3

Joint Capability Development and Department of Defense Network-Centric Plans and Initiatives

3.1 INTRODUCTION

Use of FORCEnet … facilitates integrated Naval Forces and operations that are fully interoperable with the other joint forces. It will focus on creating information networks with new levels of connectivity and integration, which will integrate the force into a joint information network.1

The leadership of the Navy and Marine Corps is committed to providing “flexible, persistent, and decisive warfighting capabilities as part of a joint force.”2 At the same time, leadership in OSD is pressing the military departments and the Services to become more responsive to OSD’s and combatant commanders’ priorities for developing warfighting capabilities and implementing network-centric operations and processes.3 This urging has resulted in the OSD and the Joint Staff’s changing, during 2003, all higher-level guidance relevant to FORCEnet implementation. The combination of the naval leadership’s commitment to joint warfighting, which includes coalition operations with allies and security partners, and the broader DOD leadership’s commitment to strengthening jointness and

developing processes more responsive to combatant commanders’ needs, affects all aspects of FORCEnet implementation: namely, requirements prioritization and acquisition, concept development and experimentation, testing, and training. For FORCEnet to fulfill its intended function, it also must integrate into the broader DOD information infrastructure represented by the GIG. This chapter addresses the changes in broader DOD joint capability development and network-centric plans and initiatives that have direct implications for a FORCEnet implementation strategy.

3.2 REQUIREMENTS PRIORITIZATION AND ACQUISITION

3.2.1 Defense Planning Process

The Secretary of Defense (SECDEF) has implemented a new Defense Planning Process to provide the highest-level guidance within the DOD on resource prioritization and programming across the department.

In March 2003, the SECDEF commissioned a study led by former Undersecretary of Defense for Acquisition, Technology, and Logistics, E.C. “Pete” Aldridge, Jr., to provide streamlined processes, alternative functions, and organizations to better integrate defense capabilities in support of joint warfighting objectives.4 The study found that:

-

Services dominate the current requirements process, focusing on Service programs and platforms rather than on the capabilities required to accomplish combatant command missions; this situation results in an inaccurate picture of joint needs and an inconsistent view of priorities and acceptable risks across the DOD.

-

Service planning does not consider the full range of solutions available to meet joint warfighting needs; alternative ways to provide equivalent capabilities receive inadequate attention, particularly if the alternative solutions reside in a different Service or defense agency.

-

The resourcing function focuses the efforts of senior leadership on fixing problems at the end of the process, rather than its being involved early in the planning process.

-

OSD programming guidance exceeds available resources and does not provide realistic priorities for joint needs, resulting in a program that does not best meet joint needs or provide the best value for the nation’s defense investment.

In October 2003, the SECDEF issued a memorandum directing the establishment of a Joint Capabilities Development Process to examine, on the basis of the Aldridge study, major issues in support of the development of the 2006–2011 programs and budget.5 The new process differs from the current process in the following respects:

-

Combatant commanders are assigned a much larger role in shaping the defense strategy articulated in the Strategic Planning Guidance (SPG), which replaces the Defense Planning Guidance and focuses on strategic objectives, priorities, and risk tolerance, rather than on programmatic solutions. The SPG initiates the planning process and dictates those areas in which joint planning efforts must focus.

-

An Enhanced Planning Process (EPP) supports the assessment of capabilities for meeting joint needs; these are identified primarily through combatant command operational plans and operating concepts. The Services and the OSD retain responsibility for identifying nonwarfighting needs.

-

A forthcoming document, Joint Programming Guidance, will reflect decisions made in the EPP and provide fiscally executable guidance for the development of programs, with the intent of simplifying the remainder of the resourcing process and reducing the scope and level of effort required for program and budget reviews.

The new Defense Planning Process is immature, and the initial results will not be evident until the fall of 2004 (some months after this writing). Issuing the SPG took longer than anticipated, and the EPP is ongoing. However, the intent of the SECDEF to produce fiscally feasible Joint Programming Guidance directing the Services to acquire specific capabilities is clear.

3.2.2 Joint Capabilities Integration and Development System

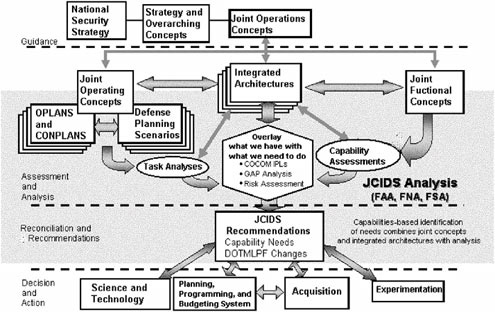

The new Joint Capabilities Integration and Development System (JCIDS)6 replaces the former requirements-generation system with a process that emphasizes joint concepts and, using those concepts, capabilities-based planning. The Joint Staff led the development of the JCIDS approach, and it preceded the Aldridge study, but its motivations are similar to those of the study. As its name implies, the new process is intended to provide substantive improvements in interoperability among components of joint forces in future battles. Figure 3.1 depicts the JCIDS process as it was envisioned.

FIGURE 3.1 The Joint Capabilities Integration and Development System’s (JCIDS’s) top-down process for identifying capability needs. NOTES: OPLANS, operational plans; CONPLANS, concept plans; COCOM, combatant command; IPL, integrated priority list; FAA, functional area analysis; FNA, functional needs analysis; FSA, functional solutions analysis; DOTMLPF, doctrine, organization, training, materiel, leadership and education, personnel and facilities. SOURCE: CJCSI 3170.01C.

The JCIDS process alters the former requirements-generation system in order to emphasize capability needs rather than threat responses. It replaces Mission Needs Statements with Initial Capabilities Documents, and Operational Requirements Documents are replaced with Capability Development Documents and Capability Production Documents.

The JCIDS process applies to all acquisition categories (ACATs). All of the new capabilities documents are to be sent to a “gatekeeper” on the Joint Staff to determine whether they fit into various categories—being of interest to the Joint Requirements Oversight Council (JROC)7 (all ACAT 1/1A programs),8 having joint impact, requiring joint integration, or being independent—depending on the extent to which the gatekeeper deems the program to impact joint concepts and operations. Only those programs categorized as “independent” require no further joint certification. Functional capabilities boards are to analyze gaps and seams among those programs that have joint impact or require joint integration and therefore require joint certification. Though FORCEnet is not a program, FORCEnet-related programs will have joint impact and therefore will entail joint certification. This status will link FORCEnet development even more closely to DOD efforts to create joint battle management command and control (JBMC2) and the GIG.

3.2.3 Joint Battle Management Command and Control

The Deputy Secretary of Defense’s Management Initiative Decision 912 in early 2003 directed JFCOM to lead efforts to strengthen the organizing, training, and equipping of joint battle management command and control capabilities for combatant commanders.9 JBMC2 is deemed to consist of the processes, architectures, systems, standards, and command-and-control operational concepts employed by the Joint Force Commander. The JBMC2 effort is governed by a board of directors consisting of flag officers and chaired by JFCOM, with representatives from the combatant commands and Services in the core group, and a wider

|

7 |

Under the current process, requirements are matched against specific military needs at the Pentagon as the DOD develops its share of the president’s annual budget request. These requirements are vetted by the Pentagon’s Joint Requirements Oversight Council, a body that includes the vice chief of staff of each of the uniformed Services. The council has the power to approve or defer requirements. |

|

8 |

The ACAT designations (I, II, III, etc.) are established for all the military Services by DOD Instructions 5000.1 and 5000.2 and their Service-specific supplements. For additional information, see http://www.acquisition.navy.mil. Accessed July 24, 2004. |

|

9 |

Deputy Secretary of Defense. 2003. Management Initiative Decision 912: “Charter for Joint Battle Management Command Control (JBMC2) Board of Directors (BOD),” U.S. Department of Defense, Washington, D.C., January 7. |

group of advisers having responsibilities for affected programs. A JBMC2 roadmap is in preparation. The goal of the roadmap is as follows:

[to] develop a coherent and executable plan that will lead to integrated JBMC2 capabilities and interoperable JBMC2 systems that in turn will provide networked joint forces:

-

Real-time shared situational awareness at the tactical level and common shared situational awareness at the operational level;

-

Fused, precise, and actionable intelligence;

-

Decision superiority enabling more agile, more lethal, and survivable joint operations;

-

Responsive and precise targeting information for integrated real-time offensive and defensive fires; and

-

The ability to conduct coherent distributed and dispersed operations, including forced entry into anti-access or area-denial environments.

This roadmap will be the vehicle for prioritizing, aligning and synchronizing Service JBMC2 architectural and acquisition efforts.10

The draft JBMC2 roadmap calls for plans to be complete by the beginning of 2006, followed promptly by “cluster” tests, presumably tied to joint mission threads such as joint close-air support. The roadmap addresses FORCEnet in the context of providing a single integrated maritime picture, with ashore network integration accomplished in 2008 and afloat network integration accomplished in 2010. However, the draft roadmap has only a placeholder for the detailed description of FORCEnet.11 From the description of FORCEnet in the draft roadmap, it is not clear what influence the JBMC2 board of directors will attempt to exert on the development of the FnII.

3.2.4 Joint Lessons Learned from Recent and Ongoing Operations

On the basis of lessons learned from operations and experimentation in determining defense priorities for capabilities development and programming, the new Defense Planning Process and JCIDS identify a greater role for combatant commands’ integrated priority lists. More directly, the global war on terrorism and the lessons and clear shortfalls evident in operations in Afghanistan and Iraq are becoming major drivers both for resource-allocation priorities and for the creation of processes that can respond faster to operational needs.

In conjunction with OIF, JFCOM positioned teams of analysts at the major joint command headquarters for the express purpose of gathering joint operational insights on a comprehensive scale as the operations unfolded, rather than collecting impressions following the operations. Based on these observations the commander of JFCOM testified:

The fundamental point is that our traditional military planning and perhaps our entire approach to warfare have shifted. The main change, from our perspective, is that we are moving away from employing Service-centric forces that must be de-conflicted on the battlefield to achieve victories of attrition to a well-trained, integrated joint force that can enter the battlespace quickly and conduct decisive operations with both operational and strategic effects. Joint Force Commanders today tell me that they don’t care where a capability comes from so long as it meets their warfighting needs. They also tell me that “it’s not the plan, it’s the planning.” They understand that the ability to plan and adapt to changing circumstances and fleeting opportunities is the key to rapid victory in the modern battlespace.12

The Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (CJCS) has directed the commander of JFCOM to carry out the following:

-

Aggregate key joint operational and interoperability lessons reported by combatant commands, defense agencies, and the Services during OIF and the war on terrorism;

-

Analyze, categorize, and prioritize these lessons, working with functional capabilities boards; and

-

Convey recommendations of materiel and nonmateriel approaches for remedies to shortfalls indicated by the lessons learned to the JROC as the basis for recommendations to the SECDEF.13

This effort is leading to the establishment of a permanent JFCOM organization on lessons learned (the Joint Center for Operations Analysis and Lessons Learned) linked to its requirements division (J8), which also chairs the JBMC2 board of directors. This organization will document joint lessons-learned efforts, produce proposals regarding program changes, and have designated agents track their implementation.14 The intention is to provide shortfall remedies to deploying forces rather than to have them learn similar lessons.

3.3 JOINT CONCEPT DEVELOPMENT AND EXPERIMENTATION

To ensure joint forces are truly interoperable and complementary in the future, the Sea Services will be fully engaged in Joint Concept Development and Experimentation (JCD&E).15

The Navy and Marine Corps have been coordinating their concept development and experimentation (CD&E) activities more closely over the past 5 years than they did before.16 Beginning in 2003, with the JFCOM Pinnacle Impact 03 and Unified Quest 03 experiments, they have increased their respective efforts to participate in JCD&E activities and in efforts to “showcase the utility of Naval concepts during other Services’ Title X war games.”17

3.3.1 Joint Concept Development

The JCIDS process calls for programs to be organized around the capabilities needed to execute joint concepts. The process (depicted in Figure 3.1) derives guidance from the National Security Strategy and amplifying documents. Ideally, from these sources come an overarching Joint Operating Concept and subordinate joint operating and functional concepts: these concepts would inform the development of integrated architectures as a basis for analysis and risk assessment in determining capability needs, and they would inform the resourcing and joint experimentation needed for assessment.

In November 2003, the SECDEF issued the “Joint Operations Concept,” (JOpsC) as the overarching document that contains the following:18

-

A description of how the Joint Force intends to operate within the next 15 to 20 years;

-

The conceptual framework to guide future joint operations and joint, Service, combatant command, and combat support defense agency concept development and experimentation; and

-

The foundation for the development and acquisition of new capabilities through changes in doctrine, organization, training, materiel, leadership and education, personnel and facilities (DOTMLPF).

The JOpsC includes a taxonomy of subordinate concepts, including joint operating concepts (JOCs), joint functional concepts, and enabling concepts (now termed joint integrating concepts). In this construct of concepts, “there is no hierarchy to operating, functional or enabling concepts—they must all inform and interrelate with each other.”19 The “Joint Operating Concept” describes the function of JOCs as follows: “focusing at the operational-level, JOCs integrate functional and enabling concepts to describe how a JFC [Joint Force Commander] will plan, prepare, deploy, employ and sustain a joint force given a specific operation or combination of operations.”20 The purpose of functional concepts, having the JOpsC and JOCs for their operational context, is to amplify a particular military function and apply it broadly across the range of military operations.

The DOD’s “Transformation Planning Guidance,” published in April 2003, had directed that “the CJCS, in coordination with Commander, JFCOM, will initially develop one overarching joint concept and direct the development of four subordinate JOCs: homeland security, stability operations, strategic deterrence, and major combat operations.”21 The JOpsC described the scope of these concepts and identified four initial functional concept categories of joint command and control: battlespace awareness, force application, focused logistics, and protection. A functional capabilities board for each of these categories (and a fifth recently added network-centric warfare category) serves both to articulate the functional concept and to certify programs deemed to have joint impact or to require joint interoperability. The Naval Operating Concept for Joint Operations aligns its concepts of Sea Strike, Sea Shield, Sea Basing, and FORCEnet with the Joint Vision 202022 concepts of precision engagement, dominant maneuver, full dimensional protection, focused logistics, and joint command, control, communications, computers, intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (C4ISR), from which the new functional capabilities categories were derived.

Combatant commands have been assigned the lead in writing the operating concepts (JFCOM: major combat operations, stability operations, joint forcible-entry operations; U.S. Strategic Command (STRATCOM): strategic deterrence; NORTHCOM: homeland security). The subordinate concept documents are in preparation and review, awaiting JROC approval. The Navy and Marine Corps are participating in the development of these concepts to ensure congruence between these concepts and the Naval Operating Concept for Joint Operations.

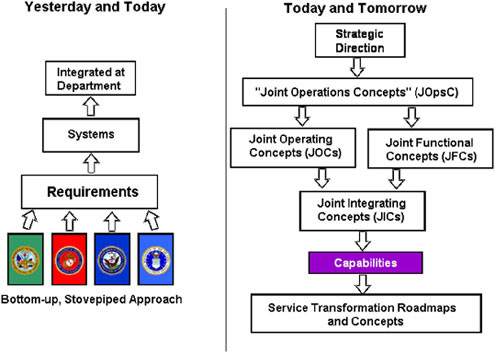

In its initial efforts to implement the JCIDS process, the Joint Staff found that it needed to establish a set of joint integrating concepts to derive integrated architectures from the operational and functional concepts. Figure 3.2 illustrates the latest approach for shifting from a bottom-up approach driven principally by the Services to a top-down approach driven principally by the OSD leadership and combatant commanders. Noteworthy is that the chart indicates that both the bottom-up and top-down approaches coexist today, but that the top-down approach is intended to drive the Service transformation roadmaps and concepts in the future. Also notable is that settling upon a set of joint integrating concepts has proven a challenge. Two concepts selected for early development are those of undersea superiority (for which the Pacific Command (PACOM) would have the lead in writing the operational concepts) and sea basing (for which the U.S. Transportation Command would have the lead).

3.3.2 Joint Experimentation

The DOD’s Joint Experimentation Program began in May 1998 when the SECDEF designated the U.S. Atlantic Command (which became JFCOM in

FIGURE 3.2 Joint Staff approach for shifting from a bottom-up approach driven principally by the Services to a top-down capabilities-based methodology. SOURCE: U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff.

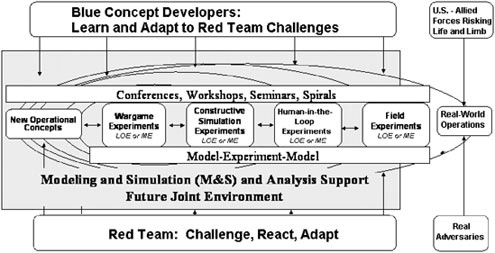

FIGURE 3.3 DOD’s concept of a continuous process of interactive experimentation for the joint experimentation process. NOTES: LOE, limited objective experiment; ME, mission execution. SOURCE: U.S. Joint Forces Command, Norfolk, Va.

October 1999) as executive agent for joint warfighting experimentation.23 In October 1998, the U.S. Atlantic Command established a Joint Experimentation Directorate (J9) to implement this responsibility. The intent was to create a continuous process of interactive experimentation, using methods depicted in Figure 3.3. The conception was to have a continuous process of concept exploration and development, beginning with papers and assessments by subject-matter experts, moving into more rigorous war gaming, then to detailed human-in-the-loop simulations, leading to field exercises and evaluation of concepts in actual operations, with subsequent events informing the previous ones.

Red teams were recognized as an essential feature of this activity. The OSD established a Defense Adaptive Red Team as part of the Joint Warfighting Program element retained by the Deputy Under Secretary of Defense for Advanced Systems and Concepts when Joint Experimentation Program funds were transferred to JFCOM. This team employs a wide variety of regional, country, and local-area expertise, in addition to selected retired military officers, to play the role of nontraditional adversaries in various DOD-sponsored games. JFCOM also established a red team as part of its J9.

The value of red teams increases with the rigor of the experiments; their use is essential for ensuring that wishful thinking does not color learning. Red teaming in general discussions is of limited use, however. The most ambitious use of red teams has occurred in the “opposition forces” at the Army’s National Training Center at Fort Irwin, California, which is becoming the hub of the Joint National Training Capability. To prepare forces for operations in Afghanistan and Iraq, the scenarios have changed to include forces dealing with stability and reconstruction operations, learning to identify village leaders, assessing and assisting in reconstruction with funding and other assistance, and identifying and defeating various classes of adversaries ranging from national resistance to jihadist elements. American-Iraqis play the roles of innocents and various classes of adversaries.

The conception of the experimentation process depicted in Figure 3.3 has yet to materialize. In striving to realize its vision, JFCOM has increasingly sought Service support for its efforts.

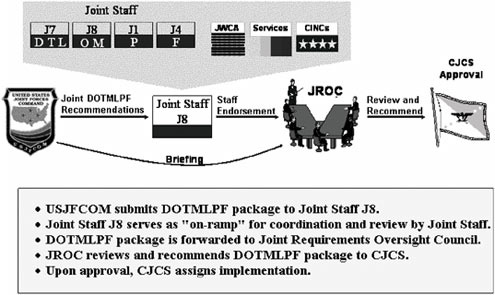

The initial focus of the Joint Experimentation Program was at the joint operational level, on future (7 to 15)-year joint concepts.24 The output of JFCOM experimentation was intended to be DOTMLPF recommendations to the JROC, as depicted in Figure 3.4. Upon JROC approval, these recommendations were to affect the development of joint capabilities, including Service programs.

In November 2001, the CJCS directed JFCOM to develop a Joint Experimentation Campaign Plan focused “on the development of a standing joint force headquarters model no later than the end of Fiscal Year 2004 and capable of implementation by all regional Commanders-in-Chief (CINCs) (regional combatant commanders) during FY05.”25 This directive resulted in essentially all of JFCOM’s joint concept and development experimentation effort being concentrated on the Standing Joint Force Headquarters (SJFHQ).

In November 2002, the CJCS revised his joint experimentation guidance:

The plan must incorporate a decentralized process to explore and advance emerging joint operational concepts, proposed operational architectures, experimentation and exercise activities currently being conducted by the Joint Warfighting Capabilities Assessment Strategic Topic Task Forces [run by the Joint Staff with Service participation], the combatant commands, the Services and Defense Agencies.26

FIGURE 3.4 The review and approval process for joint DOTMLPF. NOTES: J7, Director, Operations Plans and Interoperability; J8, Director, Force Structure, Resources, and Assessment; J1, Director, Manpower and Personnel; J4, Director, Logistics. SOURCE: U.S. Joint Forces Command, Norfolk, Va.

This guidance kept the SJFHQ as the highest priority, but it also directed coordination with combatant commands, Services, Joint Staff, and defense agencies, as well as the inclusion of the following:

-

Lessons learned from the war on terrorism;

-

Joint operations in an uncertain environment and complex terrain;

-

Fast-deploying joint command-and-control structures;

-

Concepts to provide warfighters at all levels with improved battlespace awareness, correlation and dissemination of mission-specific information, and more closely integrated intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance efforts and products;

-

Joint capabilities enabling the near-simultaneous, integrated, and synergistic employment and deployment of air, land, sea, cyberspace, and space warfighting capabilities, capitalizing on Service concepts and capabilities that enable forward joint forces and those based in the continental United States to deploy, employ, sustain, and redeploy in austere regions and antiaccess and area-denial environments.

-

Transformational concepts of the Nuclear Posture Review (involving global strike with conventional and special forces in addition to nuclear strike, as well as global information operations); and

|

BOX 3.1

NOTE: Emphasis in original. (The boldface items indicate priorities to be addressed in FY 2004 and FY 2005.) SOURCE: U.S. Joint Forces Command, Norfolk, Va. |

-

Current efforts to promote and develop regional component-commander-sponsored joint and multinational partnerships involving experimentation and capability-based modeling and simulation.

To implement this guidance, JFCOM J9 polled the combatant commands to obtain a sense of their priorities and coordinated with the Services to find more opportunities to explore concepts in Service war games. Polling the combatant commanders produced 308 items, which were aggregated into those illustrated in Box 3.1.27 The highlighted items indicate priorities that were to be addressed in FY 2004 and FY 2005.

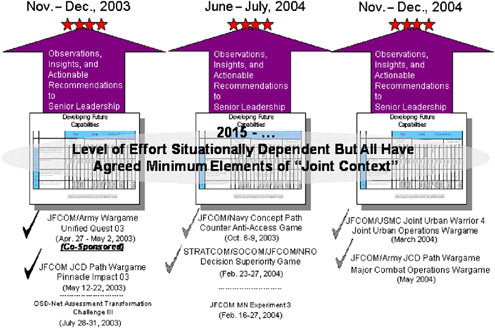

The JFCOM J9 intent was to use Service war games based upon a common set of joint scenarios to address the priority issues. Figure 3.5 illustrates the proposed plan for FY 2004.

The OSD and Commander of JFCOM tasked the Defense Science Board (DSB) to review the Joint Experimentation Program. In its Phase I report of September 2003, the DSB found: “Of particular importance is the need to reorient JFCOM’s experimentation focus from inward (largely about inviting others to participate in JFCOM events) to external (largely about participating in and influencing Service and combatant command experiments and related activities).”28Figure 3.5 illustrates JFCOM efforts to work with Services and other combatant commands. However, JFCOM’s approach has remained one of attempting to align Service and combatant command efforts to its own agenda as opposed to supporting other organizations in experimenting with a broader set of challenges. Also, JFCOM has had difficulty realigning the resources that it devoted to the SJFHQ. While more war-gaming effort has gone into examining a broader set of warfighting concepts, the bulk of JFCOM J9’s expenditures are related to the 2001 tasking to field SJFHQs to combatant commanders during FY 2005.

Aligning Sea Trial with JFCOM’s concept development and experimentation could easily engulf the Navy and Marine Corps CD&E efforts. JFCOM J9 has more than 400 people on its staff. The Navy Warfare Development Command (NWDC) has about 20 people with responsibilities similar to those of the J9 staff. While supporting JFCOM with a full-time liaison officer, the MCCDC is in a situation similar to that of the Navy.

3.4 JOINT TESTING—THE JOINT DISTRIBUTED ENGINEERING PLANT

System testing prior to deployment will be part of any FORCEnet implementation strategy. The joint battle management command and control roadmap calls for expansion of the Joint Distributed Engineering Plant (JDEP). JDEP is a DOD-wide facility that offers Service and joint engineering, integration, and test resources to provide system-of-systems environments that are battlefield-representative, in support of developer, tester, and warfighter requirements.29 Based on the Navy’s Distributed Engineering Plant (DEP) model, JDEP is a response to operational demands for sharing data and information among systems of systems assembled to conduct military operations. The JDEP vision is to improve the

interoperability of weapons systems, platforms, and command and control within and across the Services by providing the capability to create environments to support engineering, development, integration, testing, evaluation, and certification in a replicated battlefield environment, leveraging Service and joint combat system engineering and test sites. JDEP’s goals are as follows:

-

To create a capability to integrate DOD and industry laboratories, test sites, and facilities to address and resolve weapons system interoperability issues for warfighters, system developers, and testers; and

-

To support users in selecting, accessing, and integrating simulations and range systems, using supporting tools, under a set of common standards and procedures.

Although not a new concept, conducting events on a joint level to synchronize efforts, resources, and assets across the Services by critical mission areas is a new approach. The JDEP technical framework comprises the components of a JDEP configuration, the interfaces, and the guidance on how to configure and apply the components to meet user needs. This technical framework is critical to cost-effectively federating simulation, hardware- and software-in-the-loop, and systems across multiple communities. Because industry is a key participant in these activities, the JDEP technical framework, including the high-level architecture (HLA), is based on industry standards, and it is being implemented using standards-based commercial products wherever possible.30 Funds of $182 million for FY 2002–2007 are programmed for the JDEP.

Established in 2000, the JDEP program has principally supported air and missile defense events to date, but it is extending into other mission areas by working directly with acquisition programs as well as with functional capabilities boards. The OSD requires all new programs—for example, the aircraft carrier (CVN 21), the future destroyer, and the Joint Strike Fighter—to use the JDEP in order to obtain milestone B program approval.31

JDEP is encountering the challenge of finding exactly what technical, data, and application standard affect all current networking efforts.

3.5 JOINT TRAINING TRANSFORMATION

The Joint Training Transformation presents an opportunity for FORCEnet implementation. The objectives of the training transformation are as follows:32

-

To strengthen joint operations by preparing forces for new warfighting concepts,

-

To improve joint force readiness continuously by aligning joint education and training capabilities and resources with combatant command needs,

-

To develop individuals and organizations that intuitively think jointly,

-

To develop individuals and organizations that improvise and adapt to emerging crises, and

-

To achieve unity of effort from a diversity of means (drawn from Active and Reserve components of the Services and from federal agencies, international coalitions, international organizations, and state, local, and nongovernmental organizations).

Three capabilities form the foundation for the training transformation:

-

The joint knowledge development and distribution capability will develop and distribute joint knowledge via a dynamic, global, knowledge network that provides immediate access to joint education and training resources.

-

The joint national training capability (JNTC) will prepare forces by providing command staffs and units with an integrated live, virtual, and constructive training environment that includes appropriate joint context and that allows global training and mission rehearsal in support of specific operational needs. The thrusts for the JNTC are these:

-

Improved horizontal training—building on existing Service interoperability training,

-

Improved vertical training—linking component and joint command and staff planning and execution,

-

Integration training—enhancing existing joint exercises to address interoperability training in a joint context, and

-

Functional training—providing a dedicated joint training environment for functional warfighting and complex joint tasks.

-

-

The joint assessment and enabling capability will assist leaders in assessing the value of transformational initiatives with respect to individuals, organiza-

-

tions, and processes by evaluating the level of joint force readiness to meet validated combatant commander requirements.

The Web-based networks that the training transformation is expected to provide will be of potential value to FORCEnet implementation. The schedule for these Web-based networks includes the following milestones for training transformation:

-

Joint knowledge development and distribution capability milestones include:

-

An initial Web-based curriculum for joint military leader development by January 2004,

-

An initial Web-based delivery capability for joint individual education and training resources by February 2005, and

-

The transitioning of initial joint education and training prototype efforts to implementing organizations by March 2006, and to international coalition partners, international organizations, and nongovernmental organizations by October 2009.

-

-

JNTC milestones include:

-

Provision of a joint context with command, control, communications, computers, intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance to major Service training events and joint command and staff training events by October 2005;

-

Use of the joint training system to link lessons learned from military operations, joint training, experimentation, and testing to the development and assessment of joint operational capabilities by October 2005;

-

Demonstration of a deployable JNTC and mission-rehearsal capabilities by October 2007; and

-

Creation of an initial Web-based delivery capability for operational mission planning and rehearsal by October 2005.

-

-

Joint assessment and enabling capability milestones include:

-

Tracking of joint education and training experience of all DOD personnel by October 2005,

-

Linking of joint training to the Defense Readiness Reporting System network by March 2006, and

-

Ensuring that all DOD forces are trained prior to and during deployment by October 2007.

-

The DOD’s Management Initiative Decision 906 indicates levels of funding during the FY 2003–2009 period for the training transformation effort: $86.4 million for the joint knowledge development and distribution capability; $1,121.7 million for JNTC; and $118.9 million for the joint assessment and enabling capability. This effort will provide a common architecture for linking test and training ranges.

The major training centers to be linked during the FY 2003–FY 2005 period are as follows:33

-

U.S. Army National Training Center, Fort Irwin, California;

-

Joint Readiness Training Center, Fort Polk, Louisiana;

-

Fort Bliss Exercise Roving Sands training range, Fort Bliss, Texas;

-

U.S. Navy Fleet East training area, Norfolk, Virginia;

-

U.S. Navy Fleet West training area, San Diego, California;

-

U.S. Air Force Nellis test and training ranges, Nellis Air Force Base, Nevada; and

-

U.S. Marine Corps Twenty-Nine Palms range, Twenty-Nine Palms, California.

Future plans include linking training ranges worldwide and providing a deployable capability by October 2007.

3.6 GLOBAL INFORMATION GRID

OSD, and particularly the ASD(NII), has undertaken both policy and program initiatives to promote what they call “netcentricity.” These activities are centered on the concept of a GIG. They will both facilitate and constrain DON’s implementation of FORCEnet.

3.6.1 Policy Initiatives

Policy initiatives are intended to ensure interoperability and to promote a Services-oriented architecture. Table 3.1 lists some of the documentation related to these initiatives.

The Net-Centric Checklist, summarized in Table 3.2, will be used in OSD program reviews to ensure that the Services and combat support agencies support network-centricity. Several policy memoranda34 make clear the OSD’s commitment to this transformation. Programs will be classified according to their degree of conformity; nonconforming programs will be targeted for termination by prohibiting their further acquisition and deployment and by decrementing the funding for their maintenance.

TABLE 3.1 Key Documentation Related to the Global Information Grid (GIG)

|

Document |

Purpose |

|

Net-Centric Operations and Warfare Reference Model |

Serves as a reference for network-centricity in the development of Department of Defense (DOD) architectures and in DOD oversight processes—describes enterprise-level activities, services, technologies, and concepts. |

|

DOD Net-Centric Data Strategy |

Defines a vision for data management within the DOD, emphasizing visibility and accessibility. |

|

GIG Core Enterprise Services (CES) Strategy |

Defines each of the CES, describes the technical capabilities that will be delivered by each of the CES, and presents a strategy for the evolution of capabilities. |

|

Joint Technical Architecture, Version 6.0 |

Delineates mandatory standards and guidelines, lists emerging, network-centric standards and guidelines as reference material for acquisition. |

|

Net-Centric Checklist, Version 2.1 |

Serves as a guide to understanding network-centric attributes required for programs to move into the GIG network-centric environment. |

|

GIG Architecture, Version 2.0 |

Describes the GIG architecture. |

|

Transformational Communications Architecture (TCA) |

Describes the TCA. |

3.6.2 Components of the Global Information Grid

Table 3.3 describes the eight investment areas leading to the realization of the GIG. The first seven are programs. The eighth, Horizontal Fusion, is a portfolio of experiments and demonstrations managed by the ASD(NII).

Each of the seven development programs has one or more executive agents drawn from among the Services and combat support agencies. One risk, not shown in the table, is that funding for Service-managed programs must compete within their own Service and at the JROC.

3.6.3 Implications for FORCEnet

When fully implemented, the GIG will be capable of performing considerable “heavy lifting” for FORCEnet. Provided that DON buys suitable terminals and sites them properly, TSAT promises to provide T-1 level (1.5 Mbps) service to 1-foot apertures on the move, and much higher capacities to larger antennas. Optical exfiltration and backhauling of airborne surveillance data will free unmanned air vehicles from a line-of-sight tether to ships and will make possible

TABLE 3.2 Summary of the Net-Centric Checklist Used by the Office of the Secretary of Defense in Program Reviews for the Services and Combat Support Agencies

smaller ship crews by exploiting the data at combatant command headquarters and in the continental United States.

The GIG-BE will simplify the work of the Naval Computer and Telecommunications Area Master Station (NCTAMS) and the Network Operations Center System and reduce the load on satellite communications. JTRS will support force composability both through making the wideband networking waveform available to all forces and by interoperating with legacy radios. NCES promises to reduce nonrecurring cost in acquiring new software capabilities and to simplify the maintenance and operation of deployed systems. Joint command and control promises interoperability among Service command-and-control systems—a promise that the Global Command and Control System (GCCS) never quite kept.

|

Metric |

Source |

|

Net-Centric Operations and Warfare Reference Model (NCOW RM) compliance. |

NCOW RM, GIG Arch v2, IPv6 Memos (June 9, 2003, and Sept. 29, 2003) |

|

Transformational Communications Architecture (TCA) compliance. |

TCA |

|

Reuse of existing data repositories. |

Community-of-interest policy (to be determined). |

|

NCOW RM compliance. Data are tagged and posted before processing. |

NCOW RM, DOD Net-Centric Data Strategy (May 9, 2003) |

|

NCOW RM compliance. Data are stored in public space and advertised (tagged) for discovery. |

NCOW RM, DOD Net-Centric Data Strategy (May 9, 2003) |

|

NCOW RM compliance. Metadata are registered in DOD Metadata Registry. |

NCOW RM, DOD Net-Centric Data Strategy (May 9, 2003) |

|

NCOW RM compliance. Applications posted to the network and tagged for discovery. |

NCOW RM |

|

Access is assured for authorized users, denied for unauthorized users. |

Security information assurance policy (to be determined). |

|

Being network-ready is the key performance parameter. |

Service-level agreements (to be determined). |

The Distributed Common Ground/Surface Systems (DCGS) will make data from the sensors of all Services and agencies available in fused and actionable form.

The network-centric policies of the OSD provide external leverage for making new naval platforms network-centric. Nevertheless, the GIG presents challenges as well as opportunities for FORCEnet. Much of the GIG philosophy is based on a promise that communications bandwidth will no longer be a constraint. That assumption makes a transition to an enterprise architecture within thin clients (those with limited processing and storage capability) attractive. Experience in the commercial sector indicates that a transition to an enterprise architecture may increase communications traffic by several orders of magnitude. On the other hand, the committee heard that many major ships have very limited

TABLE 3.3 Components of the Global Information Grid

|

Component |

Description |

Availabilitya |

Issues/Risk |

|

Communications |

|

||

|

Transformational Satellite |

Optical crosslinks and unmanned air vehicle uplinks; high-performance extremely high frequency. |

After FY 2012 |

Major space program with new technology. |

|

GIG-BE |

Global fiber network. |

FY 2004 |

Terrestrial only. |

|

Joint Tactical Radio System |

Software-based radios for legacy waveforms and new networks. |

FY 2005–2007 for ground and air systems; FY 2009 for maritime systems. |

Delivery time of maritime capability. |

|

Crypto Xformation |

Packet encryption for black core. |

After FY 2005 |

Overhead. Converting ships to black routing. |

|

Services |

|

||

|

Network-Centric Enterprise Services |

Common services for entire Department of the Navy enterprise. |

FY 2008 |

Performance and scalability. Dependence on perfect communications. |

|

Command-and-Control Systems |

|

||

|

Distributed Common Ground/Surface Systems |

Processing, sharing, and fusing of airborne collections. |

After FY 2009 |

Naval Fires Network incompatibility. |

|

Joint Command and Control |

Command and control for all Services; Global Command and Control System (GCCS) successor. |

FY 2010 |

Schedule. Needed GCCS-Maritime upgrades. |

|

Integration |

|

||

|

Horizontal Fusion |

Demonstrations of information sharing and fusion. |

Variable |

Incorporating successes into Programs of Record. |

|

aExpected fielding time frame. |

|||

bandwidth and are subject to frequent communications outages caused by antenna blockages. Until the performance of NCES is known, and until it is clear to what degree the promise can be kept, one cannot be sure that NCES will support FORCEnet.

NCES efforts, in the main, have to do with network infrastructure. Issues of information flow, content, management, and representation do not currently have a strong GIG focus. These issues are represented in various forms and for different purposes by communities of interest (COIs), which are conceived (at least initially) as traditional groupings (e.g., processes) from non-network experiences. Developments within these COIs are highly driven by the culture of preexisting associations and are therefore likely to revert to traditional standards rather than to converge on common network paradigms (e.g., common ontologies) unless properly focused. No compliance criteria for COI participation have been developed. Issues of information integrity drive the concern in this area. Without a cohering function, the COIs will develop differing conventions (from data dictionaries to processing architectures), and the ability to maintain consistency when enterprise sharing is required will diminish.

Issues raised in Chapter 1 relating to information integrity across the network, information management, and system performance measures are not visibly addressed in the GIG. Some joint efforts may be addressing these issues, but the committee did not encounter them.

Combat systems require an extremely high degree of integrity, and FORCEnet includes combat systems. Chapter 5 discusses the issue of separating combat loops from the rest of FORCEnet so as to avoid the expense of combat-certifying the entire FORCEnet as spirals are developed.

Transition to IPv6 and to black core with IP encryptors cannot be accomplished overnight. DON will have to devise a plan with staged implementation and procedures to allow interoperation between converted and unconverted units.

3.7 COALITION OPERATIONS

All major U.S. operations and the majority of exercises in the Joint Exercise Program involve coalitions. These exercises provide the major venues for experiments, tests, and demonstrations for developing coalition capabilities and interoperability. U.S. naval forces also participate in demonstrations, exercises, and operations scheduled and run by allies and coalition partners. The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) has formal approaches for interoperability development, whereas the United States has vigorous but less-formal processes for developing interoperability with its other allies and security partners. The development of CENTRIX (Combined Enterprise Regional Information Exchange) and associated standard operating procedures for coalition planning and operations in the U.S. Central and Pacific Commands has been the foundation for recent coalition operations. At the level of operational planning and coalition (blue) force track-

ing, FORCEnet will extend into coalition operations. Some allies, such as Japan and Korea, with Aegis capabilities, are working toward interoperability in missile and air defense at the level of fire control.

The NATO Summit held in Prague in 2002 resulted in a major reorganization: there are now two major NATO commands—Allied Command Operations (ACO), headquartered in Europe, and Allied Command Transformation (ACT), headquartered in North America. NATO is fully embracing this transformation process, under the leadership of ACT. A critical element in that transformation is the generation of the NATO Network-Enabled Capability (NNEC). The NATO secretary general has stated that “Allied Command Transformation will shape the future of combined and joint operations and will identify new concepts and bring them to maturity, and then turn these transformational concepts into reality—a reality shared by the whole NATO alliance.”35 ACT will incorporate into the NATO inventory those concepts that address the needs of the future allied operating environment. NNEC will strive to integrate systems from across the alliance, resulting in an interoperable system of systems.

To achieve an operational system of systems, NATO requires a methodology for developing that architecture. The methodology is to enable the creation of multifunctional, multilayered communications and information systems that are consistent with the overarching NNEC concept. Furthermore, the methodology intends to ensure interoperability by formalizing requirements and specifying intersystem standards. Within NATO, the Research and Technology Organization (RTO) identifies, conducts, and promotes cooperative research and information exchange that meets the military needs of the alliance. In addition, RTO has the ability to draw upon resources across the alliance to carry out that task.

U.S. efforts to develop network-centric capabilities are leading allied and coalition efforts. Through routine interaction with allies and coalition partners, U.S. naval forces are well positioned to further FORCEnet implementation in this context.

3.8 CHALLENGES IN BRIDGING NETWORK-CENTRIC CONCEPTS AND JOINT CAPABILITIES

One of the most effective force transformations in recent history resulted from the Navy’s creating Submarine Development Group TWO in 1949, with the mission “to solve the problem of using submarines to detect and destroy enemy

|

35 |

Remarks by the Secretary General of NATO, Lord George Robertson, at the ceremony establishing the new NATO Transformation Command in Norfolk, Virginia, June 19, 2003. Available at www.defenselink.mil/news.Jun2003/N06192003_200306193.html. Accessed July 24, 2004. |

submarines.”36 In 1949, the U.S. submarine force had no capability to sink a submerged submarine. By 1969, as a result of Submarine Development Group TWO exercises, analyses, and continuous tactics and technology development, the U.S. submarine force had become the dominant antisubmarine capability in the world. This success derived from “a willingness to innovate, close and open ties to the technical community, unblinking candor in performance analysis, dedicated organic submarines focused on development, top-notch personnel, military and civilian, and a strong, clear mission focus.”37

The defense planning, joint capabilities integration and development, joint concept development and experimentation, JBMC2, joint testing, joint training, GIG development and acquisition processes, and coalition considerations described in this chapter are all separate activities with little interaction. Proposals to organize these activities around mission areas have proven difficult to implement for the large bureaucracies involved in each activity. Though efforts such as JBMC2 are striving to develop architectures around joint mission threads,38 the relationships between these architectures and network-centric enterprise architectures have yet to be illustrated. Absent an integrated program of concept development, experimentation, technology insertion, and system testing in joint and coalition exercises, it is highly uncertain that the challenges involved in transforming to network-centric enterprises and FORCEnet can be resolved, particularly at the tactical level where quality-of-service and latency issues are acute.

3.9 FINDINGS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

3.9.1 Findings

Following are the findings of the committee with respect to joint capability development and DOD network-centric plans and initiatives:

-

The leadership of the Navy and the Marine Corps is committed to the development of capabilities that will enable them to operate as components of a joint force with network-centric attributes. All recent combat operations have

|

36 |

“Submarine Warfare and Tactical Development: A Look—Past, Present and Future.” 1999. In Proceedings of the Submarine Development Group TWO and Submarine Development Squadron TWELVE 50th Anniversary Symposium, 1949–1999, held at U.S. Naval Submarine Base, Groton, Connecticut, May, p. 124. |

|

37 |

“Submarine Warfare and Tactical Development: A Look—Past, Present and Future.” 1999. In Proceedings of the Submarine Development Group TWO and Submarine Development Squadron TWELVE 50th Anniversary Symposium, 1949–1999, held at U.S. Naval Submarine Base, Groton, Connecticut, May, pp. 21–22. |

|

38 |

A description of mission threads is given in Chapter 4, Section 4.7.1. |

-

been joint, and the extent of joint interaction in military operations is only likely to increase. Thus, FORCEnet operational and materiel capabilities must be developed in a joint context.

-

The DOD requirements prioritization and acquisition, concept development and experimentation, testing, and training are in flux. Further refinements in these processes should be anticipated. It is critical that FORCEnet implementation couple into these larger DOD-wide processes. Aligning FORCEnet implementation with the guidance from the OSD regarding network-centric operations and warfare, increased support to combatant commanders, JBMC2, and the GIG will be challenging, but also could represent opportunities.

-

The new Joint Programming Guidance from the OSD will direct a greater portion of DON resources toward OSD and combatant commander priorities. If the new process works as intended and FORCEnet is perceived as providing joint capabilities responsive to combatant commander needs, FORCEnet is less likely to have to compete for funding within the available discretionary funds of the Navy and Marine Corps that will have been reduced as a result of mandated spending on joint capabilities. Whether the effect on FORCEnet is positive or not remains to be seen.

-

There is no set of future concepts for joint operations with adequate detail to inform and guide the Navy and Marine Corps in developing their concepts for participating in joint operations. Joint efforts to date based on the JCIDS have been largely concerned with very broad conceptual development. The Joint Staff has recently initiated work on a set of Joint Integrating Concepts that may provide the required specificity.

-

The JBMC2 roadmap treats FORCEnet as providing the single integrated maritime picture. The roadmap is meant to drive program priorities and schedules, presenting a potential challenge to FORCEnet spiral development. FORCEnet’s inclusion in the JBMC2 roadmap will create pressures for FORCEnet to synchronize development with other Service and joint efforts and programs, such as the Army’s Future Combat System (FCS), the Air Force Command and Control Constellation, and the joint DCGS and the related Joint Fires Network (JFN)/Tactical Electronic Surveillance developments.

-

Joint lessons learned from OIF and the major combat operations phase of OIF are affecting defense planning priorities. They emphasize joint action facilitated by shared awareness and interoperability. Ongoing operations in Iraq are pressing the OSD and the Services to adopt new approaches for rapidly fielding capabilities to address the challenges that deployed forces are facing, many of which involve networking and shared awareness. Since the lessons principally involve joint interoperability issues that affect ground operations, this effort may direct a significant portion of FORCEnet development toward providing remedies needed for Navy and Marine Corps ground operations.

-

The JFCOM joint experimentation process is beginning to transition from being based on JFCOM-originated concepts focused at the operational level

-

-

of war to becoming a broader process more widely serving the needs of the joint community and Services. Further progress in this direction is necessary, with particular attention on the tactical level of warfare, given the growing joint interaction at that level evident in recent conflicts. In participating in JFCOM experimentation activities, the Navy and Marine Corps need to keep their activities focused so that they do not become overwhelmed by the much greater JFCOM experimentation resources.

-

While JFCOM is the executive agent for joint experimentation, the regional combatant commands are becoming an increasing focus for joint concept development and experimentation. The fleet commands are a natural vehicle for interacting with the combatant commands in this regard, as has been the case such as in the interaction of the Pacific Fleet and its components with PACOM.

-

The OSD is trying to create the functionality of the Navy DEP in a JDEP. As JDEP develops, it has the potential to provide joint interoperability and integration infrastructure for FORCEnet in a manner similar to the way that the Navy DEP provides it for the fleet. The spiral development of FORCEnet will require capabilities similar to those developed for JDEP. The Navy is positioned to influence this development in ways that support Sea Trial and FORCEnet implementation. The Navy DEP and JDEP, currently focused on system interoperability, will need to evolve to support the network-centric aspects of the GIG.

-

The OSD-led training transformation involves significant investment that could be employed for FORCEnet development. FORCEnet implementation can leverage the DOD investment in training infrastructure in several ways, including distributed training and education of naval personnel as FORCEnet capabilities develop and through the development of FORCEnet capabilities in joint training exercises. The training transformation is meant to provide a common architecture for live, virtual, and constructive training and embedded training in major acquisitions programs that allows systems to link immediately into the global joint training infrastructure. Training with forces from other Services is expected to become routine as the training ranges become linked and deployment schedules are aligned. The joint assessment capability also provides a means for documenting capability enhancements provided by FORCEnet. Documented capability enhancements can help justify adaptive expenditures that support short spiral times.

-

Efforts by the ASD(NII) have created architectures, reference models, standards, and new paradigms (e.g., task, post, process, use (TPPU); and only handle information once (OHIO)) to drive enterprise network operations. The sufficiency or completeness of these directions is unknown.

-

Enterprise services have been described as a paradigm for network operations. No services-oriented architecture of this scale has been attempted.

-

The GIG is driven principally by technological considerations and network-centric theories and may not satisfy all warfighting needs.

-

-

FORCEnet implementation is finding the same challenges as those that the DOD faces in strengthening jointness and migrating to network-centric concepts and systems. This process involves many open questions that require careful design, experimentation, and growing experience to resolve. A successful FORCEnet implementation strategy has the potential to be a model for realizing network-centric capabilities across DOD.

3.9.2 Recommendations

Based on the findings presented above and on the issues described in this chapter, the committee recommends the following:

-

Recommendation for NETWARCOM, NWDC, and MCCDC: Continue to work with JFCOM to broaden its experimental perspective, with particular emphasis on joint operations at the tactical level. If necessary for these organizations to maintain focused commitment in the face of far larger JFCOM resources, the CFFC, and Commanding General, MCCDC, should provide guidance on the issues to be addressed and the partitioning of naval involvement in JFCOM, regional combatant commands, and Service concept development and experimentation activities.

-

Recommendation for the fleet commands and Marine Expeditionary Forces (MEFs): Build on current interactions with regional combatant commands in order to grow the relationship between naval and joint concept development and experimentation. This means ensuring both that naval concepts are properly embodied in joint concepts and that they reflect the needs of the joint concepts. Combatant command exercises should be used as a principal vehicle for exploring and refining the concepts. This responsibility could require that the fleets devote more resources to concept development.

-

Recommendation for NETWARCOM and MCCDC with technical support from such organizations as the Space and Naval Warfare Systems Command (SPAWAR) and the Office of Naval Research (ONR): Undertake a series of naval mission-based analyses to understand the technical limits to achieving network-centric operational concepts and identify approaches for dealing with potential operational degradations in network capabilities. Such analyses should indicate where reliance on more “traditional” capabilities (e.g., the use of localized versus distributed services) may still be necessary, and where increased attention to network path diversity and node heterogeneity is needed to reduce network vulnerability. These results should be shared with other Services and the joint community to increase the understanding of the limits on joint operations.39

-

Recommendation for the Deputy Chief of Naval Operations (DCNO) for Warfare Requirements and Programs (N6/N7) and the Deputy Commandant of the Marine Corps for Plans, Policies, and Operations (DCMC(PP&O)): Work to articulate clearly how FORCEnet capabilities pertain to joint operations and satisfy the needs of combatant commanders. In the context of the Joint Defense Capabilities Process and JCIDS, this line of argument will strengthen programs providing FORCEnet capabilities in the budget process. While assertions of the joint nature of FORCEnet capabilities have frequently been made by the Navy and Marine Corps in general terms, the committee has not seen any detailed analyses working through the arguments.

-

Recommendation for the fleet commands and MEFs: Work with the combatant commands to which they are assigned in order to understand and feed into the naval requirements process the capabilities needed by the combatant commands from naval forces. The CFFC, and Commanding General, MCCDC, would act as the intermediaries for feeding this information from the fleets and MEFs into the program planning processes of the Navy and Marine Corps.

-

Recommendation for the N6/N7 and the Marine Corps Director for Command, Control, Communication, Computers, and Intelligence (C4I): Adopt a prudent course with respect to joint GIG programs, endorsing the further development of these programs but also requiring a clear and continuing assessment of their technical and programmatic progress. In this context, the N6/N7 and the Director, C4I, should clearly understand the limits of applicability of network-centric capabilities, especially at the tactical level.

-

Recommendation for the N6/N7 and N8, and the Deputy Commandant of the Marine Corps for Programs and Resources (DCMC(P&R)): Articulate programmatic strategies, updated on an annual basis, for leveraging progress and accommodating developments in joint GIG programs. This strategy should lay out approaches for developing the necessary complementary naval capabilities (e.g., terminals, antennas) and describe technical and programmatic alternatives corresponding to the status of joint programs—that is, whether they have remained on schedule, slipped, or failed to meet their objectives. The strategy should also indicate how to leverage joint GIG capabilities as they become available. While some such capabilities will not be deployable for many years (e.g., the TSAT), others will be available in the near term (e.g., initial releases of NCES, Horizontal Fusion services).

-

Recommendation for the Assistant Secretary of the Navy for Research, Development, and Acquisition (ASN(RDA)) with support from the program executive officer (PEO) C4I & Space, the PEO Space Systems, SPAWAR, and the Marine Corps Systems Command (MARCORSYSCOM): Track and provide input to the technical development of joint GIG programs to ensure that as these programs evolve, they continue to satisfy naval needs. This objective is best accomplished through naval participation in the programs. The ASN(RDA) should build on current naval participation to ensure that the involvement re-

-

mains substantive and is across all major GIG programs. The ASN(RDA) should also see that the proper operational perspective (e.g., through the involvement of NETWARCOM) is brought to bear in this activity.

-

Recommendation for the N6/N7, the ASN(RDA), and the MARCORSYSCOM: Fully impose the network-centric criteria mandated by the ASD(NII), in the development and execution of naval programs, subject to any necessary refinement of these criteria. Since the criteria are in their initial use now, the N6/ N7, the ASN(RDA), and MARCORSYSCOM should work with the ASD(NII) to refine these criteria as necessary, prior to their full imposition. The use of these criteria will further strengthen related internal policies of the Navy and Marine Corps. Furthermore, if the ASD(NII) network-centric reviews gain strong influence in the DOD budget process, meeting the criteria will be necessary to ensure adequate funding of programs.

-

Recommendation for the N6/N7 and the ASN(RDA):40 Work with the OSD and the other Services to develop a better understanding of, and eventually to develop guidelines and principles for, how the numerous architectures being developed in DOD can be effectively integrated. Particular attention is necessary at the tactical level of warfare, since architectural development for the GIG has not explored that level to a significant extent. The N6/N7 and the ASN(RDA) would be supported by SPAWAR, NETWARCOM, and the MARCORSYSCOM in this work. Interaction with the combatant commands (particularly the JFCOM and STRATCOM) and combat support agencies (particularly the Defense Information Systems Agency (DISA)) would also be required.

-

Recommendation for the ASN(RDA) and the CFFC: Coordinate with the Director of Operational Test and Evaluation and the DISA to leverage the DOD investment in the JDEP while expanding the Navy DEP to accommodate the spiral development of FORCEnet capabilities.

-

Recommendation for the ASN(RDA) and the DCNO for Fleet Readiness and Logistics (N4): Coordinate with the Under Secretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness to exploit DOD investments in Training Transformation to support FORCEnet development. The committee recommends that CFFC and Sea Trial operational agents schedule fleet battle experiments in exercises employing the joint national training capability.

-

Recommendation for CFFC and NETWARCOM: Interface with NATO ACT and the NATO RTO to foster interoperable coevolution of the capabilities of FORCEnet and NATO Network Enabled Systems. Commanders of the Pacific Fleet and Fifth Fleet, as naval component commanders respectively in PACOM and U.S. Central Command, should coordinate the specific requirements for the coevolution of FORCEnet capabilities in their theaters.