1

Introduction

The Institute of Medicine (IOM) report To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System (IOM, 2000) identified medication errors as the most common type of error in health care and attributed several thousand deaths to medication-related events. The report had an immediate impact. In response, Congress apportioned $50 million in fiscal year 2001 for a major federal initiative to improve patient safety research and directed the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) to establish a Center for Quality Improvement and Patient Safety. The American people also took notice: 51 percent of respondents to a national survey conducted in late 1999 reported closely following the media coverage on the report (Kaiser Family Foundation, 1999).1 The report’s impact has continued. Five years after its release, two members of the committee that produced the report (Leape and Berwick, 2005) reflected that it had led to:

-

Broader acceptance within the health care community that preventable medical errors are a serious problem.

-

A number of important stakeholders (for example, the federal government, the Veterans Health Administration, and the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations [JCAHO]) taking up the challenge to improve patient safety.

-

Accelerated implementation of safe health care practices. For example, JCAHO in 2003 required hospitals to implement a number of evidenced-based safe-care practices, and the Institute for Healthcare Im-

-

provement undertook its 100,000 Lives Campaign, aimed at fostering the use of safe practices.

Likewise, an article in Health Affairs reviewing the impact of To Err Is Human (Wachter, 2004) noted that the report had led to improved patient safety processes through stronger regulation (for example, expanded patient safety regulation by JCAHO). The article also pointed to the accelerated implementation of clinical information systems that can help reduce medication errors. In addition, progress had been made on workforce issues, particularly in hospitals through the emergence of hospitalists— physicians who coordinate the care of hospitalized patients. Overall, however, the review suggested that much more needed to be done. Examples cited were the limited impact of error reporting systems and scant progress in improving accountability.

The key messages of To Err Is Human were that there are serious problems with the quality of health care delivery; that these problems stem primarily from poor health care delivery systems, not incompetent individuals; and that solving these problems will require fundamental changes in the way care is delivered. A subsequent IOM report, Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century (IOM, 2001), took up the challenge of suggesting how the health care delivery system should be redesigned. It identified six aims for quality improvement: health care should be safe, effective, patient-centered, timely, efficient, and equitable (IOM, 2001).

The Quality Chasm report and the later IOM report, Patient Safety: Achieving a New Standard for Care (IOM, 2004), also emphasized the need for an information infrastructure to support the delivery of quality health care. The latter report called specifically for a national health information infrastructure to provide real-time access to complete patient information and decision-support tools for clinicians and their patients, to capture patient safety information as a by-product of care, and to make it possible to use this information to design even safer delivery systems (IOM, 2004).

To Err Is Human focused on injuries arising as a direct consequence of treatment, that is, errors of commission, such as prescribing a medication that has harmful interactions with another medication the patient is taking. Patient Safety focused not only on those errors, but also errors of omission, such as failing to prescribe a medication from which the patient would likely have benefited. Box 1-1 portrays in stark terms an example of the failure of the care delivery system to catch and mitigate a medication error and the tragic outcome that resulted.

MEDICATION ERRORS: THE MAGNITUDE OF THE CHALLENGE

Regardless of whether one considers errors of commission or omission, error rates for various steps in the medication-use process, adverse drug

|

BOX 1-1 The Betsy Lehman Case Betsy Lehman, a 39-year-old wife and mother of two and health reporter for the Boston Globe, was diagnosed with breast cancer in September 1993. She was admitted to the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston on November 14, 1994, for her third round of cyclophosphamide, a toxic chemotherapy agent. Betsy was participating in a dose-escalating phase 1 clinical trial in which higher-than-normal doses of the drug were being administered to wipe out cancer cells. She was undergoing a bone marrow transplant to restore immune and blood-forming cells. Betsy received the wrong dose of cyclophosphamide. The correct dose was 1,000 milligrams (mg) per square meter (m2) of body surface area, given each day for a total of 4 days (or, for her height and weight, a total of 4,000 mg/m2 or 6,520 mg infused over the 4-day course of therapy). But after reading the trial protocol, a physician fellow wrote the order as “4,000 mg/m2 × 4 days.” The erroneous dosing went unrecognized, and Betsy died as a result of the overdose on December 3, 1993. The error was not discovered until 10 weeks later, when her treatment data were entered into the computer for the clinical trial (Bohmer, 2003; Bohmer and Winslow, 1999). Experts at the hospital, as well as outside consultants, recognized that many factors contributed to this tragedy (Conway and Weingart, 2005). System issues included minimal double-checks, orders written by fellows without attending MD signoff, and unclear protocols that were not current and not easily available to RNs and pharmacists. Some dosages were written in total dose and some in daily dose formats, often in the same protocol. Maximum dose checking was not a feature of the pharmacy computer system. Both the patient and her family had felt that Betsy was not being listened to and mechanisms for reporting issues were not clear. When reporting did occur, it did not move up the organization in a timely fashion. Today, the hospital has a strong culture of safety and engages interdisciplinary groups of front-line clinicians in the design and implementation of chemotherapy protocols. There is an understanding that safe cancer care requires an extraordinarily high level of communication, coordination, and vigilance, with a strong focus on being aware of and acting on the incidence of errors (Gandhi et al., 2005). Authority to prescribe cancer chemotherapy is reserved for attending staff, and dosages must be expressed only in terms of daily dose. Computer system warnings prevent physicians from placing drug orders that exceed the safe maximum, and the computerized provider order entry system is extensively supported by online protocols and templates. Alerts such as a red “WARNING: HIGH CHEMOTHERAPY DOSE” appear on the screen. To override the computer and exceed current guidelines, doctors must show the pharmacist new scientific results that prove a higher dose may be safe and effective. Much has been done to encourage independent checks of prescribed doses by nurses and pharmacists, and staff have been explicitly authorized to question openly any presumed dosing error. The organization describes the key lessons learned in the 10 years since Betsy’s overdose as the importance of the engagement of governance and leadership, vigilance by all every day, support for victims of errors, system support for safe practice, interdisciplinary practice, and patient- and family-centered care (Conway and Weingart, 2005; Conway et al., 2006). |

event rates in various care settings, or estimates of the economic impact of drug-related morbidity and mortality, it is clear that medication safety represents a serious cause of concern for both health care providers and patients. Data from a variety of settings demonstrate that medication errors are common, although the frequency reported depends on the identification technique used and the definition of error employed.

A 1999 study in 36 hospitals and skilled nursing facilities found a 10 percent medication administration error rate (excluding wrong-time errors) (Barker et al., 2002). In observational studies of hospital outpatient pharmacies, prescription dispensing error rates of 0.2 to 10 percent have been found (Flynn et al., 2003). And in a national observational study of the accuracy of prescription dispensing in community pharmacies, the error rate was 1.7 percent—equivalent to about 50 million errors during the filling of 3 billion prescriptions each year in the United States (Flynn et al., 2003).

The mortality projections documented in To Err Is Human were derived from adverse event data collected in a New York State study (Brennan et al., 1991; Leape et al., 1991) and a Colorado/Utah study (Thomas et al., 2000). In these two studies, medication-related adverse events were found to be the most common type of adverse event—representing 19 percent of all such events. In a variety of studies, moreover, researchers have found even higher rates of inpatient adverse drug events than were observed in the New York State and Colorado/Utah studies (Classen et al., 1991; Bates et al., 1995b) using less restrictive definitions of adverse drug events and more rigorous detection methods. More recently, major studies have shown that many adverse drug events occur in the period after discharge from the hospital (Forster et al., 2003), in nursing homes (Gurwitz et al., 2000, 2005), and in ambulatory care settings (Gandhi et al., 2003; Gurwitz et al., 2003).

In a major recent study, moreover, researchers found high levels of errors of omission in the U.S. health care system across a wide range of measures. The chance of receiving high-quality care was only about 55 percent (McGlynn et al., 2003).

Nearly 10 years ago, researchers estimated that the annual cost of drug-related illness and death in the ambulatory care setting in the United States was approximately $76.6 billion (Johnson and Bootman, 1997). Using the same approach, this cost was estimated to be $177.4 billion in 2000 (Ernst and Grizzle, 2001).

MEASURES TO IMPROVE MEDICATION SAFETY

Efforts to improve medication safety are made at all levels of the health care system: by helping the patient avoid medication errors; by organizing

health care units so that care is delivered safely; by creating health care organizations (collections of health care delivery units) that foster safe care, for example, through training for health care workers; and by encouraging health care organizations to deliver safe care by such means as regulatory and fiscal measures. Many of these efforts are long-standing and predate To Err Is Human. Key examples of such efforts are described below.

Helping the Patient Avoid Medication Errors

Since the early 1980s, the People’s Medical Society has developed guidelines to help consumers avoid medication errors in hospitals and at community and mail-order pharmacies (Personal communication, Charles Inlander, March 25, 2005). Medication errors can also take place in the home, and in June 2004, the National Consumers League, jointly with the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), launched Take with Care, a public education campaign addressing the need to be careful when taking over-the-counter (OTC) pain relievers (National Consumers League, 2004).

Organizing Health Care Units to Deliver Care Safely

For more than a decade, many organizations have provided guidance on safe medication practices for health care delivery units. Since 1994 the Institute for Safe Medication Practices has provided guidance on eliminating medication errors through newsletters, journal articles, and communications with health care professionals and regulatory authorities. In 1996 the National Coordinating Council for Medication Error Reduction and Prevention began publishing a series of recommendations on strategies for reducing medication errors (NCCMERP, 2005). Professional organizations have also offered guidance on medication safety. For example, the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists has provided guidance on safe pharmacy practices in hospitals and integrated health systems. Recently, the American Academy of Pediatrics published guidelines on the prevention of medication errors in the pediatric inpatient setting (Stucky et al., 2003).

Following the publication of To Err Is Human, AHRQ funded studies to evaluate best practices. The agency commissioned the Evidence-Based Practice Center of the University of California, San Francisco–Stanford University to evaluate the evidence supporting a long list of proposed safe practices, including many related to medication (Shojania et al., 2001).

In 2003, the National Quality Forum (NQF) identified 30 practices that should be adopted in applicable care settings, including implementing a computerized prescriber order entry system (safe practice 12) (NQF, 2003). In addition, JCAHO has been active in fostering patient safety for many years. In 1995 it implemented a Sentinel Event Policy that encourages

the voluntary reporting of serious adverse events and requires the performance of root-cause analyses for such events. Beginning in 1998, JCAHO disseminated patient safety solutions via Sentinel Event Alerts, based on analyses of reported sentinel events. Since 2003, JCAHO has set annual National Patient Safety Goals (JCAHO, 2006). Many of these goals relate to medications; an example is goal 13: Encourage the active involvement of patients and their families in the patients’ care as a patient safety strategy.

In parallel with the development of guidance on the delivery of safe care, emerging technologies have been developed to improve safety. These include electronic prescribing that automates the medication ordering process; clinical decision-support systems (usually combined with electronic prescribing systems), which may include suggestions or default values for drug doses and checks for drug allergies, drug laboratory values, and drug– drug interactions; automated dispensing systems that dispense medications electronically in a controlled fashion and track medication use; bar coding for positive identification of patients, prescriptions, and medications; and computerized adverse drug event monitors that search patient databases for data that may indicate the occurrence of such an event.

Creating Health Care Organizations That Foster Safe Care

The full benefits of technologies for preventing medication errors will not be achieved unless a culture of safety is created within health care organizations that are adequately staffed with professionals whose knowledge, skills, and ethics make them capable of overseeing the medication management of patients who are vulnerable and unable to manage their medications knowledgeably themselves (IOM, 2004). Indeed, the first safe practice in the NQF report Safe Practices for Better Healthcare is the creation of a culture of safety (NQF, 2003). The IOM’s (2004) Patient Safety report outlined the elements of a culture of safety: a shared understanding that health care is a high-risk undertaking, recruitment and training with patient safety in mind, an organizational commitment to detecting and analyzing patient injuries and near misses, open communication regarding patient injury results, and the establishment of a just culture seeking to balance the need to learn from mistakes and the need to take disciplinary action (IOM, 2004).

Two of NQF’s safe practices relate to the need for adequate resources. Safe practice 3 calls for use of an explicit protocol to ensure an adequate level of nursing based on the institution’s usual patient mix and the experience and training of its nursing staff. Safe practice 5 calls for pharmacists to participate actively in the medication-use process, including, at a minimum, being available for consultation with prescribers on medication ordering, interpretation and review of medication orders, preparation of medica-

tions, dispensing of medications, and administration and monitoring of medications.

Establishing an Environment That Enables Health Care Organizations to Deliver Safe Care

Many important systems, including accreditation, information technology, education, and knowledge generation, foster safe medication use. Important developments have occurred in each of these areas since the release of To Err Is Human. The medication-related National Patient Safety Goals and associated requirements established by JCAHO are an example in the area of accreditation. With regard to information technology, several IOM reports have stressed the need for an information infrastructure to support the delivery of quality health care. A key element of this infrastructure is the development and implementation of national health care data standards. In May 2004, Secretary of Health and Human Services Thompson announced 15 health care data standards for use across the federal health care sector, building on an initial set of 5 standards adopted in March 2003 (DHHS, 2004). In 2003 the Accreditation Council on Graduate Medical Education promulgated new residency training work-hour limitations (ACGME, 2003), drawing on published research on the relationship between fatigue and errors. And in response to To Err Is Human, Congress apportioned $50 million to support patient safety research; in early 2005, AHRQ published the results of this research (AHRQ, 2005).

STUDY CONTEXT2

Attempts to improve medication safety must be considered against the background of a number of important contextual issues. First, it is essential to recognize the ubiquitous nature of the use of prescription and OTC drugs and of complementary and alternative medications in the United States. In the 2004 Slone Survey (Slone, 2005), 82 percent of adults reported taking at least one medication (prescription or OTC drug, vitamin/mineral, or herbal supplement) during the week preceding the interview, and 30 percent reported taking at least five medications. The three most commonly used drugs were all OTC—acetaminophen (used by 20 percent of the adult population in the week prior to the interview), aspirin, and ibuprofen. In 2003, 3.4 billion prescriptions were purchased in the United States; on average there were 11.8 prescriptions per person (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2004). Fifty-

five percent of the adults interviewed in the 2004 Slone Survey reported taking at least one prescription drug in the week prior to the interview, and 11 percent reported taking five or more such drugs (Slone, 2005). In the same survey, 42 percent of the adults surveyed reported taking vitamins and 19 percent herbal or other natural supplements.

Another key contextual issue is ongoing cost containment efforts. In recent years, these efforts have failed to limit increases in health care costs to the general inflation rate or less. National health spending in 2003 was $1.679 trillion, an increase of 7.7 percent over the previous year (Smith et al., 2005). This growth rate is not much below that for the previous year; in 2002 national health spending increased 9.3 percent over that in 2001 (Levit et al., 2004). U.S. prescription drug sales have been rising more rapidly yet. IMS Health Inc., a leading provider of information and consulting services to the pharmaceutical and health care industries, reported that prescription drug sales in the United States grew 8.3 percent to $235 billion in 2004, compared with $217 billion the previous year (IMS, 2005). This increase followed an 11.5 percent growth in 2003 over 2002 and an 11.8 percent growth in 2002 over 2001 (IMS, 2003, 2004). One critical implication of these figures relevant to this study is that efforts to control health care costs at the federal and state levels and within health care organizations mean that any new investments, including investments in medication safety, will need to be thoroughly justified.

Efforts to contain health care costs have had limited success because of a number of important cost drivers (IFoM, 2003). Innovative new pharmaceuticals are displacing older agents, which are usually cheaper because they are off patent. An aging population is leading to higher consumption of health care in general and pharmaceuticals in particular. A more demanding patient population is less accepting of restrictions on health care use for cost containment reasons. And a broader definition of treatable disease is increasing the demand for health care. Implementation of the Medicare prescription drug benefit is also likely to increase the demand for pharmaceuticals. The Administration’s Financial Year Budget projected that the net federal cost of the Medicare prescription drug benefit would be $37.4 billion in 2006, rising to $109.2 billion in 2015 (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2005).

The FDA is a key player in ensuring the safety of medications, both prescription and nonprescription. The FDA approves a drug for sale in the United States after determining that its clinical benefits outweigh its potential risks. After a drug has been approved, the FDA continues to assess its benefits and risks, primarily on the basis of reports made to the agency on the effects of its use. In 2004, withdrawal of the drug rofecoxib (Vioxx) by Merck & Co. Inc. for safety reasons increased public concern about the procedures used for assessing drug safety. In response to this concern, the

FDA requested that the IOM convene an ad hoc committee of experts (the IOM Committee on Assessment of the U.S. Drug Safety System) to conduct an independent assessment of the current system for evaluating and ensuring drug safety postmarketing.

Implementation of the Medication Modernization Act of 2003 (P.L. 108-173) will make the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) the largest purchaser of prescription drugs in the United States and a major player in the way prescription medications are used. The next few years will be a pivotal period as CMS decides how it will administer the prescription drug benefit. There will be opportunities for introducing into the drug benefit rules safety guidelines for both prescribing and dispensing, and to use pay-for-performance incentives to enhance adoption of whatever guidelines are proposed. Further, there will be opportunities for medication safety research arising from the data CMS will collect as part of the drug benefit (CMS, 2005).

CMS will also become an important driver of electronic prescribing standards, whose development and implementation are called for by the Medication Modernization Act. The Medicare Prescription Drug Benefit final rule (42 Code of Federal Regulations Parts 400, 403, 411, 417 and 423) requires that Part D sponsors (e.g., participating Prescription Drug Plans and Medicare Advantage Organizations) support and comply with such standards once they are in effect. The final rule does not require providers to write prescriptions electronically; if prescribers send prescription information electronically, however, they will have to use the standards.

STUDY CHARGE AND APPROACH

In this context, at the urging of the Senate Finance Committee, the United States Congress, through the Medicare Modernization Act of 2003 (Section 107(c)), mandated that CMS sponsor a study by the IOM to address the problem of medication errors. The IOM convened the Committee on Identifying and Preventing Medication Errors to conduct this study, with the following charge:

-

To develop a fuller understanding of drug safety and quality issues through the conduct of an evidence-based review of the literature, case studies and analysis. This review will consider the nature and causes of medication errors; their impact on patients; and the differences in causation, impact and prevention across multiple dimensions of health care delivery including patient populations, care settings, clinicians, and institutional cultures.

-

If possible, to develop estimates of the incidence, severity and costs of medication errors that can be useful in prioritizing resources for na-

-

tional quality improvement efforts and influencing national health care policy.

-

To evaluate alternative approaches to reducing medication errors in terms of their efficacy, cost-effectiveness, appropriateness in different settings and circumstances, feasiblity, institutional barriers to implementation, associated risk, and quality of evidence supporting the approach.

-

To provide guidance to consumers, providers, payers, and other key stakeholders on high-priority strategies to achieve both short-term and long-term drug safety goals, to elucidate the goals and expected results of such initiatives and support the business case for them, and to identify critical success factors and key levers for achieving success.

-

To assess opportunities and key impediments to broad nationwide implementation of medication error reductions, and to provide guidance to policy-makers and government agencies in promoting a national agenda for medication error reduction.

-

To develop an applied research agenda to evaluate the health and cost impacts of alternative interventions, and to assess collaborative public and private strategies for implementing the research agenda through AHRQ and other government agencies.

The committee comprised 17 members representing a range of expertise related to the scope of the study, as described below (see Appendix A for biographical sketches of the committee members). The committee addressed its charge by reviewing the salient research literature, government reports and data, empirical evidence, and additional materials provided by government officials and others. In addition, a workshop was held to augment the committee’s knowledge and expertise through more focused discussion of specific issues of concern, and to obtain input from a wide range of researchers, providers of health care services, and interested members of the public. The committee also commissioned several background papers to avail itself of expert, detailed, and independent analyses of some of the key issues beyond the time and resources of its members.

SCOPE OF THE STUDY

CMS determined that this study should focus on issues related to the safe, effective, appropriate, and efficient use of medications. As mentioned above, a parallel IOM committee, the Drug Safety Committee, was tasked with assessing the postmarketing surveillance system for medications. There is some overlap between the present study and the work of that committee. The two committees and their staffs have worked together closely to define common areas in the two studies and develop consistent sets of recommendations.

Definitions

Drugs and Dietary Supplements

This study addressed the quality of the five steps in the medication-use process: selecting and procuring by the pharmacy, selecting and prescribing for the patient, preparing and dispensing, administering, and monitoring effects on the patient. The study examined medication use in a wide range of care settings—hospital, long-term, and community. The term medication encompasses three broad categories of products—prescription and nonprescription drugs and dietary supplements—all regulated by the FDA (see Chapter 2).

According to the FDA (2004), a drug is defined as a substance that is recognized by an official pharmacopeia or formulary; intended for use in the diagnosis, cure, mitigation, treatment, or prevention of disease; intended to affect the structure or any function of the body (excluding food); and intended for use as a component of a medicine, but not a device or a component, part, or accessory of a device.

Biologic products (including vaccines, blood, and blood products) are a subset of drug products. Biologics are distinguished from other drugs by their manufacturing process—biological as opposed to chemical. Some biologics, principally vaccines (excluding their long-term effects), are within the scope of this study; blood and blood products and tissues for transplantation are excluded.

Drugs include both those that require a prescription and those that do not. Nonprescription drugs are usually termed over-the-counter (OTC). The characteristics of OTC drugs are such that the potential for misuse and abuse is low, consumers are able to use them successfully for self-diagnosable conditions, they can be adequately labeled for ease and accuracy of use, and oversight by health practitioners is not needed to ensure safe and effective use (FDA, 2005).

Dietary supplements, often called complementary and alternative medications, are another group of products often used for medicinal or general health purposes. The Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act of 1994 (P.L. 103-147) defined a dietary supplement as a product (other than tobacco) intended to supplement the diet that bears or contains one or more of the following dietary ingredients: a vitamin; a mineral; an herb or other botanical; an amino acid; a dietary substance for use by man to supplement the diet by increasing the dietary intake; or a concentrate, metabolite, constituent, extract, or combination of any ingredient cited above. While the primary emphasis of the study was on prescription and OTC drugs, attention was given to dietary supplements as well, and the discussion of drugs often applies also to the latter products.

Medication Error, Adverse Drug Event, and Adverse Drug Reaction

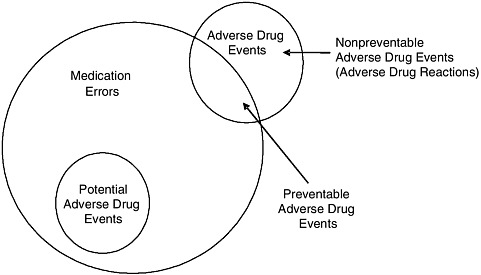

The terms medication error, adverse drug event, and adverse drug reaction denote related concepts (see Figure 1-1) and are often used incorrectly. To Err Is Human (IOM, 2000, p. 28) defined error and adverse event as follows:

An error is defined as the failure of a planned action to be completed as intended (i.e., error of execution), or the use of a wrong plan to achieve an aim (i.e., error of planning).

An adverse event is an injury caused by medical management rather than the underlying condition of the patient.

The Committee on Data Standards for Patient Safety was concerned that the phrase medical management did not embrace acts of omission. The committee gave considerable thought to expanding on these two definitions and produced the following (IOM, 2004, p. 30, 32):

An error is defined as the failure of a planned action to be completed as intended (i.e., error of execution), or the use of a wrong plan to achieve an aim (i.e., error of planning). An error may be an act of commission or an act of omission.

An adverse event results in unintended harm to the patient by an act of commission or omission rather than by the underlying disease or condition of the patient.

FIGURE 1-1 Relationship among medication errors, adverse drug events, and potential adverse drug events.

SOURCE: Gandhi et al., 2000.

The Committee on Data Standards for Patient Safety wanted to make clear that the potentially avoidable results of an underlying disease or condition—for example, a recurrent myocardial infarction in a patient without a contraindication who was not given a beta-blocker (an error of omission)—should be considered an adverse event (IOM, 2004). The Committee on Identifying and Preventing Medication Errors discussed the adverse event definition given in the Patient Safety report and decided to adopt this definition. Further attempts to operationalize the definition of adverse event may well lead eventually to additional modifications of the definition.

Consistent with the above definitions:

A medication error is defined as any error occurring in the medication use process (Bates et al., 1995a).

An adverse drug event is defined as any injury due to medication (Bates et al., 1995b).

An injury includes physical harm (for example, rash), mental harm (for example, confusion), or loss of function (for example, inability to drive a car).

Medication errors and adverse drug events have multiple sources. They may be related to professional practice; health care products, procedures, and systems, including prescribing; order communication; product labeling, packaging, and nomenclature; compounding; dispensing; distribution; administration; education of the patient or health care professional; and monitoring of use.

Implicit in the definition of medication errors is that they are preventable. However, most medication errors do not cause harm. Some do cause harm and are either potential adverse drug events or preventable adverse drug events (see Figure 1-1), depending on whether an injury occurred (Gandhi et al., 2000). Potential adverse drug events are events in which an error occurred but did not cause injury (for example, the error was detected before the patient was affected, or the patient received a wrong dose but experienced no harm) (Gandhi et al., 2000).

Adverse drug events can be preventable (for example, a wrong dose leads to injury) or nonpreventable (for example, an allergic reaction occurs in a patient not known to be allergic) (see Figure 1-1). Nonpreventable adverse drug events are also often termed adverse drug reactions3 (Gandhi et al., 2000).

The World Health Organization has defined an adverse drug reaction as a response to a drug that is noxious and unintended and occurs at doses normally used in man for prophylaxis, diagnosis, or therapy of disease or modification of physiological function (WHO, 1975). This definition excludes injuries due to drugs that are caused by errors, which are of obvious interest. As a result, drug safety researchers coined the term adverse drug event to include both adverse drug reactions (which are nonpreventable), and preventable adverse drug events (Bates et al., 1995b). From the safety perspective, preventable adverse drug events are most important because they are known to be preventable today; adverse drug reactions are also important, however, since it may become possible to prevent them in the future by using new approaches, such as pharmacogenomic profiling.

Audiences for the Report

The committee sought to assess the roles of and make recommendations for all of the major stakeholders involved in the safe use of medications:

-

First and foremost, the consumer4 or patient who uses a medication, as well as family members, friends, and neighbors who may be involved in assisting the patient.

-

Individual health care providers—physicians, nurses, and pharmacists.

-

The organizations responsible for delivering care, for example, hospitals, nursing homes, ambulatory clinics, pharmacies, and pharmacy benefit managers.

-

Those responsible for salient policy (Congress and state legislators), payment (CMS and commercial insurers), regulation (for example, the FDA and state regulatory bodies), accreditation (for example, JCAHO), and professional education (for example, schools of nursing).

-

Manufacturers of medications and the systems used in medication delivery (for example, intravenous pumps and health information technology systems) and providers of value-added services (for example, tools that indicate harmful drug–drug interactions).

In carrying out the study, the committee took the view that the goal of all these stakeholders with regard to medication use should be to optimize the relationship between the patient and the health care provider(s) so as to meet the six aims set forth in the Quality Chasm report (care should be safe, effective, timely, patient-centered, equitable, and efficient) (IOM, 2001). In

general, the health care system should enable the flow of all information needed to choose medications that optimize health to the extent possible in accordance with the preferences of the patient. In addition, all health care stakeholders should attempt to produce information on and inform patients and providers about the balance between effectiveness and safety, rather than addressing either in isolation. Effectiveness (tangible benefits— those that can be felt by the patient—in the actual setting in which the medication is used) rather than efficacy (benefit based on ideal circumstances of use) is the appropriate measure for the purpose of informing patients and providers. Further, all stakeholders should strive to produce a system in which the transactions that ensue following a decision about using a medication at a particular dose and time are free of errors.

REPORT OVERVIEW

Part I of this report addresses the causes, incidence, and costs of medication errors. By way of background, it begins with a case study illustrating how medication errors can arise through a combination of organizational and individual failures. Chapter 2 provides an overview of the system for drug development, regulation, distribution, and use, identifying the many points at which errors can occur. Chapter 3 summarizes the peer-reviewed literature on the incidence and costs of medication errors.

Part II of the report outlines the steps needed to establish a patient-centered, integrated medication-use system. It provides action agendas for achieving both short- and long-term improvements in medication safety for patients/consumers to support provider–consumer partnerships (Chapter 4), for health care organizations (Chapter 5), and for the industry that provides medications and medication-related products and services (Chapter 6). In Chapter 7, the committee outlines an applied research agenda designed to foster safe medication use. Finally, Chapter 8 proposes action agendas for those who set the environment in which care is delivered (for example, legislators, payers, and regulators). Appendix B provides a glossary and acronym list for the report, while Appendices C and D present detailed discussion of medication incidence rates and prevention strategies, respectively.

REFERENCES

ACGME (Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education). 2003. For Insertion into the Common Program Requirements for All Core and Subspecialty Programs by July 1, 2003: V.F. Resident Duty Hours and the Working Environment. [Online]. Available: http://www.acgme.org/acWebsite/dutyHours/dh_Lang703.pdf [accessed May 26, 2005].

AHRQ (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality). 2005. Advances in Patient Safety: From Research to Implementation. Vols. 1–4. Rockville, MD: AHRQ.

Barker KN, Flynn EA, Pepper GA, Bates DW, Mikeal RL. 2002. Medication errors observed in 36 health care facilities. Archives of Internal Medicine 162(16):1897–1903.

Bates DW, Boyle DL, Vander Vliet MB, Schneider J, Leape L. 1995a. Relationship between medication errors and adverse drug events. Journal of General Internal Medicine 10(4): 100–205.

Bates DW, Cullen DJ, Laird N, Petersen LA, Small SD, Servi D, Laffel G, Sweitzer BJ, Shea BF, Hallisey R, Vander Vliet M, Nemeskal R, Leape LL. 1995b. Incidence of adverse drug events and potential adverse drug events. Implications for prevention. ADE Prevention Study Group. Journal of the American Medical Association 274:29–34.

Bohmer R, Winslow A. 1999. The Dana-Farber Cancer Institute. HBS Case #699-025. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Publishing.

Bohmer RMJ. 2003. Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, The (TN). Harvard Business School Teaching Note 603-092. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Publishing.

Brennan TA, Leape LL, Laird NM, Hebert L, Localio AR, Lawthers AG, Newhouse JP, Weiler PC, Hiatt HH. 1991. Incidence of adverse events and negligence in hospitalized patients. Results of the Harvard Medical Practice Study I. New England Journal of Medicine 324(6):370–376.

Classen DC, Pestotnik SL, Evans RS, Burke JP. 1991. Computerized surveillance of adverse drug events in hospital patients. Journal of the American Medical Association 266:2847–2851.

CMS (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services). 2005. Speech by Administrator Mark B. McClellan, M.D., Ph.D., PCMA Drug Use Safety Symposium, May 11, 2005. [Online]. Available: http://www.pcmanet.org/events/presentation/McClellan%20Drug%20Data%20speech.pdf [accessed May 26, 2005].

Conway JB, Weingart SN. 2005. Organizational Change in the Face of Highly Public Errors: The Dana-Farber Cancer Institute Experience. [Online]. Available: http://www.webmm.ahrq.gov/perspective.aspx?perspectiveID=3 [accessed January 25, 2006].

Conway JB, Nathan DG, Benz EJ. 2006. Key Learning from the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute’s 10-Year Patient Safety Journey. American Society of Clinical Oncology: 2006 Education Book. Alexandria, VA: American Society of Clinical Oncology. Pp. 615–619.

DHHS (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services). 2004. Secretary Thompson, Seeking Fastest Possible Results, Names First Health Information Technology Coordinator: HHS Also Announces Milestones in Developing Health IT. [Online]. Available: http://www.hhs.gov/news/press/2004pres/20040506.html [accessed May 26, 2005].

Ernst FR, Grizzle AJ. 2001. Drug-related morbidity and mortality: Updating the cost-of-illness model. Journal of the American Pharmacists Association 41:192–199.

FDA (U.S. Food and Drug Administration). 2004. Drugs @ FDA: Glossary of Terms. [Online]. Available: http://www.fda.gov/cder/drugsatfda/glossary.htm [accessed June 7, 2005].

FDA. 2005. Office of Nonprescription Drugs. [Online]. Available: http://www.fda.gov/cder/offices/otc/default.htm [accessed June 7, 2005].

Flynn EA, Barker KN, Carnahan BJ. 2003. National observational study of prescription dispensing accuracy and safety in 50 pharmacies. Journal of the American Pharmacists Association 43(2):191–200.

Forster AJ, Murff HJ, Peterson JF, Gandhi TK, Bates DW. 2003. The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospital. Annals of Internal Medicine 138(3):161–167.

Gandhi TK, Seger DL, Bates DW. 2000. Identifying drug safety issues: From research to practice. International Journal for Quality in Health Care 12(1):69–76.

Gandhi TK, Weingart SN, Borus J, Seger AC, Peterson J, Burdick E, Seger DL, Shu K, Federico F, Leape LL, Bates DW. 2003. Adverse drug events in ambulatory care. New England Journal of Medicine 348(16):1556–1564.

Gandhi TK, Bartel SB, Shulman LN, Verrier D, Burdick E, Cleary A, Rothschild JM, Leape LL, Bates DW. 2005. Medication safety in the ambulatory chemotherapy setting. Cancer 104(11):2477–2483.

Gurwitz JH, Field TS, Avorn J, McCormick D, Jain S, Eckler M, Benser M, Edmondson AC, Bates DW. 2000. Incidence and preventability of adverse drug events in nursing homes. American Journal of Medicine 109(2):87–94.

Gurwitz JH, Field TS, Harrold LR, Rothschild J, Debellis K, Seger AC, Cadoret C, Fish LS, Garber L, Kelleher M, Bates DW. 2003. Incidence and preventability of adverse drug events among older persons in the ambulatory setting. Journal of the American Medical Association 289(9):1107–1116.

Gurwitz JH, Field TS, Judge J, Rochon P, Harrold LR, Cadoret C, Lee M, White K, LaPrino J, Mainard JF, DeFlorio M, Gavendo L, Auger J, Bates DW. 2005. The incidence of adverse drug events in two large academic long-term care facilities. American Journal of Medicine 118(3):251–258.

IFoM (International Forum on Medicine). 2003. Presentation of the Forum and Current Agenda Areas. The Hague, The Netherlands: International Pharmaceutical Federation.

IMS (Intercontinental Marketing Services). 2003. IMS Reports 11.5% Dollar Growth in 2002 U.S. Prescription Sales. [Online]. Available: http://imshealth.com/ims/portal/front/articleC/0,2777,6372_3665_41276589,00.html [accessed October 27, 2005].

IMS. 2004. IMS Reports 11.5 Percent Dollar Growth in ‘03 U.S. Prescription Sales. [Online]. Available: http://www.imshealth.com/ims/portal/front/articleC/0,2777,6599_40183881_44771558,00.html [accessed October 27, 2005].

IMS. 2005. IMS Reports 8.3 Percent Dollar Growth in 2004 U.S. Prescription Sales. [Online]. Available: http://ir.imshealth.com/phoenix.zhtml?c=67124&p=irol-newsArticle&ID=674505&highlight= [accessed October 27, 2005].

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2000. To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

IOM. 2001. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

IOM. 2004. Patient Safety: Achieving a New Standard for Care. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

JCAHO (Joint Commision on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations). 2006. Facts About the 2006 National Patient Safety Goals.[Online]. Available: http://www.jcipatientsafety.org/show.asp?durki=9726 [accessed August 16, 2006].

Johnson JA, Bootman JL. 1997. Drug-related morbidity and mortality and the economic impact of pharmaceutical care. American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy 54: 554–558.

Kaiser Family Foundation. 1999. Kaiser/Harvard Health News Index: November-December 1999. [Online]. Available: http://www.kff.org/kaiserpolls/upload/13350_1.pdf [accessed May 25, 2005].

Kaiser Family Foundation. 2004. Prescription Drug Trends—October 2004. [Online]. Available: http://www.kff.org/rxdrugs/3057-03.cfm [accessed October 26, 2005].

Kaiser Family Foundation. 2005. Medicare Fact Sheet: March 2005. [Online]. Available: http://www.kff.org/medicare/loader.cfm?url=/commonspot/security/getfile.cfm&PageID=33325 [accessed May 25, 2005].

Leape LL, Berwick DM. 2005. Five years after To Err Is Human: What have we learned? Journal of the American Medical Association 293(19):2384–2390.

Leape LL, Brennan TA, Laird N, Lawthers AG, Localio AR, Barnes BA, Hebert L, Newhouse JP, Weiler PC, Hiatt H. 1991. The nature of adverse events in hospitalized patients. Results of the Harvard Medical Practice Study II. New England Journal of Medicine 324(6):377–384.

Levit K, Smith C, Cowan C, Sensenig A, Catlin A, Health Accounts Team. 2004. Health spending rebound continues in 2002. Health Affairs (Millwood) 23(1):147–159.

McGlynn EA, Asch SM, Adams J, Keesey J, Hicks J, DeCristofaro A, Kerr EA. 2003. The quality of health care delivered to adults in the United States. New England Journal of Medicine 348(26):2635–2645.

National Consumers League. 2004. New Campaign Focuses on Preventing Common Medication Errors in the Home. [Online]. Available: http://www.nclnet.org/news/2004/take_with_care.htm [accessed May 25, 2005].

NCCMERP (National Coordinating Council on Medical Error Reduction and Prevention). 2005. National Coordinating Council on Medical Error Reduction and Prevention: Council Recommendations. [Online]. Available: http://www.nccmerp.org/councilRecs.html [accessed May 25, 2005].

NQF (National Quality Forum). 2003. Safe Practices for Better Healthcare: A Consensus Report. Washington, DC: NQF.

Shojania K, Duncan B, McDonald K, Wachter RM. 2001. Making Health Care Safer: A Critical Analysis of Patient Safety Practices. Rockville, MD: AHRQ.

Slone. 2005. Patterns of Medication Use in the United States 2004. Boston, MA: Slone Epidemiology Center at Boston University.

Smith C, Cowan C, Sensenig A, Catlin A, Health Accounts Team. 2005. Health spending growth slows in 2003. Health Affairs (Millwood) 24(1):185–194.

Strom BL (editor). 2005. Pharmacoepidemiology, 4th edition. Chichester, England: Wiley.

Stucky ER, American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Drugs, American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Hospital Care. 2003. Prevention of medication errors in the pediatric inpatient setting. Pediatrics 112(2):431–436.

Thomas EJ, Studdert DM, Burstin HR, Orav EJ, Zeena T, Williams EJ, Howard KM, Weiler PC, Brennan TA. 2000. Incidence and types of adverse events and negligent care in Utah and Colorado. Medical Care 38(3):261–271.

Wachter RM. 2004. The end of the beginning: Patient safety five years after “To Err Is Human.” Health Affairs (Millwood) (Suppl. Web Exclusives:W4):534–545.

WHO (World Health Organization). 1975. Requirements for Adverse Drug Reporting. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO.