1

Introduction

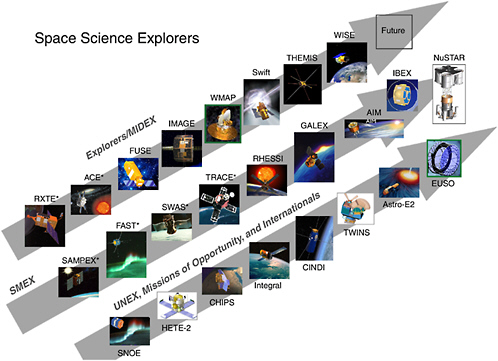

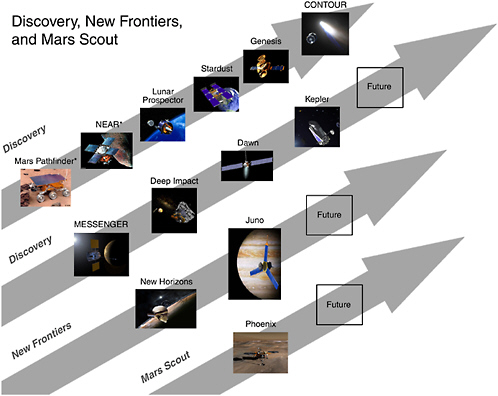

A principal investigator (PI)-led mission is a complete cost-capped, focused space or Earth sciences mission whose concept, including design, development, launch, operations, and scientific analysis, is proposed by a single principal investigator.1 PI-led missions represent an alternative to NASA’s agency-managed missions for carrying out investigations from space-based platforms. PI-led mission programs in the space sciences, which are the subject of this report, include Explorer, the oldest of the programs, with opportunities in the heliophysics and astronomy and physics subdisciplines (Figure 1.1). The remaining three PI-led programs are shown in Figure 1.2: Discovery, with opportunities for solar system exploration, extrasolar planet searches, and astrobiology subdisciplines; New Frontiers, for larger solar system exploration missions in designated science areas; and Mars Scout, which is dedicated to Mars exploration goals.

NASA does not provide a definition of a PI-led mission other than to describe the role of and requirements for PIs and PI-led missions in the announcements of opportunity (AOs). The definition provided in this report is derived from a consideration of the most recent AOs for the Discovery, Explorer, Mars Scout, and New Frontier mission lines (see Appendix C) and the committee’s interviews with and inputs from PI-led mission program and project participants.2

The primary characteristic of PI-led missions is that NASA entrusts the scientific, technical, and fiscal management to a single PI and his or her teams. The PI has the responsibility for defining the mission concept and controlling its cost, schedule, and targeted scientific investigation. PIs are usually the originators of the mission concepts they lead but may be recruited by a concept development team at a NASA center, university, or other entity to lead an effort. The PI chooses and organizes the implementation team and decides how the project resources can best be used to accomplish the mission’s scientific goals. The management arrangements established by a PI can and usually do vary significantly both from program to

FIGURE 1.1 Explorer missions. An asterisk denotes an early-style PI mission. Full names of missions are in Appendix H. Images courtesy of NASA.

FIGURE 1.2 Discovery, New Frontiers, and Mars Scout missions. An asterisk denotes an early-style PI mission. Full names of missions are in Appendix H. Images courtesy of NASA.

program and from mission to mission within a PI-led program. The launches are typically supplied by NASA, though the PI may arrange for a launch through commercial, defense establishment, or international partnering. Mission operations may or may not utilize NASA facilities. In some cases, the PI’s home laboratory or university takes direct responsibility for creating the mission development team as well as for integrating and testing the spacecraft and instruments. In other cases, an outside laboratory, a NASA center, or an industry teammate implements the mission, with the PI providing oversight and decisions in trade studies and adjustments of scope. Some PIs take a very hands-on approach to all aspects of the mission and may be deeply involved in the nuts and bolts of implementation. Others delegate day-to-day responsibilities and technical authority to a project manager and focus on the scientific aspects of the mission or high-level matters such as managing the interfaces with the Program Office or the teaming organizations. The mission concept study is expected to discuss the prime mission data analysis and interpretation plan. In all cases the PI is considered responsible for the success of the project and is recognized by NASA as the leader of the project. NASA also considers the management of cost particularly important in a PI-led mission, because the mission has been competed for on that basis. The cost cap is fixed at confirmation3 by mutual agreement between NASA and the PI. This accountability for an entire NASA mission on the part of a member of the scientific community, rather than for just a specific instrument or a specific scientific study, is what distinguishes PI-led missions from other missions.

While the primary goal of PI-led mission lines is to provide more frequent flight opportunities for important focused scientific investigations, secondary goals include the infusion of advanced technologies into PI-led missions and the involvement of the public, especially students, in the NASA mission experience.

PI-led missions stand in contrast to strategic, or “core,” missions, whose concepts are defined through NASA’s strategic planning process and are not competed for openly in the science community. Such strategic planning now generally involves the use of (1) NASA and community roadmapping exercises that identify high-priority science questions as well as the missions and technologies required to address those questions and (2) National Research Council decadal surveys, for which representatives of the astronomy and astrophysics, planetary sciences, and solar and space physics communities are convened to achieve consensus on priorities for future science research and missions in the particular discipline. Core missions, such as the Solar Terrestrial Probes4 in the Sun-Earth Connections discipline, Cassini in the solar system exploration discipline, and the great observatories (Hubble Space Telescope, Compton Gamma Ray Observatory, Chandra, and Spitzer5) in the astronomy and astrophysics disciplines, engage scientists first in mission definition and then as competitively selected instrument providers and PIs for data analysis and interpretation. NASA Headquarters and the program and project offices at NASA centers handle the top-level management for core missions. In a PI-led mission, the PI selects his or her own team, which may or may not involve NASA personnel, to manage the mission. For core missions, NASA center project management makes all budgetary and major management decisions in negotiations with NASA Program officials, allowing flexibility with respect to team membership and costs and schedules; such flexibility does not

|

3 |

Confirmation is the point in a PI-led mission at which NASA agrees to allow the mission to go forward into the final design stage (see Chapter 3). |

|

4 |

Solar Terrestrial Probes account for most of the medium-sized solar and space physics missions and are included as a mission line in NASA’s budget. See NRC, 2000, Assessment of Mission Size Trade-offs for NASA’s Earth and Space Science Missions, Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press. |

|

5 |

Great observatory missions include astronomy and astrophysics missions such as the Hubble Space Telescope, which observes in the visible spectrum; the x-ray observatory, Chandra; the infrared observatory, Spitzer; and the Compton Gamma Ray Observatory, which completed its mission and was deorbited in 2000. The missions reflect the priorities of the astronomy and astrophysics community as described in the NRC decadal surveys on astronomy and astrophysics. |

exist for cost-capped PI-led missions. The critical decision makers on core missions do not typically include members of the science team, although the latter may be consulted.

PI-led missions are conceived and promoted by smaller groups in the scientific and technical communities in order to carry out space-based measurements that are not being carried out by the agency-managed core missions.6 The science community is the chief advocate for PI-led missions, which appear in virtually every NASA roadmap and NRC decadal survey (see Appendix D). Most PI-led missions have been very successful, validating this approach to the management of small to medium-sized NASA flight projects. In spite of these benefits, however, PI-led missions, like most space missions, are not without problems. The ability of the PI-led mission selection process, which has become increasingly competitive as more concepts are proposed and reproposed, to chose projects with the greatest chance of success from among a large number of proposed missions is questionable. In addition, while straightforward on the surface, PI-led missions present special challenges to both NASA management and the proposing community. These challenges have become increasingly apparent as experience with such missions and ongoing changes in programmatic, social, and technical climates and priorities have led to a redistribution of responsibility and authority in PI-led missions and a redefinition of the processes of mission selection and implementation. For example, PI-led mission cost caps foster cost control but also contribute to marked differences in the management philosophies, practices, and pressures of core and PI-led missions. These differences, together with other factors related to mission selection, PI authority, the interactions of the PI and NASA Headquarters, and the partnering of the PI teams and centers, are addressed in this report.

The number of PI-led mission programs has continued to grow. The two newest mission lines, Mars Scout7 and New Frontiers, were spawned by a combination of scientific community advocacy8 and recognition of the potential for achieving some identified high-priority exploration goals sooner and at considerably lower cost than agency-managed core missions. The belief of former NASA Administrator Goldin in the concept also played a large part in NASA’s decision to expand PI-led mission lines.

Who proposes PI-led missions? The PI of a PI-led mission is typically a scientist affiliated with an academic institution, the aerospace industry, or a NASA center, including federally funded research and development centers (FFRDCs). The PI is responsible for defining the mission’s science goals and implementation concept (including team responsibilities and management organization of the project) within the bounds set out first in the announcement of opportunity for a PI-led mission and then in the selection notification of the mission. In addition to completing its project from spacecraft and instrument design through data interpretation within the cost-capped award, the proposing team must adhere to NASA standards and program requirements in the areas of risk management, quality assurance (QA), cost and schedule management, and reporting and review requirements. The PI may elect to share these responsibilities in consultation with a teaming organization, often a NASA center, but he or she is ultimately accountable for the mission’s success.

PI-led mission concepts are sometimes extensions of successful ground-based, airborne, suborbital, or other spacecraft investigations that have been developed over years. Concepts can also take form from studies conducted by groups of scientists and mission developers who band together for that express purpose. In either case, each PI-led mission team brings with it a different combination of management and technical experience and participating institution experience and roles. The great variety of experience and expertise among teams makes evaluation and selection of PI-led missions difficult because reviewers must weigh each team’s experience and composition for merit while comparing very different competing mission concepts. In particular, reviewers must take into account the cost caps while determining, within the limits of the information provided, the ability of the PI and proposing team to successfully complete the mission given the organization and approach they offer. On the other hand, because the PI-led approach stresses the development of an entire mission concept, through science data analysis, the selected PI team is motivated to trade effectively between science, mission design, schedule, and cost. Ideally, full mission responsibility leads to optimized mission concepts yielding the greatest scientific content and return, and technical insight enables a PI to identify and address problems early and directly. The prevailing perception is that PIs are especially able to ensure that the originally proposed science return is part of every engineering decision.

The answer to the question Why should NASA fly PI-led missions? is straightforward. NASA and the scientific community benefit from opportunities to fly missions of high scientific merit as frequently as resources permit. PI-led missions enable these opportunities because (1) they solicit mission ideas from the broadest possible community, including ideas that are not included in NASA’s long-term strategic plans, (2) they foster the formation of focused investigation teams based on the unique science and engineering skills required to achieve a particular mission’s science objectives, and (3) they encourage an efficient and minimum-cost implementation approach to a mission concept and offer the possibility of a rapid response to new discoveries. The science return for a given cost is maximized by obtaining a unique scientific data set that is made widely available to the scientific community.

The greater difficulty of implementing the proposed investigations, coupled with increasing scrutiny of the performance of all NASA missions at every stage of development and shifting ground rules, has conspired to create the occasional technical, cost, and schedule crises that spawned the call for the present study (see the Preface). In this report the committee first summarizes the basic facts about PI-led missions, from the NASA Headquarters level to the team levels, and from the AO through launch and science analysis, as determined from the information it collected. Next, the committee considers the following:

-

PI-led mission cost, schedule, and technical performance, including the reasons for cost growth,9 schedule extensions, and mission failures or cancellations when they occur.

-

The role of the PI-led mission selection process.

-

The role of management at all levels in performance.

-

Practices at the program and project10 levels that make significant differences in overall outcome.

The committee concludes with recommendations and suggestions at levels from NASA-wide and program-wide, to the level of projects and individual PIs. These recommendations and suggestions represent the committee’s best effort to respond to its charge.