1

The NASA Worksite

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) is the global leader in air and space exploration, research, and development. Throughout its history, NASA has demonstrated ingenuity, focus, and resilience in meeting the requirements of exacting, time-sensitive projects. NASA’s cultural legacy of believing that its workers can overcome complex technical challenges is reflected in the agency’s stated core values: safety, people, excellence, and integrity. As a result, both the manned space flight and the unmanned space probe missions have produced leading-edge programs. However, cultural traits and organizational practices that have fostered exceptional achievement may also affect employee health, well-being and productiveness and thus impact on mission success.

HOW AND WHY THE COMMITTEE WAS FORMED

NASA’s Director of Occupational Health requested that the Institute of Medicine’s Food and Nutrition Board, in consultation with the Board on Population Health and Public Health Practice, convene an ad hoc committee to prepare a report that would make recommendations to NASA’s Office of the Chief Health and Medical Officer (OCHMO) for (a) specific options for future worksite preventive health programs focusing on, but not limited to, nutrition, fitness, and psychological well-being; (b) incentives or methods to encourage employees to voluntarily enlist and sustain participation in worksite preventive health programs; (c) ways to create healthier workplace environments that are conducive to more active

lifestyles; (d) supportive nutrition options to reduce risk factors for chronic disease; and (e) ways to evaluate the effectiveness of such programs.

Worksite programs can reach large numbers of employees with information, activities, and services that encourage the adoption of healthy dietary and physical activity behaviors. For example, Irvine et al. (2004) evaluated an interactive multimedia program designed to encourage reduced consumption of dietary fat and increased consumption of fruits and vegetables at worksites. This study showed that the program had a positive impact on employee eating habits that was sustained at least 60 days following implementation. Other recent studies of worksite health promotion programs have found that both worksite and family-based interventions to increase fruit and vegetable consumption were similarly effective (Sorensen et al., 1999, 2004a). Worksite health promotion programs may reduce health care costs, including employer costs, for insurance programs, disability benefits, medical expenses, and employee sick leave (Aldana et al., 2005; Wright et al., 2004; Serxner et al., 2003).

A number of worksite health promotion activities have been instituted at NASA and are described on the NASA website (http://www.ohp.nasa.gov/). For example, at NASA Headquarters, nutrition counseling and physical activity interventions for employees with elevated serum cholesterol showed a trend of lowering serum low-density lipoproteins, a suggestive increase in high-density lipoproteins, and mild to moderate weight loss for the intervention group of employees (Angotti et al., 2000; Angotti and Levine, 1994). Uniform implementation of effective programs throughout the NASA system may provide significant improvements in employees’ physical and psychological well-being, and in turn benefit the agency.

HISTORY OF NASA AND DEVELOPMENT OF NASA CULTURE

Historical Development of NASA

Historical Timeline

Before the formation of NASA, research aimed at putting a U.S. astronaut in space was conducted primarily by the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics in cooperation with other federal organizations. NASA was formed in 1958 in response to the first successful launch and flight of Sputnik by the Soviet Union (http://www.history.nasa.gov/). At a time when the United States was engaged in a Cold War with the Soviet Union and was concerned about national defense, the successful launch of Sputnik indicated that the United States lagged behind in technological development.

The mission of the first NASA project, Mercury, was to learn whether humans could survive in space. Subsequent mission projects included Gemini during the 1960s, then Apollo, which ultimately landed the first astronauts on the moon in 1969. The Skylab and Apollo-Soyuz Test Projects were initiated in the 1970s. The Space Shuttle Program and the International Space Station developed from these initiatives during the 1980s and 1990s. NASA has launched several unmanned probes, such as Pioneer, Voyager, and the Hubble Space Telescope, in addition to its manned missions, and space science programs have been carried out to Earth’s moon and all planets in our solar system except Pluto. Together, these projects have yielded NASA many successes with few tragic failures (Table 1-1) (http://www.history.nasa.gov/).

TABLE 1-1 Draft Timeline of NASA History

|

Chronology |

Policy Events |

Mission Events |

|

1958 |

NASA began operation |

Pioneer 1: NASA’s first launch |

|

1960 |

|

Mercury 1: Mercury-Redstone Capsule-launch vehicle combination. Unoccupied test flight |

|

1961 |

President Kennedy announced that he was committed to landing a man on the moon |

Mercury Astronaut program: human space flight initiatives to see if humans could survive in space, 1961-1963 Mercury 2: Chimpanzee Ham was sent into suborbital space for 16.5 minutes Alan Shepard became the first American to fly in space: Mercury spacecraft Freedom 7 |

|

1962 |

|

John Glenn becomes first American to orbit the Earth: Mercury spacecraft Friendship 7 |

|

1965 |

Project Gemini is implemented: Flights, 1965-1966 |

Gus Grissom and John Young: first operational mission of Project Gemini with Gemini 3 Ed White became the first American to complete a spacewalk: Gemini 4 |

|

1967 |

Project Apollo is implemented: Flights, 1967-1972 |

Apollo-Saturn (AS) 204 (Apollo 1): First death directly attributable to U.S. Space program. Gus Grissom, Ed White, and Roger Chaffee died as a result of a fire on the launch pad |

|

Chronology |

Policy Events |

Mission Events |

|

1969 |

|

Apollo 11: Neil Armstrong walked on the moon |

|

1970 |

|

Apollo 13: An oxygen tank burst halfway through the journey to the moon. The crew improvised to end the mission safely |

|

1975 |

|

Apollo-Soyuz Test Project: first international human space flight |

|

1981 |

Space Shuttle Program is implemented |

Columbia 1st launch |

|

1983 |

|

Challenger 1st launch |

|

1984 |

|

Discovery 1st launch |

|

1986 |

Office of Safety, Reliability, Maintainability and Quality Assurance was created in response to the Challenger investigation Report of the Presidential Commission on the Space Shuttle Challenger Accident and Implementation of the Recommendations |

Space Shuttle Challenger was lost during launch killing all 7 astronauts on board |

|

1988 |

|

Discovery launch, first flight after Challenger disaster |

|

1990 |

Future of U.S. Space Program Advisory Committee issued a report outlining chief objectives of the agency and recommendations of key actions relating to a need to create a balanced program of human space flight, robotics probes and space science within a tightly constrained budget |

Launch of the Hubble Space Telescope |

|

1992 |

|

First flight of Space Shuttle Endeavor |

|

1995 |

|

Atlantis docked with Mir Space Station (Russian space lab) |

|

1996 |

“NASA announced that scientists had uncovered evidence, however not conclusive proof, that microscopic life may have existed on Mars” |

Atlantis docked with Mir, Shannon Lucid was left aboard for 5 months |

|

1997 |

|

Mars Pathfinder landed on Mars Cassini Space Probe was launched to Saturn |

|

Chronology |

Policy Events |

Mission Events |

|

1998 |

International Space Station agreement signed by 15 countries |

|

|

1999 |

|

Mars Polar Lander reached Mars but was lost during the landing sequence; “not known whether the probe followed the descent path or was lost in some other manner” Mars Climate Orbiter: Contact with spacecraft was lost after it passed behind Mars due to some commands being sent in English units instead of being converted to metric. The spacecraft missed its intended altitude above Mars. Atmospheric stresses and friction at a lower altitude would have destroyed the spacecraft |

|

2000 |

|

Expedition One International Space Station: First permanent crew was sent to the ISS |

|

2003 |

The Columbia Accident Investigation Board released its final report |

The Space Shuttle Columbia was lost just before landing killing all seven astronauts on board |

|

2004 Saturn |

The President’s Commission on |

Cassini Space Probe arrived at |

|

|

Moon, Mars and Beyond delivered its report entitled “A Journey to Inspire, Innovate and Discover” to the White House. |

Genesis Capsule returns to earth with particles of the Sun |

|

SOURCE: http://www.hq.nasa.gov/office/pao/History/40thann/define.htm. |

||

Historical Development of the NASA Culture

The challenge posed by President John F. Kennedy in 1961 to put a man on the moon before the end of the decade, and the subsequent “space race” with the Soviet Union fostered a “can-do” and insular culture at NASA, which was further solidified in the era of the Apollo missions. Faced with a series of seemingly impossible tasks, the agency’s workforce and leadership were required to achieve high goals and expectations in full view of the American people. Also required was the recognition that there were many risks in the frontier of space and that there would be failure on occasion, as an inevitable consequence of working in the unknown environment of space beyond the Earth’s atmosphere (CAIB, 2003).

During the Apollo missions between 1967 and 1975, political and financial support were stronger than has been the case in recent years, which have been characterized by budgetary constraints and downsizing. The Nixon administration directed that the NASA budget be reduced as much as was politically feasible. When the Space Shuttle Program was proposed in 1971 with an estimated cost of $5.15 billion, funding was approved, with a subsequent cost ceiling of $5.5 billion imposed by the President’s Office of Management and Budget. Because the original cost estimate was overly optimistic, the cost ceiling placed NASA in the position of making a number of trade-offs to achieve a savings on the project, even though future operational costs would increase.

The engineering expertise, dedication, and “can-do” culture of NASA’s engineers, however, overcame these obstacles and successfully produced a reusable shuttlecraft on a constrained budget. Unfortunately, the image of the space shuttle as a safe vehicle that could be operated routinely with little risk was shattered in 1986 when the agency experienced the tragic loss of the space shuttle Challenger.

In response to the Challenger accident, an independent commission determined that the shuttle program’s constrained, decentralized budget resulted in inadequate resources and personnel limited in independence and authority, which contributed to risks in mission safety (NASA, 1986).

The Columbia Accident Investigation Board (CAIB) identified similar issues that led to failures in communication and weakening of the safety system, culminating in the loss of Columbia in 2003 (CAIB, 2003).

Policy Reports to NASA

The CAIB conducted an independent investigation of the loss of the space shuttle Columbia in 2003. The CAIB determined that the accident was not likely an anomalous, random event—rather, it was more likely rooted in the history and culture of NASA (CAIB, 2003). The report clearly identified attributes of NASA that contribute positively to the safety climate, including a robust and independent program technical authority that has control over specifications and requirements, as well as over waivers to them; an independent safety assurance organization with line authority over all levels of safety oversight; and an organizational culture that reflects the best characteristics of a learning organization (CAIB, 2003). It also identified organizational weaknesses that contributed to the accident, including compromises that were required to gain approval for the shuttle, years of resource constraints, fluctuating priorities, schedule pressures, mischaracterization of the shuttle as operational rather than developmental, and lack of an agreed national vision for human space flight (CAIB, 2003).

Effect of NASA Culture on Organizational Goals

The culture of an institution or organization encompasses its basic values, norms, beliefs, and practices. The culture that characterizes the NASA organization has its origins in the Cold War environment of the late 1950s and early 1960s (CAIB, 2003) and in its military background and engineering focus. This culture emphasizes a top-down approach to organizational management, in which decisions are made by upper-level managers and administrators and carried out by the workforce.

In large part, the success of NASA’s programs is the result of clear and forward-thinking goals set by NASA scientists, engineers, and administrators and carried out by a highly motivated and resourceful workforce that embraces challenge and periods of exceptionally high demand. The successes enjoyed by NASA may be attributable to its cultural traits and organizational practices; however, this same culture that contributed to achievement of exceptional mission success may also have affected employee safety, health, and productivity.

Assessment and Plan for Organizational Culture Change at NASA

Following the loss of the shuttle Columbia, NASA asked Behavioral Science Technology, Inc. (BST), to assist in the development and implementation of a plan for changing the safety climate and culture within the agency. An important observation noted in this 2004 study was NASA’s approach to defining and executing projects. Although NASA’s emphasis on addressing tasks with a discrete beginning and ending point allows the agency to accomplish challenging technical missions, it may also hinder the agency in addressing cultural issues that underlie the need for safety climate change within the organization.

The BST study also surveyed NASA personnel on their perceptions of the safety climate and culture within the agency. The results indicate that, in relation to other organizations, NASA scores well in areas such as approaching others, work-group relations, reporting, social efficacy, teamwork, and leader/member exchange. Two areas in which NASA scored lowest were perceived organizational support and upward communication. The lower scores in these areas indicate the need for focus to effect a successful culture change. Notably, the study points out that perceived organizational support and upward communication are factors that strongly influence the way that culture relates to mission safety.

Overall, the BST study concluded that an organization’s strong task orientation at the expense of relationship orientation can lead to inhibition of upward communication and weak perceived organizational support. A successful culture change initiative in NASA should build from its

strengths, but it should also move toward integrating the values of safety and people into the fabric of the organization by helping management to effectively balance task orientation and relationship orientation, thus creating a culture that will more effectively support NASA’s mission.

ORGANIZATION OF NASA

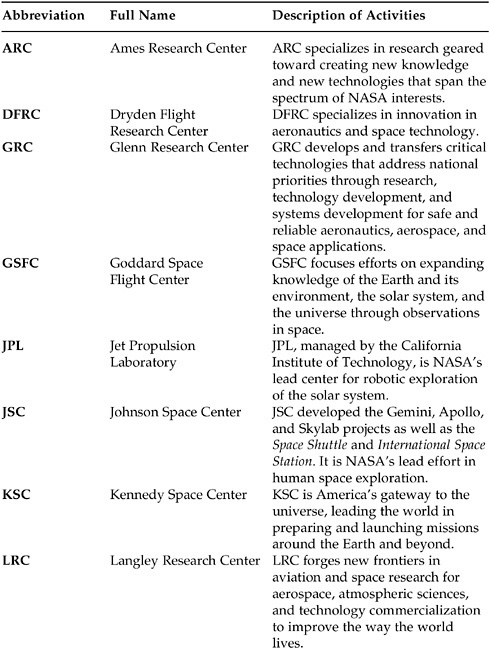

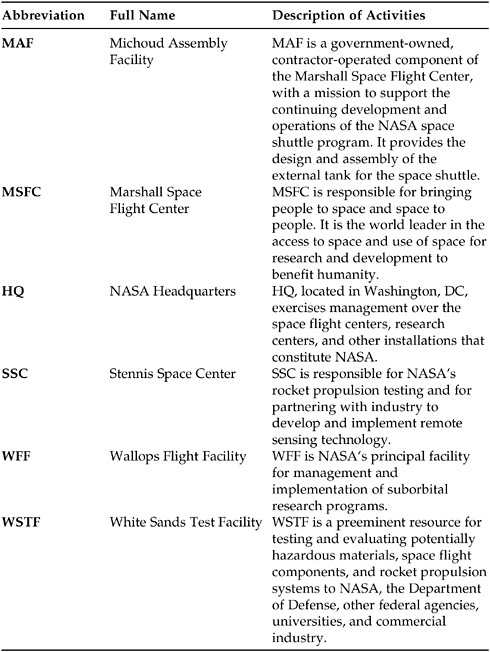

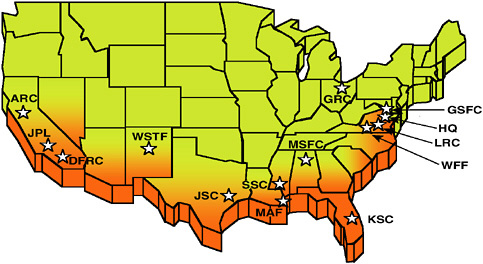

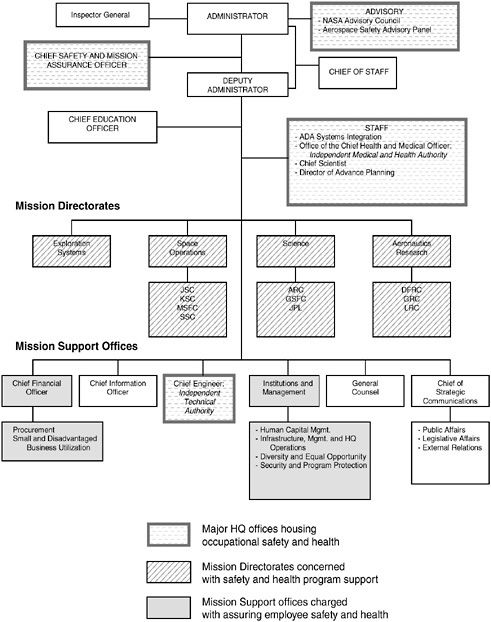

NASA includes 14 worksites in 10 states across the United States plus the District of Columbia (Figure 1-1). Within the NASA organizational structure (Figure 1-2), there are more than 72,000 employees working at these sites. Approximately 25 percent of the total workers are federal employees, and 75 percent are on-site contractors, although the workforce composition varies at each site (Probst, 2004). A breakdown of the NASA workforce by center is shown in Table 1-2.

The NASA Work Environment

The NASA work environment is highly variable, comprising deep space, near space, land, and sea. For example, NASA aquanauts in the

FIGURE 1-1 NASA centers and facilities.

SOURCE: Probst, 2004.

FIGURE 1-2 NASA ORGANIZATIONAL CHART (as of May 2005). The Mission Directorates support both Directorate-level and NASA-wide visions and goals. The office of the Chief Financial Officer is responsible for contracting specifications, procurement services, financial-related health metrics, and total cost accounting. The Office of Institutions and Management directly impacts the health and well-being of employees and the workplace environment.

TABLE 1-2 Approximate Size of NASA Workforce by Site

|

NASA Site |

Federal Employees |

Contractors |

Total |

|

Ames (ARC) |

1,456 (26 percent) |

4,180 (74 percent) |

5,636 |

|

Dryden (DFRC) |

621 (24 percent) |

1,981 (76 percent) |

2,602 |

|

Glenn (GRC) |

1,937 (56 percent) |

1,500 (44 percent) |

3,437 |

|

Goddard (GSFC) |

3,100 (41 percent) |

4,500 (59 percent) |

7,600 |

|

Headquarters (HQ) |

1,100 (81 percent) |

250 (19 percent) |

1,350 |

|

Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) |

58 (1 percent) |

9,118 (98 percent) |

9,176 |

|

Johnson (JSC) |

3,112 (30 percent) |

7,251 (70 percent) |

10,363 |

|

Kennedy (KSC) |

1,831 (14 percent) |

11,057 (86 percent) |

12,888 |

|

Langley (LRC) |

2,348 (62 percent) |

1,420 (38 percent) |

3,768 |

|

Marshall (MSFC) |

2,731 (38 percent) |

4,527 (62 percent) |

7,258 |

|

Michoud (MAF) |

14 (1 percent) |

2,307 (99 percent) |

2,321 |

|

Stennis (SSC) |

291 (6 percent) |

4,390 (94 percent) |

4,681 |

|

Wallops (WFF) |

250 (22 percent) |

876 (78 percent) |

1,126 |

|

White Sands (WSTF) |

60 (9 percent) |

615 (91 percent) |

675 |

|

TOTALS |

18,909 (26 percent) |

53,972 (74 percent) |

72,881 |

|

SOURCE: Probst, 2004. |

|||

Extreme Environment Mission Operations project conduct both human and environmental research on the NEEMO, an underwater laboratory off the coast of Florida. In contrast, other employees at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory spend their day in an environmentally-controlled, artificially-lit laboratory. Some employees work in an office environment, while others spend their days outside or in assembly buildings. Employees in some NASA environments are subjected to hazardous conditions and materials such as jet and rocket fuels, radiation, and hazardous chemicals, or to psychologically stressful conditions such as may exist when mission deadlines are approaching.

The NASA Workforce

As a world-class science and engineering agency, NASA requires a world-class workforce to carry out its objective for “One NASA,” with integrated capabilities to support its missions (see http://www.nasa.gov/). This workforce is, by necessity, variable in its skills and educational levels and is very diverse, comprising not only professional scientists and engineers, but also technicians, service staff, and a range of highly specialized personnel. As previously stated, the majority of the workforce is made up of contracted employees. Only about 25 percent of the NASA workforce

are civil servants (Probst, 2004). Within both of these groups, a range of work skills, both blue-collar and white-collar, is represented. These differences increase the difficulty of supporting worker health in ways that meet employee needs (e.g., smoking cessation, physical fitness training) while avoiding disparities in the provision of health care and other preventive services (Sorensen et al., 2002, 2004b).

A number of impediments to maintaining a diverse and competitive workforce also have been identified by NASA. These include, at the nationwide level, a shrinking science and engineering resource pool, increased competition with the private sector for technical skills, and a lack of diversity within the applicant pool; and at the agency level, an imbalance in skills and lack of depth in critical competencies, significant loss of knowledge resulting from projected retirements, and increased recruitment and retention problems.

The goal of NASA’s recruitment efforts is to bring in the “best and brightest” scientists and engineers, as well as highly competent support staff, to maintain the agency’s technical programs and address its financial, acquisition, and business management challenges (see http://www.hq.nasa.gov/office/codee/index.html). Essential to this effort is providing, through its occupational health services, the tools and competencies needed to support a workforce that is healthy, productive, ready, and resilient.

THE CHARGE TO THE COMMITTEE

The Institute of Medicine’s Committee on Assessing Worksite Preventive Health Program Needs of NASA Employees was charged to assess existing worksite preventive health programs and assess employee awareness and attitudes concerning these existing programs. Using previously gathered data and other research sources, the committee was asked to determine whether there are chronic disease issues unique to the NASA work environment. The committee further was asked to prepare a report that evaluates and recommends (a) specific options for future worksite preventive health programs focusing on, but not limited to, nutrition, fitness, and psychological well-being; (b) incentives or methods to encourage employees to voluntarily enlist and sustain participation in worksite preventive health programs; (c) ways to create healthier workplace environments that are conducive to more active lifestyles; (d) supportive nutrition options to reduce risk factors for chronic disease; and (e) ways to evaluate the effectiveness of such programs.

Approach to the Task

The committee approached its charge by gathering information from existing literature and from workshop presentations by recognized experts (see Appendix B for the workshop agenda), commissioning an analysis of NASA worksite preventive health programs, deliberating on issues relevant to the task, and formulating an approach to address the scope of work. Reports and other data releases, such as the analysis by the Health Enhancement Research Organization (HERO), the CAIB’s report, and Healthy People 2010, were included in the committee’s research (Kennedy et al., 1998; CAIB, 2003; USDHHS, 2000). In addition, the committee conducted site visits to six NASA centers. These visits included observations of occupational health-related programs and activities; interviews with leadership, including where possible the center director or associate director; and focus group interviews with employees (see Chapter 2 for site visit summary).

The committee’s recommendations, following the analysis of gathered data and commissioned work, include those interventions that the committee determined would be both feasible and effective in meeting the goal of NASA’s Chief Health and Medical Officer to ensure that employees who join NASA should end their careers healthier than employees in other organizations as a result of their experience with NASA’s occupational and preventive health programs.

Organization of the Report

The report is organized into six chapters that describe NASA as an organization and discuss the role of Occupational Health in NASA and in other organizations, both public and private. The report presents examples of successful preventive health programs “best practices,” as well as strategies for optimizing the preventive health options offered to the NASA workforce. Chapter 2 describes Occupational Health at NASA, including the range of programs and a summary of committee observations from visits to selected centers. Chapter 3 presents a healthy workforce paradigm and makes the case for change based on current best practices at NASA and in other organizations. Chapter 4 describes the elements required for organizing and managing effective workplace wellness programs. Chapter 5 describes the integration of health and wellness in worksite health promotion. Finally, Chapter 6 reviews integrated health data management systems.

REFERENCES

Aldana SG, Merrill RM, Price K, Hardy A, Hager R. 2005. Financial impact of a comprehensive multisite workplace health promotion program. Preventive Medicine 40(2):131–137.

Angotti CM, Levine MS. 1994. Review of 5 years of a combined dietary and physical fitness intervention for control of serum cholesterol. Journal of the American Dietetic Association 94(6):634–638.

Angotti CM, Chan WT, Sample CJ, Levine MS. 2000. Combined dietary and exercise intervention for control of serum cholesterol in the workplace. American Journal of Health Promotion 15(1):9–16.

BST (Behavioral Science Technology). 2004. Assessment and Plan for Organizational Culture Change at NASA. Ojai, CA: BST.

CAIB (Columbia Accident Investigation Board). 2003. Report, Volume 1. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Irvine AB, Ary DV, Grove DA, Gilfillan-Morton L. 2004. The effectiveness of an interactive multimedia program to influence eating habits. Health Education Research 19(3):290–305.

Kennedy S, Wasserman J, Merrick N, Dunn RL, Goetzel RZ. 1998. The Effects of Modifiable Health Risk Factors on Coronary Artery Disease-Related Expenditures and Hospitalizations: A National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) Study. Birmingham, AL: The Health Enhancement Research Organization (HERO).

NASA (National Aeronautics and Space Administration). 1986. Report of the Presidential Commission on the Space Shuttle Challenger Accident (Rogers Commission Report). Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Probst TM. 2004 (March 25). Preventive Health at NASA: A Summary of Occupational Health Programs and Employee Utilization. Presented to the Institute of Medicine’s Food and Nutrition Board Committee to Assess Worksite Preventive Health Program Needs for NASA Employees, Meeting #1.

Serxner SA, Gold DB, Grossmeier JJ, Anderson DR. 2003. The relationship between health promotion program participation and medical costs: A dose response. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 45(11):1196–1200.

Sorensen G, Stoddard A, Peterson K, Cohen N, Hunt MK, Stein E, Palombo R, Lederman R. 1999. Increasing fruit and vegetable consumption through worksites and families in the Treatwell 5-a-day study. American Journal of Public Health 89(1):54–60.

Sorensen G, Stoddard A, LaMontagne A, Emmons K, Hunt MK, Youngstrom R, McLellan D, Christiani D. 2002. A comprehensive worksite cancer prevention intervention: Behavior change results from a randomized controlled trial (United States). Cancer Causes and Control 13(6):493–502.

Sorensen G, Linnan L, Hunt MK. 2004a. Worksite-based research and initiatives to increase fruit and vegetable consumption. Preventive Medicine 39(Suppl 2):S94–S100.

Sorensen G, Barbeau E, Hunt MK, Emmons K. 2004b. Reducing social disparities in tobacco use: A social contextual model for reducing tobacco use among blue-collar workers. American Journal of Public Health 94(2):230–239.

USDHHS (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services). 2000. Healthy People 2010. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Wright D, Adams L, Beard MJ, Burton WN, Hirschland D, McDonald T, Napier D, Galante S, Smith T, Edington DW. 2004. Comparing excess costs across multiple corporate populations. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 46(9):937–945.

Websites: