8

Using Marketplace Incentives to Leverage Needed Change

Summary

The previous chapters identify areas in which change is needed on the part of federal and state governments, health care organizations, and individual clinicians, among others. The feasibility of many of these changes depends on how accommodating the marketplace is to them, particularly with respect to the ways in which purchasers of mental and/or substance-use (M/SU) health care exercise their marketplace roles.

The M/SU health care marketplace has some unique features that distinguish it from the general health care marketplace. These include the dominance of government (state and local) purchasers, the frequent purchase of insurance for M/SU health care separately from that for other health care (i.e., the use of “carve-out” arrangements), the tendency of the private insurance marketplace to avoid covering or to offer more-limited coverage to individuals with M/SU illnesses, and government purchasers’ greater use of direct provision and purchase of care rather than insurance arrangements. Attending to these differences is essential if the marketplace is to promote quality improvement in M/SU health care. The committee recommends four ways of strengthening the marketplace to this end.

KEY FEATURES OF THE MARKETPLACE FOR MENTAL AND SUBSTANCE-USE HEALTH CARE

People with mental and/or substance-use (M/SU) problems and illnesses receive care from a range of provider organizations and individual clinicians—most often from private providers operating in market settings. However, while the majority of individuals have their general and mental health care paid for by private insurance, most payments for M/SU treatments are made by government, either in the form of payments from public insurance (Medicare and Medicaid) or through states’ direct purchase of services from providers. This section reviews the key features of the marketplace for M/SU health care that distinguish it from that for other types of care.

Dominance of Government Purchasing

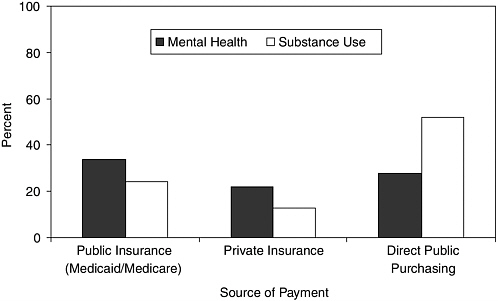

Recent estimates suggest that payment for roughly 63 percent of mental health care and 76 percent of substance-use treatment is made by public sources (Mark et al., 2005). Figure 8-1 shows the distribution of spending for M/SU care by major sources of payment as of 2001. In the case of mental health care, the majority (54 percent) of all public spending (direct public purchasing and public insurance) makes use of health insurance

FIGURE 8-1 Financing methods for mental health/substance-use care in 2001.

SOURCE: Mark et al., 2005.

mechanisms; public health insurance consists primarily of the Medicaid and Medicare programs. For substance-use treatment, a larger majority (68 percent) of spending is on direct government grants and contracts with providers. The implication is that payments for substance-use services are most frequently allocated outside of markets. When private spending is also considered, approximately 56 percent of all payments for mental health care are made through insurance mechanisms, as opposed to out-of-pocket payments, grants, donations, and other sources of private financing. In contrast, only 27 percent of private payments for substance-use treatment flows through insurance arrangements. Again, this suggests a somewhat lesser impact of insurance market failure on substance-use care.

The implication of these figures is that choices about the level and composition of spending on M/SU health care are affected by a mix of market and political forces and that these forces differ for health care for mental and substance-use conditions. The willingness to pay for treatment for M/SU problems and illnesses is expressed through private markets for health insurance; political decisions about the design of public insurance; and the categorical program budgets of federal, state, and local agencies charged with providing such treatment.

Purchase of M/SU Health Insurance Separately from General Health Insurance

Insurance for M/SU health care is governed by a distinctive set of arrangements. Although the proportion has been declining in recent years, most Americans (64 percent in 2002) under the age of 65 continue to receive health care through insurance provided by either their own employer or that of a family member (Fronstin, 2003). The terms under which individuals choose insurance and under which health plans compete to provide it are defined by organizations that purchase the insurance in the marketplace. Employers, state governments as administrators of Medicaid programs, and the federal government through the Medicare program all define the rules under which markets for health insurance operate.

Larger employers allow employees and their dependents to choose among a number of insurers and products (e.g., preferred provider organization, health maintenance organization) in competitive insurance markets. Smaller employers frequently offer only a single insurance plan to their employees. Some large employers focus special attention on M/SU coverage and spending. In these cases, employers separate the insurance risk for M/SU treatment from that for other health insurance, and create what have become known as managed behavioral health care organization (MBHO) carve-out contracts (Frank and McGuire, 2000). Under such circumstances, an employee has no choice of coverage for M/SU health care since the

benefit is managed by a single organization, regardless of the options available for general health care. Approximately 20 percent of privately insured people are covered under such a carve-out arrangement. For most of the remaining 80 percent, their private general health plan enters into a subcontract with a carve-out MBHO to manage its M/SU care benefit. In this case, employees and their dependents can choose among both general and M/SU health care benefits across a set of health plans. Finally, some health plans offer M/SU coverage that is integrated with the rest of the health insurance risk; such plans represent a modest share of the private market.

Medicaid, the federal–state government program that focuses on the poor and disabled, includes managed care arrangements and insurance that follows the principles of fee-for-service–indemnity health insurance. Under Medicaid managed care, the use of MBHO carve-outs mirrors the approach taken by private insurance. Roughly 16 states have direct payer carve-out contracts with MBHOs (CMS, 2004). Most Medicaid managed care plans not operating in environments where the Medicaid program has a direct carve-out have subcontracts with carve-out vendors.

More Limited Insurance Coverage

While nearly all private insurance plans offer some coverage for treatment of M/SU illnesses, the coverage is often substantially more limited than that for other medical conditions (Barry et al., 2003). In 2002, 96 percent of people with employer-based coverage had inpatient M/SU coverage, and 98 percent had outpatient coverage; these figures represent a small increase over the proportion of insured covered for these treatments in 1991. M/SU services are typically subject to limits on the number of annual reimbursable outpatient visits and inpatient days. Approximately 74 percent of covered employees have limits on outpatient visits and 65 percent limits on inpatient days.

The fee-for-service component of Medicaid pays for a range of mental health services. Because there is little reliance on consumer cost sharing, however, rationing of supply is common. This is a side effect of below-market payment rates for providers, especially providers of ambulatory care. The result is low participation rates in Medicaid among office-based clinicians, such as psychiatrists and psychologists. Coverage for substance-use care under Medicaid is considerably more limited than that for mental health services (McCarty et al., 1999). Inpatient care for mental illnesses in adults under the age of 65 is limited to general hospitals under the so-called Institutions for Mental Disease (IMD) exclusion provisions of the original enabling Medicaid legislation. Thus the breadth of providers available is limited to a subset of those that supply inpatient psychiatric and substance-use treatment (for a detailed discussion and history of the IMD provisions, see HCFA, 1992).

Medicare offers a fee-for-service indemnity insurance type of benefit. A small portion (about 14 percent) of Medicare beneficiaries are enrolled in managed care plans that contract with the Medicare program to offer services to Medicare beneficiaries (CMS, 2005). Traditional Medicare (the indemnity component) covers M/SU care. Outpatient coverage carries relatively high cost sharing (50 percent), except for medication management (20 percent). Inpatient coverage is largely on the same basis as that for other medical conditions, with one exception: treatment in specialty psychiatric hospitals is limited to 190 days over an individual recipient’s lifetime. Also, psychiatric care is covered under a form of prospective payment that differs from the case-based diagnosis-related group (DRG) system used in Medicare generally.

Frequent Direct Provision and Purchase of Care by State and Local Governments

A unique feature of the structure of service delivery for M/SU health care is the large role assigned to public hospitals and clinics and to non–insurance-based purchase of services by state and local governments. In the United States, state and local governments directly deliver or purchase the bulk of M/SU services. Thus, financing relies on state and local tax revenues instead of individual consumer premiums or federal government funding, although the federal government plays a larger role in funding the direct purchase of substance-use treatment services through the federal block grants to states. Further, nearly all states operate under balanced-budget statutes. As a result, the political competition for funding of public services is intense. Funding for M/SU services is frequently pitted against that for roads, schools, and prisons in state budgeting processes. State and local governments pay for direct provision of M/SU services through networks of community-based providers that commonly serve a catchment area with a defined population. These community-based providers are most often private nonprofit organizations and are generally long-time incumbents in their service delivery role. Public M/SU services therefore resemble a monopoly arrangement whereby state and local governments grant a franchise to a nonprofit care provider agency.

Thus, the delivery of M/SU care in the United States is organized and financed through a patchwork of insurance and direct provision of services. In some cases, markets play a prominent role in resource allocation; in others, government and administrative practices are central in shaping what services are delivered and which people are served. In all cases, powerful institutions are involved in the purchase of the services. Understanding how these approaches to purchasing operate and what effects they have on the marketplace may help in identifying ways to facilitate improvements in the quality of care for people with M/SU problems and illnesses.

CHARACTERISTICS OF DIFFERENT PURCHASING STRATEGIES

M/SU health care delivery systems encompass a diverse array of purchasing arrangements, market structures, and government participation, each with differing effects on access to and the quality and cost of care.

Purchase Through Competitive Insurance Markets: Competition for Enrollees

One common approach to the purchase of insurance is for an employer or a state Medicaid program to select a group of health plans that will be permitted to compete for its enrollees. The payer first establishes a set of criteria that plans wishing to compete for its enrollees must meet. Such criteria typically address benefit design, performance, and cost. Programs that meet these criteria are then permitted to compete for enrollees, who are offered information on benefit structure and some quality indicators for each plan offered. In most cases, enrollees face premiums that are subsidized (zero in the case of Medicaid). In theory, payments made by the payer to the plan create incentives for efficient provision of services. Competition for enrollees should be less oriented toward price because of the subsidy and thus should promote consumer choice based on quality. The combination of capitation payments and quality competition among plans should lead to a reasonable balance between cost and quality.

However, competition for enrollees in the presence of risk-based premiums (e.g., capitation) also has some well-known drawbacks (Cutler and Zeckhauser, 2000; IOM, 1993). This type of purchasing creates financial incentives for health plans to adopt policies that discourage high-cost individuals from enrolling. These incentives also may result in uneven coverage across therapeutic areas and potentially uneven quality.

Ideally, health plans would ration care so that the incremental contributions to health of spending on each type of service (e.g., cancer care, heart disease treatment, and mental health) would be equal. This approach would guarantee the maximum level of health for a population given a fixed budget (as is implied by capitation payments). Under a fixed-payment arrangement, however, competitive health plans have incentives to depart from such an ideal allocation strategy. Specifically, since people with M/SU illnesses are more costly to insure and payments to health plans do not recognize those differences, plans have an incentive to avoid enrolling persons with such illnesses. An example comes from recent analyses of the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (Anderson and Knickman, 2001; Druss et al., 2001) showing that per capita health spending for people with mood disorders is more than four times that for individuals without such illnesses.

Incentives to avoid enrolling these people create a serious threat to quality of care through health insurance.

In insurance markets where M/SU services are part of the general risk pool, competition is reoriented to avoiding “bad risks.” One result is that plans limit coverage for conditions, such as M/SU illnesses, that attract high-cost enrollees. Low-cost individuals gravitate toward health plans offering limited insurance coverage at a lower premium, leaving the sickest enrollees in plans with relatively generous coverage. If premiums do not reflect differences in the enrolled population, plans offering more generous coverage will lose money; the result can be a so-called “death spiral” in coverage for treatment of M/SU illnesses. The Federal Employees Health Benefit Program (FEHBP) during the 1980s and 1990s offers an important case study of this phenomenon. In 1980, the FEHBP was viewed as model for mental health coverage; at that time, 7.8 percent of the program’s spending was devoted to treatment of mental illnesses. By 1997, the coverage offered had deteriorated to involve high levels of cost sharing and strict limits on inpatient days and outpatient visits. Observed spending on mental health as a share of total health spending had declined to 1.9 percent (Foote and Jones, 1999; Padgett et al., 1993).

Quality of care can be affected by the same market dynamics as those associated with selection incentives. In the era of managed care and its offshoots, those same competitive incentives can result in markets for health insurance supplying insufficient levels of service and quality of care for M/SU illnesses. The hallmark of the modern health plan is that a variety of new rationing mechanisms—including provider payment strategies, prior authorization programs, and the design of provider networks—are substituted for traditional demand-side cost-sharing features. Miller and Luft (1997:20) highlight this point:

Under the simple capitation payment arrangements that now exist, plans and providers face strong financial disincentives to excel in the care for the sickest and most expensive patients. Plans that develop a strong reputation for excellence in quality of care for the sickest will attract new higher-cost enrollees….

The implication is that health plans can use administrative mechanisms to compete to avoid “bad risks.” Rationing so as not to offer the best quality of M/SU health care in a market represents one method of trying to avoid a group of high-cost enrollees. Nothing in the modern market for health insurance has diminished the incentives to avoid enrolling high-cost individuals. Moreover, the evidence of market outcomes consistent with selection incentives for people with M/SU illnesses is strong (Cao, 2003; Cao and McGuire, 2003; Deb et al., 1996; Ellis, 1985; Frank et al., 2000; Normand et al., 2003).

There are two means by which a health plan can affect the intensity of rationing of M/SU health care when it (rather then the employer or other group purchaser) carves out behavioral health care: through the level at which it sets the carve-out health plan’s budget (via the capitation rate) and through the performance requirements specified in a contract. It is common to see capitation rates of $2.00 or less per member per month, a figure generally viewed as being consistent with a minimal level of care.

Direct Purchase of Carve-Out Services by Group Payers

A second prominent approach to purchasing insurance coverage for M/SU health care is for the payer to purchase carve-out services directly. This approach involves separating the risks associated with care for these illnesses from general health care risks and entering into specific contracts for coverage of M/SU care. Such direct purchase of carve-out services is used by approximately one-third of large employers (5,000 employees or more), 5 percent of midsized employers, and about 16 state Medicaid programs (Hodgkin et al., 2000; CMS, 2004). This method of purchasing removes M/SU health care from competition for enrollees, thereby attenuating the selection incentives concerning coverage and quality discussed above. However, use of such carve-out arrangements has implications for care coordination (see Chapter 5).

Direct purchase of carve-out M/SU services by group health care payers uses competition as the means of awarding contracts for these services. That is, a payer will frequently solicit proposals and bids from MBHO carve-out vendors to manage the M/SU health care for a defined population. The requests for proposals specify the areas of performance on which the contract will be awarded. The most common areas of performance are costs, responses of the utilization management system (e.g., speed of telephone response to member calls, speed of referral to a provider), and plan member satisfaction. There is, of course, considerable variation in the specifics, with some payers developing relatively elaborate measures of access and quality. However, the typical contract specifies few indicators of clinical quality, such as depression medication measures.

State Medicaid programs typically operate under state procurement regulations that place great emphasis on pursuing the lowest-cost bid if it is “technically acceptable” to reviewers of the proposal. It should be noted that many states include consumers of M/SU services as advisers to the state in the procurement of MBHO carve-out services. Private payers commonly use consultants as advisers in their procurement process.

The market for MBHO carve-out services consists of several large national vendors (e.g., United Behavioral Health, Magellan, and Value-

Options), several smaller national firms (e.g., CIGNA Behavioral Health, PacifiCare Behavioral Health), and numerous smaller regional vendors (e.g., Beacon Health Strategies in the northeast). Competition for contracts is very intense, resulting in aggressively priced bids. In both the public and private sectors, disproportionate weight is usually placed on the cost portion of the proposal. States in particular are reluctant to deviate from awarding contracts to organizations other than the lowest-cost bidder. While private purchasers have greater flexibility in selecting vendors, they, too, commonly place heavy emphasis on price in awarding a contract. This emphasis on price, together with the limited use of quality measures in most procurements, creates an incentive for MBHO carve-out vendors to gear their care management practices to meet cost goals, possibly at the expense of quality. Payers are left to rely on complaints and highly visible indicators of quality deficits to identify a quality-of-care problem.

Widespread evidence shows that MBHO carve-out programs reduce spending on both mental health and substance-use treatment (Frank and Lave, 2003; Frank et al., 1995; Sturm, 1999), although the evidence to date on the impact on quality of care is limited and mixed (Barry et al., 2003; see Frank and Lave, 2003, for a recent review). Studies of early programs typically showed no differences in quality (Busch, 2002; Dickey et al., 1998; Merrick, 1998). Findings of two more recent studies, however, suggest that people with severe mental illnesses may be especially disadvantaged under MBHO carve-out arrangements in the context of state Medicaid programs. Manning and colleagues (1999) compared outcomes for patients with schizophrenia enrolled in a capitated carve-out program with those for similar patients whose care was paid for under fee-for-service arrangements. They found that people with schizophrenia in the carve-out program showed less improvement than those in fee-for-service arrangements (Manning et al., 1999). Busch and colleagues used data from one state Medicaid program to study indicators of the quality of care based on the schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) recommendations. Their comparison of a capitated MBHO carve-out and a primary care case management system found comparable quality of medication management under the two approaches, but substantially lower quality of psychosocial treatment under the capitated carve-out arrangement (Busch et al., 2004).

The above evidence suggests how MBHO carve-out arrangements alter the quality of care relative to fee-for-service arrangements. The more general question is whether existing levels of quality of care are sufficient. The evidence from several studies is that levels of care under both arrangements are lower than desired (Lehman and Steinwachs, 1998; McGlynn et al., 2003; Young et al., 2001).

Purchase of Services by Carve-Out Organizations

Carve-out vendors operate under very specific contracts. These contracts specify the benefit structure within which the MBHO carve-out has responsibility for managing care. They also specify the responsibilities of the carve-out vendor with respect to the services being managed. Payment arrangements, risk bearing, and performance standards are all established, as is the structure of the provider network. Virtually all carve-out contracts exclude prescription drugs from the services managed by the MBHO, as well as from the budget that is to be managed. The implication is that carve-out contracts are not “economically neutral”; that is, there are economic incentives favoring the use of medications over other components of treatment. In effect, psychotropic drugs are “free” to carve-out vendors, while they must pay market prices for hospital care and professional services.

Indeed, empirical analyses of treatment patterns show that patients treated for particular illnesses (e.g., depression) under a carve-out arrangement are more likely to be treated with medication—and medication alone—than are otherwise similar patients whose care is not managed under such a contract (Berndt et al., 1997; Busch, 2002). Other studies have shown that following implementation of a carve-out arrangement, spending on psychotropic drugs has increased, other factors being held constant (Ling et al., 2003; Norton et al., 1999). The result is that savings from carve-out programs come from reduced use of inpatient and outpatient specialty M/SU care. Increases in prescription drug spending serve to reduce some of the savings otherwise realized by the group purchaser.

In modern health care markets, it is rare for a single health plan to cover 30 percent of insured patients in a market. When individual health plans account for 5–20 percent of patients, a typical provider or professional may literally do business with dozens of plans. Thus, a physician may face a dozen formulary arrangements, many sets of clinical guidelines, an array of compensation arrangements, and numerous reporting requirements for any particular condition. In such cases, the impact on provider behavior of financial incentives or other directives specified in any one health plan will be quite diluted. Research has shown that physician practices appear to manage their operations in a manner that is responsive to the overall composition of their payer arrangements (e.g., the most frequent incentive scheme). This means that in general, an individual health plan has little ability to influence provider behavior if its approach differs from that commonly encountered in a practice (Glied and Zivin, 2002).

The MBHO carve-out market has consolidated notably since the early 1990s. At that time, there were nearly a dozen significant national vendors; today there are three or four. The implication is that in local markets for M/SU health care, individual carve-out companies may account for a larger

share of patients than is common in health care generally. It is relatively common for a carve-out vendor to account for 30–50 percent of a market. This means carve-out vendors have the potential to affect the delivery of M/SU health care in a manner that health plans alone cannot. The consolidation of the carve-out marketplace serves to increase the potential bargaining power of the larger carve-out vendors. That bargaining power is achieved because a carve-out vendor can direct patients away from providers that offer prices or other dimensions of performance not consistent with the vendor’s economic and clinical aims. The result is a considerable amount of power not only in setting prices, but also potentially in establishing standards of care.

To date, the MBHO carve-out industry has used its power to (1) increase access to care (as measured by utilization rates), (2) reduce utilization of inpatient care for both mental health and substance-use care, (3) reduce provider payments, and (4) reduce the duration of some ambulatory episodes of treatment. The exertion of pricing power on the one hand contributes to cost control. However, excessive price reductions can decrease the effective supply of providers that are willing to participate in managed behavioral health care networks. This in turn creates the appearance of a shortage for enrollees and managers of those plans, even though there is no shortage in the aggregate. Low prices can result as well in an undersupply of quality (to be discussed further in the context of Medicaid). Yet the consolidation of the market also creates an opportunity to influence provider behavior in the service of quality improvement. The possession of market power with respect to providers means that efforts to improve quality will be less diluted than is typical in the health sector generally. Some managed behavioral health care initiatives have used this market power to both reduce costs and improve quality. When the Massachusetts Medicaid program instituted a managed behavioral health care carve-out program in the early 1990s, the number of inpatient providers supplying care to Medicaid enrollees with M/SU illnesses was reduced by about 30 percent. Hospitals were eliminated from the program based in part on historical performance on quality, as well as price (Callahan et al., 1995; Frank and McGuire, 1997). The result was reduced inpatient spending and constant or improved quality of inpatient care. The implication is that network design can be used to exert economic power not only to control spending, but also to improve quality.

Purchase of Services in Traditional Medicaid Programs

State Medicaid programs typically cover and pay for a wide range of services for the treatment of mental illnesses. Coverage for treatment of substance-use illnesses is far less consistent across the states (McCarty et al.,

1999). On the mental health side, the array of services covered by Medicaid is consistent with the provision of evidence-based treatment. This is often not the case for treatment of substance-use illnesses. Traditional Medicaid programs purchase ambulatory services on a fee-for-service basis. States use a variety of arrangements to pay for hospital services. These range from prospective per diem rates, to per case prospective payment, to the occasional use of prospective budgets. Prescription drugs are paid for under a “most favored nation” arrangement, whereby Medicaid is guaranteed the best private price (Scott-Morton, 1997). Under the traditional Medicaid structure, a state’s ability to use cost sharing to control costs and utilization is minimal. Thus traditional Medicaid relies on setting prices for ambulatory services at rates below market levels. Those prices reduce provider willingness to accept reimbursement and participate in the program. Payment levels are therefore low, and the quantity of care is constrained by the available supply. Data from the mid-1990s show that among physicians, psychiatrists had the lowest rate of Medicaid participation (Perloff et al., 1995). Only about 28 percent of psychiatrists were full participants in Medicaid, compared with 56 percent of all specialists and 36 percent of primary care physicians. These low rates of payment and participation are generally thought to be consistent with lower-quality care (Rowland and Tallon, 2003). Hospital payment rates have also tended to be somewhat lower than market rates; as a result of congressional action and litigation, however, the differential is smaller than is the case for ambulatory services (MEDPAC, 2003).

Publicly Budgeted Systems of Care

The ways in which publicly budgeted M/SU services are organized and funded varies greatly across the 50 states (Lutterman and Hogan, 2001). Substance-use treatment services are far more reliant on direct funding through state and local government than is mental health care (Figure 8-1). Yet while there is tremendous variation in the details of how intergovernmental transfers are designed and organized within both the public mental health and substance-use treatment systems, some common features germane to the analysis of quality are found with considerable frequency.

First, organizations that receive funds directly from state and local government for the treatment of substance use are frequently responsible for geographic catchment areas that serve a defined population. In the case of community mental health centers, nearly 60 percent of revenues represent direct grants and contracts from federal, state, and local government (DHHS, 2002). This figure tends to be even higher for agencies that supply primarily substance-use treatment (Tabulations from the National Drug Abuse Treatment System Survey). Within a defined population, these agen-

cies typically serve individuals with low incomes. Some are “insured” by Medicaid, but many are uninsured (e.g., 20 percent of people with severe mental illness [McAlpine and Mechanic, 2000]).

State and local mental health budgets have been under great pressure for some time. In the first years of the new century, a recession and state budget crises forced cuts in most social service programs. A longer-term problem on the mental health front is that an increasing share of state general fund allocations for mental health services is being allocated to the states’ Medicaid matching obligations (Frank et al., 2003). In the substance-use area, modest growth rates in the funding of the federal block grants to states have further stressed states’ abilities to fund local agencies serving poor people with substance-use illnesses. For example, from 2003 to 2004, the Substance Abuse Prevention and Treatment Block Grant grew by just 1.4 percent (www.samhsa.gov/budget/B2005/spending/cj_12.aspx).

The fact that publicly funded M/SU treatment providers typically are (1) well-established nonprofit agencies with exclusive responsibility for providing treatment for low-income, uninsured populations and (2) funded through grant mechanisms or prospectively set budgets with volume requirements (Alexander et al., 2002; Frank and Goldman, 1989) creates incentives that can conflict with the provision of high-quality care. In effect, these agencies commonly face fixed budgets, excess demand for services (as evidenced by waiting lines), and no competition. Moreover, because agencies are responsible for serving defined populations, there tend to be consumer-based and political pressures to minimize waiting lists and serve as many people as possible (see Lindsay [1976] and Michael [1980] for examples of economic models of public provision of general and mental health care). The result is that economic and political forces reinforce an emphasis on maximizing the number of people served, possibly at the expense of investments in quality. State and local governments have little leverage in such cases even if their goals differ because the agencies are in effect monopoly franchises. Thus, state and local governments concerned about quality levels cannot easily direct consumers to other providers.

PROCUREMENT AND THE CONSUMER ROLE

The purchasing arrangements described above shape the role of the consumer of M/SU treatment services. They also affect the market outcomes stemming from active consumerism.

The modern consumer movement in health care dates back to the 1960s, when President Kennedy set forth a consumer bill of rights in his “Consumer Message” of 1962 (Tomes, 1999). This action coincided with the deinstitutionalization movement in mental health and widespread dissatisfaction with institutional psychiatry. The result was an energized pa-

tient advocacy movement and successful litigation by public interest lawyers on behalf of psychiatric patients. It was during the 1960s and 1970s that people who used M/SU treatment services began to call themselves consumers (Chu and Trotter, 1972). Yet the notion of consumerism in the M/SU sector went beyond that of individuals empowered to exercise choice in the marketplace; rather, it involved the exercise of “voice.” That is, through the strategic use of lawsuits and active lobbying, federal and state governments began to directly address the concerns of patients and their families (Tomes, 1999). In recent years, however, the fragmentation of financing for treatment of M/SU illnesses has made it more difficult to focus the consumer’s voice. For example, the state mental health agency is no longer the primary payer and regulator of mental health services in most states; Medicaid now has that responsibility (Frank et al., 2003).

The consumer role also involves a more commercial or market-oriented set of activities whereby consumers seek to obtain services that offer the mix of price and quality that best suits their needs. This role typically involves obtaining and processing information on the cost and quality of various health care services, including health insurance.

Privately insured people frequently have a choice of health insurance plans. However, evidence to date suggests that consumers make little use of information on quality and frequently focus primarily on price. In the case of those with M/SU illnesses, the selection incentives described earlier lead to the troubling result that greater choice and consumerism tend to compromise the coverage and quality of services offered by health plans. This holds true for Medicaid managed care arrangements that rely on health plans competing for enrollees. The presence of payer carve-outs diminishes consumer choice in coverage for M/SU treatment coverage and focuses choice on providers. In traditional Medicaid programs, there is no insurance choice as is the case in traditional Medicare (Parts A and B).

Insured consumers of treatment for M/SU problems and illnesses (and those covered by Medicare) commonly have a good deal of choice among providers. Like all health care consumers, however, those seeking help for M/SU illnesses must choose among a large number of providers that are highly heterogeneous with respect to training, therapeutic orientation, technical capabilities, and expertise in specific types of problems (see Chapter 7), and there is little consistent information on provider performance in a typical consumer’s choice set. Furthermore, these choices must be made in the context of complex coverage and payment arrangements. It is common for a privately insured person to have coverage for mental health care that involves a deductible, coinsurance, and then a limit on coverage after a specific number of visits or days of care. In addition, some providers are “in network” while others are “out,” which means that coinsurance rates will differ. Also, as discussed previously, consumers of M/SU treatment services

face more-limited coverage—and as a result, higher prices and greater financial risks—relative to other health care consumers, while the economic circumstances of insurance coverage generally make using services considerably more expensive to the household. Finally, M/SU illnesses can affect a consumer’s outlook and attitude toward treatment (e.g., pessimism among those with depression), thereby influencing the ability to exercise commercial aspects of the consumer role.

Consumers who rely on traditional Medicaid or providers that are directly funded by state and local governments have very limited choices of providers. Because budgeted systems are most often organized as franchises that cover catchment areas, consumerism does not play a role in determining the quality or price of services. These are the types of providers that have been the focus of lobbying by advocacy groups and lawsuits by public interest lawyers. Thus consumerism in this subsector has come to mean the exercise of voice. Without fundamental change in the organization of care delivery, the existing consumer role will persist for these individuals. The Medicaid program in theory allows for a broad choice of providers; however, rationing by paying providers fees that are below market rates results in a limited supply of providers willing to treat Medicaid recipients with M/SU illnesses. The end result is that most Medicaid recipients have a very limited choice of providers for M/SU treatment.

EFFECTS OF MARKET AND POLICY STRUCTURES ON QUALITY

The above discussion identifies several key forces that affect the quality of M/SU care according to the main types of funding arrangements (competitive insurance, direct carve-out), under differing methods of organizing the financing of services (carve-out networks, traditional Medicaid), and with differing sources of payment (direct government, Medicaid, private insurance). Each of the main structures identified offers a potential target for policy intervention.

Quality Distortions in the Purchase of Health Plan Services Through Competition for Enrollees

When a group purchaser offers its enrollees more than one health plan from which to choose, most private insurance and many state Medicaid programs create competitive markets in which health plans compete to enroll members. In these cases, incentives to avoid enrolling high-cost individuals may cause distortions in insurance coverage for and the quality of M/SU care. These incentives arise because people with M/SU illnesses generally incur higher health care costs that persist over time relative to other segments of an insured population. Such distortions in private insurance

coverage can be addressed by mandating minimum levels of coverage for M/SU care. “Parity” legislation is an example of such measures. As noted earlier, however, managed care tactics can substitute for demand-side cost-sharing policies (e.g., copayments, limits) to control costs. Under parity laws, health plans continue to have an incentive to avoid enrolling high-cost individuals. By applying the tools of managed care to M/SU services more stringently, plans can affect aspects of the quality of care they provide (e.g., convenience and availability of providers) and make themselves less attractive to potential enrollees who anticipate availing themselves of M/SU treatment services. Thus parity laws appear to be necessary but not sufficient to address selection incentives that distort coverage and quality of care (Frank et al., 2001).

Two approaches to stemming adverse selection incentives in M/SU care are currently in use. The first is payer carve-out of M/SU health care services, whereby the employer or other group purchaser separates M/SU health care from the remainder of insurance risk and eliminates its management as a competitive strategy (see the discussion earlier in this chapter). Coverage and rationing for M/SU health care are arranged directly by the payer with the carve-out vendor through a contract. The payer’s procurement process and the terms of the contract thus become the determinants of rationing (as discussed below). Carve-outs carry their own disadvantages, including relatively high administrative costs, potential difficulties in coordination of care between general medical care and specialty behavioral health providers, and incentives to shift costs and responsibility for care across insurance segments (e.g., pharmacy benefits). It is important to note as well that most carve-out arrangements in private health insurance are not payer carve-outs but are implemented by an individual health plan; these arrangements do not affect selection-related incentives. There is also anecdotal evidence suggesting that some large insurers are shifting away from the carve-out approach to managing M/SU care, as exemplified by Aetna’s recent decision to “carve back in” M/SU health care instead of contracting out for these services.

The second approach to reducing selection incentives is risk adjustment, a strategy consistent with either integration of the risk associated with M/SU health services with other medical risks or a health plan carve-out structure. The idea behind risk adjustment is that if health plans are paid more for enrolling high-cost individuals, they will be less inclined to try to avoid doing so. Most risk adjustment systems rely on patient demographics and clinical information, such as diagnoses, to create clusters of potential enrollees according to the intensity and complexity of past treatment (Weiner et al., 1996). These clusters are used to predict costs. If individuals choose plans based in part on predictable expenses, the risk adjustment approach can be used to adjust plan payments so as to diminish

the selection incentive. However, risk adjustment systems in general explain only about 7 percent of variations in spending. Ettner and colleagues compared the performance of several risk adjustment systems for M/SU services in private insurance and Medicaid. They found that no existing risk adjustment classification system displayed strong predictive ability for spending on M/SU care (Ettner, 2001; Ettner et al., 1998). Thus existing risk adjustment approaches appear to be limited in their ability to stem selection-driven distortions in quality affecting those at risk for using M/SU treatment services. Organizational strategies can also be used to address selection incentives.

Direct Public Purchase of Behavioral Carve-out Services in Medicaid

Currently, approximately 16 states and territories (or substate units) contract directly with carve-out vendors for some M/SU health care services. As discussed earlier, this approach to the purchase of coverage and managed care for M/SU treatment offers the advantage of attenuating distortions in quality of care that may result from selection-related incentives. Yet the procurement process for these contracts is frequently structured so that performance with respect to contract costs may be overemphasized relative to performance on quality of care. If costs and quality are positively correlated, the implication of this procurement structure is that there will be a tendency to choose lower-cost, lower-quality contract proposals. One is reminded of the remarks of astronaut Allen Shepard, who just prior to being launched into space expressed concern that he would be aboard the spacecraft that had been built by the lowest-cost bidder.

One approach to addressing this concern would be to reorient the procurement process toward a two-step procedure. In the first step, states would engage in a rate-finding process. They would collect information on the outcomes of contracting processes in other states and in the private sector and interview potential vendors concerning the costs of their services. They would then analyze these data to determine the “reasonable” costs of providing MBHO services to the state’s Medicaid population. A level of reasonable costs would be selected and announced as the contract “price.” In the second stage of the procurement, interested vendors would submit competing proposals. The proposals would be judged solely on the proposed quality of services, access to care, and ability to coordinate with other systems of care (general medical care, social services, housing, and income support). With the procurement process structured in this way, competition would be reoriented toward offering innovative approaches to improving the quality of clinical services and developing mechanisms for coordination of care with relevant components of the health and human service sectors that offer complementary services. The incentive would be

for vendors to propose the highest-quality program consistent with the announced budget (price(s) times the size of the population(s)).

Private Payer Direct Procurement of Carve-Out Services

Private direct purchasers of carve-out services operate in a somewhat different economic and regulatory environment relative to public direct purchasers. First, private payers are not usually as constrained to choose the lowest-cost bidder. In addition, the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA) constrains the use of risk-based payments to vendors. Second, employers compete in labor markets for employees; one important dimension of this competition is the nature and value of the fringe benefits package. Thus, there are typically weaker incentives driving employers to select vendors solely on the basis of the lowest price. Nevertheless, cost pressures in American business are strong, so that some of the same principles noted in the Medicaid case above could be applied to private purchasers.

Traditional Medicaid Programs

Two core features of traditional Medicaid programs impede high-quality M/SU health care. One is the reliance on setting prices for services below market rates to constrain supply; the result is low participation rates by providers and lower-quality service. The other is extremely limited coverage for substance-use treatment services by some state Medicaid programs. While raising the prices of ambulatory M/SU treatment services would likely serve to increase quality, it is impractical to expect such change under current fiscal conditions in the states. Thus there is little opportunity to ameliorate matters in the context of a system of disaggregated office-based providers. Instead, the best option within the Medicaid program is to create contracts with organizations that can manage budgets for treating groups of patients (the underlying presumption being that a substantial volume of services is currently being allocated ineffectively). These contracts in the extreme might expand use of managed care. Alternatively, specific disease management contracts for illnesses such as depression, schizophrenia, or heroin dependence might be procured. Specialty clinics might also receive contracts for organizing care for particular patient groups. In each case, the ability to reorganize services and manage care might permit sufficient funds to be aimed at treating individual cases so as to improve the quality of care.

Budgeted Systems of Care

It is difficult to introduce change into budgeted systems of care from the top down. The basic economics of the public system are at odds with shifts from well-established practices. The grant-based financing system and the franchise nature of most local public delivery systems for M/SU health care tend to inhibit change. Given existing budget levels, introducing competition appears to be impractical. A more practical candidate for policy attention is the content of the grant-based financing system. Pay-for-performance principles could be introduced into such an environment without creating undue disruption. For example, to ensure some financial stability, the majority of funding could continue to be guaranteed via contracts or grants; however, performance criteria would be used to allocate the remainder (e.g., 25–30 percent) of historical funding levels, along with future increases (distribution of inflation or other budgetary increases).

There are, however, numerous challenges to implementing pay for performance in public M/SU treatment systems. First is the primitive state of performance measurement with respect to both the development of measures and the ability of states to implement such measures (Lutterman et al., 2004). In addition, there is concern that pay for performance would distort quality improvement efforts to focus only on those areas in which measures have been developed and payments are made (teaching to the test). There is also little understanding of how such payment might be structured to maximize quality improvement across, say, a state substance-use treatment system. Finally, it was found that in the substance-use sector, use of treatment outcome as a performance indicator created an incentive to treat the least problematic clients presenting for care (Lu, 1999).

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

The incentives created by competitive insurance arrangements, whereby health plans compete to enroll individuals, can be especially deleterious to insurance coverage for and quality of M/SU health care. Because people with M/SU illnesses are more costly to care for than other types of enrollees and because the costs of treating these illnesses persist over time, health plans have economic incentives to avoid enrolling these individuals—a phenomenon known as adverse selection. These selection incentives result in distorted terms of insurance coverage for M/SU services, as well as distortions in the quality of care. The end result is that competitive insurance markets (private or public) tend to generate quality levels for M/SU care that are too low.

The committee recognizes that none of the measures recommended below will fully address the powerful incentives to avoid enrolling people

with M/SU illnesses in competitive health plans and that each measure involves a unique set of costs, benefits, and practical considerations that may make it more or less attractive to an individual purchaser. However, the committee is persuaded by the strength of existing evidence that addressing selection-related incentives is central to improving the quality of care for M/SU illnesses in the context of competitive health insurance markets.

Recommendation 8-1. Health care purchasers that offer enrollees a choice of health plans should evaluate and select one or more available tools for use in reducing selection-related incentives to limit the coverage and quality of M/SU health care. Risk adjustment, payer “carve-outs,” risk-sharing or mixed-payment contracts, and benefit standardization across the health plans offered can partially address selection-related incentives. Congress and state legislatures should improve coverage by enacting a form of benefit standardization known as parity for coverage of M/SU treatment.

The committee also believes that special attention must be given to state procurement processes, as states are the funders of most M/SU health care. State government procurement regulations typically emphasize choosing the lowest-cost of those contractors submitting proposals that are technically acceptable. Currently, about 16 states choose to purchase behavioral health care carve-out services directly from specialty managed behavioral health care vendors on behalf of their Medicaid programs. Among these states are some that delegate procurement to substate authorities (e.g., counties, regions). A review of state requests for proposals indicates infrequent use of performance measures related to clinical quality in state procurement processes, in part because of the limited availability of well-constructed performance indicators. Performance measures that are specified in requests for proposals frequently focus on administrative services such as telephone response times, claims payment speed, and network size. Taken together, the emphasis on choosing the lowest-cost vendor and the limited use and availability of performance indicators result in an almost exclusive focus on price in the competitive selection of specialty managed behavioral health care carve-out vendors. The result is that vendors have powerful incentives to offer products and services that permit attractive price offers and little counterbalancing incentive to offer high-quality services.

Recommendation 8-2. State government procurement processes should be reoriented so that the greatest weight is given to the quality of care to be provided by vendors.

The committee notes that a number of approaches could be taken to implement this recommendation. A few states have recently adopted approaches that give greater weight to quality. Such a reorientation can likely be accomplished with little risk of incurring “runaway costs” because there is now abundant experience with state procurement of managed behavioral health care services. The range of prices is well known, so that price bids can to some extent be bound in the procurement process. Promising examples of reoriented procurement approaches include assigning relatively low weight to price-related dimensions of a bid and relatively higher weight to proposal features that address quality of care and other aspects of service. A second approach is to engage in a rate-finding process for proposals that sets a price for bids and then focus the competition on the quality and service dimensions of performance.

The committee recognizes that procurement processes in which price is overemphasized at the expense of quality considerations are not limited to public-sector purchasing of managed behavioral health care services, although approaches to purchasing in the private sector are more heterogeneous. Nevertheless, we believe the principles set forth in recommendation 8-2 apply to a substantial segment of private-sector purchasers.

Moreover, a substantial proportion of public M/SU treatment services are purchased through government grants to local providers. These providers are frequently private nonprofit organizations that serve the population of a particular geographically defined catchment area, and are typically well-established organizations having long-standing relationships with state and local governments. Services are purchased most commonly through a system of grants. The grants are awarded subject to the provider’s meeting licensing standards and achieving specified service levels. Funding is frequently set at levels that result in patient queues—indicating excess demand for services. There are few quality-of-care standards forming a basis for accountability for these organizations. Moreover, pressures from excess demand create incentives for local providers to expand the volume of treatment even if doing so results in reduced quality.

The committee recognizes the difficult circumstances within which providers that receive the bulk of their funding directly from state and local budgets operate. Health care for substance-use conditions is especially reliant on these purchasing methods and will be affected more strongly. At the same time, we note that there are currently few inducements for these provider organizations to focus on improving quality of care and adopting evidence-based practices.

Recommendation 8-3. Government and private purchasers should use M/SU health care quality measures (including measures of the coordination of health care for mental, substance-use, and general health conditions) in procurement and accountability processes.

Recommendation 8-4. State and local governments should reduce the emphasis on the grant-based systems of financing that currently dominate public M/SU treatment systems and should increase the use of funding mechanisms that link some funds to measures of quality.

The committee acknowledges the underdeveloped state of performance measurement in M/SU health care (see Chapter 4). However, there is an adequate knowledge base to permit state and local governments to redesign grant-based financing systems incrementally so as to incorporate some simple and meaningful performance indicators. The Washington Circle Group measures for substance-use health care are a case in point. The committee envisions that initial efforts in this regard would tie either new funds or a small percentage of existing budgets to performance indicators as a means of reorienting the management of public M/SU treatment provision toward quality improvement. In this way, the refocusing of accountability would not result in budgetary instability. Over time, as performance measures improved and providers altered their management practices, performance measures might be given greater weight in budget allocations.

REFERENCES

Alexander JA, Lemak CH, Campbell CI. 2002. Changes in managed care activity in outpatient substance abuse treatment organizations 1995-2000. University of Michigan School of Public Health. Unpublished manuscript.

Anderson G, Knickman JR. 2001. Changing the chronic care system to meet people’s needs. Health Affairs 20(6):146–160.

Barry CL, Gabel JR, Frank RG, Hawkins S, Whitmore HH, Pickreign JD. 2003. Design of mental health benefits: Still unequal after all these years. Health Affairs 22(5):127–137.

Berndt E, Frank RG, McGuire TG. 1997. Alternate insurance arrangements and the treatment of depression: What are the facts? American Journal of Managed Care 3(2): 243–252.

Busch SH. 2002. Specialty health care, treatment patterns, and quality: The impact of a mental health carve-out on care for depression. Health Services Research 37(6):1583–1601.

Busch A, Frank R, Lehman A. 2004. The effect of a managed behavioral health carve-out on quality of care for Medicaid patients diagnosed as having schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry 61(5):442–448.

Callahan JJ, Shepard DS, Beinecke RH, Larson MJ, Cavanaugh D. 1995. Mental health/substance abuse treatment in managed care: The Massachusetts Medicaid experience. Health Affairs 14(3):173–184.

Cao Z. 2003. Comparing the Pre HMO Enrollment Costs Between Switchers and Stayers: Evidence from Medicare Working Paper. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge Health Alliance Center for Multicultural Studies.

Cao Z, McGuire TG. 2003. Service-level selection by HMOs in Medicare. Journal of Health Economics 22(6):91–931.

Chu FB, Trotter S. 1972. The fires of irrelevancy. MH Fall 56 (4):6:passim.

CMS (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services). 2004. Medicaid Managed Care Program Summary. [Online]. Available: http://www.cms.hhs.gov/medicad/managedcare/er04net.pdf [accessed December 2, 2005].

CMS. 2005. 2005 CMS Statistics. [Online]. Available: http://www.cms.hhs.gov/MedicareMedicaidStatSupp/downloads/2005_CMS_Statistics.pdf [accessed January 13, 2006].

Cutler D, Zeckhauser R. 2000. The anatomy of health insurance. In: Cuyler AJ, Newhouse JP, eds. Handbook of Health Economics. Amsterdam, the Netherlands: Elsevier. Pp. 563–1644.

Deb P, Wilcox-Gok V, Holmes A, Rubin J. 1996. Choice of health insurance by families of the mentally ill. Health Economics 5(1):61–76.

DHHS (Department of Health and Human Services). 2002 Mental Health, United States 2002, DHHS Publication number (SMA) 3938: Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

Dickey B, Hermann RC, Eisen SV. 1998. Assessing the quality of psychiatric care: Research methods and application in clinical practice. Harvard Review of Psychiatry 6(2):88–96.

Druss BG, Marcus SC, Olfson M, Taniellan T, Elinsin C, Pincus HA. 2001. Comparing the national economic burden of five chronic conditions. Health Affairs 20(6):233–241.

Ellis RP. 1985. The effect of prior-year health expenditures on health coverage plan choice. In: Scheffler, R, Rossiter, L, eds. Advances in Health Economics and Health Services Research. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press

Ettner SL. 2001. The setting of psychiatric care for Medicare recipients in general hospitals with specialty units. Psychiatric Services 52(2):237–239.

Ettner SL, Frank RG, McGuire TG, Newhouse JP, Notman EH. 1998. Risk adjustment of mental health and substance abuse payments. Inquiry 35(2):223–239.

Foote SM, Jones SB. 1999. Consumer-choice markets: Lessons from FEHBP mental health coverage. Health Affairs 18(5):125–130.

Frank RG, Goldman HH. 1989. Financing care of the severely mentally ill: Incentives, contracts, and public responsibility. Journal of Social Issues 45(3):131–144.

Frank RG, Lave J. 2003. Economics. In: Feldman S, ed. Managed Behavioral Health Services. Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas Publisher. Pp. 146–165.

Frank RG, McGuire TG. 1997. Savings from a carve-out program for mental health and substance abuse in Massachusetts Medicaid. Psychiatric Services 48(9):1147–1152.

Frank RG, McGuire TG. 2000. Economics and mental health. In: Cuyler AJ, Newhouse JP, eds. Handbook of Health Economics. Vol. 1B, No. 17. Amsterdam, the Netherlands: Elsevier Science. Pp. 893–954.

Frank RG, Glazier J, McGuire TG. 2000. Measuring adverse selection in managed health care. Journal of Health Economics 19(6):829–854.

Frank RG, Goldman HH, McGuire TG. 2001. Will parity in coverage result in better mental health care? New England Journal of Medicine 345(23):1701–1704.

Frank RG, Goldman HH, Hogan M. 2003. Medicaid and mental health: Be careful what you ask for. Health Affairs 22(1):101–113.

Frank RG, McGuire TG, Newhouse JP. 1995. Risk contracts in managed mental health care. Health Affairs 14(3):50–64.

Fronstin P. 2003. Sources of Health Insurance and Characteristics of the Uninsured: Analysis of the March 2003 Current Population Survey. Washington, DC: Employee Benefit Research Institute.

Glied S, Zivin JG. 2002. How do doctors behave when some (but not all) of their patients are in managed care? Journal of Health Economics 21(2):337–353.

HCFA (Health Care Financing Administration). 1992. HCFA Pub. No. 03339, Report to Congress: Medicaid and Institutions for Mental Diseases. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Hodgkin D, Hogan CM, Garnick DW, Merrick EL, Goldin D. 2000. Why carve-out? Determinants of behavioral carve-out choice among large US employers. Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research 27(2):178–193.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 1993. Field MJ, Shapiro HT, eds. Employment and Health Benefits: A Connection at Risk. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Lehman AF, Steinwachs DM. 1998. Translating research into practice: The schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) treatment recommendations. Schizophrenia Bulletin 24(1):1–10.

Lindsay CM. 1976. A theory of government enterprise. Journal of Political Economy 84(5): 1061–1078.

Ling DC, Berndt EB, Frank RG. 2003. General purpose technologies, capital-skill complementarity, and the diffusion of new psychotropic medications among Medicaid populations. unpublished data. Department of Health Care Policy, Harvard University Working Paper.

Lu M. 1999. Separating the true effect from gaming in incentive-based contracts in health care. Journal of Economics and Management Strategy 8(3):383–432.

Lutterman T, Hogan M. 2001. State mental health agency controlled expenditures and revenues for mental health services, FY 1981 to FY 1997. In: Manderscheid R, Henderson M, eds. Mental Health, United States 2000. DHHS Publication number (SMA) 01-3537. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

Lutterman T, Ganju V, Schact L, Shaw R, Higgins K, Bottger R, Brunk M, Koch RJ, Callahan N, Colton C, Geertsen D, Hall J, Kupfer D, Letourneau J, McGrew J, Mehta S, Pandiani J, Phelan B, Smith M, Onken S, Stimpson DC, Rock AE, Wackwitz J, Danforth M, Gonzalez O, Thomas N, Manderscheid R. 2004. Sixteen state study on mental health performance measures. In: Manderscheid R, Henderson M, eds. Mental Health, United States 2002. DHHS Publication Number (SMA) 3938. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

Manning WG, Liu CF, Stoner TJ, Gray DZ, Lurie N, Popkin M, Christianson JB. 1999. Outcomes for Medicaid beneficiaries with schizophrenia under a prepaid mental health carve-out. Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research 26(4):442–450.

Mark TL, Coffey RM, Vandivort-Warren R, Harwood HJ, King EC, the MHSA Spending Estimates Team. 2005. U.S. spending for mental health and substance abuse treatment, 1991–2001. Health Affairs Web Exclusive W5-133–W5-142.

McAlpine DD, Mechanic D. 2000. Utilization of specialty mental health care among persons with severe mental illness: The roles of demographics, need, insurance, and risk. Health Services Research 35(1 Pt 2):277–292.

McCarty D, Frank RG, Denmead G. 1999. Methadone maintenance and state Medicaid managed care programs. Milbank Quarterly 77(3):341–362.

McGlynn EA, Asch SM, Adams J, Keesey J, Hicks J, DeCristofaro A, Kerr EA. 2003. The quality of health care delivered to adults in the United States. New England Journal of Medicine 348(26):2635–2645.

MEDPAC (Medicare Payment Advisory Commission) 2003. Report to Congress: Medicare Payment Policy. Washington, DC: MEDPAC.

Merrick E. 1998. Treatment of major depression before and after implementation of a behavioral health carve-out plan. Psychiatric Services 49(11):1563–1567.

Michael RJ. 1980. Bureaucrats, legislators, and the decline of the state mental hospital. Journal of Economics and Business 32(3):198–205.

Miller RH, Luft HS. 1997. Does managed care lead to better or worse quality of care? Health Affairs 16(5):7–25.

Normand SL, Belanger AJ, Frank RG. 2003. Evaluating selection out of plans for Medicaid beneficiaries with substance abuse. Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research 30(1):78–92.

Norton EC, Lindrooth RC, Dickey B. 1999. Cost-shifting in managed care. Mental Health Services Research 1(3):185–196.

Padgett DK, Patrick C, Burns BJ, Schlesinger HJ, Cohen J. 1993. The effect of insurance benefit changes and use of child and adolescent outpatient mental health services. Medical Care 31(2):96–110.

Perloff JD, Kletke P, Fossett JW. 1995. Which physicians limit their Medicaid participation, and why. Health Services Research 30(1):7–26.

Rowland D, Tallon JR. 2003. Medicaid: Lessons from a decade. Health Affairs 22(1): 138–144.

Scott-Morton F. 1997. The strategic response by pharmaceutical firms to the Medicaid most favored customer rules. RAND Journal of Economics 28(2):269–290.

Sturm R. 1999. Tracking changes in behavioral health services: How have carve-outs changed care? Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research 26(4):360–371.

Tomes N. 1999. From patients’ rights to consumer rights: Historical reflections on the evolution of a concept. In: Making History: Shaping the Future. Proceedings of the 8th Annual MHS Conference September 7–9, 1999 in Hobart, Tasmania, Australia. Australia and New Zealand: The Mental Health Services Conference Inc.

Weiner JP, Dobson A, Maxwell SL, Coleman K, Starfield B, Anderson GF. 1996. Risk-adjusted capitation rates using ambulatory and inpatient diagnoses. Health Care Financing Review 17(3):77–99.

Young AS, Klap R, Sherbourne C, Wells KB. 2001. The quality of care for depressive and anxiety disorders in the United States. Archives of General Psychiatry 58(1):55–61.