3

Building a 21st-Century Emergency Care System

Hospitals are part of a continuum of emergency care services that includes 9-1-1 and ambulance dispatch, prehospital emergency medical services (EMS) care and transport, hospital-based emergency and trauma care, and inpatient services. While today’s emergency care system offers significantly more medical capability than was available in years past, it continues to suffer from severe fragmentation, an absence of systemwide coordination, and a lack of accountability. These shortcomings diminish the care provided to emergency patients and often result in worsened medical outcomes. To address these challenges and chart a new direction for emergency care, the committee envisions a system in which all communities will be served by well-planned and highly coordinated emergency care services that are accountable for performance and serve the needs of patients of all ages within the system.

In this new system, 9-1-1 dispatchers, EMS personnel, medical providers, public safety officers, and public health officials will be fully interconnected and united in an effort to ensure that each patient receives the most appropriate care, at the optimal location, with the minimum delay. From the patient’s point of view, delivery of services for every type of emergency will be seamless. All service delivery will also be evidence based, and innovations will be rapidly adopted and adapted to each community’s needs. Hospital emergency department (ED) closures and ambulance diversions will never occur, except in the most extreme situations, such as a hospital fire or a communitywide mass casualty event. Standby capacity appropriate to each community based on its disaster risks will be embedded in the system. The performance of the system will be transparent, and the public will be

actively engaged in its operation through prevention, bystander training, and monitoring of system performance.

While these objectives will require substantial, systemwide change, they are achievable. Early progress toward the goal of more integrated, coordinated, regionalized emergency care systems became derailed over the last two decades. Efforts stalled because of deeply entrenched interests and cultural attitudes, as well as funding cutbacks and practical impediments to change. These obstacles remain today, and represent the primary challenges to achieving the committee’s vision. However, the need for change is clear. The committee calls for concerted, cooperative efforts at multiple levels of government and the private sector to finally achieve the objectives outlined above.

This chapter describes the committee’s vision for a 21st-century emergency care system. This vision rests on the broad goals of improved coordination, expanded regionalization, and increased transparency and accountability, each of which is discussed in turn. Next, current approaches of states and local regions that exhibit these features are profiled. The chapter then details the committee’s recommendation for a federal demonstration program to support additional state and local efforts aimed at attaining the vision of a more coordinated and effective emergency care system. The chapter ends with a discussion of the need for system integration and a presentation of the committee’s recommendation regarding a federal lead agency to meet that need.

THE GOAL OF COORDINATION

The value of integrating and coordinating emergency care has long been recognized. The 1996 National Academy of Sciences/National Research Council (NAS/NRC) report Accidental Death and Disability called for better coordination of emergency care through Community Councils on Emergency Medical Services that would bring together physicians, medical facilities, EMS, public health agencies, and others “to procure equipment, construct facilities and ensure optimal emergency care on a day-to-day basis as well as in a disaster or national emergency” (NAS and NRC, 1966, p. 7). The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration’s (NHTSA) 1996 report Emergency Medical Services Agenda for the Future also emphasized the goal of system integration:

EMS of the future will be community-based health management that is fully integrated with the overall health care system. It will have the ability to identify and modify illness and injury risks, provide acute illness and injury care and follow-up, and contribute to treatment of chronic conditions and community health monitoring…. [P]atients are assured that their care is considered part

of a complete health care program, connected to sources for continuous and/or follow-up care, and linked to potentially beneficial health resources…. EMS maintains liaisons, including systems for communication with other community resources, such as other public safety agencies, departments of public health, social service agencies and organizations, health care provider networks, community health educators, and others…. EMS is a community resource, able to initiate important follow-up care for patients, whether or not they are transported to a health care facility. (NHTSA, 1996, Pp. 7, 10)

In 1972, the NAS/NRC report Roles and Responsibilities of Federal Agencies in Support of Comprehensive Emergency Medical Services promoted an integrated, systems approach to planning at the state, regional, and local levels and called for the Department of Health, Education and Welfare (DHEW) to take an administrative and leadership role in federal EMS activities. The Emergency Medical Services Systems Act of 1973 (P.L. 93-154) created a new grant program in DHEW’s Division of EMS to foster the development of regional EMS systems. The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation added support by funding the development of 44 regional EMS systems. Although the drive toward system development waned after the demise of the DHEW program and the subsequent absorption of federal EMS funding into federal block grants in 1981, the goals of system planning and coordination remained paramount within the emergency care community.

Limited Progress

While the concept of a highly integrated emergency care system as articulated in NHTSA’s Emergency Medical Services Agenda for the Future is not new, progress toward its realization has been slow. Prehospital EMS, hospital-based emergency and trauma care, and public health have traditionally worked in silos (NHTSA, 1996), a situation that largely persists today. For example, public safety and EMS agencies often lack common communications frequencies and protocols for communicating with each other during emergencies. Jurisdictional borders contribute to fragmentation under the current system. For example, one county in Michigan has 18 different EMS systems with a range of different service models and protocols. Coordination of services across state lines is particularly challenging.

Trauma systems provide a valuable model for how such coordination could and should operate. The inclusive trauma system is meant to ensure that each patient is directed to the most appropriate setting, including a level I trauma center, when necessary. To this end, many elements within the regional system—community hospitals, trauma centers, and particularly prehospital EMS—must coordinate the regional flow of patients effectively. Such coordination not only improves patient care, but also is a critical tool in reducing overcrowding in EDs.

Unfortunately, only a handful of systems nationwide coordinate transport effectively throughout the region. Short of formally going on diversion, there is typically little information sharing between hospitals and EMS regarding overloaded emergency and trauma centers and availability of ED beds, operating suites, equipment, trauma surgeons, and critical specialists—information that could be used to balance the load among EDs and trauma centers in the region. Too often hospitals are located such that one is overloaded with emergency and trauma patients, while just several blocks away another works at a comfortable 50 percent of capacity. There is little incentive for ambulances to drive by a hospital to take patients to a facility that is less overloaded.

The benefits to patients of better regional coordination have been demonstrated. Furthermore, the technologies needed to facilitate such approaches exist; police and fire departments are ahead of the emergency care system in this regard. The main impediment appears to be entrenched interests and a lack of sufficient vision to change the current system.

The problem is intensified in some regions by turf wars between fire-fighters and EMS personnel that were documented in a series of articles for USA Today (Davis, 2003). Moreover, air medical services typically operate outside the control of the EMS system and have a poor record of safety and effectiveness in transporting patients. The situation is exacerbated in cities with both private and public EMS agencies that sometimes compete for patients and transport based on hospital ownership of the agency rather than what is best for the patient. Even within EDs, there may be friction between emergency staff trying to admit patients and personnel on inpatient units who have no incentive to speed up the admissions process. Lack of coordination between EMS and hospitals can result in delays that compromise care, and emergency physicians sometimes clash with on-call specialists and admitting physicians over delays in response.

Linkages with Public Health

The ED has a special relationship with the community and state and local public health departments because it serves as a community barometer of both illness and injury trends (Malone, 1995). In her analysis of heavy users of ED services, Malone argued that “emergency departments remain today a ‘window’ on wider social issues critical to health care reforms” (Malone, 1995, p. 469). A commonly cited example is the use of seat belts. We now know that increased use of seat belts reduces the number of seriously injured car crash victims in the ED—the ED served as a proving ground for documenting the results of seat belt enforcement initiatives. Although prevention activities have been limited in the emergency care setting, that

setting represents an important teaching opportunity. To take advantage of that opportunity, emergency care providers would benefit from the resources and experiences of public health agencies and experts in the implementation of injury prevention measures.

Perhaps now more than ever, with the threat of bioterrorism and outbreaks of such diseases as avian influenza and severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), it is essential that EMS, EDs, trauma centers, and state and local public health agencies partner to conduct surveillance for disease prevalence and outbreaks and other health risks. Hospital EDs can recognize the diagnostic clues that may indicate an unusual infectious disease outbreak so that public health authorities can respond quickly (GAO, 2003c). However, a solid partnership must first be in place—one that allows for easy communication of information between emergency providers and public health officials.

Linkages with Other Medical Care Providers

As discussed earlier, EDs fill a variety of gaps within the health care network and serve as key safety net providers in many communities (Lewin and Altman, 2000). Studies have shown that a significant number of patients use the ED for nonurgent purposes because of financial barriers, lack of access to clinics after hours, transportation barriers, convenience, and lack of a usual source of care (Grumbach et al., 1993; Young et al., 1996; Peterson et al., 1998; Koziol-McLain et al., 2000; Cunningham and May, 2003) (see Chapter 2). There is also evidence that clinics and physicians are increasingly using EDs as an adjunct to their practice, referring patients to the ED for a variety of reasons, such as their own convenience after regular hours, reluctance to take on a complicated case, the need for diagnostic tests they cannot perform in the office, and liability concerns (Berenson et al., 2003; Studdert et al., 2005). (See the detailed discussion of these issues in Chapter 2.) Unfortunately, in many communities there is little interaction between emergency care services and community safety net providers—this even though they share a common base of patients, and their actions may affect one another substantially. The absence of coordination represents missed opportunities for enhanced access; improved diagnosis, patient follow-up, and adherence to treatment; and enhanced quality of care and patient satisfaction.

Successes Achieved

While progress toward a highly integrated emergency care system has been slow, some important successes in the coordination of emergency

care services point the way toward solutions to the fragmentation that dominates the system today. For example, the trauma system in Maryland, described in more detail later in this chapter, provides a comprehensive and coordinated approach to the care of injured children. Children’s hospitals have also been successful in accomplishing regional coordination to ensure the transport and appropriate care of children needing specialized services. The pediatric intensive care system is a leading example of regional coordination among hospitals, community physicians, and emergency medical technicians (EMTs) (Gausche-Hill and Wiebe, 2001). These are but a few examples demonstrating the possibilities for enhancing coordination of the system as a whole.

One promising public health surveillance effort is Insight, a computer-based clinical information system at the Washington Hospital Center (WHC) in Washington, D.C., designed to record and track patient data, including geographic and demographic information. The software proved useful during the 2001 anthrax attacks, when it enabled WHC to transmit complete, real-time data to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) while other hospitals were sending limited information with a lag time of one or more days. The success of Insight attracted considerable grant funding for the system’s expansion; WHC earmarked $7 million for the system to link it to federal and regional agencies and to integrate it with other hospital systems (Kanter and Heskett, 2002).

Many communities have established primary care networks that integrate hospital EDs into their planning and coordination efforts. A rapidly growing number of communities, such as San Francisco and Boston, have developed regional health information organizations that coordinate the development of information systems to facilitate patient referrals and track the sharing of medical information between providers to optimize a patient’s care across settings. The San Francisco Community Clinic Consortium brings together primary and specialty care providers and EDs in a planning and communications network that closely coordinates the care of safety net patients throughout the city.

The Importance of Communications

Communications are a critical factor in establishing systemwide coordination. An effective communications system is the glue that can hold together effective, integrated emergency care services. It provides the key link between 9-1-1/dispatch and EMS responders and is necessary to ensure that on-line medical direction is available when needed. It enables ambulance dispatchers to tell callers what to do until help arrives and to track a patient’s progress following the arrival of EMS responders. An effective communications system also enables ambulance dispatchers to assist EMS

personnel in directing patients to the most appropriate facility based on the nature of their illness or injury and the capacity of receiving facilities. It links the emergency medical system with other public safety providers—such as police and fire departments, emergency management services, and public health agencies—and facilitates coordination between the medical response system and incident command in both routine and disaster situations. It helps hospitals communicate with each other to organize interfacility transfers and arrange for mutual aid. And it facilitates medical and operational oversight and quality control within the system.

THE GOAL OF REGIONALIZATION

The objective of regionalization is to improve patient outcomes by directing patients to facilities with optimal capabilities for any given type of illness or injury. Substantial evidence demonstrates that doing so improves outcomes and reduces costs across a range of high-risk conditions and procedures, including cardiac arrest and stroke (Grumbach et al., 1995; Imperato et al., 1996; Nallamothu et al., 2001; Chang and Klitzner, 2002; Bardach et al., 2004). The literature also supports the benefits of regionalization for severely injured patients in improving patient outcomes and lowering costs (Jurkovich and Mock, 1999; Mann et al., 1999; Mullins and Mann, 1999; Chiara and Cimbanassi, 2003; Bravata et al., 2004; MacKenzie et al., 2006), although the evidence in this regard is not uniformly positive (Glance et al., 2004). MacKenzie and colleagues (2006) have provided the strongest evidence to date for the benefits of such regionalized trauma systems. In their study, mortality among patients receiving trauma center and comparable non–trauma center care in 14 states was compared after adjustment for differences in case mix. Mortality among patients with serious injuries was significantly lower at trauma centers. Other studies have likewise documented the value of regionalized trauma systems in improving outcomes and reducing mortality from traumatic injury (Jurkovich and Mock, 1999; MacKenzie, 1999; Mullins, 1999; Nathens et al., 2000). Organized trauma systems have also been shown to add value in facilitating performance measurement and promoting research. Formal protocols within a region for prehospital and hospital care contribute to improved patient outcomes as well (Bravata et al., 2004).

While regionalization to distribute trauma services to high-volume centers is optimal when feasible in terms of transport, Nathens and Maier (2001) argued for an inclusive trauma system in which smaller facilities have been verified and designated as lower-level trauma centers. They suggested that care may be substantially better in such facilities than in those outside the system, and comparable to national norms (Nathens and Maier, 2001). An inclusive trauma system addresses the needs of all injured patients across

the entire continuum of care and utilizes the resources of all committed and qualified personnel and facilities, with the goal of ensuring that every injured patient is triaged expeditiously to a level of care commensurate with his or her injuries.

Research has demonstrated a number of additional benefits of regionalization. Regionalizing inventories (pooling supplies at regional warehouses) has been shown to reduce inventories, improve the capacity to serve the target population, and save money. Regionalization may also be a cost-effective strategy for developing and training teams of response personnel. Regionalization benefits outbreak investigations, security management, and emergency management as well. Both the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) and CDC have made regional planning a condition for preparedness funding (GAO, 2003a).

Concerns About Regionalization

Not all aspects of regionalization are positive. If not properly implemented, regionalizing key clinical services may adversely impact their overall availability in a community. For example, regional allocation of patients with suspected acute myocardial infarction could result in the closure of a cardiac unit or even an entire hospital, particularly in rural areas. The survival of small rural facilities may require identification and treatment of those illnesses and injuries that do not require the capacities and capabilities of larger facilities, as well as repatriation to the local facility for long-term care and follow-up after stabilization at the tertiary center. A systems approach to regionalization considers the full effects of regionalizing services on a community. Determining the appropriate metrics for this type of analysis and defining the process for applying them within each region are significant research and practical issues. Nonetheless, in the absence of rigorous evidence to guide the process, planning authorities should take these factors into account in developing regionalized systems of emergency care.

The committee believes communities will best be served by emergency care systems in which services are organized so as to provide the optimal care based on the patient’s location and condition. To the extent that the movement toward specialty hospitals impacts the configuration of services and therefore the ability of the system to optimize emergency services, it is an appropriate subject for the committee to address. While the committee does not advocate for or against the further development of specialty hospitals, it does believe that their development would potentially impact emergency care and that this impact, which in some cases could be adverse, should be considered in the regionalization of emergency care. Specialty hospitals that do not provide emergency care can drain financial resources from those that do (GAO, 2003b; Dummit, 2005). Also, specialty hospitals present an

attractive option for some specialists, potentially luring them away from the medical staffs of general hospitals. In such cases, general hospitals may be forced to subsidize specialists, or recruit new ones, to remain compliant with the Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act (EMTALA) (Asplin and Knopp, 2001; Iglehart, 2005; Johnson et al., 2001). Specialty hospitals may also siphon commercially insured patients away from general hospitals while retaining the option of sending their sickest patients to the nearest general hospital ED.

Despite these problems, the movement toward specialty hospitals is gathering strength. The number of ambulatory surgery centers increased by about 6 percent per year between 1997 and 2003, to a total of 3,735 recorded nationally in 2003; the number of specialty hospitals increased by approximately 20 percent per year between 1997 and 2003, to a total of 113 in 2003 (Iglehart, 2005). In December 2003, Congress declared an 18-month moratorium on the development of new specialty hospitals partly owned by physicians who refer their patients to those facilities. Federal agencies were directed to study these facilities and recommend an extension of the moratorium or a new policy. The moratorium expired in 2005, but the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) is studying how to revise its payment rates and procedures for approving specialty hospitals.

Configuration of Services

The design of the emergency care system envisioned by the committee bears similarities to the inclusive trauma system concept originally conceived and first proposed and developed by CDC, and adapted and disseminated by the American College of Surgeons. Under this approach, every hospital in the community can play a role in the trauma system by undergoing verification and designation as a level I to level IV/V trauma center, based on its capabilities. Trauma care is optimized in the region through protocols and transfer agreements that are designed to direct trauma patients to the most appropriate level of care available given the type of injury and relative travel times to each center.

The committee’s vision expands this concept beyond trauma care to include all serious illnesses and injuries, and extends beyond hospitals to include the entire continuum of emergency care—including 9-1-1 and dispatch and prehospital EMS, as well as clinics and urgent care providers. In this model, every provider organization can potentially play a role in providing emergency care services according to its capabilities. Provider organizations undergo a process by which their capabilities are identified and categorized in a manner not unlike trauma verification and designation, which results in a complete inventory of emergency care provider organizations within a community. Initially, this categorization may simply be based on the ex-

istence of a service—for example, capacity to achieve cardiac reperfusion or perform emergency neurosurgery. Over time, the categorization process may evolve to include more detailed information, such as the times specific emergency procedures are available; the arrangements for on-call specialty care; service-specific outcomes; or general emergency service indicators, such as time to treatment, frequency of diversion, and ED boarding. Prehospital EMS services are similarly categorized according to ambulance capacity; availability; credentials of EMS providers; advanced life support (ALS) and pediatric advanced life support (PALS); treat and release and search and rescue capabilities; disaster readiness (e.g., extrication capability and personal protective equipment); and outcomes for sentinel indicators, such as out-of-hospital cardiac arrest.

A standard national approach to the categorization of emergency care providers is needed. Categories should reflect meaningful differences in the types of emergency care available, yet be simple enough to be understood easily by emergency care organizations and the public at large. The use of national definitions would ensure that the categories would be understood by providers and by the public across states or regions of the country, and would also promote benchmarking of performance.

The committee concludes that a standard national approach to the categorization of emergency care, defined in the broadest possible sense, is essential for the optimal allocation of resources and provision of critical information to an informed public. Therefore the committee recommends that the Department of Health and Human Services and the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, in partnership with professional organizations, convene a panel of individuals with multidisciplinary expertise to develop evidence-based categorization systems for emergency medical services, emergency departments, and trauma centers based on adult and pediatric service capabilities (3.1). The results of this process would be a complete inventory of emergency care assets for each community, which should be updated regularly to reflect the rapid changes in delivery systems nationwide. The development of the initial categorization system should be completed within 18 months of the release of this report.

Treatment, Triage, and Transport

Once the basic classification system proposed above is understood, it can be used to determine the optimal destination for patients based on their condition and location. However, more research and discussion are needed to determine the circumstances under which patients should be brought to the closest hospital for stabilization and transfer as opposed to being transported directly to the facility offering the highest level of care, even if that facility is farther away. A debate remains over whether EMS providers

should perform ALS procedures in the field, or rapid transport to definitive care is best (Wright and Klein, 2001). It is likely that this answer depends, at least in part, on the type of emergency condition. It is evident, for example, that whether a patient will survive out-of-hospital cardiac arrest depends almost entirely on actions taken at the scene, including rapid defibrillation, provision of cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), and perhaps other ALS interventions. Delaying these actions until the unit reaches a hospital results in dismal rates of survival and poor neurological outcomes. Conversely, there is little that prehospital personnel can do to stop internal bleeding from major trauma. In this instance, rapid transport to definitive care in an operating room offers the victim the best odds of survival. For example, a recent study showed that bypassing a level II trauma center in favor of a more distant level I trauma center may be optimal for head trauma patients (McConnell et al., 2005).

EMS responders who provide stabilization before the patient arrives at a critical care unit are sometimes subject to criticism because of a strongly held bias among many physicians that out-of-hospital stabilization only delays definitive treatment without adding value; however, there is little evidence that the prevailing “scoop and run” paradigm of EMS is always optimal (Orr et al., 2006). For example, in cases of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest, properly trained and equipped EMS personnel can provide all needed interventions at the scene. In fact, research has shown that failure to reestablish a pulse on the scene virtually ensures that the patient will not survive, regardless of what is done at the hospital (Kellermann et al., 1993). On the other hand, a scoop and run approach makes sense when a critical intervention needed by the patient can be provided only at the hospital (for example, surgery to control internal bleeding).

Decisions regarding the appropriate steps to take should be resolved using the best available evidence. The committee concludes that there should be a national approach to the development of prehospital protocols. It therefore recommends that the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, in partnership with professional organizations, convene a panel of individuals with multidisciplinary expertise to develop evidence-based model prehospital care protocols for the treatment, triage, and transport of patients (3.2). The transport protocols should also reflect the state of readiness of given facilities within a region at a particular point in time. Real-time, concurrent information on the availability of hospital resources and specialists should be made available to EMS providers to support transport decisions. Development of an initial set of model protocols should be completed within 18 months of the release of this report. Treatments may require modification to reflect local resources, capabilities, and transport times; however, the basic pathophysiology of human illness is the same in all areas of the country. Once in place, the national protocols could be

tailored to local assets and needs. The process for updating the protocols will also be important because it will dictate how rapidly patients receive the current standard of care.

The 1966 report Accidental Death and Disability anticipated the need to categorize care facilities and improve transport decisions:

The patient must be transported to the emergency department best prepared for his particular problem…. Hospital emergency departments should be surveyed …to determine the numbers and types of emergency facilities necessary to provide optimal emergency treatment for the occupants of each region…. Once the required numbers and types of treatment facilities have been determined, it may be necessary to lessen the requirements at some institutions, increase them in others, and even redistribute resources to support space, equipment, and personnel in the major emergency facilities. Until patient, ambulance driver, and hospital staff are in accord as to what the patient might reasonably expect and what the staff of an emergency facility can logically be expected to administer, and until effective transportation and adequate communication are provided to deliver casualties to proper facilities, our present levels of knowledge cannot be applied to optimal care and little reduction in mortality and/or lasting disability can be expected. (NAS and NRC, 1966, P. 20)

This concept was echoed in the 1993 Institute of Medicine (IOM) report Emergency Medical Services for Children, which stated that “categorization and regionalization are essential for full and effective operation of systems” (IOM, 1993, p. 171).

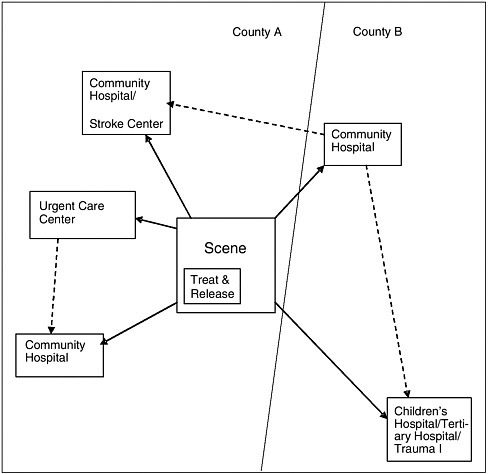

Once the decision has been made to transport a patient, the responding ambulance unit should be instructed—either by written protocol or by on-line medical direction—which hospital should receive the patient. This instruction should be based on developed transport protocols to ensure that the patient is taken to the optimal facility given the severity and nature of the illness or injury, the status of the various care facilities, and the travel times involved. Ideally, this decision will take into account a number of complex and fluctuating factors, such as hospital ED closures and diversions and traffic congestion that hinders transport times for the EMS unit (The SAFECOM Project, 2004). Some potential transport options in a coordinated, regionalized system are depicted in Figure 3-1.

In addition to the use of ambulance units and the EMS system to direct patients to the optimum location for emergency care, hospital emergency care designations should be posted prominently to improve patients’ self-triage decisions. Such postings can educate the public about the types of emergency services available in their community and enable patients who are not using EMS to direct themselves to the optimal facility.

FIGURE 3-1 Potential transport options within a coordinated, regionalized system. The basic structure of current EMS systems is not altered, but protocols are refined to ensure that patients go to the optimal facility given the type of illness or injury, the travel time involved, and facility status (e.g., ED and intensive care unit [ICU] bed availability). For example, instead of taking a stroke victim to the closest general community hospital or to a tertiary medical center that is farther away, there may be a third option—transport to a community hospital with a stroke center. Over time, based on evidence on the effectiveness of alternative delivery models, some patients may be transported to a nearby urgent care center for stabilization or treated on the street and released. Whichever pathway the patient follows, communications are enhanced, data are collected, and the performance of the system is evaluated and reported so that future improvements can be made.

THE GOAL OF ACCOUNTABILITY

Accountability is perhaps the most important of the three goals of the emergency care system envisioned by the committee because it is necessary to achieving the other two. Lack of accountability has contributed to the failure of the emergency care system to adopt needed changes in the past. Without accountability, participants in the system need not accept responsibility for failure and can avoid making changes necessary to avoid the same outcomes in the future.

Accountability is difficult to establish in emergency care because responsibility is dispersed across many different components of the system; thus it is difficult for policy makers to determine when and where breakdowns occur and how they can be prevented in the future. Ambulance diversion is a good example. Because diversion statistics are rarely published or announced, the problem is likely to remain outside the public eye. When a city finally recognizes it has an unacceptably high frequency of diversion, whom should it hold accountable? EMS can blame the hospitals for crowded conditions and excessively long offload times; hospitals can blame the on-call specialists or the discharge sites that are unwilling to take additional referrals; and everyone can blame the public health department for inadequate funding of community-based clinics.

The unpredictable and infrequent nature of emergency care contributes to the lack of accountability. Most people have limited exposure to the emergency care system—for most Americans, an ambulance call or a visit to the ED is a relatively rare event. Further, public awareness is hindered by the lack of nationally defined indicators of system performance. Few localities can answer basic questions about their emergency care services, such as “What is the overall performance of the emergency care system?”; “How well do 9-1-1, ambulance services, hospital emergency and trauma care, and other components of the system perform?”; and “How does performance compare with that in other parts of the state and the country?” Consequently, few understand the crisis presently facing the system. By and large, the public assumes that the system functions better than it does (Harris Interactive, 2004).

The committee believes several steps are required to bring accountability to the emergency care system. These include the development of national performance indicators, implementation of performance measurement, and public dissemination of performance information.

Development of National Performance Indicators

There is currently no shortage of performance measurement and standards-setting projects. For example, ED performance measures have

been developed by Qualis Health and Lindsay (Lindsay et al., 2002). In addition, the Data Elements for Emergency Department Systems (DEEDS) project and Health Level Seven (HL7) are working to develop uniform specifications for ED performance data (Pollock et al., 1998; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and National Center for Injury Control and Prevention, 2001).

The EMS Performance Measures Project is working to develop consensus measures of EMS system performance that will assist in demonstrating the system’s value and defining an adequate level of EMS service and preparedness for a given community (measureEMS.org, 2005). The consensus process of the project has sought to unify disparate efforts to measure performance previously undertaken nationwide that have lacked consistency in definitions, indicators, and data sources. In 2004, the project developed 138 indicators of EMS performance, which were pared down to 25 indicators in 2005. The list included system measures, such as “What are the time intervals in a call?” and “What percentage of transports is conducted with red lights and sirens?”, and clinical measures, such as “How well was my pain relieved?” The questions were defined using data elements from the National EMS Information System (NEMSIS) dataset so that results could be compared with validity across EMS systems. The EMS Performance Measures Project is coordinated by the National Association of State EMS Officials in partnership with the National Association of EMS Physicians and is supported by NHTSA and HRSA. CDC, the Association of American Medical Colleges, and Emory University are currently developing a simple cardiac arrest registry that will allow communities across the United States to determine their rate of successful resuscitations and identify opportunities for improvement.

In addition, statewide trauma systems and EMS systems have been evaluated by the American College of Surgeons’ Committee on Trauma; NHTSA’s Office of EMS; and, until it was recently defunded, HRSA’s Division of Trauma and EMS Systems. There are also various components of the system with independent accrediting bodies. Hospitals, for example, are accredited by the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO); ambulance services are accredited by the Commission on Accreditation of Ambulance Services; and air medical services are voluntarily accredited by the Commission on Accreditation of Medical Transport Systems. Each of these organizations collects performance information.

What is missing is a standard set of measures that can be used to assess the performance of the full emergency care system within each community, as well as the ability to benchmark that performance against statewide and national performance metrics. A credible entity to develop such measures would not be strongly tied to any one component of the emergency care continuum.

One approach would be to form a collaborative entity that would include representation from all of the system components, including hospitals, trauma centers, EMS agencies, physicians, nurses, and others. Another approach would be to work with an existing organization, such as the National Quality Forum (NQF), to develop a set of emergency care–specific measures. NQF grew out of the President’s Advisory Commission on Consumer Protection and Quality in the Health Care Industry in 1998. It operates as a not-for-profit membership organization made up of national, state, regional, and local groups representing consumers, public and private purchasers, employers, health care professionals, provider organizations, health plans, accrediting bodies, labor unions, supporting industries, and organizations involved in health care research or quality improvement. NQF has reviewed and endorsed measure sets applicable to several health care settings and clinical areas and services, including hospital care, home health care, nursing-sensitive care, nursing home care, cardiac surgery, and diabetes care (NQF, 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005).

The committee concludes that a standard national approach to the development of performance indictors is essential, and therefore recommends that the Department of Health and Human Services convene a panel of individuals with emergency and trauma care expertise to develop evidence-based indicators of emergency and trauma care system performance (3.3). This should be an independent, national process with the broad participation of every component of emergency care, and with the federal government playing a lead role in its promotion and funding. The development of the initial set of performance indicators should be completed within 18 months of the release of this report.

The measures developed should include structure and process measures, but evolve toward outcome measures over time. They should be nationally standardized so that comparisons can be made across regions and states. Measures should evaluate the performance of individual providers within the system, as well as that of the system as a whole. Measures should also be sensitive to the interdependence among the components of the system; for example, EMS response times may be adversely affected by ED diversions.

Furthermore, because an episode of emergency care can span multiple settings, each of which can have a significant impact on the final outcome, it is important that patient-level data from each setting be captured and combined. Currently it is difficult to piece together a complete picture of an episode of emergency care. To address this need, states should develop guidelines for the sharing of patient-level data from dispatch through post–hospital release. The federal government should support such efforts by sponsoring the development of model procedures that can be adopted by states to minimize their administrative costs and liability exposure as a result of sharing these data.

Measurement of Performance

Performance data should be collected on a regular basis from all of the emergency care providers in a community. Over time, emerging technologies may support more simplified and streamlined data collection methods, such as wireless transmission of clinical data and direct links to patient electronic health records. However, these types of technical upgrades would likely require federal financial support, and EMS personnel would have to be persuaded to transition from paper-based run records, which are less amenable to efficient performance measurement. The data collected should be tabulated in ways that can be used to measure, report on, and benchmark system performance, generating information useful for ongoing feedback and process improvement. Using their regulatory authority over health care services, states should play a lead role in collecting and analyzing these performance data.

While a full-blown data collection and performance measurement and reporting system is the desired ultimate outcome, the committee believes a handful of key indicators of regional system performance should be collected and promulgated as soon as possible. These could include, for example, indicators of 9-1-1 call processing times, EMS response times for critical calls, and ambulance diversions. In addition, consensus measurement of EMS outcomes could be applied to two to three sentinel conditions. For example, emergency care systems across the country might be tasked with providing data on such conditions as cardiac arrest (see Box 3-1), pediatric respiratory arrest, and major blunt trauma with shock. Data from the different system components would allow researchers to measure how well the system performs at each level of care (9-1-1, first response, EMS, and ED). In addition, registries could provide a rich source of data for use in research and identification of trends.

Public Dissemination of Information on System Performance

Public dissemination of performance data is crucial to drive the needed changes in the delivery of emergency care services. Dissemination could take various forms, including public report cards, annual reports, and state public health reports, which could be viewed either in hard copy format or on line. A key to success would be ensuring that important information regarding the performance of the community’s emergency care system could be retrieved by the public with a minimum of effort in a format that was highly organized and visually compelling.

Public dissemination of health care information is still in a state of development, despite the proliferation of such initiatives over the past two decades. Problems include the costs associated with data collection, the sensitivity of individual provider information, concerns about interpretation

|

BOX 3-1 Cardiac Arrest Registry to Enhance Survival A new 18-month initiative funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) is under way in Fulton County, Georgia. Cardiac Arrest Registry to Enhance Survival (CARES) is intended to develop a prototype national registry to help local EMS administrators and medical directors identify when and where cardiac arrest occurs, which elements of their EMS system are functioning properly in dealing with these cases, and what changes can be made to improve outcomes. The initiative is engaging Atlanta-area 9-1-1, EMS and first responder services, and EDs in systematically collecting minimum data essential to improving survival in cases of cardiac arrest and submitting these data to the registry. Area hospitals log on to a simple, Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA)-compliant website to report each patient’s outcome. Data compilation and analysis are conducted by researchers at Emory University. Using information gathered from the CARES registry, a community consortium organized by the American Heart Association (AHA) will orchestrate various community interventions to reduce disparities and improve outcomes among victims of cardiac arrest. CARES is designed to enable cities across the country to collect similar data quickly and easily, and use these data to improve cardiac arrest treatment and outcomes. Sudden cardiac arrest results from an abrupt loss of heart function and is the leading cause of death among adults in the United States. Its onset is unexpected, and death occurs minutes after symptoms develop (AHA, 2005). Survival rates in the event of sudden cardiac arrest are low, but vary as much as 10-fold across communities. Victims’ chances of survival increase with early activation of 9-1-1 and prompt handling of the call, early provision of bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), rapid defibrillation, and early access to definitive care. CARES is designed to allow communities to measure each link in their “chain of survival” quickly and easily and use this information to save more lives. |

of data by the public, and lack of public interest. There are many examples from which to learn—the Health Plan Employer Data and Information Set (HEDIS), which reports on managed care plans to purchasers and consumers; CMS’s reports on home health and nursing home care—the Home Health Compare and Nursing Home Compare websites, respectively (CMS, 2005a); and Hospital Compare from the Hospital Quality Alliance, which reports comparative quality data on hospitals (CMS, 2005b). A number of states and regional business coalitions have also developed report cards on

managed care plans and hospitals (State of California Office of the Patient Advocate, 2005). Because of the unique status of the emergency care system as an essential public service and the public’s limited awareness of the significant problems facing the system, the public is likely to take an active interest in this information. The committee believes dissemination of these data would have an important impact on public awareness and the development of integrated regional systems.

Public reporting can be at a detailed or aggregate level. Because of the potential sensitivity of performance data, they should initially be reported in the aggregate at the national, state, and regional levels rather than at the level of the individual provider. Prematurely reporting provider performance data could inhibit participation and divert providers’ resources to public relations rather than corrective efforts. At the same time, however, individual providers should have full access to their own data so they can understand and improve their individual performance, as well as their contribution to the overall system. Over time, information on individual provider organizations should become an important part of the public information on the system. Eventually, the data may be used to drive performance-based payment for emergency care.

Approaches for Reducing Barriers to Implementation

Institutional barriers to the adoption of integrated, regionalized care exist. These include payment systems and the legal framework that defines much of the structure of emergency care delivery.

Aligning Payments with Incentives

No major change in health care can take place without strong financial incentives. The way emergency care services are reimbursed reinforces certain modes of delivery that are inefficient and stand in the way of achieving the committee’s vision of emergency care. For example, under Medicare and Medicaid, prehospital providers do not receive payment unless they transport a patient to the hospital. This payment system makes it difficult for regional systems to implement treat and release or other innovative nontransport approaches that could result in better care for patients and more efficient system design. CMS and all other payers should eliminate this requirement and develop a payment system for prehospital care that reflects the costs of providing those services.

Similarly, many hospitals do not have a strong economic motivation to address the problems of ED crowding, boarding, and ambulance diversion. In fact, these practices may even benefit them financially. Several payment approaches could eliminate incentives that degrade emergency care. One is

to eliminate the discrepancies in reimbursement between scheduled and ED admissions that relate to differences in both payer mix and severity of illness. CMS should evaluate the effect of existing Diagnosis-Related Group (DRG) payments for elective admissions as opposed to patients admitted from the ED. For example, DRG payments could be adjusted to reflect the average costs of scheduled surgical admissions versus ED medical admissions at safety net hospitals. Care would have to be exercised to ensure that this did not result in physicians simply admitting their elective patients through the ED. Another method is to assess direct financial rewards or penalties for hospitals based on their management of patient throughput. Through its purchaser and regulatory power, CMS has the ability to drive hospitals to address and manage patient flow and ensure timely access to quality care for its clients. All payers, including Medicare, Medicaid, and private insurers, could also develop contracts that would penalize hospitals for chronic delays in treatment, ED crowding, and EMS diversions. One strategy would be to refuse to pay for inpatient care unless it was provided in a designated inpatient unit. CMS and JCAHO should lead the way in the development of innovative payment approaches that can accomplish these objectives. All payers should be encouraged to do the same. States with strong certificate of need (CON) laws could include boarding and diversion as criteria in CON decisions.

Adapting the Legal and Regulatory Framework

The way hospitals and EMS agencies deliver emergency care is shaped largely by federal and state laws—in particular, EMTALA, the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), and medical malpractice laws. The application of these laws to the actual provision of care is guided by regulatory rules and advisories, enforcement decisions, and court decisions, as well as by providers’ understanding of these. EMTALA and HIPAA are discussed below, and medical malpractice in Chapter 6.

EMTALA was passed in 1986 to prevent hospitals from refusing to serve uninsured patients and “dumping” them on other hospitals. EMTALA established a mandate for hospitals and physicians who provide emergency and trauma care to provide a medical screening exam to all patients and appropriately stabilize patients or transfer them to an appropriate facility if an emergency medical condition exists (GAO, 2001). This requirement applies regardless of patients’ ability to pay. This aspect of EMTALA and its impact on the availability of EDs, trauma centers, and on-call specialists are described in Chapter 2.

EMTALA also has implications for the regional coordination of care. The act was written to provide individual patient protections—it

focuses on the obligations of an individual hospital to an individual patient (Rosenbaum and Kamoie, 2003). The statute is not clearly adaptable to a highly integrated regional emergency care system in which the optimal care of patients may diverge from conventional patterns of emergency treatment and transport.

Until recently, EMTALA appeared to hinder the regional coordination of services in several specific ways—for example, requiring a hospital-owned ambulance to transport a patient to the parent hospital even if it is not the optimal destination for that patient; requiring a hospital to interrupt the transfer to administer a medical screening exam for a patient being transferred from ground transport to helicopter and using the hospital’s helipad; and limiting the ability of hospitals to direct nonemergent patients who enter the ED to an appropriate and readily available ambulatory care setting. Interim guidance published by CMS in 2003, however, appeared to mitigate these problems (DHHS, 2003). This guidance established, for example, that a patient visiting an off-campus hospital site that does not normally provide emergency care does not create an EMTALA obligation, that a hospital-owned ambulance need not return the patient to the parent hospital if it is operating under the authority of a communitywide EMS protocol, and that hospitals are not obligated to provide treatment for clearly nonemergency situations as determined by qualified medical personnel. Further, hospitals involved in disasters need not adhere strictly to EMTALA if operating under a community disaster plan. Despite these changes, however, uncertainty surrounding the interpretation and enforcement of EMTALA remains a damper on the development of coordinated, integrated emergency care systems.

In 2005, CMS convened a technical advisory group to study EMTALA and address additional needed changes (CMS 2005a,b,c). To date, the advisory group has focused on incremental modifications to the act.

While the recent CMS guidance and deliberations of the EMTALA advisory group are positive steps, the committee envisions a more fundamental rethinking of the act that would support and facilitate the development of regionalized emergency systems rather than simply addressing each obstacle on a piecemeal basis. The new EMTALA would continue to protect patients from discrimination in treatment while enabling and encouraging communities to test innovations in the design of emergency care systems, such as direct transport of patients to non–acute care facilities—dialysis centers and ambulatory care clinics, for example—when appropriate.

HIPAA was enacted to facilitate electronic transmission of data between providers and payers while protecting the privacy of patient health information. In protecting patient confidentiality, HIPAA can present certain challenges for providers, such as making it more complicated for a physician to send information about a patient to another physician for a consultation.

Regional coordination is based on the seamless delivery of care across multiple provider settings. Patient-specific information must flow freely between these settings—from dispatch to emergency response to hospital care—to ensure that appropriate information will be available for clinical decision making and coordination of services in emergency situations. Current interpretations of HIPAA would make it difficult to achieve the required degree of information fluidity.

Both EMTALA and HIPAA protect patients from potential abuses and serve invaluable purposes. As written and frequently interpreted, however, they can impede the exchange of lifesaving information and hinder the development of regional systems. The committee believes appropriate modifications could be made to both acts that would preserve their original purpose while reducing their adverse impact on the development of regional systems. The committee recommends that the Department of Health and Human Services adopt regulatory changes to the Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act and the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act so that the original goals of the laws will be preserved, but integrated systems can be further developed (3.4).

CURRENT APPROACHES

A number of current efforts to establish emergency care systems achieve some or all of the committee’s goals of coordination, regionalization, and accountability. Some are purely voluntary, while others have the force of state regulation. Some are local and regional in scope, while others are statewide or national. This section highlights several such efforts that provide insights for future initiatives.

The Maryland EMS and Trauma System

Maryland has a unique statewide system that coordinates all EMS and trauma activity throughout the state. The Maryland Institute for EMS Systems (MIEMSS) is an independent state agency governed by an 11-member board that is appointed by the governor. The system provides training and certification, has established statewide EMS protocols, coordinates care through a central communications center, and operates the air medical system in coordination with the Maryland State Police. The system is funded in part through a surcharge on state driver’s license fees.

Coordination

The key to coordination in Maryland is the statewide communications center, which coordinates all communications between EMS and other

components of the system. The center links ambulances, helicopters, and hospitals and enables direct communications between components at any time. For example, a paramedic in western Maryland can talk directly with a local ED physician or obtain on-line consultation with a specialty hospital in Baltimore. While the local 9-1-1 centers initiate dispatch, they are usually too busy to follow patients through the continuum of care. The statewide communications center provides support by maintaining communications links, providing medical direction, and maintaining continuity of care. The center has direct links to incident command to facilitate management of EMS resources as an event unfolds.

The state also is developing a new wireless digital capability that will connect EMS with other public safety entities (police, fire, emergency management, public health) throughout the state. In addition, the state has developed a County Hospital Alert Tracking System (CHATS) to monitor the status of hospitals and EMS assets so ambulances can be directed to less crowded facilities. This capability can also be applied to individual services—for example, patients with acute coronary syndrome can be directed to facilities based on the current availability of reperfusion suites. The Facility Resource Emergency Database system was designed to gather detailed information electronically from hospitals on bed availability, staffing, medications, and other critical capacity issues during disasters, but is also used to monitor and report on system capacity issues on a regular basis.

The state ensures coordination and compliance with protocols through its statewide training, provider designation, and licensure functions. In addition to providing EMS training and certification, the system offers statewide disaster preparedness training for members of the National Disaster Medical System.

Regionalization

While EMS and 9-1-1 are operated locally, they utilize statewide protocols that promote regionalization of services to designated centers. In addition to multiple trauma levels, these centers are designated for stroke, burn, eye, pediatric, perinatal, and hand referrals. A relatively new stroke protocol, for example, designates regional stroke care centers according to three levels: level I provides comprehensive stroke care; level II initial emergency management, including fibrinolytic therapy; and level 3 screening and immediate transport to a level I or II center. There is also a designated center for the injury of hands, a common form of trauma that requires specialized expertise, within a non–trauma center. The control of air medical services by the state facilitates the regionalization of care through the active operation of dispatch.

Accountability

The state monitors performance at the provider and system levels through a provider review panel that regularly evaluates the operation of the system. As a state agency, the system reports on its performance goals and improvements. Also, CHATS enables participating hospitals and the public to view the status of hospitals at all times through its website, including data on availability of cardiac monitor beds, ED beds, and trauma beds. Paper ambulance run sheets are being replaced with an electronic system so that data can be collected and analyzed quickly to facilitate real-time performance improvement.

Conclusion

While Maryland is relatively advanced in achieving the goals of coordination, regionalization, and accountability, it is not clear how easily its system could be replicated in other states. The system has benefited from strong and stable leadership in the state office, adequate funding, a high concentration of resources, and limited geography—features that many states do not currently enjoy.

Austin/Travis County, Texas

Austin/Travis County and four surrounding counties agreed to form a single EMS and trauma system to provide seamless care to emergency and trauma patients throughout the region. The initiative, 10 years in the making, started with a fragmented delivery system consisting of the Austin EMS system, 13 separate fire departments, and a 9-1-1 service run through the sheriff’s office that lacked any unified protocols. These different entities agreed to come together to form a unified system that would coordinate all emergency care within the region. The system operates through a Combined Clinical Council that includes representatives of the different agencies and providers within the geographic area, including fire departments, 9-1-1, EMS, air medical services, and corporate employers. This is a “third service” system—it is separate from fire and other public safety entities. The system is supported financially by the individual entities.

Coordination

Coordination of care is achieved through several means. A unified set of clinical guidelines was developed and is maintained by the system in accordance with current clinical evidence. These guidelines provide a common framework for the care and transport of patients throughout the

system. Any changes to the guidelines must be evaluated and approved by the Combined Clinical Council.

All providers in the region have a common set of credentials and are given badges that identify them as certified providers within the system, substantially reducing the multijurisdictional fragmentation that is common across metropolitan areas. In addition, there is no distinction within the system between volunteer and career providers. The integrated structure facilitates both incident command and disaster planning.

Regionalization

The unified system supports the regional emergency and trauma care system through clinical operating guidelines that determine the care and transport of all emergency and trauma patients. But the system is focused more on coordination and medical direction of EMS than on regionalization of care.

Accountability

A Healthcare Quality Committee is charged with reviewing the performance of the system and recommending specific actions to improve quality.

Palm Beach County, Florida

An initiative currently under way in Palm Beach County, Florida, is more limited in scope than the Maryland and Austin/Travis County systems. The goal of the initiative is to find regional solutions to the limited availability of physician specialists who provide on-call emergency care services. In spring 2004, physician leaders, hospital executives, and public health officials formed the Emergency Department Management Group to address this problem. The initiative is in the early stages of development, and approaches are evolving. One approach is to attack the rising cost of malpractice insurance for emergency care providers, which discourages specialists from serving on on-call panels. The organization is developing a group captive insurance company to offer liability coverage for physicians providing care in county EDs.

Coordination

The group is developing a web-based, electronic ED call schedule so the EMS system can track which specialists are available at all hospitals

throughout the county. This will enable the system to direct transport to the most appropriate facility based on a patient’s type of injury or illness.

Regionalization

The group is exploring the regionalization of certain high-demand specialties, such as hand surgery and neurosurgery, so that the high costs of maintaining full on-call coverage can be concentrated in a few high-volume hospitals, where the number of cases makes it feasible to maintain such coverage. Hospitals throughout the county would pay a “subscription fee” to support the cost of on-call coverage at designated hospitals. The fee would be set at a level below what it would cost to have hospitals manage their on-call coverage problems individually.

Accountability

The initiative includes the development of a countywide quality assurance program under which all hospitals would submit certain data elements for assessment. It is unclear at this time how far this system would go toward public disclosure of system performance.

San Diego County, California

San Diego County has a regionalized trauma system that is characterized by a strong public–private partnership between the county and its five adult and one children’s trauma centers. Public health, assessment, policy development, and quality assurance are core components of the system, which operates under the auspices of the state EMS Authority.

Coordination

A countywide electronic system (QA Net) provides the real-time status of every trauma center and ED in the county, including the reason for diversion status, ICU bed availability, and trauma resuscitation capacity. The system has been in place for over 10 years and is a critical part of the coordination of emergency and trauma care in the county.

A regional communications system serves as the backbone of the EMS and emergency and trauma care systems for both day-to-day operations and disasters. It includes an enhanced 9-1-1 system and a countywide network that allows all ambulance providers and hospitals to communicate. The network is used to coordinate decisions on EMS destinations and bypass information, and allows each hospital and EMS provider to know the status of every other hospital and provider on a real-time basis. Because the

system’s authority comes from the state to the local level, all prehospital and emergency hospital services are coordinated through one lead agency. This arrangement provides continuity of services, standardized triage, treatment and transport protocols, and an opportunity to improve the system as issues are identified.

Regionalization

The county is divided into five service areas, each of which has at least a level II trauma center. Adult trauma patients are triaged and transported to the appropriate trauma center, while the children’s trauma center provides care to all seriously injured children below the age of 14. Serious burn cases are taken to the University of California-San Diego Burn Center. The county is considering regionalization for other conditions, such as stroke and heart attack, based on the trauma model. The system includes the designation of regional trauma centers, designation of base hospitals to provide medical direction to EMS personnel, establishment of regional medical policies and procedures, and licensure of EMS services.

Accountability

Accountability is driven by a quality improvement program in which a medical audit committee meets monthly to review systemwide patient deaths and complications. The committee includes trauma directors; trauma nurse managers; the county medical examiner; the chief of EMS; and representatives of key specialty organizations, including orthopedic surgeons and neurosurgeons, as well as a representative for nondesignated facilities. A separate prehospital audit committee that includes ED physicians and prehospital providers also meets monthly and discusses any relevant prehospital issues.

A PROPOSAL FOR FEDERAL, STATE, AND LOCAL COLLABORATION THROUGH DEMONSTRATION PROJECTS

States and regions face a variety of situations, and no one approach to building EMS systems will achieve the goals discussed in this chapter. There is, for example, substantial variation across states and regions in the level of development of trauma systems; the effectiveness of state EMS offices and regional EMS councils; and the degree of coordination and integration among fire departments, EMS, hospitals, trauma centers, and emergency management. The baseline conditions and needs also vary. For example, rural areas face very different problems from those of urban areas, and an approach that works for one may be counterproductive for the other.

In addition to these varying needs and conditions, the problems involved are too complex for the committee to prescribe an a priori solution. A number of different avenues should be explored and evaluated to determine what does and does not work. Over time and over a number of controlled initiatives, such a process should yield important insights about what works and under what conditions. These insights could provide best-practice models that could be widely adopted to advance the nation toward the committee’s vision.

The process described here is one that could be supported effectively through federal demonstration projects. Such an approach could provide funding critical to project success; guidance for design and implementation; waivers from federal laws that might otherwise impede the process; and standardized, independent evaluations of projects and overall national assessment of the program. At the same time, the demonstration approach would allow for significant variations according to state and regional needs and conditions within a set of clearly defined parameters. The IOM report Fostering Rapid Advances in Health Care: Learning from System Demonstrations articulated the benefits of the demonstration approach: “There is no accepted blueprint for redesigning the health care sector, although there is widespread recognition that fundamental changes are needed…. For many important issues, we have little experience with alternatives to the status quo…the committee sees the launching of a carefully crafted set of demonstrations as a way to initiate a ‘building block’ approach” (IOM, 2002, p. 3).

The committee therefore recommends that Congress establish a demonstration program, administered by the Health Resources and Services Administration, to promote coordinated, regionalized, and accountable emergency care systems throughout the country, and appropriate $88 million over 5 years to this program (3.5). The essential features of the proposed program are described below.

Recipients

Grants would be targeted at states, which could define projects at the state, regional, or local level; cross-state collaborative proposals would be encouraged. Projects would be selected so as to ensure that each of the three goals discussed in this chapter would be well represented in the final set of projects. Grantees would be selected through a competitive process based on the quality of proposals, assessment of the likelihood of success in achieving the stated goal(s), and the potential sustainability of the approach after the end of the grant period. Proposals should explicitly address the implications of the proposed project for both pediatric and adult patients.

Purpose of the Grants

Grantees could propose approaches addressing one, two, or all three of the goals of coordination, regionalization, and accountability. Proposals would not have to address more than one goal, but doing so would not be discouraged.

Initiatives could be statewide, regional, or local and could include collaborations between adjacent states. Each proposal would be required to describe the proposed approach in detail, explain how it would achieve the stated goal(s), identify who would carry out the responsibilities associated with the initiative, identify the costs associated with its implementation, and describe how success would be measured. Proposals should describe the state’s current stage of development and sophistication with regard to the stated goal(s) and explain how the grant would be used to enhance system performance in that regard.

Grants could be used in a number of different ways. Grant funds could be used to enhance communications so as to improve coordination of services; of particular interest would be the development of centralized communications centers at the regional or state level. Grants could be used to establish convening and planning functions, such as the creation of a regional or state advisory group of stakeholders for the purposes of building collaboration and designing and executing plans to improve coordination. Grant funds could be used to hire consultants and staff to manage the planning and coordination functions, as well as to pay for data collection, analysis, and public reporting. In very limited circumstances, they could also be used to implement information systems for the purpose of improving coordination of services. Grant funds should not, however, be used for routine functions that would be performed in the absence of the demonstration project, such as the hiring or training of EMS providers or the purchase of EMS equipment. Funds could also be used to enhance linkages between rural and urban emergency services within broadly defined regions so as to improve rural emergency care through communications, telemedicine, training, and coordination activities.

Funding Levels

The committee proposes a two-phase program. In phase I, the program would fund up to 10 projects at up to $6 million over 3 years. Funding 10 projects would likely result in considerable variation in the types of projects proposed and the range of lessons learned. Based on successful results that appeared to be reproducible in other states, the program would launch phase II, in which smaller, 2-year demonstration grants—up to $2 million each—would be made available to up to 10 additional states. This phase

of the program would also include a technical assistance program designed to disseminate results and practical guidance to all states. Program administration would include evaluation of the program throughout its 5 years, including reports and public comments at 2.5 and 5 years after program initiation. The committee estimates funding for the program as follows:

-

Phase I grants: $60 million (over 3 years)

-

Phase II grants: $20 million (over 2 years)

-

Phase II technical assistance: $4 million (over 2 years)

-

Overall program administration: $4 million (over 5 years)

-

Total program funding: $88 million (over 5 years)

Granting Agency

No single federal agency has responsibility for the various components of the nation’s emergency care system. As noted earlier, this responsibility is currently shared among multiple agencies—principally NHTSA, HRSA, CDC, and the Department of Homeland Security (DHS). If, as recommended below, a lead agency is established to consolidate funding and provide leadership for these multiple activities, it would be the appropriate agency to lead this proposed effort. Until that consolidation occurs, however, the committee believes this demonstration program should be placed within HRSA. HRSA currently directs a successful, related demonstration program—Emergency Medical Services for Children (EMSC)—and sponsors the Trauma-EMS Systems Program, both of which share many of the broad goals of the proposed demonstration program. HRSA has already demonstrated a willingness and ability to collaborate effectively with other relevant federal agencies, including NHTSA, CDC, and, increasingly, DHS, and should be encouraged to consider them as partners in this enterprise.

NEED FOR SYSTEM INTEGRATION AND A FEDERAL LEAD AGENCY

If the process of redesigning the emergency and trauma care system to achieve the goals outlined by the committee is to be successful, it must be supported. As stated in Fostering Rapid Advances, “…we must both plant the seeds of innovation and create an environment that will allow success to proliferate. Steps must be taken to remove barriers to innovation and to put in place incentives that will encourage redesign and sustain improvements” (IOM, 2002, p. 3). The process used to redesign the system must include payment policies that reward successful strategies. It must recognize the interdependencies within emergency care and address systemic problems.

It must balance the interests of many different stakeholders. And it must involve leadership at many levels taking responsibility for creating change.