2

The Evolving Role of Hospital-Based Emergency Care

The emergence of the modern emergency department (ED) is a surprisingly recent development. Prior to the 1960s, emergency rooms were often poorly equipped, understaffed, unsupervised, and largely ignored. In many hospitals, the emergency room was a single room staffed by nurses and physicians with little or no training in the treatment of injuries. It was also common to use foreign medical school graduates in this capacity (Rosen, 1995). In teaching hospitals, the emergency areas were staffed by junior house officers, and faculty supervision was limited (Rosen, 1995). One young medical student in the 1950s described emergency rooms as “dismal places, staffed by doctors who could not keep a job—alcoholics and drifters” (University of Michigan, 2003, p. 50).

Over four decades, the hospital ED has been transformed into a highly effective setting for urgent and lifesaving care, as well as a core provider of ambulatory care in many communities. An extraordinary range of capabilities converge in the ED—highly trained emergency providers, the latest imaging and therapeutic technologies, and on-call specialists in almost every field—all available 24 hours a day, 7 days a week.

The appeal of the modern ED is undeniable—it is in some ways all things to all people. To the uninsured, it is a refuge. To the community physician, it is a valuable practice asset. To the patient, it is convenient, one-stop shopping. To the hospital itself, it is an escape valve for strained inpatient capacity. The demands being placed on emergency care, however, are overwhelming the system, and the result is a growing national crisis. The decrement in emergency care capacity and quality, however, is almost invisible to those outside the system. Few people have regular contact with

the emergency care system, but when serious illness or injury strikes, the system they expect to be there may fail them, with catastrophic results. This chapter explains the increasing demands being placed on hospital-based emergency care, describes the nature of the crisis, and explores how it impacts individuals day to day.

IMBALANCE BETWEEN DEMAND AND CAPACITY

In the decade between 1993 and 2003, the United States experienced a net loss of 703 hospitals, an 11 percent decline. The number of inpatient beds fell by 198,000, or 17 percent, and the number of hospitals with EDs declined by 425, a 9 percent decrease (AHA, 2005b). This sharp decline in capacity was largely in response to cost-cutting measures and lower reimbursements by managed care, Medicare, and other payers (discussed below), as well as shorter lengths of stay and reduced admissions due to evolving clinical models of care.

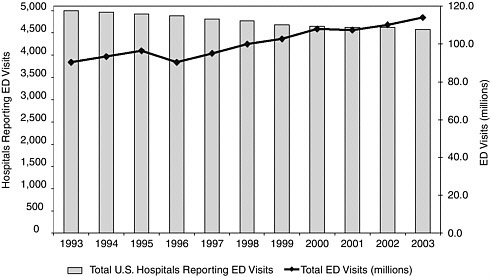

During this same period, the population of the United States grew by 12 percent and hospital admissions by 13 percent. Between 1993 and 2003, ED visits rose from 90.3 to 113.9 million, a 26 percent increase, representing an average of more than 2 million additional visits per year (see Figure 2-1) (McCaig and Burt, 2005). The outcome of these intersecting trends of

FIGURE 2-1 Hospital EDs versus ED visits.

SOURCES: AHA, 2005b; McCaig and Burt, 2005.

falling capacity and rising use was inevitable. By 2001, 60 percent of U.S. hospitals reported that they were operating at or over capacity (The Lewin Group, 2002).

Not only is ED volume increasing, but patients are presenting with more serious or complex illnesses. The U.S. population is aging, and thanks to advances in the treatment of HIV, cancer, and kidney and heart disease, many people live with significant comorbidities and chronic illnesses (Derlet and Richards, 2000; Bazzoli et al., 2003). These patients require more complex and time-consuming workups and treatments.

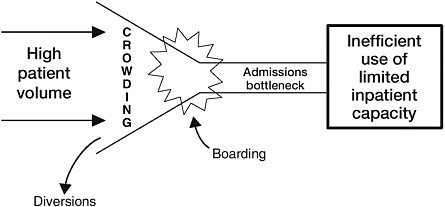

By law, the ED’s front door is always open, and there is growing public demand for its services. Among the normal flow of patients into the ED, some require hospitalization, some are treated and released, some are transferred, and a few die while in the ED. Nationwide, about 13.9 percent of ED patients were admitted to the hospital in 2003 (McCaig and Burt, 2005); this figure represents about 43 percent of all hospital patients in 2002 (Merrill and Elixhauser, 2005). But when a hospital’s inpatient beds are full, the result is a bottleneck to admitting the most severely ill and injured from the ED. As a result, patients who require hospitalization begin to back up in the ED (Andrulis et al., 1991; Asplin et al., 2003). The most common cause of this bottleneck is the inability to admit critically ill patients because all of the hospital’s intensive care unit (ICU) beds are filled (GAO, 2003). When delays in accessing inpatient beds become excessive, these patients are commonly referred to as “boarders” because they are technically inpatients but cannot leave the ED. “Boarder” is a misnomer, however, because it implies that these patients require little care. In fact, ED boarders often represent the sickest patients and the most complex cases in the ED—which is why they require hospitalization. And since these patients cannot be moved upstairs, the ED staff must provide ongoing care while simultaneously evaluating and stabilizing incoming ED patients. High levels of hospital occupancy not only create ED “boarders” but also can dramatically worsen ED crowding if community physicians who are unable to secure a bed for their scheduled admissions start sending patients through the ED instead. In either case, the normal congestion in the ED is increased. The problem is depicted in Figure 2-2.

The result of this imbalance is an epidemic of overcrowded EDs, frequent boarding of patients waiting for inpatient beds, diversion of ambulances, and patients who leave without being seen or leave against medical advice (Kellermann, 1991).

Overcrowding

ED overcrowding is a nationwide phenomenon, affecting urban and rural areas alike (Richardson et al., 2002). In one study, 91 percent of EDs

FIGURE 2-2 Consequences of the imbalance between ED patient volume and inpatient capacity.

responding to a national survey reported overcrowding as a problem; almost 40 percent reported that overcrowding occurred daily (Derlet et al., 2001). Another study, using data from the National Emergency Department Overcrowding Study, found that academic medical center EDs were crowded on average 35 percent of the time. This study developed a common set of criteria for identifying crowding across hospitals based on several common elements: all ED beds full, people in hallways, diversion at some time, waiting room full, doctors rushed, and wait times to be treated of greater than 1 hour (Weiss et al., 2004; Bradley, 2005).

Overcrowding can adversely impact the quality of care in the ED and trauma centers. It can also lead to dangerous delays in treatment in the ED and cause delays in emergency medical services (EMS) transport (Schull et al., 2003, 2004).

Boarding

The most common cause of ED crowding is the boarding of admitted patients in the ED. A Government Accountability Office (GAO) study found that in 2001, 90 percent of hospitals boarded patients for at least 2 hours, and about 20 percent of hospitals reported an average boarding time of 8 hours (GAO, 2003). It is not unusual for patients in a busy hospital to board for up to 24 or even 48 hours. In a point-in-time survey of nearly 90 hospital EDs across the country, 73 percent of hospitals reported boarding two or more patients on a typical Monday evening (ACEP, 2003a). The potential for errors, life-threatening delays in treatment, and diminished overall quality of care is enormous in these situations (Andrulis et al., 1991; Conn, 1993; Litvak et al., 2001; Needleman et al., 2002; Schull et al., 2004).

Ambulance Diversions

Another indication of the degree of ED crowding is the frequency of ambulances being diverted to alternative hospitals—a now common, if not daily, event in many major cities. According to the American Hospital Association (AHA), nearly half of all hospitals (46 percent), 68 percent of teaching hospitals, and 69 percent of urban hospitals reported time on diversion in 2004 (AHA, 2005b). A GAO study found that 69 percent of hospitals went on diversion at least once in 2001 (GAO, 2003). A Massachusetts Department of Public Health survey indicated that 67 of 76 hospitals responding to the survey “either diverted or employed special procedures” during one week in February 2001 to meet the demands on the ED (Massachusetts Department of Public Health, 2001). A report using data from the 2003 National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey indicated that 501,000 ambulances were diverted in 2003 (Burt et al., 2006).

To date, data on the health outcomes associated with diversion are limited. A 2002 study by the Joint Commission for Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO) revealed that over half of all ED events described as sentinel were caused by delayed treatment (Delays in Treatment, 2002). According to an AHA survey, hospitals reporting 20 percent or greater time spent on diversion had longer wait times for treatment by a physician, longer average lengths of stay in ED treatment, longer wait times for transfer from the ED to an acute or critical care bed, and longer wait times for transfer from the ED to a psychiatric bed (The Lewin Group, 2002). A study of trauma patients in Houston found that the numbers of deaths among these patients were consistently greater than average on days with high levels of diversion, but the differences were not statistically significant (Begley et al., 2004). In Canada, reports of a patient’s death while en route to an open hospital because his local ED was on diversion raised questions about the legality of ambulance diversion (Walker, 2002).

Ambulance diversions indicate a lack of ability to handle surges in the need for emergency care. If operating at a normal level forces ambulances to be diverted on a regular basis, it may be expected that in the event of a terrorist attack, natural disaster, or other severe and widespread medical emergency, the emergency system would be unprepared for the volume and severity of ED visits (Moroney, 2002).

Patients Who Leave Without Being Seen

In 2003, about 1.9 million ED patients left without being seen by a physician or other emergency care provider; this figure represents 1.7 percent of all ED patients, versus 1.1 percent in 1993 (McCaig and Burt, 2005). While the majority of these patients had low acuity levels, that was

not always the case. Studies have shown that some of these patients were in need of immediate medical attention (Baker et al., 1991; Fernandes et al., 1997). One study revealed that those who left without being seen were twice as likely to report pain or a worsening of their problem as those who were seen. Another study found that 27 percent of those who left without being seen returned to an ED, and 4 percent required subsequent hospitalization (Bindman et al., 1991).

Crowding and wait times are important predictors of patients leaving the ED without being seen (Fernandes et al., 1994; Hobbs et al., 2000). One study found that the numbers of such patients increase as ED utilization rises above capacity (Quinn et al., 2003). In addition to patients who leave without being seen, another study found that about 1.2 million or 1 percent of all ED patients leave “against medical advice,” in other words, once assessment or treatment has begun, but before it has been completed (McCaig and Burt, 2005).

THE EMERGENCY DEPARTMENT AS A CORE COMPONENT OF COMMUNITY AMBULATORY CARE

The “Safety Net of the Safety Net”

Hospital EDs are the provider of last resort for millions of patients who are uninsured or lack adequate access to care from community providers. The number of uninsured in the United States is now estimated to exceed 45 million and continues to climb (DeNavas-Walt et al., 2005); the number is expected to reach 51.2–53.7 million by 2006 (Simmons and Goldberg, 2003). Some suggest that an additional 29 million Americans are underinsured, lacking sufficient coverage for essential medical care (O’Brien et al., 1999).

The Institute of Medicine (IOM) report America’s Health Care Safety Net: Intact but Endangered called attention to the growing threats to the nation’s health care safety net—increasing numbers of uninsured; erosion of direct and indirect subsidies to providers, including Medicaid Disproportionate Share Hospital (DSH) payments and cost-based reimbursement to Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs); and the continuing growth of Medicaid managed care, which lowers payments and diverts patients from core safety net providers (IOM, 2000). The IOM’s six-part Insuring Health series comprehensively examined the consequences of uninsurance in the United States. A Shared Destiny: Community Effects of Uninsurance, one of the reports in that series, demonstrated the impact of uninsurance on the demand for safety net services and in particular the burden this places on an overextended emergency care system (IOM, 2003). Many of

these uninsured patients have no regular source of care and fail to realize the benefits associated with having a primary care provider. An earlier IOM Report, Primary Care: America’s Health in a New Era, examined the features of primary care—including integration of medical services; coordination of physical, mental, emotional, and social concerns; and sustained clinician–patient relationships—and documented the decrements in quality of care and health that result from inadequate public access to primary care (IOM, 1996). With limited access to community-based alternatives to the emergency system—public clinics, specialists, psychiatric facilities, and other services—many of these people turn to the emergency care system when in medical need, often for conditions that have worsened because of a lack of primary care.

Because the emergency care system is the only component of the nation’s safety net that must provide care to everyone, regardless of insurance coverage or ability to pay, hospitals have no alternative but to try to absorb these patients as best as they can. Community-based services, when faced with high demand, can restrict access. Community health centers typically operate only during business hours, maintain long waiting lists, and may lack significant specialty and diagnostic services that are required to fully address their patients’ needs. EDs, by contrast, have no such options—they are mandated to serve all who come. Without the ED to fall back on, other community safety net services would be equally overwhelmed. Thus, the emergency care system truly has become the “safety net of the safety net.”

Use of the ED for Nonurgent Care

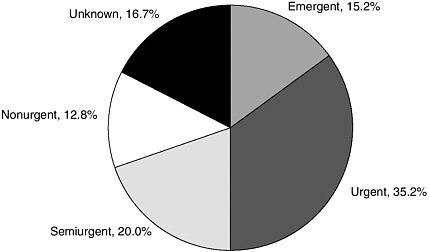

Just over half of ED visits in 2003 were categorized as emergent or urgent, translating into a need for care within 15 minutes to 1 hour of arrival at the ED, while about 33 percent of visits were categorized as semiurgent or nonurgent, requiring attention within 1 hour or 24 hours, respectively (McCaig and Burt, 2004) (see Figure 2-3). Defining ED care as nonurgent or medically unnecessary is controversial because the terms are difficult to define and may vary depending on who is defining them. Is necessity determined by the patient’s signs and symptoms at the time of arrival, or by the diagnosis at the time of hospital admission or discharge from the ED? A patient with chest pain would certainly consider this a proper reason to seek ED care, but a patient discharged with a diagnosis of heartburn might be judged by his insurer to have made an inappropriate ED visit. How likely is it that a physician, patient, and insurer will agree on the level of urgency of any given case? Around these gray areas, however, most would agree that there are patients who could be treated as well or better in a different setting if this care were available.

FIGURE 2-3 Percent distribution of ED visits by the immediacy with which patients should be seen, 2003.

SOURCE: McCaig and Burt, 2005.

Other components of the health care system that serve large safety net populations have received substantial government support. For example, community health centers are funded by a federal grant program under Section 330 of the Public Health Service Act and are administered by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA). They received more than $1.7 billion in federal funding in 2005 and served an estimated 14 million patients. In fiscal year 2002, President Bush proposed a 5-year, $780 million initiative to increase the number of community health center sites throughout the nation in order to reach an additional 6.1 million patients by the end of 2006. By the end of 2005, 428 new sites had been established, and many more had increased their medical capacity (HRSA Bureau of Primary Health Care, 2006).

A recent report of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) revealed that EDs represent an important component of the ambulatory care system (12.7 percent of all visits) (Schappert and Burt, 2006). The proportion is much higher in many rural and urban communities where the local ED is the principal provider. Despite its importance in providing ambulatory care and the legal requirement to accept all patients regardless of insurance coverage or ability to pay, hospital emergency care receives little direct federal support.

Why Nonurgent Patients Use the ED

Research has identified several important determinants of nonurgent utilization of the ED. These include financial barriers to and limited availability of alternative sources of care, referrals to the ED by community physicians, and patients’ preference for the ED over other alternatives.

Financial barriers Studies have shown that a significant number of patients use the ED for nonurgent matters because of financial barriers. While often unable to access private physician practices, uninsured patients do have access to public health clinics operated by local and county health departments, including FQHCs. But these clinics are limited in number and geographic distribution. In addition, they may have limited hours, long waits, and queues for new patients. Unlike EDs, they are neither typically open around the clock nor required by law to accept all who come. They may also have limited services. For example, many provide primary care services but lack the resources to provide specialty care and diagnostic services. Results of a recent study suggest that expanding primary care capacity may actually increase demand for ED care (Cunningham and May, 2003). According to the authors, patients with access to primary care are more likely to seek specialty care and diagnostic services.

Although Medicaid beneficiaries have a source of payment for medical care, the rates of reimbursement are so low that the number of office-based practitioners who are willing to accept such patients is low (The Medicaid Access Study Group, 1994). One study (Oster and Bindman, 2003) found that uninsured and Medicaid patients have higher rates of ED utilization and are less likely to have a follow-up visit scheduled with a regular physician. In another study, research assistants posing as Medicaid patients attempted to secure appointments with clinics and physician practices. Fully 56 percent of these providers declined to give an appointment, and the most prevalent reason given was “not accepting Medicaid patients.” When asked for an alternative, most either offered none or advised the caller to “go to an emergency room” (The Medicaid Access Study Group, 1994). Similar barriers to follow-up care exist as well, even after an ED visit for a serious health problem (Asplin et al., 2005). Research assistants posing as ED patients telephoned physician offices and clinics to schedule an urgent follow-up visit for a serious problem diagnosed in the ED (pneumonia, severe hypertension, or suspected ectopic pregnancy). When callers stated that they had private insurance coverage, they were almost twice as likely to get an appointment as the same callers when they stated that they were covered by Medicaid, and about 2.5 times more likely to get an appointment than when they stated a willingness to pay $20 up front and arrange for complete payment later. Of note, nearly 98 percent of clinics specifically

inquired about the caller’s ability to pay, but only 28 percent inquired about the caller’s health.

One consequence of Medicaid patients’ lack of access to primary care is greater reliance on the ED. Medicaid recipients use the ED more than any other group, and their rate of utilization is increasing—81 visits per 100 persons in 2003, versus 65.4 per 100 the year before. This is double the rate of the uninsured population (41.4 percent) and nearly four times that of privately insured patients (21.5 percent) (McCaig and Burt, 2005). All but privately insured individuals also increased their utilization rates from the year before (McCaig and Burt, 2004, 2005). Numerous studies have also found that Medicaid patients disproportionately use the ED for nonurgent conditions, often relying on the ED as their primary source of care (Cunningham et al., 1995; Liu et al., 1999; Sarver et al., 2002; Irvin et al., 2003b). This phenomenon appears to be due largely to a lack of access to care in other settings.

Limited availability of alternative sources of care Even in the absence of financial barriers, patients may use the ED because of limited access to alternative sources of care. Having a usual source of care can deter utilization of the ED for nonurgent purposes (Petersen et al., 1998), but even patients with a usual source of care frequently use the ED after hours when clinics and physician offices are closed. Recent trends in utilization indicate that insured patients, who are less likely to face financial barriers, are using the ED in larger numbers (Cunningham and May, 2003). The most common reason “walk-in” patients seek care in the ED is because they are experiencing painful or worrisome symptoms that they believe require immediate evaluation and treatment (Young et al., 1996).

The ED as an adjunct to physician practices There is evidence that physicians and clinics are increasingly using the ED as an adjunct to their practices, referring patients there for a variety of reasons, including their own convenience after regular hours, reluctance to take on complicated cases, the need for diagnostic tests that they cannot perform in the office, and liability concerns (Berenson et al., 2003; Studdert et al., 2005). In a three-site study in Phoenix, Arizona, researchers found that while two-thirds of patients had not contacted a health professional prior to their ED visit, 80 percent of those who had done so had been referred to the ED (St. Luke’s Health Initiative, 2004). The Medicaid Access Study Group found that a majority of clinics that declined to see Medicaid patients with minor problems failed to offer any advice about alternatives. The second most common option was to tell the caller to seek care in an ED. A national study of ambulatory use of hospital EDs revealed that 19 percent of “walk-in” patients had been instructed to seek care in the ED by a health care provider (Young et al.,

1996). This phenomenon, sometimes called “physician deflection,” is likely to accelerate in the future because primary care offices will be unable to keep pace with the technological advances required to address complex patient needs. Office physicians may consider potentially acute patients to be safer in the ED, and therefore refer such patients directly to the ED even if appointments are available. In addition, referral to the ED has sometimes become the only way to refer patients to certain specialists, who refuse Medicaid patients in many cases. Chronic disease management, medication management, counseling, and case management resources, on the other hand, are aspects of care that primary and specialty care ambulatory practices should be able to provide as an alternative to the ED.

Patient preference Patients are increasingly using the ED for the convenience of obtaining timely resolution of health care problems (Young et al., 1996; Guttman et al., 2003). Some patients use the ED if they feel they need immediate attention but cannot see their primary care provider within 24 hours (Stratmann and Ullman, 1975; Andren and Rosenqvist, 1985). Patients who try to reach their physician by phone in the evening or on weekends may have difficulty getting through or may be instructed to use the ED. Patients whose primary care providers have extended evening or weekend office hours have been found to have lower rates of ED utilization (Lowe et al., 2003).

Patients may also prefer the ED if they believe it is the best place to obtain access to specialized equipment (Roth, 1971; Smith and McNamara, 1988; Brown and Goel, 1994). Increasingly, admitting physicians are insisting that EDs complete highly detailed workups before they will admit a patient to the hospital. This may explain in part the increasing use of diagnostics such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computer-assisted tomography (CAT) scans in the ED—up 103 percent from 1992–1999 according to CDC. Some patients may also view the ED as a convenient site for one-stop shopping for medical care. Even with a wait of 2 or more hours, patients can have all of their needs met in a single visit to the ED, and possibly avoid a much longer total time spent seeking care and obtaining diagnostic testing from multiple providers.

Concerns About Nonurgent Utilization

The delivery of nonurgent care in the ED is of concern for three reasons. First, the primary care delivered in the ED may be of lower quality than that in other settings. The ED is designed for rapid, high-intensity response to acute injuries and illnesses. It is fast-paced and requires intensive concentration of resources for short durations. Such an environment is ill suited to the provision of primary and preventive care (Derlet and Richards, 2000).

Physicians in the ED typically do not have a relationship with the patient, often lack complete patient medical records, face constant interruptions and distractions, and have no means of patient follow-up. Further, because they have low triage priority, these patients have extremely long wait times—sometimes 6 hours or more.

Second, nonurgent ED utilization may be less cost-effective than care provided in other settings. EDs and trauma centers are expected to provide a full array of services around the clock, and the fixed costs associated with maintaining this readiness can be substantial. On the other hand, this standby capacity is likely to result in low marginal costs, making it efficient to provide nonurgent care in the ED, at least during slack periods. The literature is mixed on this issue. Some studies support the notion that nonurgent care costs in the emergency setting may be substantially higher than those in a primary care setting (Fleming and Jones, 1983; White-Means and Thornton, 1995). Greater costs in the former setting may result from the frequent lack of patient records and the inability to construct a patient history, which result in a high frequency of full workups (Murphy et al., 1996). ED charges for services for minor problems have been estimated to be two to five times higher than those incurred in a typical office visit (Kusserow, 1992; Baker and Baker, 1994), resulting in $5–7 billion in excess charges in 1993 (Baker and Baker, 1994). While studies probably overestimate these excess costs, they are nevertheless substantial. Bamezai and colleagues (2005) used data on all California hospitals with EDs from 1990 to 1998 to calculate average outpatient ED costs ranging from $116 to $130 for nontrauma EDs and $171 to $215 for trauma EDs, depending on volume. In contrast, Williams (1996) studied a sample of six hospitals in Michigan and found that average and marginal costs of ED visits were quite low, especially for those classified as nonurgent—perhaps below the cost of a typical physician visit. However, if hospitals build additional high-cost ED capacity as a result of the increased use of the ED for nonurgent care, the true cost of providing such care in the ED will be much higher than the marginal or average cost of treatment.

Third, nonurgent utilization may detract from the ED’s primary mission of providing emergency and lifesaving care. Regardless of their efficiency on average, EDs do not have unlimited resources. When the ED becomes saturated with patients who could be cared for in a different environment, fewer resources, including physicians, nurses, ancillary personnel, equipment, time, and space, are available to respond to emergency cases.

Identifying Nonurgent Visits

Identifying nonurgent visits is not a simple matter. The inability of patients to distinguish accurately between emergent/urgent and nonurgent

conditions has been documented (Lowe and Bindman, 1997). Patients may overestimate the urgency of their condition—in one study, 82 percent of nonurgent patients considered their condition to be urgent (Gill and Riley, 1996). On the other hand, many nonurgent patients understand that their condition is not urgent; they use the ED for a variety reasons outlined above, knowing that they can receive nonurgent care. In a case study of over 400 individuals using the ED, researchers found that more than one-third described their condition as other than an emergency (Guttman et al., 2003).

An even more important question is how many urgent patients underestimate the urgency of their condition, a miscalculation that could delay care and have catastrophic consequences. A survey of patients across 56 hospital EDs nationwide found that 5 percent of patients who viewed their condition as nonurgent were subsequently admitted to the hospital (Young et al., 1996). In another study, using National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NHAMCS) data from 1992–1996, 4 percent of nonurgent patients were subsequently hospitalized (Liu et al., 1999). These studies probably underestimated the magnitude of the problem as they did not account for patients who never show up at the ED because they underestimate the urgency of their condition. Further, indirect evidence of patients underestimating the urgency of their condition is provided by the failure to call 9-1-1 in cases of heart attacks and other life-threatening emergencies (NHAAP Coordinating Committee, 2004), although other factors, such as feelings of embarrassment and loss of control, also play a role in the failure to call EMS.

The bottom line is that attempts to eliminate nonurgent visits should not discourage patients from seeking help at the ED, in particular when their condition lies in the gray area where the distinction between life-threatening emergencies and nonurgent acute episodes is blurred. It is important for patients to be able to choose the ED if they are uncertain about where on this spectrum their particular condition falls.

Scheduled Versus Unscheduled Visits

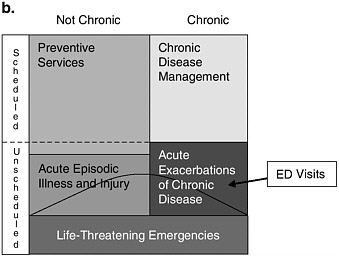

A useful way to conceptualize the utilization of ED services is to consider them within the broad context of all health care services within a community. Services can be categorized according to whether they are scheduled or unscheduled. Scheduled services are those that are predictable and planned; they include regular doctor visits and scheduled surgeries, for example. Unscheduled services are those that are unpredictable and irregular because of unexpected injuries or illnesses, such as a heart attack, trauma from a car crash, or a sports injury (Asplin et al., 2003).

Scheduled and unscheduled visits are illustrated in Figures 2-4a and

2-4b. In each figure, the area of the entire box represents all health care visits. The blocks on the right side represent services that are related to preexisting chronic conditions, for example, asthma or congestive heart failure, while those on the left side are not related to a chronic condition. The top two blocks represent visits for primary care services such as preventive care and management of chronic conditions, which are largely scheduled in nature. The middle two blocks represent visits that are typically unscheduled, including those for acute exacerbations of chronic disease, such as a severe episode of asthma, and acute episodic illness and injury, which may include a case of the flu or a sports injury. (Note that a small proportion of preventive services is included in unscheduled visits.) The bottom block represents life-threatening emergencies, such as heart attacks and serious traumatic injuries.

The ED is one of many sites in the health care delivery system that might provide the types of services in the top four blocks, while the bottom block is, ideally, the exclusive domain of EDs and trauma centers. The area beneath the dashed line indicates care that is provided within the ED. The vast majority of scheduled care will occur outside of the ED at provider locations throughout the community, such as physician offices, diagnostic facilities, and hospital inpatient facilities. Likewise, sites outside of the ED will deliver a large proportion of unscheduled care for both acute episodic illness and injury and acute exacerbations of chronic disease. The relative size of each block within the figures, along with the location of the line depicting the ED’s role, will vary depending on a number of factors. Aday and Anderson (1974) proposed a model of community access to medical care that categorizes these as predisposing factors, such as the health status of the community and the amount of preventive care that is provided, and enabling factors, which increase or reduce barriers to access such as insurance coverage and the supply of physicians and other services.

Figure 2-4a represents a hypothetical distribution of medical services between EDs and other providers that is typical of many communities today. Preventive services and chronic disease management are provided mainly outside the ED, while acute illnesses and exacerbations of chronic disease are often treated in the ED. One can envision variations of Figure 2-4a based on differences among communities or groups of patients. For example, suburban and rural community hospitals are likely to look quite different from urban safety net hospitals; the latter have been shown to have 25 percent more nonurgent cases and 10 percent more patients presenting with emergent conditions that are treatable by primary care (Burt and Arispe, 2004).

The relative dimensions of the blocks in the figures are also likely to vary over the 24-hour cycle. There is evidence, for example, that a significant portion of the nonurgent care that is provided in the ED, including

visits associated with chronic care management and acute exacerbations of chronic disease, takes place during evenings and weekends, when alternative providers are not available.

Communities with strong access to preventive care and chronic disease management services outside the ED may have less demand for such care in the ED. More important, by improving health and reducing the frequency of acute episodes, it may be possible to reduce the proportion of unscheduled care in the community. Improved preventive care may also reduce the need for chronic disease management itself. These effects are shown in Figure 2-4b as a smaller row representing unscheduled care, a smaller column representing chronic care visits, and the dashed line indicating a smaller amount of care delivered in the ED. Better access to chronic care management and preventive care may also reduce the amount of care for life-threatening emergencies, also indicated in Figure 2-4b by the reduced size of the bottom block. For example, communities that do a better job of managing asthma care will have fewer and less severe acute asthma attacks among the population.

This picture is complicated somewhat by Cunningham and Hadley’s (2004) observation that increased access to community clinics resulted in greater use of the ED, presumably because enhanced primary care heightened the demand for a limited supply of specialized and diagnostic care. The above discussion also ignores a potentially important long-term effect of prevention and chronic disease management—that increasing life spans may result in a growth in the amount of medical care demanded overall.

Other versions of Figures 2-4a and 2-4b might include a “nightmare scenario” combining the anticipated burden of chronic disease due to the aging of the baby boomers with a system that continued to manage chronic disease in a disorganized and uncoordinated fashion. In this scenario, the entire area of the figures would be larger, and the amount of care provided in the ED, especially for acute exacerbations of chronic disease, would be extremely high.

REIMBURSEMENT FOR EMERGENCY AND TRAUMA CARE

Substantial evidence demonstrates that reimbursement to safety net hospitals is inadequate to cover the costs of emergency and trauma care. Of the 114 million ED visits in 2003, 36 percent of patients had private insurance, 21 percent were enrolled in Medicaid or the State Children’s Health Insurance Program (SCHIP), and 16 percent were covered by Medicare (see Figure 2-5). The payer mix varies widely across hospitals, however, and differences in that mix can have a substantial impact on a hospital’s financial condition. Some hospitals treat a large number of uninsured patients, many of whom are unable to pay for their care. To address this gap, the Centers

FIGURE 2-5 Payment sources for ED visits, 2003.

SOURCE: McCaig and Burt, 2005.

for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) provides DSH payments to these hospitals, as well as payments for treating undocumented aliens. A number of states also provide additional support to emergency and trauma care systems through general revenues or special taxes.

The Uninsured, or Self-Pay

As discussed earlier, the uninsured use the ED at a significant rate: they made about 41.4 visits per 100 individuals in 2003, and they represented 14.1 percent of all ED utilization in 2003 (McCaig and Burt, 2005). A recent study documented that ED use by uninsured patients is increasing (Cunningham and Hadley, 2004). The rate of reimbursement for services provided to these patients is difficult to quantify but is known to be quite low, and these patients account for a large proportion of the losses associated with hospital ED and trauma care.

Medicaid

Medicaid payment methods vary by state. The most common method is fee-for-service, which is used in 23 states. Second most common is a cost-based reimbursement system. A prospective payment system similar to that of Medicare (Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, 2003) is used by some states, and many states use a combination of methods.

Medicaid payments are supplemented by DSH payments to offset losses for hospitals with high levels of uncompensated care. These payments are extremely variable, and in many states, DSH money is diverted to wholly unrelated areas, such as long-term care (Ku and Coughlin, 1995; IOM, 2003). It is of note that hospitals that serve a large proportion of Medicaid patients but few uninsured will fare better than hospitals that serve few Medicaid patients but a large proportion of uninsured (Fagnani and Toblert, 1999; IOM, 2003). Current legislative proposals would fold DSH payments into block grants, further diluting their contribution to the funding of safety net emergency and trauma care. According to AHA, 73 percent of hospitals lose money providing emergency care to Medicaid patients, while 58 percent lose money on care provided to Medicare patients (AHA, 2002).

Medicare

Medicare enrollees represent 16.3 percent of ED utilization and visit the ED at a rate in between that of Medicaid and uninsured patients—52.4 per 100 enrollees in 2003 (McCaig and Burt, 2005). Medicare reimburses hospitals through a prospective payment system that pays a set amount for a given type of care. Over 80 percent of ED care falls under the five emergency care Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes that are based on the intensity of the service—from Code 99281 for a self-limited or minor problem through Code 99285 for an ED visit of high severity that requires urgent evaluation and poses an immediate and significant threat to the patient’s life or physiological function (AMA, 2003). When ED patients are admitted to the hospital, however, the emergency care payment is subsumed by the hospital diagnosis-related group (DRG) payment instead of the CPT-based payment being used. Medicare considers all emergency care provided within 72 hours prior to a hospital inpatient admission as related to that admission. From the perspective of the hospital’s accounting ledger, the ED may appear to be less profitable because the hospital can readily tabulate the costs of operating the ED, but revenue for admissions that enter the hospital through the ED is credited to its inpatient units (MedPAC, 2003).

Medicare DSH payments are a percentage addition to the basic DRG payments and are applied to hospitals that provide a certain level of uncompensated care. The calculation of DSH payments is based on a complex formula (CMS, 2004).

Private Health Insurance

Privately insured individuals represent the largest single group making visits to the ED but have the lowest rate of use (21.5 per 100) (McCaig and Burt, 2005). Private insurance companies use a wide variety of re-

imbursement methods, and payment rates generally are not known to the public. In some cases, services are not reimbursed because of denial of payment by the insurer. According to guidelines established in the Medicare Modernization Act, payment is to be based on Medicare’s “reasonable and necessary” requirement on the basis of signs and symptoms at the time of treatment, not retrospective evaluation of the primary diagnosis (ACEP, 2003b). Nonetheless, a recent study of two health maintenance organizations (HMOs) in California found that one of the most frequent categories of denial was emergency care (between 16 and 17 percent of coverage requests were denied) (Kapur et al., 2003). The reason cited for almost every denial was that the visit was not deemed an emergency according to the “prudent layperson standard.”1 But a follow-up study found that patients prevailed in over 90 percent of appeals involving ED care (Gresenz and Studdert, 2004).

Payment for services may be denied for a number of reasons. Insurers may have some incentive to delay physician credentialing because doing so may offer a legally valid reason to deny payment if patients have not seen a “participating provider.” There may also be some instances in which payment is denied if a patient’s primary care provider was not contacted, although the more stringent forms of gatekeeping of the 1990s have diminished.

Undocumented Immigrants

Undocumented immigrants, many of whom are uninsured and have no means of paying for medical expenses, represent a significant burden for hospitals and other providers throughout the United States, particularly in states that border Mexico. The estimated annual cost of emergency care for just the 28 counties along the border in Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, and California is $232 million (MGT of America, 2002). A recent change in Medicare provides a special funding mechanism to assist providers serving large numbers of undocumented immigrants. Section 1011 of the Medicare Modernization Act provides $250 million per year for fiscal years 2005–2008 in payments to hospitals, certain physicians, and ambulances for unreimbursed emergency health services provided to undocumented and other specified immigrants (CMS, 2006).

Trends in Reimbursement

According to data from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS),2 there is a growing gap between charges and payments for emergency services. The average combined charge for physician and hospital/facility services in the MEPS 2001 sample was $943, a 49 percent increase since 1996. The average payment was $492, a 29 percent increase since 1996. Thus, payments have increased but have not kept pace with charges, with average reimbursement rates declining from approximately 60 percent in 1996 to 52 percent in 1998.3

Financial Impact on Emergency and Trauma Care

In most hospitals, if reimbursements fail to cover ED and trauma costs, these operations are cross-subsidized by the admissions that originate in the ED. But uncompensated care is an extreme burden at many large urban safety net hospitals that have large numbers of uninsured patients (Burt and Arispe, 2004). These hospitals often bear an increasing burden as surrounding community hospitals go on diversion to preserve the relative calm of their EDs. Further, surrounding hospitals tend to transfer complex, high-risk patients to the large safety net hospitals for specialized care (Reilly et al., 2005). In many cases, the condition of these patients has deteriorated considerably since their arrival at the first hospital (Byrne and Bagan, 2004). The spate of hospital, ED, and trauma center closures in California and elsewhere (see Chapter 1) is indicative of the severity of the problem (Lambe et al., 2002; Vogt, 2004; Melnick et al., 2004; Kellermann, 2004; Fields, 2004; Dauner, 2004).

Public hospitals, which provide a substantial amount of safety net care, are especially hard hit. A survey conducted by the National Association of Public Hospitals (NAPH) found that while NAPH members represent only 2 percent of all U.S. hospitals, they provide almost a quarter (24 percent) of all uncompensated hospital care nationwide (Huang et al., 2005); 21 percent of NAPH hospitals’ costs were uncompensated, versus 5.5 percent for all hospitals. For 56 percent of those hospitals, Medicaid payments did not cover costs, and for 90 percent of NAPH hospitals, Medicare payments did not cover costs—in the aggregate, Medicare covered only 80 percent of costs. A

significant portion of the losses of public hospitals was associated with the provision of emergency and trauma care; on average, these hospitals had three times more emergency visits than all U.S. acute care hospitals.

While these problems are national in scope, certain localities have experienced particular problems. For example, Los Angeles has seen nine hospital EDs close since 2003 (Robes, 2005), bringing its total ED closures to over 60 in the last decade (California Medical Association, 2003). That figure includes the recent closure of the East Los Angeles hospital, in operation for 90 years and serving primarily the Latino population. It lost more than $800,000 in ED operations in 2001–2002 (Coalition to Preserve Emergency Care, 2004). In addition, Los Angeles has lost 10 trauma centers since the 1980s (Chong, 2004). These closures reflect a statewide trend in ED financial losses: California EDs lost $460 million statewide in fiscal year 2001–2002, an increase of 18 percent over the year before and 58 percent since fiscal year 1998–1999 (California Medical Association, 2004).

Trauma services represent a particular financial drain on safety net hospitals. In Houston, for example, the two level I and five level III trauma centers had $32 million in unreimbursed costs in fiscal year 2001, resulting in losses of $19 million (Bishop+Associates, 2002a). Statewide, the state’s 21 trauma centers had total losses of $181 million in direct trauma costs, not including standby/readiness costs (Bishop+Associates, 2002b).

A separate study examined trauma costs in five public and five private/ nonprofit trauma centers in Texas in fiscal year 2001. Public trauma centers had a median operating loss of $18.6 million, a 54 percent increase over the previous year. Private/nonprofit trauma centers had a median operating loss for trauma care of $5.5 million. These losses were attributed to the increasing number of uninsured in Texas, which leads the nation with 24 percent of its population uninsured, and a decline in DSH payments of $26 million relative to the previous year (Clifton, 2002).

In Florida, an analysis of 18 of the state’s 21 trauma centers in 2003– 2004 found that these centers had an aggregate loss of $92 million in combined uncompensated direct care and standby/readiness costs (e.g., the costs of maintaining standby ICU facilities, staff, and on-call specialists for trauma services around the clock) (The University of South Florida, 2005). One study measured three components of the cost of maintaining readiness for trauma care—around-the-clock specialist coverage, verification, and outreach and prevention. The median annual costs were $2.7 million, with the majority of this figure consisting of stipends for specialist coverage (median = $2.1 million) (Taheri et al., 2004).

Consistent with all of these findings was a study of a single medical center in 1999 that found the mean reimbursement for trauma care to be only 36 percent of charges. No reimbursement was obtained for 26 percent of patients, and reimbursement did not cover costs for 56 percent of patients.

Reimbursement was significantly lower for transfers than for other trauma cases, indicating the potential dumping of patients from community hospitals (Lanzarotti et al., 2003). In contrast to these findings for safety net hospitals, one study found that trauma services contributed substantially to the profitability of a hospital with a favorable payer mix—43 percent of trauma patients in this study had private insurance (Breedlove et al., 2005).

The evidence suggests that the burden of providing uncompensated services is placing communities at risk by failing to ensure the continued financial viability of a critical public safety asset—the 24-hour availability of critical lifesaving emergency and trauma care services. Consequently, the committee believes that the emergency care system requires a special funding source, separate from the regular DSH formula, to compensate hospitals and physicians adequately for the burden of providing services to uninsured and underinsured populations. To ensure the continued viability of a critical public safety function, the committee recommends that Congress establish dedicated funding, separate from Disproportionate Share Hospital payments, to reimburse hospitals that provide significant amounts of uncompensated emergency and trauma care for the financial losses incurred by providing those services (2.1).4

The committee believes that accurate determination of the optimal amount of funding to allocate for this purpose, which could run in the hundreds of millions of dollars, is beyond its expertise, but that the government must begin to address this issue immediately. The committee therefore recommends that Congress initially appropriate $50 million for the purpose, to be administered by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (2.1a). The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services should establish a working group to determine the allocation of these funds, which should be targeted to providers and localities at greatest risk; the working group should then determine funding needs for subsequent years (2.1b). Implementation of this recommendation would help staunch the loss of ED capacity in many communities, protect nearby hospitals from a domino effect of spikes in demand, and help ensure the continued viability of the nation’s vital emergency and trauma system. The new funding, however, should be targeted only to hospitals that provide a substantial amount of unreimbursed care to uninsured or underinsured patients in their EDs. Also, this new funding should be tied to hospital performance reporting, participation in coordinated regional systems, improvements in efficiency, reduced boarding and diversion, and improved quality of emergency and trauma care.

|

4 |

The committee’s recommendations are numbered according to the chapter of the main report in which they appear. Thus, for example, recommendation 2.1 is the first recommendation in Chapter 2. |

State Funding for Emergency and Trauma Care Capacity

EMS and emergency and trauma care are often supported through local and state taxes, but only a handful of states have established dedicated funding sources to support emergency care. A summary of funding sources used by the states is shown in Table 2-1. Maryland, for example, imposes a surcharge on motor vehicle registration fees to fund its statewide trauma care and EMS system (National Conference of State Legislatures, 2005). Pennsylvania uses fees from the accreditation process to support a state agency charged with verifying and accrediting all trauma centers on a 3-year basis. In addition, this agency must meet or exceed the standards for trauma centers, programs, providers, data reporting, and performance improvement of the American College of Surgeons. The results of the process are public and reported to the state department of health. Pennsylvania guaranteed support to its trauma care system by modifying its insurance statutes to ensure that accredited trauma centers would receive hospital and professional reimbursement at the charges level, rather than the more common and lower Medicare level, for all motor vehicle crash–related care and workmen’s compensation patients.

Other states rely on a wide range of funding mechanisms. California collects funds from traffic fines, but in the last election, voters declined to impose an additional 3 percent surcharge on telephone bills to support EMS. Ohio uses penalties from failure to wear a seat belt, license reinstatement fines, and forfeited bails. Wisconsin has considered adding $1 to the vehicle registration or driver’s license renewal fee. Surcharges for 9-1-1 phone service have also been used to generate funds to subsidize trauma care. Firearms registration and fines for illegal discharge of firearms are two other potential sources of subsidies that are directly related to the incidence of trauma. It is extraordinary that more states do not support EMS and trauma and emergency care in this manner. The situation may relate to the wide gap between public perception and the reality of the emergency care system. A recent survey found that the public has extremely high expectations of the system but a limited appreciation of the problems that exist (Harris Interactive, 2004).

CHALLENGES OF CARE FOR MENTAL HEALTH CONDITIONS AND SUBSTANCE ABUSE

Patients with mental health conditions and substance-abuse problems represent a small proportion of ED utilization, but they place an inordinate burden on the emergency care system. There is also evidence that the psychiatric and substance-abuse care received in EDs is sometimes less than optimal. On the other hand, it fills a critical need, as the broader health system often fails to provide adequate access to this care.

TABLE 2-1 Revenue Sources to Fund Trauma Care, Organized by Topic

|

Source |

AZ |

CO |

FL |

IL |

KS |

MD |

MI |

NE |

OH |

OK |

PA |

TX |

UT |

VA |

WA |

|

911 System Surcharges |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

Controlled Substances Act Violations |

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Court Fees, Fines, and Penalties |

|

|

|

X |

X |

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

Intoxication Offenses—Not Limited to Motor Vehicles |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

Motor Vehicle Fees, Fines, and Penalties |

|

X |

X |

X |

|

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

X |

X |

|

|

X |

|

|

|

X |

|

X |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

X |

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

Sales Surtax |

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Tobacco Tax |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Trauma Facility Penalty |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Tribal Gaming |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Weapons Violations |

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

SOURCE: HRSA, 2004. |

|||||||||||||||

Care for Mental Health Conditions

Patients with mental illness represent a considerable and growing number of all ED visits. Between 1992 and 2001, the proportion of all ED visits related to mental health problems grew from 6.5 to 8.1 percent; however, fewer than half of those patients (3.3 percent) had a primary diagnosis of mental illness (Larkin et al., 2004). It is estimated that more than 200,000 children present to the ED with mental health problems each year (Melesed’Hospital et al., 2002). The prevalence of impaired mental status among elderly patients is also high; studies indicate that 26 to 27 percent of patients aged 70 or older present to the ED with an impaired mental state (Hustey et al., 2001, 2003), and 10 percent suffer from delirium (Hustey and Meldon, 2002; Hustey et al., 2003). In a recent national survey, 70 percent of ED physicians reported an increase in patients with mental illness boarding in the ED. Most attribute this trend to cutbacks in state health care budgets and a decrease in the number of psychiatric beds (ACEP, 2004).

Some evidence suggests that the quality of care provided to these patients is substandard. Evidence indicates that mental illness often goes unrecognized and untreated in hospital EDs (Horowitz et al., 2001). One study reported a failure to document mental status for 56 percent of psychiatric patients admitted to one community hospital (Tintinalli et al., 1994). The authors suggested that the lack of documentation may be due to a tendency among ED staff to attribute psychiatric symptoms to physical problems. The inability or refusal of psychiatric patients to respond to a list of questions may also result in an incomplete evaluation (Tintinalli et al., 1994). A study of elderly ED patients with mental illness found that documentation of any mental impairment by the emergency physician was uncommon and that many elderly mentally impaired patients (including those with delirium) were discharged home without plans for addressing the impairment. The authors suggested that the lack of documentation and referrals indicates a lack of recognition of mental illness by emergency physicians (Hustey and Meldon, 2002). A third study found that emergency physicians failed to detect depression in most geriatric patients identified as depressed through a validated self-rated depression scale. As a result, few of those patients received a mental health or psychiatric referral (Meldon et al., 1997).

Studies have also pointed to shortcomings in the care of children with mental illness in the ED. A mid-1990s survey of hospitals revealed that formal mental health services for children are unavailable in most EDs (U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission, 1997). In a study of pediatric ED records from 10 hospitals, evaluation of pediatric patients with mental health problems appeared to be inconsistent with presenting classifications (Melese-d’Hospital et al., 2002). Three-fourths of emotionally disturbed children received an evaluation by a mental health professional at the ED, compared with 69 percent who had attempted suicide (Melese-d’Hospital

et al., 2002). Studies also indicate that proper management of adolescent suicide attempts in the ED is lacking. While the importance of follow-up psychiatric treatment has been demonstrated, psychotherapy is recommended for fewer than half of adolescent suicidal patients evaluated in the ED (Piacentini et al., 1995). Additionally, adolescents with somatic complaints are infrequently screened for depression (Porter et al., 1997).

Training and Capacity

ED providers often lack the training, skills, and resources to deal effectively with mentally ill patients. Standardized psychiatric training is not required of residents in emergency medicine and pediatric emergency medicine. Fewer than one-quarter of emergency medicine residency programs provide formal psychiatric training for residents (Santucci et al., 2003). Moreover, surveys of nurses—even those working in designated pediatric EDs—show that they are uncomfortable with pediatric psychiatric emergencies (Fredrickson et al., 1994). ED physicians also may not have the time to perform a thorough mental health evaluation, and many rely on psychiatrists, psychologists, or social workers to perform such an evaluation. When that assistance is not available, patients may not receive an evaluation at all. The ED setting also makes it difficult to care for a mentally ill patient. The lack of privacy and the noisy, high-stimulus environment may make it uncomfortable for patients to participate in a mental health evaluation (Hoyle and White, 2003).

Impact on the ED

Patients with mental illness have an important impact on EDs. They tend to require resource-intensive care, and their admission rates are high— 22 percent in one study (Larkin et al., 2004). These patients are also more likely to arrive by ambulance and to be classified as “urgent” than are ED patients who present without mental health problems (Larkin et al., 2004). Because hospital EDs often do not have specialized psychiatric facilities or psychiatric specialists available and find it difficult to place such patients—many of whom are indigent or uninsured—in outside facilities, ED staff spend more than twice as long seeking beds for these patients than for those without psychiatric problems. Psychiatric patients board in hospital EDs more than twice as long as other patients (ACEP, 2004).

According to the administrator of the Division of Mental Health and Developmental Services for the State of Nevada, the single overarching challenge facing the agency is the number of mentally ill patients who are crowding EDs in the southern part of the state. In 2004, the state had an

average of 42 patients waiting 61 hours in EDs for an inpatient mental health bed. More recently, the average was 62 patients waiting an average of 93 hours for an inpatient bed (Ryan, 2005). In a recent national survey, 6 in 10 emergency physicians said the increase in psychiatric patients seeking care at EDs is negatively affecting access to emergency care for all patients by generating longer waiting times and limiting the availability of ED staff and ED beds for other patients (ACEP, 2004).

Care for Substance Abuse

Data from the 2004 National Survey on Drug Use and Health indicate that 50 percent of the U.S. population aged 12 or older were current drinkers of alcohol in 2004; 23 percent were binge drinkers, meaning they had consumed five or more drinks on at least one occasion in the 30 days prior to the survey; and 7 percent were heavy drinkers, defined as binge drinking on 5 or more days in the past month. The survey data also indicate that 8 percent of the U.S. population over age 12 were illicit drug users in 2004 (SAMHSA, 2005).

Alcohol and other drug-related dependence is a pervasive problem in patients presenting to the ED. Between 1992 and 2000, approximately 8 percent of all ED visits each year were attributable to alcohol, and the total number of alcohol-related visits increased by 18 percent during that time (McDonald et al., 2004). Despite this statistic, a much higher percentage of patients would test positive for alcohol use if screened. One study found that one-third of adolescent patients tested as a part of routine care were alcohol-positive, but were not necessarily given an alcohol-related diagnosis (Barnett et al., 1998).

Estimates from the Drug Abuse Warning Network, a surveillance system operated by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) that collects data on drug-related ED visits (including those involving alcohol) across the country, indicate that there were approximately 628,000 drug-related ED visits in the United States in the second half of 2003. Of those visits, 33 percent were for an adverse reaction, 17 percent for overmedication, 10 percent for detoxification, and 6 percent for drug-related suicide attempts (SAMHSA, 2005). Among drug-related visits in 2002, 80 percent involved only seven categories: alcohol in combination with another drug (31 percent); cocaine (30 percent); marijuana (18 percent); heroin (14 percent); and benzodiazepines, antidepressants, and analgesics, which together accounted for 30 percent of such visits (SAMHSA, 2004).

Again, however, many more patients would likely test positive for drug use if screened. In a study of alcohol and drug use in seven Tennessee general

hospital EDs, marijuana was identified in 15 percent of all patients willing and able to participate in a drug screen, benzodiazepines in 11 percent, opioids in 9 percent, and stimulants in 6 percent (Rockett et al., 2003).

Patients often present to the ED with acute or chronic manifestations of alcohol or drug problems. Chronic problems related to alcohol and other drug use include skin infections from drug injections, cirrhosis and its complications, and gastrointestinal disorders. Alcohol and other drug use often occurs in the presence of, or may lead to, physical illness and injury. Among patients that present to the ED with injuries, those that report alcohol or drug use are significantly more likely to report violence associated with the episode (Cunningham et al., 2003). Drug abuse can complicate the evaluation of the injured patient by masking signs and symptoms of injury (Fabbri et al., 2001). Conversely, ED staff may focus on the patient’s injury and neglect to screen for drug abuse.

Screening and on-site interventions and referrals for alcohol have been demonstrated in a variety of health care settings, including the ED, to reduce ED and hospital use and decrease the amount that patients drink (Bernstein et al., 1997; Wright et al., 1998; Monti et al., 1999; Helmkamp et al., 2003). In one study of 700 trauma patients admitted for alcohol-related injuries, those that received 30 minutes of counseling at the hospital experienced a 47 percent reduction in serious injuries requiring trauma center admission in the following 3 years and a 48 percent reduction in less serious injuries requiring ED care (Gentilello et al., 1999). A recent meta-analysis of screening and brief intervention identified 39 published studies, 30 of which found a positive effect (D’Onofrio and Degutis, 2002). Additionally, studies have shown that ED patients are often accepting of screening and brief interventions for alcohol problems (Cherpitel et al., 1996; Leikin et al., 2001).

However, research has shown that ED physicians usually fail to identify those at risk for problems with alcohol or to provide such interventions (Gentilello et al., 1999; O’Rourke et al., 2001; Manley et al., 2002). Similar studies have found a high prevalence of undetected substance abuse and an unmet need for treatment among ED patients (Bernstein et al., 1999; Rockett et al., 2003). This situation has been demonstrated by a number of studies even though numerous federal and expert panels have recommended routine screening of injured patients in the ED for substance abuse and the provision of brief interventions for those that test positive (Gentilello, 2003). According to a survey sponsored by the West Virginia Chapter of the American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP), barriers to screening include provider attitudes of disinterest, avoidance, disdain, and pessimism, as well as inadequate time, insufficient education, and a lack of resources. The survey found that a minority of ED physicians routinely screen and council ED patients on alcohol abuse (Williams et al., 2000).

Reimbursement

Another important barrier to screening of patients for alcohol or drug abuse by ED staff is that the care provided may not be reimbursed if the screen is positive. In some states, laws permit insurance companies to refuse payment for injuries sustained if the patient is found to be under the influence of alcohol or drugs. The intent of these laws is to punish drunk drivers, thereby reducing the cost of insurance for others (Gentilello, 2003). However, physicians may be reluctant to screen patients for alcohol or drugs because of the potential financial impact on patients, the hospital, and themselves.

Impact on the ED

Like mental health patients, those with identified substance-abuse problems tend to be a resource-intensive group. In a statewide study, ED patients with unmet substance-abuse treatment needs generated much higher hospital and ED charges than other patients (Rockett et al., 2005). Yet treatment for addiction requires continuing care, adherence to medications, and behavioral change (D’Onofrio, 2003), none of which are likely to be accomplished during the course of an ED visit. The ED does, however, offer an opportunity to identify, intervene with, and refer patients who have substance-abuse problems (D’Onofrio et al., 1998; Rockett et al., 2003).

Not only do substance-abuse patients require extra time and effort on the part of ED staff, but drug-related ED visits have become a major cause of violence in the ED (Anonymous, 1990). For example, a patient who is primarily seeking drugs may turn violent if not able to obtain them (van Steenburgh, 2002). The types of patient presentations most associated with violence are intoxicant use, states of withdrawal from drugs, delirium, head injury, psychiatric problems, and social factors (Lavoie et al., 1988).

RURAL EMERGENCY CARE

According to the U.S. Census Bureau (2000), more than 59 million people, or 21 percent of the total U.S. population, reside in rural areas. Rural EDs face a number of problems that differ from those of urban hospitals, including limited availability of hospitals and equipment, an inadequate supply of qualified staff, an unfavorable payer mix, and long distances and emergency response times. A recent IOM study, Quality through Collaboration: The Future of Rural Health, documented the difficulties faced by rural communities in providing high-quality medical services, particularly emergency care (IOM, 2004).

Availability of Hospitals and Equipment

There are nearly 2,200 rural community hospitals in the United States, representing 44 percent of all community hospitals (AHA, 2005a). Between 1980 and 2002, more than 400 rural hospitals closed. Rural hospitals are smaller than their urban counterparts, with a median of 58 beds compared with 186 for urban hospitals (The Lewin Group, 2002). Smaller hospitals tend to have lower margins than larger ones; more than 50 percent of hospitals with fewer than 25 beds have negative margins, versus only 13 percent of those with 200 or more (The Lewin Group and AHA, 2000). The modest size of rural hospitals and their correspondingly small capital and financial assets make them less able to survive significant changes in financial performance; when the financial survival of a hospital is at stake, investments in the latest technologies and recruitment of highly qualified personnel are assigned low priority.

Given the high cost of maintaining trauma centers and the difficulty of maintaining them even in busy urban areas (Taheri et al., 2004), it is unrealistic to expect that each rural ED will have the full spectrum of trauma resources available. When caring for a traumatized patient, the rural emergency physician’s focus is primarily on rapid patient assessment, stabilization, and transfer. Rural EDs also lack many of the newer diagnostic modalities. Such shortages impair the establishment of definitive diagnoses, as well as the application of the latest potential improvements in emergency practice. For example, acute stroke treatment with tissue plasminogen activator (TPA) requires immediate access to a computed tomography (CT) scanner and a fast accurate reading, neither of which may be available at most rural EDs (Drummond, 1998).

Payer Mix

The population served by rural hospitals tends to be poorer, to be uninsured, and to make greater use of various forms of public health insurance. While 72 percent of urban residents had private insurance coverage in 1998, this was the case for only 60 percent of those living in remote rural areas. Rural workers tend to be self-employed, to work for smaller companies, and to earn lower wages. These factors compromise access to private health insurance. The impingement of private health insurance and managed care, public and private, is a major factor determining the financial environment in which rural hospitals are situated (Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, 2003).

In 2001, over 7 million people living in rural areas were uninsured, including 24 percent of those living in remote rural areas, defined as rural counties nonadjacent to a county with an urban center. This high level of uninsured is compounded by the fact that the rural uninsured tend to lack

insurance for longer periods of time than their urban counterparts. They are also older, and their self-reported health is poorer. One-quarter of rural uninsured are aged 45–64, and 42 percent of rural uninsured residents report less than very good health, compared with 38 percent of urban uninsured residents (Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, 2003). The large numbers of uninsured in rural areas can have spillover effects on the community, reducing access to emergency services, trauma care, specialists, and hospital-based services (Kellermann and Snyder, 2004). Unreimbursed care for emergency physicians and hospitals can result in cutbacks, closure, or relocation of services (Irvin et al., 2003a).

The low levels of private insurance and low incomes in rural America contribute to the important role played by Medicaid and other forms of public insurance in these areas. Public programs insure 16 percent of those in rural areas, compared with 10 percent in urban settings. Therefore, rural hospitals are much more dependent on these programs for their existence. The Balanced Budget Act (BBA) of 1997 and the Balanced Budget Refinement Act (BBRA) of 1999 have had a significant impact on the access to emergency care in rural environments. The BBA mandated that Medicare outpatient payments become prospective, saving $110 billion from 1998 to 2004. Medicare payment reductions to rural hospitals were projected to have a cumulative impact of $16.7 billion over this time frame (IOM, 2000). The BBRA preferentially reinstated cost-based reimbursement to rural hospitals for some services and included higher payments to Medicare-dependent hospitals. The restoration of these payments is expected to reduce the cumulative impact of the BBA by $1.8 billion to approximately $15 billion overall. Yet the impact on rural hospitals remains tremendous, as these acts have projected Medicare margins in rural hospitals to decrease by 3.3–8.4 percent by 2004. Particularly hard hit are outpatient services, expected to decrease by 20–28 percent (IOM, 2000). Given the marginal financial existence of many rural hospitals, these reductions may have detrimental effects on hospitals’ survival and provision of services, including outpatient ED services, and may even precipitate closure.

To increase the access of rural residents to urgent and emergency services, Congress established the Critical Access Hospital (CAH) program as part of the BBA. A CAH is exempt from the prospective payment system for both inpatient and outpatient care. Instead, hospitals that receive this designation bill Medicare on a fee-for-service basis. Medicare reimburses at a rate of 100–101 percent of reasonable and customary charges. CAHs are specially designated under the Medicare Rural Hospital Flexibility Grant Program. These rural, low-volume hospitals must meet distinct criteria regarding location, number of available beds, and average length of stay, or may be state certified as a “necessary provider.” Emergency services must also be available 24 hours daily. A hospital can be designated as a CAH