3

Preventing Cancer

“Georgia will have the lowest incidence, prevalence, and mortality rates for cancer in the nation.”

Strategic Plan for the Georgia Cancer Coalition, 2001

“Failure to implement proven methods of cancer prevention leads to avoidable disease and death. A 19 percent decline in the rate at which new cancer cases occur and a 29 percent decline in the rate of cancer deaths could potentially be achieved by 2015 if efforts to help people change their behaviors that put them at risk were stepped up and if behavioral change were sustained.”

Fulfilling the Potential of Cancer Prevention and Early Detection

Institute of Medicine, 2003

The objective of cancer prevention is to avoid the development of cancer through the use of interventions that eliminate or reduce exposures to the causes of cancer (e.g., tobacco and other carcinogens, obesity). In health care’s arsenal of weapons to fight cancer, prevention holds tremendous potential (IOM, 2003). The Georgia Cancer Coalition (GCC) could harness much of the untapped potential of cancer prevention by working to close the gap between what is known and what is practiced in the common, everyday routines of physicians’ offices. Among the first steps GCC might take to prevent unnecessary cancer morbidity and mortality are encouraging the use of evidence-based, effective means to help smokers quit smoking, as well as seeking to ensure that effective cancer screening procedures are used as recommended (see Chapter 4, Detecting Cancer Early) (IOM, 2003).

The Institute of Medicine (IOM) Committee on Assessing Improve-

|

BOX 3-1 Smoking Rates and Interventions

Trend in Obesity

Cancer Incidence Rates

|

ments in Cancer Care in Georgia recommends that Georgia adopt 10 quality indicators related to cancer prevention (Box 3-1). Four recommended measures are related to smoking rates and smoking cessation interventions. Smoking is the cause of 30 percent of all cancers, and almost one in four adults and high school students in Georgia smoke. The fifth recommended measure tracks obesity. Obesity is another major risk factor for cancer, but evidence-based solutions for reducing obesity are more elusive than those available for reducing smoking. The final five measures are measures of various cancer incidence rates. Cancer incidence rates are the ultimate indicators of the success of prevention efforts. With sustained meaningful improvement in cancer prevention, Georgia should eventually experience declining cancer incidence rates.

The 10 quality measures pertaining to cancer prevention recommended for Georgia are identified in this chapter. In addition, the rationale for the IOM committee’s selection of these measures is provided. For each measure, there is a section providing a brief explanation of the evidence underlying the measure (the “consensus on care”) and a description of what is known about the gap between the evidence and current practice (“knowledge vs. practice”). Also provided near the end of this chapter is a brief section on the potential data sources for the 10 recommended measures related to cancer prevention. The chapter concludes with one-page summaries of each

quality measure, including specifications for calculating the recommended measures. Chapter 4 (Detecting Cancer Early), Chapter 5 (Diagnosing Cancer), and Chapter 6 (Treating Cancer) are similarly organized.

RECOMMENDED MEASURES FOR TRACKING THE QUALITY OF CANCER PREVENTION

Smoking Rates and Interventions

The IOM committee recommends four measures to monitor smoking interventions in Georgia. Two of them are measures for routine surveillance of adult and adolescent smoking rates:

-

Measure 3-1—Adult smoking rate—the proportion of adults who smoke cigarettes.

-

Measure 3-2—Adolescent smoking rate—the proportion of adolescents who smoke cigarettes.

The other two are measures to monitor delivery of recommended smoking cessation interventions:

-

Measure 3-3—Smokers who receive advice to quit—the proportion of adult smokers who were advised to quit smoking during a visit with a doctor, nurse, or other health professional.

-

Measure 3-4—Smokers who are recommended pharmacotherapy to assist in quitting smoking—the proportion of adult smokers whose doctor, nurse, or other health professional recommended or discussed medication to assist quitting smoking.

Cigarette smoking accounts for at least 30 percent of cancer-related deaths and a staggering 87 percent of lung cancer deaths (ACS, 2004). Smokers are 20 times more likely than never-smokers to develop lung cancer (Alberg and Samet, 2003). Smoking is also a major cause of cancer of the larynx, oral cavity, throat, and esophagus and is a contributing cause in the development of cancers of the bladder, pancreas, liver, uterine cervix, kidney, stomach, colon and rectum, and some leukemias. An individual who quits smoking or refrains from starting smoking will experience substantial and immediate health benefits (U.S. DHHS, 2004).

If tobacco use does not begin in childhood or adolescence, it is unlikely to start in adulthood. Most adult smokers have their first cigarette before age 18, and more than half are daily smokers by age 18 (U.S. DHHS, 1994). Smokers who quit before age 50 have one-half the risk of dying in the next 15 years compared with continuing smokers. The benefit is even greater for

younger smokers who quit (Peto et al., 2000). The U.S. Surgeon General’s office has estimated that after 10 years abstinence, the risk of lung cancer is 30 to 50 percent of the risk for continuing smokers (U.S. DHHS, 1990).

Consensus on Care

There is a wealth of evidence documenting how health providers can influence adult smokers to quit and an extensive body of clinical guidelines promoting the use of these interventions (U.S. DHHS, 2004). More than 100 randomized controlled clinical trials have shown modest but statistically significant reductions in tobacco use for adult smokers who receive physician counseling (Fiore et al., 2000; USPSTF, 2002). The likelihood of quitting smoking increases with the intensity of counseling (Fiore et al., 2000).

In its most recent review of the evidence on the efficacy of smoking interventions, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) concluded that, compared with no intervention, smoking-cessation interventions that include screening, behavioral counseling (as brief as 3 minutes), and pharmacotherapy delivered in primary care settings, are effective in helping adult smokers quit smoking and remain smoking-free after 1 year (USPSTF, 2002). Numerous pharmacotherapies approved by the Food and Drug Administration—including bupropion, nicotine gum, nicotine transdermal patches, inhalers, and nasal sprays—have been shown to be safe and effective for treating tobacco dependence. Success in abstaining from smoking among people who use these pharmacotherapies ranges from 18 to 31 percent, as compared with 10 to 17 percent among people who do not use them (Fiore et al., 2000).

In addition to the literature on clinical interventions, there is a substantial literature on community-based strategies for reducing exposure to environmental tobacco smoke, encouraging tobacco-use cessation, and discouraging the onset of tobacco use in children and adolescents (CDC, 2000).1 Increasing the cost of tobacco and tobacco control programs that include mass media campaigns are among the strategies that have been shown to reduce the initiation of tobacco use among children and adolescents (Hopkins et al., 2001).

Unfortunately, little is known about the effectiveness of physician

|

1 |

Given this report’s focus on clinical indicators of quality care, it was beyond the scope of this study to assess potential indicators of community-based approaches to cancer prevention. GCC should consult the work of the U.S. Community Preventive Services Task Force for further information and evidence (see, for example, http://www.thecommunityguide.org/cancer/default.htm). |

TABLE 3-1 Cigarette Smoking by Adults and Adolescents in Georgia

|

Population group |

Estimated smoking rate (%) |

||

|

Female |

Male |

Both sexes |

|

|

Adults, ages 18 and older (2002) |

20.1 |

26.6 |

23.2 |

|

Adolescents |

|||

|

—Grades 9-12 (2001) |

19.9 |

27.4 |

23.7 |

|

—Grades 6-8 (2001) |

7.1 |

10.5 |

8.9 |

|

SOURCE: Martin et al., 2004; Kanny et al., 2002. |

|||

counseling of children and adolescents in preventing smoking initiation or promoting cessation (USPSTF, 2002).

Knowledge vs. Practice

Smoking is common in Georgia, as it is elsewhere in the United States. About 23 percent of the state’s adults and high school students smoke cigarettes (Table 3-1). More than 10 percent of Georgia’s sixth- to eighth-grade boys say they smoke cigarettes.

Despite the persuasive body of evidence supporting interventions to help smokers quit, many health providers do not follow the well-established guidelines for helping their smoking patients quit the habit. Nationwide, for example, in 2000 only 62 percent of adult smokers reported that their doctor had advised them to quit during a routine office visit in the previous year (AHRQ, 2003).

Smoking prevention and cessation has been recognized by GCC as an essential part of the fight against cancer. Approximately 37 percent of GCC’s funds since 2001 have been invested in tobacco use prevention (GCC, 2003). Tracking smoking rates and the delivery of smoking cessation interventions will help GCC monitor its impact on the leading preventable cause of cancer.

Trend in Obesity

The IOM committee recommends that GCC regularly monitor rates of adult obesity in the state:

-

Measure 3-5—Adult obesity rate—the proportion of adults who are obese.

Obesity is commonly defined using the formula based on weight and height known as the body mass index (BMI). Persons with a BMI of 30 or higher are considered obese. BMI is calculated as weight (in pounds) divided by height (in inches squared) multiplied by 703.2 The chief causes of obesity are a sedentary life style and a high-calorie diet (Friedenreich, 2001; Kritchevsky, 2003).

Reporting adult obesity trends will be fundamental to tracking Georgians’ risk for developing cancer. There is evidence that weight control may play an especially important role in the metabolic conditions amenable to carcinogenesis (Friedenreich, 2001). Numerous studies of cancer incidence show a relationship between increasing weight gain and the onset of cancer (IOM, 2003; Key et al., 2004). Recent estimates indicate that about 10 percent of breast and colorectal cancers can be attributed to overweight and obesity, and 25 to 40 percent of kidney, esophageal (adenocarcinoma), and endometrial cancers (Vainio and Bianchini, 2002).

Weight loss of only 5 to 10 percent of total weight provides health benefits such as improved lipid levels and blood pressure rate. However, it is not known if weight reduction in adult life meaningfully reduces one’s risk of developing cancer.

Consensus on Care

Despite growing scientific evidence on the role of obesity in the epidemiology of cancer, there is a little evidence on the efficacy of any specific approach to preventing or treating obesity. The USPSTF recommends that clinicians screen all adults for obesity and offer intensive counseling and behavioral interventions for optimal weight loss (USPSTF, 2003). In its 2003 review of the evidence, the USPSTF found that the most effective interventions combine nutrition education and diet and exercise counseling with behavioral strategies to increase physical activity and help change eating habits.

Knowledge vs. Practice

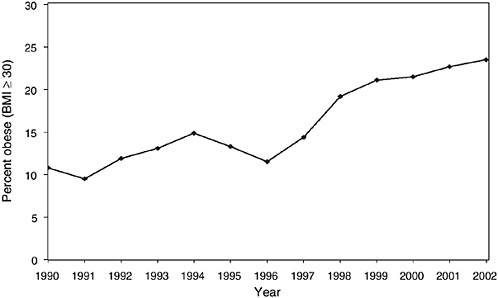

Adult obesity rates have been steadily increasing in Georgia, rising from under 11 percent in 1990 to almost 24 percent in 2002 (Figure 3-1) (CDC, 2003). Despite this epidemic of obesity in Georgia and elsewhere in the United States, it appears that health care providers rarely counsel their patients regarding weight issues. In Georgia, the vast majority (81.8 percent) of adults in 2000, overweight or not, reported that they did not get

|

2 |

A BMI calculator is available at www.nhlbisupport.com/bmi. |

FIGURE 3-1 Obesity by body mass index, Georgia, 1990-2002.

SOURCE: CDC, 2003.

professional advice about weight control in the previous year (CDC, 2004a). It is not known whether Georgians were more likely to receive professional advice about their weight if they were obese. Nationally, about 43 percent of obese persons say that a health care professional had advised them to lose weight during a routine checkup in the previous year (Mokdad et al., 2001).

Cancer Incidence Rates

The IOM committee recommends that GCC routinely monitor the overall incidence of cancer as well as the specific incidence of breast, colorectal, lung, and prostate cancers (see below).

-

Measure 3-6—Cancer incidence rate (all sites)

-

Measure 3-7—Breast cancer incidence rate

-

Measure 3-8—Colorectal cancer incidence rate

-

Measure 3-9—Lung cancer incidence rate

-

Measure 3-10—Prostate cancer incidence rate

Cancer incidence rates are important measures of the burden of cancer in a population, usually expressed as the number of newly diagnosed cancers

TABLE 3-2 Incidence of the Four Leading Cancers in Georgia, by Sex, 2000

|

Cancer site |

Incidence rate (per 100,000)a |

Number of cases |

Percent |

|

Lung and bronchus |

|||

|

Male |

108.8 |

3,095 |

10 |

|

Female |

51.5 |

1,965 |

6 |

|

Breast (female) |

125.6 |

4,953 |

16 |

|

Colorectal |

|||

|

Male |

62.2 |

1,762 |

6 |

|

Female |

43.6 |

1,690 |

5 |

|

Prostate |

164.5 |

4,729 |

15 |

|

Subtotal |

— |

18,194 |

58 |

|

All cancers |

|

31,591 |

100 |

|

Male |

558.1 |

16,388 |

52 |

|

Female |

388.0 |

15,203 |

48 |

|

aAge-adjusted to year 2000 population. SOURCE: U.S. Cancer Statistics Working Group, 2003; NCI and CDC, 2004. |

|||

per 100,000 population at risk.3 The population used depends on the rate to be calculated. For cancer sites that occur in only one sex, the sex-specific population (e.g., males for prostate cancer) is used. Table 3-2 shows the estimated incidence of the four leading types of cancers in Georgia in 2000: breast, colorectal, lung, and prostate.

Incidence data are fundamental to planning and evaluating cancer control programs. If, for example, Georgia succeeds in significantly reducing smoking rates, real progress, over the long term, will be evident in the state’s cancer incidence data, especially for lung cancer. Similarly, if Georgia markedly improves the quality and prevalence of colorectal cancer screening, this will ultimately be apparent in a corresponding decline in the incidence of colorectal cancer. Some caution is required in interpreting incidence rates since, in the short term, incidence may appear to increase in underscreened populations or with the introduction of more sensitive screening techniques.

DATA SOURCES

The data for the 10 prevention-related quality-of-cancer-care measures recommended for Georgia may be drawn from two sources: population surveys and tumor registries. As shown in Table 3-3, some data sources are Georgia based and others are national.

The Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS), sponsored by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), will be an essential source of information on Georgians who are at risk for cancer because of smoking or dietary habits. The BRFSS is specifically designed to produce annual, state-level estimates of population trends in behaviors related to cancer and other diseases. BRFSS field operations are managed by state health departments, so Georgia will have considerable flexibility to exploit the full potential of the survey. Furthermore, national-level findings are available on the CDC website and will provide useful benchmarks for Georgia to assess its progress. The Georgia Youth Tobacco Survey will be essential to monitoring adolescent smoking rates. At present, the survey only targets adolescents enrolled in school. Georgia should consider expanding the survey to reach an especially vulnerable population, teenagers who do not attend school. Tumor registries are the principal data source for computing cancer incidence rates. Further information about potential data sources is presented in Chapter 2, Concepts, Methods, and Data Sources and in Appendixes A and B.

SUMMARY

The application of evidence-based preventive services could help reduce the burden of cancer in Georgia. A considerable body of research has shown, for example, that smoking cessation interventions such as brief, behavioral counseling and pharmacotherapy are effective in helping adult smokers quit and remain smoking-free for 1 year. In this chapter, the IOM committee has recommended 10 quality-of-cancer-care measures to gauge GCC’s success in closing the gap between what is known about cancer prevention and what is practiced in the common, everyday routines of Georgia’s physician offices.

TABLE 3-3 Potential Data Sources for Recommended Measures of the Quality of Cancer Prevention in Georgiaa

|

Quality Measure |

Potential Georgia-Based Data Sources |

Potential National Data Sources for Benchmarking and Comparison |

||||||

|

Georgia BRFSS |

GCCR and Georgia SEER |

Georgia Youth Tobacco Survey |

BRFSS |

Healthy People 2010 |

NHQR |

SEER |

YRBSS |

|

|

Smokers receive advice to quit |

|

|

|

● |

|

|

|

|

|

Pharmacotherapy to quit smoking |

|

|

|

● |

|

|

|

|

|

Adult smoking rate |

● |

|

|

● |

● |

● |

|

|

|

Adolescent smoking rate |

|

|

● |

|

● |

|

|

● |

|

Adult obesity rate |

● |

|

|

● |

|

|

|

|

|

Cancer incidence rates |

|

● |

|

|

● |

● |

● |

|

|

aSee Chapter 2, Concepts, Methods, and Data Sources, and Appendixes A and B for descriptions of data sources. NOTE: BRFSS = Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System; GCCR = Georgia Comprehensive Cancer Registry; SEER = Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results; NHQR = National Healthcare Quality Report; YRBSS =Youth Risk Behavioral Surveillance System. The symbol ● indicates data are currently available. The symbol |

||||||||

QUALITY MEASURE SPECIFICATIONS: PREVENTING CANCER

The following section contains summary descriptions of the quality indicators presented in this chapter. These quality indicators were drawn from a variety of clinical practice setting organizations, federal programs, provider groups, and other sources. See Appendix A for descriptions of each of these organizations, including their classification schemes for grading clinical recommendations and characterizing evidence.

|

Measure 3-1. |

Adult Smoking Rate |

|

Measure 3-2. |

Adolescent Smoking Rate |

|

Measure 3-3. |

Smokers Who Receive Advice to Quit |

|

Measure 3-4. |

Smokers Who Are Recommended Pharmacotherapy to Assist in Quitting Smoking |

|

Measure 3-5. |

Adult Obesity Rate |

|

Measure 3-6. |

Cancer Incidence Rate (All Sites) |

|

Measure 3-7. |

Breast Cancer Incidence Rate |

|

Measure 3-8. |

Colorectal Cancer Incidence Rate |

|

Measure 3-9. |

Lung Cancer Incidence Rate |

|

Measure 3-10. |

Prostate Cancer Incidence Rate |

MEASURE 3-1: PREVENTING CANCER—Adult Smoking Rate

|

Description |

Adult smoking rate |

|

Source |

Healthy People 2010 |

|

Consensus on care |

Cigarette smoking is a major risk factor for lung cancer and contributes to the development of other types of cancer. Nonsmokers should be discouraged from starting. Intensive tobacco counseling and pharmacotherapy have been shown to be safe and effective in helping current smokers to quit. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force strongly recommends that clinicians screen all adults for tobacco use and provide tobacco cessation interventions for those who use tobacco products (Category A recommendation). |

|

Knowledge vs. practice |

Tobacco use accounts for at least 30 percent of all cancer deaths and 87 percent of lung cancer deaths in Georgia. In 2002, 23.2 percent of adults in Georgia smoked cigarettes. |

|

Approach to calculating the measure |

|

|

Numerator |

Number of adults who smoke cigarettes |

|

Denominator |

Number of adults |

|

Potential data source(s) |

Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System |

|

Comments |

Adjusted to year 2000 population standard. Adults include all persons age 18 and older. |

|

Limitations |

Potential response bias. |

|

Potential benchmark source(s) |

Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System; Healthy People 2010 |

|

Key references |

GDPH. 2004. OASIS Web Query—Death Statistics. [Online] http://oasis.state.ga.us/webquery/death.html [accessed April 2004]. IOM. 2003. Fulfilling the Potential of Cancer Prevention and Early Detection. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. Martin LM, et al. 2004. Georgia Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2002 Report. Atlanta, GA: Georgia Department of Human Resources. Publication Number DPH04-158HW. U.S. DHHS. 2000. Healthy People 2010: Understanding and Improving Health. Chapter 27. Tobacco Use. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: U.S. GPO. [Measure 27-1a.] USPSTF. 2002. Guide to Clinical Preventive Services. Counseling to Prevent Tobacco Use and Tobacco-Caused Disease. Rockville, MD: AHRQ. |

MEASURE 3-2: PREVENTING CANCER—Adolescent Smoking Rate

|

Description |

Adolescent smoking rate |

|

Source |

Healthy People 2010 |

|

Consensus on care |

Smoking should be discouraged among adolescents. Most adult smokers had their first cigarette before age 18, and more than half were daily smokers by age 18. There is evidence that if tobacco use does not begin in childhood or adolescence, it is unlikely to start in adulthood. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force finds limited evidence that counseling adolescents in the primary care setting is effective in preventing adolescent smoking or in helping adolescents to quit. |

|

Knowledge vs. practice |

In 2001, 23.7 percent of Georgia high school students and 8.9 percent of Georgia middle school students reported smoking cigarettes in the last 30 days. |

|

Approach to calculating the measure |

|

|

Numerator |

Number of students in grades 9 through 12 who smoked cigarettes on one or more of the previous 30 days |

|

Denominator |

Number of students in grades 9 through 12 |

|

Potential data source(s) |

Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System; Youth Tobacco Survey |

|

Comments |

— |

|

Limitations |

Data only reflect the subset of adolescents enrolled in high school; thus, adolescents at greatest risk are missed (i.e. high school dropouts, younger or older teens). Potential response bias. |

|

Potential benchmark source(s) |

Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System; Healthy People 2010 |

|

Key references |

ASCO. 2003. American Society of Clinical Oncology policy statement update: tobacco control—reducing cancer incidence and saving lives. J Clin Oncol. 21(14): 2777-86. Kanny D, et al. 2002. Georgia Youth Tobacco Survey, 2001. Atlanta, GA: Georgia Department of Human Resources. Publication Number DPH02.72HW. National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. 2003. YRBSS Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System. [Online] Available: http://www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/dash/yrbs/index.htm [accessed August 26, 2004]. U.S. DHHS. 2000. Healthy People 2010: Understanding and Improving Health. 2nd ed. Chapter 27. Tobacco Use. Washington, DC: U.S. GPO. [Measure 27-2b.] USPSTF. 2002. Guide to Clinical Preventive Services. Counseling to Prevent Tobacco Use and Tobacco-Caused Disease. Rockville, MD: AHRQ. |

MEASURE 3-3: PREVENTING CANCER—Smokers Who Receive Advice to Quit

|

Description |

Smokers who receive advice to quit |

|

Source |

National Healthcare Quality Report; Health Employer Data Information Set |

|

Consensus on care |

Many of the health risks associated with smoking are reduced after quitting. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force strongly recommends that clinicians screen all adults for tobacco use and provide tobacco cessation interventions for those who use tobacco (Category A recommendation). USPSTF found “good evidence” that, compared with no intervention, brief smoking cessation interventions, including screening, brief behavioral counseling (< 3 minutes), and pharmacotherapy delivered in primary care settings, are effective in helping smokers quit smoking and remain smoking-free after 1 year. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Public Health Service reports that quit rates are directly related to the intensity of counseling (Strength of Evidence grade A). |

|

Knowledge vs. practice |

In 2002, 23.2 percent of adults in Georgia smoked cigarettes. National data indicate that in 2000, 62 percent of smokers who had a routine office visit reported that their doctors had advised them to quit. |

|

Approach to calculating the measure |

|

|

Numerator |

Number of adult smokers who were advised to quit smoking during a visit with a doctor, nurse, or other health professional in the past year |

|

Denominator |

Adults who smoke and who saw a doctor, nurse, or other health professional in the past year |

|

Potential data source(s) |

Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System |

|

Comments |

— |

|

Limitations |

Potential recall and response bias. |

|

Potential benchmark source(s) |

National Healthcare Quality Report; Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System |

|

Key references |

AHRQ. 2003. National Healthcare Quality Report. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Fiore MC, et al. 2000. Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence. Clinical Practice Guideline. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service. GDPH. 2004. OASIS Web Query—Death Statistics. [Online] http://oasis.state.ga.us/webquery/death.html [accessed April 2004]. Martin LM, et al. 2004. Georgia Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2002 Report. Alanta, GA: Georgia Department of Human Resources. Publication Number DPH04/158HW. NCQA. 2004. Advising Smokers to Quit. [Online] Avaiable: http://www.ncqa.org/programs/radd/expanded%20web%20version/advising_smokers_to_quit.htm#Measure [accessed August 2004]. |

MEASURE 3-4: PREVENTING CANCER—Smokers Who Are Recommended Pharmacotherapy to Assist in Quitting Smoking

|

Description |

Smokers who are recommended pharmacotherapy to assist in quitting smoking |

|

Source |

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF); U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service (Strength of Evidence grade A) |

|

Consensus on care |

Many of the health risks associated with smoking are reduced after quitting. The USPSTF strongly recommends that clinicians screen all adults for tobacco use and provide tobacco cessation interventions for those who use tobacco (Category A recommendation). USPSTF found “good quality” studies documenting higher quitting rates among people who use nicotine replacement products compared with people who do not. There are numerous Food and Drug Administration-approved pharmacotherapies, such as nicotine gum, nicotine transdermal patches, inhalers, and nasal sprays that have been shown to be safe and effective for treating tobacco dependence. |

|

Knowledge vs. practice |

In 2002, 23.2 percent of adults in Georgia smoked cigarettes. |

|

Approach to calculating the measure |

|

|

Numerator |

Number of adult smokers whose doctor, nurse, or other health professional recommended or discussed medication to assist quitting smoking in the past year |

|

Denominator |

All adult smokers |

|

Potential data sources |

Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System |

|

Comments |

Adults include all persons aged 18 and older. |

|

Limitations |

It is uncertain whether tobacco cessation pharmacotherapy is safe and effective for pregnant women, nursing mothers, children, and adolescents. The measure does not capture advice given to younger smokers. Potential recall and response bias. |

|

Potential benchmark source(s) |

Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System |

|

Key references |

CDC. 2004. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System: Questionnaires. [Online] Available at http://www.cdc.gov/brfss/questionnaires/questionnaires.htm [accessed November 26, 2004. Fiore MC, et al. 2000. Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence. Clinical Practice Guideline. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service. GDPH. 2004. OASIS Web Query—Death Statistics. [Online] http://oasis.state.ga.us/webquery/death.html [accessed April 2004]. Martin LM, et al. 2004. Georgia Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2002 Report. Atlanta, GA: Georgia Department of Human Resources. Publication Number DPH04/158HW. NCQA. 2004. Advising Smokers to Quit. [Online] Avaiable: http://www.ncqa.org/programs/radd/expanded%20web%20version/advising_smokers_to_quit.htm#Measure [accessed August 2004]. USPSTF. 2002. Guide to Clinical Preventive Services. Counseling to Prevent Tobacco Use and Tobacco-Caused Disease. Rockville, MD: AHRQ. |

MEASURE 3-5: PREVENTING CANCER—Adult Obesity Rate

|

Description |

Adult obesity rate |

|

Source |

Healthy People 2010 |

|

Consensus on care |

Body mass index (BMI) is defined as weight in kilograms divided by square of the height in meters (BMI = weight[kg]/ height[m2]). Obesity is defined as a BMI of 30 or more. Obesity is a risk factor for some types of cancers, including breast and colorectal cancer. According to the International Agency on Research in Cancer, about 10 percent of breast and colorectal cancers may be attributable to overweight and obesity. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends that all clinicians screen all adults for obesity and offer intensive counseling and behavioral interventions (Category B recommendation). It is a goal of Healthy People 2010 to reduce the proportion of adults who are obese. |

|

Knowledge vs. practice |

In Georgia, 23.5 percent of adults are obese, and obesity rates vary by race, 20.7 percent of whites compared with 31.2 percent of blacks. |

|

Approach to calculating the measure |

|

|

Numerator |

Number of adults aged 18 and older who have a BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 |

|

Denominator |

Number of adults aged 18 and older |

|

Potential data source(s) |

Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System |

|

Comments |

BMI is calculated from self-reported height and weight. |

|

Limitations |

Cancer-related health risks from obesity past age 74 are unclear. Potential recall and response bias. |

|

Potential benchmark source(s) |

Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System; Healthy People 2010 |

|

Key references |

IOM. 2003. Fulfilling the Potential of Cancer Prevention and Early Detection. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. Martin LM, et al. 2004. Georgia Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2002 Report. Atlanta, GA: Georgia Department of Human Resources. Publication Number DPH04/158HW. McTigue KM, et al. 2003 Screening and interventions for obesity in adults: summary of the evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 139(11):933-949. U.S. DHHS. 2000. Healthy People 2010: Understanding and Improving Health. 2nd ed. Chapter 19 Nutrition and Overweight. Washington, DC: U.S. GPO. [Measure 19-2.] USPSTF. 2003. Screening for Obesity in Adults. What’s New from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Rockville, MD: AHRQ. |

MEASURE 3-6: PREVENTING CANCER—Cancer Incidence Rate (All Sites)

|

Description |

Cancer incidence rate (all sites) |

|

Source |

Routine surveillance statistic |

|

Consensus on care |

Incidence statistics are key to monitoring overall cancer burden and the health care system’s capacity to meet the need for services. |

|

Knowledge vs. practice |

In 2000, Georgia’s cancer incidence rates were 558.1 per 100,000 and 388.0 per 100,000 for males and females, respectively. Nationally they were 546.9 per 100,000 and 409.4 per 100,000. |

|

Approach to calculating the measure |

|

|

Numerator |

Number of new cancer cases |

|

Denominator |

Total Georgia population |

|

Potential data source(s) |

Georgia Comprehensive Cancer Registry |

|

Comments |

Incidence rate = (New cancers/Population) × 100,000. Estimate should be age-adjusted to allow comparisons. |

|

Limitations |

Increasing incidence may reflect improvements in screening rates and technologies rather than a real increase in cancer. Incidence is a long-term indicator; substantial time must pass before GCC would have any impact on breast cancer incidence. Incidence is not a full measure of the burden of cancer and ignores duration, mortality, quality of life, and other factors. |

|

Potential benchmark source(s) |

Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program, U.S. Cancer Statistics publications |

|

Key references |

U.S. Cancer Statistics Working Group. 2003. United States Cancer Statistics: 2000 Incidence. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and National Cancer Institute. |

MEASURE 3-7: PREVENTING CANCER—Breast Cancer Incidence Rate

|

Description |

Breast cancer incidence rate |

|

Source |

Routine surveillance statistic |

|

Consensus on care |

Incidence statistics are key to monitoring cancer burden and the health care system’s capacity to meet the need for services. |

|

Knowledge vs. practice |

In 2000, Georgia’s breast cancer incidence rate was 125.6 per 100,000; nationally it was 128.9 per 100,000. |

|

Approach to calculating the measure |

|

|

Numerator |

Number of new breast cancer cases |

|

Denominator |

Number of females in Georgia |

|

Potential data source(s) |

Georgia Comprehensive Cancer Registry |

|

Comments |

Incidence rate = (New cancers/Population) × 100,000. Estimate should be age-adjusted to allow comparisons. |

|

Limitations |

Increasing incidence may reflect improvements in screening rates and technologies rather than a real increase in breast cancer, so incidence statistics may need to be interpreted with stage and mortality statistics. Incidence is a long-term indicator; substantial time must pass before GCC would have any impact on cancer incidence. |

|

Potential benchmark source(s) |

Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program; U.S. Cancer Statistics publications |

|

Key references |

U.S. Cancer Statistics Working Group. 2003. United States Cancer Statistics: 2000 Incidence. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and National Cancer Institute. |

MEASURE 3-8: PREVENTING CANCER—Colorectal Cancer Incidence Rate

|

Description |

Colorectal cancer incidence rate |

|

Source of measure |

Routine surveillance statistic |

|

Consensus on care |

Recent studies show an association between colorectal cancer screening and decreased incidence of and mortality from colorectal cancer. Survey data suggest that colorectal cancer screening rates in Georgia fall far short of recommended levels. |

|

Knowledge vs. practice |

In 2000, Georgia’s colorectal cancer incidence rates were 62.2 per 100,000 and 43.6 per 100,000 for males and females, respectively. Nationally, they were 65.0 per 100,000 and 47.0 per 100,000. |

|

Approach to calculating the measure |

|

|

Numerator |

Number of new colorectal cancer cases |

|

Denominator |

Total Georgia population |

|

Potential data source(s) |

Georgia Comprehensive Cancer Registry |

|

Comments |

Incidence rate = (New cancers/Population) × 100,000. Estimate should be age-adjusted to allow comparisons. |

|

Limitations |

Increasing incidence may reflect improvements in screening rates and technologies rather than a real increase in colorectal cancer, so incidence statistics may need to be interpreted with stage and mortality statistics. Incidence rates are long-term indicators; substantial time must pass before GCC would have any impact on colorectal cancer incidence. |

|

Potential benchmark source(s) |

Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program; U.S. Cancer Statistics publications |

|

Key references |

CDC. 2004. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, Prevalence Data: Georgia 2002 Colorectal Cancer Screening. [Online] Available: http://apps.nccd.cdc.gov/brfss/display.asp?cat=CC&yr=2002&qkey=7400&state=GA [accessed November 26, 2004]. IOM. 2003. Fulfilling the Potential of Cancer Prevention and Early Detection. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. U.S. Cancer Statistics Working Group. 2003. United States Cancer Statistics: 2000 Incidence. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and National Cancer Institute. |

MEASURE 3-9: PREVENTING CANCER—Lung Cancer Incidence Rate

|

Description |

Lung cancer incidence rate |

|

Source |

Routine surveillance statistic |

|

Consensus on care |

More than 80 percent of lung cancers can be attributed to smoking. Lung cancer incidence in Georgia should drop if GCC succeeds in lowering smoking rates. |

|

Knowledge vs. practice |

In 2000, Georgia’s lung cancer incidence rates were 108.0 per 100,000 and 51.5 per 100,000 for males and females, respectively. Nationally, they were 87.9 per 100,000 and 51.5 per 100,000. |

|

Approach to calculating the measure |

|

|

Numerator |

Number of new lung cancer cases |

|

Denominator |

Total Georgia population |

|

Potential data source(s) |

Georgia Comprehensive Cancer Registry |

|

Comments |

Incidence rate = (New cancers/Population) × 100,000. Estimate should be age-adjusted to allow comparisons. |

|

Limitations |

Incidence rates are long-term indicators; substantial time must pass before GCC would have any impact on lung cancer incidence. |

|

Potential benchmark source(s) |

Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program; U.S. Cancer Statistics publications |

|

Key references |

IOM. 2003. Fulfilling the Potential of Cancer Prevention and Early Detection. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. Martin LM, et al. 2004. Georgia Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2002 Report. Atlanta, GA: Georgia Department of Human Resources. Publication Number DPH04/158HW. U.S. Cancer Statistics Working Group. 2003. United States Cancer Statistics: 2000 Incidence. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and National Cancer Institute. |

MEASURE 3-10: PREVENTING CANCER—Prostate Cancer Incidence Rate

|

Description |

Prostate cancer incidence rate |

|

Source |

Routine surveillance statistic |

|

Consensus on care |

Incidence statistics are key to monitoring cancer burden and the health care system’s capacity to meet the need for services. |

|

Knowledge vs. practice |

In 2000, Georgia’s prostate cancer incidence rate was 164.5 per 100,000; nationally, it was 160.4 per 100,000. |

|

Approach to calculating the measure |

|

|

Numerator |

Number of new prostate cancer cases |

|

Denominator |

Number of males in Georgia |

|

Potential data source(s) |

Georgia Comprehensive Cancer Registry |

|

Comments |

Incidence rate = (New cancers/Population) × 100,000. Estimate should be age-adjusted to allow comparisons. |

|

Limitations |

Increasing incidence may reflect improvements in screening rates and technologies rather than a real increase in prostate cancer, so incidence statistics may need to be interpreted with stage and mortality statistics. Incidence rates are long-term indicators; substantial time must pass before GCC would have any impact on prostate cancer incidence. |

|

Potential benchmark source(s) |

Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program; U.S. Cancer Statistics publications |

|

Key references |

U.S. Cancer Statistics Working Group. 2003. United States Cancer Statistics: 2000 Incidence. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and National Cancer Institute. |

REFERENCES

ACS (American Cancer Society). 2004. Cancer Facts & Figures 2004. Atlanta, GA: ACS.

AHRQ (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality). 2003. National Healthcare Quality Report. Rockville, MD: U.S. DHHS.

Alberg AJ, Samet JM. 2003. Epidemiology of lung cancer. Chest. 123(1 Suppl): 21S-49S.

ASCO (American Society for Clinical Oncology). 2003. American Society of Clinical Oncology policy statement update: tobacco control—reducing cancer incidence and saving lives. J Clin Oncol. 21(14): 2777-86.

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2000. Strategies for reducing exposure to environmental tobacco smoke, increasing tobacco use cessation, and reducing initiation in communities and health-care systems. A report on recommendations of the Task Force on Community Preventive Services. MMWR. 49(RR-12).

——. 2003. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, Trends Data, Georgia, Obesity: By Body Mass Index. [Online] Available: http://apps.nccd.cdc.gov/brfss/Trends/trendchart.asp?qkey=10010&state=GA [accessed November 26, 2004].

——. 2004a. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, Prevalence Data: Georgia 2000, Weight Control. [Online] Available: http://apps.nccd.cdc.gov/brfss/display.asp?cat=WC&yr=2000&qkey=4390&state=GA [accessed November 26, 2004].

——. 2004b. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, Prevalence Data: Georgia 2002 Colorectal Cancer Screening. [Online] Available: http://apps.nccd.cdc.gov/brfss/display.asp?cat=CC&yr=2002&qkey=7400&state=GA [accessed November 26, 2004].

——. 2004c. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System: Questionnaires. [Online] Available: http://www.cdc.gov/brfss/questionnaires/questionnaires.htm [accessed November 26, 2004].

Fiore MC, Bailey, WC, Cohen, SJ, Dorfman SF, Goldstein MG, Gritz ER, Hegman RB, Jaen CR, Kuttlee TE, Lando HA, Mecklenburg RE, Mullen PD, Nett LM, Robinson L, Stitzer ML, Tomasello AC, Villejo L, Wiwers ME, Baker T, Fox BJ, Hasselblad V. 2000. Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence. Clinical Practice Guideline. Rockville, MD: U.S. DHHS, Public Health Service.

Friedenreich CM. 2001. Physical activity and cancer prevention: from observational to intervention research. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 10(4): 287-301.

GCC (Georgia Cancer Coalition). 2001. Strategic Plan. Atlanta, GA: GCC.

——. 2003. Mobilizing Georgia, Immobilizing Cancer. Atlanta, GA: GCC.

GDPH (Georgia Division of Public Health). 2004. OASIS Web Query—Death Statistics. [Online] Available: http://oasis.state.ga.us/webquery/death.html [accessed April 2004].

Hopkins DP, Briss PA, Ricard CJ, Husten CG, Carande-Kulis VG, Fielding JE, Alao MO, McKenna JW, Sharp DJ, Harris JR, Woollery TA, Harris KW. 2001. Reviews of evidence regarding interventions to reduce tobacco use and exposure to environmental tobacco smoke. Am J Prev Med. 20(2 Suppl): 16-66.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2003. Fulfilling the Potential of Cancer Prevention and Early Detection. Curry S, Byers T, Hewitt M, Editors. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Kanny D, Powell KE, Copes K. 2002. Georgia Youth Tobacco Survey, 2001. Atlanta, GA: Georgia Department of Human Resources, Division of Public Health, Tobacco Use Prevention Section.

Key TJ, Schatzkin A, Willett WC, Allen NE, Spencer EA, Travis RC. 2004. Diet, nutrition and the prevention of cancer. Public Health Nutr. 7(1A): 187-200.

Kritchevsky D. 2003. Diet and cancer: what’s next? J Nutr. 133(11 Suppl 1): 3827S-3829S.

Martin LM, Chowdhury PP, Powell KE, Clanton J. 2004. Georgia Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2002 Report. Atlanta, GA: Georgia Department of Human Resources, Division of Public Health, Chronic Disease, Injury, and Environmental Epidemiology Section.

McTigue KM, Harris R, Hemphill B, Lux L, Sutton S, Bunton AJ, Lohr KN. 2003. Screening and interventions for obesity in adults: summary of the evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 139(11): 933-49.

Mokdad AH, Bowman BA, Ford ES, Vinicor F, Marks JS, Koplan JP. 2001. The continuing epidemics of obesity and diabetes in the United States. JAMA. 286(10): 1195-2000.

National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. 2003. YRBSS Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System. [Online] Available: http://www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/dash/yrbs/index.htm [accessed August 26, 2004].

NCI and CDC (National Cancer Institute and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2004. State Cancer Profiles. [Online] Available: http://statecancerprofiles.cancer.gov/incidencerates/incidencerates.html [accessed July 9, 2004].

NCQA (National Committee for Quality Assurance). 2004. Advising Smokers to Quit. [Online] Available: http://www.ncqa.org/programs/radd/expanded%20web%20version/advising_smokers_to_quit.htm#Measure [accessed August 2004].

Peto R, Darby S, Deo H, Silcocks P, Whitley E, Doll R. 2000. Smoking, smoking cessation, and lung cancer in the UK since 1950: combination of national statistics with two case-control studies. BMJ. 321(7257): 323-9.

U.S. Cancer Statistics Working Group. 2003. United States Cancer Statistics: 2000 Incidence. Atlanta, GA: U.S. DHHS, CDC, and NCI.

U.S. DHHS (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services). The Health Benefits of Smoking Cessation. Rockville, MD: U.S. DHHS, Public Health Service, Centers for Disease Control, Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office of Smoking and Health. DHHS Publication No. (CDC) 90-8416.

——. 1994. Preventing Tobacco Use Among Young People: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, CDC, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health.

——. 2000. Healthy People 2010: Understanding and Improving Health. 2nd edition. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

——. 2004. The Health Consequences of Smoking: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: U.S. DHHS, CDC, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office of Smoking and Health.

USPSTF (U.S. Preventive Services Task Force). 2002. Guide to Clinical Preventive Services. Counseling to Prevent Tobacco Use and Tobacco-Caused Disease. Rockville, MD: AHRQ.

——. 2003. Screening for Obesity in Adults. What’s New from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Rockville, MD: AHRQ.

Vainio H, Bianchini F. 2002. IARC Handbooks of Cancer Prevention. Volume 6: Weight Control and Physical Activity. Lyon, France: IARC Press.