2

Five Development Challenges

The Importance of Science and Technology

The committee, in consultation with senior officials at USAID, has chosen five challenges to illustrate the importance of S&T in enhancing international development and to suggest ways for USAID to draw on U.S. expertise and experience.

-

Improve child health and child survival;

-

Expand access to drinking water and sanitation;

-

Support agricultural research to help reduce hunger and poverty;

-

Promote microeconomic reforms to stimulate private sector growth and technological innovation; and

-

Prevent and respond to natural disasters.

In each of these areas USAID has active programs spanning a number of years. In most instances these programs depend on the application of findings from the natural and physical sciences and the use of information generated by the social sciences to help ensure effective program implementation.

CHILD HEALTH AND CHILD SURVIVAL

Approximately 11 million children under age five die each year, primarily in developing countries. Of these, some four million die in the first month of life. About 75 percent of the childhood deaths are the result of pneumonia, diarrheal diseases, malaria, neonatal pneumonia or sepsis, preterm delivery, or asphyxia at

birth. These problems are exacerbated by malnutrition and the lack of safe water and sanitation.1

Many of these deaths could be avoided with simple interventions, such as breast feeding, oral rehydration therapy, and immunizations. World leaders have agreed that one of the Millennium Development Goals, discussed in Chapter 1, should address this problem: “Reduce by two-thirds, between 1990 and 2015, the under-five mortality rate.”

History of USAID Involvement

USAID’s child survival agenda has been particularly active since 1985, when Congress enacted the Child Survival Program. The initial program focused on growth monitoring, immunizations, and birth spacing. The program has added new elements in response to the increased understanding of the causes of child mortality and the development of new and proven health interventions. Since that time, USAID has obligated more than $2.5 billion to child survival programs for maternal and child immunization; prevention and treatment of respiratory infections, diarrheal diseases, and malaria; breastfeeding; and nutrition and micronutrient supplementation. In addition, it has provided limited funding for clean water and sanitation, important complements to public health interventions. Annual obligations for child survival and maternal health programs have averaged about $330 million since 2001. For fiscal year 2006 the appropriation is $360 million.

Major Accomplishments of USAID and the Wider International Health Community

Health interventions based in large measure on science and technology led to a 50 percent reduction in mortality for children under five years old between 1960 and 2000. In 1960 one in five children died before age five. By 2002 this ratio had fallen to one in twelve. However, there are significant regional and local disparities; for example, in Sub-Saharan Africa, 175 in 1,000 children die as compared to 92 in 1,000 in South Asia, or 7 in 1,000 in the industrialized countries.2 The rates of decline seen in the last four decades have leveled off and, in fact, mortality rates in some Sub-Saharan Africa countries have risen between 2000 and 2002.

Malaria remains an important cause of childhood deaths in Sub-Saharan Africa. The announcement of a new Administration initiative on malaria commit-

ting $1.2 billion over five years for prevention and treatment is an important response to the problem. In October 2005, the Gates Foundation announced new grants of $260 million for development of a malaria vaccine, new drugs, and mosquito control methods.

Not only can reducing child mortality save lives, it can also help motivate parents in poor countries to limit the size of their families as they recognize the increased likelihood of their children surviving to care for them in old age. USAID has been a leader in supporting greater access to voluntary family planning services. The combination of increased child survival and greater access to family planning has slowed population increases, with fertility rates, the average number of children per woman, declining from an average of 4.97 in the period 1960-1965 to 2.79 in the period 1995-2000.

The decline in child mortality rates was accomplished largely by the use of simple, low-cost treatment and prevention tools—breast feeding; immunizations for protection against diphtheria, pertussis, and tetanus; oral rehydration therapies; and micronutrient supplements, such as vitamin A.3 USAID has played an important role in developing and promoting many of these and other lifesaving interventions and technologies to prevent and treat childhood diseases. Most experts also cite the virtual elimination of polio as another major accomplishment. Recent reports suggest, however, that new strains, originally identified in Nigeria, have led to outbreaks in Niger and in 12 previously polio-free countries. These new outbreaks demonstrate the need for continued vigilance and surveillance, not one-time solutions, in dealing with public health issues.

Continuing Challenges

USAID and the international health community have made significant progress in reducing levels of child mortality, but progress has been difficult to sustain. A more integrated approach to child health is necessary, rather than the disease-specific interventions now being used by many international health agencies, including USAID. In addition, more attention should be given to strengthening local health systems—the healthcare delivery mechanisms and healthcare workers responsible for transferring the results of new scientific discoveries and technologies into improved health outcomes. The situation is particularly severe in Sub-Saharan Africa, where healthcare systems have been battered by the effects of HIV/AIDS. Many of these systems have lost healthcare workers to AIDS; and the demand on existing workers to provide treatment and palliative care for AIDS patients has diverted attention from primary healthcare needs, including the needs of children and pregnant women.

Continued implementation of proven approaches to the prevention of childhood diseases and to prenatal and neonatal health services is essential. For example, more than 30 percent of the world’s children have not received basic immunizations against the six common childhood diseases. Currently more than 500,000 women worldwide die each year from complications of pregnancy and childbirth. More than 4 million newborns die and 4 million more are stillborn each year across the globe. Ninety-nine percent of these deaths occur in developing countries. In response, USAID has embarked on a major new maternal- and newborn-health initiative. The program builds on its activities in neonatal health, prevention of hemorrhaging in childbirth, and other birth-related complications.

USAID’s past investments in health research, in particular those focused on reducing child mortality, have led to important improvements in public health. However, the advent of major new sources of research funding and the expansion of a number of research centers to include a focus on diseases typically found in developing countries require USAID to reexamine where its limited resources can be used most effectively. The agency’s extensive experience in assessing local health conditions and in adapting health interventions to local social and cultural conditions, and its strong relations with local government agencies and research organizations, suggest that its resources should be focused primarily on helping to identify and prioritize local health needs. USAID should also support the adaptation, field testing, and implementation of improved health interventions, while assisting in strengthening local health systems as discussed in Chapter 3.

USAID has collaborated in numerous research efforts on vaccines for malaria, Haemophilus influenzae type B (Hib), rotavirus, and Streptococcus pneumoniae with other federal agencies, WHO, private pharmaceutical companies, and international research organizations. Much work has been in progress for many years. The National Institutes of Health and major foundations, such as the Gates Foundation, have begun providing significant support for vaccine development, and USAID has scaled back its research accordingly.

SAFE WATER

More than one billion people do not have access to adequate supplies of clean, safe water. More than 2.5 billion people, representing about 40 percent of the world’s population, are without appropriate sanitation.4 As a result, almost 4,000 children die every day.5 Many more become ill from waterborne diseases, including cholera, typhoid, schistosomiasis, and diarrheal diseases.

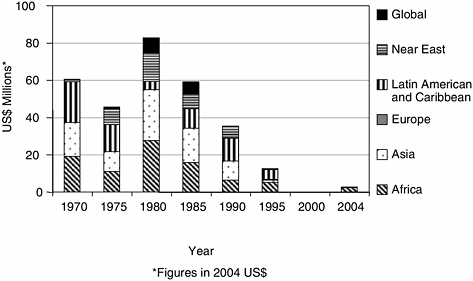

FIGURE 2-1 Population without improved water sources or sanitation by region, 2002.

SOURCE: “Water Supply and Sanitation Monitoring.” World Health Organization. http://who.int-water_sanitationhealth/monitoring/mp04_3pdf.

As seen in Figure 2-1, access to clean water varies dramatically. Less than 60 percent of the population in Sub-Saharan Africa has access to improved drinking water sources6 compared to almost 90 percent in Latin America and the Caribbean and almost 100 percent in industrialized countries. Improving access to water and sanitation often depends on the deployment of conventional engineering technologies, but in other cases less costly, innovative technologies can be used, such as point-of-use treatment and storage systems, membrane technologies, household water treatment, and dry sanitation and ecological sanitation systems.

Progress to Date

Between 1990 and 2002 more than 1.1 billion people gained access to safe water, with the greatest progress in South Asia. Despite substantial gains in coverage that averaged 90 million people a year, the number of people without access to safe water has declined by only 10 million because of population growth.

During the same period, worldwide sanitation coverage increased from 49 percent to 58 percent of the world’s population. However, less than 50 percent of the people living in developing countries currently have access to rudimentary sanitation. The situation is particularly severe in the informal settlements around urban areas where untreated human wastes contaminate water supplies and the environment.

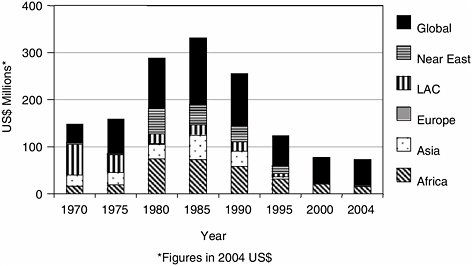

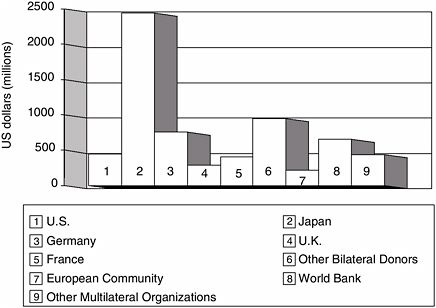

At the Millennium Summit in 2000, world leaders pledged to cut the proportion of people without safe drinking water by half by 2015. At the World Summit on Sustainable Development in 2002, leaders also agreed to reduce by half the proportion without access to adequate sanitation by 2015. International aid for water supply and sanitation approached $7 billion over a recent five-year period, as seen in Figure 2-2.

History of USAID Involvement

USAID has supported drinking water and sanitation projects for more than three decades.7 In the 1990s there was increasing emphasis on drinking water projects that could contribute to the agency’s child survival programs. The agency also carried out and continues to carry out complementary projects on watershed management, coastal zone management, and industrial pollution control, all of which affect water availability and water quality. The effectiveness of these

FIGURE 2-2 Average annual aid for water supply and sanitation by donor, 1996-2001. SOURCE: Gleick, Peter H. “The Millennium Development Goals for Water. http://www.pacinst.org/topics/water_and_sustainability/global_water_crisis/

projects depends on having strong internal technical staff trained in engineering, hydrology, ecology, and related areas that can develop program interventions, select appropriate contractors, and monitor program implementation.

USAID obligations for water supply, sanitation, and wastewater management were about $220 million in 2000. Of this, three-quarters was spent on projects in Egypt, the West Bank, Gaza, and Jordan. Of the $80 million obligated for drinking water supply, only $1.4 million went to support projects in Africa,8 the region with the greatest need.

At the 2002 World Summit on Sustainable Development, the Administration announced a major new initiative, “Water for the Poor,” to support the Millennium Development Goal of increasing access to water and sanitation. In 2005 USAID reported on the “success” of the initiative by noting that over 9.5 million people now have better access to water and 11.5 million people have access to adequate sanitation because of the initiative, which has provided $970 million in over 70 countries.9 The geographic pattern of USAID obligations for water and

sanitation, however, is not much different today than before the summit. In 2005 USAID reported plans to obligate about $7.7 million for drinking water projects in Africa, with an estimated $111 million for worldwide efforts. The total figure, no doubt, is a low estimate since it does not take into account any supplemental funds earmarked for restoration and reconstruction of drinking water and sanitation facilities in Afghanistan and Iraq.10

For more than 20 years the agency provided funds for a series of environmental health activities, including water and sanitation. The last of these programs, the Environmental Health Program (EHP), terminated in the fall of 2004 and was replaced by the Hygiene Improvement Project. One element of the EHP focused on providing environmental services—drinking water, sanitation, and waste collection—to residents of urban slum communities in India. The committee’s panel that visited India was impressed with the capabilities of the Indian staff on the project and the technical backstopping provided by the USAID mission. The program seems to have been quite effective and could be a model for other programs to address the needs of slum dwellers. An important element was its focus on disseminating results and in providing information, including assessments of alternative household water treatment technologies, to NGOs and other organizations concerned with environmental health.

USAID continues to provide substantial funding for the provision of drinking water and sanitation facilities in response to natural disasters. The response to the South Asian tsunami is the most recent example. In this case a new water treatment facility was put into operation in Banda Aceh within six weeks of the disaster. The plant produces over 400,000 liters of drinking water a day, which is being distributed to thousands of people, many in refugee camps. The quality of the water is reportedly equivalent to bottled water, exceeding EPA and WHO standards.

Following Hurricane Mitch in Central America, USAID asked EPA to help with rehabilitation of drinking water treatment facilities. The program focused on enhancing the technical capacity of the water utilities and ministries of health. It included strengthening laboratory capacity, improving water treatment plants, enhancing source water protection, and training for staff responsible for managing drinking water programs. An evaluation of the program suggested that a number of short-term goals were achieved, but a longer-term effort is needed to integrate source water protection and safe drinking water components into existing local water quality programs. This longer-term view is clearly critical to ensuring an expanded availability and access to water as well as sanitation. The evaluation also highlighted the need for strong local regulatory frameworks and improvements in local technical skills. Again, both issues require long-term investments.

Challenges and Opportunities for USAID

USAID has a very limited staff—less than a half-dozen personnel—with the technical skills to support its water and sanitation programs. The agency relies to a great extent on major U.S. engineering firms to design and manage its large-scale programs in the Middle East, including those in Iraq and Afghanistan. With little technical field staff, the agency’s detailed knowledge of progress (and problems) on the ground is limited.

In Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union, USAID has drawn on the skills of EPA to upgrade water treatment plants. It has also had an effective partnership with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to create innovative point-of-use treatment technology to provide safe water for household use. In addition, the agency created a partnership through the Global Development Alliance with Proctor and Gamble to develop another point-of-use treatment technology. These relatively inexpensive technologies provide safe water in the absence of local large-scale drinking water treatment plants.

Important members of Congress support an expansion of USAID’s water and sanitation efforts. A number of advocacy groups are also encouraging Congress to earmark more substantial funding for these activities. The fiscal year 2006 appropriation includes an earmark of $200 million for drinking water supply projects and related activities. The Senator Paul Simon Water for the Poor Act of 2005 mandates access to safe water and sanitation as a policy objective of U.S. foreign assistance.11 Highly visible water projects will continue to be a focus of congressional attention and should foster goodwill abroad.

USAID will undoubtedly continue to invest in water and sanitation facilities, with most of its funding directed to large-scale reconstruction and upgrading efforts in Iraq and Afghanistan. Access to drinking water and sanitation in other countries to complement health interventions and to support the Millennium Development Goals will also continue to interest Congress. USAID needs adequate technical staff both in the field and in headquarters to oversee these programs and to assess the numerous innovative technologies now available—for providing both drinking water and sanitation services—that can be matched to local needs, financial resources, and cultural sensitivities.

AGRICULTURAL RESEARCH TO REDUCE HUNGER AND POVERTY

For many countries, agriculture is the foundation for development. In developing countries agriculture contributes about 25 percent of the gross national product and employs about 55 percent of the labor force. Agriculture contributes to economic growth by providing food and raw materials, generating foreign

exchange, and creating jobs on the farms and in processing and distribution. During the last 30 years, dramatic increases in agricultural productivity, largely as a result of the introduction of new varieties of rice and wheat, have expanded world food supplies. Despite these increases, however, food supplies in many parts of the developing world are inadequate.

The Food and Agriculture Organization estimates that in 2002 over 850 million people worldwide had inadequate food supplies.12 Although this represents a slight decrease since 1996, it is far short of the goal set at the World Food Summit, where commitments were made to reduce the number of malnourished to 400 million by 2015. The problem is most serious in Sub-Saharan Africa where an estimated 33 percent of the population remains undernourished, just 1 percent less than in the period 1969-1971. By contrast, the percent of the population that was undernourished in East and South Asia declined from 43 percent of the population to 10 percent during the same period.

With expected increases in world population growth over the next half century, global food supplies must double to produce enough to meet the demand. One-half of the projected increase in demand comes from population growth, which is estimated to reach 9 billion, and the other one-half from income growth.

An estimated 75 percent of the very poor live in rural areas and depend on agriculture and natural resources for their livelihoods. Long-term reduction in poverty and prospects for sustained economic growth will depend on improvements in the productivity of rural areas. These improvements will depend on the development and application of new agricultural technologies, including those based on biotechnology, improved pest management, and better natural resource management.

History of USAID Involvement

USAID and its predecessor agencies have supported agriculture since the 1950s, initially emphasizing the transfer of U.S. agricultural technologies to poor countries, using U.S. agriculture extension services as a model. However, many U.S. technologies were not appropriate to the local needs of developing countries. In the 1960s and 1970s, USAID, other donors, and private foundations began to fund the development of more appropriate technologies and strategies.

With initial support from the Ford Foundation and the Rockefeller Foundation, the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR) was established in 1971.13 As of 2005 CGIAR supported 15 research centers.

|

12 |

Food and Agriculture Organization. Assessment of the World Food Security Situation. FAO Committee on World Food Security. 31st session. May 23-26, 2005. Available at http://www.fao.org/docrep/meeting/009/J4968e/j4968e00.htm. Date accessed June 22, 2005. |

|

13 |

Over the years it has received $5.5 billion from the international community. The United States has been one of the largest donors, contributing almost $50 million at its highest annual level in 1986 and about $26 million in 2005.

In 1975 new provisions were added to the Foreign Assistance Act to provide program support for long-term collaborative U.S. university research on food production and distribution, storage, marketing, and consumption and for creation of the Board on International Food and Agricultural Development (BIFAD). The programs were designed to take account of the value of such programs both to U.S. agriculture and to developing nations. The university-based activities subsequently became known as the Collaborative Research Support Program (CRSP).

Currently, nine CRSP programs are funded through grants and cooperative agreements. Eight universities serve as management entities, with many additional universities participating. Leading American agricultural scientists recognize the importance of working on problems confronting the developing countries in order to broaden their scientific horizons. Many scientists are interested in participating even if they are reimbursed only for travel expenses. At the same time, the CRSP program should be driven by the interests and needs of the developing countries with the American specialists supporting these interests.

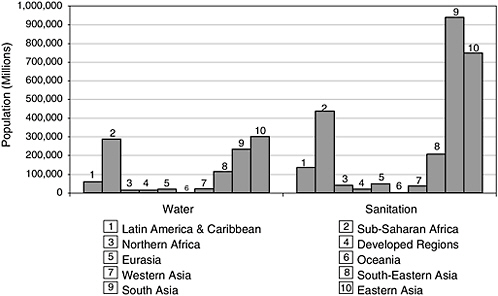

During the 1970s and 1980s, USAID also expanded support for national agricultural research systems. However, since the late 1980s funding for local research institutions has declined dramatically. Total USAID funding for agriculture has fallen from over $2 billion in 1985 to $400 million in 2003, and the current fiscal year 2006 budget request shows only $316 million in development assistance funding for all agriculture and environment activities,14 as seen in Figure 2-3. The focus has changed from programs designed to improve smallholder incomes to increased production and processing of agricultural crops for export markets and to biodiversity conservation and management of protected areas. This decline is surprising given USAID’s long history of successful agriculture programs.

The reductions in USAID support for agricultural research has paralleled reductions by other donors. Total support for the CGIAR system declined almost 2 percent a year between 1992 and 2001, and contributions are increasingly restricted to special interest programs. A long-term view of funding for agricultural research by USAID is given in Figure 2-4.

In summary, overall donor support for all agricultural programs in developing countries reached a high of about $9 billion annually in the early 1980s (at 1999 prices), falling to less than $5 billion in 1997 and under $4 billion in 2001.

The share of agriculture in overall aid budgets worldwide is now about 6 percent, considerably less than the 17 percent share reached in the early 1980s.15

The Millennium Challenge Corporation also offers a source of funding for agriculture-related projects and the initial compacts have included funding for irrigation, land tenure, agribusiness development, and general rural development. Furthermore, funding from the World Bank for agriculture has more than doubled in the last five years.

In part, the general decline in funding for agriculture may have resulted from increases in world food stocks and low prices in many parts of the world. The agricultural research that focused on germplasm improvement has been unpopular in some key donor countries,16 and there has been an increasing level of concern expressed about the potential environmental effects of changes in farming systems accompanying the Green Revolution. Some of these concerns relate to loss of local control over farming systems, control that is viewed to be integral to cultural integrity. Other concerns relate to the potential for loss of control of agriculture to commercial interests, such as multinational seed and fertilizer companies. The issue of loss of genetic diversity and control over indigenous germplasm and related intellectual property is another issue frequently cited. The decline may also reflect increasing concerns in the United States and elsewhere of increased international competition from agricultural exports of developing countries.

Challenges for the International Donor Community

Continued investments in agricultural R&D are critical if world food supplies are to increase and prospects for reducing rural poverty are to improve. The global landscape for agricultural R&D has changed dramatically in the last two decades. Increasing globalization has resulted in substantial increases in trade in agricultural commodities as well as the internationalization of agricultural research. The types of institutions conducting agricultural R&D, the sources and levels of funding, and the kinds of research, technologies, and delivery systems needed now are significantly different than in the 1960s, when the international development community began to focus on agricultural S&T.

At the same time that the international donor community reduced its funding for agricultural R&D, most developing countries also reduced their support for agricultural research; for example, in Bangladesh, the Minister of Agriculture reported that the budget had declined from 22 percent to less than 3 percent of the national budget. In Mali, government funding for the agricultural research system

has been slashed; and a 10-year hiring freeze has been imposed within the Ministry of Agriculture.

Despite international commitments for reducing hunger, programs of many donors in the agricultural sector, including USAID, stress exports over growing of basic food crops. In Mali, for example, scant attention is paid to dry-land small-holder farming of millet and sorghum. Rather, communities with rice or cotton potential receive the most attention. But 90 percent of the population depends on dry-land agriculture. This development is dismaying, given the link between hunger and agriculture.

Finally, USAID has been at the forefront of gender issues in agriculture. Women participate in the selection and cultivation of crops. They are marketers of agricultural products throughout Africa and in much of Latin America. They play an important role in using their income to improve health and sanitary conditions at the grassroots level.

Unique Challenges and Opportunities for USAID

As noted above, the level of USAID funding for agriculture, and particularly for agricultural research in developing country institutions, has declined substantially in recent years. At the same time, Congressional directives and earmarks have required the agency to maintain its levels of support for a number of activities, such as the CRSP programs ($28 million) and the International Fertilizer Development Center ($2 million). These earmarks combined with declining overall budgets for agriculture restrict the agency’s ability to respond effectively to new opportunities; for example, there is growing recognition of the use of high-value horticultural crops in development programs. They provide essential micronutrients, they can be produced in relatively small areas, and they are a source of income for rural families. Conventional breeding and genomics are providing new varieties of vegetables and fruits with disease and insect resistance, improved nutrition, and adaptability. All of these developments are of great interest to developing nations.

The increased emphasis on short-term results has also made it difficult to provide some of the types of assistance most needed—strengthening local and regional research centers, training local scientific and technical personnel to focus on local agricultural problems, and providing extension services to farmers and others who are involved in the production, processing, and marketing of agricultural products.

In July 2004 the agency released a new agriculture strategy “Linking Producers to Markets,” which focuses on the following major objectives:

-

Expand trade opportunities and improve the trade capacity of producers and rural industries;

-

Improve the social, economic, and environmental sustainability of agriculture;

-

Mobilize science and technology and foster a capacity for innovation; and

-

Strengthen agricultural training and education, outreach, and adaptive research.

The emphasis in the strategy on the role of S&T is welcome, particularly the discussion of the increasing importance of biotechnology and information and communications technologies in increasing agricultural productivity and marketing.17

The agency’s staff with technical expertise in agriculture has declined significantly from 185 agricultural scientists and agricultural economists in 1985 to 48 in 2005.18 As a result, mission backstopping, interactions with technical counterparts at the local level, and collaboration with important U.S.-based experts have been increasingly left to contractors. While contractors have many strengths, they often do not have the long-term commitment to the larger-scale agency objectives.

University partnerships, long the basis for USAID’s agricultural efforts, have suffered as a result of a new emphasis on short-term results, the decline in long-term training and other capacity-building efforts, and the lack of effective interlocutors from USAID.

Many of the existing institutional arrangements for the provision of agricultural science and technology in developing countries have been effective, but these mechanisms should be reassessed as to their ability to meet current needs. USAID’s own internal reviews of the CRSP system, in fact, have recommended such a review. Meanwhile, a long-term international effort is underway to examine the international agricultural research systems, and USAID is completing a desktop review of agriculture and natural resources management research priorities (see Appendix G).19 The results of these reviews should be used to better focus USAID’s agricultural S&T investments and to ensure that such investments meet the needs of client countries for providing adequate food supplies and promoting economic growth. USAID’s agricultural programs should not be allowed to languish.

MICRO-ECONOMIC REFORM

The private sector (e.g., farmers, cooperatives, micro enterprises, local manufacturers, and multinational corporations) currently provides more than 90 percent of the jobs in developing countries.20 Donor assistance to the private sector traditionally has focused on direct support to private sector enterprises and encouragement of macro-economic reforms, but improving the overall investment climate for both domestic and foreign private firms also requires micro-economic reforms. This section addresses such reforms without in any way seeking to diminish the importance of effective economic policies across a wide array of areas, including macro-economics, trade, and investment.

According to USAID, these micro-economic reforms include “improvements in regulations and other policy changes that directly impact the business and investment environment within which a firm operates. The development and enforcement of business regulations can influence the ability of firms to access credit, hire and fire employees, enforce contracts, own property, register their business, process goods through customs, meet standards, protect intellectual property, pay taxes, and carry out a myriad of other everyday activities directly affecting firm efficiency and productivity.”21

Recent research suggests that business regulations are often the most important factors influencing decisions on locating, operating, and expanding firms.22 Improvements in the business environment create profit opportunities by lowering transaction costs, reducing risks, and increasing competitiveness. It is then easier for firms to respond to changes in demand in both global and local markets. Firms find it easier to innovate, whether by adopting widely available technologies, adapting existing technologies to local needs and supplies, or developing new technologies—including new hardware and more efficient production and distribution processes.

Studies suggest that more than 80 percent of the variation of gross domestic product per capita across countries is accounted for by different levels of development of microeconomic fundamentals and that improvements in the business environment can have a significant positive effect on growth.23 The World Bank’s report “Doing Business in 2005: Removing Obstacles to Growth” estimates that

|

20 |

World Bank. World Development Report 2005: A Better Investment Climate for Everyone. Washington, DC: World Bank, September 2004. |

|

21 |

USAID. USAID and Microeconomic Reform Project Profiles. Washington, DC: USAID, June 2004. |

|

22 |

Background paper by Michael Porter, Building the Microeconomic Foundations of Prosperity: Findings from the Microeconomic Competitiveness Index. www/isc.hbs.edu/pdf/GCR_0203_mci.pdf, accessed July 14, 2005. |

|

23 |

S. Djankov, C. McLiesh, and R. Ramalho. Regulation and Growth. Washington, DC: World Bank, March 2005. |

for some countries improvements in the ease of doing business can add 2.2 percentage points to annual economic growth.

Activities of USAID and Other Donors

Over the past two decades, USAID and other donors have supported initiatives to stimulate private sector growth. The bulk of the assistance, which is estimated to be about $20 billion a year, or 26 percent of development assistance,24 has been for infrastructure development, policy support, and technical assistance. Approximately one-third of this assistance has been directed to improvements in the investment climate. The focus of these activities has shifted since the 1980s, when the main emphasis was on macro-economic stability, reducing pricing and exchange rate controls, reforming public enterprise, and liberalizing the financial sector. As noted above, economic research by the World Bank and others showed the importance also of micro-economic and institutional reform as a means of improving the business environment and supporting global integration.

On a multilateral level, USAID has worked on micro-economic reform issues with the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development’s Development Assistance Committee, the G-8, the World Bank, and the World Economic Forum. The new OECD Network on Poverty Reduction is central to these activities and provides an effective forum for coordinating donor efforts.

At the 2004 G-8 Summit, government leaders agreed on actions to promote private sector development, including actions to improve the business climate for entrepreneurs and investors. These include working with the multilateral development banks to support coordinated country-specific action plans to address key impediments to business, and to develop pilot projects to facilitate comprehensive reform programs.

USAID is providing financial support for two benchmarking activities: the World Bank’s Doing Business Project and the World Economic Forum’s Global Competitive Index. The Doing Business Project reports on the costs of doing business in more than 130 countries.25 The indicators are useful for examining where reforms are needed and for identifying where and why reforms have worked. For example, the 2005 report says that only two procedures are needed to start a business in Australia, but 19 are required in Chad. In each of the countries covered the World Economic Forum’s Business Competitiveness Index evaluates the underlying microeconomic conditions: “the sophistication of the

operating practices and strategies of companies and the quality of the microeconomic business environment.”

A recent survey of USAID activities related to micro-economic reform indicates that more than 600 activities have been supported since 1990. Many programs have been in Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union, where political and economic changes have required entirely new business models.26 Activities have included development of tools for contract enforcement and dispute resolution, assistance in drafting labor regulations, and provision of equity financing for business.

In Latin America technical support for micro-economic reform began in the late 1980s with a program to identify and eliminate constraints on private sector investment in Bolivia. Fewer micro-economic reform activities have been carried out in Africa than in other regions, but some USAID missions are planning micro-economic activities to support expanded trade. Such regulations include the adoption of sanitary and phytosanitary standards.

Challenges and Opportunities

USAID is increasing its focus on micro-economic reform. Of course, the agency has a long history of support for economic research that could be used as the basis for many of its policy reform efforts as well as a broader understanding of development issues. In the case of micro-economic reform there is good evidence of the long-term effects of such changes on economic growth. However, continued support for such reforms will be challenging, requiring staff with economic skills to monitor activities, conduct assessments and research, and carry out evaluations.

A one-size-fits-all approach is not appropriate for micro-economic reform. Priorities must be consistent with local conditions—current regulatory costs and opportunities for improvements need to be identified. Once initial reforms have been made, they must be monitored and enforced. In addition, regulatory systems constantly need to be examined and adjusted in response to changing local and global conditions.

Recent initiatives to link increases in foreign assistance through the U.S Millennium Challenge Account and the World Bank’s Fast Track Initiative to quantifiable reform targets should provide incentives for change. The availability of country-level data comparing the business climate also provides incentive for change.

USAID’s ability to participate in these new opportunities is limited by the lack of technical staff and qualified contractors. The agency currently has an

inadequate evaluation capability and limited economic research expertise. USAID has only one specialist in Washington working on micro-economic reform issues, and missions have little capability. USAID can draw on contractor support for some activities, but there are few firms with relevant experience. In the past, USAID had a strong staff of highly qualified economists, directly linked to senior policy makers. This is no longer the case, and USAID is less able to influence economic policies that would allow S&T interventions to have a more substantial impact on long-term development.

Of particular concern is USAID’s current lack of a strong evaluation capability and process for disseminating information on its micro-economic reform efforts. A study by Development Alternatives, Inc. found that the internal evaluation system collapsed in the mid-1990s.27 Documentation on USAID private sector support activities had been lost. Being able to document and conduct analyses of micro-economic reform interventions and the results of such interventions seems essential.

NATURAL DISASTERS

The Indian Ocean tsunami dramatically demonstrated the immense vulnerability to natural disasters of millions of people in developing countries. More than 280,000 lives were lost; and millions more lost homes, family members, and their traditional sources of income. As in other cases of natural disasters, the international community responded, pledging billions of dollars for relief efforts and mounting reconstruction programs in every country affected by the disaster. The tsunami was just one recent reminder of the consequences of natural disasters on development prospects. The more recent earthquake in Pakistan is another.

An estimated 75 percent of the world’s population lives in areas that have been affected at least once during the last two decades by floods, drought, hurricanes, earthquakes, or cyclones. During the same period, more than 1.5 million people were killed by such disasters. An estimated 85 percent of the population at risk live in developing countries and accounted for more than 98 percent of the deaths.

The economic losses associated with disasters are enormous—estimated at more than $650 billion annually in the 1990s compared to about $215 billion in the 1980s and $140 billion in the 1970s. A large portion of the losses occurred in developed countries, but these countries generally have systems in place to minimize loss of life (early warning systems, for example). In addition, they have access to immediate emergency and medical care as well as insurance programs to cover some property losses. In developing countries natural disasters are more

likely to result in significant casualties, economic and social development disruption, and diversion of funds from development to emergency relief and recovery programs. Statistics compiled by the World Bank show that in recent years natural disasters reduced annual gross domestic product (GDP) in Nicaragua by more than 15 percent, in Jamaica by 13 percent, and in Bangladesh by more than 5 percent. In Honduras, Hurricane Mitch caused losses of 40 percent of GDP, about three times the government’s annual budget.

History of USAID Involvement

The USAID Office of Foreign Disaster Assistance (OFDA) was created in 1964 to provide a central locus for managing U.S. government foreign disaster assistance. Two major disasters in 1963—a volcanic eruption in Costa Rica and an earthquake in Skopje—prompted the creation of the new office.

Between 1964 and 1990, OFDA responded to more than 1,100 disasters. It provided more than $300 million in International Disaster Assistance (IDA) contingency funds and catalyzed almost $5 billion in other U.S. government funds. Between 1990 and 2000, OFDA provided $45 million annually in responding to almost 700 disasters. Floods were the most frequent form of disaster, followed by disasters involving civil strife and complex humanitarian emergencies. While the committee has focused on natural disasters,28 it is important to recognize that addressing problems created by complex humanitarian emergencies is a large part of the work of OFDA. Increasingly, remote sensing, aerial photography, and other technologies are being used to help respond to such humanitarian crises. In fiscal year 2005 OFDA responded to 17 complex humanitarian emergencies in Iraq, Sudan, Liberia, Afghanistan, Angola, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Indonesia, and other countries, spending more than $240 million.

For more than 25 years S&T have played an important role in OFDA programs, as OFDA developed early warning systems, improved communications systems, and mounted disaster mitigation and response programs. In 1978 the National Academy of Sciences prepared two reports for USAID, exploring the role that S&T could play in strengthening the office’s programs. One focused on general management issues and the other more specifically on the role of technology in disaster assistance programs. See Box 2-1 for selected recommendations from the report The U.S. Government Foreign Disaster Assistance Program. Several of these recommendations are equally applicable today.

In the late 1980s OFDA and USAID’s Africa Bureau developed FEWS NET, a famine early warning system allowing for the exchange of water informa-

|

BOX 2-1

SOURCE: National Research Council. The U.S. Government Foreign Disaster Assistance Program. Washington, D.C.: July, 1978. |

tion and climate monitoring and reporting on hydro-meteorological developments likely to affect food supply, including cyclical droughts and flooding. In Asia, OFDA has worked with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration using seasonal climate forecasts to cope with the effects of the 1997-1998 El Niño/Southern Oscillation. OFDA has supported a number of flood-monitoring programs in Asia, including community programs in Bangladesh, designed to reduce the vulnerability of people living in flood plains. OFDA has also provided funding for the U.S. Geological Survey’s Volcano Disaster Assistance Program, which provides technical assistance to volcano-monitoring organizations around the world.

OFDA has been able to make effective use of relevant S&T resources not only from other U.S. government agencies but also from U.S.-based and international organizations. Increasingly OFDA has been able to draw on the resources of the Department of Defense to assist with immediate logistical support for disaster response. In addition, OFDA has special authority to expedite contracts for disaster response services.

Continuing Challenges and Opportunities

It is expected that the frequency and cost of natural disasters will increase in the coming decades—the result of environmental degradation, climate change, and population growth in cities and vulnerable coastal areas. These costs will occur not only in developing countries but also in the United States and other developed countries. The enormous economic and social costs caused by Hurricane Katrina revealed the vulnerability of U.S. coastal communities. Many rapidly growing urban areas in developing countries are similarly vulnerable to natural disasters as large proportions of the population live in unauthorized settlements in ecologically stressed areas.

In many countries disaster prevention and preparedness programs tend to lose out to other seemingly more immediate political priorities. Even within OFDA, prevention and mitigation programs receive only a very small percentage of the overall budget—about 10 percent—with most of the office’s funding used for disaster response. Recent experience suggests that more attention should be paid to assisting countries in prevention and mitigation efforts. Furthermore, USAID’s mainstream development activities generally do not include hazard mitigation activities even in the aftermath of a disaster. This disconnect between disaster response programs and long-term development efforts (for example, coastal zone management) deserves increased attention.

In OFDA, as in other parts of the agency, constraints on hiring technical staff are a problem. OFDA has attempted to deal with this by using a variety of mechanisms to borrow staff from other organizations. Only about 10 percent of the OFDA staff consists of direct-hire employees, which hampers the office’s ability to influence other offices within the agency and to represent USAID to other organizations. This representation function is more important in the wake of Hurricane Katrina, as other organizations involved in disasters strengthen their staffs.

Crosscutting S&T Issues

Information and communications technology (ICT) is a critical crosscutting issue that affects a wide variety of programs in such areas as agriculture, health care, education, small business, democracy, and trade expansion. A recent survey of USAID missions indicates that 95 percent of the missions support some ICT activities, many associated with democracy, governance, or education programs. In a number of instances USAID also provides support for regulations governing ICT infrastructure, training of technicians, and ICT hardware. For example, in Africa, the Leland Initiative helped to establish policy and regulatory regimes and to support local Internet service providers. Working with Cisco Systems Inc., USAID has provided training for ICT technicians in more than 30 countries.

Turning to education, meeting the challenges discussed above requires spe-

cialists with strong scientific, technical, and engineering skills. For the most part, the committee focused on training at the university and graduate levels and strengthening of local and regional S&T institutions. Equally important, however, is the provision of science education at the primary and secondary levels. For many people, especially in Africa, this will be their only opportunity to become scientifically literate, begin to become independent thinkers, and learn critical problem-solving skills. These tools are essential in adjusting to changing labor markets, adapting and using modern technologies, and being effective participants in civil society. Good basic science and basic mathematics programs at the elementary and secondary school level also stimulate students to pursue careers in a variety of scientific disciplines.

Currently a large portion of USAID’s education budget is allocated to primary education, but science education seems to be of little concern in these programs. One exception is a project to bring science and mathematics teachers from South Africa to the United States for leadership training. Clearly, the U.S. S&T education community could provide greater inputs to USAID’s primary and secondary education programs.