4

Assessment of the HRSA TBI Program

There are no words to express the fear, anguish, and despair of TBI victims and their families. The problems resulting from severe impairment of a family member are compounded by the frustrations of trying to work within medical, legal, and social systems that for the most part are not equipped to deal with either the immediate or long-term consequences of TBI. Indeed, many patients and their families find that the present system discourages efforts toward self-sufficiency and provides no support for the family as a unit.

—U.S. Interagency Head Injury Task Force Report, 1989

Just 16 years ago, a newly established federal interagency task force reported to the nation that there were serious gaps in post-acute clinical care and rehabilitation for traumatic brain injury (TBI) (NINDS, 1989). The task force concluded that optimal post-acute care was largely unavailable or inaccessible. It also found an urgent need for a federal agency to take lead responsibility for coordinating federal, state, and private sector TBI activities.

Eight years later in the Traumatic Brain Injury Act of 1996, Congress directed the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) to take on a share of the responsibility for advancing state-based TBI service systems. The HRSA TBI Program established in 1997 is a modest federal initiative with broad ambitions; a $9 million grants program aimed at motivating states to create systems improvement on behalf of persons with TBI and their families. The program was designed with the underlying premise—characteristic of other federal infrastructure grant programs—that distributing small grants to states that meet certain requirements will be sufficient to initiate the creation of a sustainable infrastructure and increased capacity for comprehensive, coordinated, and integrated service systems for individuals with TBI.

In Chapter 2 and Chapter 3, the committee concluded that, despite a limited research literature and body of evidence, it is clear that the quality and coordination of post-acute TBI service systems remains inadequate (Box 4-1). This chapter presents the committee’s findings and recommen-

|

BOX 4-1 The quality and coordination of post-acute TBI service systems remains inadequate, although progress has been made in some states. Many people with TBI experience persistent, lifelong disabilities. For these individuals, and their caregivers, finding needed services is, far too often, an overwhelming logistical, financial, and psychological challenge.

|

dations regarding the impact of the HRSA TBI Program. Each set of findings and recommendations is accompanied by a summary of evidence drawn from the committee’s review of the HRSA TBI Program. The committee’s findings and recommendations pertain to three major topics:

-

The impact of HRSA’s TBI State Grants Program on state infrastructure and capacity for improving TBI-related service systems (Box 4-2)

-

The impact of HRSA’s Protection and Advocacy for TBI (PATBI) Grants Program on circumstances for people with TBI-related disabilities

-

The adequacy of the management and oversight of the HRSA TBI Program

|

BOX 4-2 FINDING: The committee finds that the HRSA’s TBI State Grants Program has produced demonstrable, beneficial change in organizational infrastructure and increased the visibility of TBI—essential conditions for improving TBI service systems. There is considerable value in providing small-scale federal funding to motivate state action on behalf of individuals with TBI. Whether state programs can be sustained without HRSA grants remains an open question.

|

|

RECOMMENDATION: The committee recommends that HRSA continue to support and nurture the program.

|

THE IMPACT OF HRSA’S TBI STATE GRANTS PROGRAM1

Effect of the TBI State Grants Program on States’ TBI Infrastructure

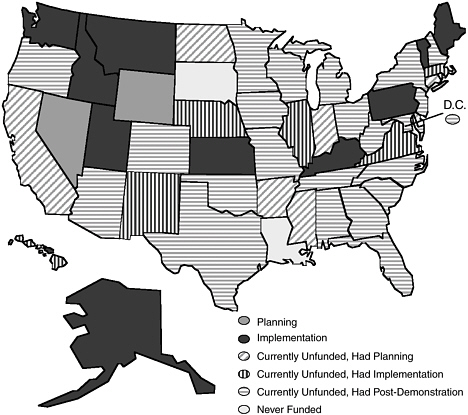

Almost all states have demonstrated interest in expanding their capacity to serve individuals with TBI. All but two states (Louisiana and South Dakota) have applied for and received at least one TBI State Program Grant from HRSA (Figure 4-1). Many states have successfully completed Planning and Implementation Grants. As of 2005, 37 states had received Planning Grants; 40, Implementation Grants; and 23, Post-Demonstration

|

1 |

Unless noted otherwise, this chapter’s findings are drawn from the committee’s commissioned interviews with TBI stakeholders in seven states (Alabama, California, Colorado, Georgia, New Jersey, Ohio, Washington State) (Korda, 2005) and a recent National Association of State Head Injury Administrators/Brain Injury Association (NASHIA/BIAA) survey of TBI stakeholders (Robinson, 2005). Additional information about the committee’s commissioned survey is presented in Appendix B (the interview guide); Appendix D (profiles of TBI initiatives in the seven states); and Appendix E (consultant’s report on the interviews). See Appendix C, Table C-2 for details on the characteristics and self-reported accomplishments of state TBI systems in each state. |

FIGURE 4-1 TBI Program grants by state, 2005.

SOURCE: TBI TAC, 2005.

Grants.2 Twelve states were in the midst of a Planning or Implementation Grant (Table 4-1).

As noted in Chapter 1, HRSA requires all states seeking a federal grant under its TBI State Grants Program to establish or show proof that they have the four mandatory components of a TBI infrastructure—a statewide TBI advisory board, a lead state agency for TBI, a statewide assessment of TBI needs and resources, and a statewide TBI action plan. From 1997 through 2005, many states adopted these basic elements of statewide capacity for creating and coordinating TBI service systems (Table 4-2). As of 2005, 47 states had a lead agency for TBI, 43 states had an approved TBI action plan and an operational TBI advisory board, and 39 states had conducted a TBI needs and resources assessment. Although 12 states3

TABLE 4-1 Number of States Participating in HRSA’s TBI State Grants Program, by Type of Grant, 2005*

achieved these accomplishments on their own, it is likely that most other states would not have progressed to this stage in the absence of the TBI State Program Grants.

The vast majority of states have embraced HRSA’s mandatory TBI infrastructure (Box 4-3), although some have found that incorporating the structure in a way suited to their own political, socioeconomic, and geographic circumstances is challenging. Many states have had to create a wholly new governmental enterprise, requiring the collaboration of numerous state and private agencies.

Lead state agencies for TBI have been designated in at least nine different state agencies, including departments of public health, health, or community health (12 states); human or social services (12 states); rehabilitation services (4 states); education (4 states); and mental health (2 states) (TBI TAC, 2005). There is no evidence to suggest that bureaucratic placement of the lead TBI agency has a significant impact on a state’s capacity for mobilizing effective services. In fact, the labels that states give agencies are not particularly meaningful. The names of state agencies do not reveal their functions and, in many states, the lead TBI agency has multiple roles such as health and social services, social and rehabilitative services, or health and mental hygiene.

In some cases, finding the right administrative home for a lead state agency for TBI has been a process of trial and error. In Georgia, for example, the first two lead agencies for TBI, the State Health Planning Agency

TABLE 4-2 Summary of the Four Core Components of TBI Infrastructure, by State, 2005

|

State |

TBI Advisory Board |

Statewide TBI Action Plan |

TBI Needs & Resources Assessment |

Lead State Agency for TBI |

|

Total all states* |

43 |

43 |

48 |

47 |

|

Alabama** |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

|

Alaska |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

|

Arizona** |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

|

Arkansas |

|

√ |

√ |

√ |

|

California |

|

√ |

√ |

√ |

|

Colorado |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

|

Connecticut |

√ |

|

√ |

√ |

|

Delaware |

|

√ |

√ |

√ |

|

D.C. |

|

√ |

√ |

√ |

|

Florida** |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

|

Georgia |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

|

Hawaii |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

|

Idaho |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

|

Illinois |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

|

Indiana |

|

|

√ |

|

|

Iowa |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

|

Kansas |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

|

Kentucky |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

|

Louisiana |

|

|||

|

Maine |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

|

Maryland |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

|

Massachusetts** |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

|

Michigan |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

|

Minnesota** |

√ |

|

√ |

√ |

|

Mississippi |

|

|

√ |

√ |

|

Missouri** |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

|

Montana |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

|

Nebraska |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

|

Nevada |

√ |

|

√ |

√ |

|

New Hampshire |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

|

New Jersey* |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

|

New Mexico** |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

|

New York** |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

|

North Carolina** |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

|

North Dakota |

√ |

|

√ |

|

|

Ohio** |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

|

Oklahoma |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

|

Oregon |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

|

Pennsylvania |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

|

Rhode Island |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

|

South Carolina |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

|

South Dakota |

|

|||

|

Tennessee** |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

|

BOX 4-3 Successes “We successfully achieved the goals identified in our Planning Grant and for the first time, Virginia had a written ‘plan’ for developing services for people with brain injury. I also believe that the Planning Grant activities and process raised awareness about the needs of people with brain injury in Virginia, but also helped link people with existing services. It also helped to bring together the lead agency, the Brain Injury Association state affiliate, and the state advisory council—we all became focused on moving forward in a more organized, focused manner. This ultimately led to the formation of the Virginia Alliance of Brain Injury Services Providers, which has done an amazing job educating members of the General Assembly and successfully obtaining funding for brain injury services. I would say that the Planning Grant definitely served as a ‘catalyst’ in our state to bring the TBI community together in a more cohesive fashion.” “The HRSA TBI funding has been responsible for brain injury awareness in the state of Colorado. Up until the Planning Grant, there was no relationship with the state or the legislature. Since HRSA’s funding, we have an established Statewide Brain Injury Advisory Board, a designated state agency dedicated to brain injury, a Brain Injury Trust Fund established by the state legislature, energy assistance and Section 8 housing designated specifically for survivors of brain injury, and education for schools through the Brain Stars Program as well as education for rural |

and the Georgia Department of Community Health, had little success in advancing the state’s TBI program; however, Georgia’s current lead agency for TBI, the Brain and Spinal Injury Trust Fund Commission, appears quite promising. In Washington State, the Division of Rehabilitation served as the lead state agency for TBI for the first 2 years of the HRSA grant program, then determined that TBI was not its mission; currently, the Home and Community Services Division of the state’s Aging and Disability Adult Services Administration is at the helm.

Some states have grappled with determining the appropriate size and membership of their statewide TBI advisory board. Colorado, for example, found that too large a group was unwieldy. At first, California’s TBI advisory board was burdened by discord and the challenge of the state’s vast size. Eventually the group worked through its differences and reached consensus on a state action plan. Washington State’s TBI advisory board had difficulty in defining and agreeing on its mission; in order to focus the TBI advisory board, the membership of the board was pared down and planning activities were used to develop a list of goals.

|

areas from the Center for Community Participation. We have the Colorado Information, Resource Coordination, Linkage & Education (CIRCLE) program in the following areas: Denver, Ft. Collins, Greeley, Pueblo, and Grand Junction. All this can be attributed to the HRSA TBI funding. If future funding does not continue, I am afraid that in a decade, we can be back to where we were in 1999. This would be a tragedy.” Frustrations “The need to have a ‘project’ to fund is sometimes less than helpful—if we could fund a staff member on a continuing basis, or if we could add funding to existing state programs to encourage increasing expertise in TBI, it would be far more helpful to us. At some point, too, we need to recognize that we have done all the planning we can do, we have reorganized the system over and over again—we need money for direct services.” “So far, the state has refused to allow the state BIA [Brain Injury Association] affiliate to partner on any aspect of the action plan. The affiliate is represented on the advisory committee, and has offered to take responsibility for key components. All efforts have been met with a negative response.” “Given the lack of services and the defending by the legislature of what did exist on a state level during the grant period I cannot identify any positive outcomes, except for the development of a good plan (albeit unused).” SOURCE: Robinson, 2005; Korda, 2005. |

Of the four required TBI infrastructure components, the tasks of assessing statewide TBI needs and resources and a subsequent TBI action plan have presented the greatest challenge for states. States were often ill equipped to take on the technical task of measuring and documenting TBI needs. Their lead state agencies for TBI conducted or commissioned mail, telephone, and web-based surveys of persons with TBI, families, and providers; held focus groups, town hall meetings, and stakeholder conferences; interviewed providers and state officials; and analyzed secondary data (Corrigan, 2001; Korda, 2005). Their methods, however, were of variable quality. Some state surveys, for example, used nonrepresentative samples and had poor response rates. Analytic data were developed with nonstandard definitions and lacked key clinical variables such as age, time post injury, and severity of injury. Many states also lacked state-specific data, which some researchers regard as essential. Some states’ assessments over-emphasized “need” and gave little attention to documenting available resources (Corrigan, 2001).

Most states now have a statewide TBI action plan in place. The action plans are quite variable. In some states, the action plans are brief, one-page lists of key issues and activities; in other states, the action plans are ambitious, highly detailed documents. Most states’ TBI action plans draw from the state’s TBI needs and resources assessment, along with other information sources.

California developed a comprehensive TBI action plan with the input of many constituents, but according to one observer, “the bottom has dropped out without resources.” Georgia’s TBI action plan identified the need to increase access to transportation; neurobehavioral; and cognitive rehabilitation services; lifelong services; and supports that include rehabilitation and housing.

This experience suggests that states might benefit from more prescriptive, practical guidance from HRSA on their TBI action plans, including scope, structure, and setting of realistic goals to be accomplished within specific timeframes. Such practical guidance from HRSA would be useful both for states and HRSA in evaluating success and failure in achieving state-specified goals. Standard reporting would also allow comparisons to be made more readily across states. Specifications for the statewide TBI plans should be simple and straightforward. The committee notes that the underlying presumptions for this suggestion are a continuing role for HRSA and sustainable funding for TBI at the state level.

Effect of the TBI State Grants Program on States’ TBI Service Systems

Building the capacity for systems improvement has been a principal objective of the HRSA TBI State Grants Program’s Planning Grants

awarded to states. The focus of the program’s Implementation and Post-Demonstration Grants—catalyzing systems improvement—is especially bold. Many states have initiated projects—often in collaboration with community groups—to educate TBI caregivers, the public, schools, prisons and judicial system, physicians, behavioral health care providers; to outreach to underserved persons in schools, institutional settings, and inner-city neighborhoods; to raise awareness among state legislators and other policy makers; and data collection and research (Table 4-3).4

In New Jersey, for example, there was close collaboration between the state TBI program and the state Brain Injury Association to expand outreach and education for faith-based communities and inner-city minority neighborhoods. In Colorado, collaboration between the state TBI program and the Brain Injury Association was also fruitful; together they developed regional community networks, called CIRCLE (Colorado Information, Resource Coordination, Linkage, and Education) Networks, for promoting information dissemination, resource coordination, linkage, and education throughout the state (Colorado Department of Human Services and Brain Injury Association of Colorado, 2005). The networks continue to operate without additional HRSA funding because of dedicated community interest and volunteer support (see Table 4-4, Appendix C, and Appendix D for other examples).

Gauging whether sustainable TBI-related systems improvement has occurred and if it is attributable to HRSA’s TBI State Grants Program is difficult, but it is certain that stakeholders credit the program with motivating states to develop programs and projects that otherwise would have received scant if any attention. Many stakeholders associate favorable systems’ improvements—both direct and indirect—with the TBI State Grants Program. Some observers even question whether states can sustain and capitalize on these improvements without continued federal support (Box 4-4).

Participants in the committee’s commissioned TBI stakeholder interviews in seven states noted that HRSA’s TBI State Grants Program heightened awareness of TBI in multiple spheres of state government, the nonprofit and private sectors, and the advocacy community. They also pointed to “spillover” impacts that occurred as a consequence of the HRSA TBI State Program Grants, including program expansions, trust fund develop-

|

4 |

Appendix C presents a summary of state TBI program characteristics and self-reported accomplishments in all 50 states for 1997–2005. Appendix D presents detailed profiles of TBI initiatives in seven states (Alabama, California, Colorado, Georgia, New Jersey, Ohio, and Washington State). Appendix E presents the original consultant’s report on interviews with TBI stakeholders in the seven states. |

TABLE 4-3 Dedicated TBI Funding by State, 2005

|

State |

Trust Fund |

Medicaid Waiver* |

Special Revenue Funding |

|

Alabama |

√ |

√ |

|

|

Alaska |

|

√ |

|

|

Arizona |

√ |

√ |

|

|

Arkansas |

|

√ |

|

|

California |

√ |

|

|

|

Colorado |

√ |

√* |

|

|

Connecticut |

|

√* |

|

|

Delaware |

√* |

||

|

D.C. |

√ |

||

|

Florida |

√ |

√* |

|

|

Georgia |

√ |

√ |

|

|

Hawaii |

|

√ |

√ |

|

Idaho |

√* |

|

|

|

Illinois |

√* |

||

|

Indiana |

√* |

||

|

Iowa |

√* |

||

|

Kansas |

√* |

||

|

Kentucky |

√ |

√* |

|

|

Louisiana |

√ |

√ |

|

|

Maine |

|

√ |

|

|

Maryland |

√* |

||

|

Massachusetts |

√ |

√* |

√ |

|

Michigan |

|

√ |

|

|

Minnesota |

√ |

√* |

|

|

Mississippi |

√ |

√* |

|

|

Missouri |

√ |

√ |

|

|

Montana |

|

√ |

|

|

Nebraska |

√* |

||

|

Nevada |

√ |

||

|

New Hampshire |

√* |

||

|

New Jersey |

√ |

√* |

|

|

New Mexico |

√ |

√ |

|

|

New York |

|

√* |

|

|

North Carolina |

√ |

||

|

North Dakota |

√* |

||

|

Ohio |

√ |

||

|

Oklahoma |

√ |

√ |

|

|

Oregon |

√ |

|

|

|

Pennsylvania |

√ |

√* |

|

|

Rhode Island |

|

√ |

|

|

South Carolina |

√* |

√ |

|

|

South Dakota |

√ |

|

|

|

Tennessee |

√ |

|

|

|

Texas |

√ |

√ |

|

|

Utah |

|

√* |

|

|

Vermont |

√* |

||

|

Virginia |

√ |

√ |

|

|

State |

Trust Fund |

Medicaid Waiver* |

Special Revenue Funding |

|

Washington |

|

√ |

|

|

West Virginia |

√ |

||

|

Wisconsin |

√* |

||

|

Wyoming |

√* |

||

|

*Indicates that the Medicaid waiver specifically targets persons with TBI. SOURCE: TBI TAC, 2005. |

|||

ment, and other activities. New Jersey, for example, developed the core components of its TBI program in anticipation of the state’s receiving a HRSA TBI State Program Grant. New Jersey’s TBI trust fund and TBI research fund, though also initiated without HRSA TBI State Program Grant funding, were reportedly developed as TBI gained new visibility as a result of New Jersey’s activities related to the HRSA grant.

Several examples of “spillover” effects from the HRSA TBI State Grants Program are apparent in Colorado. According to local observers, TBI’s new visibility contributed to the state legislature’s creating a TBI trust fund and also to increasing participation in the state’s Medicaid TBI waiver program.

The committee observed that a number of mediating factors can influence how HRSA grants influence local TBI systems development. Overall, it appears that no two state TBI service systems have evolved in the same way. Simple serendipity is often an important determinant. A state may have an influential government official or charismatic advocate who champions the TBI cause because of a personal family experience. In Alabama, for example, the crippling assassination attempt on former Governor George Wallace was an early impetus for the state’s widely admired community-based service system that predated but set the context for the state’s HRSA TBI Program. The state’s “homebound” program that serves severely disabled individuals with TBI (or spinal cord injury) was started by Governor Wallace after he experienced problems obtaining basic services (Weiner and Goldenson, 2001).

Success breeds success. It takes time to build effective public and private, state and local systems. Thus, states with already established leadership, interagency cooperation, and/or Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)-sponsored TBI data collection, are better positioned to use the grants more quickly and effectively than other states, which must labor to create “something from nothing.”

TABLE 4-4 Examples of State TBI Program Accomplishments Reported by the Seven Study States, 1997–2005

|

Alabama

|

|

California

|

|

Colorado

|

|

Georgia

|

|

New Jersey

|

|

Ohio

|

|

Washington

|

|

NOTE: See Appendix C, Table C-2 for information on the self-reported accomplishments of state TBI programs, by state. SOURCE: Korda, 2005. |

|

BOX 4-4 Successes “Without the TBI Implementation HRSA grant providing funding to ‘empower’ persons with brain injury through our leadership training, New Mexico would not have had a chance of getting the New Mexico legislature to pass a bill to provide brain injury waiver services. Nor would the governor have been so influenced to sign the bill that became law.” “The HRSA grant stimulated the state to look at the whole system. The benefit was having money for an unrecognized population.” Frustrations “What has turned states off are limited competitive 1-year grants. They’re not worth the trouble.” “As state budgets continue to shrink there are few resources to focus on improving systems (data, developing outcomes, training, setting provider competencies) or expanding capacity. Federal funding needs to be available consistently so states may continue their work and maintain stability.” “The past and current funding level are just enough to whet the appetite, but insufficient for large states to make a significant impact. Equity in funding (per capita formula +) should be considered, plus performance of states and outcomes. Also the variation of needs and complexity of states MUST be taken into consideration, i.e. trust funds or TBI waivers may not be a panacea for every state. Active cooperation among state BIA [Brain Injury Association] and lead agency should be a must for continued funding.” “Sustainability and having to write a new grant every year is difficult and time consuming. Also, it was difficult to come up with new projects for 1 year at $100,000.” SOURCE: Robinson, 2005; Korda, 2005. |

States that cultivate durable sources of TBI funding, such as trust funds, are more likely to sustain the service innovations that are initially developed with HRSA’s grant support (Box 4-5).

In the absence of predictable, long-term funding, it is difficult to maintain the momentum of a grant-funded activity when the funds run out. Holding on to a project staff position, for example, is especially problematic in the context of irregular funding cycles and the uncertainty of competitive grant awards (Box 4-6).

|

BOX 4-5 Eighteen states raise revenues for people with TBI through special trust funds. The revenues are generated by surcharges on traffic violations or fees related to motor vehicle or firearm registrations. The funds are used to pay for direct patient services, outpatient rehabilitation, transitional living services, adaptive equipment and home modifications; family supports such as respite services and psychotherapy groups; research and education; and awareness and prevention initiatives. In some states, trust funds have provided key financing for initiatives first developed through a HRSA TBI State Program Grant. States’ TBI trust fund revenues can be substantial. In 2004, annual trust fund revenues ranged from an estimated $500,000 in Missouri to $15 million in Florida. Alabama’s trust fund, for example, is funded through $100 fines on each “driving under the influence” conviction; the fund generates an estimated $1.2 million annually and, in 2003, subsidized services for more than 1,300 individuals. California’s trust fund receives 0.66 percent of state penalty fund revenues from vehicle code violations; this has been generating approximately $1 million annually. In New Jersey, mentor and training programs first developed with HRSA TBI State Program Grant funding have been sustained by trust fund dollars. Alabama uses trust fund dollars for care coordination for children with TBI, a program that was created with a HRSA TBI State Program Grant. Georgia’s trust fund supports the enhancement of the state’s central TBI registry; it also makes direct payments up to $5,000 annually per recipient to eligible individuals. Some states’ trust funds serve people with spinal cord or other severe injuries, as well as people with TBI. SOURCE: Korda, 2005; NASHIA, 2005. |

Leveraging Medicaid coverage can help facilitate community-based TBI services. In fact, most states have either TBI-specific or generic home and community-based Medicaid waiver programs in place (Table 4-4). Yet in many states, it appears that budgetary concerns limit the number of slots for persons with TBI. Recent evidence suggests that resources might be freed up with increased use of waiver funds. Kitchener and colleagues analyzed national participation and expenditure trends for all TBI/spinal cord waivers during the period from 1995 to 2002. The researchers concluded that average Medicaid expenditures per waiver participant were two-fifths the average cost of institutional care (Kitchener et al., 2005).

HRSA’s New Design for TBI State Program Grants in FY 2006

In August 2005, HRSA announced a new approach to its TBI State Grants Program for FY 2006 (HRSA, 2005). All future TBI State Program

|

BOX 4-6 Successes “This grant funding was absolutely critical in moving Virginia forward regarding the development of a system of care to serve people with TBI. The information developed through the planning grant has been the justification for a number of initiatives, including the state legislature’s approval of over $1 million of annual funding for community-based services. The project has also demonstrated (to many skeptics) the value to unserved areas of the Regional Resource Center concept.” “We are just now, after several years of HRSA funding, starting to see improved services and supports for families with TBI. The HRSA funding has been critical to linking families to necessary services, training service providers, and increasing brain injury awareness of policy makers. Systems change takes time and moving the program to more long-term funding will be beneficial.” Frustrations “Because there was no funding source for continuing the outcomes of the grant no progress has occurred as a result, even though the grant resulted in an excellent plan for the future, with the exception of an 800 information line which the West Virginia Center of Excellence for Disabilities maintains out of their own budget now that the TBI funds are no longer available.” “The programs and infrastructure developed under our state’s HRSA grant were amazingly effective in effecting systems change. However, as funding draws to a close, we are losing one of the ‘change agents’—Regional Resource Coordinator—located throughout the state, as well as the central resource expertise located at Brain Injury of Virginia office … It has also been a challenge to keep the focus on systems change and not move toward service provision which is SO badly needed! It is also difficult to explain to survivors and families why the funds cannot be used to support programs and services.” SOURCE: Robinson, 2005; Korda, 2005. |

Grants will be $100,000 annual Implementation Grants available for project periods up to 3 years; the requirement for states to implement the four core TBI infrastructure components—a statewide TBI advisory board, a lead state agency for TBI, a statewide assessment of TBI needs and resources, and a statewide TBI action plan—remains (Box 4-7). HRSA reports that there are sufficient funds for every state to qualify for a grant.

The committee believes that this change is a step in the right direction. Every grantee operates under unique political, socioeconomic, and geographic circumstances. Every state has a different historical context for

|

BOX 4-7

|

addressing TBI issues. Moreover, most states are beyond the initial stages of infrastructure building and planning. By essentially meeting grantees “where they are,” the 2006 Implementation Grants will allow states to leverage HRSA funds for their specific situations.

THE IMPACT OF HRSA’S PROTECTION AND ADVOCACY FOR TBI (PATBI) GRANTS PROGRAM

Protection and advocacy (P&A) systems for people with disabilities in the states, territories, and the District of Columbia were initially required by Congress as a condition of receiving federal P&A funds under the Developmental Disabilities Assistance and Bill of Rights Act of 1975 (P.L. 103-230, 1975). Thus, when Congress reauthorized HRSA’s TBI Program in the Children’s Health Act of 2000 and directed HRSA to implement the PATBI

SOURCE: HRSA, 2005. |

Grants Program, there already existed an infrastructure of P&A systems to receive the new grants. Moreover, people with TBI-related disabilities, along with many other disabled persons, had long been eligible for P&A services before the PATBI Grants were distributed by HRSA.

It is difficult to discern whether any recent improvements in states’ TBI systems and services can be attributed directly to HRSA’s PATBI Grants Program (Box 4-8). Many TBI stakeholders in the seven states who were interviewed for this study agreed that the PATBI Grants have led their P&A systems to focus on TBI significantly for the first time. Unfortunately, comprehensive and objective data on the TBI-related activities of P&A systems in the states are not available.

The committee’s commissioned interviews with PATBI grantees in seven states (Alabama, California, Colorado, Georgia, New Jersey, Ohio, and Washington State) revealed that P&A systems in the states are variable;

|

BOX 4-8 FINDING: The committee finds that it is too soon to know whether HRSA’s 3-year-old PATBI Grants Program has meaningfully improved circumstances for people with TBI-related disabilities. Nevertheless, PATBI Grants have led to new and much-needed attention to the protection and advocacy (P&A) concerns of people with TBI-related disabilities and their families.

RECOMMENDATION: The committee recommends that HRSA continue to fund the PATBI Grants Program.

|

there is a wide range in their resources and service capacity. Most often, the PATBI Grants have been used in the states to provide information and referrals, to advocate for the special education needs of children with TBI, and to identify persons with TBI who may be inappropriately placed in nursing homes, mental health facilities, prisons, or other residential settings (Table 4-5).5

|

5 |

Additional information about the committee’s commissioned survey of TBI stakeholders in the seven study states is presented in Appendix B (the interview used in the survey); Appendix D (profiles of TBI initiatives in the seven states); and Appendix E (consultant’s report on TBI stakeholder interviews in the seven states). See Appendix C, Table C-3 for details on TBI-related goals and self-reported accomplishments of P&A systems in each of the 50 states. |

TABLE 4-5 PATBI Grant Activities Reported by the Seven Study States, 2005

|

Alabama

|

|

California

|

|

Colorado

|

|

Georgia

|

|

New Jersey

|

|

Ohio

|

|

Washington

|

|

SOURCE: Korda, 2005. |

Many TBI stakeholders interviewed in the seven study states reported that the PATBI Grants have had the greatest impact in the areas of self-advocacy, consumer education, and training of parents and other caregivers (Box 4-9). They also agreed that most P&A systems collaborate closely with their corresponding state TBI program. In one state, P&A advocacy on behalf of children led to new legislation mandating expanded TBI screening of school children.

Nevertheless, a common perception among TBI stakeholders in the seven study states is that the PATBI Grants have not ameliorated the circumstances of persons with TBI, particularly with respect to improving access to community-based services, vocational training, housing, long-term supports, or protection in the judicial and correctional systems. That this perception exists is not surprising given that HRSA’s PATBI Grants are quite modest, and the 3-year-old PATBI Grants Program has not had enough time to tackle such thorny and entrenched social problems.

ADEQUACY OF THE MANAGEMENT AND OVERSIGHT OF THE HRSA TBI PROGRAM

Administration of the HRSA TBI Program

The HRSA TBI Program has been administered by a less-than-skeletal staff—just one full-time individual—since its creation. The program has been shuttled from one division in HRSA’s Maternal and Child Health Bureau to another—including the Division of Child, Family, and Adolescent Health, Special Projects of Regional and National Significance, and most recently, the Division of Services for Children with Special Health Care Needs (Martin-Heppel, 2005). It also has been threatened with debilitating cutbacks, most recently in January 2006 (DHHS, 2006).

Although the committee agrees that in the face of these significant challenges, the HRSA TBI Program contributed to improvements in state-

|

BOX 4-9 Successes “HRSA TBI funding has allowed the P&A to increase and focus more individuals and policy advocacy work on TBI issues and has played a CRITICAL role in supporting consumer/family involvement in public policy development.” “As a result of the grant, the agency was able to significantly increase the number of outreach and educational activities provided. The number of referrals and cases has increased as a result of the activity. Since the outreaches include information on all P&A activities, the number of inquiries, referrals, and cases has increased with the awareness of the agency’s existence.” Frustrations “Due to the very small size of the [HRSA PATBI] Grant, it has done little to increase our capacity to actually provide effective advocacy services except for a small handful of individuals, and in a sense, has possibly done harm by raising expectations in the community that we are not in a position to meet. The budget is inadequate for the P&A to even think about major litigation.” “Funding currently enables us to do some but not all of the work that is required on behalf of the TBI population of California. Our P&A is the only California entity that is working to protect and advance the rights of individuals with TBI in our state and therefore greater support in the future for our efforts is warranted if improvements in access to services and enforcement of the civil rights of individuals with TBI are to be realized.” “The amount of money is small for P&As, not enough for a dedicated staff member. I’d love a TBI specialist who also provides advocacy. That’s one thing that has held us back. But it also means we all have to learn about TBI in the P&A—we can’t say it is someone else’s responsibility.” SOURCE: Robinson, 2005; Korda, 2005. |

level TBI infrastructure and public awareness of TBI, it finds that HRSA’s management and oversight of the program has been inadequate (Box 4-10). To date, perhaps because of insufficient resources, HRSA has not built a management infrastructure to allow for systematic review of either the HRSA TBI Program’s strengths and weaknesses or the state grantee evaluations and final reports that HRSA requires. There is no evidence that HRSA has ever enforced its mandate that TBI grantees in the states conduct program evaluations. However, the TBI Technical Assistance Center (TAC) has developed a self-assessment tool and benchmarks to help states gauge

|

BOX 4-10 FINDING: The committee finds that the management of the TBI Program is inadequate to assure public accountability at the federal level and to provide strong leadership to help states continue their progress toward improving systems for persons with TBI and their families.

RECOMMENDATION: The committee recommends that HRSA lead by example—that it instill rigor in the management of the HRSA TBI Program and build an appropriate infrastructure to ensure program evaluation and accountability. Thus, the committee recommends that HRSA do the following:

|

their progress vis a vis infrastructure development—these provide a useful starting point for program monitoring.6

HRSA should plan and implement—for both grantees and itself—a standardized reporting system to ensure basic accountability and program evaluation. The committee recognizes that doing this may require additional funds and a modest expansion in the HRSA TBI Program’s administrative capacity.

The committee urges the HRSA TBI Program to exercise strong leadership on behalf of the state grantees. Indeed, the program should embody many of the characteristics it demands of the grantees. It should serve as a national information resource on the special needs of individuals with TBI, keep track of emerging issues in state TBI programs, and disseminate information on best practices. It should also advocate for the TBI grantees, by, for example, pressing sister federal agencies to furnish needed data and to address TBI in eligibility rules for other federal programs.

Just as the state TBI programs do, the HRSA TBI Program needs the guidance of an actively engaged advisory board to help garner resources and to develop a vision and action plan for the future. There should be a formal process for appointing the advisory body, and the appointees should represent the relevant federal agencies, state and national brain injury associations, professional groups, TBI protection and advocacy systems, persons with TBI, and family members or other caregivers.

The HRSA TBI Program’s collaboration with other federal agencies involved in TBI-related activities is paramount. The 1988 Interagency Head Injury Task Force has apparently been defunct for years. Although there is some evidence of interagency activity regarding TBI, such as the Federal Interagency Conference on Traumatic Brain Injury, it appears to be ad hoc and irregular. It is not enough to stimulate true collaboration that builds on the unique strengths and resources of the various federal agencies.

The committee urges HRSA to issue and lead a formal call for active, interagency action including at a minimum the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research, National Center for Medical Rehabilitation Research, Defense and Veterans Brain Injury Center, and Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. The Interagency Committee on Disability Research may be a model worth emulating.7

|

6 |

The TBI TAC benchmarks are available at http://www.nashia.org/grantee/tote/TBI%20Program%20Benchmarks.pdf. The self-assessment tool is at http://www.nashia.org/grantee/tote/Self%20Assessment%20Tool%20-%20State%20TBI%20Program.pdf. |

|

7 |

For information on the Interagency Committee for Disability Research, go to http://www.icdr.us. |

TBI Technical Assistance Center (TBI TAC)

Many of the HRSA TBI Program’s administrative duties are the responsibility of its Technical Assistance Center, called TBI TAC.8 TBI TAC is in essence HRSA’s de facto TBI program staff. Since 2002, TBI TAC has been operated under a contract between HRSA and the National Association of State Head Injury Administrators (NASHIA).9 TBI TAC’s activities include the following:

-

Providing general technical assistance to HRSA TBI Program grantees.

-

Maintaining an e-mail listserv that allows HRSA TBI Program grantees and other participants to post inquiries, disseminate funding announcements, share best practices, and other program materials. In 2005, listserv messages covered a wide range of topics including Medicaid TBI waiver design, nursing home transitions, return to work, grants watch and other funding ideas, program assessment tools, training and education, services for special populations (e.g., young adults, students), domestic violence, policy development, and protection and advocacy.

-

Providing TBI program benchmarks for states to assess their progress in establishing the core components of a TBI infrastructure; state participation is optional (TBI TAC, 2005).

-

Maintaining the TBI Collaboration Space or TBICS (http://www.tbitac.nashia.org/tbics/), an online database for grantees and others affiliated with the HRSA TBI Program. The regularly updated database includes recent and archived documents related to action plans, advisory boards, lead agencies, needs and resources assessment methods, program evaluation, funding strategies for sustainability (e.g., trust funds, Medicaid waivers), data issues, product and policy development, public education and training, collaboration and coalition building, and service coordination.

-

Sponsoring national meetings and webcasts related to TBI.

TBI TAC is highly regarded by state grantees and other stakeholders. It has clearly become an essential resource and information forum. Contracting out technical assistance to NASHIA has the advantage of utilizing cross-state experience and knowledge about TBI by an organization representing individuals working in the field at the state level. Currently, however, the lines of responsibility between the HRSA program office and TBI TAC are blurred; many individuals interviewed for this study remarked that they were confused about the respective roles of HRSA and TBI TAC. Further-

|

8 |

See Chapter 1 for additional information on TBI TAC. |

|

9 |

The Children’s National Medical Center (Washington, D.C.) held the TBI TAC contract from 1997 to 2002. |

more, the committee questions the extent to which the TBI TAC assumes delegated administrative and oversight functions for the federal government. As an entity of NASHIA, the national membership association for state TBI program officials and other individuals concerned with state and federal brain injury policy, it represents the very agencies that seek HRSA funding.

The committee urges HRSA to evaluate the TBI TAC in order to learn how it might best serve the TBI program and its grantees. HRSA should also carefully assess which of its TBI Program activities are optimally performed by TBI TAC (versus the HRSA program office).

SUMMARY

In the years since the HRSA TBI Program’s implementation in 1997, there has been demonstrable improvement in two essential preconditions for improving TBI service systems—state-level TBI systems infrastructure and the overall visibility of TBI have grown considerably. The committee is impressed with what has been done and rates the HRSA TBI Program overall a success. There is considerable value in providing small-scale federal funding to catalyze state action. Nevertheless, substantial work remains to be done at both national and state levels.

So far, the HRSA experience shows that no two state TBI programs have evolved in the same way. Not surprisingly, states with established leadership, interagency cooperation, and/or a CDC-sponsored TBI data collection, have been better positioned to use the TBI grants more quickly and effectively than other states. Yet serendipity also plays a part; there is no substitute for having an influential policy maker who champions the TBI cause.

The committee also believes that management and oversight of the HRSA TBI Program has been inadequate. HRSA has shown only token attention to evaluation of the state grantees or the HRSA TBI Program itself. The states are ill equipped to conduct technical evaluations and require constructive guidance in this area.

Since its implementation, the HRSA TBI State Grants Program has been handled as a grant program designed to establish four core TBI organizational and strategic components in each state but to allow considerable state variation. This approach was realistic in two ways: (1) by recognizing the different bases on which improvement might take place in different states (some already organized for TBI, others not); and (2) by encouraging entrepreneurship and innovation. TBI TAC has provided valuable assistance as an information base and a spur for diffusion of innovation across the states.

The committee concludes that it is too soon to know whether HRSA’s 3-year-old PATBI Grants Program has meaningfully improved circum-

stances for persons with TBI. It appears that P&A systems for people with disabilities in the states have begun to focus on TBI significantly for the first time. To evaluate the impact of the PATBI Grants, HRSA should collect data on P&A systems TBI-related activities. In addition, HRSA should ensure that people with TBI-related disabilities and their families are aware of P&A services in their communities.

Further progress in the development of TBI systems and services in the states will be elusive if HRSA does not address the program’s fundamental need for greater leadership, data systems, additional resources, and improved coordination among federal agencies. It is worrisome that the modestly budgeted HRSA TBI Program has been vulnerable to budget cuts. The states are now at a critical stage and will need continue federal support if they are to build an effective, durable service system for meeting the needs of individuals with TBI and their families. The state TBI programs will find it difficult to maintain the momentum of HRSA grant-funded TBI activities when the HRSA funds run out. The HRSA TBI Program should be a priority for HRSA.

REFERENCES

Colorado Department of Human Services and Brain Injury Association of Colorado. 2005. CIRCLE NETWORK: Colorado Information, Resource Coordination, Linkage, & Education. Denver, CO.

Corrigan J. 2001. Conducting statewide needs assessments for persons with traumatic brain injury. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation. 16(1): 1–19.

DHHS (Department of Health and Human Services). 2006. Budget in Brief Fiscal Year 2006. [Online] Available: http://www.hhs.gov/budget/06budget/FY2006BudgetinBrief.pdf [accessed 2/6/2006].

HRSA (Health Resources and Services Administration). 2005. Program Guidance FY 2006 State Implementation Grants (HRSA-06-083).

Kitchener M, Ng T, Grossman B, Harrington C. 2005. Medicaid waiver programs for traumatic brain and spinal cord injury. Journal of Health & Social Policy. 20(3): 51–66.

Korda H. 2005. Stakeholders Assess the HRSA TBI Program: National and State Interviews. Paper Prepared for the IOM Committee on Traumatic Brain Injury.

Martin-Heppel J (JMartin-Heppel@hrsa.gov). Budget data. E-mail to Jill Eden (jeden@nas.edu). November 30, 2005.

NASHIA (National Association of State Head Injury Administrators). 2005. Guide to State Government Brain Injury Policies, Funding and Services. [Online] Available: http://www.nashia.org [accessed 10/04/2005].

NINDS (National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke). 1989. Interagency Head Injury Task Force Report. Bethesda, MD: DHHS.

Pub. L. No. 103-230. Developmental Disabilities Assistance and Bill of Rights Act of 1975. 1975.

Robinson L. 2005. Impact of HRSA State Program Grants and HRSA Protection and Advocacy Grants. McLean, VA: BIAA and NASHIA.

TBITAC (Traumatic Brain Injury Technical Assistance Center). 2005. Pathway for Systems Change: Benchmarks. Bethesda, MD: TBI TAC.

Weiner J, Goldenson S. 2001. Home and Community-Based Services for Older People and Younger Persons With Physical Disabilities in Alabama. Washington, DC: Urban Institute.