Executive Summary

The national smallpoxvaccination program announced on December 13, 2002, was the result of an extraordinary policy decision: to vaccinate people against a disease that does not exist with a vaccine that poses some well-known risks. The rationale for such a decision can be considered only against the backdrop of the terrorist and bioterrorist attacks of 2001.

The vaccination program is a case study at the intersection of public health and national security, two fields brought together by the threat of bioterrorism. The vaccination campaign has involved government entities (such as homeland security) and required considerations (such as classified information) generally not encountered in typical public health programs.

Bioterorrist attacks epitomize “low-likelihood, high-consequence” events.1 Preparing for such events is challenging—efforts to prepare for an event that may never occur are likely to come under criticism if the threat never materializes. Also, such events are accompanied by uncertainty, including an unclear ratio of risk to benefit. For this reason, implementing a program of preparedness for bioterrorism and similar types of events requires careful consideration of information and communication needs. In the smallpox vaccination program, the uncertainty surrounding the threat created a great need for information among key constituencies.

Before the beginning of the smallpox vaccination program, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) asked the Institute of Medicine (IOM) to convene an expert committee to advise it on the implementation of a pre-event smallpox vaccination program. The committee was charged with providing “advice to the CDC and the program investigators on selected aspects of the smallpox program implementation and evaluation,” including the informed consent process for recipients of smallpox vaccine; professional education and training materials; communication plans developed by CDC for public health and medical professionals and the public; state smallpox vaccination implementation plans; CDC guidelines and instruments to identify potential vaccine recipients at high risk of vaccine adverse events and complications; CDC measures to ensure the early recognition, evaluation, and appropriate treatment of adverse events and complications of smallpox vaccination; CDC plans for collecting and analyzing data on vaccine immunogenicity, adverse events, complications, and vaccine coverage; and the achievement of overall goals of the smallpox vaccination program, such as vaccine coverage rate, equity of access, and adverse reaction rates. The IOM agreed to provide advice through a series of reports responding to CDC’s original charge and to new requests that would arise in the course of program implementation.

In a series of six brief timely reports released over 19 months, the committee presented its findings and offered recommendations to help guide the program and, later, its integration into the broader public health preparedness effort. In its first four reports, the committee’s recommendations focused on staff training and education, the informed consent and contraindications screening processes, the collection of data, follow-up and conduct of research related to vaccine adverse events, public communication, and the need for vaccine injury compensation. The committee also recommended evaluating all program components (including issues related to cost), defining smallpox preparedness to help establish a baseline or standard against which preparedness efforts could be measured, and using scenarios, including multithreat scenarios, to sharpen national and local plans to respond to smallpox and other threats. In its fifth and sixth reports, the committee responded to CDC’s request to comment on its draft indicators of smallpox preparedness (in the context of a larger set of public health preparedness indicators), on the value of using scenarios, and on the state of the science (across other disciplines, such as disaster response) on the conduct of exercises as a strategy for evaluating and testing preparedness. The six individual letter reports have been gathered into a larger archival work that also responds more substantively on the last item in the charge, the achievement of overall goals of the smallpox vaccination program.

This final report consists of four newly written chapters and seven

appendixes that contain the committee’s body of prior work. The first appendix contains a summary of the recommendations in the committee’s six previous reports. The remaining appendixes contain the complete text of the committee’s first six reports, released from January 2003 to July 2004 in response to CDC’s requests for specific and timely advice, and they reflect in part information gathered at the committee’s public meetings held from December 2002 to March 2004.

The report’s first chapter, “Smallpox and Smallpox Control in the Historical Context,” provides a brief summary of the history of smallpox and its eradication. The historical narrative explains the near-mythic status of smallpox among other dangerous diseases, but it also tells the hopeful story of a disease that was vanquished thanks to an effective vaccine and the coordinated and capable efforts of public health and health care workers around the world.

The second chapter, “Policy Context of Smallpox Preparedness,” outlines policies that predated the 2002 smallpox vaccination policy and describes key events and people that contributed to the decision to vaccinate selected groups in advance of a potential smallpox virus release. The chapter is intended to provide some background information about the complex circumstances (such as the high level of public, congressional, and media interest) surrounding the federal government’s decision to revive smallpox vaccination. The committee believes that its summary of the program’s policy context is consistent with its charge because it highlights early factors that the committee asserts influenced the implementation and outcomes of the vaccination program. Specifically, CDC’s difficulties in communicating about the smallpox vaccination policy and program and in securing the participation of public health and medical professionals (the third item in the committee’s charge) may be traced to the way the policy and its rationale were communicated to key constituencies.

In the report’s third chapter, “The Implementation of the Smallpox Vaccination Program,” the committee provides a loosely chronological account of the program’s implementation structured around major events, from the president’s program announcement in December 2002 to the enactment of a compensation plan for injuries resulting from smallpox vaccination in April 2003 and the June 2003 Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommendation to bring pre-event smallpox vaccination to a close. The committee also explores congressional interest in the program and the relationship between the civilian and military smallpox vaccination programs. The chapter includes a discussion of vaccination program challenges. The committee found that the implementation of the program was compromised by operational factors related to broader, strategic issues (examined in Chapter 4). For example, some of the program’s challenges were due to its extraordinarily rapid implementation; there was

little time to identify and resolve potential difficulties (such as the lack of a compensation plan) or to plan carefully for crucial program components, including materials for prospective vaccinees and the data system. Although rapid implementation would be justified in a crisis, the public and program participants were repeatedly assured that there was no evidence of imminent attack with smallpox virus. Chapter 3 also includes a discussion of favorable outcomes and concludes with a detailed chronology, from events that paved the way for the program through the time of this writing. In this chapter, the committee cites mass media references that document the perspective of key constituencies and their perceptions of the program and the federal government’s role. Although media sources are limited in some ways, they provide important insight into the implementation of the program, and the committee has found them concordant with information gathered during the committee’s public meetings.

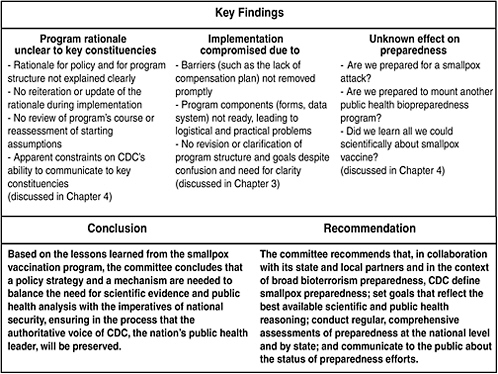

The report’s fourth and final chapter, “Lessons Learned from the Smallpox Vaccination Program,” constitutes the core of the report, and in that chapter the committee discusses two additional sets of findings from its review of the program and provides a conclusion and a recommendation based on the findings (see Figure ES-1). Trust is a unifying theme among the committee’s findings. The committee asserts that a relationship of trust between CDC and the public health and health care communities is a critical requirement in the implementation of biopreparedness programs.

The committee recognized that CDC requested IOM’s guidance on the implementation of the program, not on the smallpox vaccination policy itself. Therefore, in its deliberations the committee made every effort to separate the program from the policy-making that preceded it. In Chapter 4, the committee continues its work within the boundaries of the charge by not commenting on the substance of the policy itself. However, the committee’s interpretation of its charge is broadened somewhat, allowing it to examine the way the policy and its rationale were communicated and the effects that appeared to have had on the implementation of the program and on the achievement of overall goals of the program (as stated in the last item of the charge).

The smallpox vaccination program involved the implementation of a public health strategy that required the buy-in and participation of numerous public health and health care administrators and personnel. It is a well-documented principle of health promotion planning that the commitment and attitudes of staff who will implement a program are critical to its success, and that they are shaped in the process of communication and information-sharing (Green and Kreuter, 1991). Also, public health practitioners have long known that the activities of community health improvement require “buy-in from those who control what is to be changed” (Nolan, 2004). Smallpox vaccination has been implemented as a public

FIGURE ES-1 Key findings, conclusion, and recommendation.

health component of a national security program, so the principles outlined above apply. It was important to ensure that the people who would implement the program understood and supported the rationale for the program. However, the committee found that the key constituencies expected to play vital roles in the implementation of the vaccination program did not receive sufficient information about the reasoning that led to the program and remained skeptical of the need for pre-event vaccination.

The vaccination policy set expectations for numbers of vaccinees to be reached in three phases beginning with rapid implementation of the first phase, but no explanation for that overall strategy was offered to those who would implement it. For example, when the smallpox vaccination policy ultimately developed by top officials of the executive branch (of which CDC is a part) diverged from the recommendations of ACIP, the panel that advises the government on immunization policy, only vague explanation was given. Although it is understandable that the policy for the public health component of a national security program would be shaped by information from both fields, the national security assessment informing it was not available (except for the caveat that there was no information to suggest that an attack was imminent), and the public health reasoning

behind the smallpox vaccination policy and program was never fully explained. Skepticism among key constituencies was followed by a lack of buy-in. Despite their expressed willingness to strengthen preparedness for bioterrorism in general, and their desire to serve their communities, many public health and health care workers were ultimately unwilling to accept the well-known risks of smallpox vaccine in the context of limited information about the risk of smallpox. The lack of buy-in led to poor participation in the vaccination program.

In addition to the fact that the rationale for the program and its structure was not explained, communication with key constituencies created confusion and concern. The typically open and transparent communication from CDC—the nation’s public health leader that generally provides guidance for science-based decision-making—seemed constrained by unknown external influences. Furthermore, as the program was experiencing difficulties and appeared to fall short of initial expectations, goals were not clarified or revised in any substantial way. For example, if it was important to vaccinate specific numbers rapidly, what was the effect of the low vaccinee numbers on readiness for a release of smallpox virus? This question went unanswered, as did the larger questions about the definition and requirements of smallpox preparedness.

Based on the lessons learned from the smallpox vaccination program, the committee concludes that a policy strategy and a mechanism are needed to balance the need for scientific evidence and public health analysis with the imperatives of national security, ensuring in the process that the authoritative voice of CDC, the nation’s public health leader, will be preserved.

Finally, the committee found that the program’s outcomes (for example, the status of smallpox preparedness in each jurisdiction and nationally) are unknown because there has been no systematic assessment of smallpox preparedness, no review of administrative lessons learned, and no accounting of what has been done with the opportunities for scientific research. At the time of this writing, the status of efforts to develop measures and indicators for smallpox (and bioterrorism) preparedness is unknown.

The committee recommends that, in collaboration with its state and local partners and in the context of broad bioterrorism preparedness, CDC define smallpox preparedness; set goals that reflect the best available scientific and public health reasoning; conduct regular, comprehensive assessments of preparedness at the national level and by state; and communicate to the public about the status of preparedness efforts.

The trust of the general public in government’s ability to protect the public’s health also is a critical requirement for responding to bioterrorism. Conducting and disseminating assessments of national and state preparedness will inform and reassure Americans about the public health system’s ability to protect their health and will help jurisdictions continuously improve and learn from the process of preparing for public health emergencies, including a possible smallpox virus release.

It is an unfortunate reality that bioterrorism continues to be a threat. Therefore, future programs to prepare for this type of low-likelihood, high-consequence event will be needed, and the lessons learned from the smallpox vaccination program may help to ensure successful implementation.

REFERENCES

Green L, Kreuter M. 1991. Health Promotion Planning: An Educational and Environmental Approach. Mountain View, California: Mayfield Publishing Company.

Nolan P. 2004. The choice of the public in public health policy and planning: the role of public judgment. Journal of Public Health Policy 25(2):209-210.