1

The Role of Veterinary Research in Human Society

“Between animal and human medicine there is no dividing line—nor should there be. The object is different but the experience obtained constitutes the basis of all medicine.” Rudolf Virchow (1821–1902)

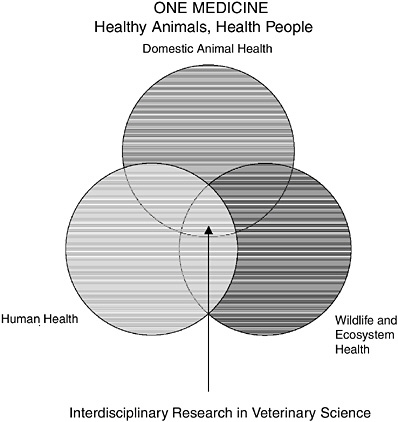

Virchow’s statement is as wise today as it was over a century ago. That all animal species, including Homo sapiens, are related and that knowledge gained in one species benefits all lead to the concept of “One Medicine”. The One Medicine approach takes advantage of commonalities among species; few diseases affect exclusively one group of animals (wildlife, domestic animals, or humans). On the basis of that view, Schwabe (1984) asserts that veterinary medicine is fundamentally a human health activity. All activities of veterinary scientists affect human health either directly through biomedical research and public health work or indirectly by addressing domestic animal, wildlife, or environmental health. Moreover, veterinary scientists have a responsibility to protect human health and well-being by ensuring food security and safety, preventing and controlling emerging infectious zoonoses, protecting environments and ecosystems, assisting in bioterrorism and agroterrorism preparedness, advancing treatments and controls for nonzoonotic diseases (such as vaccine-preventable illnesses and chronic diseases), contributing to public health, and engaging in medical research (Pappaioanou, 2004). Just as the practice of veterinary medicine contributes to our understanding of all medicine or One Medicine, so must veterinary research. It follows that veterinary research is, at a fundamental level, a human health activity. The centrality of veterinary research and its critical role at the interface between human and animal health are often not understood and undervalued. A vision for veterinary research and its contribution to advancing One Medicine and providing solutions for today’s and tomorrow’s animal and human health problems is illustrated below (Figure 1-1).

FIGURE 1-1 A vision for veterinary research. The One Medicine approach to human and animal health emphasizes the interconnectedness of relationships and the transferability of knowledge in solving health problems in all species.

Veterinary research includes research on prevention, control, diagnosis, and treatment of diseases of animals and on the basic biology, welfare, and care of animals. Veterinary research transcends species boundaries and includes the study of spontaneously occurring and experimentally induced models of both human and animal disease and research at human-animal interfaces, such as food safety, wildlife and ecosystem health, zoonotic diseases, and public policy.

By its nature, veterinary science is comparative and gives rise to the basic science disciplines of comparative anatomy, comparative physiology, comparative pathology, and so forth. Veterinary research occurs in colleges of veterinary medicine, human medicine, dentistry, agriculture, and life sciences; it is done by veterinarians, physicians, and other nonveterinarians in many disciplines. For 2 centuries, responsible public officials have recognized that veterinary research protects our draft animals, our supplies of meat and eggs, and our wildlife. It also

advances our ability to maintain the health of all animals, domestic and wild; and informs policy decisions—for example, regulations to prevent and control tuberculosis and brucellosis in dairy cattle. During the same period, scientists have acknowledged the broad and robust contributions of veterinary research to human health.

Veterinary research has the potential to immensely impact the fields of comparative medicine, public health and food safety, and animal health; but its ability to reach its potential relies on adequate infrastructural, financial, and human resources. The National Research Council convened an ad hoc committee to assess the status and future of veterinary research in the United States on the request of the American Animal Hospital Association, the Association of American Veterinary Medical Colleges, the American Veterinary Medical Association, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the National Association of Federal Veterinarians, the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), and the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. Specifically, the committee was asked to identify national needs for research in three fields of veterinary science—comparative medicine, public health and food safety, and animal health; to assess the adequacy of our national capacity, mechanisms, and infrastructure to support the needed research; and, if appropriate, to make recommendations as to how the needs can be met. Specific budgetary or organizational recommendations were not to be included in the report. (Appendixes A and B present the complete statement of task and information on the committee members.)

The three fields of veterinary science encompass research with domestic animals (such as livestock and poultry), wild animals (such as deer and exotic species), companion animals (such as dogs, cats, and horses), service animals (such as horses and dogs), and laboratory animals. Specifically, future needs for research were assessed in the three fields of veterinary science, which are not limited to science conducted by veterinarians; they include science performed by professionals who have veterinary degrees and professionals who have various other degrees.

HISTORY

The contributions of veterinary research to advancements in medicine are rich. In ancient academic amphitheaters, comparative anatomical and physiological studies provided a basis for our understanding of embryonic development, human blood circulation and lymphatics, the brain and the rest of the nervous system, and the structure of virtually all organs. As modern medicine evolved, Pasteur’s experiments on rabies and anthrax vaccination in sheep, Koch’s studies of tuberculosis, and Salmon’s direction of research in the US Bureau of Animal Industry—all of which depended on the knowledge of comparative or veterinary research—provided the basis of contemporary preventive medical treatments. More recent contri-

butions of veterinary researchers include Brinster’s pioneering studies in embryo transplantation and the immunological discoveries of Nobel Prize winner Peter Doherty. In the last half century, the widespread use of animal models in comparative medicine and the improved management of laboratory animals have been integral to the advancement of scientific knowledge in human medicine.

In 1878, Congress appropriated $10,000 for the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) to fund the first research in the United States specifically directed toward veterinary science. This study was “investigating diseases of swine and infectious and contagious diseases which all other classes of domestic animals are subject” and enabled D.E. Salmon to establish that quarantine and disinfection prevent spread of infectious diseases. Salmon’s successful research led to an act of Congress on May 29, 1884, that established the Bureau of Animal Industry (BAI) in USDA. The act provided, in part, “that the Commissioner of Agriculture shall organize in this Department a Bureau of Animal Industry, and shall appoint a Chief thereof, who shall be a competent veterinary surgeon.” Research in BAI made major scientific advances in the understanding of human diseases. BAI’s findings included the isolation of the first species of Salmonella, the discovery of hog cholera and of how the virus and serum provide immunity, elucidation of the life cycle of the cattle tick, and the discovery of the protozoan parasite that caused Texas cattle fever. The latter made possible the scientific approach to conquering yellow fever in the Panama Canal Zone. In 1920, Simon Flexner of Rockefeller Institute of Medical Research noted that “our knowledge of yellow fever would in all likelihood have been delayed if the work of the Bureau of Animal Industry of the US Department of Agriculture on Texas fever had not been done.”

BAI was a major contributor to public health, Secretary of Agriculture James Wilson’s report for 1909 stated that the BAI “not only deals with the livestock industry, but has an important bearing upon public health through the meat inspection, through efforts for the improvement of the milk supply, and through the investigations, prevention and eradication of diseases which affect man as well as the lower animals. Indeed, the animal and the human phases of the Bureau’s work are so closely related and interwoven that they could not be separated without detriment.”

At the turn of the twentieth century, the university-based schools of veterinary medicine began to develop research units. Advanced medical institutions included comparative medicine in their structure and used animal disease models to elucidate the basic nature of human disease. Rous, in 1910, was the first to discover a virus that caused cancer (sarcoma in chickens). Other discoveries in comparative medicine include Shope’s findings of the viral nature of papillomas in rabbits (1932) and Bittner’s finding that viruses in milk cause mammary gland tumors in mice (1936). In 1938, the association of a bleeding disorder of cattle with sweet clover stimulated the search for the toxicant; it was found to be dicumarol, which was quickly developed as an anticoagulant for humans and as a rodenticide for public health.

Three factors led to a marked increase in veterinary research in the massive economic growth and academic reformation that followed World War II. First, the number of veterinary schools with specific dedication to veterinary research doubled. Second, veterinarians were specializing; they formed the American College of Veterinary Pathologists, the American College of Veterinary Preventive Medicine, and subspecialties with expertise in fields related to public health and medical science. Third, animal models were being used to make major advances in basic research, and institutions of veterinary science had access to the newly developing federal funding mechanisms. Veterinary scientists made contributions in the pathogenesis of yellow fever, plague, and smallpox. Gross isolated a virus that caused naturally occurring lymphomas in mice (1951), and Jarrett discovered that retroviruses were responsible for the transmission of leukemia among cats (1964). Brinster and Mintz inoculated teratoma cells into normal mouse blastocysts to produce normal but mosaic mice and showed that tumor cells lose malignancy and differentiate normally (1974). Slemons and Easterday discovered that wild ducks were a reservoir of avian influenza viruses (1974).

In recent times, the application of molecular biology to problems in veterinary science has blurred the distinction between medical science and veterinary science in many fields. As microbial and genetic discoveries were made, pathogenesis studies were required to integrate the new knowledge into useful clinical advances. Those advances include a creative model of enteric bacterial disease (Moon), demonstration of the transmissibility and pathogenesis of scrapie, a proposal that human kuru was a transmissible spongiform encephalopathy (Hadlow), and the isolation of bovine leukemia virus (Miller) and bovine immunosuppressive retroviruses (Van Der Maaten)—5 years before AIDS and HIV appeared. Now modern molecular and genetic sciences and their applications in integrative, whole-animal biology make possible exciting advances for the benefit of both animals and people.

CONTEMPORARY ISSUES IN VETERINARY SCIENCE

The historical contributions of veterinary research have been considerable, but its vital role in public health and food safety has been brought into stark reality in the last 2 decades. Concerns have been driven by the recognition that many emerging infectious diseases of humans are zoonotic (NRC 2002a). Such diseases as Escherichia coli O157:H7 infection, bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE), and avian influenza highlight the importance of research to improve veterinary public health and food safety. There is a need for more research on those diseases and many others, such as anthrax and Rift Valley fever, that may be used in terrorist attacks through agriculture and the food supply.

The need for research on animal health problems that do not threaten public health or food safety was emphasized by the 2001 outbreak of foot-and-mouth disease in the United Kingdom. The economic consequences of the outbreak—

through the loss of domestic and international trade and tourism and the costs of the eradication program—were devastating. Current knowledge and technology for preventing or responding to such a disease do not meet increasing public expectations for food security and are not adequate to mitigate the risks posed by the globalization of agriculture and increasing world travel and trade in animals and animal products or the threat of agricultural bioterrorism.

Veterinary research has evolved to address societal changes. Companion animals play a central role in the quality of life of an increasing proportion of the public; the beneficial psychosocial effects of the human-animal bond are widely accepted. Companion animals are also important sentinels for human disease and toxicant exposure, and companion-animal research improves our understanding of zoonotic diseases and how to address them; diagnostic and therapeutic data from companion animals can often be translated to human medicine. Because the health, well-being, and longevity of companion animals are a growing concern for a substantial portion of society, demand for research on companion animal health and disease has increased; indeed, it is crucial for improving the health and welfare of these animals, which serve not only as companions, but as aides, detectives, and soldiers.

In addition to the health of food and companion animals, the health of wildlife and ecosystems is of special importance to an increasingly urban and affluent society. The countryside is increasingly affected by urban development and industrial agriculture. There is growing concern about wildlife preservation and endangered species and growing recognition of the value of wildlife as sentinels for environmental health generally. The emergence of Lyme disease in the human population of New England partly due to changing land-use patterns and of Chronic Wasting Disease (a transmissible spongiform encephalopathy similar to BSE) in elk and deer in the western United States and Canada highlight the importance of research on wildlife and ecosystem health.

The contributions of veterinary research to the control of animal disease threats to human health, to the health and production of food animals, to the health of companion animals, to the advancement of biomedical sciences, and to the conservation of wildlife were reviewed in the Pew report Future Directions of Veterinary Medicine (Pritchard 1989). Other reports highlight the importance of veterinary research for countering agricultural bioterrorism (Countering Agricultural Bioterrorism, NRC 2003a), preventing the emergence of zoonotic diseases (The Emergence of Zoonotic Diseases: Understanding the Impact on Animal and Human Health, NRC 2002a), and preventing animal diseases (Emerging Animal Diseases: Global Markets, Global Safety, NRC 2002b). Despite the effect of veterinary research on animal and human welfare, support for it appears to be dispersed and inadequate as noted in the Pew report (Pritchard 1989). Schwabe (1984) points out that support for veterinary research tends to “fall between the chairs” and is not commensurate with its overall societal contribution. He further states that “improved human health is the single major social benefit that does

result either directly or indirectly not only from veterinary research on farm animals but from virtually all other activities of the veterinary profession, no matter what other needs they may serve simultaneously” (p. 13). In 1998, the National Research Council released a report that addressed the role of NCRR in supporting models for biomedical research and their related infrastructure (NRC 1998a). In 2004, the National Research Council released another report that examined the veterinary workforce for comparative medicine and provided strategies for recruiting veterinarians into careers in biomedical research (NRC 2004a). However, those reports limited their scope to biomedical sciences. An overall review of past and current veterinary research in public health and food safety, animal health, and comparative medicine and of projections of research directions could help to identify infrastructure and manpower needs, the adequacies and deficiencies in research effort, and a strategy for using the available resources effectively to meet societal needs.

Past and future trends and gaps in topics considered, scientific expertise required, current funding levels and sources, and institutional capacity were identified on the basis of a review of published literature—including the Pew report and the National Research Council reports cited earlier—and other data. The committee also hosted a community workshop (see Appendix C for the agenda) to solicit input from researchers and stakeholders in veterinary science. The committee defined national needs for future research in the three fields of veterinary science; assessed the adequacy of our national capacity, mechanisms, and infrastructure to support the needed research; and made recommendations for meeting the needs.

THE STRUCTURE OF THIS REPORT

This report provides an overview of past and current research in the three disciplines and the progress and opportunities in veterinary research in Chapter 2. The intent is not to conduct an exhaustive review of all the research activities in veterinary science; they have been documented elsewhere. Rather, Chapter 2 highlights the successes, describes some of the pressing contemporary issues in veterinary research, and identifies research and knowledge that are critical if future societal needs are to be met. A research agenda, with short- and long-term goals, needed to fill the knowledge gap is outlined in Chapter 3 based on selected critical research needs. Some strategies to achieve the research agenda were suggested, including infrastructure, expertise, manpower, and education. Chapter 4 describes the major resources and infrastructure available for veterinary research at colleges of veterinary medicine and colleges of agriculture and those provided by different agencies, institutions, and organizations. Chapter 5 assesses whether the available resources and infrastructure could meet projected needs in veterinary research.