1

Introduction

SUPPLY CHAINS IN PRIMITIVE ECONOMIES are highly compressed in time and space: hunting and gathering is mostly done day-of-the-meal and not-too-far-from-home. However, economically developed countries derive their enormous productivity advantages from high levels of specialization of work and from long extensions of supply chains in time and space.

The extensions in space can be seen everywhere. Supply chains in modern economies often begin where ores are mined and oil is pumped from wells. Those raw materials are passed to metal manufacturers, who ship their metal products to fabricators of parts, who in turn pass the parts to assemblers. Next in the supply chain come the wholesale and retail distributors, who ultimately deliver the finished products to consumers’ homes. People in the United States might be wearing shirts made from cotton grown in Egypt, spun into thread in North Carolina, woven into fabric in Italy, and sewn into garments in Costa Rica using sewing machines made in China.

The extension of supply chains across time is also easily found. Consider, for instance, how the products and services delivered to homes all over the world today still come to some significant extent from the creative labor of Thomas Edison on the electric motor in Menlo Park, New Jersey, in the 1870s and from the creative labor of Gottliev Daimler and Karl Benz in Germany on the internal combustion engine in the 1880s.

The evolution of supply chains in both time and space can improve the overall efficiency of an economy and is an indispensable part of eco-

nomic progress, even though it may threaten the livelihood of those who are skilled at the old ways of doing things. If the changes in the supply chains are gradual, the disruptions may be so small and the progress so great that everyone benefits. But when technological advances allow a more rapid extension in time and space of the different stages of making, distributing, and selling or purchasing a good or service, there can be substantial losses for the workers and physical assets that are committed to the old ways. The economic and societal effects of these kinds of changes can lead to pressure for mitigating interventions by government. This is nothing new. In the early 1800s the British textile industry complained bitterly about the negative impact of competition from cheap imports from U.S. suppliers. The British government, in response, prohibited the export of the Cartwright power loom, the latest and most efficient equipment at the time for weaving cloth. But in 1810, Francis Cabot Lowell, during a visit to Manchester, England, viewed the Cartwright power loom in operation and brought the design back to America in his head (Rothenberg, 2000).

ADDRESSING THE CHARGE

Overall, looking at recent trends in wages, the trade deficit, and other economic indicators, as well as the predictions and insights provided by economic theory, there are many different perceptions of offshoring, and these often get linked by association to wider trends in the economy. It is essential to understand better the process of offshoring—its nature, direction and magnitude—and to which of the wider trends in the economy it is linked.

The primary task of the committee’s study is the need for an analysis of domestic content of the goods and services crossing the U.S. border—that is, the accounting for imports and exports when there are complicated multicountry supply chains. The committee held extensive discussions on both the narrow question of measuring content and the broader context of offshoring.

In this regard the committee was invited to ask whether answering the content question is actually useful to understanding the broader economic and workforce trends in the U.S. economy. Does answering the content question provide any useful information on offshoring that can help guide policy responses? How much should policy makers be concerned about the content question or proxy measures?

RECENT TRENDS

The exchange of goods across long distances has existed for millennia and predates even the formation of modern nation states. So while international trade itself is not new, what does appear new is the breadth of functions that are being bought from offshore suppliers, including some services for the first time. Like other changes in supply chains, this finer international division of labor has beneficial effects on global efficiency, but it may have important implications for U.S. productivity, U.S. competitiveness, U.S. wages, and U.S. employment.

Although neither international trade in final goods nor trade in raw materials and parts is new, the volume and range of functions that are being transferred across borders is new. Those functions include both mundane services like call centers and less mundane work like software coding.1 The new trend is especially troubling because the intellectual services sector has been the hard rock of U.S. comparative advantage in the world economy and has increasingly been the source of U.S. growth. Moreover, while the new offshoring of intellectual services is occurring the old offshoring of manufacturing work continues unabated.

Data on the flow of exports and imports across borders are routinely gathered by the U.S. government because the country’s economic relationships with other countries affect the U.S. economy and because the U.S. government intervenes in cross-border commerce with tariffs, quotas, and other measures. Some of these data on import and export flows can be used to help answer the “content question” posed for this study, as shown later in this report.

An example helps to clarify some of the issues involved. Consider the production of an engine for a U.S. automobile for export to Canada. It is more than likely that many of the components of the car’s engine will be imported to the United States for incorporation into the engine. These imported goods are likely to be combined with domestically made parts to

assemble the various elements of the car engine. In addition, the automobile company may decide to outsource the assembly of the complete engine to a factory in Mexico. Therefore, the company exports the engine parts, which have in them both domestic and foreign value, to Mexico, where they are assembled into the complete engine that in turn is imported into the United States for assembly into the car. The car is then exported to Canada. The splitting of the production of the car into separate processes carried out in different locations is called fragmentation. This kind of production process leads to the question: With value originating from so many different countries, what part of the car that is exported to Canada is American? Indeed, what part of the engine imported into the United States during the car’s production is American? Aggregating these questions across the economy, the question becomes: What is the U.S. content of the country’s imports and the foreign content of its exports? What does “Made in the U.S.A.” mean in the 21st century global economy?

GETTING THE VOCABULARY RIGHT

An important first step in tackling the issues in this study was to settle on a well-defined vocabulary: words that clearly distinguish transactions that occur across the boundaries of a country from transactions that occur only across the boundaries of a firm are required. Figure 1-1 illustrates the boundary of three firms and the boundary between the two countries in which they are located. One firm operates in both countries. The business transactions from the upper part of the chart to the lower part of the chart are transactions separated by the political boundaries of the country. In the upper left corner of the figure, the internal arrow shows transactions that occur within the boundaries of both the firm and the country. These are called vertically integrated local operations.

Firm A can also engage in transactions that occur within the firm but across country boundaries. These are the intrafirm global procurement operations of a multinational enterprise and are illustrated by the vertical arrow on the left side of the figure. Firm A can also procure goods and services from an unrelated company, Firm B, located in the same country. The arrow between the upper-left corner and the upper-right corner shows these business-to-business transactions—occurring, for example, when one firm hires another firm to do its accounting or custodial work, or when a firm purchases parts from a local independent manufacturer. This is local procurement of goods and services.

FIGURE 1-1 An illustration of outsourcing and offshoring. See text for discussion.

The fourth option is for a Firm A to procure goods and services from an offshore unrelated firm, Firm C. This transaction also falls into the global procurement categorization and is represented by the arrow from the upper-left corner to the lower-right corner in Figure 1-1.

How do the terms offshoring and outsourcing fit into this example? Outsourcing refers to the arrow from Firm A to Firm B, which is vertical disintegration, technically, and does not make reference to political or international boundaries. In contrast, the arrows pointing from the upper part of Figure 1-1 to the lower part represent transactions that do cross political boundaries, which is offshoring. This term encompasses both the global intrafirm operations of a company as well as interfirm operations, as long as the transactions involve the movement of goods and services across international borders. Although “outsourcing” is commonly used to describe the increasing global procurement of goods and services, the committee uses “offshoring,” which covers the activity of concern in our charge.

THE WIDER CONTEXT

The charge to this committee places the content question in the context of “the importance of current trends to [offshoring] and their input on the U.S. economy.” A detailed examination of this very broad context within which the content question is placed, while fascinating in many respects, is beyond the committee’s charge. Nevertheless there are some issues that should be noted.

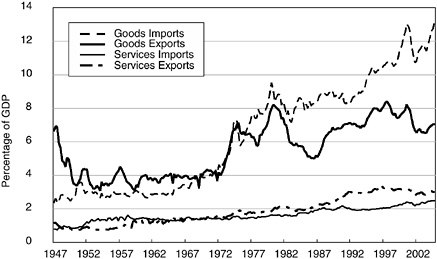

Over the past 40 years, U.S. trade in goods and services has increased significantly, as measured in terms of a share of the gross domestic product (GDP); see Figure 1-2. In the second half of the 20th century, total U.S. trade flows—imports plus exports—rose from 9 percent of GDP in 1960 to 25 percent in 2004. However, since the 1990s there has been a significant decline in terms of international exposure, particularly on the export side.

The increase in the U.S. dependence on international trade and the concomitant loss in U.S. manufacturing jobs is treated by some analysts not as a mere coincidence, but as evidence that U.S. jobs have been lost due to offshoring (Scott, 1999; Bivens, 2004; Scott, 2005); other analysts attribute most of the job loss in manufacturing to technological change (e.g., Baily, 2004). In truth, both technology and trade have effects on wages and employment in the United States.

FIGURE 1-2 U.S. exports and imports of goods and services as a percentage of GDP.

SOURCE: Based on data from the U.S. Department of Commerce.

Wage inequality and skill differentials have increased sharply in the United States in recent years.2 Much research has documented that wage dispersion has increased both between skill groups and within detailed demographic and skill groups. Thus, the wages of individuals of the same age, education, and sex are more unequal today than they were 25 years ago. Recent increases in earnings volatility for U.S. workers and changes in the U.S. jobs market are attributed by some to the effects of offshoring, while others note that the pattern of volatility is widespread and appears to predate offshoring in many sectors, suggesting that other factors may also play a key role.

The loss of jobs to low-wage economies is the most often cited effect of offshoring. The increased ability of U.S. employers to offshore parts of the production process to lower cost suppliers in other countries can have complex and unpredictable effects on the U.S. economy and labor market. Routine work—such as factory floor tasks—is the most easily outsourced and offshored. Because of the cost reductions, firms may move the routine tasks to low-cost foreign locations, and, thereby, lower the demand for U.S. employees doing such work. This kind of work often is done by workers in the middle parts of the U.S. wage structure and education distribution, that is, high school graduates and some college graduates. By contrast, workers with similar levels of skill but in activities involving face-to-face services or performing nonroutine manual tasks—such as, truck drivers, carpenters—are less directly affected by offshoring (Autor, Levy, and Murnane, 2003).

DATA CURRENTLY COLLECTED

The empirical research on offshoring and its wider context is based on a series of data sets, many gathered on a routine basis by the federal government, including international trade flows, foreign investment, and domestic economic indicators. The U.S. Government Accountability Office (Government Accountability Office, 2004) has reported that U.S. government data provide limited insight into the extent of services offshoring by the private sector, but they do not provide a complete picture of the business transactions that the term offshoring can encompass.

Measuring Cross-Border Transactions

Measuring the content of imports and exports requires data on cross-border trade. Such data are compiled on a monthly basis by the U.S. Census Bureau from the documents collected by the U.S. Customs Service. The data cover the movement of goods between foreign countries and the United States.3 The data include government and nongovernment shipments of goods, but they exclude a variety of other diplomatic and military transactions. For imports, the value reported is the U.S. Customs Service appraised value of merchandise—generally, the amount paid for merchandise for export to the United States. Import duties, freight, insurance, and other charges incurred in bringing merchandise to the United States are excluded. Exports are measured by recording the free alongside ship value of merchandise at the U.S. port of export. That value is based on the transaction price, including inland freight, insurance, and other charges incurred in placing the merchandise alongside the carrier at the U.S. port of exportation.

Data on the trade in services is collected primarily by the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) in the U.S. Department of Commerce through mandatory surveys of financial services and other business.4 While the BEA surveys mainly cover U.S. residents’ transactions with unaffiliated foreign residents, in a few cases data on transactions on affiliated foreigners is also gathered—that is, transactions between U.S. parent companies and their foreign affiliates or between U.S. affiliates of foreign companies and their foreign parent companies.5 For the most part, however, transactions with affiliated foreigners are collected in BEA’s surveys of direct investment abroad and foreign direct investment.

|

3 |

For more detailed information, see http://www.bea.gov/bea/newsrelarchive/2005/info0105.htm [accessed January 2006]; see also U.S. Census Bureau (2002). |

|

4 |

For more information, see BEA’s U.S. International Transactions in Private Services: A Guide to the Surveys Conducted by the Bureau of Economic Analysis, available: http://www.bea.gov/bea/ARTICLES/INTERNAT/INTSERV/Meth/itguide.pdf [accessed January 2006]. |

|

5 |

A U.S. parent company—also referred to as “U.S. parent” or “parent”—is a U.S. business that undertakes direct investment abroad. A foreign affiliate of a U.S. parent—also referred to as “affiliate”—is a foreign business in which a U.S. parent has a direct investment interest. A subset of affiliates are majority-owned foreign affiliates in which the combined ownership of all U.S. parents exceeds 50 percent. A U.S. multinational corporation is the combined operations of a parent and its affiliates. |

Foreign Direct Investment and Affiliate Activities

The International Investment Division of the BEA collects and analyzes data on U.S. direct investment abroad, foreign direct investment in the United States, and selected services transactions with unaffiliated foreign persons.6 Direct investment abroad is investment in which a resident of one country obtains a lasting interest in and a degree of influence over the management of a business enterprise in another country. In the United States, the criterion used to distinguish direct investment abroad from other types of investment abroad is the ownership of at least 10 percent of a foreign business enterprise. Foreign direct investment in the United States is determined by the same 10 percent rule and is based on the country of residency of the foreign owner, not on the owner’s citizenship.

Both the financial and operating data and the direct investment position and balance of payments data can be classified by industry of affiliate, by country and industry of the ultimate beneficial owner, and by the country and industry of foreign parent. In addition, the direct investment position and balance of payments data can be classified by the country of each member of a foreign parent group. Annual estimates are made of the U.S. direct investment position abroad and of balance of payments flows between U.S. parents and their foreign affiliates, including capital flows with their components, equity, intercompany debt, and reinvested earnings shown separately. Income and services are available at various levels of country and industry detail.

Prices

To determine the effects of international trade on wages and working conditions, it is not enough to know the value of imports and exports. One also needs to know the prices and the quantities. Prices and costs are the economic signals that drive business and consumer decisions to buy or produce in one or another location. Prices are used to address a number of questions about international trade and the relationship between international trade and the U.S. economy overall, both at a given time and over

|

6 |

For more information, see BEA’s International Investment Product Guide, available: http://www.bea.gov/bea/ai/iidguide.htm [accessed January 2006]; see also Bureau of Economic Analysis (1992) and Mataloni (1995). |

time. The price charged for something depends on the tastes, incomes, and demands of customers. It also depends on the amount of competition in the market. If there is a monopoly, or firms have some market power, then the seller has some control over the price, which will probably be higher than in a perfectly competitive market. Therefore, insofar as offshoring opens up new supplies of factors or goods, it can change prices by eliminating market power that might exist in local or national markets. Analyzing price data can also help address the notion of international competitiveness: how much do U.S. consumers pay for exports relative to imports, expressed as an index value. Prices are key to undertaking econometric research on whether changes in income or change in prices are the more important driver of international trade flows. To analyze the relative competitiveness of domestic and foreign producers of services, U.S. international price data need to be comparable to domestic price data for similar classifications of services transactions. It is difficult to achieve these objectives.

The International Price Program (IPP) was established in 1971 and uses market sale prices and transfer prices, which are market related, for calculating export and import price indexes.7 Sample establishments are chosen for the IPP on the basis of their relative trade value in imports and exports during the course of a year. Establishments are asked to provide prices on a monthly basis. The sample of U.S. exporters is derived from shippers’ export declarations, and the sample of U.S. importers is derived from consumption entry documents. Price data are collected on about 10,000 individual export items and 12,000 import items. These data include few service transactions—mostly related to transportation and travel—and none are available for business and professional service transactions.

Labor Input

The Bureau of Labor Statistics in the U.S. Department of Labor carries out three major survey programs to gather data on wages and employment. The Occupational Employment Statistics Program gathers survey

|

7 |

For more information, see Export and Import Prices, available: http://www.bls.gov/mxp/#item17 [accessed January 2006] and Frequently Asked Questions, available: http://www.bls.gov/mxp/ippfaq.htm#item11 [accessed January 2006]. |

data on wages and employment from approximately 400,000 U.S. establishments annually; the Current Employment Statistics is a survey of payroll records that covers more than 300,000 businesses on a monthly basis; and the Current Population Survey (CPS) gathers information on the labor force status of approximately 60,000 households on a monthly basis.8 The data on jobs in the United States are organized by occupation, by geographic region, by industry, or by more than one criteria—that is, a particular occupation in a given area or industry. General employment data are not designed to isolate job losses attributable to any specific causes.

Data on Services

When offshoring was limited mostly to the production of goods, the measurement of goods transactions provided information about an important cause of changes in the location of work. However, as the economy has become more service oriented, understanding the markets for goods alone is not enough. The emphasis needs to shift from measuring the flow of goods across borders to the measurement of the flow of services across borders. This can be difficult because service work may leave little or no physical trail and often leaves rather incomplete business records. For example, software coding is transmitted to the United States electronically, with no identifiable point of entry and no recorded value, especially for transactions that occur within multinational firms. Since technological developments will continue to reduce the effectiveness of measures at the border, measuring the content of work being done onshore and offshore directly becomes more important. In addition to the problem of measuring value, there is the even more difficult problem of measuring the prices of services.