6

Employment, Insurance, and Economic Issues

A history of cancer can have a significant impact on employment opportunities and may also affect the ability to obtain and retain health and life insurance. In addition, financial difficulties may arise because cancer survivors’ health-related work limitations may necessitate a reduced work schedule. The economic burden of cancer can be compounded by high out-of-pocket expenses for prescription drugs, medical devices and supplies, and expenses related to co-insurance and copayments. These employment, insurance, and economic issues are not necessarily limited to the cancer survivor—they may extend to family members, limiting access to insurance and posing a financial burden. The extent of these socioeconomic problems and current legal remedies to address them are described in this chapter, as are potential programmatic, educational, legislative, and advocacy responses.1 Selected federal and state programs are described that are relevant to cancer survivors, including the Medicare prescription drug program that will be implemented in 2006; a state Medicaid option available since 2000 to provide poor and uninsured women with coverage for treatment and follow-up of breast and cervical cancer; recent federal investments in state high-risk insurance pools that provide insurance coverage to people who cannot get insurance because of poor health; and federal income replacement programs through the Social Security Administration for individuals too disabled to work.

EMPLOYMENT

Impact of Cancer on Survivors’ Employment Opportunities

There are an estimated 3.8 million working-age adults (ages 20 to 64) with a history of cancer as of 2002, and consequently more cancer survivors are in the workplace now than ever before, (NCI, 2005). The proportion of individuals with a history of cancer rises with age, from 1 percent among individuals ages 40 to 44 to 8 percent among those age 60 to 64 (see Chapter 2). Consequently, many employers have had to address issues related to the reintegration of workers following their treatment and the alteration of work schedules and environment to accommodate any lingering cancer-related impairments.

Most cancer survivors who worked before their diagnosis return to work following their treatment (Spelten et al., 2002). In fact, with the advent of effective interventions to curb the side effects of cancer therapies and an increased reliance on outpatient care, some individuals are able to work throughout their cancer treatment (Messner and Patterson, 2001). Retaining one’s employment status has obvious financial benefits and is often also necessary for health insurance coverage, self-esteem, and social support (Voelker, 1999; Spelten et al., 2002). On the other hand, cancer may prompt retirement from an undesirable job or launch a search for a new career that is more satisfying personally, but less lucrative. Work after cancer must therefore be assessed in the context of an individual’s priorities and values, rather than exclusively using social or economic metrics (Steiner et al., 2004).

Employers, supervisors, and co-workers may assume that persons with cancer are not able to perform job responsibilities as well as they did before the diagnosis. They may also perceive them as a poor risk for promotion. These misconceptions can lead to subtle or blatant discrimination in the workplace (Messner and Patterson, 2001). Cancer survivors have reported problems in the workplace that include dismissal, failure to hire, demotion, denial of promotion, undesirable transfer, denial of benefits, and hostility (NCCS and Amgen, undated; Fesko, 2001; Hoffman, 2004b). Studies conducted prior to the passage of comprehensive employment discrimination laws suggest that survivors of cancer encountered substantial employment obstacles (Mellette, 1985; Hoffman, 1989, 1991; Bordieri et al., 1990; Brown and Ming, 1992).

Federal and state laws passed in the early 1990s have helped to ease problems related to job discrimination. The most important is the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), which protects disabled workers. In addition, the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) and the Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act (COBRA) have

helped workers move from one job to another without loss of health insurance. Since the enactment of these laws (and their enforcement), employment practices have improved and employees have gained some protections (Hoffman, 1999). Common accommodations made for those living with illnesses include reduced and flexible schedules. Such flexibility is increasingly common in the workplace to meet the needs of employees with family responsibilities. However, providing flexibility in production or assembly line scheduling can be more difficult for “blue collar” workers (Voelker, 1999). Even with these new protections and improvements in employer practice, contemporary workers may lose employment because of cancer (Box 6-1).

To fully understand the impact of cancer on work outcomes, one would

|

BOX 6-1 Allison Yowell, a seventh-grade teacher in a Virginia public school, was forced from her job when her Hodgkin’s disease recurred. Although her prognosis was good, school officials notified her that she must resign, or face firing, because she had used all her sick days. As a recent hire, she was ineligible to request leave without pay. It was recommended that she resign before being terminated to avoid marring her teaching record. She submitted her resignation, but was reinstated only after adverse publicity regarding the case. Ms. Yowell, who wanted 4 months of leave without pay, couldn’t take advantage of the federal Family and Medical Leave Act, which grants 12 unpaid weeks per year, because it applies only after an employee has worked a full year. John Magenheimer, who had headed a research laboratory at a major company, was recovering from surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation treatment for cancer when he learned that his company had fired him and that his health, life, and dental insurance had been terminated. He and 180 other employees of the company who had been placed on long-term disability were fired. Most companies used to pay health benefits for the long-term disabled until they were 65, but as health insurance costs and the number of disabled employees have climbed, more companies are firing them. According to a survey of 723 companies in 2002, 27 percent had a policy to dismiss employees as soon as they went onto long-term disability and 24 percent dismissed them at a set time thereafter, usually 6 to 12 months. Only 15 percent of companies had a policy to keep the disabled on as employees with benefits until age 65. Mr. Magenheimer had the option of continuing his health insurance through a federal law known as COBRA, and as a disabled worker he could purchase Medicare coverage after 18 months. Both kinds of coverage cost thousands of dollars a year, which many disabled workers can ill afford. SOURCES: Pereira (2003); Laris (2005a,b). |

ideally have results from studies that had the following six characteristics (Steiner et al., 2004):

-

Inclusion of cancer survivors that represented the entire population of U.S. cancer survivors. Many studies are based on survivors followed at one cancer center, or who are from particular geographic areas. Their employment experience may not reflect that of the nation. Ideally, survivors would be selected for study from population-based cancer registries.

-

Designed to provide a prospective and longitudinal look at work outcomes so that both short-term and long-term work outcomes could be assessed and the dynamic nature of employment could be understood.

-

Include assessments of work, including information on the type, amount, content, physical demands, cognitive demands, and attitudes about work.

-

Include assessments of the impact of cancer on the economic status of the individual and the family.

-

Identify moderators of work return and work function, particularly those that are susceptible to intervention (e.g., availability of health insurance and disability benefits to offset lost income).

-

Include a cohort of survivors that is sufficiently large to allow multivariate statistical analysis and that provides information on important groups (e.g., minority groups, cancer types).

The committee reviewed the literature published in the past 10 years on the employment experience of U.S. cancer survivors who were studied in 1992, the year the ADA took effect, or later.2 Most of the studies reviewed had some, but rarely all, of the ideal attributes just described. There are few prospective studies of cancer’s effects on employment, but those that are available provide important insights into how interventions could be designed to assist cancer survivors.

In one prospective study, women with invasive breast cancer were less likely to work 6 months following diagnosis relative to a control sample of women. Breast cancer survivors who remained working worked fewer hours than women in the control group (Bradley et al., 2005a). At 12 months, however, many women who had stopped working had returned to work (Bradley, 2004). The nonemployment effect of breast cancer diagnosis and treatment at 6 months was twice as large for African-American women. Similar findings were evident among men with prostate cancer. Here, 28

percent of men were not employed 6 months following diagnosis but, at 12 and 18 months, survivors’ employment was statistically not different from controls (Bradley, 2004). At 12 months, 26 percent of men with prostate cancer reported that cancer interfered with their ability to perform tasks that involved physical effort (Bradley et al., 2005b). Up to 16 percent of men said that they noticed changes in their ability to perform cognitive tasks (e.g., concentrate, keep up with others, learn new things). The implication of these findings is that interventions to assist survivors who stop working (e.g., income replacement programs, information about access to health insurance) are needed within 6 months of diagnosis. Workplace reintegration programs may be most needed through the year following diagnosis.

Nearly one out of five cancer survivors reported cancer-related limitations in ability to work when interviewed 1 to 5 years following their diagnosis as part of one of the largest cross-sectional studies to date (Short et al., 2005b). Nine percent were unable to work at all. Labor force participation dropped by 12 percentage points from diagnosis to follow-up and about two-thirds of survivors who quit working attributed the change to cancer. Other studies have found the drop in employment following cancer to be similar in magnitude. For example, a 10 percentage point greater decline in employment was noted among breast cancer survivors as compared to women without breast cancer (Bradley et al., 2002a,b).

The impact of cancer on employment has not been well studied across all types of cancer. However, work-related outcomes have been shown to be significantly worse for cancers of the central nervous system, hematologic cancers (Short et al., 2005b), and cancer of the head and neck. In one study, 52 percent of survivors of head and neck cancer who had worked before their diagnosis were disabled by their cancer treatment and could no longer work when assessed, on average, more than 4 to 5 years following their diagnosis (Taylor et al., 2004). Nearly three-quarters (74 percent) of survivors considered potentially cured of acute myelogenous leukemia (excluding those receiving allogenic marrow transplants) returned to full-time work according to a long-term follow-up study (median of 9.2 years from first or second complete remission) (de Lima et al., 1997). Less than a third of those who were not working cited physical limitation as the reason.

Other studies of cancer survivors have also shown that most cancer survivors continue to work, but that a minority have limitations that interfere with work. Of those working at the time of their initial diagnosis, 67 percent of survivors of lung, colorectal, breast, or prostate cancer were employed 5 to 7 years later when interviewed in 1999 (Bradley and Bednarek, 2002). Survivors in this study who stopped working did so because they retired (54 percent), were in poor health or disabled (24 percent), quit (4 percent), their business closed (9 percent), or for other reasons

TABLE 6-1 Limitations Imposed by Cancer and Its Treatment on Patients Currently Working

|

At least some of the time task requires: |

Cancer Interfered with Work Performance (percentage) |

|

Physical tasks |

18 |

|

Lift heavy loads |

26 |

|

Stoop, kneel, or crouch |

14 |

|

Concentrate for long periods of time |

12 |

|

Analyze data |

11 |

|

Keep pace with others |

22 |

|

Learn new things |

14 |

|

SOURCE: Adapted from Bradley and Bednarek (2002). |

|

(9 percent). Many employed survivors worked in excess of 40 hours per week, although some reported various degrees of disability that interfered with job performance. When work required lifting heavy loads, for example, 26 percent of subjects reported that cancer interfered with their performance (Table 6-1).

Other investigators point to the vulnerability of employees with jobs involving manual labor. In one study, type of occupation was the main determinant of whether individuals were employed after diagnosis. Although 76 percent of respondents indicated that they were working at the time of diagnosis and 82 percent said they wanted to work full- or part-time, only 56 percent were working at the time of the study (Rothstein et al., 1995). Laborers were most likely, and professionals least likely, to have some of their job duties reassigned upon their return to work.

Relatively few studies have examined the effect of cancer on income in the context of the family household. In one study that studied such effects, breast cancer survivors who were working at the time of their diagnosis experienced higher rates of functional impairment and significantly larger reductions in annual earnings over the 5-year study period than did working control subjects. These losses arose mostly from reduced work effort, not changes in pay rates. Changes in total household earnings were lower for survivors, suggesting the presence of family adjustments to the disease. However, no significant differences were detected between the groups in changes in total income or assets over the study period (Chirikos, 2001; Chirikos et al., 2002a,b). This study suggests that cancer can have an economic impact on the entire family, requiring compensatory employment behaviors on the part of family members to maintain earnings.

Analyses of national health surveys have provided some information on

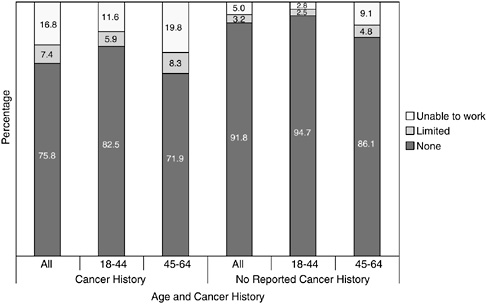

the effects of cancer on employment. According to analyses of the 2000 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), cancer survivors were found to have poorer outcomes across all employment-related burden measures relative to matched control subjects (Yabroff et al., 2004). Cancer survivors were less likely than control subjects to have had a job in the past month. Furthermore, they were more likely to be unable to work because of health, more limited in the amount or kind of work because of a health problem, and had more days lost from work in the past year. The decrements in productivity were generally consistent across tumor sites. When analyzed by time since diagnosis, a higher percentage of survivors diagnosed in the past year also reported having jobs than survivors in any of the other time-since-diagnosis intervals. However, this group of survivors also had the most reported work loss days. This analysis included information on cancer survivors of all ages.3 In an analysis of three years of NHIS data (1998 to 2000) limited to adults ages 18 to 64, nearly one in six individuals (17 percent) with a history of cancer reported that they were unable to work because of a physical, mental, or emotional problem (Hewitt et al., 2003). An additional 7.4 percent of cancer survivors were limited in the kind or amount of work they could do. This level of work limitation exceeded that of working-age individuals without a history of cancer (Figure 6-1). In an attempt to isolate cancer-related effects, investigators compared individuals reporting a history of cancer but no other chronic disease to individuals without a history of cancer or with no other chronic illness. Using multivariate analyses to control for potentially confounding factors (i.e., age, sex, race/ethnicity, educational attainment, health insurance status, and marital status), individuals with cancer but no other chronic disease were found to be three times more likely to be unable to work than individuals without a history of cancer and reporting no chronic illness. The likelihood of work limitation was much higher among cancer survivors who also reported comorbid chronic diseases (i.e., cardiovascular disease, diabetes, emphysema, ulcer, weak/failing kidneys, liver condition). They were 12 times more likely to be unable to work relative to those without cancer or other chronic illnesses.

The NHIS in 1992 included a supplement funded by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) with a section on issues related to cancer survivorship. Individuals who reported a recent history of cancer (within the past 10 years) were asked about changes in health or life insurance coverage and cancer-related problems with employment. Nearly one in five (18.2 percent) individuals who worked immediately before or after their cancer was

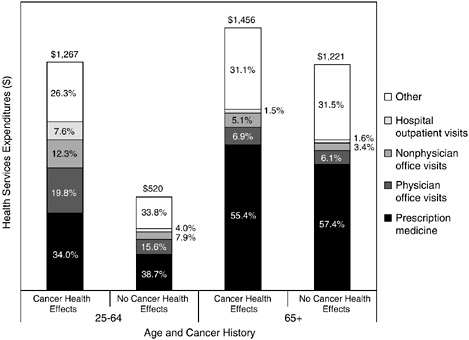

FIGURE 6-1 Work limitations by age and self-reported history of cancer, 1998–2000.

SOURCE: Hewitt et al. (2003).

diagnosed (but who were not self-employed) reported at least one of the following problems (Hewitt et al., 1999):

-

Believed they could not take a new job because of a change in insurance related to cancer (13.2 percent).

-

Believed they could not change jobs because of cancer (7.8 percent).

-

Faced on-the-job problems from an employer or supervisor directly related to their cancer (4.5 percent).

-

Refrained from applying for a new job because they did not want their medical records made public (4.4 percent).

-

Were fired or laid off from their job because of their cancer (3.7 percent).

Kessler and colleagues, in an analysis of the MacArthur Foundation Midlife Development in the United States (MIDUS) survey, found 88 percent of employed people who develop cancer remain at work after receiving their diagnosis and during at least some part of their treatment (2001). Of all of the conditions examined, cancer had the highest reported prevalence of any 30-day work impairment. Two-thirds (66 percent) of those reporting

cancer reported such impairment as compared to 48 percent of those with heart disease and 39 percent of those with arthritis.4 An analysis of symptoms reported on the survey suggested that fatigue may have accounted for much of the impact of cancer on work impairment.

Whether or not cancer survivors disclose their diagnosis once they return to work has not been well researched. In one study of colorectal cancer patients who had been employed before their diagnosis, most (89 percent) returned to work and, of those returning to work, most disclosed their cancer history to employers (81 percent) and co-workers (85 percent) and did so for personal and work-related reasons (Sanchez and Richardson, 2004). Communication with physicians about work return decisions may have facilitated cancer history disclosure. Such high disclosure rates could be accounted for by the fact that anyone who requests a formal leave of absence from work must disclose their cancer diagnosis. Discussions with physicians about work return decisions should take place prior to the initiation of treatment because the acute effects of treatment may affect one’s ability to work full time. Some patient’s treatment decisions may be influenced by employment considerations.

From an employer’s perspective, cancer represents a potential health and productivity burden. In addition to medical costs that may be borne by employers, there are concerns about absenteeism from work, disability program use, workers’ compensation program costs, turnover, family medical leave, and on-the-job productivity losses. Consequently, the cost of cancer to employers greatly exceeds the cost of health insurance alone (Lee, 2004). Cancer accounts for about 10 percent of an employer’s or insurer’s annual medical claim costs, 10 percent of short-term disability claim costs, and 10 percent of long-term disability costs, according to a recent analysis (Pyenson and Zenner, 2002). One study that examined physical and mental health conditions contributing to employer health and productivity cost burden found that cancer ranked relatively low in burden relative to other chronic conditions such as heart conditions, diabetes mellitus, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, low back disorders, trauma, sinusitis, and renal failure (Goetzel et al., 2003).5 Other investigators found annual health care and disability costs for persons with cancer to be about five times

higher than for their counterparts without cancer (Barnett et al., 2000).6 Medical conditions not directly related to cancer accounted for about half of the total excess expenditures for patients with cancer. For example, infections, asthma, and dental procedures, although not immediately thought of as being associated with cancer, cost considerably more among cancer patients than controls.

In summary, a number of studies have been conducted to gauge the effect of cancer on employment. However, it is difficult to judge overall effects because these studies have:

-

Included individuals with different types of cancer and survival probabilities;

-

Assessed employment patterns at different lengths of time following treatment;

-

Had relatively low participation rates, with healthier individuals enrolling in studies more readily than less healthy individuals;

-

Examined employment at one point in time, possibly obscuring important transitions in and out of work over time;

-

Been conducted in different parts of the country with varying employment patterns; and

-

Had no control group or used control groups that may not have been well matched to subjects. Without adequate control subjects in such studies, it is difficult to distinguish declines in employment following cancer from those that might be expected for other reasons.

Information from the one prospective study that has been conducted indicates that employment is most affected in the period immediately following treatment, suggesting that programs, policies, and financial assistance are critical at this time. The type of occupation appears to be a key determinant of employment difficulties, with workers whose jobs involve physical labor most adversely affected. In terms of cancer site, cancers of the central nervous system, hematologic cancers, and head and neck cancer seem to be associated with poorer work outcomes. The finding from one of the largest cohort studies, that roughly 20 percent of people working at the time of their diagnosis face cancer-related work limitations 2 to 3 years later, is consistent with results of cross-sectional national survey research. This research suggests that cancer is one of several chronic conditions that markedly increase the likelihood of work-related disability.

Despite laws allowing portability of health insurance (see section on health insurance below), individuals with a history of cancer report in recent studies of being afraid to change jobs because of concerns about continuation of health insurance. More than 25 percent of cancer survivors in Short and colleagues’ recent study expressed such fears (Short et al., 2005a). Most individuals returning to work appear to inform their supervisors and colleagues of their cancer for both personal and work-related reasons. Relatively few (5 percent) cancer survivors faced on-the-job problems from an employer or supervisor directly related to their cancer, according to survey research conducted in the early 1990s. However, at this time, 4 percent of cancer survivors employed before their diagnosis said they were fired or laid off from their jobs because of their cancer.

Population-based, prospective cohort studies with adequate control groups are needed to better understand the effects of cancer on employment and in order to observe transitions in and out of the work force over time following diagnosis. Also needed are studies of work-related outcomes other than employment status alone (e.g., full-time versus part-time, job mobility, limitations in ability to work) and systematic assessments of employment differences among cancer survivors, as well as between cancer survivors and noncancer control groups. Efforts to identify remediable risk factors and interventions to ameliorate the deleterious effects of cancer on employment are also needed. Investigators have proposed a conceptual model of work after cancer and have defined important work outcomes that should be monitored to improve our understanding of the relationships among cancer, quality of life, and work outcomes (Steiner et al., 2004).

Cancer Survivors’ Current Employment Rights

Although cancer survivors do not have an unqualified right to obtain and retain employment, they do have the right to freedom from discrimination and to be treated according to their individual abilities. Four federal laws—the ADA, the Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA), the Employee Retirement and Income Security Act (ERISA), and the Federal Rehabilitation Act—provide cancer survivors with some protection against employment discrimination.

Americans with Disabilities Act

The Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 prohibits certain employers from discriminating against individuals with disabilities (see Box 6-2). A qualified individual with a disability is protected by the ADA if he or she can perform the essential functions of the job. Under the ADA, a disability is a major health impairment that substantially limits the ability to do

|

BOX 6-2 What is the ADA? Title I of the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 prohibits private employers, state and local governments, employment agencies, and labor unions from discriminating against qualified individuals with disabilities in job application procedures, hiring, firing, advancement, compensation, job training, and other terms, conditions, and privileges of employment. Who does the ADA cover? The ADA covers employers with 15 or more employees, including state and local governments. It also applies to employment agencies and to labor organizations. The ADA’s nondiscrimination standards also apply to federal-sector employees. Who is considered disabled under the ADA? An individual with a disability is a person who has a physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more major life activities; has a record of such an impairment; or is regarded as having such an impairment. A qualified employee or applicant with a disability is an individual who, with or without reasonable accommodation, can perform the essential functions of the job in question. Reasonable accommodation may include, but is not limited to:

What is an employer required to do under the ADA? An employer is required to make a reasonable accommodation to the known disability of a qualified applicant or employee if it would not impose an “undue hardship” on the operation of the employer’s business. Undue hardship is defined as an action requiring significant difficulty or expense when considered in light of factors such as an employer’s size, financial resources, and the nature and structure of its operation. An employer is not required to lower quality or production standards to make an accommodation, nor is an employer obligated to provide personal-use items such as glasses or hearing aids. SOURCE: EEOC (2004b). |

everyday activities, such as talking, caring for oneself, and getting to work. Some have the misperception that “hidden” disabilities such as cancer, AIDS, arthritis, and mental illness are not bona fide disabilities needing accommodation. The U.S. Department of Labor, however, explicitly states that such hidden disabilities, just like those that are visible, can result in functional limitations that substantially limit one or more of the major life activities (U.S. Department of Labor, 2000).

Cancer survivors, regardless of whether they are in treatment, in remission, or cured, are usually protected as persons with a disability because their cancer represents an impairment that substantially limits a major life activity. Federal courts and the Equal Employment Opportunities Commission (EEOC) usually consider cancer to be a disability under the ADA (Hoffman, 1999). Whether a cancer survivor is covered by the ADA is determined, however, on a case-by-case basis. Because the U.S. Supreme Court has not, to date, squarely addressed whether all cancer survivors are protected by the ADA, cancer survivors’ rights under the law vary depending on the facts of the individual case and the court in which the case is heard.

Some courts have concluded that cancer survivors are “persons with a disability” as defined by the statute. Other courts, however, have placed cancer survivors in a “Catch-22” by concluding that a cancer survivor who is sufficiently healthy to work is not a person with a disability as defined by the ADA (Hoffman, 2000). In one case a woman with breast cancer was acknowledged to have experienced nausea, fatigue, swelling, inflammation, and pain resulting from her treatment, but the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit found that she could nonetheless perform her essential job duties with accommodations (Ellison v. Software Spectrum Inc.). Although the Court of Appeals found that the woman’s cancer affected her ability to work, it concluded that these limitations were not sufficient to render her a “person with a disability” as defined by the ADA. Other courts have followed the reasoning of the Fifth Circuit and rejected lawsuits by cancer survivors. In another case, a long-term survivor of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, fired because his employer feared that future health insurance claims would cause his insurance costs to rise, was determined not to be covered under the ADA after his dismissal (Hirsch v. National Mall and Serv., Inc.). The court concluded that “the ADA was not truly meant to apply to this situation” because the claimant was discriminated against due to the costs of his cancer treatment, and not because of the cancer itself” (Hirsch, 989 F. Supp. 977, 980 [N.D. Ill. 1997]).

The ADA prohibits discrimination in most job-related activities such as hiring, firing, and the provision of benefits. In most cases, a prospective employer may not ask applicants if they have ever had cancer. An employer has the right to know only if an applicant is able to perform the essential

|

BOX 6-3

SOURCE: Job Accommodation Network (Loy and Batiste, 2004). |

functions of the job. A job offer may be contingent on passing a relevant medical exam, provided that all prospective employees are subject to the same exam. An employer may ask detailed questions about health only after making a job offer.

Cancer survivors who need extra time or help to work are entitled to a “reasonable accommodation.” Common accommodations for cancer survivors include changes in work hours or duties to accommodate medical appointments and treatment side effects (Box 6-3). An employer does not have to make changes that would impose an “undue hardship” on the business or other workers. “Undue hardship” refers to any accommodation that would be unduly costly, extensive, substantial, or disruptive, or that would fundamentally alter the nature or operation of the business. For example, an employer may replace a survivor who has to miss an extended period of work (e.g., 6 months or longer) that cannot be performed by a temporary employee.

Some employers express concerns about the costs of accommodations and whether accommodations interfere with typical work schedules and

productivity (Roessler and Sumner, 1997). According to some estimates, the costs of accommodations for workers with disabilities needing special accommodations are typically very low; 71 percent of accommodations cost $500 or less, with 20 percent of those costing nothing (U.S. Department of Labor, 2004b).

Most employment discrimination laws protect only the employee. The ADA offers protection more responsive to survivors’ needs because it also prohibits discrimination against family members. Employers may not discriminate against workers because of their relationship or association with a “disabled” person. Employers may not assume that an employee’s job performance would be affected by the need to care for a family member who has cancer. An important exclusion of the Americans with Disabilities Act is contractual employees. Many people are “self-employed,” but contract their services to large organizations that may terminate a survivor’s contract without regard to the provisions of the ADA. Also excluded from ADA protection are those working for employers with fewer than 15 employees. Among private employees, an estimated 15 percent work for companies with fewer than 10 employees and an additional 11 percent work for companies with 10 to 19 employees (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2005).7

The EEOC is charged with enforcing the ADA and other civil rights laws. During the 4-year period FY 2000–2003, the EEOC received 1,785 charges of cancer-related disability discrimination under the ADA, representing about 3 percent of all charges during this period (Table 6-2). The EEOC resolved 2,013 cancer-related disability discrimination charges,8 with one-quarter (510/2,013) having outcomes favorable to charging parties or charges with meritorious allegations. The EEOC recovered $11 million in monetary benefits for 352 people (including charging parties and other aggrieved individuals). This amount does not include monetary benefits obtained through litigation.

Another source of information regarding the extent of cancer-related employment problems is the Job Accommodation Network (JAN), a service of the Office of Disability Employment Policy of the U.S. Department of Labor (U.S. Department of Labor, 2004c). JAN provides employers and other interested parties with information on job accommodations and employment opportunities and policies. In 2003, JAN handled 514 cases related to cancer (about 2 percent of their calls and e-mails). These came from

TABLE 6-2 Resolution of Cancer-Related ADA Charges, FY 2000–2003

|

Number of charges for all disabilities/conditions |

63,675 |

|

Cancer-related charges |

1,785 |

|

Cancer-related resolutions |

2,013 |

|

Merit resolutionsa |

510 |

|

People with monetary benefits |

352 |

|

Total monetary benefit |

$10,969,314 |

|

aMerit resolutions are charges with outcomes favorable to charging parties and/or charges with meritorious allegations. These include negotiated settlements, withdrawals with benefits, successful conciliations, and unsuccessful conciliations. SOURCE: U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC, 2004a). |

|

both employers and individuals. Most inquiries related to accommodations such as use of leave time and scheduling issues (Personal communication, A. Hirsh, JAN, June 14, 2004).

Family and Medical Leave Act

The Family and Medical Leave Act enacted in 1993 requires employers with at least 50 workers to provide certain benefits for serious medical illness, including cancer, for employees or dependents (U.S. Department of Labor, 2004a). The employee must have worked with his or her employer for at least 1 year. Box 6-4 shows a number of benefits of the statute.

The FMLA attempts to balance the needs of the employer and employee. It:

-

Requires employees to make reasonable efforts to schedule foreseeable medical care so as to not unduly disrupt the workplace;

-

Requires employees to give employers 30 days’ notice of foreseeable medical leave, or as much notice as is practicable;

-

Allows employers to require employees to provide certification of medical needs and allows employers to seek a second opinion, at the employer’s expense, to corroborate medical need; and

-

Permits employers to provide leave provisions more generous than those required by the FMLA.

|

BOX 6-4

SOURCE: U.S. Department of Labor (2004a). |

The Employee Retirement and Income Security Act

The Employee Retirement and Income Security Act (ERISA) prohibits an employer from discriminating against an employee to prevent him or her from collecting benefits under an employee benefit plan. Employee benefit plans are defined broadly, and include any plan providing “medical, surgical, or hospital care benefits, or benefits in the event of sickness, accident, disability, death, or unemployment.” Employers who offer group benefit packages to their employees are subject to ERISA. Some employers fear that the participation of a cancer survivor in a group medical plan will drain benefit funds or increase the employer’s insurance premiums. An employer may violate ERISA if, upon learning of a worker’s cancer history, it dismisses that worker to exclude him or her from a group health plan. An employer also may violate ERISA by encouraging a person with a cancer history to retire as a “disabled” employee. Most benefit plans define disability narrowly to include only the most debilitating conditions. Individuals with a cancer history often do not fit under such a definition and should not be compelled to so label themselves.

ERISA covers both participants (employees) and beneficiaries (spouses and children). Thus, if the employee is fired because his or her spouse has cancer, the employee may be entitled to file a claim. ERISA, however, is

inapplicable to many victims of employment discrimination, including individuals who are denied a new job because of their medical status, employees who are subjected to differential treatment that does not affect their benefits, and employees whose compensation does not include benefits.

Federal Rehabilitation Act

The Federal Rehabilitation Act of 1973 is designed to promote equal employment opportunities for people with disabilities. Unlike the ADA, it is limited to employers of any size that receive money, equipment, or contracts from the federal government. Types of employers subject to the Act include schools, hospitals, defense contractors, and state and local governments. The Act does not apply to the military. The Federal Rehabilitation Act uses the same definition of “individual with a disability” as does the ADA. Also like the ADA, it requires employers to make reasonable accommodations to the physical or mental limitations of qualified individuals.

Executive Order

Unlike many private and state employees, federal employees are protected from genetic-based discrimination. An Executive Order issued in 2000 prohibits federal departments and agencies from making employment decisions about civilian federal employees based on protected genetic information (White House, 2000). The Order also prohibits federal employers from requiring genetic tests as a condition of being hired or receiving benefits.

Genetic nondiscrimination laws have also been enacted in most states. Discrimination in hiring, firing, or terms of employment based on the results of genetic tests is prohibited in 33 states, with many states also restricting the access of employers to genetic information (NCSL, 2005). Some states extend the protections to inherited characteristics, family history, the test results of family members, and information on receipt of genetic services.

State Employment Rights Laws

All states except Alabama and Mississippi have laws that prohibit discrimination against people with disabilities in public and private employment (Hoffman, 2002, 2004b).9 Several states, such as New Jersey, cover

|

BOX 6-5 In Washington state, the “Sick Leave for Sick Families” bill was signed into law in 2002. The bill allows workers, public and private, to use sick leave and other paid leave to care for a child with a medical condition requiring treatment or supervision, or to care for a spouse, parent, parent-in-law, or grandparent who has a serious health condition or an emergency condition. Other states, such as Arizona and Hawaii, have also proposed this type of initiative. In other states, such as California, New Jersey, and New York, lawmakers have introduced plans to extend temporary disability insurance benefits to workers who take family and medical leave. California signed S.B. 1661 into law in 2002, expanding the state’s disability insurance program to provide up to 6 weeks of wage replacement benefits to workers who take time off to care for a seriously ill child, spouse, parent, or domestic partner, or to bond with a new child. Another model under consideration in Illinois creates a cost-sharing fund, with contributions from the employer, employee, and state, and provides employees on leave with partial wage replacement. In Hawaii, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Washington, states have proposed establishing temporary disability Family Leave Insurance funds, financed by small payroll contributions by employers and/or employees, which would help working families SOURCE: Center on an Aging Society (2004). |

all employers regardless of the number of employees. The laws in most states, however, cover only employers with a minimum number of employees. A few states, such as California and Vermont, expressly prohibit discrimination against cancer survivors.

Most state laws define “individual with a disability” much as it is defined in the ADA. Therefore, most survivors in those states would be considered “disabled” under those state discrimination laws. The rights of cancer survivors in states whose laws do not mirror the ADA vary depending on how those laws define the protected class.

Many states have leave laws similar to the federal FMLA in that they guarantee employees in the private sector unpaid leave for pregnancy, child-birth, and the adoption of a child (see Box 6-5). Some state laws provide employees with medical leave to address a serious illness, such as cancer. Several states provide coverage more extensive than the federal law.

State medical leave laws vary widely as to:

-

How long an employee can take leave;

-

Which employees may take leave (most states require an employee to have worked for a minimum period of time);

-

Which employers must provide leave (a few states have leave laws that apply to employers of fewer than 50 employees);

-

The definition of “family member” for whose illness an employee may take family medical leave;

-

The type of illness that entitles an employee to medical leave;

-

How much notice an employee must give prior to taking leave;

-

Whether an employee continues to receive benefits while on leave and who pays for them;

-

How the law is enforced (by state agency or through private lawsuit); and

-

Provision and extent of replacement wages.

Programs to Ameliorate Employment Problems

Most employers treat cancer survivors fairly and legally. Some employers, however, erect unnecessary and sometimes illegal barriers to survivors’ job opportunities (Hoffman, 1999, 2004b). Most personnel decisions are driven by economic factors, not by charitable or personal consideration. Employers may be motivated to fire an employee with cancer (or a history of cancer) because of concerns about increased costs due to insurance expenses and lost productivity or because of concerns about the psychological impact of a survivor’s cancer history on other employees. Some employers may fail to revise their personnel policies to comply with new laws and, even among those with updated policies, employers may not train their personnel managers properly to comply with these laws. The interpretation of laws designed to prohibit discriminatory practices is sometimes unclear and is being resolved in the courts. Some employers and co-workers treat cancer survivors differently from other workers, in part because they have misconceptions about survivors’ abilities to work during and after cancer treatment (NCCS and Amgen, undated). In an effort to educate employers regarding their responsibilities to employees with cancer, Business and Health published a special report, “Living, Coping, and Working with Cancer.” A set of recommendations from a panel of health care and business experts convened by Business and Health is shown in Box 6-6.

Information, Support, and Referral

This section reviews sources of employment-related information, support, and referral available through employers, cancer voluntary organizations, consumer advocacy programs, and federal and state government programs. The next section reviews the provision of financial support (including health and disability insurance).

|

BOX 6-6

SOURCE: Business and Health Special Report (Voelker, 1999). |

The role of employers Employers may provide information, support, and referral services of relevance to cancer survivors through onsite health programs or workplace intranets. Several employers offer their employees web-based personal health management tools allowing them to get information and identify resources (Blumklotz and Lansky, 2001). Toll-free medical decision support services are available to employees to help them make better informed health care purchasing decisions. Cancer questions and requests for information lead all other health care inquiries at some of these programs (Lee, 2004). To help employees balance their personal and professional lives, some companies have provided so-called “work-life” programs offering flexible work options, elder care programs, employee assistance programs (EAPs), and health care and wellness programs (Center on an Aging Society, 2004). Such programs are of benefit to individuals undergoing cancer treatment or in need of flexible scheduling upon a return to work. Leave policies may be prescribed by law (see earlier section on the

Family and Medical Leave Act and related state laws), but some employers provide benefits that exceed those mandated.

Many employers in the private and public sectors have formal or informal disability management and return-to-work programs (Bruyere, 2000). EAPs address productivity issues by helping employees identify and resolve personal concerns that may affect job performance, including issues related to health, marriage, family, substance abuse, stress, and legal problems (Employee Assistance Professionals Organization, 2004). EAPs may provide one-on-one assistance, employee training programs, and leadership consultations. An estimated 56 percent of companies with more than 100 employees provide EAPs that address work-life issues (FWI, 1998; Center on an Aging Society, 2004). In an effort to increase the availability of psychosocial support for cancer patients, the Individual Cancer Assistance Network project (funded by the Bristol-Myers Squibb Foundation) has trained master’s-level counselors in EAPs and family service organizations located in Florida (Bristol-Myers Squibb, 2004; Alter, 2005).

It is important to note that employers cannot search records and then initiate contact with employees based on their health status, no matter how commendable their intentions (Lee, 2004). Such contact is prohibited by HIPAA.

Cancer voluntary organizations and consumer advocacy programs Several nonprofit cancer organizations provide education, counseling, and legal advice regarding employment to cancer survivors. The American Cancer Society (ACS) (2004a), the Lance Armstrong Foundation (LAF, 2004), the National Coalition for Cancer Survivorship (NCCS) (Hoffman, 2004a), and CancerCare (CancerCare, 2005), for example, provide information about employment concerns following a diagnosis of cancer.

A number of programs provide legal assistance to cancer survivors concerned about their employment and insurance rights (Box 6-7). For example, legal counseling and education and training for professionals and individuals with cancer are available through the Cancer Legal Resource Center, Western Law Center for Disability Rights. Supported in part by the California Division of ACS, callers to the ACS information line with legal questions are referred to the Center. In 2004 the Center served more than 3,000 callers and reached about 6,000 people through training and outreach. Approximately 13 percent of calls relate to employment, concerns about telling a new employer about cancer, expectations when going back to work, disclosure of cancer history when returning to work, and loss of a job (Schwerin, 2005). The Center serves individuals nationwide, and about half the people calling for assistance are from outside California.

CancerCare is a national nonprofit organization that provides free counseling (individual and group), education, information and referral, and

|

BOX 6-7 The Cancer and ALS Legal Initiative of the Atlanta Legal Aid Society provides free legal assistance to low-income persons living with cancer in the metro Atlanta area. Cancer Legal Resource Center provides information and educational outreach on cancer-related legal issues. Cancer Legal Services Project of the Bar Association of San Francisco provides free services directly to low-income people with cancer. Legal Advocacy for Cancer Patients at the Temple Legal Aid Office provides free attorney and advocate services to individuals in Philadelphia. Legal Information Network for Cancer provides legal assistance to individuals with cancer in central Virginia and referrals to attorneys who provide services on a sliding-scale basis. LegalHealth offers a comprehensive legal clinic onsite in New York area hospitals and at community-based organizations addressing the needs of chronically and seriously ill low-income New Yorkers. Training of doctors, social workers, and other medical professionals is also provided. SOURCES: Legal Information Network for Cancer (2004); Bar Association of San Francisco (2004); New York Legal Assistance Group (2004); ABA (2004). |

direct financial assistance to more than 90,000 people with cancer each year (Personal communication, C. Messner, CancerCare, September 22, 2004) (CancerCare, 2005).10 Staff oncology social workers and case managers address issues related to employment through a program called “Cancer in the Workplace,” where issues related to legal rights and reentering the workplace are discussed. CancerCare sponsors teleconferences regularly, including a series called “Strength for Caring: Living, Working, and Coping with Cancer” (Box 6-8). Some teleconferences are specifically for employers and are promoted through direct contact to companies and partnerships with other organizations. Human resources personnel are able to discuss employer responsibilities, accommodations, helping co-workers deal with colleagues with cancer, and how to interpret laws such as the FMLA and ADA. Teleconferences for patients and caregivers facilitate discussions on disclosure of cancer status to employers, physical examinations, and dealing with physical limitations at work. Caregiver rights under FMLA and ADA are also addressed.

|

BOX 6-8

SOURCE: CancerCare (2004). |

“Good Health for Life” is a program dedicated to getting cancer survivors back to work. Associated with Stanford University Medical Center, the program provides entrepreneurship resources for cancer survivors and educational programs for business and governments (Good Health for Life, 2004).

Federal and state government programs A number of education and referral programs offered by NCI address employment issues. For example, Life After Cancer Treatment, part of NCI’s “Facing Forward Series” of publications, describes federal sources of information regarding employment rights, disability, and discrimination (NCI, 2002). Survivors concerned about employment issues are referred to fact sheets and other information provided by the EEOC, the federal agency that coordinates the investigation of employment discrimination. Other federal sources of information and referral include the U.S. Department of Justice, which provides information to assist persons with disabilities with legal issues, questions about the ADA, mediation services, and other employment issues. The U.S. Department of Labor’s Office of Disability Employment Policy also provides information regarding discrimination, workplace accommodation, and legal rights. The Job Accommodation Network, a service of the U.S. Department of Labor, provides information on workplace accommodation to both employers and employees.

In addition to education and referral programs, 80 federally funded state vocational rehabilitation agencies employing more than 11,000 voca-

tional counselors throughout the United States provide direct services to facilitate a return to work (Personal communication, J. Pepin, U.S. Department of Education, Office of Special Education and Rehabilitation, September 24, 2004). As of 2003, 2,191 individuals with cancer had completed rehabilitation at one of these agencies. Nearly 60 percent of these cancer survivors, upon completion of the rehabilitation program, were placed in a job and worked for at least 90 days (Personal communication, P. Nash, U.S. Department of Education, Office of Special Education and Rehabilitation, September 22, 2004). Individuals with a history of cancer represent less than 1 percent of those served by the federal/state rehabilitation system. It is unclear why so few persons with cancer complete rehabilitation programs—it may be that cancer survivors do not need, desire, or qualify for the services or, alternatively, that they are not referred to, or accepted by, such programs (Conti, 1990; Mundy et al., 1992). The programs are required to prioritize service delivery to those with severe disabilities, and cancer survivors may not always meet eligibility requirements.

In summary, a number of employer, consumer advocacy organizations, and governmental programs are available to provide information, counseling, and rehabilitation services to address employment-related concerns of cancer survivors. There is little information regarding the extent to which cancer survivors or their providers are aware of these services, or use them. There appears to be a patchwork of services, and it is unclear how accessible they are across the country, how comprehensive the services are, and whether they are meeting the needs of cancer survivors.

Financial Assistance

Private short- and long-term disability insurance and disability programs of the Social Security Administration can be important sources of income replacement for cancer survivors who have had extended times away from work or who are disabled and can no longer work. This section briefly reviews these programs. Sources of financial assistance for individuals’ health-related expenditures are described in the next section of the chapter following a review of health insurance issues.

Short- and long-term disability insurance Private short- and long-term disability insurance can provide invaluable financial assistance to individuals who have exhausted their sick and annual leave at work. However, relatively few workers have employment-based disability benefits. In 2004, 39 percent of all workers in private industry had access to short-term disability benefits, other than paid sick leave, while 30 percent had access to long-term disability benefits. Access to these disability benefits is greater among higher wage earners and those working for large employers (Table 6-3).

TABLE 6-3 Percentage of Workers with Access to Disability Insurance Benefits, by Selected Characteristics, Private Industry, 2004

|

Characteristic |

Short-Term Disability Benefits |

Long-Term Disability Benefits |

|

All workers |

39 |

30 |

|

Worker characteristics |

||

|

White-collar occupations |

43 |

41 |

|

Blue-collar occupations |

45 |

22 |

|

Service occupations |

23 |

12 |

|

Full time |

47 |

38 |

|

Part time |

14 |

5 |

|

Union |

67 |

30 |

|

Nonunion |

36 |

30 |

|

Average wage <$15 per hour |

29 |

17 |

|

Average wage ≥$15 per hour |

55 |

48 |

|

Establishment characteristics |

||

|

Goods-producing |

54 |

31 |

|

Service-producing |

35 |

30 |

|

1-99 workers |

28 |

19 |

|

100 workers or more |

53 |

44 |

|

SOURCE: Bureau of Labor Statistics (2004). |

||

Short-term disability programs are required by law in some states (e.g., New Jersey, New York).

Federal Social Security Administration programs Since 1974, the Supplemental Security Income (SSI) program has guaranteed a minimum level of income for needy aged, blind, or disabled individuals (SSA, 2004b). To be considered disabled, an individual must have a medically determinable physical or mental impairment that is expected to last (or has lasted) at least 12 continuous months or to result in death. For those aged 18 and older, the impairment must prevent him or her from doing any substantial gainful activity. The SSI program was designed to provide “assistance of last resort.” It is means-tested and takes into account all income and resources that an individual has or can obtain. Generally, SSI recipients are immediately eligible for Medicaid. The program includes work incentives that

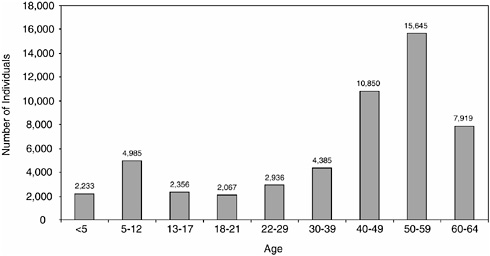

FIGURE 6-2 Number of SSI recipients eligible because of a cancer diagnosis, by age, December 2003. SOURCE: SSI Annual Statistical Report, 2003, Table 25 (SSA, 2004b).

enable recipients who are disabled to work and retain benefits and, in certain circumstances, extended Medicaid eligibility.

In December 2003, an estimated 53,376 individuals under age 65 were receiving SSI benefits because of a diagnosis of cancer. Cancer survivors represent only 1.1 percent of the total number of SSI recipients under age 65 (4.9 million) (Figure 6-2). Most SSI recipients under age 65 (58 percent) become eligible because of a mental disorder (SSA, 2004b). In December 2003, the average monthly federal SSI payment to beneficiaries with cancer was $404 (payment depends on income, and 45 states provide supplemental payments) (SSA, 2004b).

Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) is an insurance program that provides payments to persons with disabilities based on their history of Social Security-covered earnings. In contrast, the SSI program is a means-tested program that does not require prior participation in the labor force. The definition of disability and the process of determining disability are the same for both programs (IOM, 2002b). To be eligible, an individual must be unable to work at all, in any job, for at least 12 months or be in the terminal stages of illness. As of 2003, 160,986 disabled workers under age 65 were receiving SSDI payments because of cancer, representing 2.7 percent of all disabled workers receiving SSDI benefits (SSA, 2004a).

Summary: Employment Issues

It is difficult to gauge the extent of cancer-related employment problems, but recent evidence suggests that as many as 20 percent of survivors face work limitations 2 to 3 years after their diagnosis. Survivors appear to be most vulnerable in the immediate post-treatment period. A number of federal and state laws enacted in the 1990s provide some level of protection from employer discriminatory practices. However, these laws are not comprehensive and the courts continue to interpret the extent of protections provided to cancer survivors. A patchwork of educational, counseling, and referral sources is available. Unknown is whether cancer survivors are aware of their legal protections or of the services that are available to them. Limited financial assistance in the form of income replacement is available through the Social Security Administration to those who are poor and too disabled by cancer to work. Some individuals have some financial protection through short- and long-term disability programs, but these benefits tend to be offered by relatively few employers.

HEALTH INSURANCE

The Impact of Cancer on Health Insurance

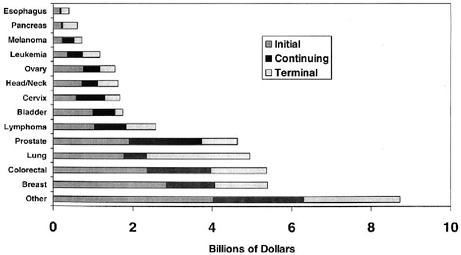

Cancer care is very costly and represents one of the three most expensive conditions in the United States (Cohen and Krauss, 2003). Cancer-related medical expenditures in the United States totaled an estimated $48 billion in 2002 (AHRQ, 2004).11 Although most cancer-related expenditures are for initial treatment, expenditures for continuing care are not insubstantial, especially for those cancers with good prognoses (Figure 6-3).

Most Americans have health insurance that provides coverage for most cancer-related care. However, the lack of health insurance for 42 million Americans has serious negative consequences and economic costs not only for the uninsured themselves, but also for their families, the communities they live in, and the nation as a whole (Cohen and Martinez, 2005; IOM, 2004a). The uninsured do not receive the care they need; they suffer from poorer health, and are more likely to die early than are those with coverage. Aside from the health consequences, even one uninsured person in a family can put the financial stability and health of the whole family at risk. Furthermore, a community’s high uninsured rate can adversely affect the over-

FIGURE 6-3 National U.S. Medicare expenditures in 1996 by cancer type and phase of care.

DATA SOURCE: SEER-Medicare database (Brown et al., 2002). Reprinted with permission from Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins. Brown ML, Riley GF, Schussler N, Etzioni R. 2002. Estimating health care costs related to cancer treatment from SEER-Medicare data. Med Care 40(8 Suppl):IV-104–IV-117.

all health status of the community and its health care institutions and providers, and the access of its residents to certain services. These are among the conclusions reached by the Institute of Medicine’s (IOM’s) Committee on the Consequences of Uninsurance in their 2004 report, Insuring America’s Health: Principles and Recommendations (IOM, 2004a).

Many studies link lack of health insurance with poor cancer outcomes (Ayanian et al., 1993; Lee-Feldstein et al., 2000; Ferrante et al., 2000; Roetzheim et al., 2000a,b; Penson et al., 2001; IOM, 2001, 2002a). Access to health insurance has been found to influence the amount and quality of health care received, which in turn is likely related to survival. Three-year relative cancer survival was markedly poorer for those without health insurance as compared to the insured, according to one state’s population-based study (Grann and Jacobson, 2003; McDavid et al., 2003). The link between insurance status and health outcomes is complex and confounded by socioeconomic status, race and ethnicity, and other factors. In one study, non-elderly cancer patients without insurance were found to be at risk for receiving inadequate cancer care, especially if they were Hispanic (Thorpe and Howard, 2003). Here, expenditures for uninsured patients under age 65 were nearly half (57 percent) that of privately insured patients over a 6-month period. Spending differences were believed to be due, in part or

completely, to differences in use, suggesting that raising coverage rates would improve cancer treatment. These findings are consistent with other studies of the chronically ill that have compared those with and without health insurance and found the uninsured lack needed physician care and prescription medicines (Families USA, 2001).

To overcome such health disparities, the IOM Committee on the Consequences of Uninsurance envisioned an approach to health insurance that would promote better overall health for individuals, families, communities, and the nation by providing financial access for everyone to necessary, appropriate, and effective health services. The committee articulated five principles to guide the extension of coverage (Box 6-9) and recommended that the President and Congress develop a strategy to achieve universal insurance coverage and to establish a firm and explicit schedule to reach this goal by 2010. Many plans to reform the nations’ health care insurance system have been proposed, and these principles are useful in assessing the relative merits of current proposals and in designing future strategies for extending coverage to everyone.

The IOM Committee on Cancer Survivorship agrees with the vision and implementation plan that has been put forth. Only through such an effort will cancer survivors, their families, and health care providers be able to fully focus on care and well-being without being burdened by financial worries. Although addressing national health care proposals to extend health insurance coverage to more Americans was not within the scope of the Committee on Cancer Survivorship’s work, the committee wishes to highlight in this report the serious consequences of lack of insurance coverage to cancer survivors, their families, and their caregivers. The actions recommended in the IOM’s insurance-focused work are endorsed by the Cancer Survivorship Committee.

|

BOX 6-9

SOURCE: IOM (2004a). |

TABLE 6-4 People Without Health Insurance Coverage by Age, United States, 2004

This section of the report begins with a description of the extent of the problem of lack of insurance coverage among cancer survivors and the limited remedies available to the uninsured who wish to gain health insurance coverage. Next, problems of cancer survivors with insurance are reviewed, including difficulties in maintaining health insurance coverage, gaining access to needed treatments and specialists, and paying health care out-of-pocket costs that stem from underinsurance (either due to insurance exclusions or benefit limits). In particular, the problem of paying for costly prescription medications is discussed. The limited number of programs to ameliorate financial hardships that result from uninsurance and underinsurance are described. Lastly, issues related to access to life insurance are briefly discussed.

As many as 15 percent of Americans lack health insurance (Table 6-4) and, for these individuals, cancer can be financially devastating. Among adults aged 45 to 64, an age when many develop cancer, 13 percent are uninsured. Adults aged 35 to 44 have even higher rates of being uninsured (18 percent). Vulnerability increases when measured over a longer timeframe. While 44 million Americans were uninsured in 2003, nearly twice that number, an estimated 84 million, were uninsured for at least 1 month over a 3-year period (Short et al., 2003). This, in part, reflects the dynamic nature of the population of the uninsured: About 2 million people become uninsured every month, while about the same number gain insurance (Short et al., 2003). Vulnerability also increases as health status declines. Research shows people in poor health are twice as likely to encounter a lengthy spell without health insurance compared to people in good health (Haley and Zuckerman, 2003).

The increase in the number of uninsured Americans in the past several years has been confined to adults, as public programs have expanded to offset the general decline in employer insurance for children. Among adults, loss of insurance can be traced to declines in employer-based insurance (DeNavas-Walt et al., 2004; Kaiser Family Foundation, 2004a). Employer-sponsored health insurance for retirees is also becoming less available, making it more difficult for survivors with significant health problems to retire early (American Benefits Council, 2004). Retirees are increasingly responsible for a larger share of the cost of their health care. Most uninsured adults had employer-based coverage prior to becoming uninsured. Several safety net laws and programs have been created to help people navigate coverage transitions and offer coverage to the uninsured. Although the protections offered by these laws and programs are important, they are incomplete. People with cancer can, and sometimes do, lose health insurance just when they need it most.

Much of the research that has documented insurance problems among cancer survivors was conducted prior to the enactment of laws to improve access to insurance coverage and protect consumers from some forms of discrimination. This literature documents instances of insurers refusing new applications, canceling or reducing policies, charging higher premiums, waiving or excluding preexisting conditions, or extending waiting periods for coverage (Kornblith, 1998; Guidry et al., 1998; Hoffman, 1999). Not much is known of the impact on contemporary cancer survivors of the relatively new federal and state laws that should facilitate obtaining and maintaining insurance coverage (Pollitz et al., 2000). What has been well documented are the very high costs associated with cancer and how such costs can serve as barriers to cancer care for both those with and those without health insurance (Guidry et al., 1998).

Cancer Survivors Who Are Uninsured

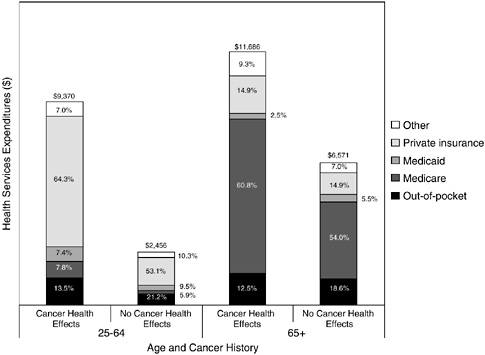

Virtually all (99 percent) cancer survivors aged 65 and older have health insurance coverage through the nation’s Medicare program.12 The problems the elderly have in coverage are discussed in the next section. With 39 percent of cancer survivors under age 65 and the potentially devastating impact of a cancer diagnosis on personal finances, the committee analyzed data from the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) (2000 to 2003) to answer several questions about health insurance coverage among nonelderly cancer survivors (see Appendix 6A for details on the NHIS and the methods used to derive these estimates).

|

12 |

This estimate is based on staff analyses of the National Health Interview Survey described in Table 6-5. |

-

How many nonelderly cancer survivors lack health insurance? Among cancer survivors ages 25 to 64, 11 percent are uninsured (approximately 572,000 individuals) (Table 6-5).

-

Which groups of cancer survivors are less likely to be insured? Lacking health insurance is more common among younger survivors (ages 25 to 44) (19 percent) and Hispanic/Latino survivors (26 percent) (Table 6-5).

-

To what extent do nonelderly cancer survivors rely on public health insurance programs? An estimated 14 percent of non-elderly cancer survivors depend on Medicare or Medicaid for coverage. Lack of insurance and reliance on public insurance coverage increase with years since diagnosis. Rates of private insurance coverage are higher for survivors with breast and prostate cancer. This could reflect differences in age distribution (older individuals are more likely to have health insurance) or perhaps indicate that those with insurance are more likely to be screened and then survive their cancer (Table 6-5).

-

How does the health insurance status of cancer survivors compare to that of the general population and to individuals with other chronic illnesses? The uninsured rate among nonelderly cancer survivors is no higher than those seen in the general population (it is lower, 11.3 percent versus 16.3 percent). This may, in part, be explained by the older age distribution of cancer survivors and the general trend of increasing rates of insurance coverage with age (Table 6-4). It could also reflect greater efforts to maintain coverage by those with a chronic illness as compared to healthy individuals. Alternatively, it may be the case that individuals without health insurance and access to primary health care are not represented among cancer survivors (see Chapter 2). Lacking insurance is a problem of similar magnitude for cancer survivors (11.3 percent) and those with cardiovascular disease (12.1 percent) and diabetes (12.6 percent). People with other chronic conditions that are more prevalent in younger populations (e.g., diabetes) also exhibit higher coverage rates, however. This suggests people with chronic conditions may take on greater burdens and make more sacrifices, such as job lock, to get and keep coverage, compared to healthy individuals who can navigate insurance transitions with less difficulty and expense.

-

To what extent does a lack of insurance coverage impede cancer survivors’ access to care? Among cancer survivors ages 25 to 64 and without health insurance, many report access problems due to concerns about cost—51 percent (291,000 individuals) report delays in obtaining medical care; 44 percent (250,000 individuals) report not getting needed care; and 31 percent (178,000 individuals) report not getting needed prescription medicine. Similar consequences of a lack of coverage have been documented among those with other chronic illnesses (Tu, 2004).

TABLE 6-5 Health Insurance Status of Cancer Survivors Ages 25 to 64, by Selected Characteristics, 2000–2003

|

Characteristic |

Estimated Population |

|

|

In Millions |

% |

|

|

Total |

5.0 |

100.0 |

|

Age |

||

|

25–44 |

1.5 |

30.6 |

|

45–64 |

3.5 |

69.4 |

|

Sex |

||

|

Male |

1.5 |

29.8 |

|

Female |

3.5 |

70.2 |

|

Race/ethnicity |

||

|

White, non-Hispanic |

4.3 |

85.3 |

|

Hispanic |

0.3 |

5.2 |

|

Black, non-Hispanic |

0.4 |

7.1 |

|

Other |

0.1 |

2.3 |

|

Years since diagnosis |

||

|

<2 |

0.8 |

16.6 |

|

2–4 |

1.2 |

23.7 |

|

5–9 |

1.1 |

21.3 |

|

10–19 |

1.2 |

24.0 |

|

20+ |

0.7 |

14.5 |

|

Age at interview, age at diagnosis |

||

|

25–44, <45 |

1.5 |

30.7 |

|

45–64, <45 |

1.5 |

29.0 |

|

45–64, 45–64 |

2.0 |

40.3 |

|

Cancer type |

||

|

Female breast |

1.0 |

19.4 |

|

Female reproductivea |

1.5 |

29.7 |

|

Prostate |

0.2 |

4.7 |

|

Colorectal |

0.3 |

5.9 |

|

Other |

2.0 |

40.3 |

|

Has other chronic disease |

||

|

Yes |

1.8 |

35.1 |

|

No |

3.3 |

64.9 |

|

Self-reported health status |

||

|

Excellent/very good |

2.1 |

41.5 |

|

Good |

1.5 |

30.5 |

|

Fair/poor |

1.4 |

28.0 |

|

NOTE:—indicates too few cases for reliable estimate. The NHIS estimate of the number of cancer survivors ages 25 to 64 (5 million) is somewhat higher than that estimated from surveillance data (4 million). This could be explained if there is overreporting of a cancer history among those ages 25 to 64 and interviewed for the NHIS. |

||

|

Health Insurance Status (percentage distribution) |

||||

|

Medicare |

Medicaid |

Private |

Other Coverage |

Uninsured |

|

7.4 |

6.8 |

70.6 |

3.9 |

11.3 |

|

3.5 |

9.2 |

65.3 |

3.6 |

18.5 |

|

9.1 |

5.8 |

72.9 |

4.1 |

8.2 |

|

10.5 |

5.1 |

70.9 |

5.2 |

8.3 |

|

6.0 |

7.6 |

70.5 |

3.4 |

12.6 |

|

7.1 |

5.8 |

73.2 |

4.0 |

10.0 |

|

— |

10.2 |

56.4 |

— |

25.8 |

|

10.0 |

14.1 |

56.0 |

— |

15.0 |

|

— |

— |

52.5 |

— |

— |

|

— |

6.4 |

76.0 |

— |

7.9 |

|

6.3 |

6.5 |

75.2 |

— |

9.5 |

|

8.3 |

7.1 |

68.7 |

4.3 |

11.5 |

|

8.8 |

7.2 |

67.1 |

— |

13.1 |

|

7.6 |

7.1 |

66.3 |

— |

14.7 |

|

3.3 |

9.3 |

65.3 |

3.5 |

18.6 |

|

7.9 |

6.3 |

71.4 |

3.4 |

11.0 |

|

9.9 |

5.5 |

74.3 |

4.4 |

5.9 |

|

6.3 |

5.1 |

80.2 |

— |

5.4 |

|

4.9 |

10.6 |

61.8 |

4.0 |

18.7 |

|

— |

— |

80.0 |

— |

— |

|

— |

— |

72.0 |

— |

— |

|

9.4 |

5.5 |

71.1 |

3.8 |

10.2 |

|

15.2 |

11.2 |

56.2 |

5.3 |

12.1 |

|

3.1 |

4.5 |

78.3 |

3.2 |

10.9 |

|

— |

— |

84.2 |

2.6 |

10.2 |

|

4.0 |

5.6 |

74.6 |

3.7 |

12.1 |

|

20.1 |

15.9 |

45.6 |

6.2 |

12.1 |

|

aFemale reproductive cancer includes cancer of the cervix, uterus, and ovary. SOURCE: NHIS tabulations, committee staff. See Appendix 6A for a description of the NHIS and the methods used to derive these estimates. |

||||

These estimates of health insurance coverage among cancer survivors are based on a national survey and have limitations. First, the results pertain only to the adult civilian noninstitutionalized household population and not to cancer survivors who reside in institutions (e.g., hospices or nursing homes). The NHIS interviews rely on self-reports of cancer, and such reports tend to underestimate cancer prevalence (Hewitt et al., 1999; Desai et al., 2001). Furthermore, the survey is cross-sectional and does not capture the dynamic nature of insurance coverage status.