny County.

Options to address water resource and quality management needs at the basin scale, metropolitan/multicounty level, urban core and outlying urban centers, and rural areas are discussed in the following sections.

Basin Scale

Acid mine drainage, polluted agricultural runoff, mercury, and microbiological contamination, are among water quality problems identified in the Pennsylvania 305(b) report (PADEP, 2002a), discussed in Chapters 3 and 4, that may be exported out of individual watersheds into the region’s main stem rivers and across state boundaries. Monitoring, modeling, and the formulation of remedial policy have to be done at an appropriate scale that incorporates all significant sources impacting southwestern Pennsylvania and those downstream segments that may be affected by the Pittsburgh region. The most appropriate scale is likely to be at the river basin level and portions of tributary basins that cross state boundaries.

The most likely organizational options to investigate and resolve basinwide linkages are the Ohio River Valley Water Sanitation Commission (ORSANCO) and the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. Created in 1948, ORSANCO is an interstate commission representing eight states and the federal government to address water quality problems in the Ohio River and its tributaries. Pennsylvania is a member, along with Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, New York, Ohio, Virginia, and West Virginia. ORSANCO performs several water quality planning and monitoring functions, including establishing effluent standards for wastewater dischargers, conducting biological assessments, monitoring chemical and physical properties of streams, and executing special studies. Its staff has expertise in general administration, data management, water quality monitoring and modeling, pollutant reduction and NPS pollution programs, public information programs, wet weather projects and CSO abatement, and assessment of fish populations and their health. Because of ORSANCO’s long history in the field of water resource and quality management, its interstate structure, and its professional staff, it is ideally suited to address many of the basin-scale problems in the region, especially those that are interstate in nature.

In addition to their broad constitutional and statutory powers for regulating water quality, state government entities can also play a significant role in basinwide and regional water resource

planning and management. Pennsylvania is like 20 other states cited by the NRC Committee on Watershed Management (NRC, 1999) that have organized some of their management activities around watersheds—most importantly for acid mine drainage and rural nonpoint source pollutants. Formulation of the WRAS and commitments of funds discussed earlier in this chapter represent a significant advance toward confronting these problems. At a minimum, PADEP has to monitor and model (see Chapter 5) how much of the wet weather-related pathogen and heavy metal contamination problems in streams flowing through southwestern Pennsylvania are due to upstream sources. Corrective action should be taken to address these sources as well as those within the Pittsburgh region. The CWARP program discussed and recommended in Chapter 5 can be launched by the basinwide authorities that would establish watershed-based information collection and analysis programs to provide the foundation for work at the subbasin, urban area, or more rural (local) levels.

Multicounty/Metropolitan Scale

As noted previously, improved planning and technical assistance programs for water management at the metropolitan regional scale are needed. Large-scale transportation plans developed at that scale can have profound effects on land use and related water supply, stormwater, sanitary sewer services, and other aspects of water resources. Consideration of those effects should be incorporated in regional planning. Related needs at the metropolitan scale include the following:

-

examine alternatives to the existing, highly fragmented pattern of water resource services;

-

promote improved coordination among regional transportation, economic development, land use, and water resources; and

-

provide assistance to small urban centers and rural areas in matters of water supply and wastewater disposal.

At least two options are available to pursue that goal. One is to enhance capabilities of the existing metropolitan planning organization, SPC; the alternative is to create a new organization. The SPC currently derives its authority in large part from federal transportation incentives. If it is to do more than simply design transportation systems that follow existing development trends—and, in particular, if it is to take a leadership role in regional water planning—SPC’s regional planning will have to become more comprehensive. Several basic tasks could be conducted beneficially at that scale. Second, water resource considerations should be integrated with land use and transportation planning to determine resource availabilities, development needs, constraints, and environmental consequences of regional development. Plans at that scale should serve as guides for large-scale urban infrastructure investments that guide growth. Other tasks that have been successful in similar settings are technical assistance to local governments and subarea plans for watersheds within the region.

At least two problems potentially limit SPC as an effective leader in regional water planning and management. First, leadership of the organization is limited to elected officials. For the commission to be effective in bringing about cooperation among the region’s numerous local governments, it is important that those elected officials be at the table. However, some of the major water-related issues of concern to the region go beyond the sphere of local governments. Participation by other knowledgeable individuals, water management agencies, community and

nongovernmental organizations, academia, and other entities is necessary if a metropolitan planning organization is to better capture the benefits of the region’s leadership. Second, the commission is not proportionally representative of its 10-county population. Each of the 10 member counties is represented by five members of the governing board. Representation should reflect the fact that those counties with relatively high densities and a large number of intimately interrelated local governments have priorities that are quite different from those of the predominantly rural counties with relatively smaller and more dispersed populations.

The second option is to create a new special-purpose water quality planning and technical assistance organization at the multicounty level. Its principal advantages would be the creation of a strong voice for water quality improvements and development of a specialized staff for both technical matters and public outreach. Its disadvantages include the following: (1) creation of yet another regional organization that would have to raise revenue; (2) possible duplication of SPC’s regional database; and (3) a more difficult task of integrating water resource considerations with land use and transportation planning conducted by SPC.

In the judgment of the committee, the SPC is the region’s best choice for planning at the multicounty/metropolitan scale if its governance and participation can be modified to address the aforementioned limitations of participation and representation. One option for SPC to broaden participation is to take an active role in establishing and supporting a regional water forum discussed later in this chapter. SPC would also have to enhance staff capability in water planning and management.

Specific tasks that must to be accomplished by SPC (or a new special-purpose organization) include the following:

-

Prepare a regional framework plan for water resources that integrates water and land resource uses and capabilities with its transportation planning responsibilities:

-

identify the extent of need and management alternatives for on-site sewage treatment and disposal system (OSTDS) management in predominantly rural counties;

-

work with PADEP to identify the extent of need and management alternatives for municipal wastewater management in lesser urbanized counties;

-

work with the Ohio River Basin Regional Water Resources Committee created by PADEP under the 2002 WRPA to identify the extent of need and management alternatives for public water supplies in predominantly rural counties; and

-

identify critical water resource areas in need of protection or restoration.

-

-

Provide a continuing regional forum for discussion of issues and management options for addressing common problems shared by at least a subset of local governments.

-

Provide advice to local governments as appropriate.

Urban Core and Outlying Urban Centers

In the urban core, including much of Allegheny County and portions of Washington, Westmoreland, Butler, and Beaver Counties, the dominant water quality management problems are combined sewer overflows and sanitary sewer overflows (SSOs) resulting from wet weather conditions. These specific problems, however, are inextricably linked to the more general problem

of stormwater management. Actions taken to manage stormwater flows in one location may have significant effects over a much larger portion of the network; elimination of some CSOs and SSOs will have spillover effects on separate stormwater conveyances. To some extent, these problems may also exist in smaller, detached urban centers in the region.

Continued fragmentation of the management of the sewer collection-conveyance-treatment system (i.e., maintaining the status quo) is not a satisfactory situation. Not only is it inefficient; it also impedes solutions. A system in which more than 80 municipalities discharge unregulated quantities of stormwater runoff and sanitary sewage into a centralized conveyance-treatment system over which the treatment management agency (ALCOSAN) has insufficient physical and fiscal control is a recipe for maintaining and possibly worsening current water quality conditions. If contributing municipalities persist in independent operations of their collection systems, some form of performance standards and incentives to comply with those standards should be established. The cost to small communities that choose to “go it alone” in satisfying such standards could be prohibitive.

A plan that integrates separate sanitary sewer systems, separate stormwater systems, and combined sewers should be prepared for the region’s urban core. Its geographic coverage should include, at a minimum, all of the watersheds that contribute urban stormwater runoff and/or sanitary sewage to the ALCOSAN system, excluding those watersheds upstream on the Allegheny, Monongahela, and Youghiogheny Rivers. Exact delineation of boundaries for such a plan will have to be made pending a more detailed examination of the area, but a first approximation is provided in Figure 5-2.

A recent example of integrated management of separate sanitary sewers, separate storm sewers, and combined sewers is the case of nearby Morgantown, West Virginia, described in Box 6-2. Although Morgantown is a much smaller community than Pittsburgh, it experiences similar water quality problems.

Combined sewer overflows are inherently linked to collection systems for sanitary sewage and stormwater runoff. Although ultimate decisions on governance of these problems may result in a clear delineation of responsibilities, those decisions should be made in light of consequences for all aspects of stormwater and sanitary sewage collection, treatment, and disposal.

Several alternatives should be considered for planning and managing sanitary sewage and stormwater in the region’s urban core; principal among them are the following:

-

Option A: General-purpose metropolitan government—specifically merger of the City of Pittsburgh and surrounding municipalities with Allegheny County

-

Option B: Creation of a countywide sewage collection organization, with or without authority over stormwater management, either by dedication of sewer systems to Allegheny County or through an administrative arrangement with Allegheny County using authority under Pennsylvania Acts 67 and 68

-

Option C: Creation of one or more special districts to manage sewer collection with or without authority over stormwater management

-

Option D: Expansion of the role of ALCOSAN to include sewer collection systems, with or without authority over stormwater management

-

Option E: Continuation of the decentralized system but with performance standards and voluntary participation in a regional maintenance organization (RMO) provided on a fee-for-service. ALCOSAN would be encouraged to establish the RMO.

|

BOX 6-2 Morgantown, West Virginia, located approximately 90 miles south of Pittsburgh, has a permanent population of 25,000 and an additional student population of 25,000 at West Virginia University. The municipality owns and operates the Morgantown Utility Board (MUB) that serves approximately 21,000 potable water customers and 14,000 sanitary sewer customers. Beginning in August 2002, MUB inaugurated a stormwater utility serving 10,000 customers. MUB is governed by a Board of Directors appointed by the City Council. Until 2002, stormwater services in Morgantown were provided by the city’s street department. Spurred in part by the need to obtain a stormwater discharge permit under Phase II of regulations promulgated by EPA, the city moved responsibility to MUB. Factors influencing that move included MUB’s greater expertise with state and federal water quality permits and an acknowledgement that the time had come to undertake costly rehabilitation of its stormwater system. Also, two densely populated and growing neighborhoods were experiencing damage from floodwater, much of which originated beyond the city’s planning and zoning jurisdiction. MUB’s acceptance of this new responsibility acknowledged the inherent interconnectedness of its separate sanitary sewers, separate stormwater management system, and combined sewer system, all of which were subject to state and federal permits. A key issue in the formation of the stormwater utility was establishing the service area. After much discussion, the area was defined as the watershed from which overland flow is delivered to a receiving stream within the city limits. Minor adjustments to that delineation were necessary to account for a few other practical considerations. Because MUB’s stormwater jurisdiction extended beyond the city’s jurisdiction and West Virginia law was silent on the issue of municipal stormwater management outside corporate boundaries, state enabling legislation was necessary to address the issue of authority. The legislature passed the enabling legislation through a series of amendments to the West Virginia Code. After several months of interaction with affected stakeholders, the City Council passed the newly enabled municipal ordinances creating the stormwater utility. A flat rate of $3.63 per month was adopted for single-family residences. For multifamily residences and nonresidential properties, the fee was set at $0.00145 per month per square foot of measured impervious surface. These fees are expected to generate about $750,000 annually. SOURCE: Timothy L. Ball, MUB, personal communication, 2004. |

Whatever option is chosen, management entities would have to meet performance standards to minimize CSOs and SSOs. Performance standards should, at a minimum, conform to EPA’s CSO Control Policy (EPA, 1994; see Chapter 5 for further information), the joint memorandum “Enforcement Efforts Addressing Sanitary Sewer Overflows” (Harman and Perciasepe, 1995) from EPA’s Office of Enforcement and Compliance Assurance and Office of Water, and “Chapter X: Setting Priorities for Addressing Discharges from Separate Sanitary Sewers” (EPA, 1996) of the National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) Enforcement Management System. EPA’s Region IV Capacity, Management, Operation and Maintenance (CMOM) policy could serve as a model (see Herman, 2000). Discussion of options A through E as they pertain to southwestern Pennsylvania is provided below.

Option A

Discussion of consolidation of the City of Pittsburgh and Allegheny County has been raised recently as a possibility by the Allegheny Conference on Community Development in the context of the region’s current fiscal woes (McNulty, 2003; see also Chapter 2). Both the mayor and the county executive at that time called for a study of the proposition. The issue was raised more recently at a

meeting of the League of a Women Voters in February 2004 (Cohan, 2004) by Mayor Tom Murphy and county Chief Executive Dan Onorato who commented that the issue was definitely on their agendas. A merger of the City of Pittsburgh and Allegheny County would cover a sizable portion of the geographical area of the region’s high density urban core. Given the broad array powers delegated to municipal government, the merged government would have a wide array of authority to implement CWARP in that area. However, a merger of city and county government would achieve less than its full potential if the City of Pittsburgh is the only municipality involved. If surrounding municipalities that contribute sanitary sewage, stormwater, or combined sewage to the urban core continue to operate independent collection systems, the need for an additional mechanism for cooperation will remain. With full recognition that the decision will not and should not be made solely on water-related issues and will be politically difficult, the committee recommends the merger of city and county governments as an efficient and effective option for planning and management of water quality. With such a merger, a large portion of the area affected by CSOs, SSOs, and urban stormwater runoff could be brought under a single management entity that can integrate water management with land use. Under this option, ALCOSAN would continue to own and operate interceptors and treatment facilities.

If Option A is chosen, management of water resources in contiguous urban areas outside Allegheny County that contribute flows to Allegheny County would not be addressed. Management in those areas could be either independent or by administrative arrangements with Allegheny County under one of several Pennsylvania statutes enabling intergovernmental cooperation. Options D could be adopted for contiguous urban areas; Options C or E are possibilities for outlying urban areas that are detached from the urban core.

Option B

Option B for managing sanitary sewage and stormwater in the urban core has at least three components, namely, (1) a countywide sewer organization; (2) continuation and possible expansion of 3RWW programs; and (3) continuation of ALCOSAN as the operator of major interceptor sewers and centralized wastewater treatment.

Countywide sewer system management could be established either by B(1) dedication of local sewer systems to the county or by B(2) intergovernmental contracts through an Intergovernmental Cooperative Planning and Implementation Agreement as authorized under Pennsylvania Acts 67 and 68. Either the City of Pittsburgh or Allegheny County could be the operating entity. If Allegheny County took on this responsibility, it would have to establish an administrative unit capable of handling these duties. However, a decision would still have to be made about who would be responsible for stormwater runoff.

If municipal governments chose to surrender management of their sewer collection systems to a countywide entity under either Option B(1) or B(2), that entity would function as an operating agency for all sewer systems services and include the following responsibilities:

-

construction, operation, and maintenance of all sewer systems in the county;

-

construction, operation, and maintenance of decentralized stormwater treatment required to satisfy the long-term control plan for CSOs; and

-

financing through tax revenues or a system of charges to individual residential, commercial, industrial, and governmental contributors to the sewer network.

The second component of Option B includes the 3RWW, and the committee recommends that it be continued or expanded. Its functions are and should include the following:

-

conduct a public education program and provide technical assistance to local governments for stormwater and CSO management;

-

provide an educational program to local governments for identifying and correcting illicit connections to sewer system; and

-

monitor, analyze, and report periodically on the status of stormwater and CSO management in Allegheny county.

ALCOSAN’s existing role would continue under Option B, and it would (1) provide conveyance of combined sewers to the treatment plant; (2) provide appropriate treatment for sanitary and storm sewage conveyed to the central treatment plant; and (3) establish and collect fees for those services.

Option C

The third option is to form one or more sewer utilities where groupings of municipalities would be determined on geographic, political, and economic criteria. As in Option B, a decision would have to be made about who would be responsible for stormwater runoff. Option C would be very similar to Option B except that it would be organized under different authority. It would be similar to ALCOSAN and financed through a set of user fees. If its responsibilities were limited to sanitary sewer and CSOs, fees would be assessed on wastewater discharges. If its responsibilities included broader responsibilities for stormwater management, it could also include stormwater utility fees.

It is important to note that the option of special-purpose districts is not limited to a single district such as ALCOSAN. Metropolitan areas with a very large special district serving the central core of the urban area may have smaller districts that offer similar services to outlying areas. The U.S. Census Bureau lists all individual special districts with major financial activity (MFA), defined as those units with either revenues or expenditures in excess of $10 million or debt in excess of $20 million. In the Chicago metropolitan area, for example, where the Metropolitan Water Reclamation District had expenditures of about $650 million in 1997, there are two MFA special districts that deliver sewerage services in Kane and Lake Counties, each with less than $20 million of expenditures in 1997. In the St. Louis metropolitan area, an MFA special district delivers sewer service in St. Charles County. It spent about $27 million in 1997. In Boston, the South Essex Sewerage District, serving portions of the North Shore, spent $87 million in 1997. Similar subregional arrangements could be identified within the region beyond the boundaries of ALCOSAN.

Option D

Instead of creating any new organization to manage sewage collection systems and possibly stormwater management as well, ALCOSAN’s existing mandate could be expanded to include collection systems and possibly stormwater. Municipalities could choose to either dedicate their

systems to ALCOSAN or retain ownership.

If municipalities chose to retain ownership, ALCOSAN would be charged with the following tasks:

-

establishment and enforcement of performance standards for municipal stormwater discharges throughout the county;

-

construction, operation, and maintenance of the decentralized stormwater treatment facility required to satisfy a long-term control plan;

-

establishment of a rate structure for assessment of management fees;

-

construction, operation, and maintenance of drainage systems for member communities; and

-

continued contribution to the operation of 3RWW.

If local governments chose to surrender their general stormwater management responsibilities to ALCOSAN, those responsibilities would be added to the preceding list and ALCOSAN should be given authority to charge stormwater utility fees for those services.

As in the case of Option B, the committee recommends continuation or expansion of 3RWW.

Option E

The fifth option is for municipalities to retain local ownership of sewer collection and stormwater facilities. Operators of systems would be required to demonstrate their capacity to operate and maintain those systems in accordance with performance criteria established by PADEP and EPA or to enter into service contracts with a qualified provider. ALCOSAN would be encouraged to develop a sewer services division that would provide requisite operation and maintenance functions on a fee-for-service basis. As in Options A, B, and D the continuation or expansion of 3RWW is recommended.

Summary of Options A-E

Discussion of Option A is already in progress. Given the length of time required to make a decision on a merger and uncertainty about the outcome of that decision, it is recommended that Allegheny County take the lead in the near future to form a task force to consider Options B, C, D, and E. Although the committee is of the opinion that Options B-E are all viable, it prefers Option B. A countywide sewer organization created under Option B could develop an Act 537 plan (see Chapter 5 for further information) that includes all local governments in Allegheny County and portions of neighboring counties that choose to participate. Such a countywide organization would also have the option of contracting with ALCOSAN for selected services as suggested under Option E. Thus, Option B offers advantages of economies of scale in planning, operation, and maintenance; facilitates a systems approach to management; can be managed through existing institutions; and keeps governance of the program close to politically accountable public officials. Specific project planning and development as well as operational coordination would be conducted under the appropriate option identified above. Lastly, the advantages and disadvantages of these five options for planning and managing sanitary sewage and stormwater in the region’s urban core are summarized in Box 6-3.

|

BOX 6-3 Option A: General-purpose metropolitan government Advantages:

Disadvantages:

Option B: Countywide sewage collection organization using authority under Pennsylvania Acts 67 and 68 Advantages:

Disadvantages:

Option C: Creation of one or more special districts to manage sewer collection with or without authority over stormwater management Advantages:

Disadvantages:

Option D: Expansion of the role of ALCOSAN to include sewer collection systems, with or without authority over stormwater management Advantages:

Disadvantages:

Option E: Continuation of the decentralized system with performance standards Advantages:

Disadvantages:

|

Rural Areas

As stated previously, the primary rural area problems identified by the committee are inadequate on-site wastewater disposal and water supplies, and the actions recommended in Chapter 5 to address these deficiencies (e.g., register all individual and cluster OSTDSs within each county in southwestern Pennsylvania) should be undertaken cooperatively by several agencies. At the state level, the WRAS program should be expanded to include assessment of effects of inadequate wastewater disposal on water quality. In doing so, PADEP should work closely with local governments having legal authority over such systems. Although the legal authority to control on-site water supply and wastewater disposal rests with municipalities and counties, it is unlikely that individual units of local government will have sufficient resources to support an effective management capability for these functions. The SPC could and should take strong leadership in bringing local governments together to address these issues. In addition to PADEP, SPC should request assistance from EPA and nongovernmental organizations having prior experience with programs of this kind. The Allegheny County experience in these activities should provide a sound foundation for other counties in the region.

Consistent with Chapter 5, the committee recommends that initial funding from a regional user surcharge be provided to initiate such county activities that eventually would be self-sustaining.

Regional Water Forum

Regardless of which management option is chosen at the metropolitan regional scale, there is a need for a continuing forum on water resources and related issues in the region and, more specifically, for general oversight of the CWARP, the progress being made, and the need for further actions toward achievement of clean water. As discussed earlier in this chapter, southwestern Pennsylvania is served by a diversity of water planning and management institutions, both large and small in geographic scope and both public and private in legal structure. These existing entities appear to be reasonably cooperative on issues of common regional interest. An excellent recent success in intersectoral collaboration was the Western Division of the Pennsylvania Economy League’s WSIP project and its 2002 report discussed earlier (see also Appendix B).

The WSIP, however, was both ad hoc and focused on a single issue. The WSIP Steering Committee went out of existence with the publication of its report in 2002, although leaders in the effort continue to press for action as evidenced by this study and report. However, this NRC study is also a singular event to consider and provide advice on options. Water resource planning and management for southwestern Pennsylvania should be continuous and multiple-purpose in scope, including at least the following areas of concern:

-

water quality—CSOs, SSOs, stormwater, failing OSTDSs, acid mine drainage (AMD), other;

-

water supply—household, institutional, industrial, other;

-

aquatic and riparian habitat restoration, including fisheries;

-

recreation—urban riverfront, water contact; boating, fishing, other;

-

flood hazard and drought mitigation; and

-

“sense of place” for the Pittsburgh region, (e.g., preservation of historic cultural landscapes and structures relating to the Three Rivers watershed).

An overlying water resource management “umbrella” is needed to incorporate as many areas of water management concern and stakeholders as possible. The “umbrella” would not be an operating agency that could assume all of these functions. Rather, it would be a regional water forum that would offer open access to interested stakeholders (or representatives of different classes of stakeholders) and be directed to the full spectrum of interconnected water resource issues such as those listed above.

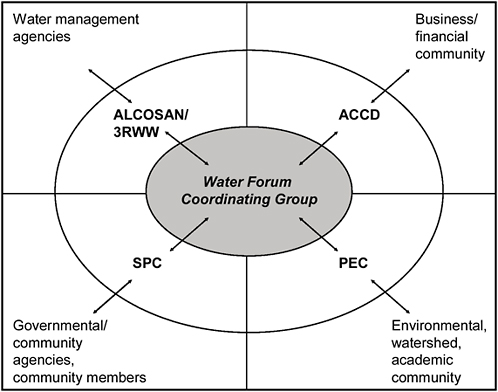

The 2002 WSIP report proposed a water management framework involving three functional areas, each under the leadership of an existing institution, to be coordinated by a hypothetical Watershed Alliance for the Three Rivers Region (WATRR). As stated previously, the three-pronged and interrelated functional elements of the proposed framework would include technology and education, regional goal and priority setting, and advocacy.