Panel IV

Moving Offshore: The Software Labor Force and the U.S. Economy

INTRODUCTION

Mark B. Myers

The Wharton School

University of Pennsylvania

Opening the session, Dr. Myers called the attention of the audience to the absence of economists on this panel, which was to address the timely topic of offshore outsourcing. Its speakers, he noted, represented the business and policy communities. He then proceeded to introduce Wayne Rosing of Google, who in his long experience in Silicon Valley had traversed many prominent companies, among them Caere Corporation, Sun Microsystems, and Apple Computer.

HIRING SOFTWARE TALENT

Wayne Rosing

Dr. Rosing took the occasion to present some facts about Google in hopes of dispelling what he alleged to be myths that had grown up around the company

during its nearly 6 years of existence. About 40 percent of the company’s 1,000-plus employees were software engineers, a figure it wanted to increase to 50 percent; 7 of 11 executive-staff members were engineers or computer scientists, a reflection of Google’s identity as an engineering company. Talk of finance and other business topics tended to be crowded out of meetings of the executive staff by its members’ focus on “designing things.”

Dr. Rosing named four keys to the success that Google had enjoyed to date:

-

a brilliant idea—an algorithm called Page Rank that created a better way to organize, rank, and rate sites on the Web—which had been conceived by two Stanford students and out of which had come a better search engine;

-

a motivating mission statement, which put forth as the company’s aim organizing and presenting all the world’s information and trying to make it universally accessible and usable. “That’s one of the few corporate mission statements that I believe is actually realizable in, maybe, the next decade,” declared Dr. Rosing, who underscored his use of the word “all” in qualifying “the world’s information;”

-

a business model fueling an extraordinary level of reinvestment in the business, which was very capital intensive, owning large numbers of computers; and

-

a practice of hiring large numbers of engineers—“a feedback loop that we keep pushing on.”

Dr. Rosing launched his discussion of the panel’s topic, which he reformulated as “selective hiring,” by stating that Google was “working on some of the hardest problems in computer science” in search of its “Holy Grail[:] … that, someday, anyone will be able to ask a question of Google, and we’ll give a definitive answer with a great deal of background to back up that answer.” This vision, whose fulfillment the company was not predicting for the near future, was carrying it far beyond the technical problem of searching Web pages. In its pursuit, Google had designed and built, and was running, what it believed to be the world’s largest distributed computer. At the time of the conference, Google was beginning what was essentially the fourth rewrite of its code, which was constantly being rewritten. The company had two basic hunks of code: (1) Google.com, the familiar search engine, and (2) a set of code for its advertising system and monetization. The company kept the two separate because it had a policy of not selling the ability to get into its index; Google robots had to find a site or information, which was then ranked algorithmically. Employees working on these two code bases were kept apart as well, although they did at times need to interact.

“The Best Minds on the Planet”

The task on which Google was embarked was too difficult to outsource, said Dr. Rosing, adding, “Rather, what we need to do is to pull together all the best

minds on the planet and get them working on these problems.” Unlike the task itself, attracting the world’s best minds to Google was “very simple.” In 2003, the company had received a total of 35,000 resumes. As a first step they were culled, mainly by Google engineers but with some recruiters also taking part. From a pool made up of those whose resumes had been selected and prospects who had been referred by employees, the company screened 2,800 applicants. Of those, about 900 were invited to interview, and from that set Google hired around 300, about 35 percent of whom were from the group referred by employees. While the vast majority of Google’s employees had graduate degrees from U.S. institutions, they hailed from all over the world, a fact reflected in the makeup of the group of new hires. “So you hire good people,” Dr. Rosing observed, and “they know other good people. That’s the best source of people.”

Of the qualities sought by the company in its hires, Dr. Rosing placed “raw intelligence” first; applicants were likely to be asked their SAT scores, a practice not necessarily common in the corporate world. Second, he named strong computer-science algorithm skills, evidence of which was a degree in computer science from Stanford or the University of California at Berkeley with a superior grade-point average. Google also looked for very well developed engineering skills, as indicated by an applicant having written a program on the order of 10,000 lines in length. “Culture fit” was considered highly important as well, because Google had very little management; 18 months before, Dr. Rosing said, the company had had more than 200 software engineers, and all had worked for him. Really good people, he stated, do not need to be managed, they just need to be given clear goals.

Workers Needed Around the Globe

Google’s outstanding problem, Dr. Rosing lamented, was that “there just aren’t enough good people.” Too few qualified computer science graduates were coming out of schools in North America, including the United States, and in Europe. Short term there was no limit on how many engineers Google was prepared to hire as long as they measured up—and if they could be found. Additionally, pointing out that broadband and other technologies were being deployed faster in many other countries than they were in the United States, he noted that Google’s business required having capable employees around the world. Language-specific software skills and, in many cases, a high degree of cultural sensitivity were necessary. The company had begun to hire people abroad, and those people were needed in their own cultures, so it was not practical to bring them to the United States.

Raising a related issue, Dr. Rosing said that Google’s in-house immigration specialist had written a memo only days before stating that the H-1B visa quota for the current fiscal year had been filled. Instead of the approximately 225,000 H-1B visas that had been authorized for prior years, the number had been capped

at 65,000 in fiscal year 2004—which, he remarked, was an election year. Unable for this reason to hire some people it had in its pipeline to work domestically, Google was opening engineering offices outside the country where foreign employees could be placed after they had been educated, “presumably at taxpayer expense,” in the United States. “Now I must ask, why [is this country] doing this?” he said. Google had “smart people, global reach, and scope; and … we’re intellectually intensive, we’re consumed with aggressive reinvention, and we try to automate to the limit to maximize the gross margin per employee.” It was, in fact, an example of the type of company that the New Economy was supposed to produce and that would fuel the growth of the nation’s economy. Yet the policies in place were limiting the growth of companies such as Google within the nation’s borders, something that did not seem to him to make sense.

DISCUSSION

James Socas of the Senate Banking Committee agreed that Google exemplified the company that, kept in the United States, would benefit the country. But he also listed some benefits that the company had derived from the country: employees trained at universities supported by taxpayer dollars; the U.S. regime of property protections; the money of U.S. investors, upon which it would rely when it went public; and the very capitalist system that had given the company life and helped get it through its first 6 years. In light of this, couldn’t Google go above and beyond efforts it might otherwise make to hire U.S. engineers who, presumably, would be able to compete with those the company was hiring abroad if given an opportunity on the same footing? Often heard on Capitol Hill, Mr. Socas noted, was: “ ‘Google and companies like it have benefited so much from this American system, from this American community—is it so much to ask that Google in [its] hiring look first to U.S. workers? What is it that Google owes back to the country?’ ”

Dr. Rosing answered that, in recognition of the benefit of its having been born in the United States, Google had the responsibility of trying to build a company based in the United States, which he said it was meeting. “We will hire every qualified person we can find in engineering, full stop,” he reiterated. “I put no qualification on that. And we can’t find enough of them.” Saying that the educational system and various factors in society were leading Americans to see other professions as more attractive than science and engineering, he asserted that Google by itself could do little more about this “fundamental problem” than, by going public, create interest and excitement that might inspire others to emulate the company’s founders. All Google could do otherwise was to keep hiring and to continue working on the problem of building better search technology.

Asked about attrition at Google, Dr. Rosing placed the rate at well below 1 percent for engineering employees. While speculating that this very low figure might be related to the phase of development in which the company then found

itself, he stated that Google’s interviewing process was very biased against false positives. “Frankly, we probably miss good people by being so careful,” he said, “because it’s very difficult to manage people out in the company and, especially when you have very little management, that’s a very expensive process.” Although the company had added managers, it remained “picky”; avoiding false hires had, in any event, served it well.

Why the Shortage of Qualified U.S. Graduates?

John Sargent of the Department of Commerce noted that the dot-com bubble’s collapse had ended the era in which it was difficult to find skilled employees in the information-technology area and, in fact, had left unemployment rates at record highs in almost all IT occupational specialties. If Dr. Rosing was in fact suggesting that the United States was not graduating enough students with skills adequate to meeting Google’s needs, would this be because U.S. students were inferior in quality to those trained elsewhere, or because the skills they were being taught in U.S. institutions were incompatible with industry’s needs.

According to Dr. Rosing, neither of the two alternatives applied. The United States probably remained one of the world’s top areas for computer science education, producing very good graduates. But there weren’t enough people going through the system and coming out at the master’s and Ph.D. levels to satisfy the needs of the new Information Economy that was the presumed basis for America’s competitiveness in the post-industrial world. The fundamental problem—given the excellent quality of the graduates coming out of Stanford, UC-Berkeley, and other U.S. institutions—was that not enough people were going into them. He stressed that he was speaking specifically about computer scientists and not about information technologists in general, a distinction he regarded as subtle but very important.

Dr. Myers then introduced Jack Harding, the Chairman, President, and CEO of eSilicon and a veteran of 20 years of executive management experience in the electronics industry.

CURRENT TRENDS AND IMPLICATIONS: AN INDUSTRY VIEW

Jack Harding

eSilicon Corporation

Mr. Harding introduced his firm, eSilicon, as a three-year-old venture-backed semiconductor company that produced custom chips for its customers in the same way that a general contractor might build a house for an individual. eSilicon implemented its customer’s chip specifications by integrating its deep domain expertise with the capabilities of a global, outsourced, tier-one supply chain and delivered a packaged, tested custom chip in volume with the customer’s name on

it. Among the millions of parts eSilicon had shipped were chips used in the Apple iPod and in a Kodak digital camera. Of the company’s 85 employees, about one-third were of Indian descent, one-third of Chinese descent, and one-third of “European or American” descent. As such, he said, “the notion of outsourcing and offshoring is alive and well in our business, and we deal with it in many dimensions every single day.”

Mr. Harding said he would frame the problem of outsourcing vs. offshoring from the business person’s rather than the economist’s point of view, then talk about some of the challenges and trends he and his U.S. competitors faced. He began by citing a recent statement by Autodesk CEO Carol Bartz that he called a “wonderful backdrop” to a discussion of the topic: “When you can get talent at 20 percent of the costs, it isn’t about waving the American flag. It’s about doing what’s right to have a good company.” This and a statement by Hewlett-Packard [the then current] CEO Carly Fiorina that “there is no job that is America’s God-given right anymore” typified the attitude prevailing in the commercial sector and expressed in various ways by previous speakers: “Hiring here in the United States is important, as is supporting one’s nation, but we have businesses to run and that’s going to dominate our thinking.” This thought process was being “proclaimed throughout Silicon Valley,” and echoed, although “more quietly, around the rest of the United States.”

Growing Complexity Spurs Outsourcing

The driving force behind outsourcing, as behind other phenomena characterizing the information-technology sector, was complexity. As complexity grows, a firm is forced either to stay ahead of the power curve as long as it can—which means to “sprint like crazy”—or to “step aside and let somebody else do that part of the work.” Those areas that are not part of a company’s core competency are the first to go. To illustrate, Mr. Harding cited Motorola’s decision to spin off its semiconductor business—a business the company had not lost interest in but would have had to recapitalize at a cost of $10 billion in order to stay competitive with outsourcing firms in the industry. “At the point that you’re unable to compete by virtue of cost structure or lack of overall efficiency,” Mr. Harding stressed, “you are forced to outsource.”

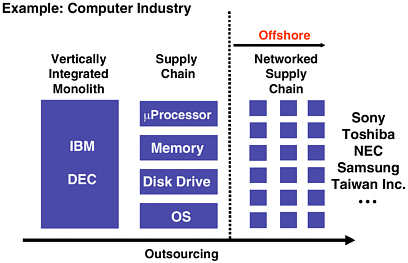

Extending this model to the computer industry, he recalled the period some 15 years before when IBM and DEC dominated the PC business as vertically integrated companies. The two rapidly disaggregated across a wide variety of companies to buy memory and processors, to the point that dozens of firms had come to participate in the PC supply chain, whose makeup was changing constantly (See Figure 28). It was as a function of complexity growth that manufacturers needed to find specialists that could fill a particular gap or solve a particular problem. This decision to outsource, he said, was the first step down a “very slippery slope” leading to offshoring. Manufacturers typically began by saying,

FIGURE 28 Outsourcing leads to offshoring.

“I can’t do it myself any longer, and so I’m going to hire somebody nearby so that I can look over them; I really don’t want to have them in a different time zone.” Upon locating a better supplier “in another county or the next state or the next country,” however, they would find themselves embarked on offshoring. Complexity and efficiency working together were, from the business person’s perspective, critical to understanding what to outsource and why; when and then where to do so; and whether doing so is worth the challenges that arise with distance.

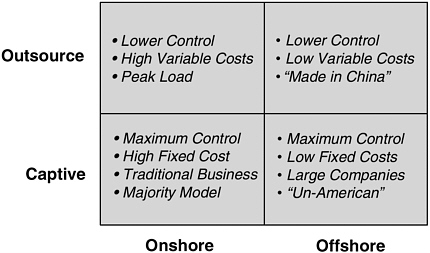

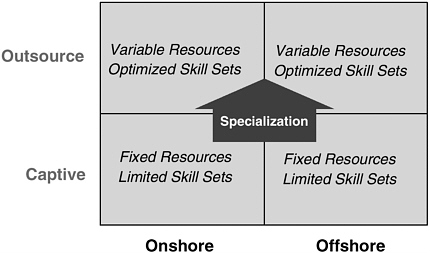

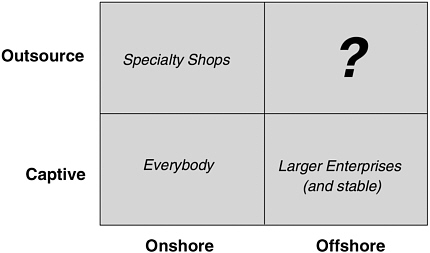

Displaying an outsourcing/offshoring matrix he said would help illustrate two points central to the ongoing policy debate, Mr. Harding called the audience’s attention to the box labeled “captive-offshore” (See Figure 29). That was the locus, he speculated, of “a lot of the political pushback of its being ‘un-American’ to take jobs to—fill in the blank—Mexico, Taiwan, China.” He cautioned those in the policy sector against relying on “a simple formula to understand the ‘un-American’ aspects of outsourcing or offshoring,” emphasizing that specific attributes and market segments merited attention. Activity that could be placed in the “outsource-offshore” box of the matrix, meanwhile, was marked by a trade-off: diminished control against very low variable costs with adequate technical expertise. Recalling the days when “made in Japan” implied questionable quality, he observed that “as you grow up, you realize that also implies things such as IP protection, bootlegged software, [and] cutting the tops off of chips.”

FIGURE 29 Out/Off matrix.

Hurdles to Accomplishing Specialized Tasks In-House

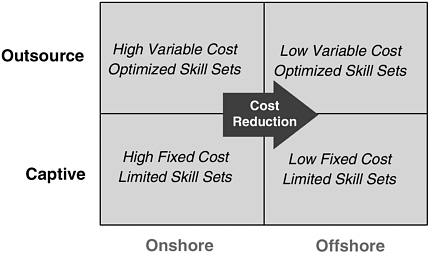

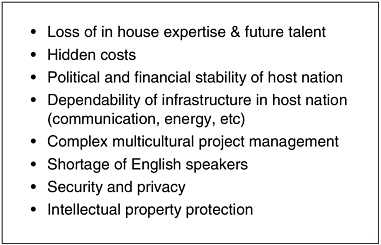

Offering an admittedly “simplistic” model that nonetheless might aid understanding of business’s outlook on the outsourcing of specialized tasks, Mr. Harding identified general hurdles—such as budget or immigration constraints, or raising the bar too high—that could limit the acquisition of specialized capability in-house (See Figure 30). Specific to companies under $1 billion in size were problems associated with having a specialist on the payroll who could not be kept busy year-round: (a) it was wasteful, and (b) workers of sufficient quality might well reject a position that would not keep them engaged full time. Such factors might incline firms to look outside for expertise needed to get a job done. “There is a fundamental notion,” he stated, “that one outsources in order to achieve a specialty skill, regardless of whether it is on- or offshore.”

Although the historical reason for going offshore, and the goal implied in the statements of Bartz and Fiorina, was to manage costs, that was not always the motive (See Figure 31). Texas Instruments, for example, had gone to India 20 years before to access a well-educated software pool, which it had managed on a captive basis since. In fact, however, the “vast majority” of the small to medium-sized companies with which Mr. Harding had come into contact were talking about going offshore to save money. Although there might be exceptions to the rule, a software company seeking venture money in Silicon Valley that did not have a plan to base a development team in India would be disqualified as it walked in the door. It would not be seen as competitive if its intention was to hire

FIGURE 30 Business drivers: outsourcing.

FIGURE 31 Business drivers: offshoring.

workers at $125,000 a year in Silicon Valley when comparable workers were available at $25,000 a year in Bangalore.

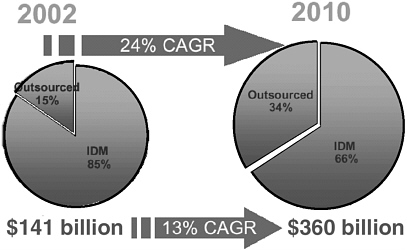

Morgan Stanley had predicted that the outsourcing market overall would grow to approximately one-third of the $360 billion semiconductor industry by the end of the decade, a big jump from around one-seventh of a $140 billion market in 2002 (See Figure 32). To suggest the role of offshoring in this change,

FIGURE 32 Outsourcing trend: semiconductor revenue by source.

SOURCE: Morgan Stanley Research.

Mr. Harding showed a graph tracing the growth of India’s software industry from almost nothing to $10 billion in around the same number of years and noted that it had shown no signs of slowing down. The strength of the offshoring trend, he said, made imperative that the United States find a way to become comfortable with it, both from a business and from a public-policy perspective.

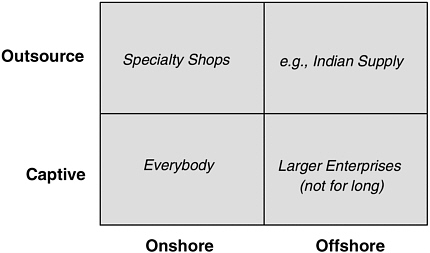

Moving Software Development Offshore

Mr. Harding then showed a matrix whose purpose was to organize discussion of the specific topic of moving software development offshore (See Figure 33). Starting with the quadrant defined as “offshore-captive,” he pointed out that placing only large enterprises there most likely represented an inaccuracy. While historically it had been companies like TI, Motorola, and Microsoft that hired software developers in India or elsewhere abroad, having a foreign presence had become incumbent even on startups seeking venture capital, as mentioned above. He said that every company he knew of, without exception, was in the process of moving software development to some degree to the Indian marketplace, and that it was inconceivable that any firm would rule such a move out. Although eSilicon itself, a hardware developer that provided its customers with hardware design from time to time, did not yet have an offshore facility up and running; it had made the decision only 2 weeks before to start one. “I consider myself a laggard in that respect,” he said. “I’m looking around and saying, ‘I’m the last guy on the block to do this.’ ”

FIGURE 33 Offshoring software.

Offshore-outsourced software development worked first and foremost because of low costs: While costs were increasing compared to previous years, it was still cheaper per person to build software abroad, even taking productivity issues into account. There was a large supply of graduates outside the United States, and the number of graduates at home had diminished to the point that it was difficult to hire good people. Mr. Harding agreed with Dr. Rosing that neither U.S. education nor the students it produced were at fault, but that with the number of graduates down employers were forced by competition for their services into paying them too much. “You’re paying master’s-level grads out of a fine school around $100,000 to come in and be an apprentice, essentially, for the first 3 years,” he commented. “That’s not a sustainable model.”

The other key factor in favor of offshore-outsourced software development was that the tools involved were, effectively, a commodity. They were robust, had a broad user base and well-developed support infrastructure, and benefited from strong standards. This was significant because, with each advancement of a software product, 18 percent of functionality was lost owing to inability to manage the bugs associated with it. From his days as head of a large software company, Mr. Harding recalled that every time the firm released a new product, it enabled new bugs even as it fixed bugs that were on its customers’ top-ten lists. “It’s a never-ending process,” he lamented. Hence the advantage of having the tools that, while not perfect, was ubiquitous and could be operated effectively by millions of people.

Mr. Harding then paused to offer a comparison between offshore outsourcing of software and offshore outsourcing of hardware that left the former looking in

FIGURE 34 Offshoring hardware.

better shape. Drawing a contrast to both the matrix quadrant for software “offshore-outsource” and that for hardware “offshore-captive”—the latter housing any of “25 first-rate electronics firms that do this very successfully”—he argued that no market of any major account yet existed for offshore-outsourced chip hardware (See Figure 34). The reason was that, unlike enterprise software tools, those for chip hardware were not ubiquitous and needed more technical support to make them work. They had a limited user base of tens of thousands of people maximum against millions for enterprise software. In addition, the farther production strayed from Silicon Valley, the hub of design-automation software, the more difficult it was to get the support that was needed to repair a bug, get a patch, or solve whatever other class of problem arose.

Policy Issues: Job Redistribution, Education

Moving to policy issues, Mr. Harding first mentioned loss or redistribution of jobs, then education: Would people come to the United States, get an education, and leave? Or would they not come at all, because the market had shifted to other zones? A third issue was U.S. access to foreign markets—and not only to customers’ dollars that might be earned, but also to the R&D and intelligence residing there. All three issues involved risk from a policy perspective, he warned.

In conclusion, Mr. Harding called the outsourcing and offshoring trends “irreversible” and said they needed to be dealt with. “We’re going to have to be articulate and thoughtful about all of these points,” he stated, “and also respectful of both sides of the argument.” He boiled down the debate over offshore out-

sourcing to the single question that, he said, was likely to be the most relevant to those in attendance—and also most likely, somewhat unfortunately, to occupy politicians’ field of vision: Are we trading jobs for earnings per share? It was the task of the business community, he said, to teach its constituencies that contrasting models can coexist.

DISCUSSION

Asked when he expected Indian firms to begin taking his own market share, Mr. Harding replied that his particular firm was unlikely to be at risk because it aggregated many elements of a complex supply chain, such as wafer production from Taiwan and packaging from Korea. As a very small percentage of its business was actual design—of either software or hardware—it accessed the market directly. “There is no one company in India that would have the advantage over us,” he said. “They still have to buy from the same suppliers from whom we buy.”

The IT Sector’s Judgment Questioned

David Longstreet of Software Metrics said that what he had observed through working with companies to put measurements in place prior to outsourcing agreements ran contrary to what Mr. Harding had been suggesting. “When we have measurements in place before and after,” he claimed, “what we see is lower quality and lower productivity like for like.” Recalling the IT sector’s recent missteps—“we were wrong about Y2K and we all rushed to that, we were wrong about dot-coms and we all rushed to that”—he recommended that the industry “learn to tread lightly” and get better measurements in place before rushing to India to outsource software. Warning that the industry was again “rushing to something that is actually drawing a lot of companies to lower earnings,” he asked: “Why should an investor believe IT now, when we’ve been wrong the last two major times?”

When he had been in the software sector, Mr. Harding countered, he had had 300 or 400 employees in India producing software of the same quality as that coming out of Silicon Valley. Hardware was a different story, however, prominent among the reasons being “the availability and application of complex design tools that break easily.”

Kenneth Walker of SonicWALL stated his disagreement with Mr. Harding’s point on hardware outsourcing, which, he said, was mainly based on the latter’s limiting the definition of hardware to chips. Design and production of such hardware systems as TiVo devices, TV sets, and monitors were being outsourced to Taiwan and other countries in large quantity, he noted.

Acknowledging Mr. Walker’s comment as fair, Mr. Harding nonetheless argued that the assembly of the items Mr. Walker had mentioned differed in respect to the percentage of the cost of goods sold from the development of the

semiconductor components enabling those particular items. System-final assembly certainly was dominant in Asia, which, he added, was the right place to do it.

Dr. Myers then introduced Ronil Hira, a member of the Public Policy faculty at Rochester Institute of Technology (RIT) who specialized in workforce issues and innovation policy.

IMPLICATIONS OF OFFSHORING AND NATIONAL POLICY

Ronil Hira

Rochester Institute of Technology

Dr. Hira specified that he was addressing the conference in two capacities, one as a representative of RIT, the other as chair of the Career and Workforce Policy Committee of the IEEE-USA. The committee, which represents the 235,000 U.S. members of the IEEE, itself a transnational organization, was started in 1972 in response to poor labor markets for engineers early in that decade.

Dr. Hira began by offering a set of definitions:

-

Outsourcing: a classic make-or-buy decision between producing in-house or purchasing from a supplier. Example: Procter & Gamble contracting with Hewlett-Packard for information-technology services.

-

Offshore outsourcing: using a supplier operating abroad. Example: HP’s recently reported attempts to “move as much [work for clients] offshore as they can.”

-

Offshore sourcing, or offshoring: a multinational corporation that operates offshore. Example: Daimler Chrysler’s R&D center in Bangalore.

-

Onsite offshore outsourcing: Bringing foreign workers into the U.S. to work on a project onsite, often on an H-1B or L-1 visa. Example: Tata Consultancy Services, Infosys, Cognizant, Accenture, Wipro, or Satyam providing foreign nationals to work in U.S. domestic operations.

Prominent on the list of factors encouraging U.S. companies’ use of overseas technology workers were lower labor cost; access to exceptional talent; access to local markets; tax holidays and other industrial-policy measures by countries that are targeting these jobs and industries; and the option to operate around the clock. According to Dr. Hira, however, the strongest motivation had been that companies had become aware of this possibility and believed that taking advantage of it would help their performance. “They’re acting rationally,” he said, noting that firms follow whatever course permitted by existing rules “they think is in the best interest of the shareholders and management.” For this reason, it was his practice to refrain during policy discussions from making appeals to companies’ patriotism or moral character; doing so, he said, “makes no sense.”

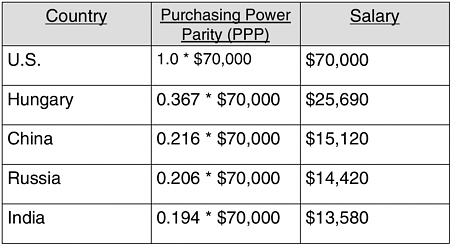

Do Foreign Engineers Truly Work for Less?

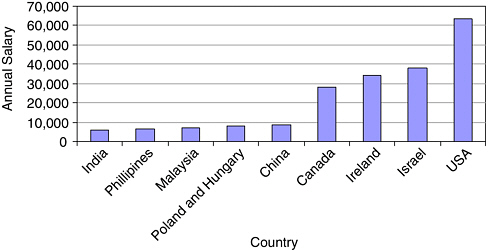

Taking up the first entry on the list, labor cost, Dr. Hira displayed a chart comparing salaries for engineers in the United States and several other countries (See Figure 35). Using data expressed in purchasing power parity strongly suggested that, given the variation in the cost of living among nations, it was a misconception that workers outside the United States were willing to work for less. In fact, these workers could afford to be paid significantly less than workers in the United States because, even at lower wages, they would be just as well off. He nonetheless cautioned against the capacity of the purchasing power parity measure to reflect economic reality, noting that in India, he was able to buy a tomato for the equivalent of two U.S. cents, but housing is relatively more expensive in India. He disagreed with those who expected prices to rise very rapidly in India, positing that “there’s kind of a governor on that effect,” as well as with those who saw wages going up quickly as demand for labor increased. “There’s a lot of labor [available] there,” he observed.

That no one could say how much software work actually had moved offshore to that point was called a “major problem” by Dr. Hira. There was no one in the federal government collecting data, although a pilot study of the question had begun in the Commerce Department. That effort, budgeted at only $300,000, would of necessity be a modest one and perhaps of most interest to those firms already outsourcing offshore; he expressed the opinion that, if it was to be addressed at all, the issue should be addressed more seriously. But getting an accurate picture was difficult, as two concerns had made companies quite reluctant to reveal their plans in this regard: (1) that they would take a public-relations

FIGURE 35 Overseas software engineers can afford to be paid less.

hit, and (2) that they would face workforce backlash as their employees found themselves effectively training their own replacements as part of what was euphemistically known as “knowledge acquisition” or “knowledge transfer.” The easiest way to find out what was happening was to read in online editions of Indian newspapers the numerous announcements of major U.S. corporations expanding their activities there and the financial statements of the major IT offshore outsourcers like Cognizant, Infosys, and Wipro.

Higher-Level Jobs Have Joined the Exodus

A common misconception, although one not shared by the day’s previous speakers, was that only low-level jobs were moving offshore. Evidence to the contrary had been provided by the Detroit Free Press, which had reported not long before that General Motors was moving some of its R&D abroad. Daimler-Chrysler had R&D operations in Bangalore, and Texas Instruments had been there for some time. But the evidence suggesting that higher level jobs were involved was largely anecdotal, we don’t know the true scale and scope, so honest discussion of the situation would have to await more scientific data. Meanwhile, estimates of the number of jobs expected to go offshore had come from firms like Forrester Research that were self-interested in that, as suppliers of advice and other services to firms considering the offshoring option, they stood to benefit from promoting the idea. Furthermore, in Forrester’s case the report had been released over a year before, but its numbers were still frequently cited despite the fact that business strategies had changed significantly in the interim.

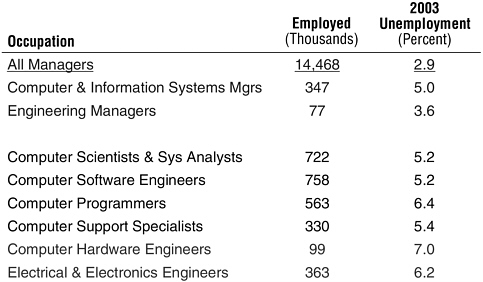

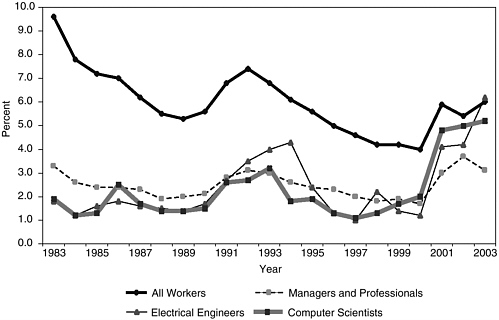

Dr. Hira displayed a breakdown of employment totals and jobless rates in the U.S. domestic IT labor market, which he said was experiencing “record unemployment” (See Figure 36). He cited a frequent reaction to this table: “That’s not a big deal, it’s pretty close to the general unemployment rate.” But his next graphic, depicting unemployment rates in the technology sector over the previous two decades, provided a perspective (See Figure 37). While the general civilian unemployment rate had trended downward between 1983 and 2003, the rate for computer scientists, after staying in the 1-3 percent range from 1983 to 2000, had climbed to over 5 percent by 2003. The rate for electrical engineers had actually fared even worse over the previous year, surpassing the general unemployment rate in 2003 for the first time in the several decades during which such data had been collected. Nevertheless, over the preceding year the SOX index, which measures the performance of semiconductor-industry stocks, had doubled. “So maybe there’s some hope,” he speculated. “We’ll see when that hiring starts to pick up.”

Offshoring’s Contrasting Long- and Short-Run Impacts

A change in the mix of U.S. domestic occupations, with attendant job dislocation, was one consequence of the departure of technology jobs overseas that

most observers were predicting. While some hoped offshoring would make the U.S. IT job market stronger in the long run, the opposite impact was expected for the short run. Just that week, in fact, Siemens had announced the relocation of almost all the software developers it had been employing in the United States and Western Europe—a total of 15,000—to Eastern Europe, India, and China. “At least they’ve announced it publicly,” Dr. Hira declared. “A lot of people are probably planning it and not saying it.” Such moves were apt to prolong unemployment duration in an IT labor market that was weak already, as well as exercise downward pressure on wages. BusinessWeek had recently reported that an employer located in Boston placed an ad to hire a senior software engineer at $40,000 just as a lark and received about 90 responses from highly qualified senior software engineers, who were normally paid twice that. Such downward wage pressure had been characterized as the silver lining of the movement offshore by an IT industry representative, Harris Miller, who argued that forcing down wages at home would mean that the United States could keep more jobs. A business magazine columnist, perhaps similarly, had voiced surprise that anger over offshoring was real. The reason for the anger, Dr. Hira suggested, was that “unlike what some are saying—‘your job is not moving to Bangalore’—for a lot of software people in fact it is, at least right now.”

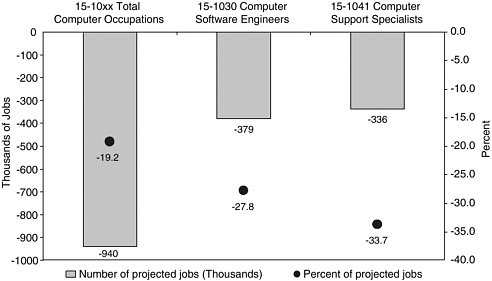

As to the decade ahead, he displayed a chart showing that the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) had just revised downward by nearly 1 million jobs its forecast for overall job creation in computer-related occupations (See Figure 38).

FIGURE 38 Occupation mix—revised BLS job projections: Decrease in number of jobs forecasted, 2002–2012 projections vs. 2000-2010.

SOURCE: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

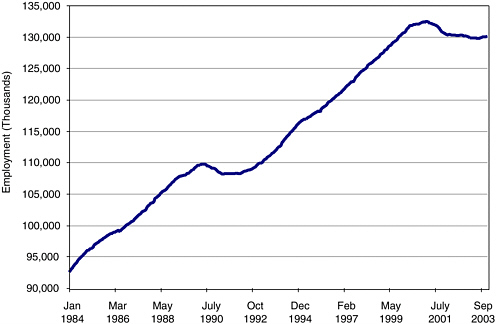

In updating its projections to run through 2012, the BLS had predicted that, instead of growing from 3 million to 5 million, this job category would grow to only 4 million. While expressing skepticism as to how accurately the occupation mix could be predicted 10 years out, Dr. Hira explained that the chart was a means of countering assertions that the nation would be creating large numbers of “great jobs” in IT and so there was nothing for the sector’s employees to worry about. “I hope that the people who are using that as an argument start to update at least some of that data,” he remarked. A second chart, this one tracking job creation from 1984 to 2003, showed that the United States’ job-creation engine had stalled beginning around 2000 (See Figure 39); even if the general trend resumed in the long run, in the short run employees were being displaced. “They’re not going to the IT occupations, where jobs are not going to be created,” Dr. Hira stated. “Are they going to go somewhere else? To what professions?”

He raised a number of questions regarding the longer-term impacts offshoring might have on U.S. innovation:

-

Was it important to maintain a strong software and engineering workforce in the United States?

FIGURE 39 Job dislocation during low job creation: Total nonfarm payroll employment (seasonally adjusted).

SOURCE: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

-

What would the country’s new occupation mix be if software were lost?

-

Would losing software have a chilling effect on people’s pursuing IT occupations and disciplines?

-

Where would the future’s technology leaders be developed?

In apparent contradiction to previous speakers’ contention that not enough Americans wanted to study computer or software engineering, U.S. enrollments in computer engineering had jumped to 78,000 in 2002 from 48,000 in 1998. But if a lot of people were again looking upon computer engineering as a good profession, would that continue into 2004 and 2005?

Analyzing the Optimistic Analysts’ Optimism

Dr. Hira then called attention to a pair of studies that had been promoted by offshoring advocates and that he qualified as “optimistic.” McKinsey Global Institute had claimed in a study called “Offshoring: Is It a Win-Win Game?” that the United States netted out 12-14 cents of benefit for each dollar spent offshore. Pointing to some of the study’s limitations, he noted that no one had access to McKinsey’s proprietary data and that the models used in the study were not explicit, so that there was no possibility of testing its assumptions using basic sensitivity analysis. Furthermore, its “very rosy” reemployment scenario—“an important part of its argument for how [offshoring] is a net benefit to the U.S.”—did not hold up in the current labor market, nor did it account in the longer run for impacts on innovation and security that might be felt as change in the country’s occupation mix exercised a chilling effect on both the software and engineering fields. Finally, McKinsey failed to disclose in its study several sources of potential conflict of interest: that it sells offshore consulting services; that India’s software services trade association, NASSCOM, had been its client for some years; and that the former director of McKinsey was acting as the head of the U.S.-India Business Council. “I hope we’re not resting our future on that particular study as being definitive,” he remarked.

The second study, by Catherine Mann of the Institute for International Economics, based its optimism in part on the unrevised BLS occupation projection data (discussed above), as the updated figures had not yet become available when it came out. Dr. Hira called for reinterpreting this study in light of the more recent data; he also stated his disagreement with its contention that lower IT services costs provided the only explanation for either rising demand for IT products or the high demand for IT labor witnessed in the 1990s. He cited as contributing factors the technological paradigm shifts represented by the growth of the Internet, ERP, and Object-Oriented Programming; the move from mainframe to client-server architecture; and the upswing in activity surrounding the Y2K phenomenon.

Black-and-White Thinking Hinders Policy Debate

Turning to what he considered to be “policy-dialogue impediments,” Dr. Hira argued that offshoring was affecting workers much more than it was companies, and that the latter felt no urgency to fix a problem they were not experiencing. Discussion of the issue, he said, should not be couched in the “good vs. bad” terms that had too readily defined it as a battle of “free trade vs. protectionism.” Instead, the focus should be placed on assessing both the “good” and the “bad” that might result, and on how the potentially negative effects of offshoring might be mitigated.

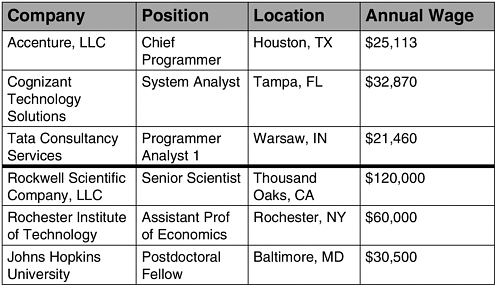

Dr. Hira next displayed a table constructed using U.S. Department of Labor data from the labor condition applications (LCAs) that companies had to file in order to hire a foreign worker on an H-1B visa: the company’s name, the title of the position it was seeking to fill, the place where the work would be done, and the prevailing wage for that position at that location (See Figure 40). The three companies listed above the bar were in fact engaged in onsite offshore outsourcing and offered annual salaries in the range of $21,000 to $33,000, which are significantly lower than the market rates for those occupations. Dr. Hira included Rockwell Scientific in the table because it had been put forward by industry advocates as a company that badly needed H-1B visas, which would enable it to hire exceptionally talented employees whom it was in fact paying $120,000 a

FIGURE 40 Current H-1B and L-1 Visa laws enable and accelerate offshore outsourcing.

SOURCE: U.S. Department of Labor LCA database, <www.flcdatacenter.com>.

year to work at its facility in Thousand Oaks, Calif. In the interests of comparison, he also posted the positions of assistant professor of economics at his own institution, which pays $60,000, and of post-doctoral fellow in the biological sciences at Johns Hopkins, whose $30,000 salary level “might explain why a lot of people in America aren’t too happy doing post-docs in life science.” But it was the low level of the salaries being paid to workers from abroad that so many U.S. IT workers found problematic. “If work needs to be done in the U.S., it should be done by domestic workers unless you can’t find a domestic worker,” he stated, although he conceded that “maybe you can’t find a domestic worker for $21,000.” Also, the firms above the bar, all offshore outsourcing firms, are importing orders of magnitude more foreign workers on H-1Bs than firms like Rockwell Scientific.

Dr. Myers then introduced William Bonvillian, the Legislative Director and Chief Counsel to Senator Joseph Lieberman of Connecticut.

OFFSHORING POLICY OPTIONS

William B. Bonvillian

Office of Senator Joseph Lieberman

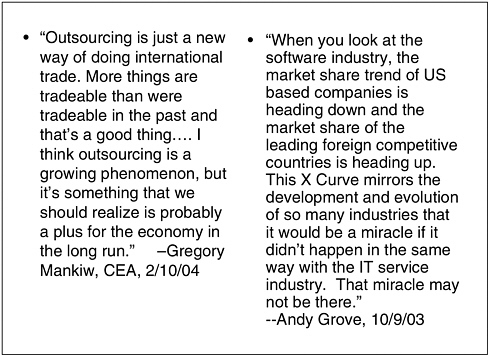

Mr. Bonvillian36 began by posting what he called “two fighting quotes from the current times,” one from Gregory Mankiw, the chairman of the President’s Council of Economic Advisers (CEA), and the other from Intel Corporation Chairman Andy Grove (See Figure 41).

Mankiw, after loosing a “storm in Washington” with his pronouncement, had all but disowned it, but the points he had made initially were nonetheless classic defenses of outsourcing tendencies:

-

that outsourcing was just a new way of doing international trade;

-

that many things were more tradable than they had been in the past, which was good; and

-

that outsourcing was on the rise and should be viewed as a plus for the economy in the long run.

FIGURE 41 Mankiw vs. Grove.

Grove’s statement, which had been circulated widely in the nation’s capital around the same time, reflected the other side of the coin. The two together provided a backdrop for the discussion.

Forrester had projected that 3.3 million U.S. IT service jobs and $136 billion in wages would go offshore over the following 15 years, while McKinsey had predicted a 30-40 percent annual acceleration over 5 years in the number of such jobs lost to outsourcing. Mr. Bonvillian said he had seen an even more extreme prediction: that a total of 14 million IT service jobs would disappear from the United States in that manner within a decade. He was skeptical of these projections because the relevant government agencies were not collecting the foundation job data. Nonetheless, while very significant declines in IT employment might be led by IT manufacturing, IT services would be right behind. Although the lack of data made it impossible to track the activity of the many companies engaging in overseas outsourcing, it was clear that the phenomenon was not restricted to any one sector. From low-end services—like call centers, help desks, data entry, accounting, telemarketing, and processing work on insurance claims, credit cards, and home loans—it was moving increasingly toward such higher-tech, higher-end services as software, chip design, consulting, engineering,

architecture, statistical analysis, radiology, and health care centers. And those were only some of the leaders.

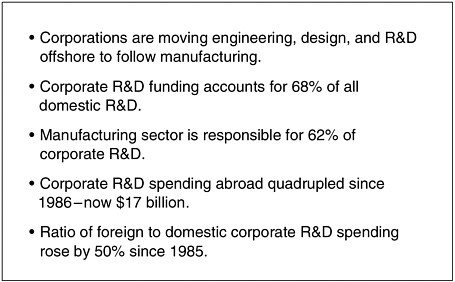

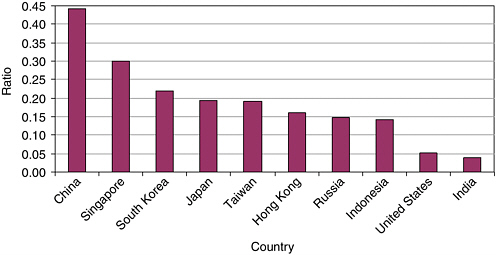

R&D Following Manufacturing Overseas

Another, parallel phenomenon, mentioned earlier by Dr. Hira, needed to be kept in mind: the growing trend of moving R&D offshore so that it would be closer to manufacturing (See Figure 42). The country had already lost 2.6 million manufacturing jobs, many of them in the tech sector during the 2001 recession and post-recession, and R&D had started to follow. A significant part of the R&D going abroad had been very high-end, very capable; in semiconductors, to pick one example, it was very important to have R&D and design close to the manufacturing stage. R&D spending abroad by U.S. corporations had quadrupled since 1968 to about $17 billion, and, since 1985, the ratio of foreign to domestic corporate R&D spending by U.S. firms had risen 50 percent. “These are big numbers,” Mr. Bonvillian observed, which U.S. policymakers had to “begin to understand.”

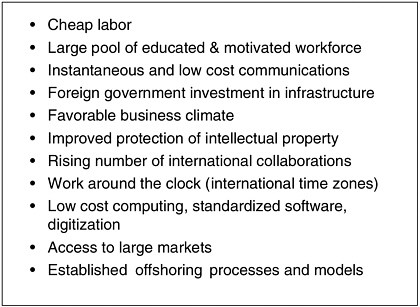

He then posted a pair of lists—of factors behind the exportation of U.S. jobs in services and R&D (See Figure 43), and of risks involved in transferring business functions abroad (See Figure 44)—without commenting on them other than to say that moving offshore is “not necessarily a simple equation [but] a complicated business transaction.” Another graphic, this one illustrating the differences in salary levels for computer programmers from country to country (See Figure 45),

FIGURE 42 R&D trends.

FIGURE 43 WHY is the U.S. losing service and R&D jobs to overseas?

FIGURE 44 Risks associated with moving offshore.

was offered in explanation of the offshoring trend. Both it and a chart representing differences in the ratio of engineering degrees to total bachelor of science degrees in the United States and China, among other countries (See Figure 46), depicted what he judged “startling historical developments.”

FIGURE 45 Annual salaries for a programmer in various countries.

SOURCE: Computerworld, April 28, 2003.

FIGURE 46 Ratio of engineering to total B.S. degrees awarded in various countries.

SOURCE: National Science Foundation, Science and Engineering Indicators.

While offshoring’s impact on the U.S. economy was hard to ascertain using the limited data available, a debate had begun between optimists adhering to classical economics and some who had been voicing a more general but growing concern about the country’s economic future. The former argued that offshoring would yield such benefits as lower product and service costs, new markets abroad fueled by improved local living standards, and more latitude for U.S. corpora-

tions to focus on core competencies at home. The other side, goaded by what Mr. Bonvillian dubbed the “Uh-oh Factor,” and seeing growing world competition over innovation capability, cited downward pressure on wages for high-skill jobs, as well as diminishing talent, tax, and investment bases at home. Such concern, having become “in many ways a storm,” was starting to buffet Capitol Hill.

Will Offshoring Erode Technological Comparative Advantage?

He then accorded special consideration to the argument that offshoring’s movement up the value chain is accompanied by potential loss of technological competitive advantage. This could be seen as an emerging bone of contention between classical economics and the growth economics school. A representative of the latter, Clayton Christiansen of Harvard, had written that low-end entry and capability fuel the capacity to move into higher-end markets.37 This familiar pattern of economic expansion, typified by the progression from the Corolla to the Lexus over time, had been replicated in any number of industries. “We have to understand that low-end competition now is not necessarily going to end at those low-end levels,” Mr. Bonvillian warned.

Similarly, Michael Porter had contended that if high-productivity jobs are lost abroad, then long-term economic prosperity is compromised.38 Some growth economists, echoing real estate agents, had placed the emphasis on “location, location, location.” Porter himself had done a great deal of work on “clustering,” the notion that it is possible to create a competitive force that is regionally based and collaborative across different sectors and institutions. The cluster spurs upgrading because it stimulates diversity in R&D approaches and provides a network mechanism for introducing new strategies and skills. Location is a key element: Since there is a tremendous skill set involved in the different work functions at an advanced-technology factory, losing a significant part of that manufacturing will affect the cluster’s ability to thrive in its region. And when such loss is taking place on the service and R&D sides as well, another set of issues arises on top of that. According to John Zysman, who has maintained that manufacturing matters even in the Information Age, the advanced mechanisms for production and the accompanying jobs are a strategic asset, and their location makes the difference as to whether or not a country is “an attractive place … to create strategic [economic] advantage.”39

“A Different Kind of Competitiveness Story”

What all this added up to, Mr. Bonvillian said, was “a different kind of competitiveness story.” Although the debate outlined above might seem familiar from the 1980s, a new set of competitors had emerged and the competitive situation had grown far more complicated:

-

In its competition against Japan during the 1970s and 1980s, the United States was facing a high-value, high-wage advanced-technology country very similar to itself, whereas competing against China meant competing against a low-wage, low-value increasingly advanced-technology country.

-

The United States, one could argue, had been able to use its entrepreneurial advantage to offset Japan’s advantage in industrial policy. China, in contrast, was not only a very entrepreneurial country, it was making intense use of industrial policy in pursuing such aims as capturing the semiconductor sector.

-

The rule of law, which was a common assumption in competition with Japan, is still an emerging idea in the competition with China. By a similar token, Japan protected intellectual property, while an “intellectual property theft model” unfortunately structured much of the Chinese competitive environment; according to one source, the FBI estimated at around $250 billion per year the intellectual property theft in China of U.S.-bred products and ideas

-

Japan was a national-security ally, China a potential peer-competitor.

One constant had been that both Japan and China had undervalued their currency and bought U.S. debt, in consequence of which the United States was not in a position to push its trade arguments vigorously. China would maintain as long as it could the low value of its currency while continuing to buy U.S. debt at massive levels, he predicted, so it can retain leverage over U.S. economic policy.

With data scarce and concern “enormous,” a multitude of bills had been introduced in Congress, which, according to Mr. Bonvillian, sometimes reflected a move toward a protectionist outlook. Under a bill offered by Sens. Edward Kennedy and Tom Daschle, companies that sent jobs abroad would have to report how many, where, and why, giving 90 days’ notice to employees, state social-service agencies, and the U.S. Labor Department. Senator John Kerry had introduced legislation requiring call-center workers to identify the country they were phoning from. Other bills would require government contractors to have 50 percent of their employees in the United States, prohibit work under federal contracts from being performed outside the country, or bar companies that outsourced jobs from contracting with the federal government. Legislation that had failed three years before, but was being revived would extend Trade Adjustment Assistance (TAA), up to then available only in the case of manufacturing jobs that had been offshored, to service-sector jobs as well—a proposition bringing with it a complex

definitional issue.40 And the Genuine U.S. flag Act, one of his personal favorites, would prohibit the purchase of American flags made outside the country.

Discovering That Services Are Not Invulnerable

U.S. policy makers’ previous exposure to manufacturing issues had helped build their sophistication in responding to competitiveness problems in that sector. But, not having envisioned significant competitive threats to the country’s service sector, which had been regarded as “golden,” and invulnerable, they found themselves confronting what Mr. Bonvillian called a “complicated dilemma.” After taking the initial step of collecting data, lawmakers would be obliged to “think about some safety nets” in light of the fact that the voices of their constituents had grown “loud” on the subject. Among the areas of potential response in the near term were:

-

Retraining. “A much more effective, rapid, and agile-workforce training set of programs,” with interactive IT playing a role, would be required.

-

Compensation. Options included Trade Adjustment Assistance (TAA) for services; job-loss insurance, which had been featured in a pilot program in previous TAA legislation; and asset building compensation features. Novel thinking about incomes and assets was in order, Mr. Bonvillian said, because “in the kind of economy we’ve got now, holding assets is probably much more enduring than simply relying on straight incomes. Our upper-middle class has that capability, but it doesn’t go very far down the chain. And how do we start to turn that perspective around in governmental policy?”

-

Trade. The large U.S. apparatus for negotiating trade deals had limited capability for looking at ongoing and shifting barriers to market entry that U.S. companies faced, and for prompt action against unfair competitive practices. Much hard work was ahead, starting with attempting to cope with “a tremendous amount of just straight industrial policy … that is likely GATT violative,” such as the VAT rebate China was providing on domestically manufactured semiconductors.

-

Financing. Means needed to be found for bringing spending from the venture-capital system off the sidelines and back into the economy.

In the longer term, if economic growth theory was right, the country would have no choice but to innovate its way out of the situation. As a consequence, far

more serious thought had to be given to the national innovation system, raising such questions as:

-

How might the United States increase the speed with which it brings on the “next big things”?

-

How should it cope with talent issues surrounding math and science education?

-

How could the number of “prospectors” in the nation’s innovation system be increased, and how could they be given the skill sets not just to make discoveries, but to grow companies?

-

Could the country invest in R&D in such a way as to spur the development of targeted new technologies, especially in the physical sciences? If the U.S. is going to have to compete in high-end services, could it build up its negligible services R&D and accelerate services innovation?

-

What could be done to break down barriers to entry for truly high-speed broadband which could spawn a new generation of IT applications, and how should growth of this broadband infrastructure be augmented?

DISCUSSION

Charles Wessner of the STEP Board pointed to a disjunction between the ability of both the economy and the policy process to adjust and the time required to take any of the long-term steps listed by Mr. Bonvillian. The lag effects of 7 years of substantial cutbacks in the federal R&D budget, which STEP had documented, were expected to hit.41 A suggestion had been made that even were the United States to pursue a trade case against China, around 18 months would be required to file it—the “equivalent of letting people rob the bank for 18 months before you pick them up”—and China would have completed planned investments on its 300 mm wafer-fabricating plants by then. “We know there’s a fire, and we’re not able to bring hoses to bear,” he contended, characterizing U.S. policy as “bankrupt.” At the same time, although Europe appeared so much less agile than the United States, European nations boasted very high standards of living and employment rates with high-wage, high-welfare jobs. Although Europe did have a structural unemployment problem, with the rate somewhat higher than that in the United States, European countries were in a position to pay their residents not to work. “Do they have any secrets?” he asked. “How do they do it?”

Mr. Bonvillian responded that Europe’s safety-net structure was much more profound than that of the United States, whose government was so limited by long-term fiscal obligations that it did not have the resources to construct a new

set of safety nets. He said, however: “If you have to choose between some key investments in safety nets vs. some key investments in your innovation system, I’d put the money on the innovation system.” He acknowledged the existence of serious short-term concerns and conceded that the economic recovery then taking place was of a very different kind from any he’d seen before: Companies were recovering while jobs were not, a phenomenon that might turn out more enduring than many suspected. But if growth economics proved right, and the bulk of growth came out of technological and technologically related innovation, then the only course of action was to get the nation’s “innovation house” in order.

Can the United States Innovate Its Way Out?

Egils Milbergs of the Center for Accelerating Innovation observed that the issue of employment was creating political pressure for President Bush that was compounded by the statistical difficulty of making job forecasts. There had been a loss of jobs owing to offshoring, and the BLS’s job-market projections, in particular those for IT jobs, had kept coming down. Automation, much of it driven by software, was causing productivity to increase and, at the same time, shrinking the need for workers. According to a recent study by the New York Federal Reserve Board, 75 percent of layoffs were now permanent—up from around 50 percent in previous downturns—so jobs would not be restored with a cyclical upturn. In short, the job outlook was “pretty downbeat.” Referring to the prospect mentioned by Mr. Bonvillian of “innovating out of the problem,” Mr. Milbergs suggested that Wal-Mart employed more people than had the entire Internet economy, even if the latter could be credited with generating 1 million jobs. “I’m wondering how we see ourselves out of this,” he stated, asking whether the situation on the employment front could be expected to turn around in the following 18-24 months.

In response, Dr. Hira noted that recent employment data demonstrated not job creation but job destruction, and he speculated that, if the reverse were true, offshoring might be less controversial. Not unlike economists, he was unable to pinpoint the causes of the trend; therefore, he was hesitant to try projecting even 18 months out. Rather, he saw the question thus: “What do you do now, and how much damage does this current situation create for future innovation?” Evidence of the climate’s chilling effect on engineers and software developers, he said, was that they tended to converse among themselves about offshoring instead of about attending technical conferences and advancing technology, and they did not feel their concerns had met with a straightforward response. “They’ve been told over and over again, ‘This is actually good for you, because it frees you up.’ Well, it frees you up to do what?”

Dr. Varian had two points to contribute to this discussion:

-

“Be wary of focusing on just one industry.” There were different trends in different sectors, he said, citing a recent report in The Economist that the

-

majority of biotech research was moving to the United States because world-high prices for pharmaceuticals made it attractive to sell here and because of the importance of locating production close to the market.

-

“Look at the medium term.” Focusing on 7 years out, rather than on 2 years out or on 10-15 years out, would bring into view the huge labor-market upturn that would be hitting with the baby-boomers’ retirement. That would create job loss—“quote-unquote”—for voluntary rather than involuntary reasons, and the country would need skilled labor. While he recognized that those currently unemployed might find little solace in this prospect, he said that the kind of policy responses previously mentioned—encouraging education in America of engineers, loosening some restrictions on technological development—would be very important in 7, 8, or 9 years.

Concluding the panel, Dr. Myers said that a speech by Alan Greenspan then posted on the Federal Reserve Web site would probably be worth keeping in mind while seeking solutions. He paraphrased the Fed chairman as saying that the nation had learned over the previous 50 years that a flexible and adaptive economy was the most robust with respect to unexpected events leading to downturn. Dr. Myers interpreted this to mean that the solutions base had to be adaptive rather than fixed in such a way that the economy could not adjust to the changes that were bound to occur. He then thanked the speakers for their presentations on what he deemed a very provocative subject.