3

THE FOOD AND DRUG ADMINISTRATION

Introduction

This chapter of this background paper describes the Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) statutory authority and responsibility for new therapeutics, FDA programs begun as a result of legislative mandates or through the initiative of the agency itself, and interactions with sponsors and other entities, in particular, the National Cancer Institute (NCI). Not discussed (and the subject of a separate ongoing Institute of Medicine study) is post-marketing surveillance of drugs after development and FDA approval.

The FDA implements the laws passed by Congress relating to the approval and regulation of drugs and biological products in the United States; regulating clinical research on new drugs and biologics through the investigational new drug (IND) procedures; approving the marketing of new products for specific indications once safety and efficacy have been demonstrated in a New Drug Application (NDA; or a Biologics License Application (BLA) for biologics); and monitoring the safety of products following approval. In addition, the FDA regulates medical devices, veterinary drugs, food and food additives, and cosmetics and has special programs to encourage drug development for rare diseases and for children and procedures to allow patients with life-threatening diseases access to unapproved drugs.

Although few of the statutory provisions carried out by the FDA relate specifically to cancer, dedicated groups within FDA have been assigned to specific disease areas, including cancer; cancer-specific advisory bodies and guidance documents have helped to customize and standardize procedures for cancer drugs; and procedures for accelerated or conditional approvals of products have become increasingly important for cancer drugs—more so than for any other disease category.

The time that passes in the course of FDA review of INDs and NDAs is short relative to total R&D time (said to be 5–10 percent of total clinical development time), but FDA regulations govern much of what happens during the development and testing of new treatments by sponsors and in their preparation of documentation to meet FDA requirements (Hirschfeld and Pazdur, 2002). The duration of FDA review has decreased dramatically since 1992 with enactment of reforms mandated in the laws instituting user fees and changes allowing the provisional, accelerated approval of new drugs that reduce the amount of information required at the time of approval with the expectation that studies filling in the information base will be completed thereafter. These processes reflect the FDA’s mission to protect the public’s health by ensuring both safe and effective drugs and timely entry of those drugs into the market place and patient care.

History

As noted, new drugs may be sold in the United States only after they receive FDA approval—based on adequate evidence that they are safe and effective in humans that is developed using study methods that meet criteria set out in PDA regulations. The FDA’s authority derives from laws passed by the Congress. This includes mainly the Federal Food Drug and Cosmetic Act (FDCA) and its amendments, but others as well, such as the Public Health Service Act (dealing with biologics, among other things), the Federal Advisory Committee Act (which allows FDA to ask outside expert advice provided it is through properly chartered advisory committees), and other legislation that is significant, but narrower in scope.

The original Food and Drug Act of 1906 was enforced by FDA’s precursor, the Bureau of Chemistry in the U.S. Department of Agriculture and was primarily concerned with misbranded and adulterated food and drugs in interstate commerce. The next major milestone, the FDCA was enacted in 1938. It only authorized the FDA to require evidence from sponsors that drugs were safe before they could be sold, but the Kefauver-Harris amendments of 1962 added a requirement for FDA pre-market approval with determination of both safety and efficacy on the basis of evidence provided by the sponsor. Currently, the Act requires that there be “substantial evidence that the drug will have the effect it purports or is represented to have under the conditions of use prescribed, recommended, or suggested in the proposed labeling…” (U.S. Food and Drug Administration, 1998). The Orphan Drug amendments to the FDCA in 1983 and three subsequent years provide special encouragement for development of drugs for uneconomic markets (usually dealing with a prevalence of less than 200,000 people in the United States). About 40 oncology drugs have been approved with orphan designation, but the program was not intended to address approval criteria or review times (Roberts and Hirschfeld, 2005). More recent amendments are described in greater detail below.

The FDCA (as amended) prescribes the basic framework for the approval of new drugs, and over the years a large body of regulation has been developed by the FDA that provides the details of how drugs may be tested and the standards of evidence to which drug sponsors will be held. FDA regulations have the force of law when, after going through prescribed steps that include input from all interested parties in a public process that often takes several years to complete, they are published in the U.S. Code of Federal Regulations (CFR). The FDA has been reorganized as medical technologies have changed. Traditionally, separate centers for drugs, biologics, and devices (as well as other centers that deal with foods and cosmetics) have taken responsibility for different types of products. The centers developed different practices and policies geared toward the products they regulated and the legislation and regulations that applied to them.

Most existing cancer therapeutics are drugs (small molecules) and have been evaluated through the Division of Oncology Products of the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER or its predecessors). Over the last decade or two, biological products have been developed to treat cancer and cancer-related conditions, and, as a result, the FDA officially transferred responsibility for therapeutic biologic agents from the Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER) to CDER beginning in January

2003, with the intention that all drug-like agents would be reviewed using the same criteria and by the same staff. CBER would retain authority over vaccines, blood cells, tissues, gene therapy and related products. The change was to involve no reductions in personnel, but would require the transfer of selected people and resources. As of 2005, the integration of the personnel and resources involved in biologics reviews is incomplete. The reviews are technically carried out within CDER, but by the same staff as previously. Their office remains segregated from the main CDER oncology staff. How well the new system is working to minimize the variability that previously existed between reviews carried out by CBER and CDER is not clear.

The shift of responsibility for most biologics to CDER would consolidate responsibility for most cancer products into CDER’s Division of Oncology Products. Diagnostic tests for cancer are left in the Office of In Vitro Diagnostic Device Evaluation and Safety of the Center for Devices and Radiological Health (CDRH). One hope for newer agents is that evidence of specific activity at the molecular level will eventually be used to monitor treatment. However, these tests, although closely linked to the targeted agents themselves, would be regulated by a separate entity under the current organization. In view of progress in this direction and the likelihood that targeted agents will become more and more a reality, suggestions were recently made for further consolidation in cancer and even for FDA “selective approvals” contingent on post-marketing studies that enabled identification of subsets of cancer patients with molecular changes predicting response to treatment with specific targeted agents (Roberts and Chabner, 2004).

The Office of Oncology Drug Products (ODP)

Accordingly, in July 2004, FDA announced further changes to the agency’s organization with the objective of strengthening review of products to diagnose, treat, and prevent cancer. These changes had been preceded by years of discussions with cancer advocacy organizations, industry representatives, and NCI about the need to consolidate oncology expertise across the agency,15 and they followed several other changes FDA had recently made to cancer review, such as the formation of the FDA/NCI Interagency Oncology Task Force (see below) to enhance the efficiency of clinical research and the scientific evaluation of new cancer therapeutics.

Under the restructuring, a new Office of Oncology Drug Products (ODP) would oversee both traditional chemotherapies and biologically based treatments. The product scope also included hematologic therapies, radiation protection agents, medical imaging drugs, and radiographic agents used to diagnose, monitor, and treat cancer and other diseases. The rationale for the reorganization proposed that having all oncology products reviewed in one office could speed evaluation and promote the use of uniform scientific standards. However, it appears that cancer vaccines and cell-based therapies will remain in CBER and not be moved to ODP. The rationale for this policy is not clear in official FDA statements.

ODP was placed in CDER, given that division’s role in reviewing the majority of cancer products already, consolidating the three existing areas within CDER responsible for the review of drugs and therapeutic biologics used to diagnose, treat, and prevent cancer. The new ODP, therefore, would consist of three review divisions, although details are not final. Besides the drugs, the therapeutic biologic products included in ODP include recombinant therapeutic proteins and monoclonal antibodies.

FDA’s goal with the creation of this new office is to improve consistency of review and policy toward oncology drugs, and bring together a critical mass of oncologists who will help develop new therapies. ODP will also provide technical consultation between CDER and other FDA components, including CBER, CDRH, and the Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition (CFSAN). The Director of the Office of Oncology Drug Products, although not yet named as of the beginning of 2005, will have the authority to approve totally new cancer products. Most other drugs (for example, new dosage forms or new indications) will be approved by the division directors within ODP.

To support ODP and coordinate work performed throughout the various FDA product Centers related to cancer, FDA also created an Oncology Program housed in ODP. The Oncology Program will facilitate the consultation of FDA experts across the agency, provide a forum to discuss and develop regulatory policy and standards, and serve as a focal point for agency interaction and collaboration with NCI and other important stakeholders. This program will also coordinate cross-cutting training and oncology educational activities and will include an agency wide Oncology Coordinating Committee to ensure consistent FDA policies for anticancer drug and biologics.

The reorganization will be implemented in the spring of 2005. It does not change the legal standards for approval of drugs or devices, but it is designed to help facilitate the ongoing development of new standards as practice and science evolve. Part of this new standard setting is expected to emerge from the FDA/NCI Oncology Task Force described below.

The IND Process

Before an investigational, or unapproved, drug can be given to any human, the sponsor must apply to the FDA for an investigational new drug (IND) exemption16. While developing the IND, sponsors are encouraged, though not required, to meet with the FDA. During such meetings, the sponsor can solicit FDA’s views on the adequacy and interpretation of preclinical data and on clinical trial design. Pre-IND consultation improves the chances that the IND will be allowed. It is not binding on FDA during subsequent review of the development of the drug, but the special protocol assessment process described below does commit the FDA short of evident public health concerns. Furthermore, pre IND and end-of-phase II conferences have been shown to be associated

with shorter product development times compared to times of products that were not discussed (Roberts and Hirschfeld, 2005)

Before clinical testing, a sponsor must determine that a product is likely to have therapeutic benefit and establish that it will not expose humans to unreasonable risks when used in limited, early-stage studies. To this end, information is required in three broad areas:

1.) Animal pharmacology and toxicology studies—preclinical data, evaluated to assess whether the product is reasonably safe for initial testing in humans, including: a pharmacological profile of the drug; information on the acute toxicity of the drug in at least two species of animals; short-term toxicity studies ranging from two weeks to three months, depending on the proposed duration of use of the substance in the proposed clinical studies; and also previous (for example, foreign) experience with the drug in humans;

2.) Manufacturing information—information on the composition, manufacturer, stability, and controls used for making the product, evaluated to ensure that the company can produce and supply consistent batches of the drug;

3.) Clinical protocols and investigator information—detailed protocols for proposed clinical studies to assess whether initial-phase trials will expose subjects to unnecessary risks, information on the qualifications of clinical investigators (professionals, generally physicians, who oversee the administration of the experimental compound), and commitments to obtain informed consent from the research participants, to obtain review of the study by an institutional review board (IRB), and to adhere to the IND regulations.

Of the three types of INDs, the Investigator IND is the one involved in bringing a new drug to market. The Emergency Use IND allows FDA to authorize use of an experimental drug in an emergency situation that does not allow time for submission of an IND in accordance with the regulations. It is also used for patients who do not meet the criteria of an existing study protocol, or if there is no approved protocol. A Treatment IND is submitted to allow use of an unapproved, but promising, drug for serious or immediately life-threatening conditions in the final stages of formal clinical testing and FDA review. A fourth, “exploratory” IND is being considered by FDA (see the Critical Path section of this chapter). Once an investigator IND is submitted, the FDA has 30 days to review it and to notify the sponsor if it is determined that it cannot be approved. (http://www.fda.gov/cder/regulatory/applications/ind_page_1.htm#Introduction)

The NDA/BLA Process

The NDA or BLA is the sponsor’s formal proposal that the FDA approve a new pharmaceutical or biologic for sale and marketing in the United States. Technically, it is a proposal that FDA approve a claim about a drug not the drug itself. The data gathered during the animal studies and human clinical trials described in the IND become part of the NDA/BLA application. The goals of the NDA are to provide enough information to permit FDA reviewers to reach the following key decisions:

-

Whether the drug is safe and effective in its proposed use(s) and whether the benefits of the drug outweigh the risks.

-

Whether the drug’s proposed labeling (package insert) is appropriate and what it should contain.

-

Whether the methods used in manufacturing the drug and the controls used to maintain the drug’s quality are adequate to preserve the drug’s identity, strength, quality, and purity.

An NDA/BLA requires documentation of all relevant information about the drug or biologic, including the results of all animal, laboratory, and clinical studies; and the product’s chemical, biological and physical properties, and how it is manufactured, processed and packaged. From all this information, the FDA must be able to develop product labeling that defines the condition or conditions of use (specifying the patient population, as needed) and the appropriate doses and regimens.

The regulations that govern rules for approval state that safety and efficacy must be demonstrated by adequate and well-controlled trials. Safety and efficacy are not absolute values, however, and the general criterion for approval is evidence of a favorable risk-benefit profile. The general evaluation criteria used in oncology are

-

improved survival,

-

palliation of symptoms with no decrease in survival,

-

protection against adverse events with no decrease in survival, or

-

a reduction in the risk of developing cancer.

(Hirschfeld and Pazdur, 2002)

FDA staff with a range of technical expertise undertake an independent analysis of the clinical trial data. The final assessment balances the positive effects (benefits) of the agent against the toxicities and other adverse events (risks) reported according to their type, frequency, severity, duration, and clinical consequences.

The Oncologic Drugs Advisory Committee (ODAC)

The Oncologic Drugs Advisory Committee (ODAC) is a body of 12 non-governmental advisors serving staggered 4-year terms that provides independent external advice to FDA on approval decisions for oncologic drug NDAs. ODAC also has a statutorily mandated pediatric oncology subcommittee. In accordance with its charter, at least one member of ODAC is a patient representative, one a consumer representative, and one a statistician. Other experts are brought in to advise ODAC as called for by the task at hand. An ODAC meeting is usually called a few months after FDA receives an NDA and has conducted its initial analyses and shared them with ODAC, although not all

reviews for licensing applications are brought to ODAC. At the meetings, which are open to the public, both the sponsor and FDA present their findings to, and are queried by, ODAC members. After consideration and discussion of the evidence, ODAC votes on whether to advise approval. FDA is not bound by ODAC advice, but the agency usually follows it.

Evidence Required for Approval

As noted earlier, Congress amended the FDCA in 1962 to require for the first time that sponsors demonstrate the effectiveness in addition to the safety of their products through “substantial evidence” from “adequate and well-controlled investigations” before FDA could approve them for marketing. Since clinical trials are time-consuming and expensive, it is in both the public’s and the sponsor’s interest to conduct trials efficiently and quickly to develop “substantial” evidence through “adequate investigations.”

Based on the 1962 amendment’s legislative language and debates, FDA generally regards adequate and well-controlled investigations to mean at least two studies, each convincing, although at times a single excellent study accompanied by supporting evidence from studies of related questions (for example, a different dosage form, a different but related indication) has been deemed sufficient. This interpretation was codified in the FDA Modernization Act (FDAMA) of 1997 (section 115(a), amending section 505(d) of the FDCA), which states that, if so judged by the FDA, effectiveness may be established by “data from one adequate and well-controlled clinical investigation and confirmatory evidence” (U.S. Food and Drug Administration, 1998).

Before 1972, NIH’s Bureau of Biologics was responsible for review of biologics and required a demonstration of “continued safety, purity, and potency” (as defined in the Public Health Services Act). Thereafter, the FDA assumed responsibility for review of the safety and effectiveness of biological products and approval of those agents has been held to the same standard as drugs: adequate and well-controlled studies. FDAMA reinforced this practice, directing the agency to take measures to “minimize differences in the review and approval” of biologic and drug products (U.S. Food and Drug Administration, 1998).

The Prescription Drug User Fee Act17

In the 1970s and 1980s, concerns were expressed by the pharmaceutical industry and sympathetic academics regarding the duration of FDA NDA reviews. The “drug lag” debate held that U.S. reviews were slower than those in the United Kingdom and certain European countries, and yet, faster times to market in such countries resulted in little evidence of harm and claims of greater benefit through earlier availability. The 1992 Prescription Drug User Fee Act (PDUFA) addressed that critique, not by relaxing any FDA regulatory requirements, but by responding to FDA’s position that long review times resulted from insufficient funds to hire enough reviewers. PDUFA codified:

industry acceptance of user fees on NDA and other submissions; FDA agreement to performance goals for reviews of applications; and congressional agreement that user fee revenue would not substitute for appropriations (and limitation of PDUFA legislative authority to 5 years). It was thus agreed that the funds supporting reviews could not fall below 1992 (later 1997) levels adjusted for inflation. This has had the effect, over time, of requiring resource shifting from other FDA activities.

Although, the idea of user fees was not new in the 1990s, by then both Congress and the pharmaceutical industry had begun to appreciate and accept FDA’s position on increasing workload demands, both because of greater numbers and increased complexity of applications (Shulman and Kaitin, 1996). PDUFA was subsequently reauthorized in FDAMA (“PDUFA II”) and again in the Public Health Security and Bioterrorism Preparedness and Response Act in 2002 (“PDUFA III”), with each reauthorization adding new goals and provisions. These laws authorized substantial fee collections, for example, the five year PDUFA III plan estimates receipts of a little over $1.25 billion total and FDA actually received approximately $825 million from drug and biologic manufacturers from fiscal years 1993 through 2001 (US GAO, .2002).

Performance Goals

User fees apply to prescription drugs, including most biologicals, and to over-the-counter (OTC) products that are the subject of an NDA. Exemptions include blood and blood products, in vitro diagnostics, other biologicals, and generic drugs. There are three types of fees: application fees, annual product fees, and annual establishment fees. Application fees apply to NDAs, Product License Applications (PLAs, required of biologicals), supplemental applications (for example, a new indication or labeling change), and prescription-to-OTC applications (Shulman and Kaitin, 1996).

In return for user fees, FDA agreed to certain performance goals, negotiated between the FDA Commissioner and the chairmen of the relevant congressional committees. PDUFA set performance goals for review times for both standard approvals and priority approvals, as follows:

-

For standard NDAs and applications to add indications to the labeling (supplements) with clinical data, FDA agreed to review and act on 90 percent of such applications within twelve months from the date of submission. The current goal was set by PDUFA II, which amended this to 90 percent of such applications acted on within ten months. “Review and act on” meant that FDA would complete a comprehensive review of an application and issue an FDA action letter. An action letter might indicate approval, but it might also indicate deficiencies to be remedied, some potentially by more data or analyses, some not. Sponsor response to the agency action letter would restart the clock.

-

For priority NDAs, PLAs, ELAs (Establishment Licensing Applications), NDA supplements and PLA and ELA amendments, the “review and act on” period was six months, and this has remained the goal through PDUFA II and PDUFA III. Drugs intended for use against serious and life-threatening illnesses, such as cancer, HIV/AIDS,

-

and Alzheimer’s disease often fall into this priority category, but they must constitute a therapeutic advance to qualify for priority status.

-

In cases where a major amendment to an application is submitted within three months of the anticipated FDA action date, an additional three months would be added to review time. This feature is intended to discourage filing an application for which additional important data are expected during the review period.

-

Overdue applications and submissions were targeted for elimination within an 18 to 24 month period, depending on their nature.

-

FDA agreed to establish a joint agency/industry working group to oversee efforts to improve review times; implement a project management system within twelve months for NDA reviews and within 18 months for PLA/ELA reviews; implement within CBER a performance tracking and monthly monitoring system similar to that in place in CDER; adopt uniform standards for computer-assisted NDAs in FY 1995; and initiate a pilot computer-assisted PLA program in FY 1993. FDA review time is defined by the agency as “the time it takes FDA to review a new drug application” (U.S. Food and Drug Administration). Approval time is defined as “the time from first NDA submission to NDA approval,” and includes FDA review time for the first submission, plus any subsequent time during which a drug sponsor addresses the deficiencies in an NDA and resubmits the application, plus subsequent FDA review time. The median review time in months for priority NDAs fell from 16.3 months in 1993 to 6.2 months by 1997, to 6.1 months by 1999, and 6.0 thereafter (Table 2). Median approval times for priority NDAs fell from 20.5 months in 1993 to 6.4, 6.1, and 6.0 months for those same years.

For standard NDAs, median review time fell from 20.8 months in 1993 to 12.0 months in 1998 and thereafter; median total approval time fell from 26.9 months to 12.0, 13.8, 12.0, and 14.0 months for 1998 through 2001 (U.S. Food and Drug Administration).

Although the trend toward shorter review and approval times had begun before PDUFA—approval times of 30–32 months on average for new molecular entities in the 1970s and 1980s had fallen to 24 months by 1990 (Temple, 1996)—the continued, rapid decline is associated with implementation of PDUFA

Broader Impacts of PDUFA

The intent of PDUFA was to shorten product review and approval times, and times did become shorter. Furthermore, the salience of FDA’s health promotion mission, that of getting good products to market and available to patients quickly, was enhanced relative to its consumer protection mission. The mission statement of FDA that became part of the language of FDAMA incorporated these two objectives, although over time questions have been raised whether the balance should have favored consumer protection to a greater extent or indeed whether “the FDA’s first absolute priority is to protect the public health…” (Fontanarosa et al., 2004).

Table 2. APPROVAL TIMES FOR PRIORITY AND STANDARD NDAs CALENDAR YEARS 1993–2001

|

Calendar Year |

Priority |

Standard |

||||

|

Number Approved |

Median FDA Review Time (months) |

Median Total Approval Time (months) |

Number Approved |

Median FDA Review Time (months) |

Median Total Approval Time (months) |

|

|

1993 |

19 |

16.3 |

20.5 |

51 |

20.8 |

26.9 |

|

1994 |

17 |

15.0 |

15.0 |

45 |

16.8 |

22.1 |

|

1995 |

15 |

6.0 |

6.0 |

67 |

16.2 |

18.7 |

|

1996 |

29 |

7.8 |

7.8 |

102 |

15.1 |

17.8 |

|

1997 |

20 |

6.2 |

6.4 |

101 |

14.7 |

15.0 |

|

1998 |

25 |

6.2 |

6.4 |

65 |

12.0 |

12.0 |

|

1999 |

28 |

6.1 |

6.1 |

55 |

12.0 |

13.8 |

|

2000 |

20 |

6.0 |

6.0 |

78 |

12.0 |

12.0 |

|

2001 |

10 |

6.0 |

6.0 |

56 |

12.0 |

14.0 |

|

SOURCE: FDA/Center for Drug Evaluation and Research Last Updated: January 24, 2002 |

||||||

PDUFA also encouraged FDA relations with industry. With PDUFA came clear guidance from CDER leadership that the agency had an obligation to ensure that no more patients than needed were exposed to unapproved pharmaceuticals, and that working with industry to get clinical trials designed well was part of that obligation. PDUFA, then, encouraged a balancing of consumer protection and public health, on the one hand, and a more cooperative, science-based interaction with industry, on the other.

Special Protocol Assessments

Drug sponsors have complained about the lack of consistency by the FDA in communicating to sponsors about drugs from IND through NDA. For example, sponsors have claimed that studies allowed to proceed under INDs, even after repeated discussions with FDA regulatory staff, would be found inadequate in design or execution (even if done according to plan) when the work was complete and the NDA submitted. This was attributed to changes of personnel, and thus, opinions, over the several years that might elapse in drug development. Even though specifics of these cases have not been documented publicly, Congress recognized this as a potential problem and, in FDAMA {section 119(a)}, required FDA to establish a mechanism for prospective agreement on a

detailed study protocol (or at least particular aspects of it) that would—unless exceptional circumstances arose—form the basis for evaluating a product for approval and give sponsors the confidence to proceed knowing what was expected.

To address this problem, an FDA Guidance document for special protocol assessments was issued in May 2002 (Food and Drug Administration, 2002a). A special protocol assessment review can be requested by a sponsor for three types of studies. Although animal cancinogenicity and final product stability protocols are covered, the type most directly relevant to cancer drugs involves clinical protocols for phase III trials whose data will form the primary basis for an efficacy claim in an original NDA, BLA, or supplement when the trials had been the subject of discussion at an end-of-phase II/pre-phase III meeting with the FDA review division, or, in certain other instances, if the FDA was aware of the developmental context in which a protocol was being reviewed with a sponsor and questions answered.

Sponsors are required to submit their protocols before the anticipated start of the study (FDA recommends at least 90 days), allowing enough time to discuss and resolve issues. In applying for a special protocol assessment, the sponsor must identify the specific issues of concern, such as, sample size, study end points, choice of control group, methods for assessing outcomes, among others, and not simply submit the protocol by itself, since it is these specific issues that will be the focus of FDA’s review and of the written agreement that emerges from the process. Under most circumstances, FDA has 45 days to complete the review.

The product of the review is clear documentation in writing of the areas of agreement and disagreement between the FDA and the sponsor on the key issues. The documentation can be in the form of a letter from FDA and/or the minutes of FDA-sponsor meetings. According to PDUFA: “…having agreed to the design, execution, and analyses proposed in protocol reviews under this process, the Agency will not later alter its perspective on the issues of design, execution, or analyses unless public health concerns unrecognized at the time of the protocol assessment under this process are evident.” Furthermore, “(p)ersonal preferences of new individuals on either team (FDA or sponsor) should not affect any documented special protocol assessment.” (Food and Drug Adminstration, 2002a).

Sponsors have been using the special protocol assessment process and publicizing its successful completion for particular products with some enthusiasm. (See, for example, http://www.exelixis.com/index.asp?secPage=arcrelease&rel=119, Monday, September 15, 2003)

Other Issues and Policies of Special Relevance to Oncology Drugs

Two oncology drug development issues have been of particular concern in the cancer community: the end points that are available for clinical trials, and the testing and approval of combinations of drugs, current and future.

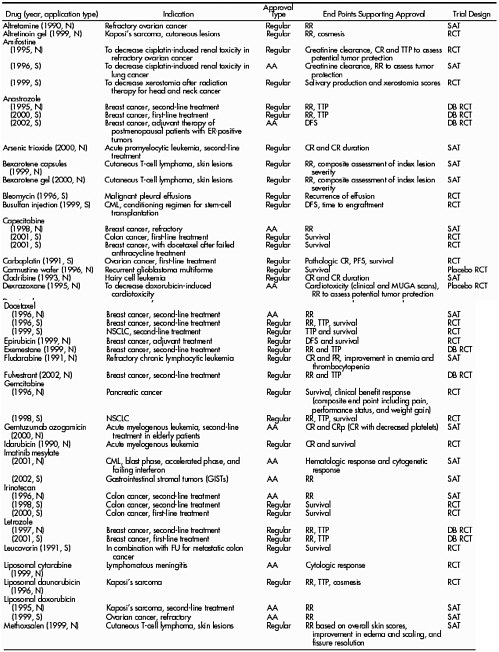

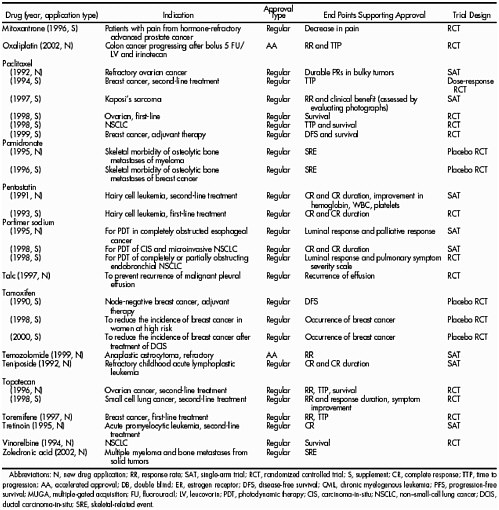

There are no special rules for cancer (or cancer endpoints) in the laws that govern the approval of drugs or biological agents. These agents must meet the same basic evidentiary criteria for safety and efficacy as all other new drugs or biologicals. But the life-threatening nature of the disease and the relative paucity of effective treatments have led to somewhat different benefit-risk ratios for cancer and considerable pressure from drug sponsors and the public to speed approval. For example, between 1990 and 2002, more than half of all anti cancer drug approvals were based on end points short of survival (Johnson et al, 2003). This includes 34 out of 52 traditional approvals for anticancer drugs (including some for more than one indication) (Table 3). Tumor response rate and time-to-tumor-progression (TTP) have been the most commonly relied upon end points, depending on the assumption that improvements in those measurements eventually translate to increased survival times. These issues are discussed below.

Full Approval of Oncology Drugs

Until 1992, drug approval depended on a full, unconditional approval that was based on a direct demonstration of benefit to the patient. In the early 1980s, benefit was defined as either a longer life, a better life, or an established surrogate for one or both of these. Until the mid-1980s, FDA approved cancer drugs on the basis of a better tumor response rate (partial response, the proportion of tumors shrinking by defined degrees; or complete response, the disappearance of the tumor) that was better than the standard treatment. At that time, however, ODAC advised that tumor response was not a validated surrogate endpoint that reliably translated into worthwhile clinical benefit, particularly in light of the toxicity associated with treatment. FDA agreed and began requiring direct evidence of improvement in either survival or symptoms. Since then, FDA has moderated its position, allowing approvals on the basis of impressive improvements in tumor response rates. More recently, disease-free survival (the period between treatment and recurrence) was added to the acceptable end points, particularly for cancers in which most recurrences are symptomatic. The acceptability of a particular end point for full approval is judged on a case-by-case basis, depending on the type of cancer and its natural history and on how convincing the trial results are.

Currently, the end points that may lead to full approval are improved survival (primarily for cytotoxic drugs used as first-line therapy), disease-free survival (applying mainly to adjuvant trials), prolonged time to progression (mainly applied to hormonal or biological products), or palliation of cancer symptoms (usually in conjunction with tumor response). Response rate can be an adequate end point in rare but convincing cases, but it is usually considered as an additional end point, mainly in the case of some hormonal and biological agents. On its own, it can lead to conditional approval (Pazdur, 2000). No drug would be approved if it reduced survival, regardless of other positive effects (Hirschfeld and Pazdur, 2002). In all cases, if there is a standard treatment of demonstrated benefit to patients, the new treatment should be tested against it, to demonstrate either improved efficacy, or equivalent efficacy with a better safety profile. If there is no effective standard treatment, the control can consist of no treatment (usually best supportive care). Because cancer chemotherapy nearly always involves more than one drug, it often happens that a new drug replaces a drug in a known-effective regimen, or is added to a known-effective regimen.

|

|

Clinical trials designed to demonstrate improved survival are usually the most time-consuming and often require the largest numbers of patients. They nearly always require a randomized design, which is also true for trials designed to detect prolonged disease-free survival. Such trials, if large enough and with a long enough period of follow-up, can provide unambiguous evidence of benefit (although toxicities must be taken into account in the analysis). Survival need not be lengthened by years for a drug to be approved on that basis; often weeks or months will do (Justice, 1997).

TTP can serve as an end point if patients have measurable disease when starting to take the drug, and the objective is to inhibit the spread of the disease (measured by imaging studies). Although approvals based on TTP are considered full, not conditional, approvals, they do require the sponsor to follow patients and eventually report survival data. FDA has not approved drugs on the basis of a delay in cancer-related symptoms, but such evidence could fall within the scope of approval for delaying time to progression.

Response rate has figured in the full approvals of biological and hormonal products, including hormonal estrogen-receptor blockers and several aromatase (estrogen production) inhibitors, all for metastatic breast cancer. Complete responses (remissions) of clinically significant duration have been key to approval of other drugs, such as an agent for a rare form of leukemia, which produced complete remissions in the majority of patients (Justice, 1997). In general, the benefits of complete responses in hematological malignancies can be easier to appreciate since they may relieve bleeding or infections or the need for transfusions.

Partial responses (that is, decrease, but not disappearance, of the malignancy) are less likely than complete responses to be associated with an overall patient benefit (taking into account toxicities and the duration of response) and are much less likely to figure in full approvals. Approvals based on response rate generally require evidence of other benefit (such as palliation of symptoms) and require follow-up data to assure that survival has not been compromised.

End points intended as surrogates for survival (recurrence, progression, and response rate) have advantages in generally requiring smaller numbers of participants, regardless of trial design (because the number of definitive end points is larger) and because they can be completed more quickly. They can also be problematic to interpret because of the difficulties of standardizing measurement, because measurements occur at fixed points, and other ambiguities in quantitative determination of tumor size (or other disease measures).

Symptom control is an accepted end point as part of the evaluation for full approval of cancer drugs. Examples include a drug for pain control in men with hormone refractory prostate cancer and other agents for symptom control in small cell lung cancer, myeloma, and breast cancer, among others.

No cancer therapeutics have been approved thus far on the basis of a global quality of life measure, but they could be if the measures met certain criteria (for example, validation in the population and correlation with other disease-specific changes) and the benefit was considered to be of great enough value to patients. In general, for 90 separate claims from 1985 to 2003, approvals have usually been based on multiple end points, with response rate most frequent (60 percent of all claims and 75 percent of accelerated approvals), overall survival in 27 percent of all claims (only 5 percent as a sole end point), and time to tumor progression in 26 percent (Roberts and Hirschfeld, 2005).

Accelerated (Conditional) Approval

In response to pressure generated, as noted earlier, by the life threatening nature of cancer coupled with the paucity of effective treatments for this disease, Congress and the FDA developed measures to respond to the needs of sponsors, providers, and the public through legislation and regulations to allow faster approvals for new cancer drugs for which actual improvements in survival had not yet been shown. This kind of approval is conditional on the sponsor going forward with definitive post-marketing trials to demonstrate clinical benefit.

Preliminary measures to speed access to new drugs (Treatment INDs and parallel track/expanded access) had been tried for AIDS, but in 1992 FDA issued subpart H of its regulations for NDAs (21 CFR 314), a more formal solution that allowed sponsors to apply for accelerated approval for drugs that provide meaningful therapeutic benefit to patients over existing treatments (for example, ability to treat patients unresponsive to, or intolerant of, available therapy, or improved patient response over available therapy). Accelerated (or, as it was first named, conditional) approval may be granted on the basis of a surrogate endpoint(s) likely to predict clinical benefit such as various response rates, but definitive studies are supposed to be completed with due diligence for the approval to become final, assuming clinical benefit is confirmed. According to the preamble to the accelerated approval regulations, confirmatory trials would usually be under way at the time of the accelerated approval, although FDA has not required this, and it has not always been the case. If those trials are not completed or do not confirm a benefit, the FDA may exercise the option of accelerated withdrawal. However, when a confirmatory trial did not confirm a benefit (gefinitib), FDA did not withdraw the drug as noted below.

Between 1992 and 2003, 14 drugs for 19 cancer indications were granted conditional, accelerated approval. In early 2003, FDA and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) reviewed progress in completing the post-marketing, confirmatory trials for all of these drugs with ODAC. In four cases, the confirmatory trials had been completed and had led to full approval. Of the remaining drugs, eight that had received accelerated approval between 1995 and 2000 were reviewed with the following findings: a post-marketing trial was completed but was uninterpretable by FDA; the incidence of the indication being addressed by the drug (Kaposi’s sarcoma in AIDS) had decreased substantially since the original trials, making patient recruitment difficult; the first confirmatory study was inconclusive, and a second was begun; and a number of trials were underway, but not completed. In none of these eight had trials been completed with analyzable data, and in some cases problems with design and patient recruitment remained (Cancer Letter, 2003). By mid 2004, updated figures were reported: only 6 of 23 “oncology related” accelerated approvals had received full approval. The same source also reported, that from the time of the first oncology accelerated approval in 1995, about one third of all cancer drug approvals were accelerated based on surrogate endpoints (Roberts and Chabner, 2004)

One observer has asked “…whether the accelerated approval mechanism enhances or hinders a sponsor’s ability to complete definitive clinical trials with a new agent and, therefore, whether this regulatory strategy is in the best interest of cancer

patients” (Schilsky, 2003). Accelerated approvals may represent real treatment advances, but if studies are not completed, are inconclusive, or do not support the original evidence of efficacy, FDA may have a difficult time deciding on the appropriate action. At the ODAC meeting reviewing accelerated approval post-marketing trials, a senior FDA official commented that when a drug has proved active in a setting where nothing else had worked, it was not likely to be withdrawn because a post-marketing trial failed to show overall survival advantage (Cancer Letter, 2003).

In fact, as of 2005, FDA has never withdrawn a drug for lack of efficacy, only because of safety problems, and safety data available for drugs given accelerated approval have been sparse compared with data from regular approvals. Even after completion of post-marketing trials and full approval, some drugs originally granted accelerated approval had numbers of patients in their safety databases which were significantly smaller than numbers usually available when a cancer drug is granted regular traditional approval18. Those numbers, although probably sufficient to uncover common toxicities, may pose risks of missing rare toxic reactions (Schilsky, 2003). For example, three years following the full approval of one such drug (irinotecan) two large clinical trials were interrupted because of concerns of previously unrecognized thromboembolic toxicity and early death (Sargent et al., 2001). At present, there appears to be no real penalty if confirmatory studies are either not completed or show a lack of benefit, and the record suggests that considerable time may elapse before data are available for a decision in many instances. However, it should be noted that FDA and sponsor agreed to suspend marketing of one drug (gefitinib) in December 2004 when a phase III trial failed to confirm a survival benefit in lung cancer. Subsequently, use of the drug by clinical oncologists plummeted presumably because they were aware of the trial’s results and were no longer prescribing it.

Testing and Approval of Drug Combinations for Cancer

The complexity of cancer has traditionally required the use of combinations of drugs with different mechanisms of action for most successful treatments. Also, the toxicity of most treatments and the ethics of testing against placebo in a potentially fatal disease have resulted in testing protocols that are more comparative with existing therapies than for drugs used in other diseases; therefore approvals are often based on comparatively better results in important health outcomes or lesser toxicity with equivalent survival or both. Treatment with a single conventional chemotherapy agent does not provide a durable cure, and this is likely to be so even for highly-targeted drugs.

The advent of new compounds more precisely targeted to specific molecular abnormalities of cancer cells, where activity against multiple targets may be required for effective results, poses additional new challenges to the drug developer and to regulatory agencies. Although qualitative and quantitative changes in molecular targets may be

|

18 |

In fact, a subsequent review updated (but not significantly) the totals reported here and concluded that 62 percent of accelerated approval indications were based on trials of fewer than 200 patients and that safety data were often incomplete—Veronese, ML. Report card for accelerated FDA approval oncology drugs (1995–2003): is it time for a make-up test?—Accessed, 12/10/04 (and posted June 6, 2004) at http://www.oncolink.upenn.edu/custom_tags/print_article.cfm?Page=2&id+1087&Section=Conferences |

measurable after a single targeted agent is given to patients, actual antitumor effects may not occur with a single agent and only be observed when multiple targets in the cancer pathway are affected by combinations of multiple targeted drugs or of newer targeted drugs with older cellular toxic drugs. And some new compounds may only suppress tumor growth but not necessarily cause tumor regression. When it comes to drug approvals, the end points appropriate for conventional chemotherapy agents may not be the most appropriate for some newer agents used in combination with other approved agents, or in combinations that involve more than one new agent. Research and development and regulatory difficulties posed by combination therapies in cancer are discussed below.

Approval of an Active Experimental Agent in a Combination, Where the other Agent(s) is a Licensed Product

It is not unusual for a new anticancer agent to be approved on the basis of activity in a combination regimen in pivotal trials19 after the activity of the drug as a single agent has previously been demonstrated using the surrogate of tumor regression. A study design of the type A+B vs. A, where A is an approved agent and B is the experimental agent, may isolate the value of B and is therefore frequently used in pivotal trials. Other designs such as A+B versus A+C, where B is the only experimental agent have also been used. For example, in a trial of a new agent for advanced or metastatic non-small cell lung cancer, approval was based on a small survival advantage in an A+B vs A trial and an improved TTP and response rate (but no survival advantage) in the confirmatory A+B vs A+C trial (Eli Lilly and Company, 2003).

The monoclonal antibody targeted against the HER2 receptor in breast cancer was also approved (in February 2000) on the basis of the study design A+B vs. A (Genentech, 2003). In the pivotal trial, patients whose tumors over-expressed the HER2 protein and who had not previously been treated for metastatic disease, were randomized to chemotherapy with or without the new monoclonal antibody. In this case, the primary endpoint of the study was a statistically improved median TTP in the antibody containing arm of the trial. Subsequent data from the trial showed survival benefits.

Approval of Combinations of 2 (or more) Currently Unlicensed Products

Approval of two or more unlicensed products is governed by the general safety and efficacy provisions of the FDCA and FDA regulations. Although the FDA permits use of two or more investigational drugs in trials, the agency requires an evaluation of the effect of each drug individually, separate from the other drugs with which they are used, for approval of both drugs against cancer (Plaister, 2000) or other life threatening diseases (Food and Drug Administration, 2002c). When more than one investigational agent is included in a phase III pivotal trial, FDA recommends that the study design allow the contribution of an investigational agent to be distinguished (for example, through a factorial design). In any event, there are no clear examples in oncology where a

Table 4. Activity of oxaliplatin in combination with 5FU/leucovorin (LV) in colorectal cancer. Modified from (Sanofi-Synthelabo, 2002)

|

|

Oxaliplatin+ 5FU/LV |

5FU/LV |

Oxaliplatin |

|

Number of patients |

152 |

151 |

156 |

|

Response rate % |

9 |

0 |

1 |

|

95% Confidence intervals |

4.6–14.2% |

0–2.4% |

0.2–4.6% |

|

Median TIP (months) |

4.6 |

2.7 |

1.6 |

|

95% Confidence intervals |

4.2–6.1 |

1.8–3.0 |

1.4–2.7 |

|

The P value for the comparison of response rate between the oxaliplatin plus 5FU leucovorin arm compared to the 5FU leucovorin arm was 0.0002. |

|||

combination of two unlicensed products has been approved for use together, although the issue arose for a particular combination in 1999 (Plaister, 2000) in the treatment of colorectal cancer. This controversy prompted congressional review, but subsequent discussions between the FDA and the company are not a matter of public record, and the application was withdrawn.

Approvals for an indication where the agent has no clinical activity in its own right

Despite the statement about the need for a drug to have activity in its own right, an important precedent was set by the approval of oxaliplatin in advanced colorectal cancer in August 2002. The basis for approval was a three-arm randomized trial comparing the drug alone against the drug plus standard therapy against standard therapy alone. An interim analysis of response rate and radiographic time to progression after 450 patients were enrolled in the study (Table 4) demonstrated that the drug had essentially no activity as a single agent in colorectal cancer, but in combination with standard therapy, it clearly enhanced the time to progression and response rate of patients. On this basis approval was granted.

At least two additional examples of compounds without intrinsic antitumor activity that have been combined with other agents have entered phase III trials, but neither turned out to have sufficient activity to warrant an NDA. However, it is reasonable to assume that the pivotal study designs were discussed and agreed with the FDA in advance (Levin et al, 2001, Von Pawel et al., 2000), and senior FDA oncology drug officials have commented publicly that there may be instances in which approval might rest on combination activity of a drug(s) inactive as a single agent(s).

Testing of combinations where both are unlicensed products

There are no regulations that prohibit the simultaneous evaluation of two experimental agents, and FDA is said to encourage such studies, as discussed above.

There are several precedents for such evaluations; for example, a phase I/II clinical trial of antibodies directed against the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor and the epidermal growth factor receptor (Mininberg et al., 2003). However, in practice, if two different sponsors are collaborating on such studies, there are likely to be a number of problems.

From a sponsor’s regulatory compliance perspective these problems might include who is responsible for reporting of serious adverse events and other obligations associated with maintenance of the IND. Moreover, non-regulatory issues represent greater barriers to testing of new unlicensed combinations. These include concerns about intellectual property, costs, drug supply, and unanticipated adverse events. In addition, individual companies run clinical trials under a series of company-specific standard operating procedures (SOPs). Their databases are also likely to be incompatible. Agreeing on mutually acceptable SOPs and database access represent large problems for companies and should not be underestimated. In the example cited above, both compounds had the same sponsor. The paucity of other examples suggests that the barriers described above represent substantial hurdles to the simultaneous development of unlicensed agents with different sponsors.

Beyond Current Combinations

Unfortunately, there are few examples where the growth of a cancer cell is dependent on a single specific molecular rearrangement, and therefore the opportunities for specific and selective pharmacological intervention are limited. Although one therapy, imatinib (Gleevec®), has very successfully exploited the 9:22 chromosomal translocation (the Philadelphia chromosome) that occurs in a high proportion of patients with chronic myelogenous leukemia (Druker et al., 2001), in most cases there is substantial redundancy in biochemical pathways within the cancer cell so that pharmacological intervention in one pathway is compensated through other pathways or redundancy in that pathway (Petricoin et al., 2004).

Differences among cancer patients and different cancers in responsiveness and sensitivity to anticancer drugs pose additional problems. If patient populations and particular cancers more likely to respond to therapy and less likely to experience toxicity could be selected by prospective molecular profiling, this would represent a considerable advance in treatment. Pharmacodynamic studies are still in their infancy, but already significant difficulties have been identified including: choice of appropriate molecular endpoints and correlation of target effects with clinical benefits/clinical trial designs and availability of clinical material for testing; assay selection and technical/quality assurance; and ethics, logistical issues, and regulatory considerations, among others.

In May 2002, the FDA and the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA) jointly sponsored a workshop on pharmacogenetics in drug development and regulatory decision-making (Food and Drug Administration, 2002b). In March 2005, the FDA’s policies on phamacogenomic data submissions by industry and on differentiating valid biomarkers and less well developed tests that are observational or exploratory were described in a guidance document intended to progress movement

toward individualized therapy.20 Some of the potential regulatory implications of individualized therapy are illustrated by the following.

If a clinical trial assessed tumor expression of proteins 1 to 10, a reasonable strategy would be to treat each patient with drugs corresponding to those molecular targets aberrantly expressed by that patient’s tumor. One patient might get two drugs and another might get seven drugs, and the two combinations might not overlap. This strategy might be in addition to, or compared against, standard therapy. In any case, decisions would be needed regarding which of all the drugs to consider for approval, or whether to treat them as fixed combinations for defined populations, how to identify appropriate molecularly categorized controls and to randomize, how to handle those drugs that have not been tested for, or found to show, individual anticancer activity; how to assess tumor growth suppression versus regression; among many others.

These are problems and questions that, given the current progress of cancer science, appear possible near-term challenges for both sponsors and regulators, although comments by FDA officials in various forums indicate that the agency understands and is prepared to think constructively about these issues. The FDA’s approval of oxaliplatin also bodes well for its general flexibility in the future, but further thought on its position on the requirement for a drug to have activity in its own right and further careful identification and exploration of the kinds of issues discussed above, are going to be needed. Leveraging the resources of the NCI and FDA, through cooperation and coordination in such identification and exploration of issues (among others), appeared to the agencies to be a sensible approach and is described below through both informal and formal agreements.

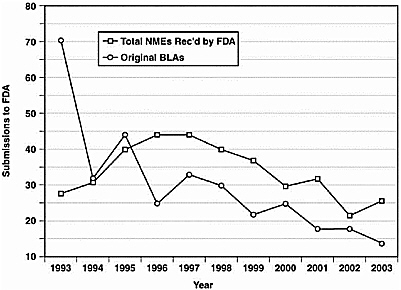

The Critical Path Initiative

Most recently, the FDA has expressed a concern about the gap between the promise of new basic science in general and the development and use at the bedside of new priority drugs of all kinds (see Figure 1). In an attempt to improve evaluation of medical products and the speed and efficiency of review of new drugs, biologics, and devices, and at the same time strengthen evaluation of safety and effectiveness, the agency announced the Critical Path Initiative (Department of Health and Human Services, 2004). This initiative focuses on the critical path from discovery to medical product development to introduction through better safety assessment and evaluation of medical utility (effectiveness), and product industrialization. In collaboration with other agencies, industry and academia, the initiative addresses better evaluative (as opposed to basic or translational) science to develop the tool kit for evaluation of products and faster, less costly, and more predictable approvals. Extensive input was solicited in 2004 from interested parties and the public and a Critical Path Opportunities List is being developed with challenges and opportunities such as biomarkers, improved clinical trials, molecular imaging, data mining from FDA experience, and other possible science and technology

|

20 |

Guidance for Industry Pharmacogenomic Data Submissions http://www.fda.gov/cder/guidance/6400fnl.pdf |

Figure 1. 10-year Trend in New Molecular Entity Drug and New Biological Product Submissions to FDA

that would help FDA and sponsors to move the evaluation process along in a more predictable and efficient way. Along these lines, FDA is considering adding an “exploratory” IND which would allow “phase 0” studies of a group of agents to look at proof of mechanism, receptor occupancy, early pharmacokinetics, and simplified procedures for screening in humans under limited circumstances at limited dosage before, but leading to, the usual investigator IND and phases I through III studies.21 In this way, perhaps, agents more likely to succeed would enter the traditional development process making it less costly and more efficient. While not specific to cancer drugs, this initiative could improve their development and launch as well as drugs for other conditions although it is too early to know how successful it will be. As noted below, NCI has been supportive of the Initiative through the task force described next.

FDA and NCI Initiatives to Enhance Cancer Drug Development and Approval—The FDA/NCI Oncology Task Force

In May 2003, the Commissioner of the FDA and the NCI Director established the joint FDA/NCI Oncology Task Force “to enhance the efficiency of clinical research and the scientific evaluation of new cancer medications” (Barker, July 10, 2003 testimony http://www3.cancer.gov/legis/testimony/barker.html) and “to improve the development and availability of innovative medical products” (Mullin, July 10, 2003 testimony http://energycommerce.house.gov/108/Hearings/07102003hearing990/Mullinl578.htm). The Task Force adds another, more comprehensive, formal interagency agreement to those already in place (for example., the Cooperative Center for Biologics Evaluation and Review-NCI Microarray Program for the Quality Assurance of Cancer Therapies and

other Biological Products, and the FDA-NCI Clinical Proteomics Program), that are focused on specific programs. The new Task Force has a very broad agenda and, as noted above, could help in the ongoing development of new standards for FDA oncology drug review and approval as practice and science evolve.

This collaboration will provide FDA with exposure to state-of-the-art technology that will enable a better understanding of new products in development. NCI will benefit from hands-on experience with FDA’s review process that should help guide research toward faster development of approvable products. Potential areas of collaboration include: joint training and fellowships; developing markers of clinical benefit, including surrogate endpoints; information technology infrastructure to better collect and share data; and ways to improve the drug development process. The first two initiatives announced in November 2003 are a joint cancer fellowship training program and the establishment of an electronic system to link and share data among cancer researchers from throughout the world. (Pam Holland-Moritz, Bioscience Technology, 1/5/04, http://www.biosciencetechnology.com/ShowPR.aspx?PUBCODE=090&ACCT=9000000100&ISSUE=0401&RELTYPE=RLSN&PRODCODE=00000000&PRODLETT=A).

The NCI-FDA Research and Regulatory Review Fellowship program is intended to give scientists interdisciplinary training to enhance proficiency in clinical research, regulatory approval processes, and the ability to translate clinical data into practical patient applications over a one to four year period. Fellows in the program at the M.D., Ph.D., or M.D./Ph.D. level train in clinical oncology programs at NCI and work in regulatory and review programs at the FDA. A primary goal of the collaboration is to provide cross-fertilization between the two agencies. This nationwide fellowship program accepts doctorate level fellows up to and including physicians who have completed their training and are board certified in medical oncology.

The plan to link cancer researchers to the FDA is intended to reduce the time needed to get new drugs reviewed for testing in clinical trials. It includes an electronic system for submitting INDs, created as part of the Cancer Biomedical Informatics Grid (caBIG) project. Uses of databases created through caBIG are expected to assist in dispersing and transferring basic oncology research and clinical trials information to cancer centers.

With NCI involvement, FDA has worked with the American Society of Clinical Oncology to identify biomarkers of clinical benefit as appropriate end points for cancer clinical trials by type of cancer and stage of disease. End points identified through this process will be published in FDA guidance documents. The Task Force may continue this work to identify clinically valid surrogate end points.

NCI and FDA will continue the current collaboration involving proteomics, that is, the discovery of protein markers in the blood that can be used to detect and monitor the progress of disease and drug response, and will also continue the Microarray Program for the Quality Assurance of Cancer Therapies, a program that has provided a foundation for the identification of new molecular targets, understanding of the mechanism of action

of targeted cancer therapeutics, and characterization of complex therapeutic cancer vaccines.

The Task Force plans to address the cancer bioinformatics infrastructure to streamline data collection, integration, and analysis for preclinical, pre-approval, and post-approval research across all of the sectors involved in the development and delivery of cancer therapies. The objective is to reduce the reporting burden for clinical investigators and improve the quality of reported data. Proposals under consideration include: creation of a shared repository for clinical investigator Curricula Vitae (CVs) to keep current and to eliminate the requirement of repeated submissions of such CVs; development of templates for INDs and clinical trial protocols to simplify the process of creating and submitting these documents and improve the quality of submissions. NCI grantees may also be product sponsors that FDA regulates. Given this dual role, there may be duplicative reporting requirements that can be streamlined through this collaborative effort.

Many of these collaborative efforts of the NCI and FDA also relate to the Critical Path Initiative such as a most recent gathering of industry, academia, advocates, and the two agencies to comprehensively review strategies to integrate biomarkers into clinical cancer trials. Also a subgroup of the Task Force is working on the development of biomarkers in coordination with the FDA’s Critical Path Initiative, and a new subcommittee has been formed to examine the use of biomarkers to determine efficacy and long-term toxicity of agents in prevention trials (National Cancer Institute, 2005).

The New FDA Initiative to Speed Approvals

In early 2003, as part of the implementation of PDUFA III, the FDA announced an initiative to examine in three key areas the causes of delays in product approvals and find ways for the agency to reduce them (U.S. Food and Drug Administration). Two areas are of particular importance to cancer products: multiple review cycles for NDAs before they are approved; and guidance for preclinical and clinical product development, “to reduce uncertainty and increase efficiency for innovator product development.” The third area, of general relevance to all types of products, is the institution of a continuous improvement/quality systems approach throughout premarket review.

Even though FDA is generally meeting its targets of 10 months for standard NDA reviews and six months for priority reviews, total approval times are often longer because NDAs fail to gain approval in a single cycle. CDER analyzed FDA experience with long review times for new molecular entity NDAs that were approved from January 2000 through either August 2001 (for priority reviews) or December 2001 (for standard reviews). Of approximately 30 NMEs undergoing standard review, 57 percent took longer than 12 months to be approved, ranging up to 54 months, and were almost evenly split between two and three review cycles. Approximately 15 NMEs had priority reviews, and 48 percent were approved in six months or less in one review cycle. Just less than half (46 percent) were approved in two cycles, and the rest were mostly approved in two cycles, although some took three cycles, the longest 54 months.

Failure to demonstrate safety (38 percent), concerns about efficacy (21 percent), manufacturing and labeling issues (14 percent each), chemistry, manufacturing and controls (10 percent) and general quality (3 percent) were the causes of prolonged standard reviews. Chemistry, manufacturing, and controls issues (46 percent), followed by safety (27 percent), efficacy (18 percent), and manufacturing (9 percent) made up the causes for prolonged priority reviews. A similar, but less comprehensive, study of biologics products by CBER found that the primary reasons for delayed approval related to major changes in product manufacturing (7 of 11 BLAs), and the rest related to efficacy and safety. Although analyses involved relatively small numbers of products, they appeared to rule out FDA procedures as the cause of delay. However, they suggested to the FDA that problems could be reduced through clearer guidance and improved communication to sponsors.

Guidance documents represent an important FDA communication device to companies and other sponsors. Under the new FDA initiative to speed approvals, the Center for Oncology Drug Products is undertaking to produce better guidance for oncology products on key topics and has been in discussion with the American Society of Clinical Oncology about appropriate endpoints for cancer clinical trials, as well as developing other documents within the agency.

Several hundred current FDA guidance documents address a wide range of topics, including several dozen related to cancer. Guidance documents do not have the force of law or regulation, nor do they legally bind FDA or drug sponsors. But they do communicate the agency’s current thinking on a subject, and FDA employees are generally expected to adhere to them. FDA defines guidance documents as those prepared for FDA staff, applicants/sponsors, and the public that describe the agency interpretation of, or policy on, regulatory issues such as design, production, labeling, promotion, manufacturing, and testing of regulated products; the processing, content, and evaluation or approval of submissions; and inspection and enforcement (21 CFR 10.115).

Procedures for developing guidance documents had been reviewed and amended in provisions of FDAMA and more formally described in an updated regulation (21 CFR 10.115), effective October 2000. The regulation created two categories of guidance. Level 1 guidance documents are for new or changed interpretations of statutes or regulations and for more complex or controversial issues. They follow a notice and comment procedure, with initial publication of a draft on the Internet, followed by preparation of a final version for Internet availability. A notice in the Federal Register announces the document. This process can involve more than one round of review and comment and may take years for controversial subject matter. Level 2 documents explain existing practices or minor changes in interpretation and are prepared by FDA, with input and involvement from inside and outside FDA, as deemed appropriate. They are then posted on the Internet and implemented immediately.

Guidance documents are of great importance because FDA staff are restricted in ways they can convey this kind of information to their constituencies. According to 21 CFR 10.115, “The agency may not use documents or other means of communication that are excluded from the definition of guidance document to informally communicate new

or different regulatory expectations to a broad public audience for the first time.” In meetings with drug sponsors about specific products, FDA staff may discuss regulatory requirements, but guidance documents are otherwise the main sources of information.

Summary of the FDA Role

The FDA strongly influences drug development and marketing, mostly toward the end of the process. Drug discovery, early development and some preclinical work is largely unaffected by the legal requirements that FDA enforces, and is much more dependent on decisions taken by drug developers and the state-of-the-art of cancer science. The FDA’s influence becomes increasingly critical as information is developed specifically for an IND submission and is felt most during the period of clinical studies and the preparation of an NDA or BLA.

The means available to FDA to allow the drug development and approval process to proceed efficiently involve streamlining internal procedures and making sure that sponsors are able to streamline their research and development to produce what is needed in a form that meets the evidentiary standards of the laws and regulations that FDA is charged with carrying out. Changing the standards themselves is a Congressional prerogative. The Congress has kept a close watch on the FDA, and has enacted legislation (for example, through FDAMA and PDUFA, as mentioned several times in this chapter) facilitating accelerated approval, expedited reviews, and other innovations that have allowed the agency to speed the drug development and approval process. FDA itself has taken steps to improve reviews and approvals and implement cancer specific changes, such as moving toward providing a single cancer focus in the agency.