Executive Summary

A traumatic braininjury (TBI)—abrain injury caused by a sudden jolt, blow, or penetrating head trauma that disrupts the function of the brain—can happen to anyone. A high school quarterback collides with a running back and lies unconscious on the playing field. A young mother suffers a fractured skull and concussion when her minivan is blindsided by a drunk driver. A bicyclist loses control of his bicycle when it hits a rut in the pavement, flips over the handlebars, and lands head first in the street, losing consciousness. A 5-year-old child loses consciousness after darting into traffic and being struck by a car. A soldier survives a roadside blast in Iraq, but the explosion causes his brain to move violently inside the skull.

The effects of a TBI vary from person to person, depending on the force dynamics of injury and the patient’s anatomy and physiology. When a TBI occurs, the brain may be injured in a specific location or the injury may be diffuse and located in many different parts of the brain. The potential effects include a broad range of physical, cognitive, and behavioral impairments that may be temporary or permanent. People with TBI-related disabilities and their family members and caregivers need comprehensive, coordinated, person-centered systems of care that attend to their changing needs long after their acute injury has been treated medically. At least 5.3 million Americans are estimated to have a TBI-related disability.

The Health Resources and Services Administration’s (HRSA) TBI Program, initially authorized by the Traumatic Brain Injury Act of 1996 (P.L. 104-106) and reauthorized by the Children’s Health Act of 2000

(P.L. 106-310), is a modest federal program with broad ambitions: a $9 million grants program aimed at motivating states to create systems improvement on behalf of persons with TBI with disabilities and their families. As explained further below, the HRSA TBI Program encompasses two grant programs: (1) the TBI State Grants Program; and (2) the Protection and Advocacy for TBI (PATBI) Grants Program. The program was designed with the underlying premise that distributing small grants to states that meet certain requirements will be sufficient to initiate the creation of sustainable infrastructure and increased capacity for comprehensive, coordinated, and integrated services systems to meet the post-acute needs of persons with TBI and their families.

In 2004, the federal Office of Management and Budget (OMB) questioned the effectiveness of the HRSA TBI Program, noting that there had been no regular independent evaluations of the program’s effects on TBI patients and their families. To address these concerns, HRSA contracted with the Institute of Medicine (IOM) in the spring of 2005 to conduct a study: (1) to assess the impact of the HRSA Program on how state systems are working or failing to work in support of individuals with TBI; and (2) to advise HRSA on how it could improve the program to best serve individuals with TBI and their families. The IOM appointed an 11-member Committee on Traumatic Brain Injury to perform the study.

This report presents the IOM Committee on Traumatic Brain Injury’s assessment of the HRSA TBI Program’s impact and recommendations for improving the program. The committee’s key findings and recommendations are summarized in Box ES-1 through Box ES-4.

APPROACH TO THE STUDY

This study is not intended as a technical evaluation of the HRSA TBI Program’s impact on either the delivery of TBI-related services or on person-level outcomes—such an analysis is not feasible given currently available data. Rather, the study’s focus is on whether the TBI Program has led to an expansion in state systems infrastructure as a precondition for better serving persons with TBI and their families.

The committee used a qualitative method to assess the program’s impact. Qualitative methods are often used to investigate developing institutions and systems as well as to assess the impact of government programs. Data were gathered from a variety of sources and were analyzed for key themes and recurring issues. Primary sources of data included semi-structured interviews with TBI stakeholders in seven states and representatives of selected national organizations, research literature and TBI program materials, and relevant survey data.

Clearly, HRSA should develop a more complete evaluation strategy to

|

BOX ES-1 Many people with TBI experience persistent, lifelong disabilities. For these individuals, and their caregivers, finding needed services is, far too often, an overwhelming logistical, financial, and psychological challenge. The committee finds that the quality and coordination of post-acute TBI service systems remains inadequate, although progress has been made in some states.

|

assess whether individuals with TBI have benefited from the HRSA Program. Many federal agencies require significant improvements in their evaluation information and capacity, according to OMB and the U.S. General Accountability Office (GAO). The committee suggests that HRSA follow GAO’s approach to building evaluation capacity in government agencies. GAO recommends four essential elements for a government-based evaluation infrastructure: (1) a culture of evaluation made evident through routine evaluations of how well programs are working to achieve agency goals; (2) quality data that are credible, reliable, and consistent; (3) analytic expertise in both technical methods and the relevant program field; and (4) collaborative partnerships with program partners or sister agencies to leverage resources and expertise.

|

BOX ES-2 FINDING: The committee finds that the HRSA’s TBI State Grants Program has produced demonstrable, beneficial change in organizational infrastructure and increased the visibility of TBI—essential conditions for improving TBI service systems. There is considerable value in providing small-scale federal funding to motivate state action on behalf of individuals with TBI. Whether state programs can be sustained without HRSA grants remains an open question.

|

OVERVIEW OF THE HRSA TBI PROGRAM

The organizational home of the program is HRSA’s Maternal and Child Health Bureau (currently in the Division of Services for Children with Special Health Care Needs). Since FY 2003, the annual federal appropriation for the HRSA TBI Program has been in the range of $9.3 to $9.5 million. The program is dwarfed within its parent agency HRSA, which had a $7.37 billion budget in FY 2005 and operates five different bureaus and 11 special offices.

RECOMMENDATION: The committee recommends that HRSA continue to support and nurture the program.

|

Grants Provided Under the HRSA TBI Program

As noted earlier, the HRSA TBI Program encompasses two grant programs: (1) the TBI State Grants Program; and (2) the Protection and Advocacy for TBI (PATBI) Grants Program.

TBI State Grants Program. HRSA’s mandate under the Traumatic Brain Injury Act of 1996 was to implement a program of federal grants to states, U.S. territories, and the District of Columbia to help them improve their

|

BOX ES-3 FINDING: The committee finds that it is too soon to know whether HRSA’s 3-year-old PATBI Grants Program has meaningfully improved circumstances for people with TBI-related disabilities. Nevertheless, PATBI Grants have led to new and much-needed attention to the protection and advocacy (P&A) concerns of people with TBI-related disabilities and their families.

RECOMMENDATION: The committee recommends that HRSA continue to fund the PATBI Grants Program.

|

TBI infrastructure and service systems for meeting the post-acute needs of individuals with TBI and their families. Since FY 1997, HRSA has competitively awarded three types of TBI State Program Grants to states, territories, and the District of Columbia: Planning Grants, Implementation Grants, and Post-Demonstration Grants.

In FY 1997 and FY 1998, the first 2 years of the TBI State Grants Program, grants were available as 1-year demonstration project awards. Depending on its existing TBI infrastructure, a state could apply for either a Planning Grant to help build the necessary infrastructure for a coordi-

|

BOX ES-4 FINDING: The committee finds that the management of the TBI Program is inadequate to assure public accountability at the federal level and to provide strong leadership to help states continue their progress toward improving systems for persons with TBI and their families.

RECOMMENDATION: The committee recommends that HRSA lead by example—that it instill rigor in the management of the HRSA TBI Program and build an appropriate infrastructure to ensure program evaluation and accountability. Thus, the committee recommends that HRSA do the following:

|

nated TBI service system or an Implementation Grant to execute various program implementation activities.

Planning Grants of $75,000 per year for states to establish the four core capacity components of a TBI infrastructure were available for up to 2 years. A state was eligible for a Planning Grant if it had an established plan for developing the four core capacity components of a TBI infrastructure (Box ES-5).

Implementation Grants of up to $200,000 per year were available for up to 3 years. States were eligible to apply for such grants if they had evidence that the four core capacity components of a TBI infrastructure were already in place. These grants were designed to encourage states to execute various program implementation activities, including carrying out the state’s TBI action plan, programs to address identified needs, and initiatives to improve access.

Post-Demonstration Grants were established by HRSA following the reauthorization of the HRSA TBI Program in the Children’s Health Act of

|

BOX ES-5 While the terms and available funding for TBI State Program Grants have evolved, the four core components of a state TBI infrastructure required by HRSA have not changed:

SOURCE: HRSA Program Guidance, 1997–2005. |

2000. These are 1-year grants of up to $100,000 intended to advance states’ efforts to build state-level TBI service capacity. A state must have satisfactorily completed an Implementation Grant to be eligible for a Post-Demonstration Grant.

Protection and Advocacy for TBI (PATBI) Grants Program. In the Children’s Health Act of 2000, Congress reauthorized the HRSA TBI Program and broadened HRSA’s mandate under the program. The 2000 act directed HRSA to implement a program of federal grants to protection and advocacy (P&A) systems in states, U.S. territories, and the District of Columbia to provide information, referrals, and advice; individual and family advocacy; legal representation; and specific assistance in self-advocacy for individuals with TBI and their families.

In FY 2002, the first year of the PATBI Grant Program, HRSA competitively awarded $1.5 million in grants to federally mandated P&A systems for people with disabilities. P&A systems in states and the District of Columbia were eligible for $50,000 PATBI Grants; those in U.S. territories and the American Indian Consortium were eligible for $20,000 grants.

In FY 2003, Congress doubled federal appropriations for the PATBI Grants Program to $3 million, and the grants became formula-based. Currently, therefore, all states, territories, and the District of Columbia receive PATBI Grants, with annual allotments ranging from $50,000 to $117,000 (California).

Administration of the HRSA TBI Program

The HRSA TBI Program has just one full-time staff position (program director), and four different people have held the position since 1997. Many of the administrative duties of the HRSA TBI Program are the responsibility of the TBI Technical Assistance Center (TBI TAC).

TBI TAC is in essence HRSA’s de facto TBI program staff. Its activities include general technical assistance to program grantees and applicants; an e-mail listserv that allows grantees and other participants to post inquiries, disseminate funding announcements, share best practices, and other program materials; a voluntary benchmark initiative; an online database, the “TBI Collaboration Space,” for grantees and others affiliated with the TBI Program; as well as national meetings and webcasts.

Since 2002, TBI TAC has been operated under a contract between HRSA and the National Association of State Head Injury Administrators (NASHIA).1 NASHIA is the national membership association for state TBI

program officials and other individuals concerned with state and federal brain injury policy.

EPIDEMIOLOGY AND CONSEQUENCES OF TRAUMATIC BRAIN INJURY—AN INVISIBLE DISABILITY

Data on the epidemiology of TBI have limitations because they draw primarily from hospital and emergency department records and do not include individuals who sustain TBIs and are seen in doctor’s offices or not treated for their injuries. It is known, however, that TBI is a leading cause of death and disability in the United States.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that at least 1.4 million TBIs occur in the United States annually, and 80,000 to 90,000 individuals per year sustain a TBI with long-term, often lifelong implications. At a minimum, CDC estimates, 5.3 million Americans have a TBI-related disability.

Individuals who sustain a TBI are a heterogeneous group, including the very young, the very elderly, as well as adolescents and young adults. Although many individuals with TBI were robust and healthy prior to their injury, others may have had one or more preexisting conditions that put them at risk.

From 1995–2001 the leading causes of TBI were falls (28 percent), motor vehicle accidents (20 percent), struck by/against (19 percent), and assaults (11 percent); these accounted for three-fourths of TBI-related emergency department visits, hospital stays, and deaths. TBI often goes undetected among high school, college, and professional athletes.

TBI has become a signature wound of the current Iraq war, largely because soldiers are increasingly exposed to improvised explosive devices and protected by improved military armor. Helmets cannot prevent the internal bleeding, bruising, and tearing of brain tissue that result from exposure to blasts.

The majority of people who sustain a TBI are mobile and able to care for themselves after a TBI, but physical health problems are common. Such problems include balance and motor coordination, fatigue, headache, sleep disturbance, seizures, sensory impairments, slurred speech, spasticity and tremors, problems in urinary control, dizziness and vestibular dysfunction, and weakness.

Typically, TBI-related cognitive problems and behavioral impairments have more impact on a person’s recovery and outcome than physical limitations. Cognitively impaired persons with TBI may experience problems in concentrating, remembering, organizing their thoughts, making good decisions, solving everyday problems, and planning and foresight. They may be

easily confused or forgetful. Their language skills, both written and spoken, may also be impaired. Some individuals with TBI may find it hard to learn new information or interpret the subtle cues and actions of others. As a result, they may act or speak inappropriately.

Furthermore, a substantial literature documents that TBI increases the risk of major depression, general anxiety disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, panic disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, anti-social behavior such as criminality and substance abuse, and suicide. Individuals with TBI with preexisting behavioral and psychiatric problems may find that the brain injury exacerbates their condition and makes the management of day-to-day function all the more complex and difficult.

It is difficult to capture the impact of TBI on an individual’s every day existence. Data collection and analysis are daunting challenges given the fragmented nature of TBI services and the inflexibility of their disparate data systems, lack of standardized definitions, and multiple public and private service systems.

Nevertheless, substantial proportions of individuals with TBI report persistent limitations in activities of daily living, ability to return to work, social skills, relationships, and community participation.

Family caregivers of individuals with TBI-related disabilities may have to radically change their lives to meet their loved ones’ long-term needs and financial burdens. Most families are not equipped to care for someone with the cognitive deficits and behavioral and emotional changes that are characteristic of severe TBI and often suffer substantial stress. As a result, the emotional and physical health status of family caregivers can be as compromised as that of the person with the TBI. In addition, there is evidence that TBI places a substantial burden on an array of social institutions and systems such as psychiatric facilities, courts and correctional facilities, schools, and disability and welfare programs.

SERVICE NEEDS AND SOURCES OF FUNDING AND OTHER SUPPORTS FOR PEOPLE WITH TBI-RELATED DISABILITIES

For TBI survivors with disabilities, insurance coverage of acute and post-acute services may be limited both by the type of services and by the intensity and duration of services. Coverage of behavioral health services and cognitive and physical rehabilitation is often restricted or not available at all. Focused surveys and qualitative research show that some TBI survivors have persistent unmet needs long after the acute crisis of their injury.

Finding needed services is typically a logistical, financial, and psychological challenge for family members and other caregivers, because few coordinated systems of care exist for individuals with TBI. People with TBI-

related disabilities often require access to diverse services including case management, health care services, cognitive and physical rehabilitative therapies, behavioral health care services, family and caregiver supports, vocational rehabilitation, housing, and transportation services. Eligibility criteria for services and supports are often confusing and exclusionary—access to funding and supports is often driven by nonclinical variables, such as family income, health coverage, geography, and other socioeconomic factors that may change over time. Many families may not even know what is available.

Given the array of services that may be necessary for a given individual with TBI-related disabilities, the absence of coordinated systems of care for individuals with TBI-related disabilities is a major problem for many persons with TBI and their families. It is easy for them to get lost, depressed, or desperate. Guidance of persons with TBI and their families through multiple potential sources of care through public and private agencies and system coordination is a prima facie essential condition for adequate service.

The principal sources of funding and support for TBI services are Social Security Income (SSI), Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI), Medicaid, and Medicare. Eligibility for SSI and SSDI is often the critical path to Medicaid- or Medicare-sponsored health coverage. For low-income persons, eligibility for a Medicaid long-term home and community-based waiver may be the only means to essential services such as personal care, homemaker services, and transportation. Several programs administered by the Office of Special Education and Rehabilitation Services in the U.S. Department of Education also provide critical supports: Independent Living Services, Vocational Rehabilitation, and Protection and Advocacy for Assistive Technology. Although there is only limited information documenting how well these programs cover the post-acute needs of persons with TBI, it is well established that there is a substantial discrepancy between needs and adequacy of funding for essential services.

ASSESSING THE HRSA TBI PROGRAM

Since the implementation of the HRSA TBI Program in 1997, there has been demonstrable improvement in two essential preconditions for improving TBI service systems—state-level TBI systems infrastructure and the overall visibility of TBI have grown considerably.

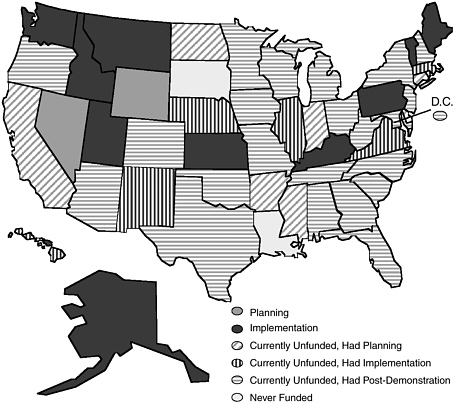

Almost all states have demonstrated interest in expanding their capacity to serve individuals with TBI (Table ES-1). All but two states (Louisiana and South Dakota) have applied for and received at least one TBI State Program Grant from HRSA (Figure ES-1). Many states have successfully completed Planning and Implementation Grants. As of 2005, 37 states had received Planning Grants; 40, Implementation Grants; and 23, Post-

TABLE ES-1 Number of States Participating in HRSA’s TBI State Grants Program, by Type of Grant, 2005*

FIGURE ES-1 Traumatic brain injury program grants by state, 2005.

SOURCE: TBI TAC, 2005.

Demonstration Grants.2 Twelve states were in the midst of a Planning or Implementation Grant.

The committee is impressed with what has been done and rates the HRSA TBI Program overall a success. There is considerable value in providing small-scale federal funding to catalyze state action. Nevertheless, substantial work remains to be done at both national and state levels.

So far, the HRSA experience shows that no two state TBI programs have evolved in the same way. Not surprisingly, states with established leadership, interagency cooperation, and/or CDC-sponsored TBI data collection have been better positioned to use the TBI grants from HRSA more quickly and effectively than other states. Yet serendipity also plays a part; there is no substitute for having an influential policy maker who champions the TBI cause.

The committee believes that the management and oversight of the HRSA TBI Program have been inadequate. To date, perhaps because of insufficient resources, HRSA has not built the infrastructure necessary for a systematic review of the TBI Program’s strengths and weaknesses or the state grantee evaluations and final reports that HRSA requires. HRSA has shown only token attention to evaluation of the state grantees or the TBI Program itself. The states are ill equipped to conduct technical evaluations and require constructive guidance in this area.

Thus far, the HRSA TBI State Grants Program has been handled as a grant program designed to establish four core organizational and strategic components in each state but to allow considerable state variation. This approach was realistic in two ways: (1) by recognizing the different bases on which improvement might take place in different states (some already organized for TBI, others not); and (2) by encouraging entrepreneurship and innovation. TBI TAC has provided valuable assistance as an information base and a spur for diffusion of innovation across the states.

The committee concludes that it is too soon to know whether the 3-year-old PATBI Grants Program has meaningfully improved circumstances for persons with TBI. State P&A systems have begun to focus on TBI, significantly for the first time. HRSA should collect data on P&A TBI-related activities in order to evaluate the impact of the PATBI Grants. HRSA should also ensure that persons with TBI and their families are aware of P&A services in their communities.

The committee urges HRSA to exercise strong leadership on behalf of the state grantees. Indeed, the program should embody many of the characteristics it demands of the grantees. It should serve as a national information resource on the special needs of individuals with TBI, keep track of

emerging issues in state TBI programs, and disseminate information on best practices. It should also advocate for the TBI grantees, by, for example, pressing sister federal agencies to furnish needed data and to address TBI in eligibility rules for other federal programs.

Further progress in TBI systems and services will be elusive if HRSA does not address the program’s fundamental need for greater leadership, data systems, additional resources, and improved coordination among federal agencies. It is worrisome that the modestly budgeted HRSA TBI Program continues to be vulnerable to budget cuts. The states are now at a critical stage and will need continued federal support if they are to build an effective, durable service system for meeting the needs of individuals with TBI and their families. The HRSA TBI Program should be a priority for HRSA.