4

Resources for Veterinary Research

Veterinary research takes place in many venues and is supported by varied agencies, foundations, companies, and donors. Much of the research in veterinary science takes place in academic institutions, such as schools and colleges of veterinary medicine, agriculture, medicine, and biology. Research on diseases of food-producing animals, including poultry, occurs also in the US Department of Agriculture, Agriculture Research Service (ARS). Other entities include private industries, especially those committed to animal health and nutrition, and the medical pharmaceutical industry.

Support for research comes from several federal agencies, such as the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and USDA; state governments; private foundations; public and privately held companies; and academic institutions. Some federal agencies support research through internal research programs and extramural research grants to investigators in academic institutions and other research organizations. USDA is especially noteworthy because it has a large internal research program in ARS and provides extramural research support via the Cooperative State Research, Education and Extension System (CSREES). To a lesser extent, NIH, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the Department of Defense (DOD), and other federal agencies also have both internal and external research programs in veterinary science.

This chapter reviews the research capacity—such as infrastructure, expertise, human resources, education, and financial resources—that has been built for veterinary science at universities, zoological parks, government agencies, and some other institutions.

OVERARCHING RESOURCES

The USDA CSREES maintains the Current Research Information System (CRIS), which compiles information on all funding sources used in agriculture, including those for such broad fields as animal systems and animal health and protection. USDA research agencies, state agricultural experiment stations (SAESs), state land-grant colleges and universities, state schools of forestry, cooperating schools and colleges of veterinary medicine, and USDA grant recipients at other institutions contribute information to CRIS. In 2003, research funding for animal systems (RPA 301-315) was close to $1 billion: the largest contributors of funding were the states and USDA (Table 4-1). However, the greatest

TABLE 4-1 Source of Funds for Animal Systems Research in FY 1998-2003 as reported by Current Research Information System for 15 Fieldsa

|

Source |

Funds (thousands) |

|||||

|

Fiscal Year |

||||||

|

1998 |

1999 |

2000 |

2001 |

2002 |

2003 |

|

|

USDAb |

$104,760 |

$117,121 |

$122,219 |

$133,855 |

$144,408 |

$152,445 |

|

Other USDAc |

10,682 |

11,004 |

12,970 |

18,856 |

22,878 |

23,713 |

|

CSREES ADMd |

77,336 |

74,978 |

79,088 |

83,637 |

87,178 |

91,870 |

|

State funds |

289,771 |

302,520 |

304,970 |

315,566 |

296,144 |

299,943 |

|

Other nonfederale |

160,103 |

151,063 |

167,922 |

180,900 |

187,261 |

197,655 |

|

Other federalf |

110,999 |

151,320 |

156,458 |

181,552 |

219,499 |

232,644 |

|

Total |

$753,651 |

$808,007 |

$843,627 |

$914,366 |

$957,368 |

$998,270 |

|

aCRIS reporting categories RPA 301-315 (reproduction, nutrition, genetics, animal genome, animal physiology, environmental stress, animal production and management, improved animal products, animal disease, external parasites and pests, internal parasites, toxicology, and animal welfare). bUSDA: regular USDA appropriations used for inhouse research by USDA research agencies and centers (excludes CSREES programs). (Form AD-418 field 131) cOther USDA: expenditure of funds received by SAESs and other cooperating institutions from contracts, grants, or cooperative agreement with one of the USDA research agencies other than CSREES. Identification of awarding agency is not collected. (Form AD-419 field number 219) dCSREES ADM: expenditure of formula and grant funds administered by CSREES and distributed to SAESs and other cooperating institutions (OCIs). Programs included are National Research Initiative, Hatch, McIntire-Stennis, Evans-Allen, Animal Health, Special Grants, Competitive Grants, Small Business Innovation Research Grants, and other CSREES grant programs. (Form AD-419 field 31) eOther nonfederal: expenditures by USDA agencies, SAESs, and OCIs of funds received from sources outside federal government, such as industry grants and sale of products (self-generated). fOther federal: expenditures by USDA agencies, SAESs and OCIs of funds received from federal sources outside USDA through contracts, grants, and cooperative agreements directly with other federal agencies. Sponsoring agencies may include National Science Foundation, Department of Energy, DOD, Agency for International Development, NIH, Public Health Service, Department of Health and Human Services, National Aeronautics and Space Administration, and Tennessee Valley Authority. (Form AD-418 field number 332 / Form AD-419 field number 332 minus field 219) SOURCE: USDA-CSREES. |

||||||

TABLE 4-2 Funding of Research in FY 1999-2003 for Animal Systems, Food Safety, and Zoonoses as Reported by Current Research Information System

|

Code and Research Subject |

1999 |

2000 |

2001 |

2002 |

2003 |

|

301 Reproductive performance |

$86,055 |

$85,758 |

$87,737 |

$90,751 |

$94,219 |

|

302 Nutrient use |

80,981 |

88,822 |

97,706 |

98,526 |

94,129 |

|

303 Genetic improvement |

49,031 |

49,082 |

51,930 |

55,018 |

60,459 |

|

304 Animal genome |

16,088 |

26,268 |

26,417 |

37,081 |

46,778 |

|

305 Animal physiology |

118,314 |

118,220 |

131,177 |

139,370 |

143,077 |

|

306 Environmental stress |

18,460 |

19,615 |

18,943 |

17,879 |

20,042 |

|

|

368,929 |

387,765 |

413,910 |

438,625 |

458,704 |

|

311 Animal disease |

302,338 |

313,703 |

348,745 |

369,125 |

379,650 |

|

312, 313 Parasites |

33,037 |

34,362 |

34,283 |

36,657 |

36,594 |

|

314 Toxicology |

24,836 |

23,926 |

25,886 |

26,348 |

31,472 |

|

315 Animal welfare |

12,371 |

13,067 |

13,921 |

14,812 |

16,799 |

|

|

372,582 |

385,058 |

422,835 |

446,942 |

464,515 |

|

711 Food-product safety |

16,228 |

13,689 |

15,769 |

19,321 |

22,630 |

|

712 Preventing food contamination |

90,907 |

107,383 |

122,639 |

134,015 |

145,095 |

|

721 Insects and pests |

19,774 |

20,615 |

22,783 |

25,648 |

27,740 |

|

722 Zoonotic diseases and parasites |

7,090 |

8,220 |

9,705 |

10,550 |

14,350 |

|

723 Hazards to human health |

17,178 |

18,743 |

23,269 |

29,709 |

37.186 |

|

|

151,177 |

168,659 |

194,165 |

219,243 |

247,001 |

|

SOURCE: USDA CSRESS CRIS. |

|||||

increase in funding (109%) from 1998 to 2003 was in the other federal category, and this indicates the growing importance of animal health research as it affects public health, bioterrorism mitigation, such basic science fields as ecology, laboratory animal medicine, and other nonagricultural fields of research.

The $1 billion of funding in animal systems includes fields other than animal health and protection. Closer analysis suggests that direct funding for diseases, their agents, and their effects (RPA 311-315) is at a much lower level of $464 million and includes cross-cutting areas of zoonoses. Food safety accounts for an additional $247 million (Table 4-2). However, any of those three funding levels are lower than what is needed to solve animal health and protection problems.

SCHOOLS AND COLLEGES OF VETERINARY MEDICINE

There are 28 schools and colleges of veterinary medicine (CVMs) in the United States. Almost all are parts of major land-grant universities. The first CVM was founded in 1877, the youngest was founded in 1998 and admitted its first class in 2003. Because the youngest has been operating for less than 2 years, it was omitted from many of the resource analyses in the following sections.

The mission of all every CVM includes teaching the art and science of veterinary medicine to professional students: providing postgraduate education

for graduate students, interns, residents, and practicing veterinarians; and advancing veterinary research. The CVMs operate teaching hospitals to provide clinical education for their professional students and referral resources for the practicing veterinary community. Many also operate field patient-care units to serve farms and ranches. Research is an important component of CVMs and is included as one of the points of evaluation in the accreditation process (AVMA, 2004b). The CVMs conduct much of the academically based veterinary research in the United States.

Facilities and Infrastructure

Facilities and infrastructure related to research in CVMs consist of buildings for classrooms, research laboratories, offices, and the like: barns and pastures; non-CVM support laboratories, such as laboratory animal facilities and central research service laboratories; libraries; diagnostic laboratories; and a variety of CVM and campus-based information-technology resources, such as super computers and electronic information management and exchange. Some CVMs have access to other, specialized research-support infrastructure, such as unique databases, computerized patient-record systems, and banks of specialized research materials (for example, tissue banks).

Libraries constitute an important resource for veterinary research. Libraries range from large collections, such as the National Agricultural Library and the National Library of Medicine, to small collections in individual departments. Every university, many schools and colleges, many departments, and essentially all other research venues, such as research institutes and industry, have libraries. Collections can number in the millions and often extend back many decades or even several centuries. Those collections set new research into proper historical context and help to avoid duplication of work. In addition to collections of books and periodicals, all research libraries nowadays have electronic search capabilities and large collections of electronic data and publications. Librarians who are well trained and experienced in both conventional and electronic literature searches can develop extremely useful searches not only of the traditional peer-reviewed scientific literature, but also of Web sites and other on-line information sources that are invaluable in many research projects. Libraries are sometimes overlooked when funds for research resources and infrastructure are allocated.

Estimating the size and adequacy of the facility infrastructure available to CVMs for research is difficult because some resources are not devoted solely to veterinary research. CVMs engage in multiple activities in addition to research, including teaching of professional students, clinical patient care, and diagnostic services. Perhaps because of the difficulty in defining resources dedicated to veterinary research, there is no centralized source of information on the size of the infrastructure of CVMs. Moreover, much of the research infrastructure listed above may be shared with other, nonveterinary research activities. For example,

libraries, animal housing, research laboratories and centralized facilities for such activities as electron microscopy, molecular sequencing, electronic data management, and statistical analyses are often shared with faculty outside the CVMs.

There seem to be no data on the amount of research space available in CVMs. The only relevant data the committee could locate are in a survey conducted by the Association of American Veterinary Medical Colleges (AAVMC). CVMs were asked to identify their needs for space and equipment to train an additional 241 veterinary students and 658 new graduate students (AAVMC, 2004). The results of the survey are summarized in Table 4-3. Separating infrastructure devoted to professional-student instruction from that for research is difficult. Although some facilities, such as classrooms, are used mostly for professional-student instruction, they also are often used for graduate-student instruction, research symposiums, and seminars. The same holds for teaching laboratories. CVMs reported that about 400 new faculty persons and about 2.25 million square feet of new and renovated research space would be needed for education and training of additional veterinary and graduate students.

Laboratory equipment is another major category of research infrastructure, and obtaining data on this category is even more problematic. The best figure obtained was from the AAVMC survey of CVMs (AAVMC, 2004), which reported the need for about $37 million in one-time funds for equipment. The proportion of the proposed new equipment funds allocated for research is not known, and the numbers do not show the total amount, condition, or value of research equipment now available in CVMs.

Every CVM provides some level of patient care as part of its clinical teaching program, and some CVMs have large patient populations, including access to large numbers of farm animals and horses through a variety of outreach programs (Table 4-4). Collectively, CVMs have over 10 million animal patients or patient visits a year (Table 4-4). However, not all patients are suitable for research programs, and owner consent is required.

Clinical records can be useful resources if they are archived properly and kept in a uniform format that allows comparison and analysis. However, teaching

TABLE 4-3 Infrastructure Needed for Colleges of Veterinary Medicine to Support 241 Additional Veterinary Students and 658 New Graduate Students

|

Category |

New (gross square feet) |

Renovated (gross square feet) |

|

Classrooms |

165,197 |

79,392 |

|

Teaching laboratories |

188,714 |

106,932 |

|

Research laboratories |

656,662 |

309,085 |

|

Faculty offices |

147,216 |

44,086 |

|

BSL-3 laboratories |

146,454 |

12,456 |

|

BSL-3 animal housing |

336,743 |

58,700 |

|

Totals |

1,640,986 |

610,651 |

|

SOURCE: AAVMC member survey, 2004. |

||

TABLE 4-4 Total Patient Contacts by Faculty Members in All CVMs in 2002

|

|

Hospital Visits (Small Animal) or Animals Examined (Food Animals and Horses)a |

|||

|

Animals |

Mean |

Median |

Range |

Total, All CVMs |

|

Small animals |

12,700 |

12,000 |

4,500-27,700 |

354,500 |

|

Cattle |

14,000 |

11,600 |

2,300-62,000 |

439,500 |

|

Swine |

12,600 |

276 |

3-175,300 |

276,300 |

|

Horses |

3,400 |

2,000 |

7-16,220 |

88,300 |

|

Poultry |

342,000 |

353 |

2-8,152,000 |

8,890,000 |

|

aCVMs that did not examine animals of a given category were excluded in all cases. SOURCE: AAVMC, 2004. |

||||

hospitals commonly maintain paper or electronic records in formats that are not easily interchangeable or manipulated. With the exception of the Veterinary Medical Database (www.vet.purdue.edu/depts/prog/vmdb.html), there are no national databases and no centralized records for patients or data on patients—such as radiographs, clinical laboratory data, or necropsy or biopsy data—as far as the committee is aware. A number of repositories or collections of material are sometimes available for research. For example, the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology Department of Veterinary Pathology, housed at Walter Reed Army Medical Center in Washington, DC, maintains a large collection of lesions of domestic and some wild animals. The Registry of Tumors in Lower Animals is a collection of lower-vertebrate and invertebrate tumors at the George Washington University Medical Center in Washington, DC. Those collections can be considered as national databases because the centers accept material from the entire country and from around the world, but they do not represent the incidence or prevalence of diseases in domestic animals in the United States, because they rely on voluntary submissions.

There is a recent effort to make all the clinical records from a large private practice’s database available to the research community (Wiese, 2003). That is a commendable effort, but it is still in its early stages, and insufficient time has elapsed to see whether successful collaborations can be sustained and expanded. Nonetheless, the collaborative effort illustrates the potential power of data-sharing among CVMs and large private practices. Many changes need to occur before veterinary researchers can take full advantage of the relatively large numbers of patients seen by CVM faculty members, and even more effort will be needed to involve the private-practice sector in research. Adding public and private diagnostic laboratories would further enhance the research value of clinical data.

Some clinical research is conducted. Prospective and retrospective studies are carried out. Patients are entered into a variety of intrainstitutional or multicenter research protocols. Successful programs in which patients are screened for targeted diseases and entered into appropriate research programs have been main-

tained. Chemotherapy for malignant disease in small animals has been advanced greatly through multicenter trials (Vail et al., 1995). The multisite coordinated study of the so-called vaccine-site fibrosarcomas is another example of a successful clinically based research program (Morrison and Starr, 2001). Industry uses the unique expertise of CVM faculty and their access to patients to further the development of new and improved vaccines, pharmaceuticals, diets, and diagnostic tests. All those research and development projects could be enhanced and facilitated if there were more comprehensive national databases.

Expertise and Human Resources

A wide variety of both clinical and basic-science expertise is represented among about 2,665 full-time equivalent (FTE) faculty in the nation’s CVMs. The major research credential for veterinary researchers is the doctoral degree. In contrast with human-medicine researchers, who often prepare for research careers with non-degree-granting research fellowships, veterinary researchers are likely to have obtained advanced graduate degrees. Members of the clinical departments almost always have DVMs (or the equivalent). Most members have specialty certification, and many have master’s degrees. Veterinarians in basic-science departments are very likely to have PhDs and may or may not have specialty certification,1 depending on the subject-matter responsibilities of the department.

In addition, many members of CVM faculties do not have DVMs, but almost all such persons have PhDs or the equivalent. The committee could not obtain quantitative data on the number of nonveterinary PhD scientists in the nation’s CVM faculties. The most recent data available are from the AAVMC Comparative Data Report for the academic year 1995-1996. The report shows that the 27 CVMs in existence at that time had a total of 2,303 faculty members (assistant professors and above), of whom 479 (21%), including 10 administrators, had PhDs without DVMs. On the basis of that information and the experience of many committee members with faculties of CVMs, the committee estimated that scientists with PhD degrees but without DVM degrees now constitute 20-35% of most CVM faculties, that is, about 530-930 FTEs nationwide. The majority of those scientists work in basic-science departments, and many engage in research. Indeed, nonveterinary PhD scientists form the heart of many basic-science research programs in many CVMs. About 25% of the full-time faculty of the nation’s schools and colleges of medicine have PhDs, or other health doctorates

such as in dentistry or veterinary medicine—without MDs (AAMC, 2001; AAVMC 2004.)

Among the 2,665 FTE faculty in the nation’s CVMs, about 130 are administrators. The faculty receive some assistance, either with teaching or clinical patient care, from interns (about 177), nonclinical residents (about 70), and clinical residents (about 600), but interns and residents require supervision and assistance from faculty. Graduate students and postdoctoral researchers also contribute to the research programs and require supervision, assistance, and mentoring.

The committee attempted to estimate how much time, on the average, faculty have for research, as opposed to formal teaching, patient care, student advising, committee work, and other professional commitments that make up academic life. Even when one includes as “research time” such important activities as informal teaching of graduate students and postdoctoral researchers in laboratories, journal clubs, seminars, research discussions and the like, it is unlikely that the estimated 2,665 FTE faculty have more than 50% of their time, on average, to devote to research. That suggests that the entire country has perhaps about 1,300 FTE faculty in schools and colleges of veterinary medicine available to conduct research in veterinary science. Given the heavy teaching and patient-care loads of many faculty (the veterinary student:faculty ratio is about 3.6:1 compared with the medical student:faculty ratio of about 0.63:1), the committee believes that, on the average, veterinary faculty have considerably less than 50% of their time available for research.

Postdoctoral fellows also contribute substantially to research in CVMs. They bring their scientific experience and ideas and provide laboratory support for faculty, who have competing demands. Most postdoctoral fellows are supported by individual investigators’ research grants (Singer, 2004). Postdoctoral fellows as a human resource in CVMs cannot be quantified, because data are not available.

Education

A primary mission of all CVMs is education. In addition to educating students to become doctors of veterinary medicine, CVMs educate interns and residents, graduate students and postdoctoral fellows, and often undergraduate students. Some CVMs have large degree-granting undergraduate programs that are independent of the professional programs and have hundreds or thousands of enrollees. Continuing professional education for veterinarians and public outreach via extension or client education are provided by all CVMs. CVMs also serve as a general resource for the community for a broad variety of topics related to animals. Education of the scientific community via presentations at scientific meetings and publications in refereed literature is a fundamental responsibility of veterinary researchers.

In 2003, 28 CVMs in the United States reported an enrollment of 9,587 students (2,270 men and 7,317 women) in the professional veterinary medical-

education programs leading to the DVM or VMD degree (AAVMC, 2003a; Appendix F). Of those, 2,308 were enrolled in the fourth year and thus expected to graduate in spring 2003, which is comparable with the numbers of graduates in the past several years. From 1995 to 2004, the number of professional students enrolled in CVMs increased by 733 and the number of full-time equivalent faculty increased by 448. Student/faculty ratio has remained steady at about 3.5 since 2001 (Appendix F). In the 2003 AAVMC report, CVMs reported graduating 1,882 students with bachelor of science (BSc) degrees,2 315 with master of science (MSc) degrees, and 284 doctor of philosophy (PhD) degrees. The committee is not aware of any sources of the numbers of students enrolled in degree-granting programs other than the professional and graduate curricula.

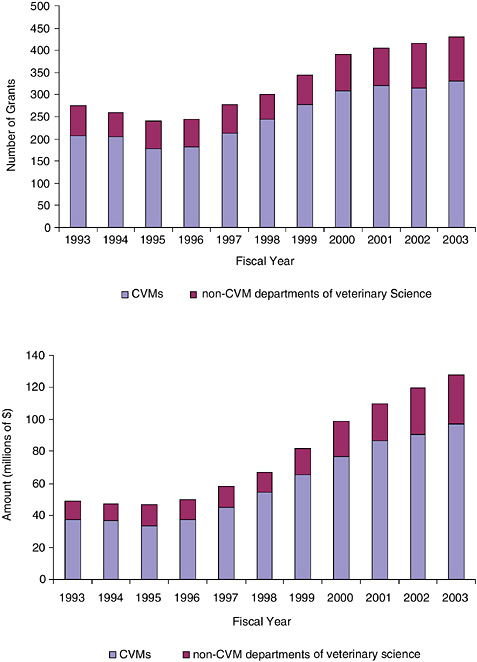

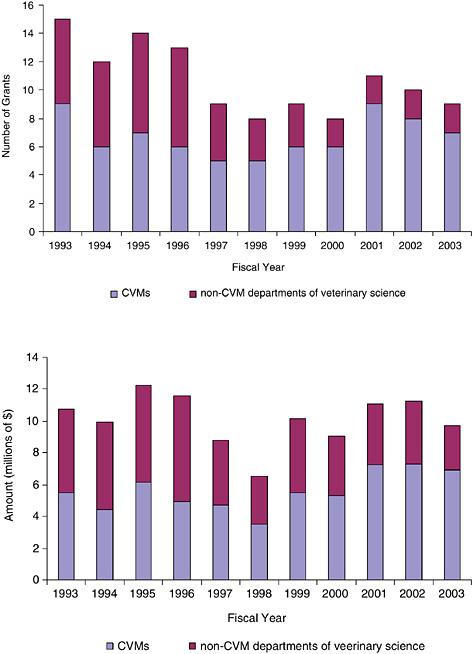

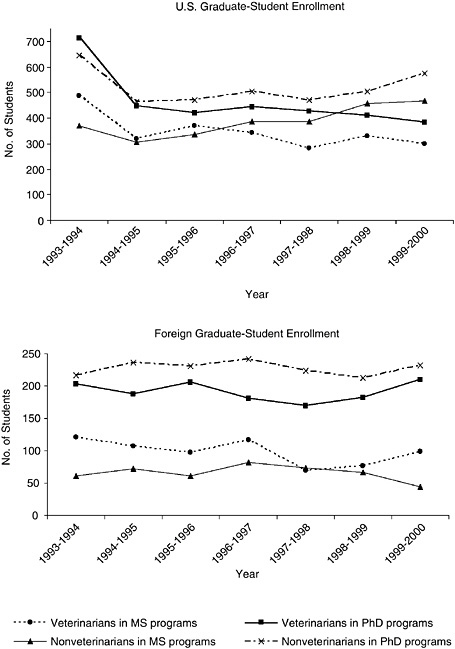

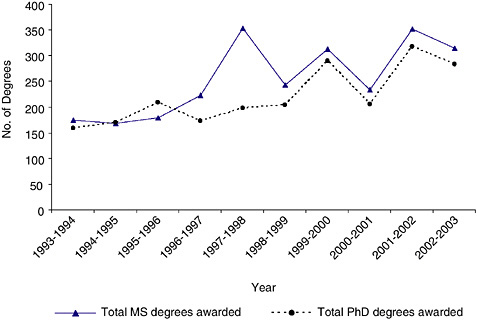

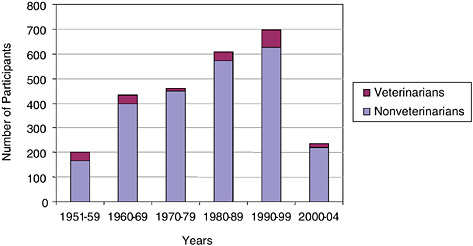

Figures 4-1 and 4-2 show the data on graduate enrollment in CVMs in 1993 to 2000 and graduate degrees awarded in 1993 to 2003. (Data on enrollment are not available beyond 2000.) The number of US veterinarians and nonveterinarians enrolled in MS and PhD programs declined from 1993-1994 to 1994-1995 for unknown reasons. After that, enrollment in graduate programs remained steady, with a slight upward trend in non-DVMs and a slight downward trend in DVMs enrolled in MS and PhD programs. The enrollment numbers for foreign students remained more or less constant (Figure. 4-2). Foreign students constitute 31-35% of PhD students enrolled in CVMs. With the exception of 1996-1997, the number of PhD degrees awarded to US and foreign students increased, albeit somewhat irregularly, from 159 in 1993-1994 to a high of 318 in 2001-2002, followed by a decline to 284 in 2002-2003. The number of MS graduates followed a similar pattern (Figure 4-2). The gradual rise in the number of PhDs awarded coupled with decreases in DVMs seeking PhDs and the increase in non-DVMs enrolled in PhD programs suggests that fewer DVMs are earning PhDs now than a decade ago (Freeman, 2005; NRC, 2004b).

Because of the length of time required and the attendant costs, most veterinarians do not continue their research education with postdoctoral experience. In contrast, researchers who are nonveterinarians commonly spend 2 years or more as postdoctoral fellows. Typically, veterinarians can expect to spend 3-4 years in a general undergraduate curriculum, 4 years in a school or college of veterinary medicine, and 4-5 years to obtain a PhD. The time for postgraduate training may also include preparation for a specialty certification. Those who do not obtain DVMs can go directly from undergraduate to graduate programs and may then pursue postdoctoral training. Thus, the time required for a veterinarian to obtain a DVM and a PhD is comparable with the time required for a nonveterinarian to obtain a PhD plus postdoctoral training. However, the cost to the person may differ substantially because the high tuition fees of veterinary school are rarely

FIGURE 4-1 Number of US and foreign graduate students enrolled in colleges of veterinary medicine in the United States, 1993-2000. Veterinarians (DVMs) in MS and PhD programs include those with or without concurrent enrollment in residency programs. SOURCE: Association of American Veterinary Medical Colleges.

FIGURE 4-2 Number of MS and PhD degrees awarded to US and foreign students by colleges of veterinary medicine in the United States, 1993–2003. SOURCE: Association of American Veterinary Medical Colleges.

offset by scholarships or training stipends. Most veterinarians and nonveterinarians obtain at least partial financial support for graduate and postdoctoral training. Veterinarians often find themselves facing substantial debt at the end of graduate school. Many opt to enter their research careers directly instead of pursuing postdoctoral training, which allows a scientist to mature and become an independent investigator. A postdoctoral researcher has an opportunity to get research experience as a semiautonomous investigator, obtain a research grant relatively independently, and perhaps most important, establish a network of contacts and collaborators that often lasts throughout one’s career. In fact, many believe that the major debt owed by veterinarians at the end of the professional curriculum is a substantial deterrent to their even considering graduate education (Freeman, 2005). The mean educational debt of 2004 graduates reporting debt was $81,052, and 76.9% of new graduates had incurred debt of $40,000 or more. Some 91% of the mean debt of 2004 graduating veterinarians was incurred while they were enrolled in CVMs (Shepherd, 2004).

In 2004, 1,814 (81.5%) of 2,225 new graduates of 26 of the 27 CVMs responded to an American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA) survey about their employment and career choices. Among the 1,391 respondents who answered the question, 358 (25.7%) were entering advanced-study programs (Shep-

TABLE 4-5 NIH Training Awards to CVMs

|

Award Categorya |

1993 |

2003 |

||

|

Number of Awards |

Amount (millions) |

Number of Awards |

Amount (millions) |

|

|

F |

42 |

$1.1 |

38 |

$1.5 |

|

K08 |

2 |

0.2 |

39 |

4.1 |

|

T32 |

19 |

2.2 |

33 |

6.8 |

|

T35 |

5 |

0.2 |

11 |

0.7 |

|

T37 |

7 |

1.5 |

0 |

0 |

|

aF = fellowship awards, including F08, individual national research service awards K08 = clinical investigator awards T32 = institutional national research service award T35 = short-term training T37 = minority international research training grants SOURCE: NIH Office of the Director. |

||||

herd 2004), but it is unclear how many were pursuing graduate studies in CVMs. The total number of interns and residents employed by CVMs in 2002 was reported to be about 845. Although the duration of most internships is 1 year, most residencies last longer than 1 year. Furthermore, not all newly employed interns and residents are new graduates of professional programs. Because current data on the total number of graduate students enrolled in CVMs and the number of veterinarians seeking graduate degrees or nondegree research training outside CVMs are not available, the committee cannot accurately estimate the number of veterinarians actively preparing for research careers in CVMs.

There are very few data on sources of support for graduate students in CVMs. Schools and colleges provide some internal funds as stipends, scholarships, or paid tuition, but many students pay part or all of their educational expenses. A variety of organizations—such as USDA, the military, and CDC—have grants and other mechanisms for supporting graduate education for veterinarians. NIH provides a number of awards for support of advanced training (Grieder and Whitehair, 2005), some of which go to CVMs (Table 4-5). K08 awards to veterinarians affiliated with CVMs increased from two in 1993 to 39 in 2003—a factor of almost 20. K08 awards to all recipients in the same period increased by about 86% (data not shown).

Financial Resources for Research

In 2002-2003, CVMs reported total research expenditures of $321.2 million on a total of 5,794 research awards (Table 4-6). Of those, 1,247 were from the Department of Health and Human Services (mostly from NIH), with expenditures totaling $155.6 million. Data from NIH for 2003 show 590 awards (in all

TABLE 4-6 Research Expenditures in Colleges of Veterinary Medicine, FY 2002-2003

|

Funding Sourcea |

Amount (millions)b |

Number of Awards |

|

NIH, FDA, and CDC |

$155.6c |

1,247 |

|

USDA |

34.4 |

595 |

|

DOD |

5.9 |

53 |

|

EPA |

1.8 |

31 |

|

NASA |

2.6 |

24 |

|

NSF |

3.5 |

48 |

|

DOI |

0.8 |

34 |

|

Other Federal Agencies |

7.6 |

116 |

|

State Agencies |

38.8 |

558 |

|

Industry |

25.2 |

942 |

|

Private |

30.4 |

1,291 |

|

Other |

14.6 |

855 |

|

Totals |

$321.20 |

5,794 |

|

aFDA=Food and Drug Administration, EPA=Environmental Protection Agency, NASA=National Aeronautics and Space Administration, NSF=National Science Foundation, DOI-Department of the Interior. bIncluding indirect costs if applicable. cAbout $154 million from NIH. SOURCE: AAVMC, 2004. |

||

categories except contracts) totaling about $181 million to investigators in CVMs. The discrepancy between the two figures can be explained by the fact that the CVMs and NIH fiscal years are different and NIH reports amount awarded, whereas the CVMs report amount expended. About 200 of the NIH awards (worth about $63 million) were to veterinarians, so about 390 awards valued at about $118 million went to nonveterinarians in CVMs.

All faculty in CVMs (including veterinarians and nonveterinarians) were awarded 331 R01 grants from NIH in 2003 with a total value of $97 million. On the average, each FTE accounted for 0.124 R01 award with an average value of about $36,500. In comparison, all faculty in colleges of medicine obtained 0.148 R01 award per FTE with an average value of about $50,000 in 2003. That suggests that CVM faculty members are competitive at the highest level, especially in light of the average student:faculty ratio in CVMs of 3.6:1 compared with 0.6:1 in colleges of medicine. The accomplishments of CVM faculty also are impressive in that the 5,794 research awards totaling $321 million in research expenditures were obtained by 2,665 CVM FTEs, most of whom spend less than 50% of their time on research.

The number of awards and amount of funding from NIH dominate, reflecting the importance of comparative medicine in veterinary research and the relatively large extramural research budget of NIH. Data from NIH show that veterinarians affiliated with CVMs received 134 awards in all categories (excluding contracts)

in 1993 with a value of $25 million.3 By 2003, the number of awards had increased to 197 with a value of $63 million. When all NIH awards (excluding contracts) to all investigators affiliated with CVMs are considered, the numbers in 1993 were 407 awards and $67 million, and those for 2003 590 and $180 million. The data indicate that veterinarians account for about one-third of the awards and 35% of the funds awarded to CVMs by NIH in 2003, a slight improvement from the roughly 27% of the funding to veterinarians in 1993. The data also emphasize the importance of the nonveterinary PhD scientists to the research programs of CVMs. Given that those scientists constitute 20-35% of the CVM faculty FTEs, it follows that about one-fifth to one-third of the CVM faculty account for about two-thirds of the research funds from NIH.

Table 4-7 shows another breakdown of awards from NIH from FY 1997 to FY 2001, when the NIH budget doubled. (FY 2003 awards are included to evaluate whether increases have been sustained.) The number of awards to veterinarians in CVMs increased at about the same percentage as did those to all investigators. When both veterinarians and nonveterinary investigators in CVMs are taken together, the percentage increase for R01 awards was considerably higher than that of all investigators. Nonveterinarians were responsible for 74% to 81% of all R01 awards to CVMs in each of the years shown.

USDA is not the second-largest source of extramural research expenditures, but rather the third, being exceeded by the state. At least one CVM includes state funding for a large diagnostic laboratory in its total of state funds for research, and others may do so as well. Therefore, the expenditures of state funds for research, as opposed to diagnostic laboratory activities (granted that some of these activities may be research) may be overstated. When those two sources are grouped, the number of awards (1,153) is about the same as the number from the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) (1,247), but the amount of funding is less than half ($155 million from DHHS and $73.2 from USDA plus state sources). Funds from USDA and some state funds support projects relevant to agriculture (including horses), but the amounts seem small, considering that the US food and fiber industry generates over $200 billion a year in farm cash receipts (USDA, 2003). Disease costs the livestock industry and consumers about $1 billion a year (USAHA, 2004).

Funding to CVMs from industry and private sources is comparable with that from USDA. The number of awards from private sources slightly exceeds the number from DHHS and from industry. The relatively large number of awards suggests that the small awards seem to be needed to address significant voids in available public funding, such as support for research on diseases of pet or exotic animals.

Table 4-8 shows CVMs sorted into quartiles by faculty FTE size and student: faculty ratios in FY 2002. (See Appendix G for CVMs sorted into quartiles by

TABLE 4-7 NIH Awards to Veterinarians and CVMs

research expenditures from different sources.) CVMs with fewer faculty FTEs not only have smaller total research expenditures but also have lower research funds expended per individual when averaged over the entire faculty. Furthermore, the student:faculty ratios are considerably higher in the CVMs in the first than in the fourth quartile. As faculty size (FTEs) increases and student:faculty ratios decrease, total research funds and average research funds per faculty FTE increase. Average funds from all sources per faculty FTE doubles from the smallest to the largest faculty quartile and the total funds increase by a factor of almost 5. Those data may be explained in part by the fact that CVMs and their home universities vary in their approaches and missions: some emphasize research much more than others. Moreover, some CVMs have severe limitations on physical facilities, faculty expertise, and other resources required for research.

The data also suggest that the number of faculty FTEs must reach a “critical mass” for faculty to spend more time on research and compete for funds effectively. That viewpoint is supported by the fact that the student:faculty ratio of the CVMs in the first quartile (4.80:1) is about 62% higher than the ratio in the fourth quartile (2.97:1). Average research funding per faculty FTE from NIH, USDA, states, industry, and all sources increases dramatically in the third and fourth quartiles as faculty FTEs exceed 100 and student:faculty ratios decrease to 3.8:1 and lower (Table 4-8). The impact of critical mass extends even to research funded by a CVM’s home state, where research funds per faculty FTE in the fourth quartile are almost 6 times as high as in the first quartile.

TABLE 4-8 FY 2002 CVMs Sorted into Quartiles based on Faculty Size (full-time equivalents—FTE). The average faculty FTE size, student/faculty ratio, and average research expenditures from USDA, state, industry, private sources and NIH by CVMs in each quartile are reported.

|

|

|

1st Quartilea |

2nd Quartilea |

3rd Quartilea |

4th Quartilea |

|

Average Faculty FTEs |

60 |

82 |

101 |

143 |

|

|

Average Student:Faculty Ratio |

4.80:1 |

3.64:1 |

3.83:1 |

2.97:1 |

|

|

USDA |

Average amountb |

$391,839 |

$914,477 |

$1,629,066 |

$2,168,747 |

|

|

Amount per faculty FTE |

$6,483 |

$11,201 |

$16,201 |

$15,179 |

|

States |

Average amountb |

$264,982 |

$409,678 |

$1,263,677 |

$3,648,673 |

|

|

Amount per faculty FTE |

$4,384 |

$5,018 |

$12,568 |

$25,538 |

|

Industry |

Average amountb |

$448,575 |

$398,274 |

$1,263,584 |

$1,552,710 |

|

|

Amount per faculty FTE |

$7,422 |

$4,879 |

$12,567 |

$10,868 |

|

Private |

Average amountb |

$302,671 |

$1,155,759 |

$576,094 |

$2,353,134 |

|

|

Amount per faculty FTE |

$5,008 |

$14,157 |

$5,739 |

$16,470 |

|

NIH |

Average amountb |

$2,447,974 |

$3,267,116 |

$5,252,496 |

$11,413,416 |

|

|

Amount per faculty FTE |

$40,503 |

$40,020 |

$52,238 |

$79,886 |

|

TOTAL ALL |

Average amountb |

$4,845,384 |

$7,390,228 |

$11,443,605 |

$22,905,480 |

|

SOURCESc |

Amount per faculty FTE |

$80,169 |

$90,525 |

$113,812 |

$160,322 |

|

aFirst quartile is composed of six CVMs; the others seven CVMs. One CVM in existence less than 2 years was omitted. bAverage amount is average research expenditure per CVM in each quartile for funding source shown. cTotal all sources includes some sources not shown in table. |

|||||

Amounts of research funds obtained by CVMs do not depend solely on increasing faculty size, as shown by the three pairs of CVMs with the largest total research expenditures. When the six CVMS with the largest total research expenditures were paired up on the basis of similar total research expenditures, we found that in each of the three pairs, the college with the fewer faculty FTEs had more research dollars per FTE. Differences ranged from $50,000 to nearly $150,000 in average research expenditure per FTE. In all but one pair, student: faculty ratios were nearly identical. In the one where differences occurred, the school with the higher student:faculty ratio had the larger amount of research funds per FTE, although the total amount of research funds was smaller. (Data not shown.)

Another element that may influence the amount of funds received by CVMs is the presence or absence of other facilities with relevant programs, such as a college of medicine (CoM) or a USDA ARS research laboratory on the same campus or nearby. The presence of such facilities does not itself result in more campus resources for research in biomedicine, nor does it mean that CVMs have access to more or better physical resources or collaborative opportunities. Nevertheless, it is reasonable to assume that the presence of additional biomedical or agricultural research programs may have some favorable influence on the research climate that may be reflected in the research expenditures of CVMs. The committee examined data on CVMs that had CoMs on the same campuses and on CVMs that had USDA ARS laboratories on or near the campuses, and on CVMs that had neither. (See Appendix H for details of the analysis.) CVMs at universities that CoMs that were not on the same campuses were excluded from the analysis. The main findings are as follows.

-

Of the 27 CVMs studied, 10 CVMs have co-located CoMs, and three of the 10 also have ARS laboratories nearby. The 10 reported about 46% of the research expenditures by all 27 CVMs from NIH, 44% from USDA, and 47% from all sources.

-

Two groups of six CVMs each with similar faculty size (but different student:faculty ratios) were selected for comparison on the basis of the presence or absence of a co-located CoM. The group of six with co-located CoMs reported about twice the research expenditures from NIH and from all sources of the group of six without CoMs.

-

Nine CVMs were selected because they each have an ARS laboratory nearby. (Three of the nine also have co-located CoMs.) The nine account for about 50% of the research expenditures from USDA even though they amount to only one-third of the CVMs.

-

Two groups of four CVMs each with comparable faculty sizes (but different student:faculty ratios) and no co-located CoMs were compared. One group of four had ARS laboratories nearby, and the other group of four did not. The former group reported about twice the research expenditures per faculty FTE from USDA of the latter group.

Those and the previous data do not establish size (faculty FTEs), student: faculty ratio, and the presence of additional research programs as causative factors in determining whether some CVMs obtain more research funds than others. They do, however, suggest that critical mass and campus research environments play a role in the relative research funding of CVMs. Although data were not available for analyses, favorable research environments may include the presence of schools of public health, integrated shared research resources, and other research-oriented programs. The larger amounts of research funding in CVMs co-located with research facilities of other related disciplines suggest that those CVMs may benefit from collaborative interdisciplinary research with those facilities. In fact, the CVM with the largest reported expenditures from NIH and all sources has a large CDC laboratory and several other federal research laboratories on or adjacent to the campus even though it is not co-located with a CoM or an ARS laboratory. That CVM also has a large faculty and a low student:faculty ratio.

COLLEGES OF AGRICULTURE

Colleges of agriculture in the United States are typically components of land-grant institutions. They contribute substantially to animal health research, particularly on diseases of production animals, and often through interaction with agencies of USDA. Colleges of agriculture vary in size, focus, and expertise in veterinary science. Among their diverse curricula and research programs, emphases that fall within veterinary science include animal science, agricultural and food biosecurity, agricultural systems, animals and animal production, biology, biotechnology and genomics, nutrition and health, natural resources and environment, and pest management. Other disciplines that contribute greatly to veterinary science include biochemistry, statistics, and information technology.

Infrastructure

Research facilities of land-grant universities include over 25 million square feet of laboratory and office space, about 885,860 acres of land, and about 3.56 million square feet of greenhouse space (USDA, 1999). Greenhouse space is used for studies of effects of poisonous plants on animals, for growing plants used for vaccines and nutritional research, and for entomology research. In colleges of agriculture, the facilities of several academic departments and units are directed toward research on some aspect of animal health or veterinary science, and those facilities should be considered in assessing current infrastructure. Furthermore, most colleges of agriculture have specialized interdepartmental technological units for electron microscopy, DNA development, transgenic animals, proteomics and so forth, and these units contribute in major ways to research in veterinary science. Animal housing facilities, which may be extensive in large departments

of animal science, rarely contain facilities for infectious-disease research in production animals. The following academic departments and units make particularly important contributions to veterinary science:

-

Departments of veterinary science. Most departments of veterinary science in colleges of agriculture, especially in states that do not have CVMs, have facilities dedicated to production-animal health research. Existing under various names, those departments have been funded by at least 12 states. Traditionally, financial and commodity-group support for veterinary science—although strong in some states—is less than in states that support 4-year CVMs. Research facilities, faculty, and funding are directed to disease, of livestock, poultry, and aquaculture and are mostly dedicated to state and local animal health problems. The largest share of funding is typically directed to infectious diseases of economic importance.

-

Departments of animal science. Departments of animal science traditionally contribute to research on the genetics, nutrition, physiology and metabolism, reproductive management, and toxicology of domestic food-producing animal species. Much of the research overlaps with animal health research. In the last decade, the role of animal science departments has expanded to include companion-animal physiology and behavior.

-

Departments of entomology. Major contributions to medical and veterinary science are made by entomologists in colleges of agriculture. For example, the transmission and infectivity cycle of West Nile virus was elucidated by medical entomologists who tracked patterns of infected mosquitoes that were similar to patterns of the disease in birds and mammals. Colleges of agriculture in major land grant institutions typically support insectaries, which are critical to successful research in veterinary entomology.

-

Departments of wildlife and fisheries. The movement of infectious diseases among domestic and wild mammals, birds, and aquatic species is a major concern of veterinary science. Furthermore, the interface between wildlife and domestic animals is of increasing importance and concern to the livestock industry. Academic departments and research facilities dedicated to wildlife, fisheries, and other ecological components exist in nearly all colleges of agriculture. Although the departments handle the obligations of wildlife biology, few play a substantial role in animal health problems in wildlife and fish. With few exceptions, their mission statements have narrow focus, lack the demands of extramural forces (such as commodity groups, industry, and National Park Service missions) to drive the research, and have inadequate training of faculty to handle cutting-edge approaches to infectious and noninfectious diseases of animals. In universities that also have CVMs, opportunities and facilities for cooperation are common. However, the facilities are typically inadequate to deal with wildlife disease or the wildlife-domestic animal disease interface seriously over an extended period.

-

State agricultural experiment stations. Funds from SAESs support research facilities in a wide variety of disciplines. The Hatch Experiment Station Act, passed by Congress in 1887, created a system of state agricultural experiment stations with the land-grant universities and provided a mechanism to channel federal funding to colleges of agriculture. In 1914, the Smith-Lever Act created the Cooperative Agricultural Extension Service as a partnership of county, state, and federal governments (Fuglie et al., 1996). Those acts and the Morrill acts were created to “deliver the benefits of scientific research and education in the colleges of agriculture to the public citizens to improve the economic viability and life of farmers and rural communities” (USDA, 1999).

Expertise and Human Resources

Much of the wide variety of animal research expertise available in colleges of agriculture applies to veterinary science and related animal health fields. Faculty members in colleges of agriculture participate as team members in research of high national importance—for example, departments of entomology and virology in research on West Nile virus disease and departments of economics, animal science, and chemistry in research on bovine spongiform encephalopathy in beef and dairy cattle.

In the last decade, brucellosis in bison and elk in the greater Yellowstone ecosystem (GYE) has been a focus of national attention. The persistence of brucellosis in the GYE (caused by Brucella abortus in elk and bison) and in marine mammals (caused by Brucella spp. in dolphins, seals, whales, and others) in the face of the elimination of this disease from domestic animals requires a substantial research program plan (NRC, 1998b). The formation of the Greater Yellowstone Interagency Brucellosis Council in the early 1990s to drive cooperation was effective but flawed by bickering among those involved. The Department of the Interior (DOI) National Park Service (NPS); the USDA ARS, Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS), CSREES; state livestock and wildlife agencies; commercial groups; recreationalists; and Indian intertribal associations have widely opposed views, and there is no simple solution for the eradication of brucellosis. At the heart of the controversy is the lack of current research, which translates into lack of support for departments of wildlife and fisheries throughout the United States.

Educational Resources

Courses in the veterinary sciences in colleges of agriculture typically include one or two dedicated to agricultural undergraduate students and the remainder directed at graduate work in some phase of veterinary science. In most land-grant institutions, those educational resources and funding that supports them play little role in research.

Agricultural libraries, separate or as parts of major university libraries, provide major educational resources for research in veterinary science, particularly in production-animal medicine. Those facilities connect with AGRICOLA (Agriculture Online Access), a bibliographic database that contains veterinary medicine as a subject at http://stneasy.cas.org.

Financial Resources for Research

Funding for animal health research in colleges of agriculture comes from federal, state, and private sources. Much of the research in those facilities is under the sponsorship of agencies of the federal government. USDA’s CSREES has provided major funding to colleges of agriculture for research, graduate education, and infrastructure construction and maintenance. Funding has been through competitive and noncompetitive funding mechanisms that include Hatch funds (formula funds), the competitive grants of the National Research Initiative (NRI), Small Business Innovation Research grants, Biotechnology Risk Assessment grants (BRAGs), Animal Health Funds (1433), special grants program, and various programs targeted to help disadvantaged universities to develop and support agricultural research.

Although ARS is USDA’s in-house research agency, it has provided sparse research funds for production-animal research to universities and other institutions through specific cooperative agreements. ARS has the mission to develop and transfer solutions to agricultural problems of high national priority and provide information access and dissemination to ensure high-quality, safe food and other agricultural products. When outside expertise is needed to meet its mandated mission, ARS provides financial assistance to collaborative partners. Other sources of competitive and noncompetitive federal research funding to colleges of agriculture have included NIH, DOD, National Science Foundation (NSF), the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), DOI, the Department of Homeland Security, and the Department of Energy.

Since the middle 1950s, there has been a consistent increase in private support from industry and commodity groups for research in colleges of agriculture: “Between 1960 and 1992, private spending for food and agricultural research tripled” (USDA, 1999). By 1991, USDA expenditures for research and development (R&D) were less than 2% of all federal R&D spending ($1.2 of $61.3 billion), and about 4% of federal support for research in universities and college, was for agriculture ($408 million of $10 billion) (USDA, 1999).

The National Association of State Universities and Land-Grant Colleges (NASULGC) functions under the Board on Agriculture Assembly. This group does not fund or track research but supports colleges of agriculture in the funding process in Congress; for example, NASULGC supports the current presidential budget proposal to increase NRI grants by $120 million.

In the post-World War II period, federal funding for research was massively increased in the United States but less in USDA than in NIH, NSF, and other

federally supported research institutions. Much of the private support has been driven by commercial development of biotechnology, improved government-to-private technology transfer and establishment of intellectual property rights, and a closer association between research and economic development and marketing.

COLLEGES OF MEDICINE AND OTHER MEDICAL RESEARCH INSTITUTIONS

A portion of research in veterinary science occurs in schools and colleges of medicine and other medical research institutions, but it is essentially impossible to quantify. Some of the research takes place in departments of comparative medicine. The AVMA Membership Directory and Resource Manual (2004b) listed seven units in medical schools under the title “Departments of Comparative Medicine,” but some units have other names, such as “Section” and “Division.” Although the NIH National Center for Research Resources (NCRR) of NIH is listed in the AVMA Membership Directory Resource Manual, the Department of Comparative Medicine at Johns Hopkins University is not, nor is a unit of comparative medicine at the University of California, San Diego. A recent National Research Council, study National Needs and Priorities for Veterinarians in Biomedical Research (NRC 2004a), listed 27 (of a total of 38) clinical residency programs in laboratory animal medicine not associated with CVMs, giving some idea of the scope of research in veterinary science in medical schools and medical research institutions. The seven Regional primate research centers discussed later, all associated with colleges of medicine, also are sites of important research in veterinary science. There are a number of other medically oriented research institutions and centers throughout the country, including NIH, where research in veterinary science also takes place. Substantial advances in such subjects as animal genomics and infectious diseases occur in such research venues, but quantifying the resources available for such research is impossible (Sutter and Ostrander, 2004; Troyer et al., 2004).

The need for veterinarians in biomedical research was examined in the Research Council report National Needs and Priorities for Veterinarians in Biomedical Research (NRC, 2004a). The author committee studied national needs in comparative medicine, and its report included an analysis of the training opportunities in comparative medicine in schools and colleges of medicine. The committee’s major findings included the following:

-

“From 1995 through 2002, the number of NIH-funded competitive grants utilizing animals increased by 31.7%. There were approximately 1,300 more competitive grants utilizing animals in 2002 than in 1995.”

-

“Currently there are an estimated 1,608 research institutions in the US that are USDA-registered and/or hold NIH assurances indicating those institutions utilize animals in research programs.”

-

“The number of active laboratory animal medicine residency programs was the same in 1995 as it was in 2002. Of the 32 currently active programs, 9 of these programs did not have anyone complete a residency from 1996 to 2002.” This finding seems to be supported by a recent survey (2004) conducted by AAVMC. Seven departments of comparative medicine that are members of AAVMC were asked about the enrollment of graduate students. Two replied; one of the two reported that three students were seeking PhD degrees, and the other reported no graduate students.

Those and the data from NIH recorded elsewhere in this chapter are all the data the committee could locate regarding research in veterinary science conducted in medical schools and colleges and medical research institutions.

WILDLIFE AND AQUATIC HEALTH INSTITUTIONS

Research programs to solve wildlife and aquatic health, food safety, and well-being issues were created from pre-existing established programs focusing on conservation, and management of wildlife and more recently on improving production and quality in freshwater and salt-water farming operations of fish and other aquatic species. (See Appendix I for list of organizations in which major resources are directed to wildlife and aquatic health, food safety, and well-being.) Today, the ecological, societal, and financial importance of wildlife and aquaculture are enormous; but despite the importance and size of these sectors, neither has comprehensive centralized professional or government oversight or coordination of research priorities, funding, or sharing of information.

The research programs in wildlife and aquatic health, food safety, and well-being developed independently of the historical established research entities—that is outside the existing federal land-grant university and federal grants programs. That has not deterred individual scientists or groups of scientists or conservation and ecological organizations from developing successful and productive core programs of research at various universities and government and private institutions, which have emphasized and solved many wildlife and aquatic health, food safety, and well-being issues. In free-living wildlife, health research has focused largely on a few high-profile diseases. Those research programs tend to have narrow scope and short duration (AAWV, 2004). Seldom have big-picture efforts—such as comprehensive land-use planning for improving wildlife, livestock, and human health; ecosystem-level approaches; or even sustained efforts at managing very damaging diseases—been initiated or maintained for sufficient periods to make a difference (AAWV, 2004). Zoonotic issues at wildlife and domestic animal-human interface are emphasized in wildlife health research.

Infrastructure

Infrastructure, human resources, and physical resources are fragmented as small pieces scattered among multiple institutions. Institutions that have contributed to such research have included colleges and universities, state and federal government institutions, zoos and wildlife parks and aquariums, and private-foundation or corporate research institutions. The precise numbers of scientists and staff and square footage of research space are unknown, but the general impression from individual interviews is that resources dedicated to wildlife and aquatic health research are meager and much smaller than those dedicated to public health and to domestic livestock and poultry health and protection.

Some colleges of agriculture and CVMs have one to three faculty members studying wildlife and aquatic health. In a few institutions, there is a critical core of five to ten faculty members, and a formal program is established to focus on wildlife and aquatic health in an individual state or region. For example, the Southeast Cooperative Wildlife Disease Study in the University of Georgia CVM provides regional research and diagnostic services in wildlife health to southern states through five faculty and 24 other staff. In general, such larger formal programs are in states where wildlife, forestry, or aquaculture is financially important to the state or regional economy. The emphasis is on resource contribution by state governments through universities or game and fish departments. Examples are the Sybille Wildlife Research Facility at the University of Wyoming, Laramie, and the Center for Bison and Wildlife Health at Montana State University, Bozeman. In addition, research has been conducted through both inhouse and extramural programs of USDA’s ARS and APHIS and DOI’s NPS and US Geological Survey (USGS) in their core missions. Large federal programs in wildlife and aquatic health include

-

ARS: Aquatic Animal Health Research Unit Auburn, AL; and National Animal Disease Center, Ames, IA.

-

USGS: National Wildlife Health Center, Biological Research Division, Madison, WI.

-

APHIS: National Wildlife Research Center, Fort Collins, CO.

-

DOI’s US Fish and Wildlife Service: Fish and Wildlife Forensics Laboratory, Ashland, OR.

In wildlife health, the major dedicated wildlife research facilities are in Madison, WI; Ft. Collins, CO; Laramie, WY; and Athens, GA. Livestock facilities of ARS in Ames, IA, and Pullman, WA, are used for specific wildlife health research on infectious agents that cross between wildlife and domestic livestock (AAWV, 2004). Additional laboratory facilities and animal housing are available at various universities with general laboratory animal facilities, but they often are not constructed or staffed for wildlife care, and costs may be prohibitive or specific budgets to support wildlife research lacking (AAWV, 2004).

Expertise and Human Resources

Some 125-150 full-time veterinarians have clinical service, research, or teaching commitments in wildlife health in the United States, but their major commitment is to clinical service and not research (AAWV, 2004). The American Association of Wildlife Veterinarians estimated the distribution of veterinarians in different sections to be about 30-35 in federal government employment; 30-35 in state government employment; 25-30 employed by universities, institutions or cooperatives; 20-25 employed for tribes, under contract, or self-employed; and 20-25 employed by zoological societies, nongovernment organizations, or companies. The number of nonveterinarians in wildlife health research and the number of veterinarians and nonveterinarians in aquatic health are unknown.

Education

Educational opportunities for veterinarians and nonveterinarians in wildlife and aquatic health vary with job requirements and individuals needs. Experiential learning through on-the-job training has been the major method for developing expertise in clinical field research. Limited financial and formal training resources have been available through CVM’s and colleges of agriculture for training in wildlife and aquatic health. Some student training opportunities and externships are provided in zoological medicine, clinical care, and wildlife rehabilitation, but few externships or training programs are available that provide substantial experience in free-ranging wildlife. There are only two residency opportunities for wildlife veterinarians in the United States: one every third year at North Carolina and one focused on clinical care at the Wildlife Center of Virginia. Graduate studies (MS and PhD) in wildlife and aquatic health focusing on training and careers in research are available at institutions that have focused programs in wildlife and aquatic health, but funding and physical resources are scarce. Postdoctoral opportunities to work on wildlife are competitive and not abundant. Although classroom space can generally be found to support wildlife veterinary teaching needs, more-specialized facilities for wildlife veterinary and health research are almost nonexistent (AAWV, 2004).

ZOOLOGICAL INSTITUTIONS

The mission of most zoos is to conserve wildlife and to promote wildlife habitat conservation by increasing public understanding of their importance and their interdependence with humans. Few zoos can afford to support laboratory-based research programs in veterinary science (AZA Animal Health Committee, 2004). Therefore, only a few large zoos include research in their mission statements—for example, the National Zoological Park (NZP), the Saint Louis Zoo, and the San Diego Zoo. This section discusses the infrastructure and resources of

a few selected zoos that have substantial research activities. (The selection of zoos was based on the availability of information on their Web sites.) However, we note that such zoos are the exception, and that most zoos have only minor research capacities. Research programs at most zoos are designed to address specific problems in their collections (AAZV, 2004).

Organizational Structure

The scope and size of research programs vary from zoo to zoo. The Saint Louis Zoo’s research program focuses on reproduction, including behavior, physiology, endocrinology, and gamete biology. Its research unit is organized into three divisions—the Contraception Center, the Endocrinology Laboratory, and the Pathology Laboratory. The San Diego Zoo’s research is carried out at the Conservation and Research for Endangered Species Center (CRES). The center’s research focuses on applied conservation behavioral biology, ecology and evolution, endocrinology, genetics, giant panda conservation, pathology, and reproductive physiology. Research at NZP spans many disciplines, including reproductive biology, veterinary medicine, behavior, ecology, population biology, nutrition, migratory birds, and biodiversity monitoring.

Infrastructure

One of the largest research facilities associated with the zoo is the Conservation Research Center of the NZP. The center is a 3,200-acre facility in Front Royal, VA. The facility includes a geographic information systems laboratory, endocrine and gamete laboratories, a veterinary clinic, a radio tracking laboratory, 14 field stations, biodiversity monitoring plots, a conference center, dormitories, and education offices. Research is also carried out in the zoo in Washington, DC, where there are state-of-the-art nutrition laboratories, genetics laboratories, a reproductive-sciences facility, and a genome resource bank. Veterinary researchers have access to about 7,700 ft2 of laboratory space and share access to hospital, surgical, necropsy, and clinical laboratory space.

The San Diego Zoo completed the Arnold and Mabel Beckman Center for Conservation in 2004. The center is a two-story, 50,000-ft2 facility that includes 20,000 ft2 of laboratory space (with an additional 6,000 ft2 for future renovations) and 24,000 ft2 for offices, a library, a conference room, and a cryopreservation repository of biomaterials for endangered species. The center houses all divisions of the CRES except the giant panda conservation division.

Financial Resources

To the committee’s knowledge, there are no federal, state, or local government agencies whose mission is focused on veterinary research in zoos and

aquariums; considerable support for research relevant to zoos and wildlife comes from small foundations (Zoological Society of San Diego, 2004; AZA Animal Health Committee, 2004; NZP, 2004). However, research programs at zoos receive some support from federal agencies, such as NSF and NIH, provided that the projects are consistent with their missions. In 2004, NZP received about $1.1 million for research in veterinary science. Funds were obtained from competitive peer-review grant programs (for example that of NIH), endowments, foundations, corporate donors, and private donations.

Human Resources

In October 2004, the NZP reported that it had 23 full-time staff and 5 unfilled positions that are involved in veterinary science. Among the staff, 5 hold a DVM, 11 hold a PhD, and 8 hold both (NZP, 2004).

Educational Resources

NZP, the Saint Louis Zoo, and the San Diego Zoo all offer internships for college students and recent graduates. The San Diego Zoo offers veterinary internships exclusively to the University of California, Davis and Mesa College.

Graduate students and postdoctoral researchers could apply to study at NZP through the Smithsonian Fellowship Program. NZP also offers a veterinary student preceptorship that is targeted to students with a serious interest in veterinary medicine. It also leads one of the 14 residency training programs accredited by the American College of Zoological Medicine. The other zoos with such training programs include the Bronx Zoo, the Lincoln Park Zoo, and the Saint Louis Zoo.

Distribution of Resources and Disciplines

The ability of zoos to conduct research in animal health and veterinary science depends heavily on veterinary staffing levels because most staff can participate in research only on a part-time basis (AAZV, 2004). For example, the research capacity at the NZP’s Department of Animal Health was limited by a shortage of staff. Veterinarians have to meet the clinical needs of the zoo’s animal collection before they can participate in and contribute to veterinary research. Similarly, NZP’s Department of Conservation Biology has reduced research capacity because of delays in filling the vacant position for a PhD-level clinical nutritionist (NZP, 2004).

NATIONAL INSTITUTES OF HEALTH

NIH is the leading federal agency for health research in the United States and one of the world’s foremost medical research centers. “NIH provides leadership

and direction to programs designed to improve the health of the Nation by conducting and supporting research: in the causes, diagnosis, prevention, and cure of human diseases; in the processes of human growth and development; in the biological effects of environmental contaminants; in the understanding of mental, addictive and physical disorders; in directing programs for the collection, dissemination, and exchange of information in medicine and health, including the development and support of medical libraries and the training of medical librarians and other health information specialists” (http://www.nih.gov/about/almanac/index.html).

Organizational Structure

NIH is organized into 27 institutes and centers that are managed under the Office of Director. Veterinarians and veterinary scientists are involved in research, program direction, and management in several institutes and centers, including the National Cancer Institute (NCI), the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI), the National Institute on Aging, the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, and especially the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, and NCRR.

Expertise and Human Resources

NIH employs veterinarians in various roles, such as staff scientist, veterinary medical officer, supervisor of veterinary medicine, research fellow, senior investigator, senior scientist, staff veterinarian, and research veterinary officer. The number of veterinarians employed at NIH has been difficult to determine but most likely is at least 65. It is unclear how many DVMs are involved directly in research as opposed to the support of the overall mission of NIH.

Financial Resources

The extramural programs of most centers and institutes do not provide direct support for research in veterinary science, because NIH’s primary mission is to improve human health. Nevertheless, most centers and institutes provide extramural funds for animal research that contributes to the enhancement of human health and welfare. For example, from 1990 to 2002, research based on the use of live vertebrate animals accounted for about 43% of competitively funded NIH grants (NRC, 2004a). During the period 1995-2002, the total number of research grants increased, which resulted in a 31.7% increase in the number of competitive grants involving animals; this translates into funding for about 1,300 more grants using animals in 2002 than in 1995 (NRC, 2004a).

Another example of success in funding veterinary medical initiatives came through NHLBI. In the early 1980s, the institute initiated the Transfusion Medi-

cine Academic Award (TMAA) program, intended to provide more academic and postdoctoral training in the growing field of transfusion medicine. That was in response to the discovery of AIDS and an increasing concern about transfusion-transmitted diseases and blood safety in human medicine. As with any federally funded program, physicians and members of allied health professions are eligible to apply. The deans of CVMs were contacted and alerted to the availability of funds, which would be provided to a successful faculty applicant for 5 years to develop a program in the basic and clinical aspects of transfusion medicine for students and residents and for continuing education. After the award period, the recipient institutions were expected to continue the program on their own. In 1985, the first veterinary schools applied for the TMAA; there were 16 applications—12 from CoMs and four from CVMs. Four applications were funded, and CVMs received two of them. Since the program’s inception in 1983, 40 TMAAs have gone to 35 CoMs and five to CVMs, and NHLBI has invested $1.5 million in transfusion medicine programs in CVMs.

In 1998, NCI announced an initiative titled “Mouse Models of Human Cancers Consortium”; it funded 19 groups of investigators at 30 institutions to develop models related to how human cancers develop, progress, and respond to therapy or preventive agents. NIAID has been the primary sponsor of programs in the use of animal models for the prevention and treatment of hepatitis B and C, nonhuman-primate heart and lung transplantation tolerance, research in biodefense and emerging infectious diseases, and construction of regional biocontainment laboratories.

NCRR is most closely tied to research in veterinary science and provides substantial funding. It supports animal research that contributes to biomedical sciences but is not in the categorical interest of a single NIH institute or center. It also supports projects that address such direct animal needs as the welfare of laboratory animals, and animal pain perception. The mission of NCRR is to support “primary research to create and develop critical resources, models, and technologies. NCRR funding also provides biomedical researchers with access to diverse instrumentation, technologies, basic and clinical research facilities, animal models, genetic stocks, biomaterials, and more. These resources enable scientific advances in biomedicine that lead to the development of lifesaving drugs, devices, and therapies” (http://www.ncrr.nih.gov). The number and types of research and training grants awarded to veterinary researchers by NCRR were discussed in another National Research Council report (NRC 2004a).

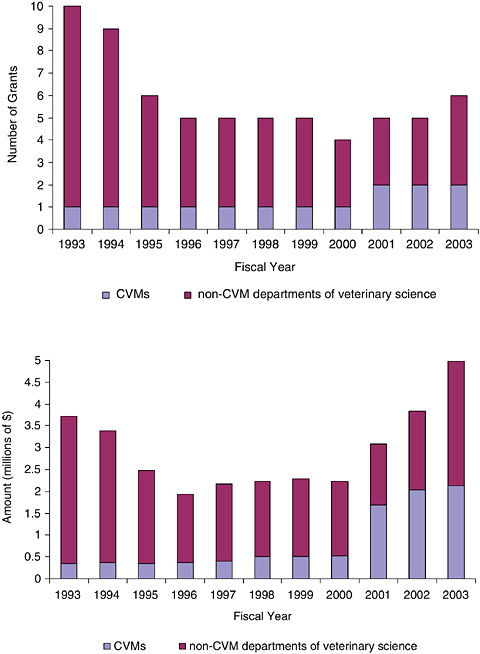

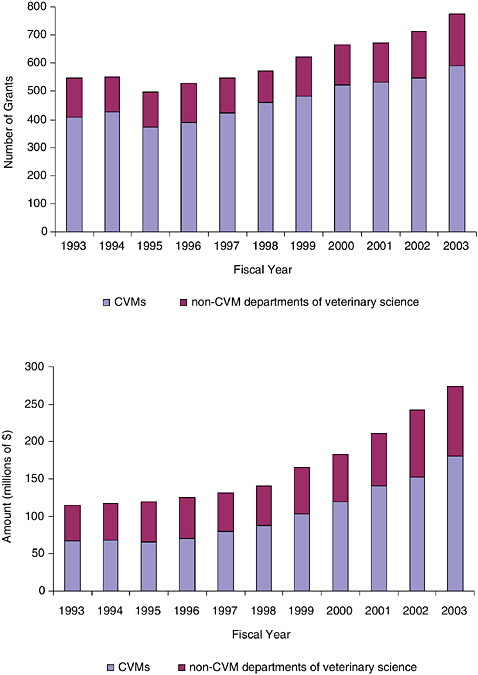

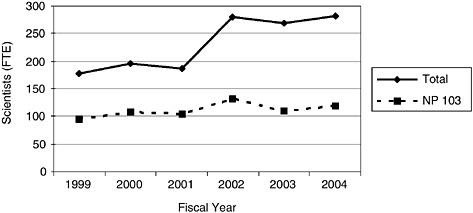

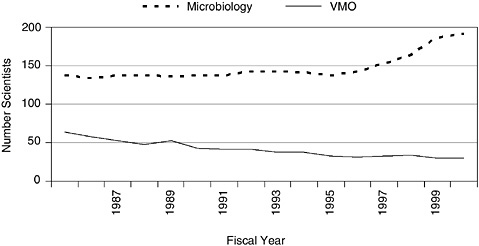

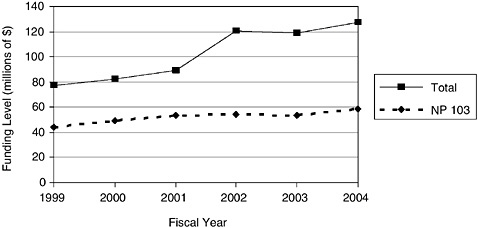

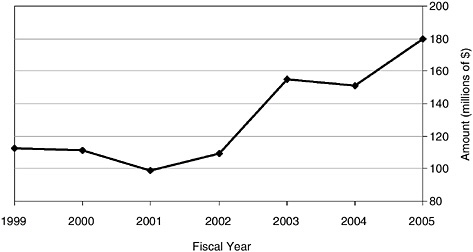

CVMs and departments of veterinary science and comparative medicine (DVS/CMs) have received various NIH awards (Figure 4-3), including R01 (research project; Figure 4-4), P01 (research program projects; Figure 4-5), and P40 (animal model & animal and biological material resource grants; Figure 4-6). (See Appendix J for 10-year funding trend of other NIH awards to CVMs).

The total number of NIH grants—including all C, D, F, G, K, S, P, R, T, and U grants—awarded to CVMs increased 45% (from 407 to 590) and award dollars

FIGURE 4-3 Total number and value of NIH grants. Number and total value of NIH grants (including all C, D, F, G, K, S, P, R, T, and awards) awarded to colleges of veterinary medicine and departments of veterinary science that are not affiliated with Colleges of Veterinary Medicine. SOURCE: NIH Office of Director.