7

Implementation Strategy

7.1 IMPLEMENTATION STRATEGY OBJECTIVES

The effective and efficient realization of FORCEnet capabilities requires an implementation strategy on the part of the Navy and the Marine Corps. “Implementation” is taken here in the broad sense of ranging from initial conceptual thinking through the establishment of capability in fielded forces. The previous chapters of this report deal with the various aspects of FORCEnet implementation strategy. From that work, the following set of objectives for the strategy can be abstracted:

-

Provide clarity of purpose. The implementation strategy should make clear the nature of the capabilities to be developed under the FORCEnet initiative. In particular, important points of scope need to be made clear in order to guide implementation properly.

-

Establish an environment and process for the continuous capability evolution and innovation. As new technical capabilities are explored, new concepts for their application will be discovered and requirements for additional capabilities will be generated. Furthermore, the security environment in which the naval forces operate will continue to change, necessitating new capabilities on the part of the force. Thus, a “closed-form solution” for the development of FORCEnet capabilities cannot be specified in advance—rather, an evolutionary approach is necessary.

-

Apply a forcewide perspective to materiel development. The nature of network-centric operation is that all components of the force (weapons, sensors, C2 systems, communications, and so on) will relate to and draw upon one an-

-

other. Thus, these components cannot be designed alone, but only in relation to the other components.

-

Integrate with joint developments. All recent combat operations have been joint, and the extent of joint interaction in military operations is only likely to increase. Thus, FORCEnet operational and materiel capabilities must be developed in a joint context.

These objectives are closely related to one another. The environment and process referred to in the second objective enable the overall realization of FORCEnet capabilities. Addressing the need for a forcewide perspective in materiel development, the third objective bores more deeply into one aspect of the process that warrants particular elaboration, and the fourth objective, calling for the integration of FORCEnet capabilities with joint developments, recognizes that the whole process must couple into larger DOD-wide processes. All consideration of the implementation process must be preceded by a clear understanding of what is sought from the process, which is what the first objective, calling for clarity of purpose, requires.

Drawing on the findings and recommendations presented in previous chapters, the sections below elaborate on the objectives, assess how the Naval Services are doing in realizing them, and indicate what more could be done to achieve them.

7.2 CLARITY OF PURPOSE

The definition of FORCEnet is as follows:

[FORCEnet is] the operational construct and architectural framework for naval warfare in the information age that integrates warriors, sensors, networks, command and control, platforms, and weapons into a networked, distributed, combat force that is scalable across all levels of conflict from seabed to space and sea to land.1

This definition is adequate as a point of departure for the implementation of FORCEnet capabilities, but further elaboration is necessary in order to provide clarity of purpose to all those involved in the implementation. While the definition is quoted quite widely in the Navy and Marine Corps, the committee found little elaboration on two key phrases in it—“operational construct” and “architectural framework.” Put simply, the committee took the operational construct to be

the set of concepts of employment for the naval force, and the architectural framework to be the set of architectures describing the structure and relationship of the components of the force. Nevertheless, further elaboration is required to define what constitutes a satisfactory operational construct and architectural framework.

An additional point requiring elaboration relates to the scope of the definition of FORCEnet. In particular, the definition implies that FORCEnet applies to the entire force, not just to the network or information infrastructure as is sometimes implied in writings on FORCEnet. This fact has significant implications for the necessary scope of the concepts of employment and architectures, as is discussed in the sections below. To be clear on this important point: in this report, FnII refers specifically to that infrastructure component of the force, and the word “FORCEnet” alone refers more generally to the force.

As one final point, the discussion here indicates that FORCEnet—as concepts of employment and architectures—is composed of those processes and descriptive items that guide the implementation and realization of network-centric capabilities in the force rather than being the implemented components themselves. The implemented components are referred to using “FORCEnet” as a modifying term—for example, “the FORCEnet Information Infrastructure.”

To provide better clarity of purpose, the committee recommends the following:

-

Recommendation for OPNAV, NETWARCOM, and MCCDC: Articulate better the meaning of the terms “operational construct” and “architectural framework” in the description of FORCEnet and indicate how FORCEnet implementation measures relate to each of these concepts. (Recommendation 1)

-

Recommendation for OPNAV, NETWARCOM, and MCCDC: Make clear that FORCEnet applies to the entire naval force and not just to its information infrastructure component. In so doing, the organizations should specifically indicate that the concepts of employment and the architectures developed must apply to the operation of the whole force and not just to its information infrastructure component. (Recommendation 2)

The action parties in Recommendations 1 and 2 are so chosen because they are the primary organizations describing the nature of the FORCEnet initiative.

7.3 CONTINUOUS CAPABILITY EVOLUTION AND INNOVATION

7.3.1 Functional Areas for FORCEnet Capabilities Implementation

Broadly speaking, the overall process for implementing FORCEnet capabilities centers on five functional areas pertaining to (1) operational concepts, (2) re-

quirements, (3) programs and resources, (4) acquisition, and (5) engineering.2 The responsibilities in these areas, and the Navy offices assigned these responsibilities, are shown in Table 4.1 in Chapter 4.3

The process flow through the functional areas could simply be viewed as a linear sequence, from the development of operational concepts through engineering execution. In fact, the situation is highly iterative owing to the coevolution of operational concepts and technology development and the changing nature of the national security environment. This fact is so fundamental that the committee singles it out by recommending the following:

-

Recommendation for the CNO and the CMC: Promote as a guiding principle that the realization of FORCEnet capabilities will require a process of continuous evolution, involving the close coordination and coupling of the individual departmental functional processes—operational concept and requirements development, program formulation and resource allocation, and acquisition and engineering execution. (Recommendation 3)

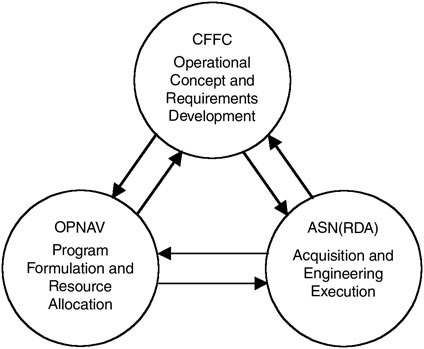

The coupling and iteration of individual departmental functional processes are suggested in Figure 7.1. Note from Table 4.1 that within the Navy, one major organization (and its subordinates) has responsibility for each of the “spheres” in the figure—the CFFC, OPNAV, and the ASN(RDA).

The objective of Recommendation 3 is to make the overall implementation process for FORCEnet capabilities as effective as possible. This means achieving maximum effectiveness for the interactions between the functional areas, as suggested by the arrows in the figure, as well as for the individual functional areas (represented within the spheres in Figure 7.1). The next two subsections examine the individual functional areas and the cross-functional interactions, respectively.

7.3.2 Assessment of Individual Functional Areas

7.3.2.1 Operational Concept and Requirements Development

The committee makes the following observations about the functional areas of operational concepts and requirements. These observations refer to the Sea

|

2 |

Training, an important additional functional area, is not considered here, since it is outside the scope of the study as specified in its terms of reference (see Appendix A). Clearly, significant attention needs to be paid to training for both the operational and the technical aspects of network-centric operations. |

|

3 |

The study also presents implementation responsibilities for the Marine Corps (Table 4.2), but the extent of the study’s examination did not allow it to develop an assessment of those responsibilities as it did for the Navy. |

FIGURE 7.1 Implementing FORCEnet.

Power 21 pillars—Sea Basing, Sea Strike, and Sea Shield—as well as to FORCEnet per se, since FORCEnet capabilities follow from the capabilities required for the pillars.

-

Very little detail has been developed for articulating new operational concepts—only limited descriptive material and certainly nothing with the sort of detail typically found in operational architectures.4 This lack is most likely a consequence of the very limited resources committed to this area. The Second and Third Fleets devote only a few people part time to concept development for the three Sea Power 21 pillars. NETWARCOM appears to have a larger, although still small, commitment of resources to FORCEnet concept development. Representatives of the said organizations, especially the Second and Third Fleets, indicated to the committee that these limited commitments were a consequence of the many demands (e.g., maintaining readiness) placed on these organizations.

-

The Second and Third Fleets and NETWARCOM indicated a serious commitment to experimentation, although generally one of modest scope. The Second Fleet is active in exploring the use of prototype equipment, the Third Fleet has a history of experimentation centered around the USS Coronado com-

-

mand ship, and NETWARCOM is conducting the Trident Warrior series of exercises. NETWARCOM’s experimentation thus focuses largely on the FnII.

-

CFFC has underscored the importance of experimentation by issuing a new experimentation instruction (CFFC Instruction 3900.1A for Sea Trial). Furthermore, it has reduced the number of the large fleet battle experiments to allow more of the smaller, limited objective experiments, which should promote greater exploration and innovation. The Sea Trial instruction promotes greater Navy-wide interaction, thereby potentially bringing more ideas and resources to experiments. At the same time, though, this instruction establishes greater centralized control in approving experiments, which might stifle the very innovation that experimentation seeks to promote.

-

NETWARCOM has an active program for FORCEnet requirements development, drawing widespread community participation though its OAG. The OAG does not use any formal analytical methods to relate the requirements to warfighting effectiveness, relying rather on the collective judgment of the group.

-

The Second and Third Fleets demonstrated only very limited requirements development for the three Sea Power 21 pillars. This limited work is most likely a consequence of limited resources, as described above for operational concepts development.

Based on the preceding observations, the committee recommends the following:

-

Recommendation for NETWARCOM, and the Second and Third Fleets especially: Devote significantly more resources to concept development. The criticality of concept development to the overall realization of FORCEnet capabilities certainly requires this increase. The committee also recommends that CFFC determine whether the increased resources would come by reassigning personnel already assigned to the organizations or by request to the CNO for additional personnel. (Recommendation 4)

-

Recommendation for the CNO: Assign the Pacific Fleet greater direct responsibility in Sea Power 21 concept development. This action would apply the sizable resources and operational experience of Pacific Fleet to help redress the current limitations in resources devoted to concept development. The action would also help strengthen the joint aspects of concept development through Pacific Fleet’s relation with PACOM. (Recommendation 5)

-

Recommendation for the CFFC: Ensure that NETWARCOM plays as broad a role in FORCEnet concept development and experimentation as possible—not just limited to the use of the FnII. This is consistent with NETWARCOM’s charter and reflects the fact that FORCEnet refers to forcewide capabilities. (Recommendation 6)

-

Recommendation for the CFFC: Ensure that the centralized management processes of the new Sea Trial instruction do not stifle innovation. Local initia-

-

tive is critical to innovation. The Sea Trial management mechanisms should concern themselves with setting broad guidelines and resource allocations within which individual elements in the Navy would be free to innovate. Every experiment, no matter how small, should not require approval by a centralized committee, as would appear to be the case with the new Sea Trial instruction. (Recommendation 7)

-

Recommendation for NETWARCOM: Develop analytical means for the determination and prioritization of requirements. This would allow requirements to be tied better to warfighting effectiveness and would thereby better support these requirements in the resource-allocation process. (Recommendation 8)

-

Recommendation for the Second and Third Fleets: Devote more resources to the development of requirements for the three Sea Power 21 pillars. Needed capabilities for the pillars must be adequately specified in order to determine the necessary FORCEnet capabilities. Means to obtain these resources would be addressed by reassigning personnel already assigned to the organizations or by request to the CNO for additional personnel. (Recommendation 9)

7.3.2.2 Program Formulation and Resource Allocation

The N6/N7 and N8 use four NCPs—Sea Strike, Sea Shield, Sea Basing, and FORCEnet—in their program formulation and resource-allocation process. Each of these NCPs is further divided into Mission Capability Packages. Those for the FORCEnet NCP are Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance; Common Operational and Tactical Pictures; and Networks. As discussed above (Section 7.2), FORCEnet comprises concepts of employment and architectures referring to the entire force, but in the NCP context, the Navy uses the term FORCEnet differently—basically as the FnII (interpreted to include some information-producing assets).

A major shortcoming of the current resource allocation process is thus that it is not configured to implement FORCEnet capabilities, interpreted in their full extent. At most, the process does single out the FnII for resourcing, but in a way that has it competing against the other NCPs, rather than recognizing that the FnII is an enabler of these NCPs.

The problem is further compounded by the limited modeling and simulation tools available to support resource priority decisions. Tools currently used by OPNAV require significant time to set up, thus limiting the number of scenarios that can be examined per budget cycle. In addition, the models and simulations used are of the traditional, attrition-based type, with only limited inclusion of the network and information dimensions of warfare—which are at the heart of FORCEnet capabilities.

Based on these observations, the committee recommends the following:

-

Recommendation for the N6/N7 and N8: Develop resource-allocation methods directed at realizing forcewide FORCEnet capabilities. Instead of basing

-

the methods on the current Naval Capability Packages, the Navy should instead use “packages” that inherently reflect network-centric operational concepts. FORCEnet Engagement Packs provide one such example. (Recommendation 10)

-

Recommendation for the N6/N7 and N8: Develop (or acquire) modeling and simulation tools that allow faster exploration of scenarios and better measurement of the effects and limitations of information availability and network connectivity in warfare. This will not be an easy task since such tools are in their infancy, but the Navy should be a proponent for the development of these tools. (Recommendation 11)

7.3.2.3 Acquisition and Engineering Execution

5All acquisition activity is under the authority of the ASN(RDA). In this capacity, the ASN(RDA) oversees the PEOs, program managers, systems commands, and ONR. In January 2004, the ASN(RDA) led the first meeting of the FORCEnet EXCOMM to address FORCEnet implementation issues. The subjects treated included establishing a FORCEnet implementation baseline and redirecting some current-year funds to support FORCEnet objectives. The decisions and actions of the EXCOMM represent a good start in addressing FORCEnet implementation issues, demonstrating a focus on the future, and communicating an urgency for FORCEnet implementation. The meeting, however, had only very limited attendance from the fleet commands; greater senior-level representation of the fleet command perspective would aid the deliberations at future meetings.

Two significant challenges face the acquisition community in implementing FORCEnet. The first is the need for flexible resource allocation. That is, FORCEnet pertains to the interaction and interoperation of systems across the fleet. Thus, the programs for these systems must be brought forward in as synchronized a manner as possible, which will require the reallocation of funds across programs as problems arise in the development of individual programs and as schedules are adjusted. The EXCOMM’s deliberations recognize this problem, but the Navy (as with all of the military Services) is restricted in this regard by the congressional limitations on the transfer of funds between programs.

The second challenge is the need for speed to capability, specifically relating to applying information technologies. That is, the rapid pace of technology change requires that operational users be provided capabilities quickly, before they become obsolete. Furthermore, the whole concept of spiral development implies that system solutions must be developed evolutionarily in concert with operator involvement, and not delivered after the completion of a long-term program without operator involvement. In general, the committee did not get a sense for

|

5 |

A significant activity of the engineering component is the development and use of architectures. That subject is treated in Section 7.4. |

the rapid development of capability in many of the briefings that it received. Often, no near-term capability delivery (e.g., within 1 year) could be identified. Speed to capability is a matter broader than just the acquisition community (e.g., requirements development is a factor), but greater attention to this matter within the acquisition community is necessary.

The preceding considerations lead the committee to recommend the following:

-

Recommendation for the ASN(RDA): Take action to include senior members of the fleet commands in the deliberations of the FORCEnet EXCOMM. Their perspective in general would be useful. In particular, the actions necessary to implement FORCEnet capabilities in a fixed-resource environment could impact near-term fleet readiness and should be accomplished in partnership with fleet representatives. (Recommendation 12)

-

Recommendation for the ASN(RDA): Explore methods for increasing flexibility in resource allocation. One approach for doing so is to aggregate program line items into larger line items, including the possibility of establishing a few major lines referring to FORCEnet capabilities (e.g., for implementation of the FnII or for the systems engineering required across the entire fleet). The Navy, in conjunction with the other military Services, could also consider approaching Congress to relax the limit on reallocating program funds. A strong argument for this authority could be made on the basis of the current need to field systems of systems, in contrast to the previous focus on individual systems. (Recommendation 13)

-

Recommendation for the ASN(RDA): Review Navy acquisition processes and practices and institute educational measures as necessary, to ensure that programs are providing as rapid a delivery of capability as possible. For example, financial practices could be reviewed to determine means for emphasizing rapid capability delivery while maintaining accountability, and execution instructions could be reviewed to ensure that there is adequate delegation of authority. (Recommendation 14)

7.3.3 Assessment of Cross-Functional Interactions

The implementation of FORCEnet capabilities requires an evolutionary approach. Whether one calls this coevolution or spiral development or some similar phrase, what is needed is an effective, highly iterative process coupling the three spheres of responsibility shown in Figure 7.1 above. Such a process requires effective interactions between the individual spheres and among all of them.

7.3.3.1 Discussion of the Interactions

The following describes needed interactions and assesses their realization in current Navy practice.

-

Operational concept and requirements development—program formulation and resource allocation. In this interaction, the requirements developed under the direction of the CFFC need to be reflected adequately in the program development and prioritization activities of the N6/N7. The FORCEnet requirements developed by NETWARCOM are addressed in the OPNAV programs, but OPNAV uses a priority ranking different from that submitted by NETWARCOM.

-

Program formulation and resource allocation—acquisition and engineering execution. The programs developed by OPNAV are provided to office of the ASN(RDA) for execution, given budget approval. Beyond that, however, tight interaction between the two organizations is necessary in order to resolve frequent issues of functional allocation and resource adjustments that will arise in program execution, given that FORCEnet relates to the whole fleet. That is, these issues should not be resolved by the acquisition parties alone; they also require the participation of those who developed the rationale and priorities for the programs. Mechanisms to provide this tight coupling between OPNAV and the ASN(RDA) were not apparent to the committee.

-

Acquisition and engineering execution—operational concept and requirements development. The fleet can provide valuable feedback on the operational utility of assets being acquired by examining them in exercises and experiments. Thus, initial releases or prototypes of systems should be provided to the fleet as early as possible for this purpose. The new Sea Trial instruction from the CFFC appears to be a vehicle to encourage this process.

-

Interaction among all functional areas. All functional areas must interact effectively to provide speed to capability. Capability needs must be specified, mapped into programs with the appropriate priorities and resourcing, realized through acquisitions, and refined through operational application—all in a timely and flexible manner. As discussed for the acquisition functional area above (Section 7.3.2.3), greater speed to capability is necessary, particularly that pertaining to applying information technologies.

7.3.3.2 Means to Improve the Interactions

Making the individual cross-functional interactions and the entire set of interactions work effectively is in good part a matter of governance—giving parties the responsibility and authority to make the interactions and the whole process work. In this regard, the interaction between program formulation and resource allocation and acquisition and engineering execution is considered first. As discussed above, these two sets of functions need to be more tightly coupled. The committee does not believe that its analyses allow it to make a recommendation for a unique solution to this issue. Rather, it proposes the options presented in the following:

-

Recommendation for the SECNAV, in conjunction with the CNO and the ASN(RDA): Develop a means to integrate more closely the Navy’s program-

-

formulation and acquisition functions, to ensure that adjustments in program execution are consistent with program intent and best serve the overall need of providing forcewide FORCEnet capability. Options to consider include establishing (1) a Programs-Acquisitions Coordination Board co-chaired by the VCNO and the ASN(RDA) or (2) a director of FORCEnet reporting to the VCNO and ASN(RDA). This recommendation envisions that the board or director (depending on which was chosen) would have a major role in carrying out the other recommendations pertaining to program formulation and resource allocation and to acquisition and engineering execution. (Recommendation 15)

The Programs-Acquisitions Coordination Board would have support from a dedicated staff in OPNAV and ASN(RDA). The board would meet regularly, and the staff would work on current issues on a daily basis. The director, FORCEnet, would be a Navy vice admiral6 and would have a dedicated staff similar to that for a board. The importance and enduring nature of the integration function addressed by Recommendation 15 means the director (or executive secretary of the board) should have a long tenure—6 to 8 years, for example, in contrast to the 2 or 3 years for typical senior assignments.

Recommendation 15 more tightly couples the two lower spheres—program formulation and resource allocation and acquisition and engineering execution—in Figure 4.1 in Chapter 4. The next matter is the coupling in of the upper sphere, the operational component. In this regard, the committee recommends the following:7

-

Recommendation for the CNO: Charter CFFC to provide periodic assessments of the state of realizing FORCEnet capabilities. The review would include the following: the status and plans for concept development and experimentation for each of the Sea Power 21 pillars and FORCEnet, the current understanding of the set of capabilities required in the fleet, recommended changes in programs to align them better with this set of capabilities, and opportunities for employing acquisition prototypes in naval and joint experiments and exercises. NETWARCOM would provide the staff support to the CFFC in preparing this assessment. (Recommendation 16)

Beyond these governance measures, there is also a set of “forcing functions” that can be used to drive the implementation process. The intent of these forcing functions is to promote both speed to capability and breadth of capability through a spiral development process. To this end, the committee recommends the following:

-

Recommendation for the CNO, in conjunction with the ASN(RDA): Establish a set of FORCEnet goals to be realized by specified dates in order to drive the implementation process. Examples of these goals include the provision of specified bandwidth increases and networking capabilities to the fleet, the achievement of designated joint maritime and air situational-awareness capabilities, and the achievement of FORCEnet compliance (or phaseout) for a specified set of legacy systems. Goals could also be of a directly operational nature—for example, the ability to destroy a given class of targets within a stated number of minutes after the targets emerge from hiding. (Recommendation 17)

Further detail and more wide-reaching plans are also necessary to drive the implementation process. In this regard, the committee recommends the following:

-

Recommendation for the CNO, in conjunction with the ASN(RDA): Direct the preparation of an annual FORCEnet master plan for their review. The plan should lay out milestones—with an emphasis on near-term deliverables—for obtaining key FORCEnet capabilities in terms of operational concepts and systems deployment. The purpose of this plan would be to ensure senior visibility in this area and senior scrutiny of FORCEnet activities and consequent motivation for conducting these activities.8 (Recommendation 18)

7.4 FORCEWIDE PERSPECTIVE FOR MATERIEL DEVELOPMENT

As repeatedly stated, FORCEnet applies to the whole naval force—weapons, sensors, command-and-control systems, communications, and so forth. All of these elements relate to one another in network-centric operations. Thus, the naval force must be designed as a whole—but this does not mean a “grand design” in the sense of traditional systems engineering. The enterprise is far too complex and continual in its development and evolution for that to be possible. Rather, the “lighter touch” of treating the naval force as a complex system applies. This means defining the boundaries (“invariants”) that divide the force elements into their major components, broadly partitioning functionality among

those components, and establishing interfaces to allow these components to interact with one another. This specification is not permanently fixed, but it will evolve slowly over time, whereas the technologies used within the components can change rapidly with time.

The challenge of constructing a complex system requires that the necessary architectures must be developed. This does not mean that further development of the naval force should wait several years until a fully detailed architecture is prepared. Rather, the architectural approach is evolutionary in terms of detail. It is broadly filled out to start, and then the more detailed pieces are developed as necessary, and all of these pieces are evolved slowly over time as needed.

Required in conjunction with the architectures are the following: compliance mechanisms to ensure that the architectures will be applied in program execution, systems engineering processes to relate the architectures to detailed design and development, and integration testing to examine whether the system components actually do interact in the manner intended. The sections below cover this set of subjects.

7.4.1 Architecture Development and Compliance

There are two major architectural efforts pertinent to overall FORCEnet capabilities—(1) the FORCEnet architecture, developed by SPAWAR,9 and (2) the open architecture for combat systems developed by NAVSEA. Volume I of the SPAWAR architecture is primarily a high-level survey of military systems that would form components through which the FORCEnet capabilities are realized. Volume II is a list of almost 300 mandated standards applying principally to the information infrastructure that compliant systems must satisfy. While Volume I generally recognizes the extent of FORCEnet’s applicability, neither volume adequately defines the architectural boundaries or invariants, nor provides mechanisms for allocating functionality among the components. In general, the committee did not gain an understanding from the architecture documents of how the pieces described fit together (beyond FnII connectivity) to provide the overall FORCEnet capabilities.

Working in conjunction with NAVSEA and NAVAIR, SPAWAR is developing a process for assessing compliance of the EXCOMM-directed current systems baseline with the FORCEnet architecture. Generation and assessment of the baseline represent a sizable effort. Given the limited nature of the current archi-

tecture, this assessment will not address matters of overall architectural structure, but it should lead to understanding about the systems changes necessary to enhance information exchange among naval systems.10

The NAVSEA open architecture strongly reflects the ideas of invariant boundaries and functional partitioning, although the committee is concerned that the number of boundaries being established could be difficult to maintain.11 The open architecture represents an important advance in combat systems architecture, and its general design approach is applicable to the FORCEnet architecture as a whole. NAVSEA plans to incorporate the combat systems open architecture into a substantial portion of the fleet by 2008. This effort should establish a modern software architecture that facilitates the maintenance and upgrading of software and allows combat systems to share information more readily with external systems. However, in neither the SPAWAR nor the NAVSEA work reviewed did the committee see a technical discussion of how the FORCEnet and open architectures relate to one another. That understanding is necessary for the combat systems to interface with the external systems.

As a consequence of the preceding observations, the committee recommends the following:

-

Recommendation for the CNO and the ASN(RDA): Take measures to strengthen the FORCEnet architecture in terms of its ability to represent overall structural relationships among force components. To this end, the CNO and ASN(RDA) should designate NAVSEA, drawing on its open architecture experience, as having a major role in developing the FORCEnet architecture, particularly as pertains to its representation of invariant boundaries and the ability to allocate functionality.12 Furthermore, SPAWAR and NAVSEA should be directed to specify the technical interrelationship between the FORCEnet architecture and the combat systems open architecture. (Recommendation 19)

The FORCEnet Compliance Checklist,13 developed under the lead of the N6/ N7, lists standards (like those in Volume II of the SPAWAR architecture) that must be obeyed and criteria that must be met in the areas of human–systems

|

10 |

The high-level first-phase assessment is planned for completion by September 30, 2004. It is possible that the second-phase assessment planned to follow that will get into matters of functional allocation through the examination of mission threads. |

|

11 |

Naval Surface Warfare Center. 2003. Open Architecture Functional Architecture Definition Document, Version 2.0, November. For a general discussion of the open architecture initiative, see CAPT Richard T. Rushton, USN, Office of the Chief of Naval Operations (N76); Michael McCrave, ANTEON International Corporation; Mark N. Klett, Klett Consulting Group, Incorporated; and Timothy J. Sorber, Klett Consulting Group, Incorporated, 2004, Open Architecutre, The Critical Network Centric Warfare Enabler, Second Edition, Department of the Navy, Washington, D.C., June 29. |

|

12 |

Some first-order considerations for defining boundaries are given in Chapter 5. |

|

13 |

The version of February 1, 2004, was reviewed by the committee. |

integration, spectrum management, information assurance, and joint interoperability. While similar in purpose, a different philosophy is indicated in the Net-Centric Checklist14 prepared by the ASD(NII). It focuses on capability, whereas the OPNAV checklist focuses on the “what,” without reference to the need for a capability. The ASD(NII) checklist is intended to guide and aid the understanding of the design philosophy in system development, whereas the OPNAV checklist gives artifacts that have to be included in the system. The committee prefers the ASD(NII) approach because it should lead to a better understanding of the need for and qualities of the system design. The committee thus recommends the following:

-

Recommendation for OPNAV: Adopt the Net-Centric Checklist of the ASD(NII) in place of the OPNAV FORCEnet Compliance Checklist, adapting it if necessary to accommodate specific aspects of naval warfare. This design guidance, together with a focus on architectural boundaries, should help promote the development of FORCEnet architectural products. (Recommendation 20)

7.4.2 Systems Engineering and Integration Testing

Systems engineering is a process for allocating functionality to subsystems that are bounded by a system architecture, to maximize the effectiveness of the overall system in the set of missions that it is intended to execute. The complexity of the system providing FORCEnet capabilities makes developing and executing a FORCEnet systems engineering process a great challenge. While the principles of traditional systems engineering apply, the FORCEnet process must be expansive in its breadth, with recognition that the complex system will continually develop and evolve.

The systems commands have a long history of systems engineering practice, but in the briefings and other material presented to it, the committee did not see evidence of the major commitment required to meet the FORCEnet systems engineering challenge. SPAWAR is designated as the FORCEnet chief engineer, but the scope of that position is much narrower than the extent of the systems engineering function envisioned by the committee. Thus, the committee recommends the following:

-

Recommendation for the ASN(RDA), with the support of the systems commands and the relevant PEOs (primarily the PEO C4I & Space and PEO IWS): Develop the capability necessary to effect FORCEnet systems engineering. Very high standards, commensurate with the challenge, should be set for the

-

systems engineering staff, who can come from the systems commands, program offices, and outside sources, as necessary. This systems engineering capability would work directly in support of any organization developed to integrate the Navy’s program formulation and acquisition functions more closely (as discussed above in Section 7.3.3.2). (Recommendation 21)

On the basis of the experiences of its members in analyzing and developing large-scale systems, the committee recommends the following:

-

Recommendation for the ASN(RDA), the systems commands, and the relevant PEOs (primarily the PEO C4I & Space and PEO IWS): Pay particular attention to the following in establishing the FORCEnet systems engineering capability:

-

Instituting a change management authority responsible for the full set of FORCEnet functional partitions and standards. The decisions of this authority will affect a broad range of naval programs, unprecedented in any prior DOD systems engineering. This authority is key to maintaining the integrity of overall FORCEnet capabilities.

-

Providing for the frequent delivery of system capability (e.g., in 6-month increments). This will reinforce the value of the systems engineering process and is in keeping with the need for evolutionary development (discussed above, e.g., Section 7.3.2.3).

-

Achieving a mission focus in the analysis and allocation of functionality. For example, each mission can be characterized by a few key variables (e.g., battle force tracking and identification times in antiair warfare) that should be optimized in system design.

-

Establishing a rigorous process, independent of individual programs, for recommending the future course of legacy programs—phaseout, retention as is, upgrading, or merger into another program—based on the mission utility of each program.

-

Establishing means, involving both process and technology development, to recognize and deal with the vulnerabilities and fragilities that could cause significantly degraded overall capabilities. (Recommendation 22)

-

The last item in Recommendation 22 represents a particular challenge for complex systems, since their complexity—and in the case of FORCEnet, its unprecedented scope—means that there can be unknown, catastrophic failure modes, much more so than in traditional large-scale systems. Network control, distributed information management, and information assurance are three matters warranting particular attention in this regard for FORCEnet implementation.

Even in the case of a well-architected system with a proper systems engineering process, unanticipated integration difficulties can still occur when the overall system is assembled from its components. Integration testing is thus

required to detect and correct such problems. NAVSEA has provided this capability quite effectively for carrier battle groups through the distributed engineering plant. That capability must now be extended to the FORCEnet case. In fact, this capability could also be applied earlier in system development, to provide an exploratory environment for concept development. Thus, the committee recommends the following:

-

Recommendation for the ASN(RDA), in conjunction with the systems commands and the relevant PEOs (primarily the PEO C4I & Space and PEO IWS): Develop a FORCEnet DEP by generalizing the concepts and approaches used in the current DEP. Since the ongoing joint distributed engineering plant effort does not appear adequate to meet FORCEnet needs (e.g., in terms of scale), the Navy should play a lead role in realizing an extended JDEP by first extending the Navy DEP. (Recommendation 23)

7.5 INTEGRATION WITH JOINT DEVELOPMENTS

All recent U.S. combat operations have been joint, and operations will likely only become more so in the foreseeable future. The Navy and Marine Corps are committed to operating as part of a joint force. This viewpoint is made clear in official naval documentation15 and was expressed by numerous briefers to the committee.

Joint developments refer to the full set of functional areas shown above in Figure 7.1, when taken to apply to all Services and the joint community; the sections below are organized by these three sets of functional areas. Joint developments in these areas are currently in a state of great flux. Policies and processes affecting all areas have recently undergone significant modification, with further refinements being very likely. This flux poses both a challenge and an opportunity for the Naval Services. On the one hand, they will have to keep abreast of the changes and understand their implications for the naval forces. On the other hand, the challenges confronting the DOD as a whole as it seeks to prepare for future environments and institute network-centric capabilities are much the same as those facing the Naval Services, although the DOD’s are larger in scope. Thus, a successful FORCEnet implementation strategy can be the model for realizing network-centric capabilities across the DOD.

7.5.1 Operational Concept and Requirements Development

The committee offers the following observations about the functional areas of operational concept and requirements development pertaining to joint operations:

-

There is no set of future concepts for joint operations with adequate detail to inform and guide the Navy and Marine Corps in developing their concepts for participating in joint operations. Joint efforts to date, based on JCIDS, have been largely concerned with very broad conceptual development. The Joint Staff recently initiated work on a set of Joint Integrating Concepts that may provide the required specificity.

-

The JFCOM joint experimentation process is beginning to transition from being based on JFCOM-originated concepts focused at the operational level of war to becoming a broader process more widely serving the needs of the joint community and Services. Further progress in this direction is necessary, with particular attention on the tactical level of warfare, given the growing joint interaction at that level evident in recent conflicts. In participating in JFCOM experimentation activities, the Navy and Marine Corps need to keep their activities focused so that they do not become overwhelmed by the much greater JFCOM experimentation resources.16

-

While JFCOM is the executive agent for joint experimentation, the regional combatant commands are becoming an increasing focus for joint concept development and experimentation. The fleet commands are a natural vehicle for interacting with the combatant commands in this regard, as has been the case, such as in the interaction of the Pacific Fleet and its components with the PACOM.

-

The derivation of capabilities required by joint forces (and likewise their naval components) is not grounded in the necessary operational and technical analyses. For example, presumed network-centric operational concepts at the tactical level could require network availability and latency that envisioned systems are not technically capable of providing. Furthermore, even if the technical capabilities appear adequate, operational circumstances could lead to degradation in network capabilities. Without the necessary analyses and plans for dealing with the degradations, significant unanticipated shortfalls in deployed capability could well result.

On the basis of the preceding observations, the committee recommends the following:

-

Recommendation for NETWARCOM, NWDC, and MCCDC: Continue to work with JFCOM to broaden its experimental perspective, with particular emphasis on joint operations at the tactical level. If necessary for these organizations to maintain focused commitment in the face of far larger JFCOM resources, the CFFC, and the Commanding General, MCCDC, should provide guidance on the issues to be addressed and the partitioning of naval involvement in JFCOM, regional combatant command, and Service concept development and experimentation activities. (Recommendation 24)

-

Recommendation for the fleet commands and MEFs: Build on current interactions with regional combatant commands in order to grow the relationship between naval and joint concept development and experimentation. This means ensuring both that naval concepts are properly embodied in joint concepts and that they reflect the needs of the joint concepts. Combatant command exercises should be used as a principal vehicle for exploring and refining the concepts. This responsibility could require that the fleets devote more resources to concept development (analogous to a point made earlier in Section 7.3.2.1). (Recommendation 25)

-

Recommendation for NETWARCOM and MCCDC, with technical support from such organizations as SPAWAR and ONR: Undertake a series of naval mission-based analyses to understand the technical limits to achieving network-centric operational concepts and identify approaches for dealing with potential operational degradations in network capabilities. Such analyses should indicate where reliance on more “traditional” capabilities (e.g., the use of localized versus distributed services) may still be necessary, and where increased attention to network path diversity and node heterogeneity is needed to reduce network vulnerability. These results should be shared with other Services and the joint community to increase the understanding of the limits on joint operations.17 (Recommendation 26)

7.5.2 Program Formulation and Resource Allocation

Two topics are considered in this section: (1) matters of broad capabilities definition, prioritization, and resourcing; and (2) the synchronization of naval programs with joint programs providing network-centric capabilities.

7.5.2.1 Capabilities Definition, Prioritization, and Resourcing

The traditional defense planning process has been based on requirement statements and corresponding programs developed by the Services. The Joint Defense Capabilities Process instituted by the SECDEF in October 2003 seeks

instead to establish a process that recognizes from the outset the capability needs for joint warfighting, as determined by the combatant commanders, and provides a means for resourcing those needs. Since the process is in the midst of its first application as of this writing, it is too early to assess what its consequences are. However, if the process is successful in meeting its objectives, there is one clear implication for the Navy and Marine Corps (and other Services): namely, those programs that most contribute to joint warfighting and best serve the needs of the combatant commanders will fare most successfully in the budget progress.

The JCIDS process, established by the CJCS in June 2003, has motivations similar to those of the SECDEF process just noted. The JCIDS process is intended to define and prioritize the capabilities needed for joint operations and to review how well individual programs will contribute to joint operations. While several decisions relating to individual programs have been made, the JCIDS process has, in its year of operation, yet to produce prioritized statements of required capabilities.

Consideration of the SECDEF and CJCS initiatives described above leads the committee to recommend the following:

-

Recommendation for the N6/N7 and the DCMC(PP&O): Work to articulate clearly how FORCEnet capabilities pertain to joint operations and satisfy the needs of combatant commanders. In the context of the Joint Defense Capabilities Process and JCIDS, this line of argument will strengthen programs providing FORCEnet capabilities in the budget process. While assertions of the joint nature of FORCEnet capabilities have frequently been made by the Navy and Marine Corps in general terms, the committee has not seen any detailed analyses working through the arguments. (Recommendation 27)

-

Recommendation for the fleet commands and MEFs: Work with the combatant commands to which they are assigned in order to understand and feed into the naval requirements process the capabilities needed by the combatant commands from naval forces. The CFFC, and the Commanding General, MCCDC, would act as the intermediaries for feeding this information from the fleets and MEFs into the program planning processes of the Navy and Marine Corps. (Recommendation 28)

7.5.2.2 Synchronization of Naval Programs with Joint Programs

The joint programs under consideration are those that will provide a significantly enhanced GIG over the next several years—e.g., the TSAT system, JTRS, the NCES program, and companion information-assurance programs. The matter confronting the Navy and Marine Corps (and other Services) is one of balance. On the one hand, the GIG programs promise great increases in capability in such areas as communications bandwidth and software services. On the other hand, there are significant risks—for example, TSAT has both technical and budgetary

uncertainties, and NCES envisions a services-oriented architecture of unprecedented scope. The Services are thus faced with two issues: (1) how much to rely on capabilities developed under the GIG umbrella in lieu of their own capabilities, and (2) how much to commit now to complementary programs necessary to take advantage of joint GIG programs (e.g., building the ship terminals required for TSAT connectivity, developing NCES-reliant applications).

The Navy has shown a significant awareness of GIG programs and the related issues. The PEO C4I & Space has described benefits, challenges, and options available to the Navy in accommodating GIG capabilities, and ONR has initiated science and technology programs to address naval-unique GIG needs (e.g., ship antennas, maritime battlespace pictures). However, the committee has not seen a strategy articulated at the overall naval program and resource level for relating to joint GIG capabilities. Such a strategy appears warranted, given the capabilities that the joint programs can bring and the substantial naval program costs that could be involved.

On the basis of the discussion above, the committee recommends the following:

-

Recommendation for the N6/N7 and the Marine Corps Director for C4I: Adopt a prudent course with respect to joint GIG programs, endorsing the further development of these programs but also requiring a clear and continuing assessment of their technical and programmatic progress. In this context, the N6/N7 and the Director, C4I, should clearly understand the limits of applicability of network-centric capabilities, especially at the tactical level (as noted above in Section 7.5.1). (Recommendation 29)

-

Recommendation for the N6/N7 and N8, and the DCMC(P&R): Articulate programmatic strategies, updated on an annual basis, for leveraging progress and accommodating developments in joint GIG programs. This strategy should lay out approaches for developing the necessary complementary naval capabilities (e.g., terminals, antennas) and describe technical and programmatic alternatives corresponding to the status of joint programs—that is, whether they have remained on schedule, slipped, or failed to meet their objectives. The strategy should also indicate how to leverage joint GIG capabilities as they become available. While some such capabilities will not be deployable for many years (e.g., TSAT), others will be available in the near term (e.g., initial releases of NCES and Horizontal Fusion services). (Recommendation 30)

7.5.3 Acquisition and Engineering Execution

The Naval Services should participate actively with joint GIG programs during their execution for two reasons. First, the Naval Services have specific expertise that they can bring to the programs to aid their execution. Current examples of this are SPAWAR’s participation in NCES and information assur-

ance developments. Second, the needs of naval (and other Service) missions must be kept constantly in mind as design decisions and trade-offs are made during program execution. TSAT provides a good example of a case in which significant design evolution will likely take place, given the complexity anticipated for the overall system and the fact that the program is in its early stages now. The Navy is selectively involved in joint GIG programs at the present time. To underscore the importance of this involvement, the committee recommends the following:

-

Recommendation for the ASN(RDA), with support from the PEO C4I & Space, PEO Space Systems, SPAWAR, and MARCORSYSCOM: Track and provide input to the technical development of joint GIG programs to ensure that as these programs evolve, they continue to satisfy naval needs. This objective is best accomplished through naval participation in the programs. The ASN(RDA) should build on current naval participation to ensure that the involvement remains substantive and is across all major GIG programs. The ASN(RDA) should also see that the proper operational perspective (e.g., through the involvement of NETWARCOM) is brought to bear in this activity. (Recommendation 31)

The ONR will need to provide some additional technological solutions even if GIG programs proceed as planned. The GIG will not fulfill some FnII needs, such as communicating with submarines at speed and depth. Furthermore, since NCES as currently envisaged assumes continuous communications connectivity, its use requires some mixture of antenna technology and alternative relay paths to overcome antenna blockages that interrupt connectivity. Fully exploiting enterprise services in a naval context will require considerable exploration and potential technology development. As a consequence of these observations, the committee recommends the following:

-

Recommendation for ONR: Explore and develop technologies to address naval-unique problems in the GIG context. Areas to be addressed include solving the antenna blockage problem, managing the Navy’s inevitably limited bandwidth, connecting submarines at speed and depth to the network, providing alternative communications paths such as high-altitude airborne relays, exploiting the promised enterprise service capabilities of the GIG in the naval context, and constructing consistent maritime battlespace pictures. (Recommendation 32)

A number of policies with related technical documentation (e.g., the GIG architecture) have been instituted, primarily by the ASD(NII), to guide DOD realization of network-centric capabilities. These policies refer to network standards and security, approaches to making data widely available, and use of enterprise software services. In addition, the net-centric review process was initiated early in 2004 by the ASD(NII) to assess the degree to which Service programs are satisfying net-centric compliance criteria and to recommend funding based on the

degree of compliance (i.e., reduction or termination in funding for those programs faring poorly against the criteria). These policies and compliance criteria will constrain naval programs, but at the same time they will provide significant external leverage for achieving FORCEnet objectives—that is, realizing network-centric capabilities within the naval forces. The committee thus recommends the following:

-

Recommendation for the N6/N7, the ASN(RDA), and the MARCORSYSCOM: Fully impose the net-centric criteria mandated by the ASD(NII), in the development and execution of naval programs, subject to any necessary refinement of these criteria. Since the criteria are in their initial use now, the N6/ N7, the ASN(RDA), and MARCORSYSCOM should work with the ASD(NII) to refine these criteria as necessary, prior to their full imposition. The use of these criteria will further strengthen related internal policies of the Navy and Marine Corps. Furthermore, if the ASD(NII) net-centric reviews gain strong influence in the DOD budget process, meeting the criteria will be necessary to ensure adequate funding of programs. (Recommendation 33)

The GIG architecture refers primarily to networks and enterprise services, and in operational terms has not been much concerned with the specifics of military missions. Numerous additional architectural developments are underway in the Services, combatant commands, and combat support agencies referring to the more specific concerns of those organizations. The question is how all of these architectures relate to one another. The Navy is involved in limited efforts with other Services to understand such relationships—for example, SPAWAR funding and participation in Air Force and Army architecture development, and NETWARCOM participation in the Joint Rapid Architecture Experimentation initiative promoting horizontal interoperability among the Service’s next-generation tactical architectures. While these efforts are useful, the committee believes that more-comprehensive approaches to architectural integration are necessary since, without adequate integration, the overall vision of a network-centric U.S. military force will not be realized. The committee thus recommends the following:

-

Recommendation for the N6/N7 and the ASN(RDA):18 Work with OSD and the other Services to develop a better understanding of, and eventually to develop guidelines and principles for, how the numerous architectures being developed in the DOD can be effectively integrated. Particular attention is neces-

|

18 |

If a director of FORCEnet were appointed as discussed in Section 7.3.3.2, that individual would be the appropriate party to lead naval efforts in effecting this and the previous recommendation. |

-

sary at the tactical level of warfare, since architectural development of the GIG has not explored that level to a significant extent. The N6/N7 and the ASN(RDA) would be supported by SPAWAR, NETWARCOM, and MARCORSYSCOM in this work. Interaction with the combatant commands (particularly JFCOM and STRATCOM) and combat support agencies (particularly the Defense Information Systems Agency) would also be required. (Recommendation 34)