5

Influence of Marketing on the Diets and Diet-Related Health of Children and Youth

INTRODUCTION

This chapter identifies and assesses the research on the influence of food and beverage marketing on the diets and the diet-related health of U.S. children and youth. The work of this chapter should be understood within the context of what is known about these two areas. Chapter 1 describes the breadth and complexity of these factors as well as their multidirectional quality. Chapter 2 discusses the strong evidence that the food and beverage consumption patterns of U.S. children and youth do not meet recommendations for a health-promoting diet and that an estimated 16 percent are obese. Increasing numbers of children and youth also have a variety of physical and psychosocial problems associated with diet and weight.

Chapter 3 discusses the various factors that influence young people’s food and beverage consumption habits. Chapter 4 reviews the ways in which young people are targeted for food and beverage marketing of both product categories and new product lines. A substantial proportion of such marketing is for high-calorie and low-nutrient foods and beverages. The corporate investment in advertising and other marketing practices is aimed at promoting consumer purchases—which are presumably related to consumption of the product advertised and the dietary practices and diet-related health profiles of today’s children and youth.

This chapter reviews and assesses the evidence that explores various aspects of marketing’s influence on the diets and diet-related health of our young people. The three core sections in the middle of the chapter present

the results of a systematic evidence review of peer-reviewed literature in the area. They include enough of the technical and analytic detail to support the committee’s findings about the contributions of marketing. Prior to these three sections are several that explain how the systematic evidence review was conducted, and following them are sections that address related elements such as comparison with other recent reviews and needed research. Throughout the chapter, care is taken to consider the role of marketing as one of multiple factors influencing diet and diet-related health.

The chapter begins with a description of the systematic evidence review undertaken to assess the influence of marketing on the diet and diet-related health of children and youth, including how it was organized, the criteria used for including evidence, the dimensions addressed, the coding process, the nature of the evidence examined, and the process used to review this evidence. This is followed by three sections that present the results of the systematic evidence review relevant to three relationships: (1) the relationship between marketing and precursors of diet, (2) the relationship between marketing and diet, and (3) the relationship between marketing and diet-related health. The role of factors with the potential to moderate these three relationships is then discussed. Finally, the systematic evidence review and its findings are considered in relationship to the results of other recent reports, and areas for future research are identified. A summary of the key findings concludes the chapter.

SYSTEMATIC EVIDENCE REVIEW

The committee conducted a systematic evidence review in order to investigate and summarize the empirical evidence that is directly relevant to the core question: What is the influence of food and beverage marketing on the diets and diet-related health of children and youth? The committee’s review included 123 published empirical studies identified from a set of nearly 200 in the published literature. Systematic evidence reviews are qualitatively different from meta-analyses or traditional narrative reviews (Petticrew, 2001). Systematic evidence reviews do not involve the statistical synthesis of a set of studies, the technique of meta-analyses, but rather attempt to reduce the inevitable bias from narrative reviews by developing explicit and systematic criteria for study inclusion and for assessing the level of evidentiary support provided by each study. As a result, systematic evidence reviews sometimes include far fewer studies than traditional narrative reviews, but they also typically include more than just randomized controlled trials. For example, this review includes not only many controlled experimental studies, but also many observational studies—both cross-sectional and longitudinal—on the influence of food and beverage marketing on the diets and diet-related health of children and youth.

In addition to supporting a rigorous assessment of a comparatively large body of research, a systematic evidence review is well suited for finding and describing any major gaps in the existing evidence base. The influence of television advertising intended for children, for example, has been studied fairly extensively by academic researchers. However, the influence of Internet marketing techniques, such as advergaming—developed specifically for older children and growing rapidly, unlike television advertising—has not been the subject of a single peer-reviewed, published academic study. A section at the end of the chapter presents recommended research directions derived largely from the committee’s systematic evidence review process.

The Analytic Framework

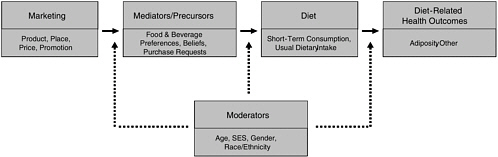

A five-element causal framework (Figure 5-1) was used in assessing the research evidence that related marketing to the diets and diet-related health of children and youth. These elements relate to the marketing-associated elements of the overall ecological schematic presented in Chapter 1.

The arrows in this framework are meant to represent potential causal mechanisms by which marketing might affect diet and diet-related health.1 At the outset, the framework was created from the committee’s identification of likely variables, relationships, and processes if food and beverage marketing were to have an effect on young people’s diet and diet-related health. For each of the major elements in the framework, multiple variables were identified to support the widest possible search for relevant research. As research was identified and reviewed, the framework was revised to better reflect what has been studied.

In the resulting framework, the initiating or exogenous factors are marketing variables. Marketing variables involve the product, such as differences in product formulation, packaging, or portion size; place, such as placement of items at eye level on supermarket shelves or availability in vending machines, convenience stores, or quick serve restaurants; price, such as the price of healthful food in a school vending machine versus the price for less healthful options; and promotion, such as television or billboard advertising. The systematic evidence review focused on marketing intended for young people ages 18 years and younger rather than on the parents of these young people. At the same time, research was included when it addressed marketing techniques that could engage either or both

young people and their parents (e.g., product placement in a popular movie that both young people and parents would watch) if the research reported results for young people.

Marketing might affect diet through a variety of mediators or precursors of diet. In general, a mediator/precursor is a factor through which causal influence passes. For example, if watching television increases obesity, this influence might be mediated by decreasing physical activity, or it might be mediated by increasing calorie intake, or by both. In the causal framework in Figure 5-1, mediators/precursors of diet are intended to capture the factors that could be directly affected by marketing and that in turn might have a direct effect on diet, but which themselves do not involve directly obtaining or consuming food. For example, television advertisements for sweetened cereals aimed at young children are effective when they cause the child to make a request to the person who purchases food for the family. Thus a common mediator to consuming food or beverage products at home is food purchase requests. Other marketing approaches aim to change purchasing behavior through influencing beliefs about what is “cool” to drink, what provides energy, or what constitutes a balanced breakfast. Still other marketing efforts seek to influence a child’s preferences for a product through its association with a well-known character, such as Darth Vader or Tony the Tiger®. Of the studies the committee reviewed on the relationship between a specific marketing factor and a precursor to diet, the great bulk involved food or beverage preferences, beliefs, or purchase requests. Thus the second element in the causal framework consists of a family of factors identified as precursors of diet. Those factors primarily include food and beverage preferences, beliefs, or purchase requests.

The third element in the causal framework is diet. For the committee’s task, diet refers to the distribution and amount of food consumed on a regular basis. Unfortunately, not all studies measured diet comprehensively in this way. Many measured some short-term dietary behavior, such as the number of pieces of fruit or candy consumed in a child-care setting during an afternoon following an exposure to television advertising for fruit or candy that morning. Short-term effects on consumption may or may not translate into longer term effects on a young person’s dietary patterns. Thus, it is important to distinguish studies that considered short-term dietary effects from those that attempted to relate marketing to a more comprehensive measure of diet. Experimental studies tended to focus on short-term consumption following some controlled exposure; cross-sectional and longitudinal studies employed broader measures of usual dietary intake, though they rarely assessed diet comprehensively.

The fourth element in the framework is diet-related health such as obesity, the metabolic syndrome, or type 2 diabetes. Nearly all the empiri-

cal research relating some marketing factor to diet-related health considered some version of the relationship between direct or indirect measures of body fat (adiposity) and television viewing. For simplicity, the term adiposity is used in this chapter to encompass the range of measures in the research reviewed.

The fifth element in the framework is moderators, variables that might alter the cause and effect relationships described in the path from marketing to diet-related health. In this domain, the committee identified age, gender, race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, as well as whether a young person has the opportunity to make independent food purchases, can understand the persuasive intent of advertising, and has accurate nutritional knowledge as a potential moderator.

In general, a moderator is a factor that changes the nature of the causal relationship between two other factors. In the most extreme and simple case, the state of a flashlight’s batteries moderates the influence of the switch on the state of the light. When the batteries are charged, the state of the switch fully determines the state of the light. When the batteries are dead, the switch has no effect whatsoever on the light. In another example, genetic or congenital factors moderate the influence of certain drugs on their intended outcome. For example, the effect of penicillin is quite different among those not allergic. Similarly, certain factors might moderate the effect of marketing on precursors, diet, or diet-related health. For example, the influence of television advertisements on food and beverage preferences might be moderated by cognitive development, as indexed by age. Children under about age 8 generally do not understand the persuasive intent of advertising or the implications of persuasive intent for the nature of the advertising they encounter (Blosser and Roberts, 1985; Donohue et al., 1978; Robertson and Rossiter, 1974; Ward et al., 1977). Presumably, they are more readily influenced by advertising and other forms of marketing than are children older than about 8 years. Income or socioeconomic status might also moderate the effects of marketing on diet. For those in a low-income family, for example, the effect of price might be much stronger than it is for those in a high-income family. Because foods such as fruits and vegetables cost more per calorie than do French fries or cheeseburgers, socioeconomic status may be an important moderator of the influence of fruit and vegetable marketing strategies. In another example, gender may moderate teens’ reactions to marketing for sweet or high-fat foods and beverages. By early adolescence, many girls are concerned about their weight (Story et al., 1995) and, assuming that teens know that consuming sweets and high-fat foods leads to weight gain, they might be more resistant to the marketing of those foods than adolescent boys.

The arrows in the framework are not meant to reflect quantitative

strength, only the possibility of a causal element, and are primarily meant to provide a guide with which to review the relevant research. Nor is the framework meant to be exhaustive. The causal relationships flow only in one direction: from marketing through precursors and so on to diet and diet-related health. Clearly, however, the variables included in the framework might also relate bidirectionally. For example, consumer preferences for sweets or high-fat foods can clearly influence marketing strategies, among other things, influencing product formulation or the product qualities emphasized in advertising. Or, as another example, public concern about diet-related health outcomes such as nutritional inadequacies or obesity can impact product formulation and advertising claims, such as emphasizing fortified, low-fat, or whole-grain products. Such bidirectional relationships require more academic research, and their existence underlines the dynamic complexities noted in ecological perspective presented in Chapter 1.

The framework, then, provides both a causal perspective for the committee’s examination of evidence on the influence of marketing on young people’s diet and diet-related health, and a structure for organizing the empirical research on this topic. Many studies have examined the relationship between a marketing factor and a mediator/precursor. Many others ignored mediators/precursors and examined the relationship between a marketing factor and a measure of diet, and still others ignored precursors and diet, but examined the relationship between a marketing factor and some aspect of diet-related health. The analysis of the evidence presented later in this chapter is organized along these lines: evidence for a causal connection between marketing and mediator/precursor factors first, then evidence for a causal connection between marketing and diet, and finally, evidence for a causal connection between marketing and diet-related health.

Identification of Research for the Review

Unlike narrative reviews, a systematic evidence review includes explicit criteria for which studies to include and which to exclude. In establishing these criteria, the committee sought to create a body of evidence that would be both extensive and directly relevant to its charge of assessing the effects of food and beverage marketing on the diets and diet-related health of children and youth. The committee identified four distinct foci of existing research: industry and marketing sources and peer-reviewed literature; marketing and television advertising; television advertising and media use; and marketing of products other than foods and beverages. These had implications for the criteria used to determine what research was included in the systematic evidence review.

Industry and Marketing Sources and Peer-Reviewed Literature

Marketing research is carried out by many different people and organizations for many different purposes. For ease of discussion, the committee characterized them broadly into two categories: industry and marketing information and peer-reviewed literature. There are some notable differences between them. A large amount of industry and marketing information related to foods and beverages promotion to children and youth is not publicly available, but peer-reviewed literature is in the public domain. Additionally, industry and marketing sources usually focus on specific products or brands, often in comparison to other product categories or brands, whereas peer-reviewed literature is usually directed at understanding the marketing process and related effects across a wide range of product categories.

Marketing and Television Advertising

A large amount of the research about the effect of marketing on young people’s diet and diet-related health examines food and beverage advertising on television. This might be explained by three realities:

-

Advertising is the most visible and measurable component of promotion, one of the classic four marketing practices, the others being product, place, and price;

-

Advertising consumes a substantial and specific portion of a firm’s marketing budget; and

-

Of all food and beverage advertising encountered by children and adolescents, the majority occurs when they are viewing broadcast television and cable television programs.

Understanding the effects of televised advertising in today’s food and beverage marketing on young people’s diets and diet-related health contributes substantially to understanding the effects of broader marketing. Fuller understanding would come with research on other types of promotion in addition to advertising, other venues for advertising in addition to television and cable television, and other types of marketing in addition to promotion (i.e., product, place, and price). The marketing arena is complex and ever changing (see Chapter 4). Considerable work is still needed to develop a full understanding of marketing’s current role, its likely future role, and important options for enhancing its positive role in influencing young people’s diet and diet-related health. For the systematic evidence review, the committee established criteria that included all forms of market-

ing in all venues and vigorously searched for research about marketing other than television advertising.

Television Advertising and Media Use

A number of research studies deliberately use overall amount of television viewing time (primarily at home) as a measure of overall exposure to television advertising, on the assumption that advertising is a part of virtually all television viewing. Measuring home viewing assesses naturally occurring behavior and aggregates it over the many hours a day every day that most young people are watching television. Along with these benefits of measuring overall viewing come various measurement and inference challenges. In assessing the evidence on marketing’s effects, attention was given to the extent to which the measurement and inference problems were addressed when overall television viewing was used intentionally to assess overall exposure to television advertising.

A number of other studies consider overall amount of television viewing per se as an independent variable, particularly in relationship to adiposity. Many are not explicit about the exact mechanisms by which television viewing relates to adiposity or they discuss several different possibilities, often but not always including exposure to advertising for foods and beverages. For example, some of the studies specify that a measure of television viewing is meant to reflect absence of physical activity. The committee established criteria by which all such studies could be included in the evidence base. In these studies, if a relationship was found between television viewing and the outcome of interest, such as adiposity, the reason for the relationship had several plausible explanations for it. Exposure to advertising is one. The committee’s task was to determine for each study of this type whether there was good support for arguing that the relationship of television viewing to the outcome was, indeed, attributable in some degree to exposure to advertising during viewing.

Marketing of Products Other Than Foods and Beverages

There is a substantial body of research on the effect of marketing products other than foods and beverages to children and youth. In general, this research indicates that marketing can influence young people’s beliefs, actions, and preferences. Much of the research has focused on television advertising for toys, but it has also included work on advertising for cigarettes and alcohol, as well as other products and services. A discussion of some of this body of research is included elsewhere in the report, but it was not formally evaluated by the committee for the systematic

evidence review because it does not directly assess the effects of food and beverage marketing.

Final Criteria for Research Included in the Systematic Evidence Review

Based on considerations such as these, the committee’s review was limited to publicly available, scientific studies involving quantitative data on the relationship between (1) a variable involving marketing relevant to young people ages 18 years and younger, and (2) either a variable involving a mediator/precursor, or a variable involving diet, or a variable involving diet-related health.2 Studies that only considered the effect of a moderator variable and had no data pertinent to the relationship between a marketing variable and a precursor, diet, or diet-related health variable were not included. For example, if a study examined the effect of income on attitudes toward fruit and vegetables and had no measure of a marketing variable such as price or placement, then it was not included. Any study that met the inclusion criteria and employed measures that could be interpreted as assessing a marketing variable was included, whether or not the researchers intended the measure to represent that variable. For example, studies were included that used amount of television exposure as the independent variable, or that used attending a high school with Channel One programs (a specially produced high school news program that includes food and beverage advertisements) and examined precursors, diet, or diet-related health.

The criteria for a study to be included in the committee’s systematic evidence review were therefore as follows:

-

Only peer-reviewed, published research that included a full description of methods and results or that directed the reader to another publicly available report that provided the full description of methods. This research could have appeared in print books and journals or e-books and e-journals.

-

Only research reports written entirely in English.

-

Any country as the location for the research.

-

Any publication date.

-

Only original research, no review articles.

-

Only research that reported a quantitative relationship between a variable involving marketing relevant to young people (as opposed to parents only) and a variable involving a mediator/precursor, or diet, or diet-related physical health outcome for young people (as opposed to parents).

-

Any research that used an independent variable that could be interpreted as a measure for some aspect of marketing.

Only published, peer-reviewed research literature was used in this review. There are certain constraints in this respect that apply to any literature review of this sort. It is possible, for example, that investigators have not submitted for publication the results of studies in which the relationship between food and beverage marketing and a pertinent outcome was not statistically significant. In addition, peer reviewers and journal editors may have had a bias to favorably review only those studies in which the results are statistically significant. If so, then the published studies represent only a sample of all studies that have been done, and this sample is biased in the direction of statistically significant relationships between food and beverage marketing and the outcome of interest. However, if such a bias does exist, the direction of that bias should not be assumed as either an increase or decrease in the influence of marketing on the measured precursors, diet, or diet-related health.

Although a publication bias is possible in the research reviewed below, the committee considered the bias, if it exists, to be small. As will be displayed, nonsignificant results have been published in numerous and diverse sources. Moreover, an early examination of unpublished theses, dissertations, and conference papers revealed relatively few nonsignificant findings. Given the importance of the issues, the committee considered it unlikely that well-conceived and well-executed studies were not submitted or were rejected on the grounds that the results were not statistically significant.

Finding the Research

Using the guidelines described above and the many possible variables identified with the initial proposed causal framework, extensive and iterative searches for relevant literature were conducted. Briefly, the quest included an online bibliographic search of several databases, outreach to experts in relevant fields, examining published literature reviews, recourse to committee members’ personal and university libraries, and pursuing references cited in articles that were being coded for the systematic evidence review.

A two-stage process determined whether each item was included in the final systematic evidence review. One or more committee members read the titles and abstracts of more than 200 items and removed any that clearly did not meet one or more of the inclusion criteria. Many review articles, opinion pieces, studies involving adults only, and studies that did not in-

clude a marketing “causal” variable and an “effect” variable that represented a precursor to diet, diet, or diet-related health were removed. The remaining studies were assigned to two people (drawn from committee members and university students commissioned to assist in this process) for complete coding. If the two coders subsequently agreed the item did not meet the inclusion criteria, it was discarded. In the end, the systematic evidence review included 155 research results from 123 studies.

To place this collection of evidence in context, it is helpful to compare this systematic evidence review of the effects of food and beverage marketing on children and youth with the previous most extensive effort. That work, commissioned by the U.K. Food Standards Agency, reflected similar goals and identified 55 articles or entries describing 51 relevant studies for systematic review (Hastings et al., 2003). Building on the base of that work, and applying even more stringent criteria for the publication quality of the studies reviewed, we have been able to identify and assess an even larger body of evidence. Hence, this committee’s review of the evidence represents the most comprehensive and rigorous assessment to date of food and beverage marketing’s influence on children and youth.

Dimensions of the Review

Each research study that met the committee’s inclusion criteria was reviewed and then “coded” on several dimensions that were used in the systematic evidence review for the relationships between the following factors:

-

Marketing and a precursor to diet

-

Marketing and diet

-

Marketing and a diet-related health outcome

If more than one relationship was examined in a published study, a separate entry in the evidence table was created for each such relationship. In some cases this resulted in multiple results for one study. For example, one study examined four matched schools, two of which had Channel One and two of which did not (Greenberg and Brand, 1993). Outcomes measured included the students’ news knowledge, their attitudes toward foods and beverages advertised by Channel One, and their purchases of foods and beverages advertised by Channel One. For the committee’s purposes, student news knowledge was dropped from further consideration, and two entries for the evidence table were created: one representing results for a precursor study of the relationship between Channel One television advertising and food and beverage preferences, and one representing results for a

diet study of the relationship between Channel One television advertisements and usual dietary intake as measured by recent food and beverage purchases.

There were also three other circumstances under which a single publication could contribute more than one result to the evidence table. If a publication reported more than one complete study, each study was represented by at least one result in the evidence table even if each study addressed the same relationship. If a publication employed two or more entirely different samples to test the same question (not to test whether the samples were different), each sample was entered separately into the evidence table. Finally, if a publication utilized different research methods (e.g., both cross-sectional and longitudinal in a panel design) to test the same question, results from each method were entered separately into the evidence table.

Other variations that could have been treated as separate entries in the evidence table were instead incorporated into a single entry. If multiple measures were used in a study to examine a putative result of marketing, then the different measures were described, but only one result—precursor to diet, diet, or health (diet-related health outcome)—was entered into the evidence table. For example, if both skinfold thickness and body mass index (BMI) were used as measures assessing an influence of television advertising, then the entry into the evidence table was “health.” If the research participants came from different age groups from among infants and toddlers, younger children, older children, and teens, the groups were described within one result. If outcomes varied for different subgroups or different measures, they were also described within one result. In assessing the research evidence, it was at times appropriate to consider differences such as these; for example, the relationship of advertising to diet should be examined separately for children and teens. In these cases, the number of items considered in the data tables will be larger than the total number of results in the systematic evidence review table.

Each result in the evidence table was identified by author(s) and publication date of the item in which the result appeared. Its basic characteristics were then coded, three ratings were judged, a mini-abstract was written, and any coder comments were added. Coding the basic characteristics and rating the relevance of the research to the committee’s purposes are described in the next two sections.

Coding the Basic Characteristics

The marketing factor studied was recorded as the “cause” variable, and the precursor, diet, or diet-related health factor studied was recorded as the “effect” variable. For example, in Bao and Shao’s (2002) study of the effect

of radio advertisements for the Cheerwine beverage, “radio advertisements” was recorded as the cause variable, and in the Storey et al. (2003) study of the effect of television viewing on obesity, “obesity” was recorded as the effect variable. If the putative cause variable was television advertising and it was measured by overall television viewing, a special note was made in the coding.

The methods by which the cause and effect variables were measured were also recorded. For example, in Yavas and Abdul-Gader (1993), the cause variable was television advertisements, and its measure was “self-reported average number of advertisement breaks seen each evening.” Its effect variable was food purchase requests, and its measure was “self-reported frequency of advertised product requested (Likert-scale).” In the Storey et al. (2003) study of the effect of television viewing on obesity, obesity was measured by BMI calculated from self-reported height and weight, whereas in the Stettler et al. (2004) study, obesity was measured by BMI calculated from physical measures of height and weight taken by a trained technician and by skinfold thickness measured by the technician in various parts of the body. During assessment of the evidence from the body of research in the systematic evidence review, the cause and effect variables were placed into a small number of conceptual categories, and these were added into the final evidence table.

The kind of research study design was coded. For example, some studies were experiments, a few were natural experiments, many were cross-sectional (observational) studies, and some were longitudinal studies. Also coded were the sample size of the study, the age group(s) of the young people studied, and whether the relationship between the marketing variable and the effect variables was statistically significant at the 0.05 level or better. For all statistically significant results, the relationship was in the expected direction and so not explicitly coded.

Rating the Relevance of the Evidence

Relevance of the evidence for the committee’s tasks was assessed as high, medium, or low on three key dimensions: (1) the strength of the evidence for a causal relationship between a marketing variable and an outcome precursor, diet, or diet-related health variable (causal inference validity), (2) the quality of the measures used in the study, and (3) the degree to which the results in the study generalize to everyday life (ecological validity).

These criteria are not meant to assess the scholarly quality of the research reviewed. It was assumed that the peer-review process screened for this in order for the work to be published. A large, longitudinal study of television viewing and obesity might be designed and executed with impec-

cable care, but because the researchers were interested in establishing an association rather than a cause–effect relationship, its relevance to the committee’s purpose—which prioritizes the ability to make causal inferences—would result in a low rating on causal inference validity. Similarly, a carefully designed and conducted experiment on advertising and children’s product evaluation for two competing brands might be rated high on causal inference validity but, because the experiment was conducted in laboratory conditions quite different from everyday life, it might be rated low on ecological validity. Clearly, such low ratings do not reflect the quality of the research conducted; they reflect the relevance of the research to the committee’s charge to assess the effects of food and beverage marketing on young people’s diet and diet-related health. The two relevance ratings, which will be explained next, both required consideration of the nature and quality of the measures. Measure quality was, therefore, also rated, using the same high, medium, low system used for the two relevance ratings, and it also will be explained below.

Causal Inference Validity Rating. Philosophers, statisticians, economists, epidemiologists, and other social scientists have not yet achieved consensus on the definition of causation, and this debate is likely to go on for some time.3 Agreement is much more substantial, however, on the issue of causal inference, that is inferring from statistical studies the existence or absence of a causal relationship between two particular quantities, such as hours of television watched and calories expended from vigorous physical activity.4

Put another way, accounts of causal inference tend to stress the same points regardless of the precise definition of causation utilized.

The evidence for interpreting an association as causal is entirely distinct from the evidence used to judge whether an association is statistically significant. For example, the evidence required for concluding that a statistical association exists between exposure to television advertising and calories consumed is distinct from the evidence required for concluding that an increase of exposure to television advertising causes an increase in calories consumed. To underscore this distinction, the committee explicitly created two dimensions for each study in the evidence review: one to record whether the statistical evidence for an association was significant, and another to record the evidence for concluding the existence of a causal relation.

The evidence for the existence of a causal relation is a function of the study design, the measures used, and the background knowledge that is credible. The classic design for inferring causation is the randomized experimental trial. Treatment is assigned randomly, and the outcome is measured by some device or person blind to the treatment assigned. If dropout was low, or was independent of treatment, and the outcome was measured validly, then the study provides strong evidence for causality. Experimental studies on the influence of food and beverage marketing were rated high on causal inference validity if treatment was assigned randomly, dropout was not a factor, and the measures used were valid.

In an observational study, that is, a study in which the treatment, or cause variable, was not assigned but rather just passively observed, an association between a putative cause X and a putative effect Y might be explained in three ways: (1) X is a cause of Y, (2) some third factor (confounder) is a common cause of both, or (3) Y is a cause of X. The overall assessment of causal inference validity for such studies rides on how convincingly the study eliminates possibilities 2 and 3.

Time order between the putative cause and effect is the most common reason for eliminating the third possibility, and statistically adjusting, or controlling, for potential confounders is the most common methodology for eliminating the second possibility. To have confidence that statistical controls are adequate, it is important to know both that all important confounders were included in the study and, just as importantly, that all important confounders were measured with high validity, reliability, and precision (see below for explanation). Thus, observational studies were rated high on causal inference validity if the measures of the cause and effect were valid, if all plausible confounders were included and measured validly, reliably, and precisely; and if some reason could be given to eliminate the possibility that the observed association was not due to causation opposite to that predicted, that is, the putative effect causing the putative cause.

To summarize, causal inference validity of each result in the evidence table was scored as high, medium, or low on the basis of the study design, the quality of the measures employed, the drop out rate, the statistical controls used, and the background knowledge available. Because some studies did not aim to make a case for causality, and others faced extremely difficult measurement challenges, judgments about causal inference validity do not and should not coincide with judgments about the scholarly quality of a study. More detail on the criteria used for rating causal inference validity is provided in the codebook (see Appendix F-1).

Measure Quality Rating. Clearly, measurement figures heavily in these judgments. So heavily, in fact, that the quality of measures was explicitly rated as high, medium, or low for each result entered into the evidence table. The measures used in each study were rated taking into consideration three dimensions: validity, reliability, and precision. Validity refers to the extent to which a measure directly and accurately measured what it intended to measure. For example, examining grocery store receipts is a valid measure of food purchased over a week, whereas asking someone to list the food he or she intends to buy over the next week is not. Reliability assesses the extent to which the same measurement technique, applied repeatedly, is likely to yield the same results when circumstances remain unchanged. For example, measuring a 6-year-old’s cumulative exposure to lead by taking a single blood sample is highly unreliable; such measurements fluctuate markedly from day to day. Chemically determining the concentration of lead in discarded baby teeth is much more reliable (ATSDR, 2002). Precision refers to the fineness or coarseness of a measure. For example, measuring family income in number of dollars is precise, but measuring it as low, medium, or high is not.

Ecological Validity Rating. Ecological validity refers to the extent to which a study’s results are likely to generalize to the naturally occurring world of marketing and young people’s diets and diet-related health. An investigation’s research setting might be quite dissimilar to the natural system being studied. For example, a study in which 6-year-olds are removed from class and taken to a trailer near their school, shown 7 minutes of commercials, and then asked to make a series of binary choices from photographs of item-pairs is low in ecological validity. A study in which mother–child pairs are surreptitiously observed in the supermarket and each food purchase request is recorded is more ecologically valid. Also high in ecological validity are studies in which daily television viewing is measured from the use of viewing diaries or program check-off lists. The measure quality may not be high but the ecological validity is high because everyday behavior over a period of time is being measured.

Research on marketing and behavior involves a tension between causal inference validity and ecological validity. Studies that carefully isolate a small number of causal factors in a laboratory setting tend to be high on causal inference validity, but low on ecological validity. Studies that observe young people in their natural environment tend to be high on ecological validity but low on causal inference validity. Rarely do studies score high on both measures.

The Coding Process

Using these dimensions for recording characteristics and for rating measure quality and relevance, the committee constructed an initial codebook and an evidence table. Several iterations of trial coding removed ambiguities from the codebook, calibrated and refined the evaluative criteria employed, and guided final choices about the set of coding dimensions. The final codebook is available in Appendix F-1.

Two coders were assigned to each article identified as relevant to the committee’s purposes. They worked independently and resolved disagreements by discussion. If consensus was not readily obtained, other committee members were consulted. After agreement, both coders’ comments on the article along with an abstract for the piece were included, and the final coding results were compiled into an evidence table that could be sorted on any categorical coding dimension (a condensed version of the evidence table is available in Appendix F-2). Coders were drawn from committee members and selected university students commissioned to assist in this process. All received training to ensure consistency in perspectives and process. In general, coders agreed with each other. Later reviews of the evidence table suggested that both the recording and rating functions were executed consistently by all coders.

Characteristics and Relevance of Research in the Systematic Evidence Review

The systematic evidence review is based on results from published original research about the relationship of commercial food and beverage marketing to diet indirectly through mediators (or precursors), to diet directly, and to diet-related health directly. The descriptive and evaluative characteristics for all the results included in the systematic evidence review are presented in Tables 5-1 and 5-2, respectively, according to whether the result pertained to the relationship of marketing to precursor, marketing to diet, or marketing to diet-related health.

Overall, the results are drawn from many different studies rather than from a few. In total, 123 different published reports of original research

TABLE 5-1 Descriptive Characteristics of Research in the Systematic Evidence Review for the Relationship of Marketing to Precursors of Diet, Marketing to Diet, and Marketing to Diet-Related Health

|

Characteristic |

Marketing and Precursors of Diet |

Marketing and Diet |

Marketing and Diet-Related Health |

|

Total Results* |

45 |

36 |

74 |

|

Decade Published |

|||

|

1970 |

6 |

0 |

0 |

|

1980 |

21 |

10 |

4 |

|

1990 |

10 |

13 |

25 |

|

2000 |

8 |

13 |

45 |

|

Research Design |

|||

|

Experimental |

25 |

10 |

1 |

|

Natural experiment |

1 |

3 |

0 |

|

Longitudinal |

2 |

2 |

17 |

|

Cross-sectional |

17 |

21 |

56 |

|

Age Group |

|||

|

Infants and toddlers (under 2) |

0 |

0 |

1 |

|

Younger children (2–5) |

23 |

12 |

17 |

|

Older children (6–11) |

28 |

22 |

58 |

|

Teens (12–18) |

6 |

10 |

33 |

|

Sample Size |

|||

|

0–49 |

8 |

4 |

1 |

|

50–99 |

10 |

6 |

6 |

|

100–499 |

24 |

16 |

21 |

|

500–999 |

1 |

2 |

11 |

|

1,000 or more |

2 |

8 |

35 |

|

Type of Marketing |

|||

|

TV ads: experimental treatment |

24 |

9 |

0 |

|

TV ads: observed in natural setting |

0 |

0 |

2 |

|

TV ads: TV viewing only |

15 |

22 |

56 |

|

TV ads: TV campaign |

2 |

1 |

0 |

|

TV ads: TV viewing and other media use |

0 |

2 |

16 |

|

All other marketing |

4 |

2 |

0 |

|

Type of Outcome |

|||

|

Preferences |

27 |

0 |

0 |

|

Purchase requests |

14 |

0 |

0 |

|

Beliefs |

13 |

0 |

0 |

|

Short-term consumption |

0 |

9 |

0 |

|

Usual dietary intake |

0 |

27 |

0 |

|

Adiposity |

0 |

0 |

73 |

|

Other |

1 |

0 |

2 |

|

NOTE: Other types of marketing for precursors of diet were print ads, radio ads, multimedia campaign, and price and promotion. Other types of marketing for diet were product placement in film, and price and promotion. Other outcomes for precursors of diet were perceived intent and credibility of ads. Other outcomes for diet-related health were cholesterol levels and cardiovascular fitness. *One result in the evidence table could be about more than one age group or type of marketing. |

|||

TABLE 5-2 Evaluative Characteristics of Research in the Systematic Evidence Review for the Relationship of Marketing to Precursors of Diet, Marketing to Diet, and Marketing to Diet-Related Health

|

Characteristic |

Marketing and Precursors of Diet |

Marketing and Diet |

Marketing and Diet-Related Health |

|

Total Results |

45 |

36 |

74 |

|

Quality of Measures |

|||

|

High |

5 |

10 |

0 |

|

Medium |

27 |

14 |

32 |

|

Low |

13 |

12 |

42 |

|

Causal Inference Validity |

|||

|

High |

11 |

11 |

1 |

|

Medium |

20 |

9 |

18 |

|

Low |

14 |

16 |

55 |

|

Ecological Validity |

|||

|

High |

13 |

24 |

63 |

|

Medium |

19 |

10 |

9 |

|

Low |

13 |

2 |

2 |

contributed 155 different results to the systematic evidence review. On average, then, each publication accounted for 1.26 results in the evidence table. Across all three relationships, no single publication accounted for more than two results in the evidence table. When analyses delved into possible differences by age or by type of outcome, one publication could contribute more than two data points if it involved more than one age group or type of outcome. As will be discussed later, there is a clear need for more research in several areas. However, any finding that can be drawn from the research that has been done to date is based on a diverse set of studies conducted by different researchers. This fact enhances the credibility of the results.

The research spans four decades. During that time, issues addressed early on have also been addressed recently. The first few publications appeared in the 1970s, many appeared in the 1980s and 1990s, and many more have appeared halfway through the 2000s. For any of the three relationships for which findings can be drawn based on early research, there is also recent research that supports the finding and thereby reduces concern that earlier results on any of the three relationships might be different now due to societal changes (e.g., in the nature of food products or of beverage advertising).

All three main types of research designs have been used to study the

direct relationship of marketing to precursors, diet, and diet-related health. For any one relationship, at least two experimental, cross-sectional, and longitudinal research designs have been employed in sufficient numbers so that the usual limitations of one design are generally counterbalanced by the usual strengths of another design. This is true particularly in terms of the ability to determine cause and effect relationships (causal inference validity) and to relate research results to phenomena in everyday life (ecological validity).

Overall, quality and relevance are reasonably good for the research included in the systematic evidence review. Earlier in this chapter the use of high, medium, and low ratings of measure quality, ability to infer causality, and similarity to everyday life was described. These three ratings were made for every result for each of the three relationships examined. Considering the three rating scales and three relationships together, with one exception, the number of medium and high ratings is greater than or about the same as the number of low ratings. The one exception is the causal inference validity rating for research on the relationship of marketing to diet-related health. About three-quarters of the results had low causal inference validity. Thus, it was much harder to arrive at findings about the relationship of marketing to diet-related health than it was to arrive at findings for the relationship of marketing to precursors of diet or to diet itself.

In social science research in general, it is difficult—but not impossible—to achieve in the same study high ability both to determine cause and effect relationships and to relate results to everyday life. It is true as well in the specific area of the relationship of marketing to the precursors of diet, the diets of young people, and their diet-related health. In fact, just 5 (3 percent) of the 155 results had high ratings for both causal inference validity and ecological validity. Three different high relevance studies (French et al., 2001a; Gorn and Goldberg, 1982; Greenberg and Brand, 1993) each contributed one result about the relationship between marketing and diet, and one (Robinson, 1999) contributed one result about the relationship between marketing and diet and one result about the relationship between marketing and diet-related health. Because of this pattern of rather inverse relevance ratings for causal inference validity and ecological validity, which is characteristic of research addressing many different social issues, findings must be carefully drawn from all available research, weighing the contribution of each result and the characteristics and relevance of the research in which it was reported.

Research samples ranged in size from a low in the 30s to a high of more than 15,000, with the majority either in the low 100s or more that 1,000. Overall, older children were the most frequently studied, but different age groups were studied for the three relationships. For the relationship of marketing to precursors of diet, most of the research involved younger

(ages 2–5 years) and older children (ages 6–11 years), with some work with teens (ages 12–18 years). For the relationship of marketing to diet, most of the work involved older children, with quite a bit of work equally with younger children and teens. For the relationship of marketing to diet-related health, most of the work involved older children, then teens, and then younger children. The one study with infants and toddlers (under 2 years) was in this last area, diet-related health. Because of these variations in the ages of research participants and the possibility that age might moderate the relationships between marketing and precursors, diet, or diet-related health, findings were limited to those age groups for which enough research had been conducted.

Nearly all the research was about television advertising, which is the most prominent and frequent type of marketing young people encounter. Just 6 results (Auty and Lewis, 2004; Bao and Shao, 2002 [2 results]; French et al., 2001a; Macklin, 1990; Norton et al., 2000) of the 155 total were about any other type of marketing. The main types of outcomes were food and beverage preferences, purchase requests, and beliefs for the precursors of diet; short-term consumption and usual dietary intake for diet; and adiposity for diet-related health.

Overall the research included in the systematic evidence review was of sufficient size, diversity, and quality to support the derivation of several findings about the influence of marketing, specifically television advertising, on the precursors of children’s and teens’ diet, on their current diet, and on their diet-related health. Following a discussion of how the results in the evidence table were interpreted, the evidence and findings from it will be presented in three sections, first for the precursors of diet, then for diet, and finally for diet-related health.

Interpretation of the Results

Many factors were brought into play in deriving findings from the systematic evidence review. The quantity, variety, and statistical significance of results and the research from which they came influenced whether any finding was drawn and how definitive it was held to be. Pertinent results needed to be available from several different studies conducted by different researchers using different research populations and measures. A preponderance of pertinent results had to support the finding. In addition, any consistent differences between results supporting and not supporting the finding had to be taken into account. If a cogent explanation could be provided for results supporting and not supporting the finding, then the finding would need to be qualified accordingly.

Because of the committee’s charge, particular attention was given to assessing cause and effect relationships and to establishing the degree to

which such relationships are likely also to occur in everyday life in the United States. Useful findings might describe relationships between marketing and precursors, diet, or diet-related health, without being certain that one causes the other. Useful findings also might describe cause and effect relationships, without being certain that they would occur in everyday life. The most useful findings will describe the ways in which various aspects of marketing influence various aspects of precursors of diet, diet, or diet-related health, and do so with some confidence that these effects occur in the everyday lives of our young people.

In deriving findings from the systematic evidence review, the committee used a three-step process. First, it determined whether there were enough research results from which to derive a finding about a particular topic. For example, regarding the influence of televised food and beverage advertising on children’s and teens’ short-term consumption, the committee concluded there was enough evidence for both younger and older children, but “an absence of evidence” for teens. Second, for those topics for which there was sufficient evidence, the committee drew on all aspects of the evidence to decide whether there was a relationship between the marketing variable and the outcome variable. For example, there was sufficient evidence to reach findings about the relationship of televised food and beverage advertising on children’s and teens’ usual dietary intake. For younger and older children, on balance, the evidence supported the finding that advertising influenced intake, whereas for teens, on balance, the evidence supported the finding that advertising did not influence intake. Third, the committee provided a sense of the strength of the research support for the finding, using the terms “strong,” “moderate,” and “weak.” For example, for the findings regarding advertising’s influence on usual dietary intake, there was moderate evidence for such influence for younger children (ages 2–5 years), weak evidence for such influence for older children (ages 6–11 years), and weak evidence against such influence for teens (ages 12–18 years).

A rather large number of results in the systematic evidence review measured everyday television viewing as a means of assessing exposure to food and beverage advertising on television. This was a deliberate measurement choice by many of the researchers who conducted the studies included in the systematic evidence review for the relationship of marketing to precursors of diet and for the relationship of marketing to diet. In cases reviewing the relationship of marketing to diet-related health, researchers generally did not use television viewing to measure exposure to televised advertising. In such studies, television viewing was treated as a measure of several different possible variables, of a sedentary lifestyle, of time away from physical activity, and the like. Nonetheless, the research design, methods, and analyses were essentially the same as those in many studies testing

marketing’s influence on precursors of diet and on diet. For this reason, the committee included all such research in the systematic evidence review, whether or not the researchers intended their work to be about television advertising.

The committee’s decision to accept that measures of television viewing could be interpreted as assessing young people’s advertising exposure had two important ramifications. First, studies that relied on estimates of time spent watching television as an indicator of advertising exposure could not fare very well in terms of the rated measurement quality. This stems from several factors, including the possibility that part of any person’s total television time was devoted to viewing mostly noncommercial programming (e.g., public broadcasting) or that some people may leave the room during commercials, successfully avoiding exposure to the ads. Despite these possibilities, broad-based estimates of time spent watching television function reasonably well to identify an individual’s relative exposure to commercial messages, as advertising permeates the large majority of television viewed by most individuals, in particular young people.

A second important ramification of having included these studies in the systematic evidence review is that the committee must accept the burden of carefully considering alternative explanations for any association found between television advertising, measured by television viewing, and precursors of diet, diet, or diet-related health. This burden increases as one moves from precursors such as requests for foods known to be advertised on programming popular with children, to aspects of diet such as short-term choices for snacks known to be advertised on television, to health issues related to the quality of a young person’s usual diet.

To arrive at findings when television viewing was the measure of exposure to televised food and beverage advertising, plausible alternative explanations had to be generated for each outcome variable and the possibility of ruling out these alternatives examined. This was easier when the same relationship was studied with experimental methods as well as cross-sectional methods. Longitudinal methods were also informative. In addition, research that included methodological and statistical controls for alternative explanations was useful. In the absence of very well-controlled studies or a body of research that includes experimental as well as correlational methods, however, it was hard to draw many findings from research using television viewing as the measure of exposure to television advertising.

Finally, in interpreting the results, the committee kept in mind that diet and diet-related health are complex and multiply determined. There was no expectation that marketing would be the only influence on diet or diet-related health, nor did it seem likely that marketing would be the major determinant of diet or diet-related health. Moreover, people are forgetful

and changeable enough that any limited marketing experience was not expected to have more than a limited influence. With these realities in mind, the committee looked for all possible effects, including powerful and long-lasting effects on diet and diet-related health, but it also considered small effects and short-term effects both reasonable and meaningful.

Overall, the research results included in the systematic evidence review were of sufficient quality, diversity, and scope to support certain findings about the influence of marketing, including the overall finding that food and beverage marketing influences the preferences and purchase requests of children, influences consumption at least in the short term, is a likely contributor to less healthful diets, and may contribute to negative diet-related health outcomes and risks.

Presentation of the Systematic Evidence Review Analysis

The next three sections review in detail the evidence related to each of the three specific relationships. They have a similar structure. To begin, the evidentiary base for the relationship between marketing and the relevant outcome (precursors, then diet, then diet-related health) is considered in terms of the descriptive and evaluative characteristics of all significant and nonsignificant results for that relationship. Because the evidence for all three relationships is almost entirely about one form of marketing—advertising distributed via television and cable television—and a limited set of outcomes, any result about a different form of marketing or an infrequently studied outcome is then removed from the evidentiary base, and the main analysis of the results proceeds. This analysis takes into account the age of the research participants, the kind of outcome, and the causal inference validity for each significant and nonsignificant result. Each section ends with a summary of the important findings drawn from the available research about the target relationship.

In presenting the results of the systematic evidence review for the three relationships, the committee has sought to meet the likely interests of readers with varying levels of expertise in social science research. Many data tables are presented. The main points to be drawn from the tables are also described in terms that should be meaningful to all readers. Examples from the research are offered to bring life to the work. The text, particularly the introduction and findings for each of the three sections, should be useful for every reader. For some, the middle sections, the data tables, the summary evidence table (available in Appendix F-2), and references should provide enough of the analytic methods and results to support an independent assessment of the committee’s work.

SYSTEMATIC EVIDENCE REVIEW OF THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN MARKETING AND PRECURSORS OF DIET

This section considers the evidence relevant to the effect of marketing on precursors of diet. In order for food and beverage marketing to influence young people’s diets, one or more of several things need to occur as the result of marketing. Young people need to become aware of the product or brand or service. They need to develop some sense that consuming the food or beverage is desirable, perhaps because they expect it will taste good, give them energy, cost just a little, be easy to acquire or consume, be fun to handle, be sold in a fun environment, have a toy in the package, help them fit in with their peers, promote strong bones and teeth, please their parents, or provide some other benefit. They may need to influence their parents, older siblings or friends, or caretakers to purchase the product or brand or to go to the restaurant. In the five-element causal framework (see Figure 5-1), these relationships between marketing and the precursors of diet initiate the path from marketing to diet and diet-related health, the primary outcomes of interest to the committee.

Evidentiary Base

For the systematic evidence review of the relationship between marketing and precursors of diet, the evidence table includes 45 results from 42 different published research reports. The earliest study was published in 1974 and the latest in 2005. Table 5-3 summarizes the descriptive characteristics of those studies that reported a statistically significant relationship between any form of marketing and any mediator or precursor, and of those that reported a nonsignificant relationship. All significant results show that more exposure to marketing is associated with greater preference or more purchase requests for what was advertised or more beliefs like that presented via marketing. Virtually all studies in the systematic evidence review focused on marketing of high-calorie and low-nutrient foods and beverages, either due to researcher selection for an experiment or due to the predominant marketing of such products in naturalistic studies. Thus, most of the systematic evidence review focuses on the effects of marketing high-calorie and low-nutrient foods and beverages. No information is included that demonstrates whether the findings would apply to the marketing of more healthful foods and beverages (see Chapter 6 for a discussion of social marketing campaigns).

All but four of the results involved television advertising, occasionally using commercials the researchers had made, often using commercials taken off the air, and sometimes using a measure of likely exposure to commercials as a result of everyday television viewing. For more recent studies, television might include material available via cable television rather than

TABLE 5-3 Descriptive Characteristics of Research on the Influence of Commercial Marketing on the Precursors, or Mediators to Young People’s Diets

|

Characteristic |

Significant Results |

Nonsignificant Results |

|

Total Results* |

35 |

10 |

|

Decade Published |

||

|

1970 |

5 |

1 |

|

1980 |

13 |

8 |

|

1990 |

9 |

1 |

|

2000 |

8 |

0 |

|

Research Design |

||

|

Experimental |

18 |

7 |

|

Natural experiment |

1 |

0 |

|

Longitudinal |

2 |

0 |

|

Cross-sectional |

14 |

3 |

|

Age Group* |

||

|

Younger children (2–5) |

17 |

6 |

|

Older children (6–11) |

21 |

7 |

|

Teens (12–18) |

6 |

0 |

|

Sample Size |

||

|

0–49 |

7 |

1 |

|

50–99 |

7 |

3 |

|

100–499 |

18 |

6 |

|

500–999 |

1 |

0 |

|

1,000 or more |

2 |

0 |

|

Type of Marketing |

||

|

TV ads: experimental treatment |

18 |

6 |

|

TV ads: TV viewing only |

12 |

3 |

|

TV ads: TV campaign |

2 |

0 |

|

Print ads |

0 |

1 |

|

Radio ads |

1 |

0 |

|

Multimedia campaign |

1 |

0 |

|

Price and promotion |

1 |

0 |

|

Type of Precursor* |

||

|

Preferences |

19 |

8 |

|

Purchase requests |

13 |

1 |

|

Beliefs |

10 |

3 |

|

Intent and credibility of advertising |

1 |

0 |

|

*One result in the evidence table could be about more than one age group or type of precursor. For these two characteristics the column totals can be more than the number of results. |

||

broadcast systems. The remaining four results addressed the influence of print advertising (Macklin, 1990), radio advertising (Bao and Shao, 2002), a multimedia advertising campaign (Bao and Shao, 2002), and price and promotion (Norton et al., 2000). Twenty-three of the results were about

younger children (ages 2–5), 28 about older children (ages 6–11), and 6 about teens (ages 12–18).

Twenty-seven of the results examined the effects of food and beverage marketing on young people’s preferences. Most were experiments; some were cross-sectional designs. As an example of an experiment, Borzekowski and Robinson (2001) showed two short cartoons to preschoolers, half of whom also saw about 2.5 minutes of educational material between the two cartoons and the other half of whom saw 2.5 minutes of ads. All material had been broadcast previously on television. The advertisements were for juice, sandwich bread, donuts, candy, a fast food chicken entrée, snack cakes, breakfast cereal, peanut butter, and a toy. Immediately after viewing, children who saw the advertisements preferred the advertised brand over an alternate similar product with similar packaging, even if the advertised brand (of donut) was unfamiliar and the alternate was a local favorite. Advertisements varied in effectiveness, and advertisements run twice were more effective. The advertising effects were the same for boys and girls, children whose home language was English or Spanish, and children with varying levels of access to media. Parents also reported that television advertising influenced their children’s preferences and purchase requests.

Fourteen of the results examined the effects of food and beverage marketing on young people’s purchase requests. Somewhat more than half were cross-sectional designs; the rest were experiments. As an example of a cross-sectional design, Isler et al. (1987) had mothers of 250 children between ages 3 and 11 years keep detailed diaries for 4 weeks. Weekly in-person or telephone checks were made. For younger and older children, there were small, statistically significant relationships between the amount of television watched and the total number of requests and between the amount of television watched and the number of requests for cereal and candy; relationships were not significant for fast foods and snack foods, nor for foods such as fruits and vegetables that are advertised infrequently on television. In an experimental study, Stoneman and Brody (1982) had young children view a 20-minute television cartoon with or without advertisements for two candy bars, one chocolate drink mix, one brand of grape jelly, and two salty snack chips. Mothers separately viewed the cartoons without advertisements and did not know whether their children were seeing advertisements with the cartoons. Mothers and children then participated in a “separate study” of family shopping for weekly groceries in a mini-grocery store. A “clerk,” who was unaware of the nature of the research, surreptitiously recorded what happened. Children who had seen the commercials more often asked for products, whether or not advertised, pointed to them, grabbed them off the shelf, or put them into the grocery cart; they also did so more often for the advertised products. Mothers of these children also more often said no, put items back, and offered alterna-

tives to children’s requests. The article does not say whether children who had seen the commercials ultimately took home more requested products themselves.

Thirteen of the results examined the effects of food and beverage marketing on young people’s beliefs about foods and beverages. The majority was experiments, a few were cross-sectional designs, and one was a longitudinal panel study. As an example of a cross-sectional study, Signorielli and Staples (1997) administered questionnaires to about 400 fourth and fifth graders. Children who viewed more television knew less about which foods and beverages were healthier, and the significant relationship remained when the effects of gender, race/ethnicity, reading level, parents’ education, and parents’ occupation were all also taken into account. More recently, Harrison (2005) carried out a similar study except that children were measured twice, 6 weeks apart, for beliefs about healthier food choices offered as pairs. There were two diet food items (fat-free ice cream versus cottage cheese and Diet Coke versus orange juice, with the italicized choice being healthier) and four nondiet food items (celery versus carrots, rice cakes versus wheat bread, jelly versus peanut butter, and lettuce versus spinach). Taking into account at time 1, grade, and gender, the more children watched television at time 1 the less accurate their choices at time 2 for diet foods (both pairs have items likely to be advertised on television) but not for nondiet foods (only one of four pairs has items likely to be advertised on television).

Table 5-4 summarizes the evaluative characteristics of the 45 results included in the evidentiary base for the relationship between marketing and precursors of diet. Measurement quality was high for 5 results, medium for 27, and low for 13. Eleven of 45 were of high relevance to inferring a causal connection from marketing to the precursors of diet, 20 were of medium relevance, and 14 were of low relevance. The ability to generalize from these studies (ecological validity) was generally good. Thirteen studies were of high ecological validity, 19 medium, and 13 low. A closer examination of the distribution of significant and nonsignificant results according to the relevance of the research, specifically the ability to make a clear causal inference and the ecological validity, also revealed no difference in relevance between the studies reporting significant results and those reporting nonsignificant results (see Table 5-5). As the relevance of the research increased (high or medium ratings compared to low), the proportion of significant results remained high, providing further confidence in evidence-based findings for the influence of marketing on young people’s preferences for, purchase requests of, and beliefs about foods and beverages.

TABLE 5-4 Evaluative Characteristics of Research on the Influence of Commercial Marketing on the Precursors, or Mediators, of Young People’s Diets

|

Characteristic |

Significant Results |

Nonsignificant Results |

|

Total Results |

35 |

10 |

|

Quality of Measures |

||

|

High |

5 |

0 |

|

Medium |

21 |

6 |

|

Low |

9 |

4 |

|

Causal Inference Validity |

||

|

High |

9 |

2 |

|

Medium |

15 |

5 |

|

Low |

11 |

3 |

|

Ecological Validity |

||

|

High |

11 |

2 |

|

Medium |

14 |

5 |

|

Low |

10 |

3 |

TABLE 5-5 Relevance Ratings of Research on the Influence of Commercial Marketing on Precursors, or Mediators, to Young People’s Diets

|

Causal Inference Validity |

Ecological Validity |

Significant Results |

Nonsignificant Results |

|

Total Results |

|

35 |

10 |

|

High |

High |

0 |

0 |

|

|

Medium |

5 |

1 |

|

Low |

4 |

1 |

|

|

Medium |

High |

4 |

0 |

|

|

Medium |

5 |

3 |

|

Low |

6 |

2 |

|

|

Low |

High |

7 |

2 |

|

|

Medium |

4 |

1 |

|

Low |

0 |

0 |

Relationships Between Television Advertising and Precursors of Diet

Given the descriptive characteristics of research about the relationship of marketing to the precursors of diet, any findings about this relationship must be findings about the relationship of television advertising to food and beverage preferences, purchase requests, and beliefs among children and teens. To create a dataset that only examined these relationships, four

TABLE 5-6 Distribution of Significant and Nonsignificant Results by Causal Inference Validity for the Relationship of Television Advertising to the Food and Beverage Preferences of Younger Children, Older Children, and Teens

|

Causal Inference Validity |

Younger Children (2–5 years) |

Older Children (6–11 years) |

Teens (12–18 years) |

|||

|

Significant Results |

Nonsignificant Results |

Significant Results |

Nonsignificant Results |

Significant Results |

Nonsignificant Results |

|

|

Total Results |

7 |

4 |

12 |

5 |

2 |

0 |

|

High |

2 |

1 |

6 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

|

Medium |

5 |

2 |

6 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

|

Low |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

results (from three articles: Bao and Shao, 2002; Macklin, 1990; Norton et al., 2000) were removed. The overall patterns of descriptive and evaluative characteristics and relevance ratings of the remaining 41 results did not change when results involving marketing other than television advertising and precursors other than preferences, requests, and beliefs were removed.