1

INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND

The Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (frequently referred to as the WIC program) is one of the largest food assistance programs in the United States. In terms of dollars or in terms of number or participants, the WIC program is exceeded only by the food stamp and school nutrition programs (FY2003 data; FNS, 2004a, 2004b, 2004f). Created as a pilot program in 1972 and permanently established in 1974, the WIC program has provided nutritious food, valuable nutrition education, breastfeeding support, and important health and social service referrals to millions of families over the past 30 years. Approximately one-half of all infants in the United States (54.2 percent in 2000) and one-fourth of children ages 1 through 4 years1 (25.4 percent in 2000), along with many of their mothers, receive supplemental nutrition through the WIC program (Bartlett et al., 2002; U.S. Census Bureau, 2001).2 The WIC program is an investment in the nutrition of the people of the

United States during the earliest stages of life and thus has the potential to promote both the short- and long-term health of the nation.

In 1974, Congress authorized $100 million for the WIC program for fiscal year 1975 (U.S. Congress, Pub. L. No. 93-326, 1974); by the end of June 1975, more than 200,000 women, infants, and children were participating in the program. From the start, the WIC program has worked to improve the nutrition of eligible low-income pregnant, postpartum, and breastfeeding women;3 infants;4 and children.5 The WIC program does this by providing four main benefits: (1) supplemental food; (2) nutrition education; (3) breastfeeding support; and (4) referrals to health and social services. About three-fourths of funds for the WIC program are used to provide the food packages.

Unlike other federal food assistance programs, WIC is a highly targeted nutrition program. It aims “to provide supplemental nutritious food as an adjunct to good health care during such critical times of growth and development … to prevent the occurrence of health problems” (U.S. Congress, Pub. L. No. 94-105, 1975) and “improve the health status of these persons” (U.S. Congress, Pub. L. No. 95-627, 1978). In fiscal year 2003, the WIC program served an average of 7.6 million women, infants, and children per month at a total yearly cost of $4.5 billion (FNS, 2004f). The cost for the supplemental food that year was $3.2 billion (FNS, 2004f). However, WIC is not an entitlement program; the numbers of eligible women, infants, and children who can be served by the WIC program may be limited by the amount of funds appropriated to the program. To meet the WIC program’s goals of disease prevention and health promotion most effectively, the supplemental foods provided in the food packages must help address current nutritional concerns for participant groups while controlling costs. Thus, the food packages should be designed to improve participants’ food and nutrient intake to promote improved health.

Throughout the 30 years of the WIC program, many changes have occurred in the demographics and health risks of the population served, in

the food supply and dietary patterns, and in dietary guidance. Many groups and individuals have called for changes in the supplemental foods provided by the WIC program. Researchers have documented reasons for change; however, the only notable change made in the supplemental foods provided occurred in 1992, when the set of foods provided for breastfeeding women was somewhat expanded.

THE COMMITTEE’S TASK

In response to many concerns about the WIC food packages, the Food and Nutrition Service of the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) asked the Institute of Medicine (IOM) to conduct a review of the WIC food packages. The Food and Nutrition Board undertook the project in September 2003, and the committee to Review the WIC food packages was appointed to conduct the study. The committee’s task follows.

The committee’s focus is the population served by the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (the WIC program). Specific tasks for the committee during Phase I were to review nutritional needs, using scientific data summarized in Dietary Reference Intake reports (IOM, 1997, 1998, 2000b, 2001, 2002/2005, 2005a); assess supplemental nutrition needs by comparing nutritional needs to recent dietary intake data for pertinent populations; and propose priority nutrients and general nutrition recommendations for the WIC food packages. The publication, Proposed Criteria for Selecting the WIC Food Packages: A Preliminary Report of the Committee to Review the WIC Food Packages (released in August 2004), presented the committee’s findings for Phase I of the project (IOM, 2004b). The Phase II task is to recommend specific changes to the WIC food packages. Recommendations are to be cost-neutral, efficient for nationwide distribution and vendor checkout, non-burdensome to administration, and culturally suitable. The committee will also consider the supplemental nature of the WIC program, burdens and incentives for eligible families, and the role of WIC food packages in reinforcing nutrition education, breastfeeding, and chronic disease prevention.

Responding to the request from the Food and Nutrition Service, this report presents evidence of the need for change and analyses of the types and amounts of current and proposed foods in the WIC food packages. Based on these analyses, the report provides detailed recommendations for the supplemental foods to be offered for each category of WIC participants. This chapter incorporates data from the Phase I report to provide an overview of the WIC supplemental nutrition program, a review of reasons why a systematic evaluation and revision of the supplemental food benefit is timely, a summary of the criteria the committee proposed for designing new WIC food packages, and the basis for the criteria.

THE SPECIAL SUPPLEMENTAL NUTRITION PROGRAM FOR WOMEN, INFANTS, AND CHILDREN

The WIC program is a federal grant program to 50 states, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, Guam, American Samoa, the American Virgin Islands, and 34 Indian Tribal Organizations (Kresge, 2003). For convenience, the terms state agency or WIC state agency are used to refer to the entities administering the WIC program in these 89 locations. Working within federal regulations, the WIC state agencies oversee the targeted food assistance, nutrition education, breastfeeding support, and health and social service referral program for eligible women, infants, and children. Eligibility for the WIC program requires meeting all three of the following requirements:

-

Categorical Eligibility—being a member of one of these groups: pregnant woman; breastfeeding woman up to 1 year postpartum; woman less than 6 months postpartum; infant age 0 through 11 months; or young child from age 1 through 4 years;

-

Income Eligibility—living in a family with any of the following characteristics—income at or below 185 percent of federal poverty guidelines or enrolled in Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, Food Stamp, or Medicaid programs (or other assistance program designated by the state of residence); and

-

Nutritional Risk—having at least one of an approved list of nutritional risk factors for a poor health outcome. Examples of nutritional risk include specific criteria for anemia, obesity, and underweight.

Those enrolled and participating in the WIC program (or their caregivers) receive the following: (1) supplemental food; (2) nutrition education; (3) breastfeeding support; and (4) referrals to health and social services, as applicable. Ideally, the supplemental food and nutrition education components complement each other. By law (U.S. Congress, Pub. L. No. 101-445, 1990), the Dietary Guidelines for Americans form the basis of federal food, nutrition education, and information programs. This means that both the food and nutrition education provided by the WIC program should be consistent with the Dietary Guidelines (see section on Nutrient Recommendations and Dietary Guidance Have Changed and Chapter 2—Nutrient and Food Priorities—for more information).

Supplemental Foods and Target Nutrients

The definition of WIC supplemental foods found in the statutes has evolved (see Appendix F—Supplementary Information—Box F-1 for de-

tailed information). The most recent definition, “those foods containing nutrients determined by nutritional research to be lacking in the diets of pregnant, breastfeeding, and postpartum women, infants, and children, and those foods that promote the health of the population served by the program authorized by this section, as indicated by relevant nutrition science, public health concerns, and cultural eating patterns …”, provides considerable latitude for USDA to name the foods to be included. Congress no longer names target nutrients, as it did in the original WIC statute (U.S. Congress, Pub. L. No. 92-433, 1972), an amendment to the National School Lunch Act. Instead, the current law calls for the use of nutrition research to identify key nutrients and evidence concerning the nutrient content of foods, public health problems, and eating patterns to identify appropriate foods.

The term target nutrients has remained in use despite its being dropped from the statutes in 1978. A WIC Food Package Advisory Panel, convened in 1978, recommended retaining calcium, iron, vitamin A, vitamin C, and high-quality protein as the target nutrients. Investigators at Pennsylvania State University (Guthrie et al., 1991) submitted to USDA technical papers that addressed current and new target nutrients. In 1992, the National Advisory Council on Maternal, Infant, and Fetal Nutrition used those papers and other materials to develop recommendations to Congress and the President (NACMIFN, 1991). Their report recommended that folate, vitamin B6, and zinc be added as target nutrients, but this recommendation did not result in changes in the statutes or regulations. In 2003, the USDA published a request for public comments regarding revisions to the WIC food packages (FNS, 2003a). Under a contract from the USDA, the IOM formed the Committee to Review the WIC Food Packages. As stated under The Committee’s Task above, the Food and Nutrition Service asked the IOM committee to identify priority nutrients based on current scientific evidence. In accordance with current scientific evidence and dietary guidance, the committee identified both priority nutrients and priority food groups for the WIC food packages with regard to both inadequate intakes and excessive intakes.

The WIC Food Packages

When the WIC program first began serving mothers, infants, and children, USDA devised market baskets of food that could be made available to recipients in amounts not to exceed defined maximum quantities. Later these “market baskets” came to be called WIC food packages. Table 1-1 identifies the maximum contents of the current WIC food packages. The number of food packages (seven) exceeds the number of participant categories (five) to take into account the changing needs of infants (Food Packages

TABLE 1-1 Current WIC Food Packages, Maximum Monthly Allowances

|

Foods/Package |

Formula-Fed Infants, 0–3.9 mo |

Formula-Fed Infants, 4–11.9 mo |

Children and Women with Special Dietary Needs |

|

Number |

I |

II |

III |

|

Infant formula (concentrated liquid)c |

403 fl oz |

403 fl oz |

403 fl ozd |

|

Juice (reconstituted frozen)e |

|

96 fl ozf |

144 fl oz |

|

Infant cereal |

|

24 oz |

|

|

Cereal (hot or cold) |

|

|

36 oz |

|

Milkg |

|

|

24 qt |

|

Cheeseg |

|

|

|

|

Eggsh |

|

|

|

|

Dried beans or peas and/or Peanut butter |

|

|

|

|

Tuna (canned) |

|

|

|

|

Carrots (fresh)i |

|

|

|

|

aIn addition to pregnant women, breastfeeding women whose infants receive formula from the WIC program may receive Food Package V. bFood Package VII is available to breastfeeding women who do not receive infant formula from the WIC program. cPowdered or ready-to-feed formula may be substituted at the following rates: 8 lb powdered per 403 fl oz concentrated liquid; or 26 fl oz ready-to-feed per 13 fl oz concentrated liquid. dMay be special formulas or medical formulas, not just infant formula; additional amounts of formula may be approved for nutritional need, up to 52 fl oz concentrated liquid, 1 lb powdered, or 104 fl oz ready-to-feed. eSingle strength adult juice may be substituted at a rate of 92 fl oz per 96 fl oz reconstituted frozen. |

|||

|

Children, 1–4.9 y |

Pregnant or Partially Breastfeeding Women (up to 1 y postpartum)a |

Non-Breastfeeding Postpartum Women (up to 6 mo postpartum) |

Breastfeeding Women Enhanced Package (up to 1 y postpartum)b |

|

IV |

V |

VI |

VII |

|

288 fl oz |

288 fl oz |

192 fl |

oz 336 fl oz |

|

36 oz |

36 oz |

36 oz |

36 oz |

|

28 qt |

24 qt |

28 qt |

|

|

|

|

|

1 lb |

|

2–2.5 doz |

2–2.5 doz |

2–2.5 doz |

2–2.5 doz |

|

1 lb or 18 oz |

1 lb or 18 oz |

|

1 lb and 18 oz |

|

|

|

|

26 oz |

|

|

|

|

2 lb |

|

fInfant juice may be substituted for adult juice at the rate of 63 fl oz per 92 fl oz single strength adult juice. gA choice of various forms of milks and cheeses may be available. Cheese may be substituted for fluid whole milk at the rate of 1 lb cheese per 3 qt milk, with a 4-lb maximum. Additional cheese may be issued in cases of lactose intolerance. hDried egg mix may be substituted at the rate of 1.5 lb per 2 doz fresh eggs; or 2 lb per 2.5 doz fresh eggs. iFrozen carrots may be substituted at the rate of 1 lb frozen per 1 lb fresh; or canned carrots at the rate of 16–20 oz canned per 1 lb fresh. DATA SOURCE: Adapted from http://www.fns.usda.gov/wic/benefitsandservices/foodpkgtable.htm (FNS, 2004e). |

|||

I and II in Table 1-1) and the special dietary needs6 of a small group of children and women (Food Package III).

The Food and Nutrition Service has set nutritional standards for some of the food items allowed in the WIC food packages. By regulation, for example, juice products must be 100 percent fruit or vegetable juice and must contain a minimum amount of vitamin C per unit volume; breakfast cereals must provide a minimum amount of iron but not more than a specified amount of sugar per unit weight.

While meeting federal specifications, each WIC state agency determines which forms or brands of foods are allowable. Tailoring of food packages at the local level with regard to the specific nutritional needs of an individual may involve decreasing the amount of a food item below the maximum allowance at the federal level. WIC state agencies also have some flexibility, on a case by case basis, to substitute more culturally appropriate foods if they are nutritionally equivalent and cost-neutral. Such substitutions must be approved at the federal level. Only 3 of 10 petitions for substitutions based on cultural preferences have been allowed since 1990 (personal communication, Tracy Von Ins, Office of Analysis, Nutrition and Evaluation, Food and Nutrition Service, FNS, USDA, 2004).

Each WIC state agency develops a food list. In doing so, the state agency determines whether it will use the minimum federal nutritional standards for specific foods or set higher nutritional standards, the types of foods that will be allowed (e.g., fresh, frozen, or canned carrots for breastfeeding women), and the brands that will be allowed, when applicable. WIC state agencies have the option of approving products such as calcium-fortified juice for inclusion on their lists of WIC-approved juices. The Food and Nutrition Service encourages state agencies to develop policies and procedures for local agencies to follow when prescribing such foods (FNS, 2004d). To help control costs, WIC state agencies negotiate with infant formula companies and select a sole provider. In exchange for allowing the single brand of formula, the formula company provides the state agency with a substantial rebate for formula provided to WIC participants.

At the local level, a Competent Professional Authority7 (CPA) assesses each participant’s nutritional needs and food preferences and prescribes a

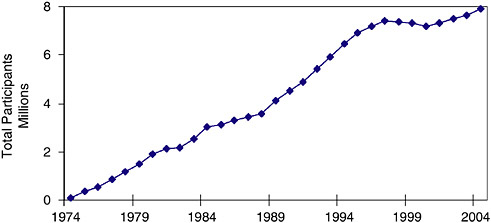

FIGURE 1-1 Annual number of participants in the WIC Program constructed from monthly averages of participants, fiscal years 1974–2004.

DATA SOURCE: USDA website (FNS, 2004f, 2004g). Data from FY 2003 (12 months) are the latest complete data set. Data for FY 2004 (preliminary data) are incomplete.

tailored food package—one that fits the participant’s needs and circumstances to the extent that the amounts and WIC-approved foods allow. Most local WIC clinics do not actually distribute the food packages. Instead, a WIC staff member provides the participant or his or her caregiver with a food instrument (usually either an itemized voucher or check) that can be exchanged for specific foods in participating grocery outlets.8 Examples of choices include the kind of fruit juice and the fat content of the milk. The food instrument lists the quantities of specific food items, sometimes including brand names, that may be obtained.

WHY CONSIDER CHANGES IN THE WIC FOOD PACKAGES?

Marked Demographic Changes Have Occurred in the WIC Population

Over the past several decades, the total number of persons served by the WIC program has increased greatly (see Figure 1-1), and the demo-

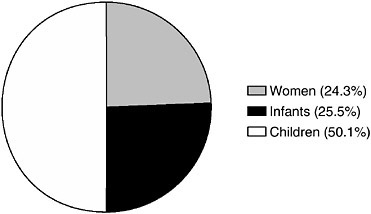

FIGURE 1-2 The WIC population by participant category, 2003.

DATA SOURCE: USDA website (FNS, 2004f ). Data from FY 2003 are the latest complete data set.

graphics of the WIC population have changed greatly as well. In fiscal year 1974, the year when WIC became a permanent program, WIC served an average of 88,000 women, infants, and children per month. In sharp contrast, during 2003, the WIC program served an average of 7.6 million women, infants, and children per month at a cost of $4.5 billion for the fiscal year (FNS, 2004f). The distribution of the WIC caseload is approximately 50 percent children, 25 percent infants, and 25 percent women (Figure 1-2, data for 2002) (Cole et al., 2001; FNS, 2004f).9

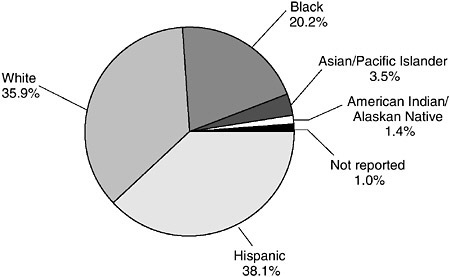

The ethnic composition of the WIC population has shifted substantially. Hispanics constituted 38 percent of the WIC caseload in 2002, up from 21 percent in 1988. Asians and Pacific Islanders have become a substantial part of the WIC population in several states over the same period. Figure 1-3 illustrates the ethnic and racial diversity of the WIC population in 2002. The diversity of the WIC population actually is greater than Figure 1-3 suggests, since each of these major racial/ethnic groups is composed of numerous subgroups. For example, people with a cultural heritage from anywhere in Mexico, Central America, South America, the Caribbean, or Spain may self-identify as being of Hispanic origin. Ethnic composition varies among geographic areas, even within states, with some local WIC clinics serving much more ethnically diverse populations than others.

FIGURE 1-3 Ethnic composition of the WIC population, 2002 (percentage). DATA SOURCE: WIC Participant and Program Characteristics 2002 (Bartlett et al., 2003).

A growing proportion of women who participate in the WIC program are in the work force. In a study reported in 1988, 14.5 percent of pregnant women enrolled in the WIC program were employed (Rush et al., 1988a). In 1998, about 25 percent of the women who were certified for the WIC program or who certified a child were employed (Cole et al., 2001). This is consistent with data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics showing that work activity has increased recently in low-income households with children (Federal Interagency Forum on Child and Family Statistics, 2001), although other factors may have affected these statistics for the WIC program. Among children who lived with both parents in families with income below the poverty level, the proportion with at least one parent employed full-time increased from 44 percent in 1990 to 52 percent in 1999 (GAO, 2001). Over the same period, the proportion of poor children living in families with a single mother employed full-time doubled, from 9 to 18 percent.

The Food Supply and Dietary Patterns Have Changed

Increased Variety in the Food Supply

The number of food products in U.S. retail food outlets has increased approximately 60 percent since 1990. Between 1997 and 2003, an average

of 10,539 new food products were introduced into the market each year (Food Institute, 2002, 2003, 2004a). Many of these were existing products that were repackaged or relabeled, or they were simple line extensions. Recent new food products include consistent-weight packages of fresh fruits and vegetables that were formerly purchased as bulk, random-weight items. Each product is called a stock-keeping unit (SKU) by food manufacturers and vendors. The average number of SKUs in a typical supermarket has increased from 20,000 items in 1990 to over 32,000 items in 2002 (Food Institute, 2002).

A wider variety of fresh produce is now available year-round at reasonable prices and in many more locations. Variety in the forms of food products also has increased. For example, more foods are fortified with particular nutrients. Examples include oatmeal fortified with iron and orange juice fortified with calcium and vitamin D. More brands of products are available. Supermarkets are differentiating themselves from competition and building store loyalty through expansion of their own “store brands.” In a typical supermarket, the percentage of SKUs that are store-brand products rose from 18.6 percent in 1995 to 20.7 percent in 2004 (Food Institute, 2004a). The baby food category experienced the greatest increase in private-label brands in 2003 (Food Institute, 2004b). Most store-brand products are priced between 15 and 50 percent lower than national-brand products of similar quality (Food Institute, 2002).

Changes in Food Consumption

The percentage of personal disposable income spent for food from retail stores has fallen over the last several decades. The average American household spent 7.8 percent of disposable income on food eaten at home in 2001(BLS, 2003), compared to over 10 percent in 1970 (ERS, 2004a). Despite this trend, households in the lowest income quintile, which would include most WIC participant households, spend 25 percent of their disposable income for food at home (Blisard, 2001). Table 1-2 shows trends and changes in women’s consumption of selected types of food between 1977 and 1995. The trends in mean dietary intakes for women 20 years of age and older reveal substantial increases in beverages (a 114 percent increase for carbonated beverages), grain products (a 44 percent increase), and sugars and sweets (a 22 percent increase) (Enns et al., 1997). Mean intake of eggs decreased by 33 percent (Enns et al., 1997). Similar trend data were available for children ages 6 through 11 years (Enns et al., 2002), but no trend data of this type were available for children in the age range eligible for the WIC program.

TABLE 1-2 Trends and Changes in the Consumption from Selected Types of Food: Mean Intakes for Women 20 Years and Older

The Health Risks of the WIC-Eligible Population Have Changed

Since the inception of the WIC program, fundamental changes have occurred in the major health and nutrition risks faced by the WIC-eligible population. The prevalences of underweight (Sherry et al., 2004) and of iron-deficiency anemia (Sherry et al., 1997, 2001) have decreased. Diets have improved in many respects, and nutrients for which intakes often appeared to be low in the 1970s (calcium and vitamins A and C) are less problematic, particularly for children. Access to health care for WIC participants has improved (Fox et al., 2003); at present more than 80 percent of WIC participants report some kind of health care insurance, primarily Medicaid or employer-sponsored insurance (Cole et al., 2001). Furthermore, evidence indicates that the Medicaid-enrolled children who participate in the WIC program have greater use of all health services, including preventive services and effective care of common illnesses, than the

Medicaid-enrolled children who are not WIC participants (Buescher et al., 2003). Despite these improvements, the prevalences of overweight and obesity in adults, adolescents, and children have increased dramatically—regardless of WIC participation.

From 1976 to 1994, among women of childbearing ages (20 through 39 years) the prevalence of being overweight increased (Kuczmarski et al., 1994) and the prevalence of obesity doubled (Flegal et al., 1998). Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 1999–2000 indicate that 28 percent of nonpregnant women aged 20 through 39 years are obese (Flegal et al., 2002). More recent data from NHANES 2001–2002 indicate that the prevalence of obesity among these women remains high at 29 percent (Hedley et al., 2004). Excess body fat and physical inactivity are associated with the development of hypertension, type 2 diabetes, coronary heart disease, dyslipidemia (e.g., abnormally high blood cholesterol), osteoarthritis, respiratory ailments, sleep problems, certain cancers (e.g., breast cancer), and all-cause mortality (Mokdad et al., 2004).

While there is no firm evidence that the WIC participant population is any more prone to being overweight than non-WIC populations (CDC, 1996a, 1996b), neither are they protected. Overweight and obesity are prevalent among minority groups, except for Asian Americans. The latter group is the fastest-growing ethnic minority in the country and still predominantly consists of first-generation immigrants. There is some evidence that overweight and obesity can be expected to become significant problems in these groups as well. Data from the most recent NHANES multistage probability sampling (1999–2002) estimate the overall prevalences of being overweight and obese at 70 and 47 percent for non-Hispanic black women, 62 and 31 percent for Mexican American women, and 50 and 25 percent for non-Hispanic white women, respectively (Hedley et al.,

2004). Of particular concern is the prevalence of Class 3 obesity (body mass index [BMI] equal to or greater than 40), which affects 15 percent of non-Hispanic black women ages 20 years and over, a prevalence nearly double that (7.9 percent) reported in the 1988–1994 NHANES (Flegal, et al, 2002). Moreover, women of low socioeconomic status disproportionately bear the burden of obesity and overweight regardless of race or ethnicity. Among individuals with less than a high school education, the prevalence is roughly twice that of college graduates (Mokdad et al., 1999).

Overweight in Children11

The prevalence of being overweight for children in the United States also has steadily risen over the last several decades (Jolliffe, 2004). Data from NHANES 1999–2000 indicate that the prevalence of being overweight was 15 percent in children ages 6 through 11 years as compared to 4 percent in 1965 (Ogden et al., 2002). In a 1999–2000 survey, 10 percent of children ages 2 through 5 years of age were overweight (Ogden et al., 2002). A 1998 survey of children participating in the WIC program found that 13 percent of these children were overweight (Cole, 2001). Being overweight in childhood and adolescence increases risk for overweight in adulthood (Serdula et al., 1993). Childhood overweight has been linked to adverse health outcomes including elevated blood pressure, hyperinsulinemia, glucose intolerance, type 2 diabetes, dyslipidemia, and other early risks for chronic disease, as well as to psychosocial problems including depression, social isolation, and low self-esteem (Dietz, 1998; Must and Strauss, 1999).

Nutrient Recommendations and Dietary Guidance Have Changed

New Nutrient Recommendations

Over the past decade, knowledge of nutrient requirements has increased substantially, resulting in a set of new dietary reference values called the Dietary Reference Intakes (DRIs) (IOM, 1997, 1998, 2000b, 2001, 2002/2005, 2005a). The DRIs replace the 1989 Recommended Dietary Allowances (RDAs) (NRC, 1989b) as nutrient reference values for the U.S. population. Based on the DRIs, many of the recommendations for nutrient intakes for individuals (that is, the RDAs) have changed substantially since the WIC food packages were originally formulated. Although basic concepts of nutrition have not changed, there has been a substantial increase in knowledge of specific concepts such as bioavailability, nutrient-nutrient interactions, and the distribution of dietary intake of nutrients across subgroups of the population. In addition to recommended intakes, the DRIs

include appropriate standards to use in determining whether diets are nutritionally adequate without being excessive. The DRIs encompass more aspects of nutrition than did the earlier RDAs, as follows:

-

DRIs consider reduction in the risk of chronic disease, as well as the absence of signs of deficiency.

-

For most nutrients, DRIs include both RDA and Estimated Average Requirement (EAR) values.

-

For some nutrients, insufficient data were available to set EAR and RDA values. For these nutrients, Adequate Intake (AI) values were estimated.

-

DRIs include Tolerable Upper Intake Levels (ULs), which are used in the evaluation of the risk of adverse effects from excess consumption.

-

DRIs specify appropriate ranges of macronutrient densities, which are called Acceptable Macronutrient Distribution Ranges (AMDRs).

-

When adequate data are available, DRIs provide reference values for food components other than nutrients.

New Dietary Guidance

At the time the WIC program was established, there was no systematic process for the development and revision of science-based dietary guidance for the U.S. population. However, guidance on food intakes is available now. Nutrition education tools such as the Four Food Groups focused on eating enough of various types of foods to ensure nutrient adequacy. The original selection of foods for the WIC food packages was based on food consumption data that indicated that calcium, iron, vitamin A, and vitamin C were the nutrients most likely to be low in the diets of low-income women and young children. Understanding of the necessity for adequate high-quality protein in periods of rapid growth and development provided the basis for inclusion of protein as a target nutrient. The specific foods selected for the food packages are good sources of the nutrients listed above, as well as widely available, generally acceptable, and reasonable in cost.

As deficiency diseases became less common, scientific research into the relationships between various dietary components and chronic diseases expanded. In 1977, the U.S. Senate Select Committee on Nutrition and Human Needs published Dietary Goals for the United States (U.S. Senate, 1977). This was the first government publication that set forth dietary guidance that included a focus on the total diet and recommendations both for minimizing risk of chronic disease and for ensuring nutritional adequacy. Much controversy surrounded these goals because of the lack of agreement among scientists on many of the issues and because of the pro-

cess used to set the goals (McMurry, 2003). A period of intense activity on the association between dietary components and chronic disease culminated in the 1979 Surgeon General’s Report on Health Promotion and Disease Prevention (DHEW/PHS, 1979). Then, in 1980, USDA and the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) jointly issued the first edition of the Dietary Guidelines for Americans (USDA/DHHS, 1980). The purpose was to provide the public with authoritative, consistent guidelines on diet and health. According to law (U.S. Congress, Pub. L. No. 101-445, 1990), the Dietary Guidelines form the basis of federal food, nutrition education, and information programs, including the WIC program.

Since 1980, the Dietary Guidelines, expressly intended for the general public ages two years and older, have been revised every five years. The Dietary Guidelines for Americans (DHHS/USDA, 2005) was released January 12, 2005. Those new guidelines are addressed in this report.

Many Stakeholders Are Calling for Change

In September 2003, USDA solicited public comments “to determine if the WIC food packages should be revised to better improve the nutritional intake, health and development of participants; and, if so, what specific changes should be made to the food packages” (FNS, 2003a). In response to this advanced notice of proposed rulemaking, the department received 195 letters. Respondents represented the general public, state and local WIC agencies, the National WIC Association, state WIC associations, industry, independent health professionals, vendors, WIC participants, and others. Comments received from the National WIC Association included two published position papers (NAWD, 2000; NWA, 2003) and provided recommendations based on that organization’s analysis of the evidence. In addition, the members of this committee received over 70 written and 30 oral public comments.

As anticipated, the comments represent a wide range of perspectives. In some cases, a substantial number of persons from a small geographic area submitted nearly identical comments. A majority of those who commented expressed general support for foods currently offered, but also proposed at least one change. Nearly three-fourths of those responding to USDA stated that fruits and vegetables should be added to the packages. Other comments addressed topics including priority nutrients, design and structure of the food package, amount of juice, amount of milk, choices of milk products, alternative sources of calcium, cereal and grain choices, forms of legumes (i.e., dried or canned dry beans or peas), peanut butter, eggs, tuna, alternative sources of protein, infant formula, medical foods regulations, cost, incentives to breastfeed, flexibility at the state agency level, and more variety and choice at the participant level (FNS, Advanced Notice of

Proposed Rulemaking [ANPRM], Revisions to the WIC Food Packages: Content Summary Analysis, March 2004). Comments submitted directly to this IOM committee addressed similar themes. Examples of the public comments are presented in Chapter 3—Process Used for Revising the WIC Food Packages.

CRITERIA FOR THE REDESIGN OF THE WIC FOOD PACKAGES

The WIC program is conceptualized as a supplemental nutrition program designed to improve health outcomes. The committee sees the role of the WIC food packages as improving the diet in ways that could have both short- and long-term health benefits. These include improving reproductive outcomes, supporting the growth and development of infants and children, and promoting long-term health in all WIC participants.

The definition of “supplemental” food is central to decision-making about the composition of the WIC food packages. The maximum allowances for formula in the current food package for the youngest formula-fed infants approach, and in some cases exceed, their total nutrient and food energy needs (Kramer-LeBlanc et al., 1999). For older WIC participants, the current WIC food packages are intended to increase dietary quality by improving intakes of the target nutrients, as well as meeting some of the food energy needs. For example, the current WIC food package for postpartum non-breastfeeding women supplies about one-third of food energy needs (Kramer-LeBlanc et al., 1999). Thus, the current WIC food packages are “supplemental” to different degrees for different WIC subgroups.

The WIC food packages not only supplement the diets of individuals, but augment the household’s economic resources. Although family expenditures are influenced by many factors (Rush et al., 1988b), there is some evidence that the nutritious foods in the WIC food packages replace other foods in the diet, resulting in greater nutrient density of the diet consumed (Wilde et al., 2000; Ikeda et al., 2002; Chandran, 2003). By supplying some foods, the WIC program frees up household funds, which then may be used to purchase other foods or necessities that benefit women and children (Basiotis et al., 1998).

The committee received positive feedback on proposed criteria published in its preliminary report, Proposed Criteria for Selecting the WIC Food Packages (IOM, 2004b). The criteria were slightly refined for greater clarity and are presented in Box 1-1. This final report addresses how the committee applied these criteria in developing its set of recommendations for changing the WIC food packages. The remainder of this section presents the rationale for each criterion, drawing on the preliminary report (IOM, 2004b). The criteria are also addressed briefly at the end of Chapter 3—

|

BOX 1-1

|

Process Used for Revising the WIC Food Packages—and in Chapter 6—How the Revised Food Packages Meet the Criteria Specified.

Criterion One: Addressing the Dual Problems of Undernutrition and Overnutrition

|

Designing supplemental food packages that optimize the potential benefit for long-term health poses mixed challenges. Problems of undernutrition still occur, but they must be addressed in the context of the current high prevalences of overweight and obesity. Some individuals remain at risk of inadequate intake of energy as well as of essential nutrients. Diets that provide excess food energy often provide inadequate amounts of essential micronutrients and other beneficial components of food. Depending on the amounts taken, the consumption of certain fortified foods could result in excessive intake of some micronutrients—possibly accompanied by inadequate intake of other nutrients. Thus, for example, the committee considered the potential impact of the amount and bioavailability of nutrients in fortified foods in the WIC food packages with regard to improving nutrient

intakes. Chapter 2—Nutrient and Food Priorities—addresses the committee’s analyses and findings regarding the prevalence of inadequate and excessive nutrient intakes. It also addresses nutrition-related health risks and outcomes of WIC-eligible populations.

Criterion Two: Consistency with the Dietary Guidelines for Americans

|

As stated previously, by law, both the supplemental food and the nutrition education provided by the WIC program need to be consistent with the Dietary Guidelines for Americans. To be as current as possible, the committee used the Report of the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee on the Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2005 to the Secretary of Health and Human Services and the Secretary of Agriculture (DHHS/USDA, 2004) as the basis for determining ways to meet this criterion. See Chapter 2—Nutrient and Food Priorities—for more information.

Criterion Three: Consistency with Recommendations for Infants and Children Younger Than Age 2 Years

|

Breastfeeding merits attention because breastfeeding rates by WIC mothers are far below the objectives set in Healthy People 2010 (DHHS, 2000a, 2000b; Ryan et al., 2002). The short duration of breastfeeding WIC infants is of special concern. The committee considered American Academy of Pediatrics recommendations for limiting juice intake and waiting to introduce complementary foods until the infant is developmentally ready. The committee also considered ways to avoid contributing to excessive intake of food energy. See Chapter 3—Process Used for Revising the WIC Food Packages—for more information.

Criterion Four: Suitability and Safety for Persons with Limited Transportation Options, Storage, and Cooking Facilities

|

In the 1998 WIC participant survey, 15 percent of WIC participants reported that limited transportation to grocery stores was a problem (Cole et al., 2001). Participants without automobiles may be able to take home only what they can carry, losing some value of their WIC food package. If it takes a long time to transport food to the home, perishable items, such as milk, may spoil, especially in hot weather. Spoilage may also occur if participants lack sanitary storage space or refrigeration or if perishable foods are supplied in packages that are larger than can be used in a reasonable or safe time. Where families share kitchen facilities and keep their foods locked in a private space, safely storing relatively large quantities of food may not be feasible. If foods (e.g., dried beans) need extensive cooking or preparation, lack of kitchen facilities, cooking knowledge, or time could also be a barrier to consuming those foods.

The packaging of food products has implications for food safety. For example, if a household uses only a part of the perishable food in a package on one occasion, safe storage is essential to minimize the risk of foodborne illness. Re-sealable packages or single-serving size packages may be needed to lessen the chance of food contamination, spoilage, or foodborne illness in some situations.

The ability to follow recommended cooking instructions, when applicable, also is important to keep foods safe. Proper cooking inactivates heat-labile, foodborne pathogens and toxins that occur naturally in raw foods. For example, eggs need to be cooked thoroughly to avoid foodborne illnesses.

Foods are not suitable for WIC food packages if two conditions apply: (1) they are particularly susceptible to contamination by organisms that cause foodborne illness; and (2) they result in serious adverse effects that are specific to a population that benefits from the WIC program. As an example, listeriosis is a foodborne illness considered potentially dangerous during pregnancy because it is associated with increased risk of spontaneous abortion, preterm birth, and fetal death. A surviving baby may succumb to respiratory distress and circulatory failure. New scientific knowledge about listeriosis as a hazard (CFSAN, 2003a) has generated changes in recommendations about the use of certain foods during pregnancy (CDC, 1998). Common foods that carry Listeria monocytogenes are ready-to-eat luncheon meats, hotdogs, and soft cheeses. Proper handling and cooking of food may help to lower the hazard of listeriosis. However, in some cases, especially where cooking is unlikely or inappropriate, certain foods are to be avoided during pregnancy (FSIS, 2001; Kaiser and Allen, 2002; CFSAN, 2003a).

Criterion Five: Acceptability, Availability, and Incentive Value

|

Food Acceptability

WIC-authorized foods need to fit the lifestyle of both employed and non-employed pregnant women and mothers of small children. As noted above in the section Why Consider Changes in the WIC Food Packages?, employment has increased in low-income households with children (GAO, 2001). Among women participating in the WIC program, the highest rate of employment is among pregnant women (32 percent) (Cole et al., 2001). Time constraints may push individuals, especially working parents, to use convenient, ready-to-heat, and ready-to-eat foods. In evaluating food items in the WIC food packages, the committee recognized that WIC participants are no more likely to desire or be able to spend considerable time in food preparation than the rest of the population. Suitable items for WIC food packages should not pose a heavy burden of food preparation for employed parents.

Foods Commonly Consumed

Changes in dietary patterns at population levels occur slowly and with concerted efforts at education and motivation (Bhargava and Hays, 2004; Burke et al., 2004; Cullen et al., 2004; MacLellan et al., 2004; Steptoe et al., 2004). To increase the likelihood that dietary changes will occur as a result of changes in the WIC food packages, the committee considered information about foods that are commonly consumed. Various sources indicate foods in each food group that are commonly consumed in the United States (Krebs-Smith et al., 1997; Smiciklas-Wright et al., 2002, 2003; Cotton et al., 2004). One source provides recent consumption data with breakdowns by variables such as age, gender, and quantities consumed per eating occasion (Smiciklas-Wright et al., 2002, 2003). The committee also used data concerning purchases of various foods, varieties of specific foods, brand names, and package sizes (ACNielsen, 2001).

From the public comments the committee received, it is apparent that some WIC participants feel the choice of foods in the current WIC food packages is very limited. Thus, the committee also took the position that participant acceptance of the food packages (and, as a result, improved eating patterns) might be increased if a wider variety of foods and choices were made available, especially for persons with different cultural backgrounds.

Participant Diversity

The WIC food packages must be suitable for participants in all 50 states, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, Guam, American Samoa, the American Virgin Islands, and 34 Indian Tribal Organizations (Kresge, 2003; FNS, 2004f). In addition, the WIC food packages need to be suitable to a growing number of migrant farm workers, particularly in California, Florida, and Texas (Kresge, 2003).

The need to consider diverse preferences due to cultural heritage applies across all regions and to food preferences of large and small cultural groups. Here, the term culture refers to groups of people who have shared beliefs, values, and behaviors and therefore may have needs differing from those of the general population (NWA, 2003). Culture may be defined by national, regional, and ethnic origins; religious affiliations; lifestyle (e.g., vegetarian); generation; or overlapping residence and socioeconomic variables.

Providing culturally acceptable foods does not necessarily mean that foods consumed most frequently by a cultural group should be offered in the WIC food packages. Some of those foods may be very low in the target nutrients or contain too much fat, sugar, cholesterol, or sodium. Also, WIC participants may have access to sufficient amounts of certain staple or core cultural foods (e.g., white rice, white potatoes), regardless of the contents of the WIC food packages (Kaiser et al., 2003). If the WIC food packages were designed to complement these core foods, they might serve as incentives for various cultural groups to participate in the WIC program.

The term culturally acceptable implies that the foods are easily accepted within the cultural norms of the participants. Studies have found that WIC participants from specific cultural groups have attitudes that value other foods above some of the foods provided in the current WIC food packages. For example, a study of women of Chinese descent living in California found that pregnant WIC participants value other sources of calcium (i.e., dark green vegetables and calcium-set tofu) more highly than the cheese provided in current WIC food packages (Horswill and Yap, 1999). To design culturally acceptable WIC food packages may require that the WIC program accommodate more substitutions than are allowed currently (Fishman et al., 1988; Story and Harris, 1989; Horswill and Yap, 1999; Pobocik et al., 2003). This is the position of the National WIC Association (formerly the National Association of WIC Directors) (NAWD, 2000; NWA, 2003).

Among immigrant subgroups, acculturation to the mainstream American culture results in dietary change (Lee et al., 1999; Neuhouser et al., 2004; Romero-Gwynn, et al., 1993) and sometimes results in excessive body weight gain (Goel et al., 2004). Dietary change often means that nutritious traditional foods are consumed less often, but some changes can

be positive. For example, a study among Korean Americans found that acculturation is correlated with increased consumption of oranges, tomatoes, fat-reduced milk, and bread (Lee et al., 1999). Ideally, the WIC food packages will promote positive dietary changes while supporting the beneficial components of traditional diets.

Some WIC participants have special conditions, such as milk allergies and lactose intolerance. Other WIC participants have diverse preferences, for example, choosing to avoid milk and other animal products for personal reasons unrelated to ethnicity or cultural heritage. Increasing flexibility at the state agency level in allowable substitutions to account for the needs and preferences of participants (or potential participants) may be a way to accommodate the culturally diverse preferences of the WIC participant population as a whole. Increasing variety and choices of options at the participant level may also be viewed as accommodating the culturally diversity of WIC participants.

Food Availability

Local food availability can influence dietary quality. As an example, most vendors in low-income neighborhoods are small, independent grocery outlets and convenience-type establishments that stock fewer selections and less fresh produce than do the larger, chain retail food stores that are predominantly in suburban and more affluent communities (Fisher and Strogatz, 1999; Morland et al., 2002a, 2002b, 2003; Cummins, 2003; Sloane et al., 2003). The presence of supermarkets in a community has been associated with increased intakes of fruits and vegetables by the local residents (Morland et al., 2002a). However, the greater the distance individuals live from a large chain grocery store, the poorer is their dietary quality (Laraia et al., 2004).

Vendors authorized to accept WIC vouchers are required to carry a sufficient stock of WIC-authorized foods (including specific brands and sizes) to ensure that participants can obtain their food prescription in one visit. The Food and Nutrition Service conducts studies of WIC food vendor management practices (Singh et al., 2003). Such studies found that 2.3 percent of larger vendors (i.e., outlets having 6 or more cashier registers) failed to carry sufficient stocks of WIC food items in 1998 (Singh et al., 2003). At the same time, 6.9 percent of small vendors (i.e., outlets having 1 to 5 cashier registers) did not have sufficient stocks of WIC food items (Singh et al., 2003). Although the percentage of vendors meeting inventory requirements for WIC-authorized foods for women and children substantially increased from 1991 to 1998, the percentage of vendors carrying sufficient stocks of infant package items decreased from 92.1 to 90.7 percent over the same period (Singh et al., 2003). In both the 1991 and 1998 studies, smaller

vendors were more likely than larger vendors to have insufficient stocks of WIC-authorized foods. In a study of barriers to the use of WIC services in the state of New York, 16 percent of 3,144 WIC participants noted that they sometimes or frequently find WIC-authorized food out of stock (Woelfel et al., 2004).

Incentive Value

The intent is to design WIC food packages that will serve as incentives for participation in the WIC program and promote healthy behaviors by participants. The packages should be viewed as valuable enough to promote and maintain enrollment in the WIC program and thus enable the participants to receive the dietary, educational, and health referral benefits that the WIC program provides. The food packages also should reinforce the WIC educational messages and promote long-term dietary quality.

A major objective for the nation is to promote the initiation of breastfeeding and support sustained breastfeeding through at least the infant’s first year (OWH, 2000). The current food packages provide an extra incentive to the fully breastfeeding mother solely by including more food and additional choices in Food Package VII. The committee considered ways that both the infants’ and mothers’ packages could be redesigned to provide greater incentive to breastfeed.

Criterion Six: Consideration of Administrative Impacts

|

Vendors

Increased vendor costs are potential consequences of increased flexibility, offering a wider variety of foods, allowing more options for participants, and other changes in the WIC food packages. Straightforward administrative procedures and efficient vendor checkout or food distribution would enhance the ease of program administration (Kirlin et al., 2003). The store that sells food to WIC participants must (1) have the designated types and package sizes of food available; (2) train checkout clerks to recognize the WIC-approved foods; (3) treat the WIC customers with respect; (4) organize an appropriate number of checkout stands to accept WIC customers; (5) train personnel to handle the redemption of WIC food instruments; and (6) carry the already sold inventory on their accounts until state payments are received. Implementation of specific changes in the WIC food packages has the potential to impact vendors to varying degrees in each of these areas.

Some changes in the WIC food packages would increase vendor costs. Requirements to procure a new business license to sell perishable (non-packaged) food could subject vendors to an increased frequency of inspection by state health departments (DHHS/PHS/FDA, 2001). In small stores or stores that serve WIC customers exclusively, arranging to have small loads of perishable products delivered on a regular basis has the potential to increase costs. The frequency of delivery could affect the quality of fresh fruits and vegetables. With the need for refrigeration and rapid turnover of perishables, the cost of distribution and inventory increases. In addition, special handling to ensure the safety of perishable products is needed. On the other hand, including more fruits and vegetables in the WIC food packages could mean that vendors are likely to sell more produce, a relatively high margin department in most stores.

The on-going initiative that will install electronic benefit transfer (EBT) systems in more locales may ease the transitions necessary in making changes to the WIC food packages. At present, however, such electronic systems and the efficiencies they achieve are not found in many vendor locations.

WIC Agencies

Changing the items in the WIC food packages or allowing greater flexibility in substitutions could pose administrative challenges at the state agency level. States and tribal organizations need to determine what products will be on their approved foods lists. Then they need to train vendors and monitor their compliance in allowing only WIC-approved foods. They also need to ensure appropriate training of personnel at local agencies.

Greater variety and choice by participants could pose a challenge at the local agency level. Local agencies must instruct participants, often with limited literacy skills, how to choose the allowed foods at the market. Increased complexity of the WIC food packages (i.e., number of items or options) could increase counseling time, waiting time, and staffing requirements at the local agencies. In a study of New York State WIC agencies, the most commonly cited barrier for participants was waiting too long at the local WIC clinic to receive services (Woelfel et al., 2004).

Currently, many state and local WIC agencies provide services to a large number of participants without the assistance of efficient electronic information technology. In 2001, over 50 percent of WIC state agencies had management information systems that were not capable of efficiently performing essential program tasks, such as tailoring food packages, assessing applicants’ income, or printing food vouchers (GAO, 2001). Thus, at present, efficient information technology systems cannot be counted on in every location to ease the transitions necessary in making changes to the

WIC food packages. In the future, changes may be more easily implemented through efficient information technology systems in more locales.

SUMMARY

The WIC program provides an average of 7.6 million women, infants, and young children each year with supplemental food. Changes in the food packages are warranted because of changes in demographics of the WIC population, in the food supply, in dietary patterns, in health risks, and in dietary guidance and recommendations. Together, these changes have created the current scenario in which the WIC food packages are inconsistent with dietary guidance and are in need of change to improve their acceptance by participants. Many stakeholders have called for changes in the WIC food packages based on changes in one or more of the areas listed above. The committee used the six criteria that appear in this chapter in making recommendations for changes to the WIC food packages. The remainder of this report addresses the processes used to develop recommendations for changes to the WIC food packages and the recommendations themselves.

-

Chapter 2—Nutrient and Food Priorities for the WIC Food Packages—identifies the priorities the committee set for revising the WIC food packages and discusses how those priorities were determined.

-

Chapter 3—Process Used for Revising the WIC Food Packages—discusses the process the committee used in redesigning the food packages.

-

Chapter 4—Revised Food Packages—presents the committee’s specific recommendations for revising the WIC food packages.

-

Chapter 5—Evaluation of Cost—estimates the costs of the food packages and variations of the packages, and compares estimated average per participant cost per month of the current and revised packages.

-

Chapter 6—How the Revised Food Packages Meet the Criteria Specified—relates the committee’s recommended package changes back to the criteria.

-

Chapter 7—Recommendations for Implementation and Evaluation of the Revised WIC Food Packages—presents the committee’s recommendations for effectively incorporating the revised food packages into the WIC program.

Overall, this report presents findings and other information intended to guide the Food and Nutrition Service of USDA to improve the supplemental food portion of the WIC program, improve the nutritional status of WIC participants, and, indirectly, to facilitate making the nutrition education component of the WIC program more consistent with the Dietary Guidelines for Americans.