7

Research

The emergence of survivorship research represents a change in focus for cancer research—from a focus largely on cure to one including longer term issues of morbidity and the quality of life of cancer survivors (Aziz, 2002, 2004). This chapter describes survivorship research in terms of its scope, methodologies for its conduct, the challenges it poses to investigators, and available sources of support. The chapter concludes with the committee’s identification of priority areas for research and recommendations for improving what we know about cancer survivors and their health care.

SURVIVORSHIP RESEARCH

The goal of survivorship research is to understand, and thereby reduce, the adverse effects of cancer diagnosis and treatment and to optimize outcomes for cancer survivors and their families (Aziz, 2002, 2004). Treatment effects, follow-up care, economic sequelae, health disparities, and family and caregiver issues are among the domains of survivorship research (Table 7-1). Survivorship research has in the past decade evolved from small, single-investigator, hypothesis-generating studies relying on convenience samples to interdisciplinary, rigorous tests of interventions through clinical trials. Research efforts have also broadened to begin to examine issues of concern to the full range of cancer survivors, with attention to ethnic and racial minorities, the elderly, rural residents, and those with rare cancers (Aziz, 2004). As Table 7-1 illustrates, a variety of research methods, both qualitative and quantitative, can be applied to this field. The increased

TABLE 7-1 Domains of Cancer Survivorship Research

|

Survivorship Research Domain |

Definition and Potential Research Foci |

|

Descriptive and analytic research |

Documenting for diverse cancer sites the prevalence and incidence of physiologic and psychosocial late effects, second cancers, and their associated risk factors Determining physiologic outcomes of interest, including late and long-term medical effects such as cardiac or endocrine dysfunction, premature menopause, and the effects of other comorbidities on these adverse outcomes Measuring psychosocial outcomes of interest, including the longitudinal evaluation of survivors’ quality of life, coping and resilience, and spiritual growth |

|

Intervention research |

Examining strategies that can prevent or diminish adverse physiologic or psychosocial sequelae of cancer survivorship Elucidating the impact of specific interventions (psychosocial, behavioral, or medical) on subsequent health outcomes or health practices |

|

Examination of survivorship sequelae for understudied cancer sites |

Examining the physiologic, psychosocial, and economic outcomes among survivors of colorectal, head and neck, hematologic, lung, or other understudied sites |

|

Follow-up care and surveillance |

Elucidating whether the timely introduction of optimal treatment strategies can prevent or control late effects Evaluating the effectiveness of follow-up care clinics/programs in detecting recurrence of the index cancer, detecting new primary cancers, and preventing or ameliorating long-term effects of cancer and its treatment, thereby increasing duration of life and quality of life Evaluating alternative surveillance strategies and models of follow-up care for cancer survivors that take into account cultural expectations, patient preference, insurance status, and other factors Developing a consistent, standardized model of service delivery for cancer-related follow-up care across cancer centers and community oncology practices Assessing optimal quality, content, frequency, setting, and provider of follow-up care for survivors |

|

Economic sequelae |

Examining the economic effects of cancer for the survivor and family and the health and quality of life outcomes resulting from diverse patterns of care and service delivery settings |

|

Survivorship Research Domain |

Definition and Potential Research Foci |

|

Health disparities |

Elucidating similarities and differences in the survivorship experience across diverse diagnostic, race, ethnic, gender, and socioeconomic groups Examining the potential role of ethnicity in influencing the quality and length of survival from cancer |

|

Family and caregiver issues |

Exploring the impact of cancer diagnosis in a loved one on the family and the impact of family and caregivers on survivors |

|

Instrument development |

Developing instruments capable of collecting valid data on survivorship outcomes, specifically for survivors beyond the acute cancer treatment period Developing/testing tools to evaluate long-term survivorship outcomes that (1) are sensitive to change, (2) include domains of relevance to long-term survivorship, and (3) will permit comparison of survivors to groups of individuals without a cancer history and/or with other chronic diseases over time Identifying criteria or cutoff scores for qualifying a change in function as being clinically significant |

|

SOURCE: Adapted from Aziz and Rowland (2003). |

|

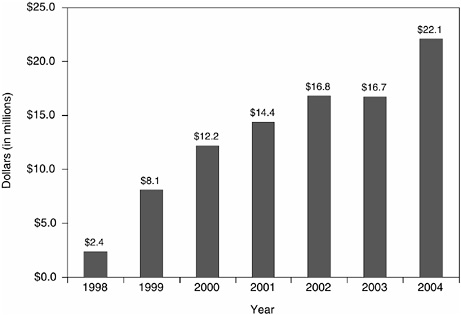

sophistication and breadth of survivorship research can be traced largely to a prioritization by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) of survivorship research and the establishment in 1996 of the NCI’s Office of Cancer Survivorship (NCI Director, 2002, 2003; Aziz, 2004). Trends in research publications indicate an increased level of activity within this relatively new discipline (Figure 7-1).

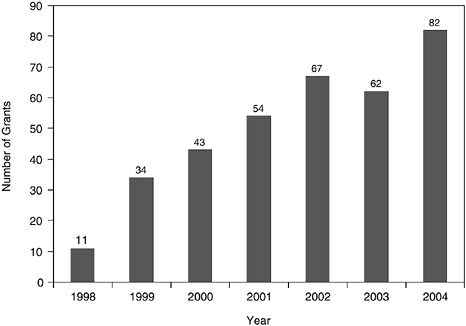

Despite the apparent growth in research productivity, the volume of cancer survivorship research is dwarfed by research aimed at cancer treatment (Figure 7-2). The recent emergence of the discipline and the modest levels of research support relative to that available for treatment-related research (see discussion below) may explain some of the difference in research activity. Inherent challenges of the research itself—for example, the need for extended periods of follow-up—may also account for the observed differences (see discussion below).

FIGURE 7-1 PubMed citations for adult cancer survivorship research, 1992–2004.

FIGURE 7-2 PubMed citations for adult cancer treatment research, 1992–2004.

NOTE: The National Library of Medicine’s PubMed database includes citations from MedLine, HealthStar, and other bibliographic databases. The database stores information about individual citations, including index terms used to characterize each article (articles are indexed according to a dictionary of medical subject headings called MeSH terms). Citations were identified using the MeSH terms “neoplasms” and “survivors,” and keywords (e.g., survivor, survivorship, late effects, long-term effects), excluding citations categorized under the MeSH terms “child,” “adolescent,” “infant,” “child, preschool,” or “pediatrics.” The MeSH heading “survivors” refers to “persons who have experienced a prolonged survival after serious disease or who continue to live with a usually life-threatening condition as well as family members, significant others, or individuals surviving traumatic life events” (NLM, 2004). Citations were limited to those pertaining to “humans” and published in English. There would be an underestimate of survivorship-related citations if the “survivors” MeSH term was not applied by abstractors to the citations or if the title and abstracts of articles varied in their inclusion of keywords.

SOURCE: National Library of Medicine’s PubMed database (NLM, 2005).

MECHANISMS FOR CONDUCTING RESEARCH

Survivorship-related research is often conducted through several mechanisms—clinical trials, cohort studies and analyses of cancer registries, administrative data, and surveys. This section of the chapter briefly describes these research mechanisms. The next section of the chapter enumerates some of the challenges investigators face in conducting survivorship research.

Clinical Trials

Much has been learned about the late effects of cancer treatment through long-term follow-up of participants enrolled in clinical trials of cancer treatments (Fairclough et al., 1999; Ganz et al., 2003b). In addition, clinical trials are conducted to test interventions to prevent treatment late effects among survivors of adult cancer and to test treatments for late effects (Table 7-2). Many of these survivorship-related trials are supported by the NCI through its Clinical Trials Cooperative Group Program, whose purpose is to develop and conduct large-scale trials in multi-institutional settings. There are currently 12 NCI-supported Cooperative Groups, 11 for adult malignancies and 1 for childhood cancer. This program involves more than 1,700 institutions and enrolls more than 22,000 new patients into cancer treatment clinical trials each year (NCI, 2003b).

Cancer clinical trials in the United States have focused on primary treatment, with relatively few trials examining supportive care, and none examining surveillance strategies (Table 7-3). An analysis of NCI-sponsored clinical trials on symptom management from 1987 to 2004 found relatively few trials with a primary end point related to late effects (e.g., hot flashes, cognitive function, osteoporosis) (Buchanan et al., 2005). Most such trials were focused on immediate symptoms of treatment (e.g., cachexia, pain). Relatively few clinical trials have assessed the appropriateness of follow-up strategies for individuals with cancer, and most of them have been conducted in Europe (see Chapter 3).

Cohort Studies

Cohort studies assess the experience of a group of individuals with a common characteristic, for example, a cancer diagnosis or a particular type of treatment. The cohort may be identified currently and followed up prospectively, or identified retrospectively with subsequent evaluation of health status. Cohorts of individuals with cancer diagnoses have been identified from cancer registries and asked to participate in special studies. Four examples of this approach include the American Cancer Society’s (ACS’s)

Study of Cancer Survivors, the NCI’s Prostate Cancer Outcomes Study, the Cancer of the Prostate Strategic Urologic Research Endeavor (CaPSURE), and studies of the NCI-sponsored Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance (CanCORS) Consortium. Cohorts may also be identified from patients treated at cancer centers. Two examples of such efforts are the long-term follow-up experience of individuals with Hodgkin’s disease who were treated at Stanford University Medical Center in California and a collaborative study of a cohort of survivors of childhood cancer. Although survivors of childhood cancer are not the focus of this study,1 the cohort study of childhood cancer is described here because it can possibly serve as a model for a comparable study of adult cancer survivors.

ACS Study of Cancer Survivors

The ACS’s intramural Behavioral Research Center is conducting two surveys of cancer survivors. The first is the Study of Cancer Survivors–I (SCS–I), a longitudinal study of quality of life of adult cancer survivors. Participating survivors complete questionnaires at 1, 2, 5, and 10 years after diagnosis, allowing a comparison of changes over time and an assessment of the long-term impact of cancer on survivors. The study’s sample includes adults diagnosed with 1 of 10 common cancers (breast, prostate, lung, colorectal, bladder, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, cutaneous melanoma, kidney, ovarian, and uterine). SCS-I also includes a family caregiver research component to explore the impact of the family’s involvement in cancer care on the quality of life of the cancer survivor and the caregiver.

The second survey of cancer survivors is the Study of Cancer Survivors–II (SCS–II), a national cross-sectional study of 2-, 5-, and 10-year cancer survivors that also focuses on quality of life. Survivors of breast, prostate, colorectal, bladder, cutaneous melanoma, and uterine cancer are participating in this study. The results will provide a basis for advocacy and planning by the ACS as well as by other health organizations and agencies.

The participants in both studies are selected with the cooperation of state cancer registries from the lists they maintain of people diagnosed with cancer. As of 2005, nearly 10,000 participants had been enrolled in the combined studies. Preliminary analyses of the cross-sectional data have provided information on the quality of life problems faced by survivors. The SCS–II study is expected to complete accrual of participants in the spring of 2005, while SCS–I will continue for several years.

TABLE 7-2 Examples of Clinical Trials of Relevance to Survivors of Adult Cancers

|

Topic |

Trial |

Sponsor |

Phasea |

|

Preventing the late effects of treatment |

|||

|

Sense of taste |

Zinc sulfate in preventing loss of sense of taste in patients undergoing radiation therapy for head and neck cancer |

North Central Cancer Treatment Cooperative Group |

III |

|

Bone loss |

Zoledronate, calcium, and vitamin D in preventing bone loss in women receiving adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer |

Cancer and Leukemia Cooperative Group B |

III |

|

Ovarian failure |

Goserelin in preventing ovarian failure in women receiving adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer |

Southwest Oncology Cooperative Group |

III |

|

Lymphedema |

Fibrin sealant in decreasing lymphedema following surgery to remove lymph nodes in patients with cancer of the vulva |

Gynecologic Oncology Cooperative Group |

III |

|

Treating or ameliorating late effects |

|||

|

Peripheral neuropathy |

Amifostine in treating peripheral neuropathy in patients who have received chemotherapy for gynecologic malignancy |

Gynecologic Oncology Cooperative Group |

III |

|

Depression |

Sertraline compared with hypericum perforatum (St. John’s Wort) in treating mild to moderate depression in patients with cancer |

Comprehensive Cancer Center of Wake Forest University |

III |

TABLE 7-3 Cancer Clinical Trials

The Prostate Cancer Outcomes Study

The Prostate Cancer Outcomes Study examined health and quality of life outcomes after prostatectomy or radiotherapy for prostate cancer (Potosky et al., 2000; Potosky et al., 2004; Johnson et al., 2004). For this study, a socioeconomically heterogeneous cohort of more than 1,500 newly diagnosed prostate cancer patients treated in community medical practices was selected from six Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) cancer registries. Men selected for the study were asked to complete and mail back questionnaires that covered disease-specific and general quality of life, and satisfaction and regret about treatment decisions. Surveys were completed at 6 months and 1, 2, and 5 years after diagnosis. Outpatient medical records were abstracted to obtain information on prostate-specific antigen (PSA) values, Gleason score,2 and details of initial treatment. At 2 and at 5 years of follow-up, important differences in urinary, bowel, and sexual functions were identified by treatment group and by race/ethnicity. This NCI-supported special study is estimated to have cost $7.5 million over the 10-year study period.

Cancer of the Prostate Strategic Urologic Research Endeavor

CaPSURE is an industry-supported national disease registry of more than 11,000 men with prostate cancer accrued at 31 primarily community-based sites across the United States (Cooperberg et al., 2004; CaPSURE, 2005b). The disease registry was founded in 1995. Since then investigators have used it to assess disease management trends, resource utilization, and health and quality of life outcomes (Box 7-1).

At each practice site all men with biopsy-proven prostate cancer are invited to join CaPSURE. Clinical information is collected at baseline and each time the patient returns for care. At each clinic visit, the treating urologist completes a progress record, including current disease status, new prostate or unrelated diagnoses, disease signs and symptoms, and changes in medications. At enrollment each patient completes a questionnaire addressing sociodemographic parameters, comorbidities, and health-related quality of life. Every 6 months thereafter patients are asked to complete a follow-up questionnaire to report on their quality of life, health care utilization, and since 1999 their level of satisfaction with care and degree of fear of cancer recurrence. Patients are followed until death or study withdrawal.

Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance

The CanCORS Consortium involves eight teams of investigators from around the United States who evaluate the quality of cancer care delivered

|

BOX 7-1

SOURCE: CaPSURE (2005a). |

and assess outcomes for approximately 10,000 newly diagnosed patients with lung and colorectal cancer (Ayanian et al., 2004) (Personal communication, A. Potosky, NCI, March 7, 2005). Individuals with cancer identified through cancer registries are being assessed at 4 to 6 months and at 13 months as part of this study sponsored by the NCI and the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). Longer term follow-up will be possible if additional grant funding is forthcoming. A caregiver supplement is being administered at some sites. CanCORS grantees will receive a total of approximately $34 million over the 5-year study period. The two principal research aims of the consortium are to: (1) determine how the characteristics and beliefs of cancer patients and providers, and the characteristics of health care organizations, influence treatments and outcomes, spanning the continuum of cancer care from diagnosis to recovery or death; and (2) evaluate the effects of specific therapies on patients’ survival, quality of life, and satisfaction with care, supplementing rather than substituting for data from randomized clinical trials (Ayanian et al., 2004).

The Stanford Hodgkin’s Disease Experience

Between 1960 and 1999, more than 3,000 patients with Hodgkin’s disease were seen, treated, and followed at Stanford University Medical Center (Personal communication, S. Donaldson, Stanford University, January 17, 2005) (Donaldson et al., 1999). This cohort includes patients of all ages and stages of disease and has provided information on the survival, mortality, and morbidity experience related to Hodgkin’s disease over four decades. Evidence of the high risk of cardiovascular late effects of treatment for Hodgkin’s disease emerged in the early 1990s from a special study of the Stanford cohort. Subsequent modifications in patient management and treatment have contributed to a reduction in this serious late effect. Evaluations of the risk of second cancers among this cohort have provided female cancer survivors of Hodgkin’s disease and their clinicians with information on the high risk of post-radiation breast cancer and the need for close surveillance with mammography. The Stanford follow-up program has not had core financial support. The cost of long-term follow-up is substantial and has only been partly offset by grant support. Payment for special studies, tests, and examinations has depended on unstable support.

The Childhood Cancer Survivor Study (CCSS)

Survivors of childhood cancer face both short- and long-term adverse outcomes as a result of their cancer and its treatment. In the early 1990s, studies of the late effects of childhood cancer were typically limited in

|

BOX 7-2

SOURCE: University of Minnesota Cancer Center (2002). |

sample size, duration of follow-up, and rigor (e.g., low participation rates, high rates of loss to follow-up, lack of appropriate comparison populations, imprecise assessment or quantification of cancer-related treatments). To address these limitations, the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study was established with support from the NCI in 1993 (University of Minnesota Cancer Center, 2002; Robison et al., 2002). The CCSS consortium consists of 26 participating clinical centers in the United States and Canada. A cohort of more than 14,000 5-year survivors of childhood and adolescent cancer has been assembled.

Study participants have completed a baseline and two comprehensive self-administered questionnaires and consented to release their medical records and to be contacted in the future. Nearly 4,000 siblings have been identified to serve as a control group. CCSS investigators have examined issues related to late effects, quality of life, health-related behaviors, and patterns of medical care use in an attempt to develop prevention strategies and to assess follow-up needs (Box 7-2).

In addition to continuing to collect follow-up data from participants, the study is collecting biologic materials, including tumor specimens from participants who develop subsequent cancers; buccal (cheek) cells from all participants, including siblings, as a source of genomic DNA; and peripheral blood samples from a subset of survivors to establish cell lines as a source of genomic DNA and RNA. These materials will be used to evaluate the role of genetics in the occurrence of cancer and long-term adverse

outcomes among survivors (University of Minnesota Cancer Center, 2002). Proposals to utilize the CCSS cohort can be submitted by any investigator, whether or not they have been directly involved with the study. Proposals that require direct contact with cohort members or that use banked biological materials require additional review.

Educational activities for study participants include access to the study website, a semi-annual newsletter, informational brochures targeted to subgroups at risk for particular late effects, and contact with investigators through e-mail and a toll-free telephone number. Intervention studies may also provide educational opportunities. For example, a smoking cessation study being conducted in the CCSS cohort is using a peer counseling approach that may have broad application to the cohort.

The CCSS investigators have described the far-reaching significance of its study for participants, health care providers, and scientists (University of Minnesota Cancer Center, 2002):

-

For study participants, the CCSS can improve their understanding of the consequences of their disease and treatment and their ability to make informed choices regarding health behaviors.

-

For current and future cancer patients, the study can help lead to improvements in treatment protocols that will minimize adverse health effects of therapy.

-

For physicians involved with the care of children with malignant disease, knowledge of late effects of therapy is critical to the design and choice of optimal cancer treatment regimens.

-

For health care providers and planners, the study offers the first opportunity to quantitatively assess the impact of long-term cancer survivorship on the delivery of care.

-

For epidemiologists and biologists, the CCSS is a resource to investigate current and emerging questions regarding consequences of therapy, genetic associations, disease processes and causation, and the quality of life of survivors.

Cancer Registries, Administrative Data, and Surveys

A great deal has been learned about the delivery of cancer care from studies that link two or more complementary data sources. The linkage of cancer registry data to insurance claims databases, for example, has provided evidence of significant geographic variations in care (IOM, 2000). Registry data contain useful measures of severity of cancer (e.g., cancer stage) and date of diagnosis, but may lack complete information on treatment and outcomes. Claims-based data may lack certain diagnostic information, but include detailed information on the cost and use of medical

services. Linkages between these two types of data sources allow the evaluation of large, relatively unbiased population-based samples of patients. Claims data are routinely collected, usually in a computer-readable format, and are therefore relatively easily and inexpensively accessible. However, there are limitations associated with claims data. Claims data are not collected for research, and coding misspecification and errors are common. Moreover, although registries can accurately document presenting cancer stage, they are less reliable for capturing recurrence. Consequently, algorithms that rely on information from claims must be used to identify cancer-free survivors—individuals who have survived their treatment, and have not had their cancer recur.

SEER-Medicare Linked Data

One of the most fruitful linkages for cancer care assessment is that of the SEER cancer registries to claims records in Medicare’s administrative database (Potosky et al., 1993; Warren et al., 2002). This is a collaborative effort of the NCI, the SEER registries, and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) to create a large population-based source of information for cancer-related epidemiologic and health services research. The SEER-Medicare data offer an opportunity to examine patterns of care prior to the diagnosis of cancer, during the period of initial diagnosis, and during long-term follow-up. Topics that can be addressed with the linked database include patterns of care for specific cancers, health care disparities, and the costs of care. Important findings on the quality of survivorship care have come from analyses of the SEER-Medicare data (Nattinger et al., 2002). Examples of recent survivorship research conducted with SEER-Medicare are shown in Box 7-3.

The linkage of the SEER-Medicare data was first completed in 1991 and is updated every 3 years. The most recent linkage in 2002 included the registries that were part of the SEER program as of 1999. These registries are located in 11 geographic areas, representing 14 percent of the U.S. population. With the 2005 linkage, the SEER-Medicare data will include the four expansion registries, and will then represent 26 percent of the U.S. population (NCI, 2004a).3 The Medicare utilization data (claims) cover stays in institutions (i.e., hospitals and skilled nursing facilities), physician and lab services, hospital outpatient visits, and home health and hospice

|

BOX 7-3 Morbidity

Patterns of Care

Costs of Care

Methodologic Studies

SOURCE: NCI (2004f). |

use. Information on noncovered services such as prescription drugs and long-term care is not yet available. The linkage was first completed in 1991 and has been updated most recently in 2003 (NCI, 2004e). The annual cost of maintaining the linked SEER-Medicare database is approximately $500,000.

State and Local Cancer Registries

State cancer registry data have also been linked to administrative records to assess survivorship care. For example, investigators linked state cancer registry data to health insurance claims from Blue Cross/Blue Shield of Virginia to assess adherence to standards of care for women with breast cancer (Hillner et al., 1997). More than three-quarters (79 percent) of women get a follow-up mammogram within the first 18 months postoperatively, according to this study. State cancer registries have also been linked to Medicaid data to examine the experience of Medicaid enrollees diagnosed with cancer (Bradley et al., 2003).

Other survivorship research has relied on hospital cancer registries to identify cohorts of individuals to follow prospectively (Pakilit et al., 2001; Ganz et al., 2002, 2003a). The American Society of Clinical Oncology’s National Initiative on Cancer Care Quality (NICCQ) identified subjects by using the National Cancer Data Base, a national registry of incident cancer cases, and its network of hospital cancer registries.4 Included in the study were a few measures related to the quality of survivorship care (e.g., receipt of tamoxifen for 5 years for certain women with breast cancer, receipt of counseling about the need for first-degree relatives of certain patients with colorectal cancer to undergo screening for this type of cancer) (Schneider et al., 2004).

NCI’s Cancer Research Network (CRN)

Some studies of cancer survivorship, including those based on SEER-Medicare data, exclude members of managed care organizations because such plans often do not have to report encounter data (e.g., individual claims for visits or services) to Medicare. Such plans insure approximately

15 percent of the Medicare-eligible population and cover the majority of commercially insured Americans. The Cancer Research Network, an initiative of the NCI, encourages the expansion of collaborative cancer research among health care provider organizations that are oriented to community care and have access to large, stable, and diverse patient populations. Collaborating investigators are able to take advantage of existing integrated databases that can provide patient-level information relevant to research studies on cancer control and to cancer-related population studies. Beginning in 1999, the NCI funded the CRN—a consortium of large, not-for-profit, research-oriented health maintenance organizations (HMOs). The CRN, now cooperatively funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), includes 11 HMOs nationwide that provide care for nearly 9 million enrollees. The proportion of HMO enrollees diagnosed with cancer who remain enrolled and available for CRN research projects is high. Retention rates of enrollees diagnosed with cancer within five of the CRN HMOs was 96 percent at 1 year and 84 percent at 5 years following diagnosis (Field et al., 2004). CRN investigators have proposed to study long-term survivors of colorectal cancer to assess the interrelationship among aspects of their initial care and subsequent physical, functional, and psychological outcomes (NCI, 2004b). CRN is also conducting a study, with a grant from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), of patient-oriented outcomes among women who have had prophylactic mastectomy. Although evidence suggests that a substantial reduction in breast cancer risk occurs after prophylactic mastectomy, its effect on other patient-oriented outcomes is unclear. This study will address this deficiency by gathering information from women identified for an ongoing study of the efficacy of prophylactic mastectomy in six HMO community-based populations across the United States (NCI, 2005a). A cancer survivorship group and a quality of cancer care special interest group have been convened within CRN to develop research proposals, and there are plans to survey cancer patients about their care experiences, particularly care coordination (Geiger, 2004) (Personal communication, S. Green, Group Health Cooperative, March 5, 2005). Core CRN support (excluding affiliated individual investigator awards, supplements, and other funding mechanisms) is $20 million over 4 years, 2003 to 2007 (Personal communication, S. Green, Group Health Cooperative, March 5, 2005).

Federal Health Surveys and Data

The results from federally sponsored surveys and other data collection activities provide national estimates of health indicators such as the prevalence of health conditions, the use of health care services, and health care

expenditures. Such surveys have been invaluable in estimating the prevalence of cancer risk behaviors (e.g., smoking), use of preventive health services (e.g., mammography), and use of supportive care services (e.g., mental health services). Federal surveys conducted of individuals are often very large, including members of as many as 50,000 households. With the prevalence of cancer estimated to be 3.5 percent, a sufficiently large, nationally representative sample of cancer survivors may be identified for study through such surveys.

In 1992 the NCI included a cancer survivorship section in the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) to obtain population-based estimates on aspects of the medical, insurance, and employment experiences of cancer survivors (Hewitt et al., 1999). Subsequent analyses of the NHIS have provided estimates of health status, health service use, and burden of illness among cancer survivors (Hewitt and Rowland, 2002; Hewitt et al., 2003; Yabroff et al., 2004). The Medical Expenditure Panel Survey has been used to estimate health insurance and spending among cancer patients (Center on an Aging Society, 2002; Thorpe and Howard, 2003). These household surveys exclude residents of institutions and therefore miss individuals with cancer who are in nursing homes, hospices, or other facilities. There are also limitations in self-reports of cancer. Evidence suggests, for example, that some individuals do not accurately report the occurrence of cancer or the type of cancer diagnosed (Chambers et al., 1976; Bergmann et al., 1998).

Summary

Investigators have used a number of research mechanisms to learn about the health and quality of life of cancer survivors. Information about patterns of care and the quality of survivorship care have been forthcoming from existing data resources such as cancer registries linked to administrative records. Long-term prospective studies of cancer survivors have been conducted based on samples drawn from cancer registries and from cancer centers. There are examples of survivorship studies being incorporated into the NCI’s cooperative group system treatment trials, but opportunities to use this infrastructure to further survivorship research have not been fully realized. No clinical trials of adequate design and sufficient size to judge the appropriateness of surveillance strategies for cancer survivors have been conducted in the United States.

CHALLENGES OF SURVIVORSHIP RESEARCH

Survivorship research is by nature challenging (Ganz, 2003). Late effects may not emerge for decades, necessitating prolonged follow-up. In

addition, the constant evolution of diagnostic tests and cancer treatments, although desirable, means that studies of late effects must be ongoing. A frustration for patients is that research on the late effects of therapies they are considering may not be available to them when they are making treatment decisions. Cancer is predominantly a disease of the elderly, so another challenge to survivorship researchers is to design studies that can isolate the effects of cancer and its treatment from the symptoms and disabilities expected from normal aging and the onset of comorbid conditions. Some of the specific challenges of survivorship research are highlighted below, including those related to long-term follow-up and the need to accrue large and diverse patient populations. In addition, some administrative issues are described that are faced by researchers in general, but are of particular concern to survivorship investigators, including those related to informed consent and assuring privacy of medical records.

Long-Term Follow-up

Because ongoing surveillance is needed to identify late effects, survivorship researchers often need to follow individuals for lengthy periods. During follow-up, participants may move, change doctors or health plans, tire of being a research subject, or become too sick to answer questions or submit to examinations. When research subjects are “lost to follow-up,” investigators’ ability to reach conclusions about the significance of symptoms that may have been identified during the follow-up period are diminished (Sears et al., 2003). Investigators have reported particular difficulties in collecting quality of life data in longitudinal studies of clinical trial participants (Moinpour and Lovato, 1998; Bernhard et al., 1998). Most research has focused on the early survivorship period (within 2 years of diagnosis) despite the increasing number of cancer survivors living 5 years or more after a cancer diagnosis (Aziz and Rowland, 2003). Research studies with extended follow-up periods are needed to identify recurrent cancer, new primary cancers, and the many late effects that have long latency periods.

Long-term follow-up is labor intensive, and studies of late effects can be very expensive. Biomedical tests to document physiological and functional impairments (cardiac and pulmonary tests, cognitive functioning and brain imaging studies) are expensive, but are necessary to detect subclinical disease that can put patients at risk. Even periodic assessments of quality of life following cancer treatment can be expensive. In one study, conducted in 1995, quality of life assessments added approximately $7,000 to the average monthly direct cost of a clinical trial (Moinpour, 1996). One of the major reasons for this is keeping track of patients.

Researchers have called for the establishment of mechanisms to facili-

tate monitoring of the late effects of new therapies (Gotay, 2004). Information about late effects would be much easier to obtain if patients agreed to long-term follow-up and monitoring when they entered a treatment trial and if investigators maintained current contact information as part of the treatment protocol.

Accruing Large and Heterogeneous Study Cohorts Through Multiple Institutions

Another inherent challenge for survivorship investigation is the need to study large numbers of individuals who will survive their cancers for many years. Study sample sizes must also be large enough to include individuals who will manifest unusual late effects and individuals who may have been exposed to unique treatments. In addition, the ability to detect interactions of cancer treatments with underlying comorbid conditions depends on studies with large and heterogeneous populations. Inclusion of individuals from ethnic minorities and medically underserved groups is also needed to identify health disparities and interventions to reduce them (Aziz and Rowland, 2002).

One mechanism to accrue large numbers of cancer survivors who represent the diversity of the United States is to conduct multi-institution collaborative research. Such efforts, while advantageous in terms of study design, can be costly and hard to administer. An area of particular concern is the process of gaining institutional review board (IRB) approval for research studies. In one study of IRB processes in a multisite mailed survey, investigators found that IRBs had different requirements that affected the consistency of project protocols (e.g., agreement on centralized data collection with outside firms; allowance for cash incentives for participation; requirement for active or passive physician consent before contacting subjects) (Greene and Geiger, 2004). Incorporating site-specific IRB requirements into project planning and potentially streamlining, centralizing, and reaching reciprocity agreements were recommended by investigators, especially for lower risk studies. Recognizing that IRBs are overloaded and underfunded, central or lead review boards have been recommended for multisite studies to reduce the redundancy of reviews and variability of approvals and/or required modifications to study design (IOM, 2003b).

Case Ascertainment Through Cancer Registries

Survivorship studies that enroll individuals identified through population-based cancer registries are advantageous because inferences from study results often can be generalized to the population at large. In contrast, results of studies based on convenience samples may be misleading because

of biases in selection (e.g., if only healthy survivors volunteer to be studied). A barrier to the timely conduct of cancer registry-based studies is the lack of rapid case ascertainment mechanisms to identify cases early enough to administer surveys or examinations within one year of diagnosis. Registries are an attractive means of identifying subjects for research but, in some areas, registries restrict access to individuals in the registry because of their involvement in other research studies. Shortages of resources and staff within the registries further hamper the conduct of research. Additional support for population-based cancer registries would not only improve their primary epidemiologic function, but would also improve survivorship research opportunities (IOM, 2000). With advances in information technology, it is likely that in the next decade cancer surveillance will be expanded to include quality of care measures and patient-centered outcomes (Hiatt, 2005).

Informed Consent

Adherence to legal requirements for human subject protection through informed consent can be labor intensive and contribute to problems in achieving high rates of participation among potential study subjects. As part of the ACS study of cancer survivors described above, investigators notified all physicians caring for potential study subjects of the study and obtained their consent to contact patients. In some states, investigators were able to inform physicians of the study and their plans to contact patients unless told not to do so. In contrast to this “passive consent” approach, other states required that physicians provide “active consent” in order to contact potential subjects. Physician restrictions on investigator access to patients, coupled with patient refusal to enter the study, resulted in participation rates that varied widely across the 14 states involved in the study (from 20 to 60 percent). The relatively low participation rates have led to concerns about the representativeness of the enrolled cohort of cancer survivors (Yates, 2004).

Assuring Privacy of Medical Records

Another potential barrier to the conduct of clinical and health services research has emerged with the passage of privacy provisions of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA).5 Under HIPAA, a federal Privacy Rule established new responsibilities for health

care providers, health plans, and other entities to protect the confidentiality of an individual’s health information (Box 7-4). Compliance with provisions of the Act was required by April 2003. Many investigators have subsequently concluded that HIPAA is having a deleterious impact on the conduct of clinical, epidemiologic, and health services research (Hiatt, 2003; Gunn et al., 2004; GAO, 2004; Raghavan, 2005).

HIPAA’s Privacy Rule has fundamentally changed the way researchers obtain health data (Gunn et al., 2004). Researchers must use one of three options to gain access to protected health information: obtain patient authorization; obtain a waiver of authorization by having their research protocol reviewed and approved by an IRB or privacy board; or use a limited dataset with direct identifiers removed. Researchers may seek health information without authorization if the data do not identify an individual and there is no reasonable basis to believe it could be used to identify an individual.

An ad hoc subcommittee of the National Cancer Advisory Board (NCAB) solicited comments from NCI-affiliated comprehensive and clinical cancer centers, cooperative groups, and Specialized Programs of Research Excellence (SPOREs) to assess the impact of HIPAA on oncology clinical research (Ramirez and Niederhuber, 2003; NCAB, 2003). The Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) has also solicited information on research activities that have been affected by the new HIPAA privacy regulations (AAMC, 2004). Consistent findings on HIPAA’s impact from the AAMC and NCAB surveys emerged (Ehringhaus, 2004):

-

The informed consent process is negatively affected (e.g., subjects are overwhelmed/confused by added length to consent form).

-

Recruitment is impaired or prevented (e.g., obtaining information from other providers has become more difficult).

-

Subject selection bias is introduced (e.g., complexity of the authorization form intimidates some potential participants, introducing potential biases).

-

Research processes are hindered (e.g., there is a burden of documentation, paperwork).

-

Research costs are increased (e.g., study resources are diverted to compliance).

-

Shifts in the direction of research are required (e.g., there are delays in gaining access to data, and some data are inaccessible).

-

Difficulties arise in collaborations (e.g., some providers no longer provide data; it is difficult to get agreement in multisite trials).

-

There are inconsistent interpretations of HIPAA requirements.

|

BOX 7-4 What Does HIPAA’s Privacy Rule Address? The Privacy Rule addresses the use and disclosure of individuals’ health information and establishes individuals’ rights to obtain and control access to this information. Specifically, the rule covers “protected health information,” defined as individually identifiable health information that is transmitted or maintained in any form. It applies to “covered entities,” defined as health plans, health care clearinghouses, and health care providers that transmit information electronically with respect to certain transactions. The protections under the Privacy Rule do not preempt state privacy laws that are more stringent. What Are Permissible Uses and Disclosures of Health Information Under HIPAA? Under the Privacy Rule, a covered entity may use and disclose an individual’s protected health information without obtaining the individual’s authorization when the information is used for treatment, payment, or health care operations. Protected health information may also be disclosed without an individual’s authorization for such purposes as certain public health and law enforcement activities, and judicial and administrative proceedings, provided certain conditions are met. In addition, an individual’s authorization is not required for disclosures for research purposes if a waiver of authorization, under defined criteria, is obtained from an institutional review board (IRB) or a privacy board.1 Except where the rule specifically allows or requires a use of disclosure without an authorization, the individual’s written authorization must be obtained. The Privacy Rule allows covered entities to use their discretion in deciding whether to disclose protected health information for many types of disclosures, such as those to family and friends, public health authorities, and health researchers.2 What Individual Privacy Rights Does the Privacy Rule Confer? The Privacy Rule provides the following:

|

The AAMC and NCAB have recommended that certain provisions of the Privacy Rule be amended to reverse these unintended consequences to medical research. Specifically, these groups recommend that some of the accounting of disclosure requirements be eliminated, that authorization and waiver processes be refashioned, and that standards for deidentification of records be relaxed (Ramirez and Niederhuber, 2003; Ehringhaus, 2004).

In summary, survivorship research has inherent challenges that include the difficulties and costs of following research subjects for lengthy periods and the need for large and diverse study populations. Additional challenges, not unique to survivorship research but which impact its conduct, are

administrative complexities associated with multi-institutional research and emerging problems associated with the implementation of the privacy provisions of HIPAA.

STATUS OF SURVIVORSHIP RESEARCH

The committee, in an effort to understand how resources for research are applied to questions regarding cancer survivorship, undertook a review of topics of investigation and levels of research spending. Such a review provides only a snapshot as of 2005, but it does give an indication of the

prominence and priority of survivorship within the field of cancer research, and a sense of the emphasis on different areas within cancer survivorship research. This assessment aided the committee as they considered ways in which a research program could be structured in the future to better respond to the needs of cancer survivors. There is no one comprehensive source of information on research support and, as part of its review, the committee relied on the following sources:

-

Descriptions of NIH-sponsored survivorship research compiled by the NCI’s Office of Cancer Survivorship

-

Listings of research projects in the CRISP (Computer Retrieval of Information on Scientific Projects), a searchable database of federally funded biomedical research projects conducted at universities, hospitals, and other research institutions6

-

Contacts with organization representatives (e.g., ACS, Lance Armstrong Foundation, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC])

-

Review of each organization’s website.

The committee’s review of research support is limited to federal agencies, primarily the National Institutes of Health and selected private organizations and foundations (i.e., ACS, Lance Armstrong Foundation, Susan G. Komen Foundation). Although these organizations are not the only sponsors of research on cancer survivorship, they represent the major funding sources for such research. Excluded from this review was research supported by health plans, insurers, pharmaceutical companies, and other private organizations. Much of the research done in those settings is proprietary.

Federal Research Support

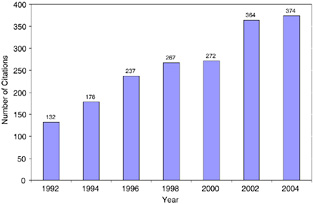

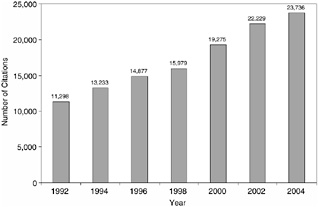

The level of dedicated NIH support for cancer survivorship research has grown from $2 to $22 million from 1998 to 2004, signaling a growing

|

6 |

CRISP is a biomedical database system containing information on research projects and programs supported by the Department of Health and Human Services. Most of the research falls within the broad category of extramural projects, grants, contracts, and cooperative agreements conducted primarily by universities, hospitals, and other research institutions, and funded by NIH and other government agencies (e.g., Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Food and Drug Administration, Health Resources and Services Administration, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality). CRISP also contains information on the intramural programs of NIH and Food and Drug Administration (NIH, 2004a). |

interest in the area (Figures 7-3 and 7-4).7 While the increase in support has been substantial, survivorship research support represents a tiny fraction of support for treatment-related research, estimated at more than $1 billion in 2003 (NCI, 2003a). Cancer survivorship research is conducted throughout the institutes of NIH (e.g., National Institute on Aging, National Institute of Nursing Research, National Institute of Mental Health, National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine). Within the NCI, several Divisions have ongoing survivorship-related activities (e.g., Division of Cancer Prevention, Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences, Division of Cancer Treatment and Diagnosis, and the Training Branch). The locus of cancer survivorship research at the federal level is the NCI’s Office of Cancer Survivorship.

National Cancer Institute, Office of Cancer Survivorship

The NCI’s Office of Cancer Survivorship was established in 1996 to support research on the physical, psychosocial, and economic consequences of cancer among survivors (of all ages), their families, and caregivers (NCI, undated). The Office of Cancer Survivorship supports research related to:

-

The identification, prevention, and amelioration of the late effects of cancer and its treatment;

-

Follow-up care and surveillance of cancer survivors and their family members;

-

Optimization of health after cancer treatment; and

-

Communication to health care professionals, cancer survivors and their families, and the public regarding survivorship issues.

The Office of Cancer Survivorship has led a modest level of survivorship-specific grant initiatives since its inception, and has been successful in efforts to incorporate consideration of survivorship issues into diverse NCI-supported funding mechanisms (e.g., program announcements

|

7 |

For these estimates, survivorship research was defined as that which focused on the health and life of a person with a history of cancer beyond the acute diagnosis and treatment phase. Studies that examined newly diagnosed survivors or those in active treatment were included in the estimates if follow-up lasted at least 2 months or longer post-treatment. Studies addressing recurrence or end-of-life research were not included in these estimates. Estimates include research conducted among survivors of both childhood and adult cancers (NCI, 2005b). These estimates of dedicated NIH support for cancer survivorship do not capture all survivorship research, for example, that conducted through the Clinical Trials Cooperative Groups Program. |

for R03 and R21 applications),8 as well as several trans-NIH program initiatives. In terms of its own research portfolio, the Office of Cancer Survivorship awarded its first formally solicited research grants in 1997, totaling $4 million over 2 years (NCI, 1998). In 1998, the Office of Cancer Suvivorship awarded another $15 million over 5 years in response to its Long-Term Cancer Survivors Request for Applications (RFA). The Office of Cancer Survivorship awarded $1 million in 2000 to support supplements to comprehensive cancer centers (P30s) to conduct pilot or exploratory research on issues related to the functioning of family members of survivors. In 2001, using a similar mechanism, the Office of Cancer Survivorship awarded an additional $1 million to support pilot research on issues faced by minority and underserved cancer survivors. A reissuance of the original Long-Term Cancer Survivors RFA was announced in 2003 and 17 new grants were awarded9 with $6 million over 5 years (with co-funding from the CDC and the National Institute on Aging) (Aziz, 2002, 2004; Rowland, 2004). Over its lifetime, the Office of Cancer Survivorship has controlled and distributed about $28 million to support cancer survivorship research. With limited resources of its own, the Office of Cancer Survivorship has actively encouraged investigators to utilize a number of existing support mechanisms that are relevant to cancer survivorship research (Box 7-5).

Health services research has been a somewhat less well-developed area of survivorship research. Two new NCI-supported research initiatives will provide much needed information about late effects among, and the care received by, cancer survivors (Aziz, 2004):

-

Follow-up Care Use by Survivors (FOCUS)—This population-based study of 1,600 survivors of breast, prostate, colorectal, and gynecologic cancer will examine the self-reported prevalence of long-term and late effects of cancer treatment, aspects of follow-up care (frequency, content, setting, experiences, and perceived quality and purpose), knowledge of late effects of cancer treatment, screening and health behaviors, and attitudes toward and practices regarding cancer follow-up care.

-

Experiences of Care and Health Outcomes Among Survivors of NHL (ECHOS-NHL)—The quality of follow-up care provided to adult survivors of aggressive non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma will be assessed along with related health outcomes.

|

BOX 7-5

SOURCES: NIH (2004b,c). |

A physician survey to learn more about cancer control practices is planned in 2006–2007. Questions will be included to ascertain physicians’ follow-up care recommendations and practices for cancer survivors (Personal communication, J. Rowland, Office of Cancer Survivorship, NCI, April 12, 2005).

An important opportunity to disseminate research findings is provided by a biennial conference on cancer survivorship co-sponsored by the NCI and the ACS. The meeting also provides a forum for interdisciplinary dialogue, sessions for professional education and training, and networking opportunities for new investigators (NCI and ACS, 2004).

Department of Defense (DoD)

Beginning in FY 1992, the U.S. Congress directed DoD to manage several appropriations for an extramural grant program directed toward specific research initiatives. The U.S. Army Medical Research and Materiel Command established the office of the Congressionally Directed Medical

Research Programs (CDMRP) to administer these funds. Between FY 1992 and 2004, $1.65 billion has been appropriated by Congress to DoD for research on breast cancer (DoD, 2004a). In addition, $10.3 million has been generated in sales of the U.S. Postal Service’s first-class stamp (Pub. L. No. 105–41, Stamp Out Breast Cancer Act [H.R. 1585]). Since 1997, Congress has appropriated money to fund peer-reviewed research for prostate cancer ($565 million appropriated to date), ovarian cancer ($81 million), and chronic myelogenous leukemia ($13.5 million). The CDMRP attempts to identify gaps in funding and provide award opportunities that will enhance program research objectives without duplicating existing funding opportunities. A number of funded research projects are related to cancer survivorship, including those focused on quality of life and symptom management (DoD, 2004b). Training grants are available through CDMRP and have include those related to psycho-oncology.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality

AHRQ has published evidence reports on the management of cancer symptoms (i.e., pain, depression, and fatigue) and the effectiveness of behavioral interventions to modify physical activity behaviors in cancer patients and survivors (AHRQ, 2002b, 2004a). Additional syntheses related to survivorship may be forthcoming because cancer is among the 10 top conditions affecting Medicare beneficiaries and therefore, the subject of a new AHRQ initiative. State-of-the art information about the effectiveness of interventions for these conditions will be developed, including reviews of prescription drugs. Funding for the initiative was authorized by the Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act of 2003. Systematic reviews and syntheses of the scientific literature will focus on the evidence of outcomes, comparative clinical effectiveness, and appropriateness of health care items such as pharmaceuticals and health care services, including the manner in which they are organized, managed, and delivered (AHRQ, 2004b).

Two large research networks supported by AHRQ could provide opportunities for survivorship research. The Primary Care Practice-based Research Networks (PBRNs) provide opportunities to examine care within primary care settings. Together, the 19 PBRNs provide access to more than 5,000 primary care providers and nearly 7 million patients across the United States (AHRQ, 2001). Among the research that has been conducted within PBRNs is a study of the coordination between referring physicians and specialists (Forrest et al., 2000). The Integrated Delivery System Research Network (IDSRN) is a model of field-based research that links researchers with large health care systems to conduct research (AHRQ, 2002a). As a group, the IDSRN provides health services in a wide variety of organiza-

tional care settings to more than 55 million Americans. IDSRN partners collect and maintain administrative, claims, encounter, and other data on large populations that are clinically, demographically, and geographically diverse. From 2000 to 2004, AHRQ has provided nearly $20 million for 75 projects. One of these projects is analyzing ways to improve communication and care monitoring among providers collaborating on care within different care settings. The PBRN and IDSRN have not yet been used to investigate survivorship issues directly, but both networks could be valuable resources for such research.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

The CDC has recognized cancer survivorship as one of the many chronic conditions for which a public health approach is needed. Evaluation of survivorship services and research on preventive interventions were among the recommendations in the report co-sponsored by CDC and the Lance Armstrong Foundation, A National Action Plan for Cancer Survivorship: Advancing Public Health Strategies. To further this report’s recommendations, the CDC has supported state efforts to develop comprehensive cancer control plans that incorporate initiatives to meet the needs of cancer survivors (see Chapter 4). The CDC oversees the National Program of Cancer Registries (NPCR) and is supporting a study in New York state to assess the feasibility of using existing data sources to collect the follow-up data needed for basic survival analysis in a statewide cancer registry. Another study will measure and explore differences in cancer survival among cancer patients in Europe, Canada, and the United States (CONCORD Study) (CDC, 2003). CDC is in the process of developing an agencywide research agenda that will include a focus on public health interventions to further reduce the risk factors associated with the leading causes of death and illness, including heart disease, cancer, and diabetes (CDC, 2005).

Private Research Support

Private philanthropic organizations have been major sponsors of cancer research. This section of the report reviews the research activity of two national sponsors of survivorship-related research on all types of cancer, the ACS and the Lance Armstrong Foundation, and a foundation that supports research related to breast cancer.10

American Cancer Society

The ACS is the largest nongovernmental source of cancer research funding in the United States and supports psychosocial and behavioral research. In FY 2003–2004, approximately 17 percent of the total research program was devoted to these areas. The Society’s intramural research program includes a Behavioral Research Center, which is conducting two large population-based surveys of cancer survivors (described above). The ACS Behavioral Research Center is also analyzing data on health-related quality of life of cancer survivors who are Medicare beneficiaries enrolled in managed care plans. The data are from the Medicare Beneficiary Survey, a national survey conducted for the Department of Health and Human Services’ Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Survivorship-related grants that are active through ACS’s extramural program are shown in Box 7-6. The total level of support for these grants is approximately $4 million.

Lance Armstrong Foundation (LAF)

The mission of the Lance Armstrong Foundation is to enhance the length and quality of life of those living with, through, and beyond cancer with activities targeted to cancer survivorship. LAF was founded in 1997 by cancer survivor and champion cyclist Lance Armstrong. By 2005, LAF had awarded more than $9.7 million for 75 grants on the study of testicular cancer and survivorship issues (LAF, 2004, 2005). Survivorship-related awards in 2003 include those related to the effects of physical activity on relieving chronic fatigue and other late effects, educational interventions to reduce breast cancer among Hodgkin’s disease survivors, and long-term follow-up of survivors of Hodgkin’s lymphoma enrolled in trials conducted by the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Lymphoma Group (LAF, 2004). Awards made in 2004 include those to study follow-up care for African-American breast cancer survivors, the impact of exercise in lymphoma survivors, and the fertility of women following chemotherapy for early breast cancer. Other initiatives will focus on chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy and the psychological late effects of cancer (LAF, 2005).

LAF has received support from CDC to disseminate programs to improve cancer survivorship among African Americans, American Indians, Alaskan Natives, Spanish speakers, and rural Americans. LAF plans to develop and disseminate culturally relevant and linguistically appropriate materials for these groups (CDC, 2004).

|

BOX 7-6

SOURCE: Personal communication, B. Teschendorf, ACS, February 23, 2005. |

Susan G. Komen Foundation

The Susan G. Komen Foundation is dedicated to eradicating breast cancer through research and education. Since its inception in 1982, it has awarded over $144 million through more than 1,000 research grants. In 2003–2004, the Foundation supported five survivorship-related research grants totaling approximately $1.25 million (Komen Foundation, 2004). The projects supported by the grants explore topics such as memory problems, osteoporosis, and other long-term treatment effects; characteristics and needs of Hispanic breast cancer survivors; and outcomes in women diagnosed with breast cancer during pregnancy.

Summary

Federal investments in cancer survivorship research have been relatively modest. The NCI’s Office of Cancer Survivorship, the federal locus

for cancer survivorship research, has distributed an estimated $28 million in research funds to date. The Office of Cancer Survivorship oversees a small grant portfolio and leverages resources from other parts of NIH to encourage survivorship research. Additional support for clinical survivorship research has been available through the NCI’s Clinical Trials Cooperative Group Program, but the level of such support, while difficult to gauge, appears to be low. These groups represent important opportunities to evaluate the consequences of contemporary cancer treatments. CDC’s new focus on survivorship and public health and AHRQ’s focus on cancer among Medicare beneficiaries could lead to increased research support related to cancer survivorship. Other federal support is available for survivorship research through the DoD’s extramural grant programs. In terms of private resources for research, the ACS has invested in large survivorship cohort studies; the Lance Armstrong Foundation is building on its portfolio of survivorship research; and other private foundations are supporting research on survivorship issues relevant to their constituencies.

FINDINGS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

In summary, cancer survivorship research has emerged as a unique area of inquiry covering areas such as clinical late effects, psychosocial adjustment, and quality of care. The field is by nature interdisciplinary and includes investigators in nursing, clinical medicine, epidemiology, and health services research. Within the past decade, a focus for federally sponsored research has been organized within the NCI. Findings from this research have informed much of this report. Investigators have used several mechanisms to conduct survivorship research, including focus groups and other qualitative methods, clinical trials, cohort studies, cancer registries, administrative data, and surveys. Among the challenges to conducting survivorship research are the difficulties and costs associated with long-term follow-up, the complexities of accruing sufficient sample sizes through multi-institutional research endeavors, changes in treatment and the latency to recognition of late effects, and emerging problems associated with compliance with HIPAA. Survivorship research is funded at relatively modest levels within both public and private sectors, especially as contrasted to levels of support for treatment-related research.

Recommendation 10: The National Cancer Institute (NCI), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), private voluntary organizations such as the American Cancer Society (ACS), and private

health insurers and plans should increase their support of survivorship research and expand mechanisms for its conduct. New research initiatives focused on cancer patient follow-up are urgently needed to guide effective survivorship care.

Research is especially needed to improve understanding of:

-

Mechanisms of late effects experienced by cancer survivors

-

How to identify and intervene to alleviate symptoms and improve function

-

The prevalence and risk of late effects (prospective, long-term follow-up studies are needed)

-

The cost-effectiveness of alternative models of survivorship care and community-based psychosocial services

-

Post-treatment surveillance strategies and interventions (large clinical trials are needed)

-

Survivors’ and caregivers’ attitudes and preferences regarding outcomes and survivorship care

-

Needs of racial/ethnic groups, residents of rural areas, and other potentially underserved groups

-

Supportive care and rehabilitation programs

-

-

Interventions to improve quality of life

-

Family and caregiver needs and access to supportive services

-

Mechanisms to reduce financial burdens of survivorship care (e.g., the new Medicare prescription drug benefit should be carefully monitored to evaluate its impact, especially how private plan formularies cover cancer drugs)

-

Employer programs to meet return-to-work needs

-

Approaches to improve health insurance coverage

-

Legal protections afforded cancer survivors through the Americans with Disabilities Act, Family and Medical Leave Act, HIPAA, and other laws

-

-

Survivorship research methods

-

Barriers to participation

-

Impact of HIPAA

-

Methods to overcome challenges of survivorship research (e.g., methods to adjust for bias introduced by nonparticipation; methods to minimize loss to follow-up)

-

To conduct research in these priority areas, large study populations are needed that represent the diversity of cancer survivors in terms of their type of cancer and treatment as well as their sociodemographic and health care characteristics. Existing research mechanisms need to be fully utilized and expanded to provide opportunities for cancer survivorship research:

NCI Cooperative Groups—More long-term follow-up studies need to be conducted of individuals enrolled in clinical trials.

SPOREs (P50) or Research Program Projects (P01)—Extramural research mechanisms could be used to support focused research efforts on survivorship. Such mechanisms facilitate interdisciplinary collaboration and take advantage of services and infrastructure available through core institutional support.

NCI-sponsored special studies—Additional survivorship special studies are needed that are based on population-based cancer registries.

National surveys—Refinements to ongoing national surveys (e.g., the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey) and supplements to others (e.g., National Health Interview Survey) could help capture information on survivorship.

Population-based cancer registries—The SEER Program and the NPCR should begin to collect data on cancer recurrence among survivors as an outcome measure. State and regional registries should also develop mechanisms to obtain comorbidity data that can be used to enhance analyses of short-term and long-term outcomes among cancer survivors. Measures of socioeconomic status (e.g., income, education, health insurance status) would assist health services researchers as they assess health care disparities in cancer care and outcomes. These additional data and measures could be obtained through existing linkages with Medicare claims in the SEER-Medicare database, new linkages with electronic data from health plans and provider networks, or an expansion of data elements that are routinely reported by hospitals and physicians to cancer registries. Opportunities should be sought to link data from cancer registries to other administrative databases (e.g., private insurance claims, Medicaid data).

Health services research resources—The follow-up period of ongoing cancer health services research studies (e.g., CanCORS) should be extended to yield more information on long-term survivorship.

Research networks—Investigators should be encouraged to use existing research networks (e.g., CRN, PBRN, IDSRN) to conduct cancer survivorship research.

Longitudinal studies—Longitudinal studies such as the Nurses’ Health Study and the Physician’s Health Study provide opportunities to assess survivorship issues.

In addition to harnessing these existing mechanisms, the committee recommends that federal and private research sponsors support a large new research initiative on cancer patient follow-up. Answers to the following basic questions about survivorship care are needed: How frequently should patients be evaluated following their primary cancer therapy? What tests

should be included in the follow-up regimen? Who should provide follow-up care? A call for such research was made in the Institute of Medicine’s 1999 Ensuring Quality Cancer Care report, but it has not yet been conducted (IOM, 1999). In some cases large clinical trials will be needed to answer these questions. There is renewed interest in designing affordable and relatively simple practical trials, registries, and other real-world prospective studies to answer the many such clinical questions (Tunis, 2005).

During follow-up, the ability to detect cancer recurrence and late effects is usually of great concern to survivors and providers alike. The modalities used for detection are numerous and may be very costly. Cancer patient follow-up typically lasts indefinitely or at least for many years after primary therapy. There is significant and sometimes dramatic variation in follow-up practices (see Chapter 4) and associated costs (Johnson and Virgo, 1997). Much of this variability is currently felt to stem from a lack of high-quality evidence supporting any particular strategy. Gathering such evidence by means of well-designed clinical trials of alternative follow-up strategies is expensive, in part because such trials must incorporate many years of surveillance.

The committee concludes that improvements in cancer survivors’ care and quality of life depend on a much expanded research effort.

REFERENCES

AAMC (American Association of Medical Colleges). 2004. Welcome to the AAMC Project to Monitor and Document the Effects of HIPAA on Research. [Online]. Available: http://services.aamc.org/easurvey/survey/login.cfm [accessed December 9, 2004].

ACoS (American College of Surgeons). 2004. What is the NCDB? [Online]. Available: http://www.facs.org/cancer/ncdb/ncdbabout.html [accessed February 23, 2005].

AHRQ (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality). 2001. Primary Care Practice-based Research Networks. Rockville, MD: AHRQ.

AHRQ. 2002a. Integrated Delivery System Research Network (IDSRN): Field Partnerships to Conduct and Use Research. Fact Sheet. AHRQ Publication No. 03-P00. [Online]. Available: http://www.ahrq.gov/research/idsrn.htm [accessed April 1, 2005].

AHRQ. 2002b. Management of Cancer Symptoms: Pain, Depression, and Fatigue. Summary, Evidence Report/Technology Assessment: Number 61. AHRQ Publication No. 02-E031. [Online]. Available: http://www.ahrq.gov/clinic/epcsums/csympsum.htm [accessed December 21, 2004].

AHRQ. 2004a. Effectiveness of Behavioral Interventions to Modify Physical Activity Behaviors in General Populations and Cancer Patients and Survivors. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment 102. Rockville, MD: AHRQ.

AHRQ. 2004b. List of Priority Conditions for Research under Medicare Modernization Act Released. Press Release. [Online]. Available: http://www.ahrq.gov/news/press/pr2004/mmapr.htm [accessed December 17, 2004].

Arredondo SA, Downs TM, Lubeck DP, Pasta DJ, Silva SJ, Wallace KL, Carroll PR. 2004. Watchful waiting and health related quality of life for patients with localized prostate cancer: Data from CaPSURE. J Urol 172(5 Pt 1):1830–1834.

Ayanian JZ, Chrischilles EA, Fletcher RH, Fouad MN, Harrington DP, Kahn KL, Kiefe CI, Lipscomb J, Malin JL, Potosky AL, Provenzale DT, Sandler RS, van Ryn M, Wallace RB, Weeks JC, West DW. 2004. Understanding cancer treatment and outcomes: The Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance Consortium. J Clin Oncol 22(15):2992–2996.

Aziz N. 2004 (July 26–27). The Art and Science of Cancer Survivorship in the New Millennium: An Integral Concept Underlying Quality Care. Presentation at the Meeting of the IOM Committee on Cancer Survivorship, Woods Hole, MA.

Aziz NM. 2002. Cancer survivorship research: Challenge and opportunity. J Nutr 132(11 Suppl):3494S–3503S.

Aziz NM, Rowland JH. 2002. Cancer survivorship research among ethnic minority and medically underserved groups. Oncol Nurs Forum 29(5):789–801.

Aziz NM, Rowland JH. 2003. Trends and advances in cancer survivorship research: Challenge and opportunity. Semin Radiat Oncol 13(3):248–266.

Barzilai DA, Cooper KD, Neuhauser D, Rimm AA, Cooper GS. 2004. Geographic and patient variation in receipt of surveillance procedures after local excision of cutaneous melanoma. J Invest Dermatol 122(2):246–255.

Begg CB, Riedel ER, Bach PB, Kattan MW, Schrag D, Warren JL, Scardino PT. 2002. Variations in morbidity after radical prostatectomy. N Engl J Med 346(15):1138–1144.

Bergmann MM, Byers T, Freedman DS, Mokdad A. 1998. Validity of self-reported diagnoses leading to hospitalization: A comparison of self-reports with hospital records in a prospective study of American adults. Am J Epidemiol 147(10):969–977.

Bernhard J, Cella DF, Coates AS, Fallowfield L, Ganz PA, Moinpour CM, Mosconi P, Osoba D, Simes J, Hurny C. 1998. Missing quality of life data in cancer clinical trials: Serious problems and challenges. Stat Med 17(5–7):517–532.

Bradley CJ, Given CW, Roberts C. 2003. Late stage cancers in a Medicaid-insured population. Med Care 41(6):722–728.

Brown ML, Riley GF, Potosky AL, Etzioni RD. 1999. Obtaining long-term disease specific costs of care: Application to Medicare enrollees diagnosed with colorectal cancer. Med Care 37(12):1249–1259.

Buchanan DR, O’Mara AM, Kelaghan JW, Minasian LM. 2005. Quality-of-life assessment in the symptom management trials of the National Cancer Institute-supported community clinical oncology program. J Clin Oncol 23(3):591–598.

Butterfield RM, Park ER, Puleo E, Mertens A, Gritz ER, Li FP, Emmons K. 2004. Multiple risk behaviors among smokers in the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study cohort. Psychooncology 13(9):619–629.

CaPSURE. 2005a. Publications. [Online]. Available: http://www.capsure.net/pub/pub.aspx [accessed January 24, 2005].

CaPSURE. 2005b. What is CaPSURE? [Online]. Available: http://www.capsure.net [accessed January 19, 2005].

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2003. Science in Brief: Cancer Registries. National Program of Cancer Registries Research and Evaluation Activities. Atlanta, GA: CDC.

CDC. 2004. Lance Armstrong Foundation. [Online]. Available: http://www.cdc.gov/cancer/partners/fp_laf.htm [accessed March 17, 2004].