3

Service Needs and Sources of Funding and Supports for People with TBI-Related Disabilities

People with disabilities related to traumatic brain injury (TBI) need coordinated, long-term services if they are to return to productive activity, learn to compensate for their impairments, or achieve an optimal quality of life. When Congress authorized the Health Resources and Services Administration’s (HRSA) Traumatic Brain Injury Program in 1996 (P.L. 104-166, 1996) and reauthorized it in 2000 (P.L. 106-310, 2000), it specifically addressed the need for these longer term services by directing HRSA to encourage states to improve and facilitate coordinated post-acute service delivery for people with TBI and their families.1

As background for the assessment of the HRSA TBI Program’s impact, this chapter provides an overview of the post-acute service needs and sources of funding and other supports for individuals with TBI and their families. The services required by people with TBI-related disabilities are complex and involve numerous areas of technical expertise, both clinical and nonclinical. Case management; continuing availability of medical care; cognitive and physical therapies; family education, counseling, and respite; emotional support; financial assistance; vocational training; housing; and transportation services are essential to achieving a successful outcome (NIH, 1998).

Because there are few coordinated systems of care for persons with TBI-related disabilities, these individuals may not obtain the post-acute

|

1 |

See Chapter 1 for an overview of the HRSA TBI program and its legislative history. |

|

BOX 3-1 Scott suffered a severe TBI at age 17 and continues to have many language, motor, behavioral, and cognitive deficits. Now, at age 33, he still uses a wheelchair and has marked disinhibition that caused him a recent arrest for public lewdness. He needs constant supervision. Despite his problems, Scott received SIB-R testing scoresa that made him ineligible for his state’s Medicaid development disabilities waiver. Scott’s receipt of a social security death benefit from his father made him ineligible for Medicaid due to his total income exceeding a limitation. Scott is ineligible for the TBI Medicaid waiver in his state because he was younger than 22 when he sustained his injury.

|

services they need. At best, their access to services may be circumscribed by nonclinical variables such as health, disability, or accident insurance; family income; health coverage; geography; primary language for communication; and other cultural and socioeconomic factors (NIH, 1998) (Box 3-1). Over time, as persons with TBI-related impairments grow older and their personal circumstances evolve, their eligibility for services may change and they may encounter new obstacles to care.

A lucky few individuals with TBI-related impairments may obtain some needed services in a serendipitous way (Box 3-2).

WHAT SERVICES DO PEOPLE WITH TBI-RELATED DISABILITIES NEED?

As noted in Chapter 2, TBI usually begins as an acute medical problem. If the individual with the injury is covered by health insurance, initial treatment for the injury may be obtained in a hospital, physician’s office, or other acute health care setting. If the injury is severe enough to require prolonged hospitalization, individuals with no insurance or limited insurance are often covered by Medicaid.

If a person with a TBI survives, however, much of the person’s improvement is likely to occur after the acute crisis ends when health benefits may be limited. Some individuals with severe disabilities must have ongoing

|

BOX 3-2 John lacked private insurance or a family to care for his needs, so following his severe TBI, John was placed in a nursing home. He was in his early twenties, trapped in a facility of elderly patients, with little intellectual or social stimulation and no rehabilitation. Fortunately, a creative director of the institution put John to work in a supervised position washing dishes in the kitchen. Slowly over time, John learned more and more skills and began earning money. Eventually he became a member of the nursing home staff with full health benefits and moved into his own apartment. |

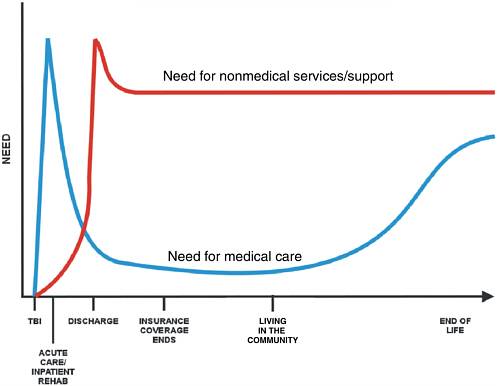

care and supervision in a community-based or residential care setting. Others with TBI-related disabilities may require access to a broad range of nonmedical and medical services and support (NIH, 1998) (Figure 3-1).

FIGURE 3-1 Continuum of needs post-traumatic brain injury.

SOURCE: Langlois, 2005.

In 1998, a National Institutes of Health (NIH) consensus conference on rehabilitation of persons with TBI highlighted an urgent need for research on the optimal mix, duration, and intensity of post-acute services for TBI (NIH, 1998; Chesnut et al., 1999). There is now substantial evidence supporting selected TBI therapies, such as cognitive rehabilitation (Colantonio et al., 2004; Cicerone et al., 2005). However, little is known about the therapeutic factors and patient characteristics that might optimize clinical outcomes (Cappa et al., 2005; Yasuda et al., 2001; Labi et al., 2003; Peloso et al., 2004).2

As discussed in Chapter 2, months, sometimes years, may pass before the full extent of a TBI survivor’s needs becomes evident (Langlois, 2005). This observation holds especially true for children with a TBI, whose deficits may become noticeable and whose handicaps may become increasingly apparent as expectations for social effectiveness and independent behaviors increase during the high school years.

For TBI-related disabilities, insurance coverage of acute and post-acute services may be limited both by what services will be paid for and by what intensity and the duration of services will be paid for (Leith et al., 2004). Coverage of behavioral health services and cognitive and physical rehabilitation is often restricted or not available at all (GAO, 1998; Chan, 2001; Technology Evaluation Center, 2002; Barry et al., 2003; CIGNA, 2005). Focused surveys and qualitative research show that some persons with TBI have persistent unmet needs long after the acute crisis of their injury.

Brown and Vandergoot, for example, studied 430 individuals with TBI and found that they reported significantly more unmet needs than individuals with spinal cord injury (Brown and Vandergoot, 1998).

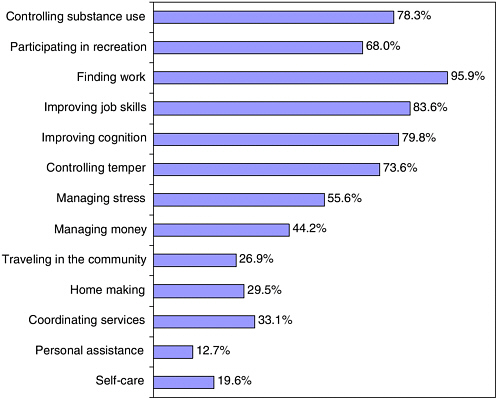

In another study, Corrigan and colleagues conducted a telephone survey of 1,802 persons (or their proxies), aged 15 and older, who were hospitalized for TBI in Colorado in 2000 (Corrigan et al., 2004). One year after being discharged from the hospital, 40.2 percent of the Colorado respondents reported at least one persistent, unmet need for services related to self-care and instrumental activities of daily living, cognitive and emotional functioning, or employment (Figure 3-2). Continuing needs for employment-related, cognitive, and behavioral supports were most prevalent in the Colorado study. The vast majority of respondents with persistent, unmet needs reported requiring help finding work (95.9 percent), job skills (83.6 percent), improving cognition (79.8 per-

|

2 |

The locus for federal research on neurotrauma and rehabilitation care is the Traumatic Brain Injury Model Systems (TBIMS) program in the National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research (NIDRR). TBIMS research activities focus on all aspects of care for persons with TBI. Go to http://www.tbindc.org/registry/center.php for further information. |

FIGURE 3-2 Persistent need for services 1 year post-traumatic brain injury hospitalization.

SOURCE: Corrigan et al., 2004.

cent), controlling substance use (78.3 percent), and controlling temper (73.6 percent). Yet, a substantial proportion of the study group also had ongoing, unmet needs for such basic assistance as self-care (19.6 percent), transportation (26.9 percent), home making (29.5 percent), and help with coordinating services (33.1 percent).

Findings from other surveys of persons with TBI, family members, and providers, as well as reports based on focus groups, regional town meetings, and stakeholder conferences, underscore the prevalence of persistent, unmet needs in the TBI population (Farmer et al., 1996; Corrigan, 2001; Heinemann et al., 2002; Mellick et al., 2003; Leith et al., 2004; Whiteneck et al., 2004; Selassie et al., 2005).

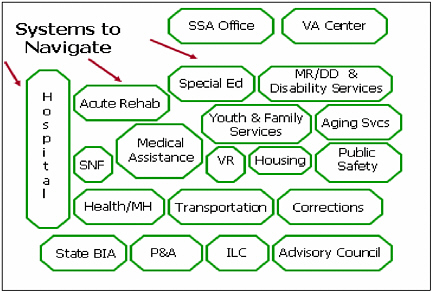

Public and private systems serving persons with TBI are shown in Figure 3-3. For family members and other caregivers, figuring out which

FIGURE 3-3 Public and private systems serving persons with traumatic brain injury.

SOURCE: Connors, 2005.

services are necessary, how to find financial support for needed services, and how to access needed services for a person with TBI may pose a series of daunting logistical, financial, and psychological challenges (Gervasio and Kreutzer, 1997; Leith et al., 2004; Rocchio, 2005; Sample and Langlois, 2005).

A number of surveys suggest that health providers, teachers and other school officials, and police and judicial officers are often poorly informed about the needs of persons with TBI (Corrigan, 2001). Furthermore, every brain injury is different and has unique clinical manifestations requiring a unique array of services for each patient. In an award-winning review of the pathophysiology of TBI, Bigler describes this succinctly (Bigler, 2001):

At the time of injury, every patient brings to that accident a unique set of circumstances and anatomy. The force dynamics of injury will be distinctive to each accident, as will the patient’s anatomy and physiology along with genetic endowment. Each patient’s response to injury also will be unique, particularly in terms of metabolic and vascular reactions. Thus, two patients, of similar age and sex, can be in the same accident (i.e., both seat-belted in the back seat of a vehicle that is hit dead-center, head-on) and come away with very different injuries and sequelae. (p. 101)

Individuals with TBI and their families may ultimately need services from a very broad range of experts which may include primary care and

TABLE 3-1 Types of Services Needed by Persons with TBI and Their Families

|

|

|

SOURCES: GAO, 1998; Heinemann et al., 2002; Corrigan et al., 2004; Sample and Langlois, 2005; Connors, 2005. |

|

specialist physicians, rehabilitation nurses, respiratory care providers, rehabilitation technicians and behavior attendants, neuropsychologists, speech and language pathologists, physical therapists, occupational therapists, therapeutic recreation specialists, school tutors, driving evaluators, dieticians, community reintegration specialists, clinical psychologists, social workers, patient and family service counselors, and insurance experts (Table 3-1). These services are discussed in further detail below.

Case Management

The myriad service systems that provide services that people with TBI-related disabilities and their families need may or may not overlap, may or may not be financed through the same program, and may be available only to certain subgroups of persons with TBI (e.g., children, veterans, or persons residing in certain geographic areas). Case managers can help persons with TBI and their families navigate through the myriad service systems they require. Case management services for persons with TBI and their families may include assessing individual needs, creating service plans, giving referrals to services, helping to obtain financial support for services, coordinating and monitoring service delivery, arranging transportation, identifying alternative living arrangements, and providing assistance on an ongoing basis.

Medical Health Care Services

As noted in Chapter 2, various health problems are common in the wake of a TBI (NINDS, 2002). As a consequence, some individuals with TBI have ongoing or episodic needs for medical management of ongoing problems such as seizures, pain, and psychological issues. They may require ongoing diagnostic testing, treatment, and prescription medications. Neuropsychological evaluation is a critical diagnostic component in identifying the integrity of cognitive functions, such as attention and memory, which impact medical management, rehabilitation, and behavioral therapies. They may also have an ongoing need for various types of durable medical equipment (e.g., wheelchairs and assistive medical equipment).

Cognitive and Physical Rehabilitation Services

Persons with TBI-related disabilities typically need cognitive and physical assessment and rehabilitative services to optimize their ability to process and interpret information, to help ensure their functioning in family and community life, and to enable them to live in the least restrictive setting (NIH, 1998; Ylvisaker et al., 2003, 2005). The objective of the rehabilitation may be “restorative” (that is, to improve specific functions) or “compensatory” (to adapt to a deficit), or both.

TBI rehabilitation services may be provided in a number of different settings, including the home, hospital outpatient units, inpatient rehabilitation centers, comprehensive day programs at rehabilitation centers, supportive living programs, independent living centers, club-house programs, school-based programs for children, and others (NINDS, 2002). Although a person with TBI may initiate rehabilitation services in an inpatient rehabilitation setting, ideally the person will continue rehabilitation services on an outpatient basis for an extended period. As the individual achieves certain therapeutic goals, or as clinical conditions change, some therapies may be discontinued and other therapies may be intensified or added.

Cognitive Rehabilitation Services

Cognitive rehabilitation is a critical component of post-acute TBI care. The objective of cognitive rehabilitation is to improve cognitive functioning and to increase levels of self-management and independence (NIH, 1998). Although the specific tasks are individualized to patients’ needs, cognitive rehabilitation generally emphasizes restoring lost functions, teaching compensatory strategies to circumvent impaired cognitive functions, and improving competence in performing instrumental activities of daily living such as managing medications, using the telephone, and handling finances

(Cicerone et al., 2000, 2005; Miller et al., 2003; Ylvisaker et al., 2003, 2005). The particular focus of the therapy may be on improving specific deficits whether in memory, attention, perception, learning, planning, and/or judgment.

Physical Rehabilitation Services

Physical rehabilitation is also a critical component of post-acute TBI care. People with TBI-related impairments often need an organized program of physical, occupational, speech, and other therapies to regain former abilities or develop new skills to compensate for their impairments. It may also involve modifications to home and work environments.

Behavioral Health Care

People who sustain a TBI are at risk for significant behavioral health problems, including major depression, general anxiety disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, panic disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, antisocial behavior such as criminality and substance abuse, and suicide (Gordon et al., in press; Brown and Levin, 2001; Fann et al., 2004; Oquendo et al., 2004). For persons with TBI who are affected by such problems, access to neurobehavioral and substance abuse counseling and other behavioral remediation services is often fundamental to basic functioning and sound health, to living with family and in the community, and to overall quality of life.

Family and Caregiver Supports

Having access to health information and education, training, social, and psychological services can help TBI caregivers cope and, in turn, potentially improve outcomes for the individual with TBI (Armstrong and Kerns, 2002). As noted earlier, TBI can have intense, long-term social, psychological, and physical health implications for parents, spouses, and other caregivers (Kreutzer et al., 1994; Hall et al., 1994; Ergh et al., 2002; Carnes and Quinn, 2005; Boschen et al., 2005; NASHIA, 2005). Families generally have little knowledge about how to care for individuals with brain injury and are rarely prepared to care for someone with the cognitive deficits and behavioral and emotional changes that may follow a TBI (Lezak, 1986). The related stress is heightened when the TBI leads to dramatic change in the caregiver’s daily routines, employment, housing, financial status, and social life.

|

BOX 3-3 Prior to sustaining a TBI, Peter had a career as a surgical scrub nurse and was known for his people skills. He could keep everyone serene and happy during stressful situations. After 8 weeks of post-TBI rehab, Peter was given a new job as a doctor’s office receptionist at one-fourth the pay. He performed adequately on the computer and on the phone and was often warm and friendly. At times, however, he would snap at complaining patients. When they yelled in protest, he would yell back, inflaming the situation, and he sometimes shouted curses at them. Because of this behavior, he was fired on his 4th day at work as a receptionist. Fortunately, Peter’s wife Rita sought out a rehabilitation program that helped address his disinhibition. Today Peter still earns a modest income, but he has kept his job as an office assistant in a dental office for 7 months, and his wife is no longer contemplating divorce. |

Vocational Rehabilitation Services

Vocational rehabilitation services include a range of services organized to help individuals to cope emotionally, psychologically, and physically with the changing circumstances of their lives (Vandiver et al., 2003; DHHS, 2003). Vocational rehabilitation may involve skills training, job coaching, and supported employment3 to facilitate return to work or, if return to a preinjury job is not an option, alternative employment or other productive activity.

Although there are no definitive estimates of the rate of return to work after brain injury, numerous studies suggest unemployment is high among persons with severe TBI (Wehman et al., 2000; Yasuda et al., 2001; Kreutzer et al., 2003; Wehman et al., 2005). The psychosocial, cognitive, and physical impairments associated with TBI often interfere with an individual’s ability to return to work (Machamer et al., 2005) (Box 3-3). Doctor and colleagues analyzed a group of persons with TBI who had been employed prior to their injury and compared them with the general population’s

|

3 |

Supported employment refers to programs that subsidize paid employment in community settings for persons with severe disabilities who need ongoing support to perform their work. Support can include on-the-job training, ongoing external job coaching, transportation or supervision. Go to http://www.partnersinpolicymaking.com/employment/glossary.html for further information. |

unemployment risk, calculated from transition probabilities; they found that the individuals with TBI were 4.5 times more likely to be unemployed 1 year post-injury than was predicted by the expected relative risk of unemployment in the general population (Doctor et al., 2005).

Legal and Advocacy Services

Legal assistance and advocacy is a critical service for persons with cognitive impairments, psychiatric disorders, or behavioral health problems. Persons with TBI who are cognitively impaired without physical disabilities are particularly likely to be denied needed services—even if they lack the executive skills, such as planning and problem solving, to live independently in the community (GAO, 1998). They are also at risk for ending up homeless or in a nursing home, psychiatric institution, or prison. These people benefit from a legal advocate who can help maximize their potential and their quality of life by finding a suitable place to live, accessing attendant care and/or assistive technology, and obtaining physical, behavioral, and rehabilitation services as needed.

SOURCES OF FUNDING AND SUPPORTS FOR PEOPLE WITH TBI-RELATED DISABILITIES

There is only limited information documenting how well private or public sources of funding cover the post-acute service needs of people with TBI-related disabilities. Eligibility criteria are often confusing and exclusionary (and families may not know what is available). Nonetheless, reviews of eligibility rules for health and disability programs, population surveys on unmet needs (described above), and anecdotal evidence show that there is a substantial discrepancy between needs and availability of funding (GAO, 1998; NIH, 1998; Banja, 1999; Vaughn and King, 2001; Starr, 2001; Drew et al., 2001; GAO, 2005; West, 2000; Technology Evaluation Center, 2002; CIGNA, 2005).

Table 3-2 provides selected details on coverage and eligibility of the principal sources of federal and state funding for TBI services. The Social Security Administration administers two programs of cash benefits: Social Security Income (SSI) and Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI). Eligibility for SSI or SSDI is often the critical path to Medicaid- or Medicare-sponsored health insurance coverage. For low-income persons, eligibility for a Medicaid long-term home and community-based waiver may be the only means to essential services such as personal care, homemaker services, and transportation.

TABLE 3-2 Selected Government Programs Supporting Acute and Post-Acute Service Needs of People with TBI-Related Disabilities

|

Federal Agency and Program |

Covered Services |

Eligibility Criteria |

|

Social Security Administration (SSA) |

||

|

Social Security Income (SSI) |

Cash benefits |

Eligibility is restricted to individuals with resources below the SSI threshold and with a disability that prevents them from working. SSA uses a strict definition of disability that limits adult eligibility to individuals who cannot engage in any “substantial gainful activity” because of a physical or mental impairment that is expected to result in death or to continue for at least 12 months. There are different SSI rules for children. A child with a TBI disability may quality for SSI if he/she has a “medically determinable physical or mental impairment which results in marked and severe functional limitations, and which can be expected to result in death, or which has lasted or can be expected to last for a continuous period of not less than 12 months.” |

|

Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) |

Cash benefits |

For persons under age 65 who are unable to work for a year or more because of a disability. Must be disabled under the SSA definition, and have worked long enough and recently enough. SSDI benefits are based on how much the individual has “paid into the system” by paying income taxes. The required length of employment increases with age group (younger than age 24, 24–31 years old, and age 31 or older). Benefits usually continue until a person is able to work again on a regular basis. Special |

|

Federal Agency and Program |

Covered Services |

Eligibility Criteria |

|

|

“work incentives” provide continued benefits and health care coverage to help with the transition back to work. At age 65, SSDI benefits automatically convert to Social Security retirement benefits. |

|

|

Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) |

||

|

Medicaid |

Joint federal/state program. At the state level, Medicaid functions as a health insurance plan covering a core set of mandatory benefits including inpatient and outpatient hospital care, physician services, and nursing facility care. States have the option to cover rehabilitative services and prescription drugs. Medicaid’s long-term home and community-based waivers give states the option of providing services such as personal care, homemaker services, and non-medical transportation, to adults who are disabled by TBI. The specific services covered by a waiver vary by state. Medicaid also provides supplemental coverage to low-income Medicare beneficiaries for services not covered by Medicare Part A (e.g., outpatient or prescriptions) and Medicare premium, deductibles, and cost sharing. |

TBI-related disability may qualify persons for Medicaid coverage under several criteria related to the disability, income and resource standards, immigration status, and residency in the state where Medicaid benefits are requested. Eligibility for receiving SSI cash benefits (see above) is the primary pathway to Medicaid coverage: in 39 states and the District of Columbia, Medicaid coverage is automatic for persons eligible for SSI. In 11 states, Medicaid eligibility is separate from SSI participation. In some states, individuals with TBI disability may be eligible for Medicaid if they are “medically needy,” i.e., they meet the SSI disability standard and their income, less medical expenses, falls below a state-established threshold. This route to Medicaid coverage is especially relevant to persons who are hospitalized or institutionalized at considerable expense. Eligibility for services under a TBI Medicaid waiver is at each state’s discretion. In 2002, 22 states had a Medicaid waiver program for persons with TBI. Half of these waivers limited eligibility to persons with income up to 300 percent of SSI. Other |

|

|

states capped eligibility at or below 100 percent of SSI. Access to waiver services is often. |

|

|

Medicare |

Part A: Hospital stays, skilled nursing facility care (after a 3-day hospital stay and not custodial care), home health care, hospice care. Prescription medications. Part B: Optional medical insurance for physicians’ services and other outpatient services including physical, occupational and speech therapies; some durable medical equipment and home health care, and clinical laboratory. Optional prescription drug coverage as of January 1, 2006. |

Persons who qualify for SSDI payments are automatically eligible for Medicare after a 24-month waiting period (i.e., because they meet the SSA standard for long-term, serious disability). Disabled adult children of Medicare beneficiaries are also eligible even after the parent’s death. |

|

Department of Education |

||

|

Vocational Rehabilitation (VR) |

Joint federal/state program. States have the option to provide services to adults who are disabled by TBI so that they can reenter the community. Covered services may include rehabilitative therapies and supported employment. Federal support for the program is limited to 18 months. |

Must have a physical or mental impairment that is a substantial impediment to employment; be able to benefit from VR services in terms of employment; and require vocational rehabilitation services to prepare for, enter, engage in, or retain employment. |

|

Independent Living Services (ILS) |

ILS provides training, peer support, advocacy, and referral through a decentralized system of federally funded programs to help people with disabilities live independently. ILS centers are |

Individuals with significant physical, mental cognitive, or sensor impairments whose ability to function independently in the family or community or whose ability to obtain, maintain, or advance in employment is substantially limited. |

|

Federal Agency and Program |

Covered Services |

Eligibility Criteria |

|

|

required to provide four core services: independent living skills training, peer support, advocacy, and referral on a continuing basis. States have the option to purchase additional services, such as personal assistant services or home modifications. |

|

|

State Protection and Advocacy for Assistive Technology |

Advocacy assistance in obtaining funding for a wide range of assistive technology devices, including shower chairs, adapter computer equipment, access ramps and lifts for the home, and custom, power wheelchairs. Also covers training for using the devices. |

Eligibility is granted to any individual with a disability who seeks funding for an assistive device or service. Funding, however, is very limited. States receive federal grants of $50,000 to $100,000 per year to furnish the assistive technology needs of all disabled individuals (including persons with TBI). |

|

SOURCES: GAO, 1998; Sheldon and Ronald, 2001; Drew et al., 2001; Crowley and Elias, 2003; Kitchener et al., 2005; NASHIA, 2005a; Catalog of federal domestic assistance. |

||

SUMMARY

This chapter has described the post-acute service needs and sources of funding and other supports for persons with TBI, providing background for the IOM committee’s assessment of the HRSA TBI Program. Although the research literature has limitations, there is convincing evidence that individuals with TBI have persistent impairments in activities of daily living, ability to return to work, social skills, relationships, and community participation.

Finding needed services is typically a logistical, financial, and psychological challenge for family members and other caregivers. People with TBI require access to diverse services including case management, health care services, cognitive and physical rehabilitative therapies, behavioral health care services, family and caregiver supports, vocational rehabilitation, housing, and transportation services. Eligibility criteria for services and supports are often confusing and exclusionary (and families may not know what is available). Few coordinated systems of care exist so that access to funding is typically driven by nonclinical variables, such as family income, health coverage, geography, and other socioeconomic factors that may change over time.

Given the array of services that may be necessary for a given individual, it is a major problem for that person and family when services are not coordinated. It is easy to get lost, depressed, or desperate. Guidance through multiple potential sources of care through public and private agencies, and system coordination are prima facie essential conditions for adequate service.

REFERENCES

Armstrong K, Kerns KA. 2002. The assessment of parent needs following paediatric traumatic brain injury. Pediatric Rehabilitation. 5(3): 149–160.

Banja J. 1999. Patient advocacy at risk: Ethical, legal and political dimensions of adverse reimbursement practices in brain injury rehabilitation in the US. Brain Injury. 13(10): 745–758.

Barry CL, Gabel JR, Frank RG, et al. 2003. Design of mental health benefits: Still unequal after all these years. Health Affairs. 22(5): 127–137.

Bigler ED. 2001. The lesions in traumatic brain injury: Implications for clinical neuropsychology. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology. 16: 95–131.

Boschen K, Gerber G, Gan C, Brandys C, Gargaro J. 2005. Meeting the support services needs of acquired brain injury family caregivers. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 86(10): e3–e4.

Brown M, Vandergoot D. 1998. Quality of life for individuals with traumatic brain injury: Comparison with others living in the community. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation. 13(4): 1–23.

Brown SA, Levin HS. 2001. Clinical presentation of neurological sequelae of traumatic brain injury. In: Head Trauma: Basic, Preclinical, and Clinical Directions. Miller L, Hayes R, Newcomb J, eds. Canada: Wiley-Liss, Inc. Pp. 349–370.

Cappa SF, Benke T, Clarke S, Rossi B, Stemmer B, van Heugten CM. 2005. EFNS guidelines on cognitive rehabilitation: Report of an EFNS task force. European Journal of Neurology. 12(9): 665–80.

Carnes S, Quinn W. 2005. Family adaptation to brain injury: Coping and psychological distress. Families, Systems, & Health. 23(2): 186–203.

Catalog of federal domestic assistance. 84.132 Centers for Independent Living. [Online] Available: http://www.federalgrantswire.com/centers_for_independent_living.html [accessed 01/09/2006].

Chan L, Doctor J, Temkin N, et al. 2001. Discharge disposition from acute care after traumatic brain injury: The effect of insurance type. Archives of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation. 82(9): 1151–1154.

Chesnut RM, Carney N, Maynard H, Mann NC, Patterson P, Helfand M. 1999. Summary report: Evidence for the effectiveness of rehabilitation for persons with traumatic brain injury. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation. 14(2): 176–188.

Cicerone K, Dahlberg C, Kalmar K, Langenbahm D, Malec J, Bergquist T, Felicetti T, Giacino J, Harley J, Harrington D, Herzog J, Kneipp S, Loatsch L, Morse P. 2000. Evidence-based cognitive rehabilitation: Recommendations for clinical practice. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 81: 1596–1615.

Cicerone K, Dahlberg C, Malec J. 2005. Evidence-based cognitive rehabilitation: Updated review of the literature from 1998 through 2002. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 86: 1681–1692.

CIGNA. 2005. HealthCare Coverage Position No. 0124. Cognitive Rehabilitation. CIGNA Health Corporation. [Online] Available: http://www.cigna.com/health/provider/medical/procedural/coverage_positions/medical/mm_0124_coveragepositioncriteria_cognitive_rehabilitation.pdf [accessed 06/22/2005].

Colantonio A, Ratcliff G, Chase S, Kelsey S, Escobar M, Vernich L. 2004. Long-term outcomes after moderate to severe traumatic brain injury. Disability Rehabilitation. 26(5): 253–261.

Connors S. 2005. Resource Facilitation in Brain Injury. Presentation at the meeting of the Institute of Medicine Workshop on Traumatic Brain Injury. Washington, DC: The National Academies.

Corrigan J. 2001. Conducting statewide needs assessments for persons with traumatic brain injury. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation. 16(1): 1–19.

Corrigan JD, Whiteneck G, Mellick D. 2004. Perceived needs following traumatic brain injury. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation. 19(3): 205.

Crowley JS, Elias R. 2003. Medicaid’s Role for People With Disabilitites. Washington, DC: Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured.

DHHS (Department of Health and Human Services). 2003. Glossary of Disability, Aging and Long-Term Care Terms. [Online] Available: http://aspe.hhs.gov/daltcp/diction.shtml#ADLs [accessed 10/21/2005].

Doctor J, Castro J, Temkin N, Fraser R, Machamer J, Dikmen S. 2005. Workers’ risk of unemployment after traumatic brain injury. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 11: 747–752.

Drew P, Terrill C, Parrett A. 2001. Where to Turn … Disability Programs Under the Social Security Administration. Alexandria, VA: Brain Injury Association.

Ergh T, Rapport L, Coleman R, Hanks R. 2002. Predictors of caregiver and family functioning following traumatic brain injury: Social support moderates caregiver distress. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation. 17(2): 155–174.

Fann JR, Burington MS, Leonetti A, Jaffe K, Katon WJ, Thompson RS. 2004. Psychiatric illness following traumatic brain injury in an adult health maintenance organization. Archives of General Psychiatry. 61: 53–61.

Farmer JE, Clippard DS, Luehr-Wiemann Y, Wright E, Owings S. 1996. Assessing children with traumatic brain injury during rehabilitation: Promoting school and community reentry. Journal of Learning Disabilities. 29(5): 532–548.

GAO (Government Accountability Office). 1998. Traumatic Brain Injury: Programs Supporting Long-Term Services in Selected States. HEHS-98-55. Washington, DC: GAO. [Online] Available: http://www.gao.gov/archive/1998/he98055.pdf.

——. 2005. Federal Disability Assistance: Wide Array of Programs Needs to Be Examined in Light of 21st Century Challenges. GAO-05-626. Washington, DC: GAO.

Gervasio A, Kreutzer J. 1997. Kinship and family members’ psychological distress after brain injury: A large sample study. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation. 12(3): 14–26.

Gordon W, Zafonte R, Cicerone K, Cantor J, Lombard L, Goldsmith R, Chanda T, Brown M. 2006. Traumatic brain injury rehabilitation: State of the science. American Journal of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 85(4):343–382.

Hall K, Karzmark P, Stevens M, Englander J, O’Hare P, Wright J. 1994. Family stressors in traumatic brain injury: A two-year follow-up. Archives of Physical Medicine Rehabilitation. 75: 876–884.

Heinemann A, Sokol K, Gavin M, Bode R. 2002. Measuring unmet needs and service among persons with traumatic brain injury. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 83: 1052–1059.

Kitchener M, Ng T, Grossman B, Harrington C. 2005. Medicaid waiver programs for traumatic brain and spinal cord injury. Journal of Health & Social Policy. 20(3): 51–66.

Kreutzer J, Serio C, Bergquist S. 1994. Family needs after brain injury: A quantitative analysis. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation. 9(3): 104–115.

Kreutzer JS, Marwitz JH, Walker W, Sander A, Sherer M, Bogner J, Fraser R, Bushnik T. 2003. Moderating factors in return to work and job stability after traumatic brain injury. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation. 18(2): 128–138.

Labi ML, Brentjens M, Coad ML, Flynn WJ, Zielezny M. 2003. Development of a longitudinal study of complications and functional outcomes after traumatic brain injury. Brain Injury. 17(4): 265–278.

Langlois JA. 2005. Traumatic Brain Injury: Epidemiology, Issues and Challenges. Presentation at the meeting of the Institute of Medicine Workshop on Traumatic Brain Injury. Washington DC: The National Academies.

Leith KH, Phillips L, Sample PL. 2004. Exploring the service needs and experiences of persons with TBI and their families: The South Carolina experience. Brain Injury. 18(12): 1191.

Lezak M. 1986. Psychological implicatons of traumatic brain damage for the patient’s family. Rehabilitation Psychology. 31(4): 241–250.

Machamer J, Temkin N, Fraser R, Doctor JN, Dikmen S. 2005. Stability of employment after traumatic brain injury. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 11: 807–816.

Mellick D, Gerhart KA, Whiteneck GG. 2003. Understanding outcomes based on the post-acute hospitalization pathways followed by persons with traumatic brain injury. Brain Injury. 17(1): 55.

Miller M, Burnet D, McElligot J. 2003. Congenital and acquired brain injury. 3. Rehabilitation interventions: Cognitive, behavioral, and community reentry. Arch Phys Med Rehabili. 84(Suppl 1): S12–S17.

NASHIA (National Association of State Head Injury Administrators). 2005a. Guide to State Government Brain Injury Policies, Funding and Services. [Online] Available: http://www.nashia.org [accessed 10/04/2005].

——. 2005b. Individual and Family Supports: A Federal TBI Program Issue Brief. Unpublished.

NIH (National Institutes of Health). 1998. NIH Consensus Statement: Rehabilitation of Persons With TBI. Bethesda, MD: NIH. 16. [Online] Available: http://odp.od.nih.gov/consensus/cons/109/109_statement.pdf [accessed 06/13/2005].

NINDS (National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke). 2002. Traumatic Brain Injury: Hope Through Research. Bethesda, MD: NIH. [Online] Available: http://www.ninds.nih.gov/disorders/tbi/detail_tbi.htm [accessed 06/10/2005].

Oquendo MA, Friedman JH, Grunebaum MF, Burke A, Silver JM, Mann JJ. 2004. Suicidal behavior and mild traumatic brain injury in major depression. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 192(6): 430–434.

Peloso PM, Carroll L, Cassidy J, Borg J, von Holst H, Holm L, Yates D. 2004. Critical evaluation of the existing guidelines on mild traumatic brain injury. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine. (supplement 43): 106–112.

P.L. 104-166. Traumatic Brain Injury Act of 1996.

P.L. 106-310. Children’s Health Act of 2000.

Rocchio C. 2005. Long Term Impact on the Family As a Consequence of TBI. Presentation at the meeting of the Institute of Medicine Workshop on Traumatic Brain Injury. Washington, DC: The National Academies.

Sample PL, Langlois JA. 2005. Linking people with traumatic brain injury to services. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation. 20(3): 270–278.

Selassie AW, McCarthy ML, Ferguson PL, Tian J, Langlois JA. 2005. Risk of posthospitalization mortality among persons with traumatic brain injury, South Carolina 1999–2001. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation. 20(3): 257–269.

Sheldon, J, Ronald, R. 2001. Policy and Practice Brief: Fundings of Assistive Technology to Make Work a Reality. [Online] Available: http://digitalcommons.ilr.cornell.edu/edicollect/39/ [accessed 01/11/2006].

Starr J, Terrill CF, King M. 2001. Funding Traumatic Brain Injury Services. Washington DC: National Conference of State Legislators.

Technology Evaluation Center. 2002. Cognitive rehabilitation for traumatic brain injury in adults. Blue Cross and Blue Shield Association. 17(20): 1–25.

Vandiver V, Johnson J, Christogero-Snider C. 2003. Supporting employment for adults with acquired brain injury. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation. 18(5): 457.

Vaughn SL, King A. 2001. A survey of state programs to finance rehabilitation and community services for individuals with brain injury. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation. 16(1): 20–33.

Wehman P, Targett P, Yasuda S, Brown T. 2000. Return to work for individuals with TBI and a history of substance abuse. NeuroRehabilitation. 15: 71–77.

Wehman P, Targett P, West M, Kregel J. 2005. Productive work and employment for persons with traumatic brain injury. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation. 20(2): 115–127.

West M. 2000. The changing landscape of return to work: Implications for supplemental security income and social security disability insurance beneficiaries with TBI. Brain Injury Source .

Whiteneck G, Brooks CA, Mellick D, Harrison-Felix C, Terrill MS, Noble K. 2004. Population-based estimates of outcomes after hospitalization for traumatic brain injury in Colorado. Archives of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation. 85(Supplement 2): 73–81.

Yasuda S, Wehman P, Targett P, Cifu D, West M. 2001. Return to work for persons with traumatic brain injury. American Journal of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation. 80(11): 852–864.

Ylvisaker M, Jacobs H, Feeney T. 2003. Positive supports for people who experience behavioral and cognitive disability after brain injury: A review. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation. 18(1): 7–32.

Ylvisaker M, Adelson D, Braga L. 2005. Rehabilitation and ongoing support after pediatric TBI: Twenty years of progress. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation. 20(1): 95–109.