APPENDIX E

Stakeholders Assess the HRSA TBI Program: A Report on National Interviews and Interviews in Seven States

Holly Korda, M.A., Ph.D.

Health Systems Research Associates

Chevy Chase, Maryland

Stakeholder interviews were conducted during the summer of 2005 in a sample of seven states: Alabama, California, Colorado, Georgia, New Jersey, Ohio, and Washington State. These states were selected to provide a cross section of state and program characteristics including: length of participation in the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) Grant Program; maturity of the state’s Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) program infrastructure; state funding levels and mechanisms such as Medicaid waivers and TBI trust funds; lead agency location in state government; program accomplishments; data availability; presence or absence of other programs, e.g., TBI Model Systems, TBI surveillance, and others; and geographic and cultural diversity. The Institute of Medicine (IOM) staff consultant conducted telephone interviews in Alabama, California, New Jersey, Ohio, and Washington State. The committee chair, study director, and staff consultant participated in 2-day site visits to conduct in-person interviews with stakeholders in Georgia and Colorado.

Study respondents in each state were selected based on criteria developed by the IOM Committee, and include: TBI lead agency representative, protection and advocacy (P&A) system representative, state brain injury association representative, consumer or family member of an individual with TBI, lead injury prevention representative, and other stakeholder rep-

Report submitted to the IOM Committee on Traumatic Brain Injury in fulfillment of consultant contract agreement, November 13, 2005.

resentatives of key state agencies, TBI trust funds, Medicaid waivers, and related interests. State TBI lead agency representatives helped to identify appropriate representatives to be contacted in their states. National program stakeholders involved with the HRSA TBI Program were also contacted for interviews, including the HRSA TBI Program Director; Executive Director of the National Association of State Head Injury Administrators/Director of the TBI Technical Assistance Center (TBI TAC); President/CEO of the Brain Injury Association of America; and Executive Director of the National Disability Rights Network (formerly the National Association of Protection and Advocacy Systems, Inc.).

Interviews were conducted using a semi-structured interview guide developed by the IOM Committee to address areas of importance relating to state program implementation; program impact on persons with TBI and their caregivers; and coordination of TBI-related services, including education, vocational rehabilitation, employment, housing, transportation, and mental and behavioral health care. The interview guide includes questions about each state’s history of TBI service delivery, and their experiences with each of the HRSA TBI Program grants:

Planning grants allow states to build infrastructure through the TBI Program’s four core components—(1) establishing a TBI Statewide Advisory Board, (2) identifying a Lead Agency, (3) conducting a Needs and Resources Assessment, and 4) developing a TBI State Action Plan.

Implementation Grants allow states to undertake activities, e.g., implementation of the State Action Plan or activities to address identified needs, to improve access for individuals with TBI and their families.

Post-Demonstration Grants authorized by the Children’s Health Act of 2000 have been available to allow states that have completed 3 years of implementation to support specific activities that will help states build TBI capacity.

Protection and Advocacy Systems Grants allow 57 states, territories, and the Native American Protection and Advocacy Project to assess their state P&A Systems’ responsiveness to TBI issues and provide advocacy support to individuals with TBI and their families.

The interview guide also includes questions about states’ experiences with the TBI Technical Assistance Center and with the HRSA TBI Program grant structure and processes. Each interview was approximately 40–50 minutes in length.

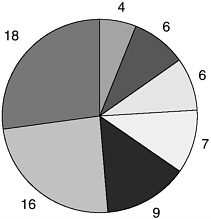

Stakeholders of the HRSA TBI Program interviewed for this study are represented by category in Figure E-1. Interviews were conducted with a total of 66 TBI stakeholders, including: national program directors (n=4), state brain injury associations (n=6), state injury prevention epidemiolo-

FIGURE E-1 TBI study respondents.

gists and staff (n=6), consumers with TBI or family members (n=7), state lead agency representatives (n=9), protection and advocacy systems staff (n=16), and others, including state agency and provider representatives (n=18).

STAKEHOLDER INTERVIEW SUMMARY AND KEY FINDINGS

I. TBI Grant History and Program Background

State TBI grantees differ widely with regard to availability of human and organizational resources, historical context, and political leadership and commitment to TBI—all factors that appear to be related to their abilities to leverage HRSA TBI Program funding for TBI services and systems coordination.

States with established, well-supported services and supports have been more successful leveraging HRSA funding than states with limited or no resources. States submitted grant applications to the HRSA TBI Program with different histories and resources for TBI services coordination and systems development. The HRSA grants to states have been competitively awarded since the first grant cycle in 1997. During the first 2 years of the HRSA TBI Program, Planning and Implementation grants were available as 1-year demonstration project awards. During these start-up years, as states and the HRSA Program gained experience with these grants, it became clear that longer funding cycles were needed to accomplish grant expectations. Funding availability for Planning grants

was subsequently expanded to 2 years, and Implementation grant funding was expanded to 3 years. After reauthorization of the Federal TBI Program in 2000, Post-Demonstration grants were introduced and became available, as 1-year awards. The HRSA TBI grants to P&As were added and awarded as 1-year competitive grants in 2002. The following year, the P&A grants were changed to formula-based awards. In August 2005, the HRSA TBI Program introduced new, 3-year Partnership Implementation grants that replace HRSA’s other TBI grant programs to states. Planning grants were $75,000 for up to 2 years, Implementation grants have averaged $250,000 over 3 years, and Post Demonstration grants have averaged $100,000 over 1 year. The P&A grants start at a base average of $50,000 per year. The new Partnership Implementation grants are limited to $100,000 per year for a 3-year period.

Grant histories for the seven study states are summarized in Table E-1, below.

California, Colorado, Georgia, and Washington State had none of HRSA’s four core TBI Program components in place when they received their first grant awards. Colorado and Georgia reported previous, established programs for individuals with TBI in their states dating to the 1980s: Colorado’s federally-funded Rocky Mountain Regional Brain Injury Center (RMRBIC) and the Georgia Department of Labor’s comprehensive programs developed at Roosevelt Warm Springs Institute for Rehabilitation

TABLE E-1 HRSA TBI Grants Program History: State Award Years

|

Grant Type |

Alabama |

California |

Colorado |

Georgia |

New Jersey |

Ohio |

Washington |

|

Planning |

— |

1999, 2001 |

1999 |

1997 |

— |

— |

2000, 2001 |

|

Implementation |

1997, 1998, 1999, 2000 |

— |

2001, 2002, 2003 |

1998, 1999, 2000 |

1999, 2000, 2001 |

1998, 1999, 2000 |

2003, 2004, 2005 |

|

Post-Demonstration |

2001, 2002, 2004 |

— |

2004 |

2004 |

2002, 2003, 2004 |

2002, 2003, 2004 |

— |

|

Protection and Advocacy |

2002, 2003, 2004, 2005 |

2003, 2004, 2005 |

2002, 2003, 2004, 2005 |

2003, 2004, 2005 |

2002, 2003, 2004, 2005 |

2002, 2003, 2004, 2005 |

2002, 2003, 2004, 2005 |

and its Vocational Rehabilitation programs. California and Washington State also noted early efforts to address TBI through their states. California’s Department of Mental Health established Caregiver Resource Centers and a TBI trust fund, in the 1980s. Washington State developed demonstration projects addressing the needs of individuals with TBI. Each of these states has also hosted TBI Model Systems,1 funded by the National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research (NIDRR). Colorado, Georgia and Washington State hosted Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Core Injury Programs. Still, none of the four states had developed a sustainable TBI infrastructure.

Each of these states applied for Planning grants to develop the HRSA TBI Program’s four core TBI program components. California applied for, but was not awarded, an Implementation grant. Washington is in its third year of its Implementation grant, and Colorado continued on to receive a Post-Demonstration grant after completing a 3-year Implementation grant.

Alabama, Ohio, and New Jersey were well under way with state efforts to coordinate services to individuals with TBI and their families when these states applied for HRSA grant funding. Alabama, which established its State Head Injury Program for adults in 1989 and designated its State Head Injury Task Force and a coordinator in 1990, applied for HRSA funding to expand its Interactive Community-Based Model for adults with TBI to create a children’s system. Ohio applied to the HRSA TBI Program with an established Advisory Council in place. The state’s collaboration with the Ohio Brain Injury Association led to development of a strategy to develop a comprehensive model service coordination continuum that would be expanded with HRSA funding. New Jersey had services with several state agencies, but did not have a coordinating group in state government. Preparing for its next grant application after two rejected attempts, the state moved to designate the Department of Human Services, Office of Disabilities as lead agency, as well as an interagency advisory board. New Jersey’s first grant involved collaboration with an established partner, the Brain Injury Association of New Jersey. Alabama and Ohio had established CDC Core Injury Programs, and all three states hosted NIDRR-funded TBI Model Systems. All three states were served by Rehabilitation Services Administration grants for TBI Regional Centers, with those centers actually awarded to programs in Alabama and Ohio. The Rocky Mountain Regional Brain Injury Center mentioned above was also a TBI Regional Center.

II. HRSA TBI Grant Experience

The seven study states used diverse approaches and met with varied results implementing their HRSA TBI Program grants. Key findings are summarized below.

Planning Grants

HRSA’s four core TBI program components—Lead Agency, Statewide TBI Advisory Board, Needs Assessment, and State Action Plan—have been embraced as helpful elements for coordination and collaboration around TBI at the state level.

Although some states have shifted agency placement and contacts since their start-up Planning grants, there is general agreement that these four components are helpful for moving TBI services and systems change forward. States have conducted Needs and Resources Assessments and developed State Action Plans, and have used this information to guide TBI efforts for the HRSA grant, as required by the HRSA TBI Program.

|

1. Statewide TBI Advisory Board: Requirement to develop or demonstrate the existence of a Statewide TBI Advisory Board within the appropriate health department of the state or within another department as designated by the state’s chief executive officer. The Board’s composition must include representatives of the involved state agencies; public and private nonprofit health-related organizations; disability advisory or planning groups; members of an organization or foundation representing individuals with TBI; state and local injury control programs if they exist; and a substantial number of individuals with TBI or their family members. |

The requirements for, and states’ experiences developing, the four core components of the HRSA TBI Program are described in the following section.

The four states that established TBI statewide Advisory Boards after receiving HRSA grants—California, Colorado, Georgia, and Washington State—identified two critical elements to this activity: having membership of a manageable size and including the right people as representatives. Stakeholders in each state struggled with these elements in building and, in some cases, rebuilding a board.

One respondent who served as a member of Georgia’s early Advisory

Board described it as “unwieldy, with 50–60 members.” Another added, “It’s hard to work with a group that large … They tried to do too much.”

Georgia’s Advisory Board held together through the state’s Planning and Implementation grants, but disbanded after its Post-Demonstration grant request was denied. The state established a Brain and Spinal Cord Injury Trust Fund and Commission in 1998. The Commission has 14–15 members, including some members of the re-established TBI Advisory Board. The new board is much smaller and is reported to be more focused.

Washington State also started with a large Advisory Board that has since been pared down. One respondent describes the challenges as “participation and coordination. People come and go. Forming a sustainable board was a challenge.” Defining its mission in the state was challenging, but important to the Board’s coming together as a group.

“We were also asking ourselves, were we here for the Planning grant or another, broader mission? The planning group, our planning activities, gave the Advisory Board a focus.”

In Colorado, where many key participants had established working relationships in the brain injury community predating the HRSA TBI Program, there were so many people who wanted to serve on the Advisory Board that people were turned away. This Board limited the number of participants from the start, facing the challenge of “making sure we had the right people at the table.”

Establishing an Advisory Board in California was complicated by the diversity of members as well as the state’s vast geography. One respondent described the Board as “initially very divisive, there was no common goal. People came to the table with different agendas, the community was divided.” With help from a skilled consultant the group did come to consensus on a State Action Plan, working through its differences. However, the Advisory Board disbanded after the state’s application for an Implementation grant was denied.

|

2. Lead Agency: Designation of a state agency and a staff position responsible for coordination of state TBI activities. |

Finding the most appropriate fit for a state lead agency is a key issue for states in the early stages of developing their state TBI programs. The TBI Technical Assistance Center (TAC) reports that throughout the history of the HRSA TBI Program, lead agencies have been located in at least nine different state agencies, including Public Health, Human Services, Social Services, Medicaid, Rehabilitation Services, Mental Health, Developmental Disabilities, and Education.

States often change lead agencies in search of an appropriate “home” for TBI in state government. Placement of the lead agency is closely tied to the political and programmatic leadership, commitment, and focus of the state’s TBI activities. Three of the four states that received Planning grants—California, Georgia, and Washington—changed lead agencies as they moved forward with their HRSA grants. California shifted its lead agency from Vocational Rehabilitation to the Department of Mental Health, although respondents in this state remain unclear why the agency remains in this location given the service needs of the state’s TBI clients and families. In Washington State the Vocational Rehabilitation agency served as the lead agency for the first two HRSA grant years, then determined that TBI was not its mission. Aging and Adult Services “agreed to take us on,” recalled one respondent. The state TBI program is now with Aging and Disability Services, which state respondents observe is a better fit.

Georgia designated the State Health Planning Agency (SHPA) as the lead agency for its Planning and Implementation grants, but the agency did not have the capacity or commitment to move the program forward. Georgia’s brain injury association urged the state to apply for a Post-Demonstration grant in 2002, and approached the Department of Community Health (DCH) to serve as lead agency. The application was denied. The DCH, which addressed numerous programs not related to TBI, approached the Brain and Spinal Injury Trust Fund Commission, a relatively young agency with a focus on TBI and asked the Commission to take over its role as lead agency in applying for a new Post-Demonstration grant. The Commission currently serves as Georgia’s lead agency and has made considerable progress building a Central Registry with its HRSA grant.

|

3. Needs and Resources Assessment: Statewide needs and resources assessment, with an emphasis on resources, completed or updated within the last five years, of the full spectrum of care and services from initial acute treatment through community reintegration for individuals of all ages having TBI. |

The four states that conducted Needs and Resources Assessments with their HRSA Planning grants did not have state-specific data about their states’ TBI population and needs, and used different approaches to identify needs and resources to inform their programs. The HRSA TBI Program, through TBI TAC, provides a forum for states to share information about the methods they use, and allows states to select and develop their own approaches. Information from the assessments provides the basis for states to develop the State Action Plan required as part of the TBI Program core.

Approaches used by the four sample states that developed Needs and Resources Assessments for their Planning grants are included below.

-

California used multiple methods to obtain information for their Needs and Resources Assessment, including provider and public assessments, public meetings, and extensive networking throughout the state.

-

Washington State conducted two assessments: one for providers, and an Internet-based assessment for families. One stakeholder recalls, “When DVR had this, there weren’t clear parameters about how to do a Needs Assessment,” suggesting that approved parameters for collecting information might help future grantees.

-

Colorado’s Needs and Resources Assessment included interviews with state agencies to determine their awareness of and involvement in TBI issues, and their perceptions of TBI needs and resources; in-depth interviews with providers; community forums; and printed questionnaires distributed to members of brain injury support groups.

-

Georgia developed and distributed surveys, conducted regional town hall meetings, surveyed case managers, and hosted a statewide Stakeholders’ Conference to determine concerns and service needs of TBI survivors and families.

|

4. TBI Statewide Action Plan: Development of a Statewide Action Plan to develop a culturally competent, comprehensive, community-based system of care that encompasses physical, psychological, educational, vocational, and social aspects of TBI services and addresses the needs of individuals with TBI as well as family members. |

TBI State Action Plans required by the HRSA TBI Program reportedly vary in both format and length. A TBI TAC respondent noted that the plans are difficult to compare state by state: some plans are brief, one-page lists of key issues and activities; others are lengthy, detailed documents. Most State Action Plans draw on information obtained in the Needs and Resources Assessment, but states also use other sources of information and Advisory Board deliberations to target priority areas for TBI services and systems development.

The TBI TAC has worked with several states to help them achieve more focus in their State Action Plans. As a technical assistance activity, the most difficult aspect of the State Action Plan is “getting grantees to understand the Action Plan is a living, breathing document,” as a TBI TAC respondent observed.

Often, states must refine or revisit their planning as resources and conditions in the state change. California reportedly made great strides pulling together different constituents in developing its State Action Plan, resulting in “a very democratic process … a very sensitive, comprehensive plan,” but “the bottom has dropped out without resources.” Washington State worked with TBI TAC after the state changed its lead agency, in an effort to refine the plan to a more manageable effort that was subsequently developed through the state’s Implementation grant.

Implementation Grants

Implementation grants are sometimes seen as a vehicle to maintain a state’s TBI infrastructure, and have been used to expand existing programs and initiate new projects, often by leveraging the state’s resources with partner organizations.

State respondents credit the HRSA TBI Program with providing the funding and political motivation to continue the focus on TBI through program and project development in areas not likely to be initially funded by the state. Partnerships with Brain Injury Associations, universities, and other organizations helped states leverage grant resources and professional expertise.

Six of the seven sample states received Implementation grants. These grants allow states to implement activities identified in their State Action Plans or other activities that address identified needs, to improve access for individuals with TBI and their families. Implementation grants were awarded for 1 year during the early years of the HRSA TBI Program. Following reauthorization of the TBI Act in 2000, these grants were extended to 3-year awards, a time frame seen as more appropriate to the scope of activities states addressed than the 1-year grants. One national respondent observed that states often “struggled deciding what to choose” as a focus of their Implementation grants, facing the need to maintain infrastructure as well as select from among many identified needs.

The sample states reported different experiences with their Implementation grants. California applied but was denied an award. A state respondent explained, “HRSA felt we were biting off too much. One of the problems we had was, we had priorities identified and picked out … [Federal requirements] didn’t fit well with the state’s priorities. [The application] wasn’t well put together when we tried to add on these requirements.”

Georgia applied for and received an Implementation grant after completing the four core components under its Planning grant. The state report-

edly achieved only modest success completing tasks proposed under the grant, with an ambitious agenda, changes in states government, and difficulties pulling together the Lead Agency and Advisory Board. Georgia’s TBI Advisory Board disbanded after the Implementation grant was completed. State respondents noted, “ there’s not much to show” for the grant.

New Jersey and Washington State involved strong partner organizations that enabled these states to leverage partners’ resources to address grant objectives. New Jersey entered the HRSA TBI Program after two applications had been denied, establishing its core TBI Program components during this downtime. The state received HRSA funding for its third application, an Implementation grant to develop the Supporting Families in Crisis (SFC) program in close partnership with the state brain injury association. The SFC focused on educating families and providers about TBI-related resources, increasing the numbers of minorities and non-English speakers who access services, and increasing the identification of children with TBI in schools. Washington State developed a strong collaboration with its TBI Model System, which worked with the P&A and other state agencies to develop TBI Tool Kits, videoconferences, and other materials. The TBI Model System shared board membership with the state’s TBI Advisory Board and was seen as “a natural partner … The Model System was doing good work with telehealth [videoconferences and distance learning], so there were good opportunities to get involved.”

Alabama, Ohio, and Colorado used their grants to build on and expand existing plans for TBI services development. Alabama received Implementation grant funding to develop a statewide pediatric service delivery model, PASSAGES, as an expansion of the state’s Interactive Community-Based Model for adults with TBI. Ohio did not receive funding for its first application, but was awarded funding for an Implementation grant the following year. Ohio’s grant focused on developing four Community Support Networks (CSNs) to add to two CSNs already established as part of the state’s comprehensive “Ohio Plan: Building Ramps to the Human Service System for People with Brain Injury.” Colorado worked closely with its state brain injury association and other stakeholders to continue Colorado Information, Resource, Coordination, Linkage, and Education (CIRCLE) programs that convened providers and stakeholders for information sharing and referral. Other grant activities included increasing availability of information statewide, addressing the needs of children with TBI through development of a training manual (BrainSTARS) and training materials for parents and school personnel, and increasing awareness of state agency personnel about brain injury and to identify and change barriers to effective service coordination.

Post-Demonstration Grants

States found the 1-year award cycle and the $100,000 funding cap on Post-Demonstration grants to be too short a time, and too limited in support for meaningful TBI projects. While some states were able to pilot projects that otherwise would not have been funded through the program, most respondents noted that these grants were difficult to develop and implement.

Post-Demonstration grants were added to the HRSA TBI Program following their authorization as part of the Children’s Health Act of 2000. These grants have been available to allow states that have completed three years of implementation funding to support specific activities that will help build state TBI capacity. Of the seven sample states, Alabama, New Jersey, and Ohio received three Post-Demonstration grants; Colorado and Georgia received one Post-Demonstration grant; and California and Washington State have not received the grants. Table E-2 shows Post-Demonstration grant projects funded in these states.

TABLE E-2 Post-Demonstration Grant Projects Funded in Sample States

|

Alabama |

2001: Identification, accommodation, referral of adolescents in schools to AL’s Service Linkage Program 2002: Education and outreach to providers and the public about psychiatric disorders and TBI 2004: Education and outreach about domestic violence and TBI |

|

New Jersey |

2002: Outreach to inner-city minority neighborhoods 2003: Development of social, recreational supports for individuals with TBI, in partnership with faith-based, other community organizations 2004: Education and outreach to state staff of One-Stop vocational support centers |

|

Ohio |

2002: Enhancement of collaboration between Advisory Board and Brain Injury Association of OH, to increase participant buy-in 2003: Hospital-based education and work with families of individuals with TBI 2004: Hospital-based education and work with families of individuals with TBI |

|

Colorado |

2004: Expansion of CIRCLE networks, training for parents and school personnel regarding children and TBI, continued efforts to increase TBI awareness among state personnel |

|

Georgia |

2004: Development of a Central Registry infrastructure, provision of accurate data on TBI for use in state policy development, development of statewide resource database to improve resource access for individuals with TBI and families |

Respondents in the five states that received Post-Demonstration grants noted that the grants had helped them develop TBI projects in new and underdeveloped areas—but most found it difficult to work within the grant’s time frames and funding limits. Respondents commented,

“The Post-Demonstration grants we’ve seen as helpful but also frustrating. One hundred thousand dollars is not much. There’s lots of preparation, paperwork putting together the application. It’s very labor intensive, for not much in funding.”

“The biggest challenge is that the grant period is too short. Make them longer than 1 year, or make the grants so you can build on past efforts, not just develop new ones. In one year you can barely establish the right contacts. Many communities see projects come and go, and you need to build trust in approaching and working with them. It takes more than a year. Two year grants, even if less money, would be better.”

“We appreciate the one year monies, but it takes more than a year to do [a project]. You need to link with people and at the same time identify what the grant was about. The year passed quickly.”

Protection and Advocacy System Grants

All Protection and Advocacy Systems provided legal advocacy for individuals with TBI before initiation of the HRSA P&A grants, and all reported increased attention to this population with receipt of HRSA funding. The P&As, like state grantees, vary in sophistication, capability, and capacity to serve individuals with TBI, and have directed their grant funding in different ways. The P&A stakeholders noted the importance of finding a balance between education and training within their own organization and in the community, and conducting individual advocacy to effect systems change. All P&As noted the challenges of addressing TBI with limited HRSA funding.

Protection and Advocacy system grants have been offered since 2002 to support states, territories, and the Native American Protection and Advocacy Project to assess their P&A systems’ responsiveness to TBI issues and provide advocacy to support individuals with TBI and their families. While states’ P&As are charged to keep watch over states’ policies and programs affecting individuals with TBI and other disabilities, all seven P&As in the sample states reported working closely with the state TBI grant program. Georgia’s P&A and state TBI program share an Advisory Board, and in Washington State, the state’s TBI Advisory Board meetings are held at the P&A offices.

P&A respondents used their HRSA grants to “raise the visibility of the P&A” as a provider of advocacy for persons with TBI, and looked for ways to leverage limited funding, starting at $50,000, to achieve this goal. Respondents reported providing education, outreach, and training about TBI within their own organizations, in the provider community and the public. A Washington State respondent explained

“Systemically, TBI was a new focus for us. We had no TBI focus before, although the P&A, like all P&As, has served people with TBI. The grant allowed us this focus … We receive a small amount of funding from HRSA at the P&A, so we asked ourselves, how could we get the biggest bang for the buck? We decided to fold a TBI focus into our other work. I am also on many community councils, and I bring a TBI focus to these as well. We leverage the money to get the most out of it.”

Respondents at Ohio’s P&A explained that, unlike most states’ P&As, their organization came to the HRSA Program with a long history working with TBI, and has served on the Ohio Brain Injury Committee since before the HRSA grant. This P&A was able to move quickly, without a learning curve, when HRSA P&A grants became available.

“When we got P&A dollars, had we not already developed a focus on systems through the HRSA state grants, we couldn’t have focused on children in special education … I can’t imagine HRSA sending funding to a state that didn’t have this background work in place, established. It takes years to understand the TBI population. We had the background, relationships, special education skills—so we were able to make things happen quickly, without having to learn the basics.”

The P&As in Colorado and Georgia used state assessments, planning documents, and other materials to help focus their P&A grants. Alabama’s P&A also notes they have been “involved from the outset” with the state’s TBI initiatives.

In California, where the state’s TBI Advisory Board is currently inactive, the P&A’s presence is of particular importance keeping some state attention on TBI. However, the P&A struggles to stretch funding with one dedicated TBI staff coordinating efforts for a 200-person organization across four regional offices.

“It’s great that California got the Planning grant, but there was and is no infrastructure to sustain it. There was no one with ‘juice’ in the administration to keep it going …

Successful states have high-level people in key positions to support TBI activity. It didn’t happen in California … What we [P&A] are trying to do is take what we have—we have eight members on our TBI Board, including five TBI survivors/family. The P&A is also asking why California doesn’t have a Medicaid waiver for TBI, to provide home and community care.”

III. TBI Service and Systems Coordination

States described a spectrum of service system coordination, collaboration, and fragmentation. Service coordination for individuals with TBI and their families often depends on program eligibility. States recognize the need to coordinate TBI-related services at both the individual and the systems level—as well as the need to develop basic services to coordinate.

States in the study sample described various service delivery arrangements for individuals with TBI and their families. States described varying levels of service coordination to help people navigate service systems, system coordination, and interagency collaboration. States that entered the HRSA TBI Program with a history of collaboration and efforts to coordinate services prior to their involvement with HRSA were able to build on this foundation with their HRSA grants. Alabama described a statewide network for individuals with TBI that built on the state’s Interactive Community-Based Model, a decentralized approach to provide community services integration in local communities first piloted in the early 1990s. Ohio also developed its TBI services networks from efforts in the 1990s to develop “The Ohio Plan,” a model envisioning Community Support Networks in local areas, a statewide Helpline and Information Clearinghouse, and individualized resource facilitation services. Washington State, which used its HRSA funds to begin establishing a basic infrastructure for TBI, described fewer resources, services coordination limited to individual programs, and little or no systems coordination. State descriptions of TBI service and systems coordination are shown in Table E-3, below.

Medicaid Waivers

Medicaid programs in several states provide substantial support for individuals with TBI and their families through TBI-specific and generic waivers for home and community-based services. As TBI becomes more visible among providers and communities, demand for waiver slots is reportedly increasing. Eligibility and availability of slots are common barriers to access.

Several states use Medicaid waivers to provide community-based services, rehabilitation, or long-term support for individuals with TBI. Colorado and New Jersey have established Medicaid waivers specifically for individuals with TBI. Georgia, Washington State, and Ohio provide services to individuals with TBI through Medicaid waivers for aged or disabled individuals for which they may qualify. “Many states think waivers solve the problem,” a national respondent stated, noting that “Medicaid

TABLE E-3 TBI Services and Systems Coordination in Study States

|

Alabama |

AL has an established core service delivery network—the Interactive Community-Based Model (ICBM)—that uses care coordinators to help individuals with TBI and their families access services and supports across state agencies and organizations. The TBI registry is part of this system, allowing identification and followup of individuals who sustain TBI. The adult ICBM was first piloted in the early 1990s. |

|

California |

Services are formally coordinated through seven sites administered by the CA Department of Mental Health. The sites offer an umbrella of services and are listed on a state-sponsored web site. The sites serve limited numbers of clients; coordination does not occur outside these sites. Services are not provided for children. Little is known about the independent services used by individuals served outside these sites. The sites demonstrate diverse approaches to service delivery and coordination; two are hospital-based, while the other five are community-based. |

|

Colorado |

CO has an array of services for persons with TBI and their families, especially in the Denver area. CIRCLE networks established with the brain injury association operate regionally and allow local areas to identify and collaborate regarding needs and resources. Information and training statewide is conducted on issues including children and TBI. The state also provides some housing slots for persons with TBI. CO has a large Medicaid TBI/Acquired Brain Injury (ABI) waiver and a TBI Trust Fund that can be used for services support. |

|

Georgia |

Services are not currently coordinated across programs or agencies, and information about service availability in the state is lacking. Georgia is currently updating its Needs and Resources Assessment and State Action Plan to identify agencies and services needed and available to serve persons with TBI and their families, and opportunities that may exist for coordination. |

|

New Jersey |

NJ’s TBI-related services operate through informal collaboration and are not formally coordinated. When services are coordinated, it is through a specific program, e.g., Medicaid, which includes case management as part of the Medicaid TBI waiver. State services are available through generic disability programs. |

|

Ohio |

OH uses the Community Services Network (CSN) model outlined in “The Ohio Plan” to coordinate services for persons with TBI and their families in four service areas where CSNs have been established. Other areas of the state are not served by the CSNs. A statewide database for information and referral is available to facilitate service access. There is no single point of entry. Service coordination is reportedly “haphazard,” depending on which agency provides service, what benefits are provided, which door one comes through. Generic Medicaid waivers are available for individuals with TBI who meet eligibility requirements. |

|

Washington |

Many people reportedly receive in-home services in WA. The Seattle area is location to a cluster of facilities with services for persons with TBI, including University of Washington’s Harborview Hospital, but Seattle-based services are not readily accessible to the state’s rural residents. Community-based services are difficult to access in urban and rural areas. There is no coordination of services unless an individual is enrolled as a participant in a specific program that offers case management or related services. |

waivers serve small numbers.” A summary of Medicaid waiver programs in study states in shown in Table E-4, below.

Colorado respondents noted increased demand for TBI waiver slots as TBI has increased its visibility as an issue. Whether and to what extent the HRSA grant may contribute to this increase is not clear. One state respondent reported, “In FY1997/98, at the beginning of the waiver, we had 143 clients. For FY 2003/04 we have 366 clients reported. Waiver costs increased from $1.46 million to $8.89 million [from FY1997/98 to FY2003/04] … I don’t really know why. I can’t say one way or the other if it is related to the HRSA grant.”

The P&As in states with Medicaid waivers reported that their cases involving persons with TBI often addressed availability and access to state

TABLE E-4 Medicaid Waivers Serving Individuals with TBI in Study States

|

State |

Year Established |

Amount |

Description |

|

Colorado |

1995 |

$5.2 million |

|

|

Georgia |

|

GA does not have a TBI-specific waiver, but 30 slots in the Independent Care waiver are set aside for persons with TBI. |

|

|

New Jersey |

1993 |

$14.6 million |

|

|

Ohio |

|

Medicaid waivers can be used for eligible persons with TBI. |

|

|

Washington |

Persons with TBI can use the state’s Aging and Disabilities waiver, based on functional abilities rather than diagnosis. |

||

waivers. In Ohio, the P&A developed a model waiver and has played a key role advising the state on related issues.

TBI Trust Funds

Trust Funds are seen as an effective way for states to access funds for TBI services. The substantial resources marshaled through these vehicles can provide strong leverage for TBI services and systems. Study states have TBI trust funds that direct funding for individuals, program support, or both. Stakeholders in trust fund states emphasized the importance of these funds for supporting their TBI-related efforts.

Five of the sample states—Alabama, California, Colorado, Georgia, and New Jersey—have established TBI trust funds using penalties or surcharges on traffic violations. These trust funds generate annual funds ranging from $1.1 million in California to $3.4 million in New Jersey. Three of the funds predate the state’s involvement with the HRSA Program. Colorado and New Jersey established their funds during participation in the HRSA Program. A summary of TBI trust funds in sample states is shown in Table E-5, below.

Some states used trust fund dollars to expand or sustain initiatives identified and implemented with HRSA grant funding; others targeted funds to support services for individuals. In New Jersey, trust fund dollars administered by the Division of Disability Services were used to continue mentor and training programs developed with HRSA funding. Alabama also used trust fund dollars to continue care coordination activities developed for its HRSA-funded children’s program. Georgia’s trust fund is administered by the Brain and Spinal Cord Injury Trust Fund Commission, which oversees development of the state’s Central Registry and provides support for services to individuals, to a cap of $5,000 annually per recipient.

Trust funds can be a powerful tool to help states support their TBI programs and services, but not all states are able to establish them. “Many stars need to align” for a state to establish a trust fund, observed a national respondent, “and the politics are complex.”

TBI “Special” Populations

Respondents in every state named TBI populations that were difficult to reach and serve. These populations include cultural and ethnic minorities, non-English speakers, rural residents, and individuals with coma or neurobehavioral conditions.

TABLE E-5 TBI Trust Funds in Study States

|

State |

Year Established |

Amount |

Description |

|

Alabama |

1993 |

$1.2 million |

The Impaired Driver’s Trust Fund is supported through fines on DUI convictions @ $100 per conviction. A portion of the revenues is used to support the TBI registry; remaining funds provide direct or purchased services. The fund supported information and referral for 678 individuals, and services for 1,359 individuals. |

|

California |

1988 |

$1.1 million |

The TBI Trust Fund is supported by 66% of State Penalty Fund revenues from vehicle code violations. Approximately $950,000 was used to provide services to 622 persons in FY2001; a portion was used for personnel costs and evaluations. Another portion was used to draw down $620,000 in federal vocational rehabilitation funds, serving 30 persons. |

|

Colorado |

2002 |

$2.5 million |

The TBI trust fund legislation imposes $10 and $15 surcharges for certain traffic convictions, requires 5% of funds be used to educate parents, educators, non-medical professionals in identifying TBI and assisting persons to seek proper medical care; 65% for services; 30% for research to promote understanding and treatment of TBI. |

|

Georgia |

1998 |

$2.3 million |

The Brain and Spinal Cord Injury Trust Fund is supported by a 10% surcharge on fines for driving under the influence (DUI). The commission distributes just over $2 million per year to individuals with TBI in awards of up to $5,000 per person. |

|

New Jersey |

2002 |

$3.4 million |

The TBI Trust Fund was established by statute and is funded by a $.50 surcharge on motor vehicle registrations. Funds can be used for services or program support. |

States and P&A respondents identified several subgroups of the TBI population as difficult to reach and serve. Cultural and ethnic minorities of all backgrounds, non-English speakers, and rural residents were named most frequently, followed by individuals with coma or neurobehavioral conditions, who typically reside in institutions. Respondents in Washington

State and Colorado also identified Native Americans in their states among those difficult to reach and serve.

Both states and P&As have initiated activities to reach out to these populations, with varying success. All respondents agreed that the needs are great and often unknown in these under-represented groups.

New Jersey undertook efforts to develop social and recreational supports in minority neighborhoods in the Camden area as a followup to its first Post-Demonstration grant. Respondents from the state and its partner brain injury association soon agreed that establishing community relationships in these neighborhoods involved more time—and trust—than they anticipated. One respondent recalled, “We found recreation was not a priority for the partners, the churches in Camden … programs like food pantries, shelters … were important to them.” The project re-designed its objectives, working through local churches.

In Alabama, a state respondent identified Spanish speakers from Mexico as a population in need of special outreach, but also recognized the challenges of reaching out to this group. This respondent commented that efforts to increase consumer involvement in the state’s minority communities have been difficult, even among native English speakers, noting that “[the state program] has not had as much consumer involvement from the African American population” as they’d like.

Services Difficult to Access for Individuals and Families with TBI

Despite differences in states’ TBI infrastructure and resources, respondents in every state named services that are difficult for individuals with TBI and their families to access. Respondents named housing, vocational services, and services for individuals with neurobehavioral disorders most frequently as difficult to access services.

Services not covered by public and private insurance, including nonmedical social and post-rehabilitation community support, were mentioned most frequently as services difficult for individuals and families with TBI to access. In addition to housing, vocational services, and neurobehavioral healthcare, respondents listed transportation, service coordination, and access to waiver slots as difficult to access services. One family member spoke to the needs of family caregivers, and placed hiring adult sitters and day care at the top of her list:

“Hiring sitters is the hardest thing. It is not covered by insurance. All of us who are caregivers need help with this. [My son] goes to Adult Day Care at the YMCA, and he’s there with people who are developmentally

disabled … his dad and I both work … He’s never alone, I can’t leave him by himself.”

Another consumer respondent emphasized the importance of insurance coverage in providing service access for persons with TBI and their family members, noting, “Medicaid provides options, private pay does … but others have a hard time.”

IV. TBI Data, Monitoring, and Evaluation

Data about TBI and TBI-related services in the study states are limited. Some state agencies collect data and track service utilization among individuals with TBI, but none of the study states reported comprehensive, cross-agency data monitoring. Several study states have established registries, which vary in scope and application, and some have conducted TBI surveillance with grant support from CDC. Respondents named lack of funding and expertise for data activities, as well as the challenges of how to monitor services and outcomes as obstacles to data-related activities.

TBI Data Collection in Study States

Registries and surveillance systems are the primary sources of TBI data in most states. Typically, injury prevention professionals in state health departments maintain and report these data, and report summary findings to state TBI Advisory Boards. States that do not conduct TBI surveillance rely on national estimates prepared by CDC.

Registries and surveillance systems vary widely across states. According to an injury prevention specialist in one sample state, there is much confusion in the field about “what constitutes a ‘Registry’ and a ‘Surveillance System,’” and the terms are often used interchangeably. This respondent explained, “Registries usually have contact information … Surveillance is usually a data system without contact information, and is used to identify risk factors.”

In practice, not all registries are used to contact individuals, and the quality and comprehensiveness of state survey data are not uniform across states.

Registries. Three of the seven study states—Alabama, Georgia, and Washington State—have established TBI registries, and a fourth state, New Jersey, is involved in efforts to create a combined TBI/Spinal Cord Injury

(SCI) registry. These registries were developed using different approaches and are used in various ways.

-

Alabama’s registry was established with the passage of the Alabama Head Injury and Spinal Cord Injury Registry Act in 1998, which requires hospitals to submit their data to the state. While respondents provided differing assessments about the comprehensiveness of the registry data, state TBI program staff report having successfully integrated the registry as part of Alabama’s TBI services system, enabling followup of newly identified TBI cases.

-

Georgia established its Central Registry for spinal cord injury in 1981, and expanded the Registry to include TBI in 1985. Expansion of the Central Registry has been the focus of the state’s 2004 Post-Demonstration grant under the leadership of Georgia’s Brain and Spinal Cord Injury Trust Fund Commission.

-

Washington State maintains a TBI registry but does not conduct follow up of individuals.

-

New Jersey stakeholders have been working for the past two years with the state’s Center for Health Statistics to develop registries for TBI and spinal cord injury. The registries were brought to life by the Christopher Reeve Foundation and the father of a TBI survivor.

Surveillance. Four of the study states—Alabama, California, Colorado, and New Jersey—have conducted TBI surveillance with funding from the CDC; of these, only Colorado has received CDC funding for the current grant cycle. States use TBI surveillance data, which typically combines death certificate and hospital discharge data, to monitor trends and target prevention efforts. While this information can provide a basis for prevention-related public health monitoring, its utility is limited for services planning. One respondent explained, “ [The TBI surveillance system] captures incidence, or new injuries, which makes sense when the purpose is primary prevention. What service providers really want is point prevalence, that is, how many people live in the state who have had a TBI ever, and currently have a need for services?”

There are a couple of ways to estimate prevalence, this respondent noted: “Some use incidence data as the starting point … However, to use incidence data one needs to know the life expectancy of people with TBI at various ages and gender and the probability of ongoing disability related to the TBI—or some other measure or definition of ‘need for services’ for various age groups and gender …”

Other data collection. Several issues complicate states’ TBI data collection, monitoring, and evaluation efforts. Lack of knowledge about TBI out-

comes and service use and difficulties obtaining funding to sustaining data collection efforts are among respondents’ top concerns. Respondents commented:

“We don’t know a lot about outcomes regarding TBI. Do outcomes vary by ICD-9 code? Who are we designing services for? Different outcomes occur across the severity of TBI.”

“We’re not good at measuring outcomes, mild TBIs, or projecting who will need what types of services. We don’t have good ways to measure information regarding TBI.”

“Funding [for data collection and analysis] from several [federal] sources is drying up … we are constantly looking for grants.”

“We scramble to get money together [for data collection and analysis] from wherever we can. They [federal and state government] keep cutting us.”

“I’m not certain of the role of epidemiology in TBI systems change. Data alone do not create change … individuals make change. Data don’t take into account of values or politics.”

TBI Data Activities in Protection and Advocacy Organizations

The P&As reported variable capabilities for data collection to document and track their TBI activities. Some organizations have licensed a data system developed by their national association; others use in-house tracking systems.

The P&As in the study sample recognized the challenges associated with identifying and tracking their TBI cases, as individuals with TBI approaching the P&As may be advised by phone, or seen in different established programs of their organizations. Anecdotally, all of the seven state P&As stated that individuals with TBI were now more visible as a result of the HRSA P&A grants.

Colorado’s P&A, visited during a study site visit, was able to produce data demonstrating an increase in identified TBI cases addressed at the organization. The Colorado P&A uses an in-house tracking system, but plans to join the more than 40 state P&As that use the Disability Advocacy Database (DAD) operated and maintained by the National Disability Rights Network (NDRN, formerly the National Association of Protection and Advocacy Systems).

Alabama’s P&A currently uses DAD. A P&A respondent explained, “I can ask for information on projects and cases easily. DAD is our whole record-keeping system. It includes information obtained at the phone in-

take, demographics, and the type of inquiry. It also includes the attorney notes.”

National leaders including the Executive Director of the P&A association are working to identify measures for TBI and disability advocacy that can be used by P&As nationwide through DAD.

TBI Program and Systems Evaluation

Few states are conducting evaluation of their TBI programs or efforts to achieve systems change. Several stakeholders called for information on “what works and what doesn’t” and suggested that HRSA establish measures against which they could assess progress achieving systems change. Stakeholders requested technical support for evaluation. Also, interest was expressed in obtaining clinical information about service needs and outcomes throughout the lifecycle of individuals with TBI.

The HRSA TBI Program guidance includes a requirement that grantees evaluate their efforts. All grantees conduct some form of evaluation, but states’ capabilities and resources for evaluation differ widely. States’ evaluation activities range from basic monitoring of project task completion; to conducting process evaluations of conferences, training sessions, and products; to program impact and effectiveness studies. Both state and P&A respondents expressed interest in understanding “what works and what doesn’t” as they develop their programs, but most states have not conducted this type of evaluation. Only one of the sample states, Colorado, included a developed evaluation component that examines the systemic effects of the grant-funded projects.

State respondents expressed frustration at their inability to evaluate and assess their TBI programs, citing lack of staff with skills in data analysis and evaluation, and problems understanding what and how to measure changes. A respondent in a state with mature infrastructure in place stated that, even with available data, their evaluation efforts were lacking. This respondent commented, “Evaluation is the area I’m least satisfied with and feel we need improvement. We need personnel. We have a great data system, but we don’t have anyone to pull it together. I’d love to have a data person, even if just 6 months to a year, to do this.”

New Jersey and Colorado have placed a greater focus on research and evaluation than have other study states. New Jersey established a TBI Research Fund in 2004, spearheaded by the father of a son with a head injury. The Fund is supported by a surcharge on motor vehicle registrations. Colorado directs a portion of its TBI trust fund, initiated by a university-based researcher with interest in TBI, to research, including evaluation. Colorado

has also engaged two evaluators to assess the state’s Implementation grant activities. The evaluators also serve as program consultants, sharing results with the state and its TBI Advisory Board.

A national respondent reported that a subgroup of grantees and the federal program have started meeting to discuss evaluation issues and possible measures. The group is exploring the question, “What do you need to evaluate to tell you what you need to know?” The group expects to identify key system outcomes for the TBI Program.

V. TBI Technical Assistance Center

The TBI Technical Assistance Center (TBI TAC) plays a major role facilitating information sharing among state grantees and, to a lesser extent, P&As. State grantees and P&As provided strong praise for the assistance, support, and information across states available through TBI TAC. All states provided examples of how they were able to avoid “reinventing the wheel” by contacting the TBI TAC or other grantees of the program for brochures, training materials, and general advice. The annual grantee meeting and the list serv received high marks. The P&As also rated TBI TAC highly, but noted they receive information primarily through the national P&A association.

The HRSA TBI Program supports TBI TAC through a contract with the National Association of State Head Injury Administrators (NASHIA). TBI TAC was established to help states in the planning and development of effective programs that improve access to health and other services for individuals with TBI and their families. TBI TAC staff specialists provide states with a range of technical assistance offerings, including: annual grantee meetings, a web-based Collaborative Space to share documents and other information, a grantee list serv, individualized site visits, and others. TBI TAC also develops and disseminates a variety of specialized documents and initiatives for HRSA’s TBI Program. TBI TAC serves all HRSA TBI Program grantees. Brain injury organizations and individuals with interests in TBI services can request access to the TBI TAC web site.

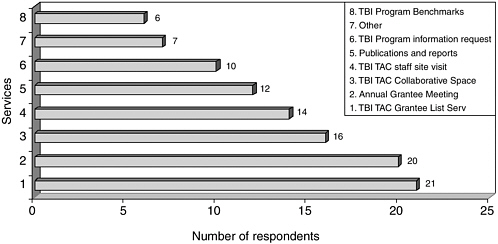

Twenty-five respondents provided information about their use of TBI TAC. Respondents’ use of specific services by type is shown in Figure E-2, below. The most frequently used services include the TBI TAC grantee list serv and the Annual Grantee meeting, named by 21 and 20 respondents, respectively.

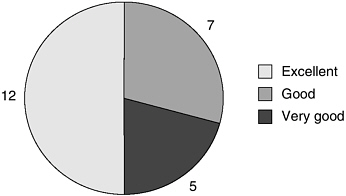

TBI TAC services received above average ratings from these users. Twelve of 24 respondents rated the TBI TAC offerings as “excellent,” five

FIGURE E-2 Respondents’ use of specific services, by type.

respondents rated TBI TAC as “very good,” and seven rated it as “good.” No respondents rated the services as average, fair, or poor. (See Figure E-3.)

Two stakeholders representing national organizations questioned the appropriateness of the amount of funding directed to the TBI TAC in the context of overall HRSA TBI Program funding, and whether or to what extent the TBI TAC should provide non-technical assistance program administrative support to the HRSA TBI Program. State respondents were not always clear about roles and relationships between HRSA and TBI TAC for program administration.

FIGURE E-3 TBI TAC user ratings.

While states praised the services provided by the TBI TAC, one national stakeholder raised concerns about the level of resources provided to the TBI TAC. This respondent noted that the TBI TAC receives a generous portion of HRSA’s TBI Program appropriation2 compared with the limited funding provided to states and the P&As, stating …“It’s the elephant in the living room. Do we really need to be spending this much on the TBI TAC?”

Another respondent raised questions about role clarity and potential conflicts of interest involving the TBI TAC and the HRSA TBI Program, commenting: “The TBI TAC is in a difficult position. They are the TA Center, but also grant staff for HRSA. It is a conflicting role. It creates a situation where people in states can feel they’re being spied on … The same people there to help them are the ones asking for their grantee reports. It’s too much to expect, it leads to a conflict. Some people resent it.”

The HRSA TBI Program Director as well as the TBI TAC Director both recognized and appreciated the dilemma and the necessity of this close relationship—and the importance of drawing a clear line between official government responsibilities that remain with HRSA, and administrative responsibilities that can be delegated to the TBI TAC. The relationship is especially significant given program staffing and resource limitations at HRSA. One respondent suggested that dedicated staff could be housed at NASHIA or another organization outside government, maintaining a separation of the technical assistance and program administration functions of the TBI TAC.

VI. HRSA TBI Program Grantee Experience

The HRSA TBI Program is administered by HRSA’s Bureau of Maternal and Child Health, with program oversight provided by a Public Health Services Commission Corps Program Director. The TBI Program has had four Program Directors since it was established in the Bureau in 1997. The current TBI Program Director does not have staff, and noted the challenges of overseeing several types of state grants and P&A grants, as well as providing contract oversight of the TBI TAC and other administrative activities relating to the TBI Program. The TBI Program Director currently delegates some program support activities to the TBI TAC, but retains program authority and responsibility on behalf of the government.

State and P&A stakeholders were asked to comment on their experiences with the HRSA TBI Program. Respondents were asked to name ben-

efits and drawbacks of their states’ participation. Respondents were also asked to provide comments and suggestions for program improvement. Stakeholders’ responses are summarized below.

Benefits of the HRSA Grant Program

Stakeholders credited the HRSA TBI Program with several types of benefits in their states. State grantees and P&As noted that HRSA funding has increased the visibility of TBI and related issues among state agencies, providers, and the public as a valuable benefit of the HRSA grant funding. These respondents also named TBI-specific funding for inter-organizational activities and funding for TBI-specific projects and materials as benefits.

Both state grantees and P&As reported that HRSA funding, while limited, was valuable to “jump start” TBI-related activities in their states. The ability to focus on TBI and increased visibility of TBI as an issue were mentioned most frequently as benefits, followed by specific activities and materials developed with HRSA funding. Stakeholders in states with TBI trust funds noted that the HRSA Program helped the state prioritize fund expenditures. Respondents commented

“The HRSA grant stimulated the state to look at the whole system. The benefit was having money for an unrecognized population.”

“The biggest thing the grant has done is to bring attention to TBI. The grant helped to identify issues, the Trust Fund paid for services.”

“TBI-specific funding, products. In state government we have a real lot on our plates. This allows us to focus on TBI.”

Drawbacks of the HRSA Grant Program

State grantees were appreciative of the funding obtained through the HRSA Federal TBI Program, and noted that even small amounts of funding could be effectively leveraged to raise visibility and awareness of TBI. However, many reported that 1-year grants, e.g., Post-Demonstration grants at the $100,000 level, provided insufficient time and resources to impact systems change goals. Stakeholders frequently shared their frustrations at the time consuming preparation required for limited funding, and problems sustaining funding. Stakeholders also commented that building relationships and trust at the community level is required for real systems change, and often requires more than a 1-year time-

commitment. Many called out for formula funding, on a regular schedule to allow program continuity.

Study respondents named issues related to the structure of the HRSA grant program—lack of sustainable funding, competitive grant applications, limited and restricted funding—as the top drawbacks to participation in the HRSA TBI Program. Respondents commented,

“What has turned states off are limited competitive one-year grants. They’re not worth the trouble.”

“Sustainability and having to write a new grant every year is difficult and time consuming. Also, it was difficult to come up with new projects for one year at $100,000.”

“Limited funding. The amount of money is small for P&As, not enough for a dedicated staff member. I’d love a TBI specialist who also provides advocacy. That’s one thing that has held us back. But it also means we all have to learn about TBI in the P&A—we can’t say it’s someone else’s responsibility.”

“One of the things that kept limiting us was we couldn’t do anything about services. If there could be a pilot for service delivery it would be great!”

Other HRSA TBI Program Considerations

The HRSA TBI Program has served as a catalyst for a host of TBI-related activities in the study states, including programs and projects funded by HRSA and others funded independently. However, sustaining state infrastructure and project activities in the absence of HRSA or other funding continues to challenge grantees. Many states reported direct and spillover impacts—and many question how they can continue to support these efforts.

Spillover effects. The HRSA grants have demonstrated both direct and spillover impacts, especially when funding is skillfully leveraged. State and P&A respondents were able to point to direct impacts of the HRSA grant funding, including increased visibility and awareness of TBI, as well as spillover impacts that occurred “as a consequence but not as a direct result” of grant funding.

Respondents provided many examples of TBI-related activities and initiatives undertaken in their states that occurred because awareness of TBI was heightened in multiple spheres of state government, the non-profit and private sectors, and the advocacy community. These include program ex-

pansions, trust fund development, and other activities. Some examples include:

-

New Jersey developed the core components of its state TBI program in anticipation of the state’s receiving their first HRSA grant award. New Jersey’s TBI Trust Fund and TBI Research Fund were developed through efforts initiated without HRSA funding, but were reportedly developed as TBI gained new visibility as a result of HRSA-funded grant activities.

-

Colorado’s CIRCLE programs, established to facilitate information sharing about TBI service needs and availability at the community level, were continued through volunteer efforts when HRSA funding was no longer available. State respondents noted that these successful meetings have been embraced by local stakeholders, and have developed a momentum of their own.

Sustaining program components and infrastructure. Respondents named sustainability of program components as a significant challenge to maintaining program infrastructure established under the HRSA TBI Program. Stakeholders in nearly every state named sustainability of TBI programs developed under the HRSA grant program as a great challenge. States with access to trust fund dollars were sometimes able to continue successful programs and trainings. However, states with limited resources may be unable to continue the momentum of program activity beyond the grant period. Additionally, irregular funding cycles and the uncertainty of competitive grant awards create difficulties for staff retention as well as program sustainability in general.

Looking to the Future

Stakeholders commented on program improvements and reforms in several areas, revealing consistent themes across respondents in the seven study states. Respondents gave positive marks to the flexibility of the HRSA TBI Program in allowing grantees to address issues relevant to their state TBI programs. At the same time, respondents called for more structure and information about state program and service effectiveness in improving outcomes for individuals with TBI and their families. One stakeholder stated, “We’d love to see the program go to a more mature level … How to promote the best outcomes …”

Respondents also directed comments to changes in the grant program application process, funding levels, and time frames. The P&As currently receive formula funding for their TBI applications, and states are calling for

the same, including discretionary support and mechanisms to help sustain their TBI programs.

Some example comments include:

“We are glad the TBI program is there, grateful for funding and support. Would like more discussion on focused issues. And more sophisticated, targeted advice.”

“There should be less emphasis on processes, work more on something universally acceptable. Take the best that works and package it. Share these with other states, hospitals. There MUST be common practices that work! Evaluate them and package them.”

“Continue the system as it is, with more centralized control in the Lead Agency. We need more support for statistics, research, to more accurately target dollars … number crunching capabilities … and more money!”

“Being able to integrate state efforts to a basic level would help …”

“Somehow, local work has to be integrated with state policy change. They need to be pulled together. There needs to be articulation of how the state system overlays [and how the trust fund fits in].”

“We need to educate people … Could HRSA develop things about services, needs across the lifespan of people with TBI? Different strategies as the person ages? So people know what comes with TBI …”

“The main thing is time for the grants and the irregularity of funding. It impacts our ability to get and keep staff.”

“When it’s time to do the grant proposals, the HRSA proposals require more narrative than others we typically do. I’d suggest simplified paperwork for the formula funds.”

States’ suggestions to move to a new structure for state grants have already been addressed. In August 2005 HRSA released its new program guidance, which provides support for 3-year “Partnership Implementation” grants. Seen as a step closer to the formula grant approach, which must be legislatively authorized, the Partnership Implementation grants “meet states where they are.” The new grants replace the Planning, Implementation, and Post-Demonstration grants previously available and, while the new grants will be competitively awarded, they are available to all states and territories.