1

Overview

Will you still need me,

Will you still feed me,

When I’m 64?*

Four decades ago the Beatles captured the questions of the baby boomers in their youthful look into the future. If the song were being written today, 74 or 84 might replace 64, but the questions would reflect the same uneasiness about aging. There is great uncertainty about how societies that are top-heavy with older citizens will function. Will people want to work past the traditional retirement age? Will employers hire them? Will people remain healthy and mentally sharp or suffer from increasing infirmities? Will younger people need to provide care for older people, or will older people be self-sufficient and socially engaged?

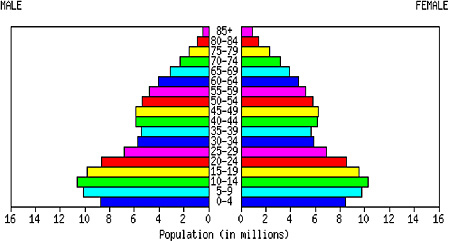

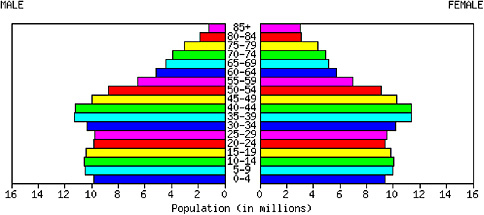

The answers to these questions have major implications for society because of the sheer numbers of the boomer generation and the changing distribution of the U.S. population by age and gender. In 1970, the age distribution of the population, shown in a population pyramid in Figure 1-1, had the broad base and small top typical of a rather young population, but with a bulge near the bottom for the baby boomers and, above that, an indentation for the older “birth dearth” of the Great Depression. By 2000, the age distribution had narrowed at the base, reflecting the larger number of those in midlife and the smaller number of children and young adults; see Figure 1-2. By 2030, the age distribution of the popula-

FIGURE 1-1 1970 age distribution by population.

SOURCE: U.S. Census Bureau, International Database. Available: <http://www.census.gov/ipc/www/idbpyr.html (accessed December 2005).

FIGURE 1-2 2000 age distribution by population.

SOURCE: U.S. Census Bureau, International Database. Available: <http://www.census.gov/ipc/www/idbpyr.html (accessed December 2005).

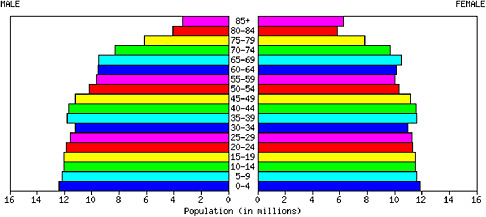

tion will be nearly vertical, with similar numbers of people at every age through midlife and much larger numbers of older adults than at any previous time; see Figure 1-3. By 2030, it is estimated that there will be 12.1 million women and 7.4 million men ages 80 or older, more than twice as many as in the year 2000. In each of the three pyramids, the number of older women is larger than the number of older men.

FIGURE 1-3 2030 age distribution by population.

SOURCE: U.S. Census Bureau, International Database. Available: <http://www.census.gov/ipc/www/idbpyr.html (accessed December 2005).

As policy makers and researchers look at the changing U.S. population, they, too, have questions. To date, most of those questions have focused on the societal level—for example, what are the implications for the economy of an aging workforce? What special policy issues will come to the fore because of the extremely large number of women over 80? Increasingly, however, there are questions at the individual level—for example, how will these older people be different from younger adults and, perhaps, different than they were when they were younger? To answer those kinds of questions about the older population, knowledge is needed from a wide variety of disciplines and fields in social and behavioral sciences.1

COMMITTEE CHARGE AND APPROACH

To help develop that knowledge, the Committee on Aging Frontiers in Social Psychology, Personality, and Adult Developmental Psychology was formed in response to a request from the Behavior and Social Research Program of the National Institute on Aging (NIA). It was charged to:

… explore research opportunities in social psychology, personality, and adult developmental psychology in order to assist the National Institute on Aging in formulating new directions within its present research portfo-

|

1 |

Throughout this report, “old,” “older,” and “elderly” are used interchangeably and refer to people ages 65 and older. Subgroups of this population are defined as introduced. |

lios and to develop a long-term research agenda in these areas. The study committee will identify research opportunities that have the added benefit of drawing on recent developments in the behavioral and social sciences, including behavioral, cognitive, and social neurosciences, that are related to social psychology, personality, and adult developmental psychology, and that cross multiple levels of analysis from molecular to macro-levels.

The committee included clinical, personality, and life-span developmental researchers with expertise in aging, as well as researchers whose expertise was highly relevant to aging, but whose research has not focused directly in the field. Considerable time was spent on two initial tasks: to review what has been learned about aging while considering what still needs to be learned, and to consider how to inform the richly descriptive body of research on aging with cutting-edge empirical approaches from several areas in psychology.

The committee’s work is fundamentally based on a life-span perspective, on the recognition that people at every stage of life embody everything in their lives, from their initial genetic endowments to their recent experiences, from their individual personality characteristics to the social and cultural milieus in which they have grown up and lived. A life-span perspective not only responds to the committee’s charge to consider research from the molecular to the macro level, it also provides a framework in which to begin to bring two disparate areas of research together.

In the field of aging research (gerontology), the corpus of social science research has reflected the efforts—and often the intermingling—of sociology, epidemiology, anthropology, social work, nursing, and psychiatry, as well as psychology. With a handful of important exceptions, experimental social psychology has played a relatively minor role in this research. Because of this history, newcomers to the field sometimes sense a disjuncture between the social science of aging and the mainstream of social psychology, which has been more focused on basic processes and mechanisms involved in attitudes, beliefs, and self-regulation.

In part, the disjuncture reflects the interdisciplinary nature of gerontology and the conceptualization of behavioral science research. In part, it reflects the fact that the early mission of behavioral science research focused on identifying problems of older adults, such as isolation, caregiving, and dementia. However, as life-span psychology emerged and directed attention to normal aging, researchers were increasingly urged to embed individuals in a broad historical, physical, and social context, which involved disciplines and approaches other than those typically considered in the purview of psychology. As cohort differences became increasingly evident, cross-sectional age comparisons, absent broader contextual consideration, became suspect.

The time now is ripe to develop a research agenda that pulls from and

crosses the historical disjunctures between the psychology of aging and mainstream psychology and reaches out to other disciplines.

KEY QUESTIONS

Future generations of older Americans may be healthier or more infirm than today’s elderly; they may work longer or retire earlier; they may maintain active engagement in communities or pursue lives of leisure. These alternative scenarios will have enormous influence on the future of aging societies, and behavior is key to all of them. The seeking and timing of preventive health care and people’s abilities to start—and to sustain—healthy regimens in everyday life are crucial. People who maintain nutritious diets lower their risk of certain diseases. People who get regular exercise and do not smoke experience better outcomes in old age than those who are sedentary and smoke. People who have built strong, lasting social networks are more physically healthy in old age and suffer less cognitive decline than those who have not. Social and economic resources and opportunities form a context in which one may or may not have the power to make any choices at all.

The issue, then, for policy makers, as well as researchers, is how to bring about behavioral changes that will result in optimal outcomes for the majority of the population. That is, one essential societal challenge is to help people arrive at old age as mentally sharp and physically fit as possible and with sufficient economic resources. This challenge entails understanding how people initiate and sustain healthy life-styles. It entails understanding how social influences affect long-range planning. Another equally important challenge is to help people come to old age motivated and engaged. This challenge depends not only on individuals’ social and emotional characteristics and expectations, but also on the beliefs, attitudes, and behavior of employers, family members, and health care providers.

The field of research on aging may be on the threshold of its most exciting period. Much of the essential descriptive work has been done. The time for major theory building is ripe, as is the time to apply basic research findings to solving social problems. Aging may be a journey driven in part by biology, but the tremendous variability in aging, even in identical twins, makes it clear that environmental influences—mediated by emotion, cognition, and behavior—significantly affect its course.

RECOMMENDED RESEARCH TOPICS

In order to carry out our charge from the NIA, the committee had to consider a broad array of topics, fields, and disciplines that relate to aging

and older people. We set two criteria for our recommended research topics: (1) as specified in the charge, they draw on recent and promising work in the social and behavioral sciences; and (2) they offer promise for assisting in the problems of everyday life for older people. The committee sought to identify research opportunities that illuminate fundamental mechanisms and processes in older people that can, in turn, contribute to practical issues in the lives of the nation’s current and future older populations. Our search focused on recent developments in the behavioral and social sciences, including behavioral, cognitive, and social neurosciences, which are related to social, personality, and adult developmental psychology.

The committee did not set criteria about the maturity of a field of research or how active it currently is. Rather the committee identified areas poised to make major advances relatively rapidly given sufficient support.

In addition to the above criteria and a life-span perspective, the committee decided to be highly selective and not to offer the NIA a long list of recommended research topics. Thus, the committee’s recommendations are not intended as an exhaustive list of promising areas, nor do the committee’s selections mean that other areas are not interesting or important. Rather, the committee selected four topics that we concluded met the charge from NIA, represent fertile and promising fields of research, and can contribute to improving the practical aspects of people’s lives.

RECOMMENDATION

On the basis of the needs of the aging population and the benefits to individuals and to society that could be achieved through research, the committee recommends that the National Institute on Aging concentrate its research support in social, personality, and life-span psychology in four substantive areas: motivation and behavioral change; socioemotional influences on decision making; the influence of social engagement on cognition; and the effects of stereotypes on self and others.

The committee recognizes that both interdisciplinary and multilevel approaches are required to address the problems of research on aging. The committee supports the development of integrated interdisciplinary work that will take the best conceptual and measurement work from social, personality, and adult developmental psychology and link it with related concepts and measures from many other disciplines, in order to address important social and health problems of relevance to the mission of the NIA.

For example, the emergence of the new field of social neuroscience, which combines methods and insights from neuroscience, cognition, and

social psychology, is transforming our understanding of behavior. This issue is discussed more fully in the topic chapters that follow and the papers “Measuring Psychological Mechanisms” and “Utility of Brain Imaging Methods in Research on Aging” later in this report.

DEVELOPING A PSYCHOLOGY OF DIVERSITY

Future cohorts of the nation’s older population will be more racially and ethnically diverse than previous or current cohorts. In 2000, slightly more than 15 percent of people ages 65 and older were black, Hispanic, or Asian or Pacific Islander (the largest racial and ethnic groups in the country); in 2030, almost 26 percent will be minorities. Among the oldest old—those ages 85 and older—the change is from 13 percent minority in 2000 to just over 21 percent in 2030.

But the most important fact about the nation’s older population is its heterogeneity. It includes both healthy 75-year-olds who still work and jog every day and frail 75-year-olds in nursing homes. It includes people living with or close to family or friends with whom they are deeply involved and people who live alone, far from family and friends. It includes those born into upper-middle-class families in comfortable suburban neighborhoods, whose lives have followed the expected trajectories through school, work, marriage, and family, and those born into poor families in crowded innercities, whose lives have encompassed constant uncertainties and struggles. And it obviously includes men and women of all sexual orientations and of all ethnicities and races, U.S. born or not.

Gender, race, social class, and ethnicity affect opportunities, skills, and liabilities across life, and they significantly relate to old age outcomes. In addition to these characteristics and experiences, attitudes, motivation, and dispositions are also major determinants of people’s behavior and, thus, of their decisions and further experiences. Subsequently, given the almost limitless possible combinations of characteristics and experiences that people can have, it is not surprising that the range of late-life outcomes is dramatic. This range of individual life trajectories may be the most important characteristic of the nation’s current and future older population.

Although individual-level factors are keys to outcomes in old age, they cannot be considered in isolation from society-level forces. Gender, race, socioeconomic class, culture, and ethnicity provide opportunities to compare outcomes in groups of older people that hold quite different beliefs about aging and display different behavioral and social styles. The NIA has invested significantly in survey research on health disparities between men and women as well as among cultural, racial, and ethnic groups (e.g., Nguyen et al., 2004; Terracciano et al., 2003; Thayer et al., 2003).

RECOMMENDATION

The committee recommends that psychological research help to further clarify whether race, culture, ethnicity, gender, and socioeconomic class are associated with fundamental psychological processes represented in each of the committee’s recommended research areas.

Each of the substantive research areas proposed in this report requires the examination of diverse samples. In this way important questions can be answered, such as how group membership(s) may alter types of challenges encountered by older adults or may influence the array of choices made in daily living or how multiple group memberships along with age can affect the extent to which individuals experience and are affected by stereotyping. Existing research on the topics selected by the committee has produced mostly normative findings with very few studies that explore the range of responses that could be expected of the diverse aging population. Of necessity, therefore, the following chapters are limited mostly to normative results; this state of the science is another reason for the recommendation by the committee to make diversity such a significant research consideration.

SUPPORTING THE INFRASTRUCTURE

The research agenda proposed in this report requires strategies for involving excellent psychologists from many specialties in research on aging. It also requires bringing together social, personality, and developmental psychologists with scholars from other social sciences who are actively engaged in research on aging. Moreover, because the problems of aging represent a combination of biological, psychological, and societal influences, both interdisciplinary and multilevel approaches are required. Implementing such interactive research will require innovative funding that creates conditions for collaboration.

RECOMMENDATION

In order to carry out the committee’s proposed research program, the committee recommends that the National Institute on Aging provide support for research infrastructure in psychology and methods development in aging research, including interdisciplinary and multilevel approaches, in order to make progress in each of the other recommended areas more likely and more rapid.

Currently, the Behavioral and Social Research Program at NIA recognizes the need for aggressive strategies to encourage researchers at universities work across disciplines, as does the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (see “Roadmap” <http://nihroadmap.nih.gov/> [accessed December 2005]).

We strongly support extending these approaches to encourage new partnerships not only across disciplines within a university and across different universities, but also with government agencies, foundations, and professional societies. In particular, we ask the NIH to consider encouraging nonprofit organizations or even universities to apply for NIA funding to administer small grants programs to promote specific aspects of interdisciplinary work.

In order to facilitate collaboration between disciplines, funding mechanisms need to provide for sustained contact between researchers in different disciplines and mutual education in the approaches of each discipline. This could be done at the level of individual researchers, through paired career awards, or at the level of centers, modeled on the R24 infrastructure grants2 or on the grants for transdisciplinary centers.3 In addition, to further encourage developing methods and sharing methods across disciplines, we encourage funding for technical assistance workshops and short courses. (Other ideas for new grant mechanisms are described in the paper “Research Infrastructure” in this volume.)

Methodological and analytical approaches hold special promise for the field of aging research. The measurement of change over time—which is essential to a deep understanding of aging—is also an area in which rapid progress is being made. It is critical that issues of methodology and measurement receive attention and priority: good research depends on the use of appropriate techniques and tools. In the paper “Measuring Psychological Mechanisms” in this volume, the committee offers brief explorations of measurement topics. This paper does not, by any means, cover all the methodological issues that are relevant to research on aging and social psychology, but it highlights some approaches that are particularly relevant to the topics on the committee’s recommended research agenda. They are examples of the kind of cross-fertilization of ideas and techniques that can occur between researchers in psychology and other disciplines in research on aging.

The topics we recommend for a focused research program on aging for the NIA can benefit enormously from the kind of support envisioned by the committee’s recommendation on infrastructure. Flexibility to cross disciplines, foster small-scale efforts, and encourage the development of innovative methodology for approaching the exciting questions in aging research, will lead to major strides in understanding certain key aspects of aging in a short time.

|

2 |

See <http://obssr.od.nih.gov/RFA_PAs/MindBody/MBFY04/Start.htm#infrastructure%20initiatives> (accessed December 2005). |

|

3 |

See <http://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/rfa-files/RFA-RM-04-004.html> (accessed December 2005). |

REPORT STRUCTURE

The next chapter briefly reviews some of the key work and findings from psychology and aging research that provided a foundation for the committee’s recommendations and for the rest of the report. With this foundation, Chapters 3 through 6 detail the questions and issues that should be pursued in our four recommended areas: motivating change, decision making, social engagement and cognitive function, and stereotypes. Throughout these chapters we note the roles of gender, socioeconomic status, race, culture, and ethnicity. Our intensive discussions on these topics led to the conclusion that the broad areas of culture and ethnicities can rarely be studied in isolation; rather, they need to be components of most work in aging, including the committee’s four recommended areas of research.

The papers in the second part of this volume present background material to complement the committee’s report. The first three papers cover topics that relate directly to three of the committee’s recommended research topics: motivating change, decision making, and stereotypes. The four shorter papers discuss methodology and measurement, as described above. The final paper presents additional ideas about the kinds of research funding mechanisms that would facilitate carrying out the committee’s research recommendations.