2

The Innovation Process

Understanding the innovation process is essential to establishing strategies for technology transfer. This chapter begins by briefly describing the innovation process in the highway industry on the basis of a traditional linear model. This model is then revised to illustrate the dynamic nature of the process by including several communication and other linkages involving individuals, groups, and organizations. Finally, the discussion focuses on technology transfer and the adoption of innovations, the relationship between the two, and their role in the innovation process.

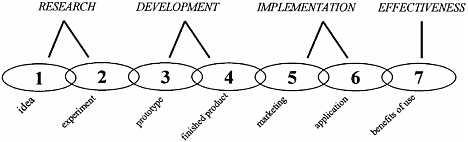

The development of models based on stages or activities of a process is a familiar mechanism for bringing order to and better understanding the process. Traditionally, linear models have been used to model innovation (Kline and Rosenburg 1986). Figure 2-1 presents such a model, used to describe the sequence of events from research idea to implementation of the research product in the highway industry (Kulash 1997). This model, representing the point of view of the source or production of technology, comprises seven stages. Research and develop-

ment (R&D) usually ends within Stage 4; technology transfer typically focuses on the activities within Stages 5 through 7.1

While the traditional linear model is a helpful beginning and highlights some of the major steps involved, it misrepresents the innovation process by depicting it as smooth and well behaved (Kline and Rosenburg 1986). A linear model of innovation is inherently limited because the process is not quite so simple. A linear model cannot describe the differences, relationships, and interdependencies among stages; the large number of participants involved; or the full array of activities required to achieve implementation. Consequently, such a model is inadequate for establishing strategies and providing guidance for the management of a technology transfer program.

Figure 2-2 presents a revised model of the innovation process that incorporates additional details reflecting characteristics of the highway industry. For example, once an idea has evolved into a research product, the product is available for use by state and local highway agencies. The revised model includes stages associated with specification and procurement obstacles, the contractors (and others) who will be asked to adopt and adapt to the innovation, and the specific project applications that will yield the benefits of use of the product. The model portrays these stages in both the vertical and horizontal dimensions to represent an innovation process that moves forward (horizontally) in time, as well as upward (vertically) to overcome resistance or barriers. Included in Figure 2-2 are some of the feedback loops and input channels that

Figure 2-1 Linear model of highway industry innovation (Kulash 1997).

Figure 2-2 Revised linear model illustrating inputs and feedback by specific participants.

can affect highway industry innovation; others might be included, depending upon the particular technology involved.

No single model can adequately represent all the variations in stages, timing, participants, input channels, and feedback loops. Kline and Rosenburg (1986) propose a chain-linked model for innovation, showing flow paths of information and cooperation between and among

stages. Tornatzky et al. (1990) suggest that the stages of innovation should be defined not as steps on a stairway, but as rooms connected by a large number of doors.

Participants in the innovation process often provide new technologies, important feedback on implementation experience, new ideas for additional research, and assistance in fostering more widespread application. Some play multiple roles in research and implementation. Among the many highway industry participants and their contributions to innovation are the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) and state highway agencies; committees and activities of the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO) aimed at standards setting and identification of research needs; research programs of state highway agencies that generate research products and carry out field tests; university R&D programs; Transportation Research Board (TRB) technical committee activities; association activities; and courses of instruction provided by the National Highway Institute on implementing specific technologies.

Analyses of private-sector innovation focused on product commercialization emphasize the need for continuous feedback among corporate researchers, marketing divisions, and potential customers, reflecting the need for responsiveness to marketplace demands. The link from research to innovation “is not solely or even preponderantly at the beginning of typical innovations, but rather extends all through the process” (Kline and Rosenburg 1986, 289). Consequently, research questions can and do arise throughout the development process.

Market forces that create incentives for innovation in the private sector operate differently in the public sector. Many innovations developed and adopted by private contractors are aimed at gaining a competitive advantage over other contractors bidding on public-sector contracts, rather than achieving an improved final product. The stimulus for implementing new technology in the public sector comes from regulations, financial incentives, expansion or new construction, or equipment or material failures. It can also come from technology transfer and technical assistance programs. Technology transfer is an enabling mechanism that supports and, particularly in the public sector, encourages and promotes innovation. A number of characteristics of the public sector, and the highway industry in particular, act as barriers

to innovation, and these barriers must be specifically addressed as part of the technology transfer effort (see Chapter 3).

TECHNOLOGY TRANSFER

As noted previously, technology transfer has been defined as the movement of technological and technology-related organizational know-how among partners. Technology transfer activities are aimed at (1) identifying innovative technologies available for use in the highway industry immediately or after some adaptation; (2) selecting and prioritizing technologies to be promoted to the highway industry; (3) determining, developing, and applying effective technology transfer methods to promote the technologies; and (4) continually modifying the technology transfer process in accordance with feedback on which technologies and which methods of technology transfer have been successful. Although the purpose of technology transfer in the private sector is to “enhance at least one partner’s knowledge and expertise and strengthen each partner’s competitive position” (NAE 1997, 2), public-sector technology transfer focuses on getting technology known and implemented. Howitt and Kobayashi (1986) suggest that technology transfer consists of complex relationships among organizations, with participants having significant interests at stake and perceiving varying incentives for becoming involved in technology transfer and implementation activities. Like the innovation process, technology transfer is usually iterative, involving many individual steps.

Technology transfer can begin when users describe specific needs to researchers or developers of technology. The process includes all the activities of the researchers, technology users, and technology transfer staff that lead to the adoption of new or different products or procedures (TRB 1998). Technology transfer can occur through informal interactions between individuals; formal consulting agreements; publications; workshops, personnel exchanges, and joint projects involving groups of experts from different organizations; and more readily measured activities such as patenting, copyright licensing, and contract research (NAE 1997).

The above definition of technology transfer encompasses both direct and indirect forms. Direct or active technology transfer is linked to

specific technologies or ideas and to more visible channels, such as cooperative research projects or partnering agreements. Indirect or passive technology transfer involves the exchange of knowledge through such activities as informal meetings, publications, workshops, and conferences. In the early stages of the technology life cycle, indirect technology transfer predominates, so it is often difficult to trace the origins of specific technologies or ideas. Nevertheless, a robust innovation process benefits from inputs and feedback from many sources.

Public agencies are particularly reliant on technology transfer programs for several reasons. The large volume of R&D under way and the dispersion of R&D agencies serve as deterrents to anyone seeking useful technical information, especially public agencies with limited financial resources and personnel. Few research products are self-executing, so users must rely on outside experts to understand how to adopt the new products effectively. Potential users need information on the limitations and capabilities of research products to avoid wasting time and resources in attempting to fit a technology to an incompatible use. Technologies that are particularly sophisticated, different from those currently used, or costly to adopt may require adaptation before being employed in specific applications or may necessitate considerable accommodation by the users (Lemer and Tornatzky 1991).

Without technology transfer programs, local public agencies would find it difficult to make decisions about new technologies (Bikson et al. 1996). Local agencies are often hindered by limited knowledge of innovative new technologies, a lack of funds for initiating programs involving such technologies, and limited technical expertise to assist in implementation ( Jacobs and Weimer 1986). Professional and trade journals provide information, but technical details are often lacking. Moreover, “unlike their private counterparts, public managers cannot look to the profitability of competitors as an indication of successful innovation, and they are not punished in the marketplace for failing to adopt the most efficient technologies” ( Jacobs and Weimer 1986, 139). As a consequence, technologies can be available for many years and widely adopted while they continue to be implemented for the first time by some local agencies. (See also Chapter 3.) Any improvement over existing technologies or processes, not necessarily a chronologically recent innovation, is new to the implementing agency (Schmitt et al. 1985).

INNOVATION ADOPTION

Studies of innovation adoption indicate that it involves several phases for both individuals and agencies (Rogers 1962) (see Table 2-1). Each of these phases benefits from technology transfer activity. During the initial awareness phase, potential users observe an innovation or new technology and decide whether to seek more information about it. In the next phase, attitude formation and persuasion, the potential user actively seeks more information and forms some initial impressions. The appropriateness of the innovation for the user’s situation is then assessed, and an adoption decision is made. In the final phase, the user continues to seek information to confirm acceptance or rejection of the innovation. Figure 2-3 illustrates these phases relative to time and user involvement.

Another aspect of innovation adoption is important to technology transfer. Adoption of new technologies by implementing agencies varies over time. Some technologies are adopted quickly, while others never exhibit more than a slow rate of adoption. Although the concept of

Table 2-1 Phases in the Innovation Adoption Process

|

Phase |

Description of User Involvement Phases |

|

Awareness |

A potential user first observes an innovation or new technology and gains some understanding of how it functions. Such awareness may be entirely passive; lacking complete information, the potential user may not yet be motivated to seek further information. |

|

Attitude Formation and Persuasion |

The potential user becomes interested in the innovation and actively seeks additional information in order to form some attitude toward it. |

|

Trial and Decision |

The innovation is assessed, and an adoption decision made. A trial period may ensue. Performance is one of the decision factors. |

|

Confirmation |

The potential user continues to seek information to confirm the adoption decision made. A decision can be reversed if there is conflicting information. |

Figure 2-3 S-curve illustrating involvement of individuals at different stages of the innovation adoption process (Rogers 1962).

adoption rates is widely accepted, data are scarce for comparison purposes, especially for public-sector technologies. Moreover, at some point, demand for specific technologies tapers off; sometimes a new technology is overtaken by a more recent innovation (Feller 1981). As a result, there is a point at which technology transfer activity can be scaled back or dropped because further activity would be unproductive.

In most cases, moving technology from the research environment to an operating environment involves considerable technology transfer effort and resources. The effort goes beyond information dissemination and exchange to encompass technical assistance and user training (EPA 1991). Successful technology transfer programs depend on effectively segmenting user audiences, and tailoring strategies to those audiences and to different stages of the technology development

process. Successful programs also involve obtaining feedback from technology transfer clients to assess whether the technology exchange has been successful.

NOTES

|

|

1. Boundaries between the stages of innovation are not always well defined; there is considerable overlap of activity between all stages. |

REFERENCES

ABBREVIATIONS

EPA Environmental Protection Agency

NAE National Academy of Engineering

TRB Transportation Research Board

Bikson, T. K., S. A. Law, M. Markovich, and B. T. Harder. 1996. Facilitating the Implementation of Research Findings: A Summary Report. NCHRP Report 382, National Research Council, Washington, D.C., 24 pp.

EPA. 1991. Innovative Technology Transfer Workbook: Planning, Process, Practice; Draft Version 1. Prepared by Technical Resources, Inc., Washington, D.C., Aug.

Feller, I. 1981. The Diffusion and Utilization of Scientific and Technological Knowledge in State and Local Governments. Pp. 131–150 in Technology Transfer by State and Local Governments (S. Doctor, ed.). Cambridge, Mass., Oelgeschlager, Gunn and Hain.

Howitt, A., and R. M. Kobayashi. 1986. Organizational Incentives in Technical Assistance Relationships. Pp. 119–136 in Perspectives on Management Capacity Building (B. W. Honadle and A. M. Howitt, eds.). State University of New York Press.

Jacobs, B., and D. L. Weimer. 1986. Inducing Capacity Building: The Role of the External Change Agent. Pp. 139–162 in Perspectives on Management Capacity Building (B. W. Honadle and A. M. Howitt, eds.). State University of New York Press.

Kline, S. J., and N. Rosenburg. 1986. An Overview of Innovation. Pp. 275–305 in The Positive Sum Strategy (R. Landau and N. Rosenburg, eds.). NAE, National Research Council, Washington, D.C.

Kulash, D. 1997. Improving the Effectiveness of Highway Research: Reflections from the SHRP Experience. TR News, No. 188, Jan.–Feb., pp. 4–9.

Lemer, A., and L. G. Tornatzky. 1991. Processes of Technological Innovation. Appendix B in The Role of Public Agencies in Fostering New Technology and Innovation in Building. Committee on New Technology and Innovation in Building. Building Research Board, National Research Council, Washing-ton, D.C.

NAE. 1997. Technology Transfer Systems in the United States and Germany. National Academy Press, Washington, D.C.

Rogers, E. M. 1962. Diffusion of Innovations. The Free Press of Glencoe, New York.

Schmitt, R. P., E. A. Beimborn, and M. J. Mulroy. 1985. Technology Transfer Primer. FHWA-TS-84-226, University of Wisconsin, July.

Tornatzky, L. G., J. D. Eveland, and M. Fleischer. 1990. Technological Innovation: Definitions and Perspectives. Pp. 9–26 in The Processes of Technological Innovation (L. G. Tornatzky and M. Fleischer, eds.). Lexington Books, Boston, Mass.

TRB. 1998. Transportation Research Circular 488: Transportation Technology Transfer—A Primer on the State of the Practice. National Research Council, Washington, D.C., May.