4

Supporting a High-Quality EMS Workforce

Emergency medical services (EMS) is provided by dedicated professionals, both career and volunteer, who administer essential care to patients in need across the country. These services form a continuum of care that includes the dispatcher in the 9-1-1 emergency call center, fire and/or EMS personnel arriving on scene, and providers at the hospital emergency department (ED) or trauma center. How efficiently and effectively this care is delivered can mean the difference between life and death.

Qualifications for becoming an EMS provider vary widely nationwide. Education and training requirements and scope of practice designations are substantially different from one state to another, and limited reciprocity for providers seeking to move from one area of the country to another can pose a substantial burden. National efforts to promote greater uniformity have been progressing in recent years, but significant variation still remains.

EMS personnel face a difficult, often hazardous work environment, and they are not well paid. As a result, recruitment and retention are perennial challenges for EMS systems. However, surveys of EMS personnel indicate that many find their work to be highly rewarding. As the baby boomers reach retirement age and demand for EMS is expected to increase, it will be important to ensure that the available workforce is sufficient to meet that demand.

The first section of this chapter presents the committee’s findings and recommendations with regard to restructuring the requirements for EMS personnel. This is followed by an overview of the EMS workforce—its roles and responsibilities, demographics, and size. Next is a discussion of issues associated with recruitment and retention. The final two sections address

two key groups of ancillary EMS personnel: emergency medical dispatchers (EMDs) and EMS medical directors

RESTRUCTURING OF WORKFORCE REQUIREMENTS

EMS personnel have become part of the health care workforce only within the past 40 years. Over the past 10–15 years, concerted efforts have been made to change professional education and training standards for EMS personnel, as well as their scope of practice requirements. In 1993, a national, multidisciplinary consensus process culminated in the publication of the National EMS Education and Practice Blueprint (NREMT, 1993). This report sought to establish recognized levels of EMS personnel, nationally recognized scopes of practice, and frameworks for curriculum development and workforce reciprocity (NHTSA, 2000). The report established standard knowledge and practice expectations for four levels of EMS personnel: first responder, emergency medical technician (EMT)-B (Basic), EMT-I (Intermediate), and EMT-P (Paramedic). At the time, more than 40 different levels of EMT certification existed (NHTSA, 1996).

The 1996 report of the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) Emergency Medical Services Agenda for the Future included education systems as one of its 14 priority areas for improvement. The report emphasized the need to develop national core content for curricula for providers at various levels and asserted that all EMS education must be conducted with the benefit of qualified medical direction (NHTSA, 1996). Goals included in the report are detailed in Box 4-1.

The Emergency Medical Services Agenda for the Future: Implementation Guide, released in 1998, expanded upon these goals, providing specific objectives and timeframes for accomplishing the goals (NHTSA, 1998). The report emphasized the need to update and adopt the National EMS Education and Practice Blueprint to promote consistency in the levels of EMS practice, and asserted that core content for EMS curricula should comply with the guidelines of the Blueprint. In addition, the Implementation Guide advocated the creation of a system for reciprocity of EMS provider credentials, with the goal of eliminating legal barriers to intra- and interstate reciprocity (NHTSA, 1998).

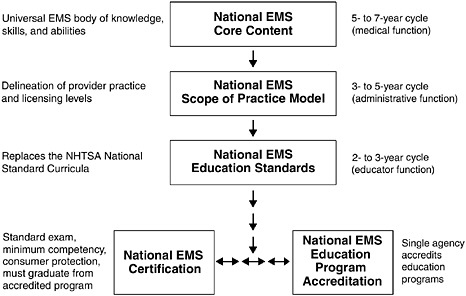

One of the outgrowths of the Emergency Medical Services Agenda for the Future was the development of the Emergency Medical Services Education Agenda for the Future: A Systems Approach, published in 2000 (NHTSA, 2000). The purpose of the Education Agenda was to create a more logical and uniform approach to EMS education and to maximize student competence. The report called for an education system with five integrated primary components: National EMS Core Content, National EMS Scope of Practice Model, National EMS Education Standards, National EMS

|

BOX 4-1 Education System Goals Set Forth in Emergency Medical Services Agenda for the Future

SOURCE: NHTSA, 1996. |

Education Program Accreditation, and National EMS Certification (see Figure 4-1).

Under this model, the Core Content forms the foundation for the Scope of Practice Model, and the Scope of Practice Model forms the foundation for the Education Standards (NHTSA and HRSA, 2005). Education Program Accreditation impacts the process for educating EMS personnel, and National Certification specifies the end product.

This vision for the future of EMS education has been partially developed since its initial release 6 years ago. Work on the National EMS Core Content and the Scope of Practice Model has been completed; the remaining components of the model are still in the development stage.

National EMS Core Content

The National EMS Core Content encompasses the entire domain of out-of-hospital medicine. It provides a list of knowledge, skills, and tasks required to provide care in out-of-hospital settings, detailing what EMS personnel must know and how they must practice (NHTSA and HRSA, 2005). The Core Content is broad enough so that state-of-the-art changes

FIGURE 4-1 The five primary integrated components of the EMS education system.

SOURCES: Adapted from NHTSA and HRSA, 2005.

and regional practice patterns can be incorporated within its framework (NHTSA, 2000).

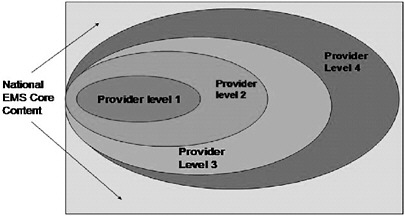

While the Emergency Medical Services Agenda for the Future: Implementation Guide sought to update and adopt the National EMS Education and Practice Blueprint, the Education Agenda suggested that the validity and utility of the Blueprint could be enhanced by separating the development of the core content and the scope of practice for the various provider levels. This approach allowed leadership for each of these elements to be assumed by the most appropriate group (see Figure 4-2) (NHTSA, 2000). The medical community is responsible for leading the development of the Core Content, with input from regulators and educators.

National EMS Scope of Practice Model

Based on the direction provided by the Education Agenda, the Blueprint was revised and renamed the National EMS Scope of Practice Model. This model defines, by name and by function, the levels of out-of-hospital EMS personnel based on the National EMS Core Content (NHTSA, 2000). Regulators are responsible for making these designations, with input from educators and physicians.

The National EMS Scope of Practice Model Task Force has created

FIGURE 4-2 Core content and scope of practice for various provider levels.

NOTE: The figure is illustrative only. It does not include the numbers and names of EMS provider levels determined by the process for the National EMS Scope of Practice Model.

SOURCES: NHTSA and HRSA, 2005.

a national model to aid states in developing and refining their scopes of practice and licensure requirements for EMS personnel. The purpose of the effort is not to impose national scope of practice standards, but to encourage greater consistency across the states. The committee supports this effort, but further recommends that state governments adopt a common scope of practice for emergency medical services personnel, with state licensing reciprocity (4.1). Doing so would promote greater uniformity in provider services across states and would alleviate current limitations relating to workforce mobility (see below).

The task force released its final report in 2005. The report describes scope of practice models for emergency medical responders (EMRs), EMTs, and paramedics. It also creates scope of practice standards for a new category of personnel termed advanced emergency medical technicians (AEMTs). Plans for a proposed advanced practice paramedic level have been deferred (NHTSA, 2005).

National EMS Education Standards

Curricula developed on behalf of the U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT) have provided the basis for the education of first responders, EMT-Bs, EMT-Is, and EMT-Ps. These National Standard Curricula (NSC) have undergone revision over time to reflect changes in accepted practice patterns and the evidence base for specific procedures. The curriculum for

first responders was updated most recently in 1995, that for EMT-Bs in 1994, that for EMT-Is in 1999, and that for EMT-Ps in 1998 (NHTSA, 2006). Because the revision of these NSC documents is the only setting in which national discussions regarding EMS scopes of practice occur, the revision process is time-consuming and expensive (NHTSA, 2000).

Education standards are needed to guide program managers and instructors in making appropriate decisions about what material to cover in classroom instruction. Currently, the content of most EMS education programs is based on the NSC. But while use of the NSC has contributed to the standardization of EMS education, the quality and length of programs still vary nationally, as do state licensure requirements for each position.

The NSC for basic life support (BLS) includes a minimum of 110 hours of didactic training, but states vary in their requirements from under 110 to more than 400 hours. For advanced life support (ALS) at the EMT-P level, applicants must receive 1,000 to 1,200 hours of didactic training beyond the EMT-B level, with additional practicum time (DOT, 1998); however states vary in their requirements from 270 to 2,000 hours (Mears, 2004). Based on the NSC, the EMT-I level requires 300 to 400 total training hours beyond the EMT-B level (DOT, 1998), but the number of hours varies across states from 50 to 492 (Mears, 2004).

The overwhelming majority of states and territories require both a written and a practical exam for initial credentialing (Mears, 2004). For all EMT levels and in all 50 states, a written exam is required, although the level of difficulty of these exams varies widely (NHTSA, 2000). All states require that licensure be renewed, typically every 2–3 years. Renewal usually entails completion of continuing education courses, verification of skills by a medical director, and current affiliation with an EMS provider (the latter requirement is common for ALS but less so for BLS). Standards for EMTs developed by the National Registry of Emergency Medical Technicians (NREMT) require initial training and recertification every 2 years.

Although state variation in educational requirements is substantial, the Education Agenda asserted that reliance on the highly prescriptive NSC has resulted in a significant loss of flexibility. The report concluded that a strict focus on the NSC could result in the development of narrow technical and conceptual skills without consideration for the broad range of professional competencies now expected of entry-level EMS personnel. The report advocated greater flexibility in meeting preestablished education standards, as well as more creativity in delivery methods, including problem-based learning and computer-aided instruction. However, the Education Agenda noted that accreditation of education programs and national certification need to be in place before the transition from the NSC to the National EMS Education Standards can take place (NHTSA, 2000).

EMS Education and Training Programs

The majority of EMTs and paramedics receive their education and training in programs offered by EMS agencies, community colleges, universities, hospitals and medical centers, fire departments, or private training programs. Increasing numbers of colleges offer bachelor’s degrees in EMS (Delbridge et al., 1998). However, medical education for EMS careers varies widely across the country, and it is frequently inadequate. Adherence to the NSC does not in itself ensure quality (NHTSA, 2000), and as noted, considerable state-level variation continues to exist.

This situation mirrors the challenges faced by the broader medical education system in the early 20th century. At the time, there were no standards for medical education programs and no adequate system to ensure quality. A report issued by Abraham Flexner in 1910 called for the establishment of more rigorous standards for medical education programs (Beck, 2004). Flexner visited 168 graduate and postgraduate medical schools in the United States and Canada and evaluated them on the basis of several criteria, including entrance requirements, faculty training, and financing to support the institution. The report was highly critical of the majority of schools visited. In the years following the report’s release, a large percentage of those schools closed, while others merged (Hiatt and Stockton, 2003). Consequently, the report is credited with triggering reforms in the standards, organization, and curriculum of medical schools across North America. In many respects, today’s EMS education system calls for a similar response.

The Education Agenda proposed national EMS education program accreditation as a way to address this problem. Currently, most states have some process for approving EMS education programs; however, these requirements vary widely. Some states require only that proper paperwork be filed (NHTSA, 2000). State education program approvals typically focus only on the paramedic level, and national accreditation is usually optional. The only nationally recognized accreditation available for EMS education is through the Committee on Accreditation of Emergency Medical Services Professions (CoAEMSP) under the auspices of the Commission on Accreditation of Allied Health Education Programs (CAAHEP). The Education Agenda advocated that a single national accreditation agency be identified and accepted by state regulatory offices.

The committee maintains that greater standardization and higher quality standards are needed to improve EMS education nationally and at the state level. Therefore, the committee recommends that states require national accreditation of paramedic education programs (4.2). However, the committee recognizes that this requirement would increase the cost of and thus likely reduce access to paramedic education in many states. Access to EMS education programs is a critical issue in many areas of the country but especially in rural states, where reasonable access is necessary for communities to train and

maintain sufficient numbers of EMS providers. There are many paramedic training programs in rural areas that do not fit typical “higher education” models and therefore would have a difficult time meeting accreditation standards. Cost is also an issue in that many municipal and volunteer services are already struggling to fund training. The committee recognizes that not all states are prepared to move to national accreditation requirements and proposes that the federal government provide technical assistance and possibly financial support to state governments to help with the transition.

National EMS Certification

Certification is designed to verify competency at a predetermined level of proficiency. The Education Agenda anticipated that national EMS certification would be accepted by all state EMS offices as verification of entry-level competency. It envisioned that all EMS graduates would complete an accredited program of instruction and would obtain national certification to qualify for state licensure. Certifying exams would be based on practice analysis and the National EMS Scope of Practice Model (NHTSA, 2000).

NREMT currently offers certification examinations for the first responder, EMT-B, EMT-I, and EMT-P levels, which are accepted by many states as evidence of competency (NHTSA, 1996). Two-thirds of the states use NREMT for initial credentialing of EMTs, and 84 percent of states use it for EMT-Ps (Mears, 2004).

The Education Agenda identified several barriers to the universal use of national exams, including the cost of implementation and administration, political issues, the use of a mandated practical exam, lack of local support, and perceived failure rates. Accordingly, it recommended a graduated phase-in plan whereby states would identify a timeline for adoption (NHTSA, 2000).

The committee supports the goals of the Education Agenda and recommends that states accept national certification as a prerequisite for state licensure and local credentialing of emergency medical services providers (4.3). This measure would support professionalism and consistency among and between the states. However, the committee is cognizant of the fact that requiring national certification would increase the cost of licensure—a significant issue for the volunteer workforce and also for EMS personnel generally, given their low wages. This, along with the difficulty of the national exams, could result in a reduction in the provider pool. While fewer, better-trained personnel may represent an improvement in the long run, this benefit must be weighed against the potential decline in the workforce available to respond to patients in many areas across the country.

For these and other reasons, the National Association of State EMS Officials (NASEMSO) has endorsed the Education Agenda, but on the

condition that no definite timetable be set for implementation. Within states there is still significant resistance to a national certification requirement, and some state legislatures have moved to reduce or remove these requirements. NHTSA and NASEMSO are currently ramping up an initiative to support states in their efforts to implement these components of the Education Agenda; however, state EMS directors remain concerned about reducing the overall number of EMS providers by changing current state requirements. The committee supports efforts to facilitate an eventual transition to national certification.

EMERGENCY MEDICAL SERVICES PERSONNEL

EMTs and paramedics are the backbone of prehospital emergency care in the United States. They provide essential care for patients in emergency situations and are frequently able to reduce patient morbidity and mortality. As noted earlier, although the work they do can be extremely arduous and is not well paid, surveys indicate that many EMS professionals find the job to be highly rewarding (Patterson et al., 2005).

Roles and Responsibilities of EMS Personnel

As described above, EMS personnel have different levels of training and qualifications. The scope of practice of first responders, EMT-Bs, EMT-Is, and EMT-Ps varies by state, but the tasks most commonly performed by each are detailed here (see Boxes 4-2, 4-3, 4-4, and 4-5). First responders provide basic care to patients. Many firefighters, police officers, and other emergency workers have this most basic level of training. They are typically the first to arrive on scene and are therefore able to provide vital care. For example, fire department first responders have been demonstrated to take significantly less time than ambulance attendants to provide defibrillation to victims (Shuster and Keller, 1993). Likewise, police first responders have been shown to perform well in using automated external defibrillators on victims of sudden cardiac arrest (Davis and Mosesso, 1998).

EMT-Bs are generally trained to provide basic, noninvasive prehospital care (although some states may allow them to perform selected invasive procedures). These personnel provide care to patients at the scene of a medical emergency and during transport to the hospital.

EMT-Is perform all the tasks of an EMT-B but may also perform some of the tasks of an EMT-P. The scope of practice for EMT-Is varies widely by state, but is always broader than the scope of practice for an EMT-B in the same state and narrower than the scope of practice for an EMT-P. Nationwide, there are over 40 identifiable versions of licensure between EMT-B and EMT-P.

|

BOX 4-2 Tasks Performed by the Majority of First Responders

SOURCE: NREMT, 2005. |

|

BOX 4-3 Tasks Performed by the Majority of EMT-Basics All tasks performed by first responders, plus:

SOURCE: NREMT, 2005. |

|

BOX 4-4 Tasks Performed by the Majority of EMT-Intermediates All tasks performed by EMT-Basics, plus:

SOURCE: NREMT, 2005. |

|

BOX 4-5 Selected Tasks Performed by the Majority of EMT-Paramedics All tasks performed by EMT-Basics and EMT-Intermediates, plus:

SOURCE: NREMT, 2005. |

EMT-Ps are the most highly skilled emergency medical workers, and they provide the most extensive care. They are trained in all phases of emergency prehospital care, including ALS treatment.

In addition to providing prehospital care, some EMTs now work as technicians in hospital EDs (Franks et al., 2004). These EMT-trained technicians are able to perform basic emergency care in the ED setting, allowing

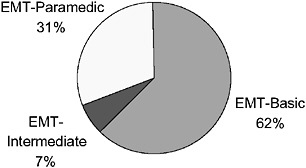

FIGURE 4-3 NREMT registration status of EMTs, United States, 2003.

SOURCE: NREMT, 2003.

nurses and physicians more time to treat complex cases and perform more intensive procedures. The scope of practice for such personnel is limited, but has increased in some EDs to include intravenous infusions, splinting, and phlebotomy.

The largest group of EMS personnel by far is EMT-Bs, who constituted 62.2 percent of all EMS personnel in 2003 (see Figure 4-3). EMT-Ps constituted another 31.3 percent, while only 6.5 percent were registered as EMT-Is. (Note that these data, and much of the data that follow, are based on the NREMT, which certifies a significant minority of EMS personnel in the United States. As described below, most states use the NREMT for initial licensure of EMT-Bs and EMT-Ps, but very few states require that registration be maintained. This likely results in a bias in the survey results that follow because the pool of respondents is probably younger and different in other ways from those who remain registered. However, broader data reflecting a more representative pool of EMS personnel are not available.)

Demographics of the EMS Workforce

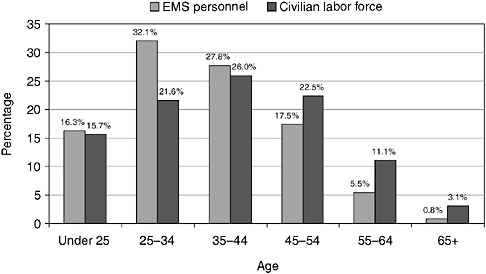

The majority of EMS personnel in the United States are young, white males, although in some rural jurisdictions, females outnumber males in the volunteer workforce. Fully 65 percent of EMS personnel nationwide were men in 2003, compared with 35 percent women. EMS personnel were also substantially younger than the U.S. civilian labor force as a whole (see Figure 4-4). In addition, EMT-Bs were younger than EMT-Ps (20.7 and 8.2 percent, respectively, were under age 25).

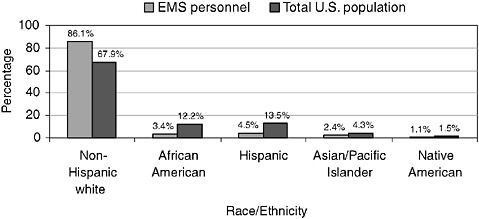

Finally, in 2003 the vast majority of EMS personnel were non-Hispanic white—86.1 percent, compared with 67.9 percent of the total U.S. population. African Americans, Hispanics, and Asians/Pacific Islanders were sub-

FIGURE 4-4 Age distribution of EMS personnel (2003) and the civilian labor force (2002), United States.

SOURCES: NREMT, 2003; BLS, 2004a.

FIGURE 4-5 Race/ethnicity of EMS personnel and the total U.S. population, 2003.

SOURCES: NREMT, 2003; U.S. Bureau of the Census, 2004.

stantially underrepresented relative to their percentage of the population (see Figure 4-5). Racial/ethnic distribution varied between urban and rural areas: while only 2.1 percent of EMS personnel in rural areas were African American and only 1.2 percent Hispanic, the numbers in large cities were 7.8 and 12.4 percent, respectively.

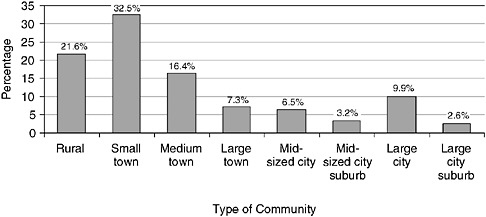

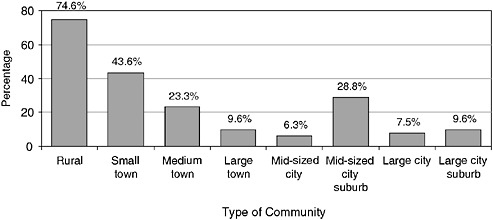

EMT is an occupation primarily of rural areas and small towns. In 2003, 32.5 percent of EMS personnel reported that they were employed in a small town, 21.6 percent that they were employed in a rural community, and 16.4 percent that they were employed in a medium-sized town. Only 9.9 percent of EMS personnel reported employment in a large city (see Figure 4-6).

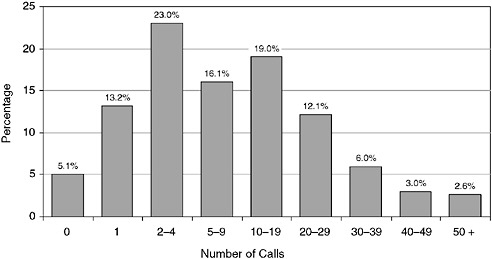

Reflecting this preponderance of employment in rural areas, the majority of EMS personnel (57.4 percent) responded to fewer than 10 calls per week in 2003 (see Figure 4-7). Among EMS personnel in rural communities, only 9.1 percent responded to 10 or more calls per week, versus 80.7 percent in large cities.

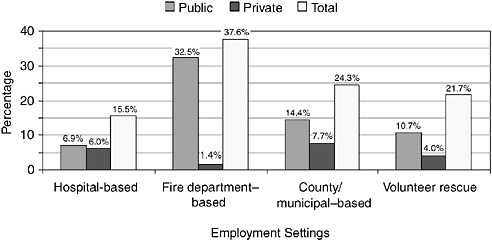

In urban areas, there has been an increasing trend for emergency medical/ambulance services to be assumed by municipal fire departments. In 2003, EMS personnel were most likely to be employed by fire department–based services (37.6 percent), followed by county- or municipal-based services (24.3 percent) and volunteer rescue services (21.7 percent). A smaller number of EMS personnel worked for hospital-based services (15.5 percent), including private ambulance companies (see Figure 4-8).

Size of the EMS Workforce

It is difficult to know how many EMS personnel are currently employed in the United States because registration requirements vary across states and because so many EMS personnel are volunteers (see Table 4-1). There were

FIGURE 4-6 Type of community in which EMS personnel employed, United States, 2003.

SOURCE: NREMT, 2003.

FIGURE 4-7 Number of calls responded to by EMS personnel per week, United States, 2003.

SOURCE: NREMT, 2003.

FIGURE 4-8 Public versus private employment settings of EMS personnel, United States, 2003.

SOURCE: NREMT, 2003.

192,182 EMTs in NREMT in 2004; as noted earlier, however, while many states require initial national registration for their EMS personnel, not all require that active EMTs maintain their national registration. As a result, the NREMT figure is in all likelihood an undercount. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) data show 192,000 EMTs employed nationwide in 2004. However,

TABLE 4-1 Estimates of the EMS Workforce in the United States

|

Type |

Description |

Number |

Source |

|

State-Licensed EMTs |

Individuals who, regardless of their employment status, are state-licensed as EMTs |

775,000 |

State licensure lists, 2005 |

|

Employer-Classified EMT Jobs |

Paid jobs classified by employers, regardless of training or licensure requirements, as “EMT” |

192,000 |

BLS, 2004 |

|

Nationally Registered EMTs |

Individuals who, regardless of their employment status, are nationally registered as EMTs |

192,182 |

NREMT, 2004 |

|

Self-Reported EMTs as Primary Paid Job |

Individuals who, regardless of training or licensure, self-report EMT as their primary paid employment |

132,000 |

2000 Census Public Use Microdata Sample |

|

SOURCES: NREMT, 2004; BLS, 2004b; Lindstrom, 2006. |

|||

these data are employer-reported and do not include volunteer EMS personnel. The 2000 Census Public Use Microdata Sample shows 132,398 EMTs employed as their primary job, but again, many EMT positions are only part-time or on a volunteer basis. Approximately 775,000 EMTs held state licenses in 2005, but this figure includes individuals who are no longer active EMTs and is likely an overcount.

BLS projects that EMS positions will increase by 59,000 between 2002 and 2012, an estimated growth rate of 33 percent. Total job openings for the period, including replacement positions, are estimated at 80,000 (BLS, 2004a).

Population growth and increasing urbanization are fueling this projected increase. The aging of the population will further stimulate demand for EMS, as older Americans will be more likely to have medical emergencies. Demand for EMS personnel will also continue to be strong in rural and smaller metropolitan areas (BLS, 2006). This is especially true given that it takes more EMS personnel to run a volunteer service now than was the case a decade ago (see below).

Even before factoring in this added demand, there is currently a perceived shortage of EMS personnel in the United States. This perception has been driven in part by reported shortages of paramedics in major cities such as Washington, D.C. In 2005, the District announced that 57 of its 166 paramedic positions were unfilled. As a result, 12 of its 14 ALS ambulances were being staffed by tiered units, including a paramedic and an EMT, rather than

TABLE 4-2 NREMT Exams per Year (Timeframe July 1–June 30)

|

|

2000 |

2001 |

2002 |

2003 |

2004 |

|

First Responder |

4,086 |

6,090 |

5,209 |

7,108 |

7,363 |

|

EMT-Basic |

46,346 |

63,067 |

65,398 |

75,594 |

83,692 |

|

EMT-Intermediate 85 |

5,243 |

5,900 |

5,284 |

5,169 |

5,413 |

|

EMT-Intermediate 95 |

|

332 |

439 |

681 |

1,327 |

|

Paramedic |

8,749 |

11,284 |

13,738 |

12,806 |

14,803 |

|

Total |

64,424 |

86,673 |

90,068 |

101,358 |

112,598 |

|

SOURCE: NREMT, 2004. |

|||||

two paramedics (Wilber, 2005). The decision as to the appropriate staffing of ambulance units is one factor determining whether a paramedic shortage is perceived to exist in any given jurisdiction. In addition, numerous issues relating to recruitment and retention of personnel play significant roles.

The number of personnel available for recruitment varies according to the number of individuals in the EMT education pipeline. For the most part, graduations from EMT education programs increased steadily from the 1995–1996 through the 2001–2002 academic years (National Center for Education Statistics, 2000). In addition, the number of individuals who were tested by NREMT increased markedly from 2000 to 2004 (see Table 4-2) (NREMT, 2004). However, the number of paramedics tested remained relatively flat during 2002–2004, perhaps contributing to the perceived shortage in many parts of the country.

NHTSA and the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) are currently funding an EMS Workforce for the 21st Century project that will provide a systematic assessment of the nation’s EMS workforce. The project will examine the future of the EMS workforce in the United States and establish a National EMS Workforce Policy Agenda. The project is managed by the Center for the Health Professions at the University of California-San Francisco.

RECRUITMENT AND RETENTION

EMS personnel have indicated in surveys that their work provides them with a sense of accomplishment and belonging in the community. However, overall job satisfaction is often very low because of concerns regarding personal safety, stressful working conditions, irregular hours, limited potential for career advancement, excessive training requirements, and modest pay and benefits (Cydulka et al., 1997; Brown et al., 2003; Patterson et al., 2005).

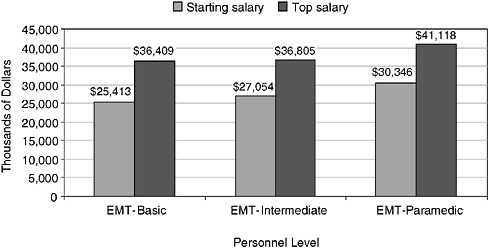

FIGURE 4-9 Average annual starting and top salaries for EMS personnel, United States, 2002.

SOURCE: Monosky, 2002.

Nationwide, salaries for EMS personnel in 2002 averaged between $25,413 (starting) and $36,409 (top) for EMT-Bs, between $27,054 and $36,805 for EMT-Is, and between $30,346 and $41,118 for EMT-Ps (see Figure 4-9). Salaries for EMS personnel have been increasing, but they are still lower than those for other health care professionals. For example, BLS data indicate that the mean average salary for registered nurses was $52,410 in 2004 (BLS, 2004b).

In addition, there is no well-defined career ladder for EMS personnel (Patterson et al., 2005). EMS personnel in fire department–based services sometimes must transition out of EMS work to assume other duties in order to advance within their organization. Others work as EMS personnel as a step toward becoming a physician assistant or a registered nurse.

Safety

Working conditions for EMS personnel are physically demanding and often dangerous. Injury rates for EMS workers are high; back injuries are especially common, as are other “sprains, strains, tears” (Maguire et al., 2005). The most dangerous times for EMS personnel are when they are inside an ambulance while it is moving or when they are working at a crash scene near other moving vehicles (Garrison, 2002). In addition, EMS personnel are frequently exposed to the threat of violence and other

unpredictable and uncontrolled situations (Franks et al., 2004). Moreover, EMS personnel can be exposed to potentially infectious bodily fluids and airborne pathogens.

As a result of the emotional and psychological stresses of their job, EMS personnel may experience burnout and even post-traumatic stress disorder. Moreover, Maguire and colleagues (2002) found that EMS workers’ occupational fatality rates were comparable to those of police and fire department personnel. The researchers estimated a rate of 12.7 fatalities per 100,000 EMS workers annually, compared with 14.2 for police, 16.5 for firefighters, and an overall national average of 5.0. These health and safety hazards for EMS personnel can contribute to high rates of job-related illnesses, low job satisfaction, and high turnover.

Workforce Mobility

Another key challenge is that EMS personnel who are licensed in one state but want to practice in another are often restricted in their ability to do so. As noted earlier, the legal scope of practice for EMS personnel is not consistent across states, and many states have extensive paperwork and testing requirements that can be burdensome for EMS personnel. For other professionals, such as physicians and nurses, transfer from one state to another is often much easier.

The Emergency Medical Services Agenda for the Future: Implementation Guide described the need to eliminate legal barriers to intra- and interstate reciprocity for EMS provider credentials. The committee supports this position, and maintains that reciprocity for licensing across states should be improved and requirements standardized. For example, paperwork requirements (e.g., diploma, current unencumbered license, continuing education credits) and testing requirements should be largely similar across states. While deciding which of the many different state requirements to standardize is challenging, improving reciprocity is an important objective that states should actively pursue. In addition, the movement toward national certification will help institute greater uniformity and will allow for improved reciprocity.

The Volunteer Workforce

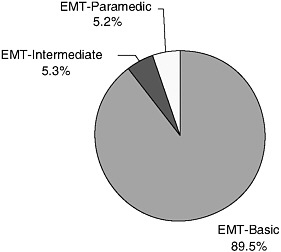

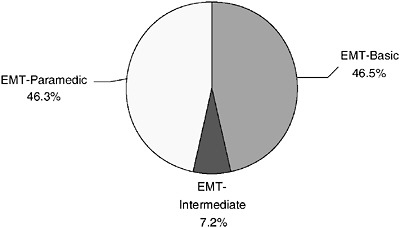

EMS is different from all other health care occupations in that a substantial number of its workers serve in a volunteer capacity. According to data gathered by NREMT, 36.5 percent of registered EMS personnel were volunteers in 2003. In some states, the number of EMS personnel who were volunteers was well above 50 percent. The vast majority of volunteer EMS personnel were EMT-Bs (89.5 percent). Figures 4-10a and 4-10b, respec-

tively, show the percentages of EMS personnel at the EMT-B, EMT-I, and EMT-P levels who are volunteers and paid employees.

In 2003, 75 percent of EMS personnel in rural areas were volunteers, compared with 7.5 percent in large cities (see Figure 4-11). Nearly 86 percent of rural EMTs were EMT-Bs, compared with 48.1 percent in large cities, where almost half of EMTs (47.7 percent) were EMT-Ps. As a result, rural Americans frequently do not have access to the same level of prehospital care as urban Americans.

Volunteer personnel have traditionally been the lifeblood of rural EMS agencies (see also Chapter 3). Since the development of EMS systems began in the 1960s, countless millions of hours have been contributed by rural EMS personnel to the care of neighbors, friends, and complete strangers. For a variety of reasons, however, volunteer staffing has become increasingly difficult.

The demographic characteristics of rural communities are changing rapidly. In many rural areas, the population is aging as younger residents move away. During the 1990s, more than 300 rural counties in the United States experienced a 15 percent or greater increase in their elderly population as a result of migration (IOM, 2004). This demographic shift can impact EMS systems in two ways; first, as noted earlier, increased demand on EMS systems is associated with a more fragile elderly population; second, the pool of potential volunteers is reduced. Moreover, those who migrate to rural areas from city environments often have unrealistic expectations of rural EMS systems and place considerable demands on the volunteer workforce.

In addition, the face of volunteerism is changing overall (Putnam, 2000). As discussed in Chapter 3, during the early stages of EMS, it was not uncommon for volunteers to be on call virtually 24 hours a day. Today there are more demands on volunteers’ time as a result of the need for two-income families, as well as competing interests, and volunteers are more likely to donate one specific weeknight or a few hours on a weekend. As a result, rural EMS agencies are faced with volunteer staffing shortages, particularly during the weekday work hours.

Demands on remaining volunteers have been exacerbated by the closure or restructuring of many rural hospital facilities. While these changes have increased the efficiency and viability of the remaining rural hospitals, they have increased the demands placed on rural EMS agencies because of the need for long-distance and time-consuming interfacility transfers. It is not uncommon for such transfers to keep volunteers away from their jobs or families for 3 to 6 hours or more.

New staffing models are needed for rural EMS systems. These might include consolidation and regionalization of transporting EMS programs, augmented locally by nontransporting quick-response units that provide immediate care and stabilization. Additionally, paid staffing, either alone or

FIGURE 4-10a Volunteer NREMT registrants, United States, 2003.

SOURCE: NREMT, 2003.

FIGURE 4-10b Paid NREMT registrants, United States, 2003.

SOURCE: NREMT, 2003.

to augment the volunteer force, must be considered. Finally, opportunities for rural prehospital personnel to expand their responsibilities within the health care or public health arena should be explored. Such opportunities would enable these personnel to receive competitive compensation while maintaining a variety of skills and contributing to the overall well-being of the community (McGinnis, 2004). Long undervalued, EMS must become an essential health care service that is publicly supported.

FIGURE 4-11 Percentage of volunteer EMS personnel by type of community, United States, 2003.

SOURCE: NREMT, 2003.

Bystander Care

Although not a part of the EMS workforce, bystanders are often first on the scene in emergency medical situations. Because time is such a crucial factor, they may be in the best position to render immediate care while EMS personnel are in transit. EMDs typically have protocols for delivering prearrival instructions to bystanders so they can administer such treatments as cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) for heart attack victims and the Heimlich maneuver for choking victims. Provision of instructions for CPR by telephone, for example, is associated with a 50 percent improvement in the odds of survival compared with cases in which no CPR is administered before the arrival of EMS (Rea et al., 2001; Idris and Roppolo, 2003).

As a result, efforts are under way to increase rates of bystander care, for example, through public service announcements (Becker et al., 1999). Such efforts are particularly important for minority populations, who are less likely to receive CPR training than whites (Brookoff et al., 1994). In addition, bystander training in CPR is shifting from lengthy programs offered in large classes to video self-instruction (Todd et al., 1999; Brennan and Braslow, 2000). Web-based formats for such training have also been developed.

Placement of automated external defibrillators (AEDs) in public areas such as airports provides bystanders with additional capabilities to provide needed care. Bystanders can thereby act as an extension of the emergency care workforce and dramatically improve outcomes for out-of-hospital emergency patients. The Public Access Defibrillation trial, the largest EMS clinical trial completed in the United States to date, found that the number of

survivors of sudden cardiac arrest increased substantially when the victims were helped by community volunteers trained to use CPR and an AED as compared with those aided by volunteers using CPR alone.

EMERGENCY MEDICAL DISPATCHERS

In responding to medical emergencies, EMDs are often the first link in the care continuum. Though they often are not viewed as part of the patient care team, EMDs serve three important medical functions: (1) they perform medical triage by assessing the patient’s needs; (2) they dispatch appropriate medical and rescue resources; and (3) as noted above, they sometimes provide prearrival instructions to bystanders, or patients themselves, on how to provide lifesaving first aid on scene.

When responding to calls, EMDs question each caller to determine the type, seriousness, and location of the emergency. They monitor the location of EMS personnel and dispatch the appropriate type and number of units. In a medical emergency, EMDs keep in close touch not only with the dispatched units, but also with the caller. They also give updates on the patient’s condition to ambulance personnel who are en route (BLS, 2004a).

Not all emergency dispatchers are trained EMDs. Many are public safety communicators, often fire or police department–based. In many cases, emergency calls are initially fielded by these emergency communicators at a primary call center and then transferred to EMDs at a secondary call center. In many other instances, the primary call center handles all calls, and no EMDs are available.

EMDs are required to undergo education and training to receive their designation. Training for EMDs is conducted mainly by private companies using their own curriculum. NHTSA sought to develop a national standard EMD curriculum in the early 1990s (similar to the curricula for other levels of EMS personnel); however, dispatch protocols for the curriculum were never completed.

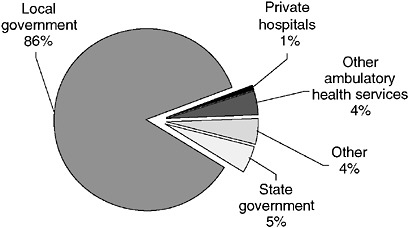

Generally, EMDs are poorly paid, and given the stress associated with their jobs, it is not surprising that 9-1-1 call centers experience high rates of turnover. The median annual salary for EMDs in 2003 was below $29,000 (BLS, 2004b). The vast majority of EMDs (85.9 percent) work for local governments (see Figure 4-12). A smaller number (4.7 percent) work for state governments and for private health providers (BLS, 2004a).

A sizable portion of 9-1-1 calls received by public safety answering points (PSAPs) are not emergency calls. One former Philadelphia fire EMS medical director calculated that only 18 percent of calls received by the local PSAP in 1 year could be classified as emergency calls (Davidson, 1995). In Fort Worth, Texas, up to 60 percent of 9-1-1 calls that received an EMS response were later classified as not requiring emergency services (Neely,

FIGURE 4-12 Employment setting for EMDs, 2002.

SOURCE: BLS, 2004a.

1996). However, these calculations were performed retrospectively, and they mask the difficulty of distinguishing between calls requiring ambulance service and those that could be handled safely through delivery to the hospital in a private vehicle.

Studies in both the United States and the United Kingdom have shown that dispatch criteria can safely identify 9-1-1 calls that do not need an on-scene response (Dale et al., 2000; Smith et al., 2001; Snooks et al., 2002). The successful referral of such calls has the potential to relieve ED and hospital crowding by diffusing demand for care over a wider range of resources. Recent experience in Richmond, Virginia, indicates that, based on a review of dispatch determinants and volume, call referrals can reduce on-scene responses by approximately 15 percent.

EMS MEDICAL DIRECTORS

EMS care has been called “medical care on wheels.” Accordingly, nonphysician EMS personnel, whether dispatchers, fire department first responders, EMTs, or paramedics, are required to operate under the orders of a physician medical director. This is especially true of paramedics, who, as detailed earlier, perform the most extensive out-of-hospital medical procedures. In a few communities, such as Seattle, Pittsburgh, Milwaukee, Atlanta, and Houston, highly qualified and experienced EMS physicians provide medical oversight for EMS personnel. In other communities, the medical director is little more than a figurehead.

Anecdotal evidence suggests the importance of strong medical direction

in improving outcomes for out-of-hospital emergency care (Davis, 2003b), a view widespread within the field (NRC, 1981; ACEP, 2005). Currently, however, such oversight is minimal in many areas of the country, largely because of funding constraints, but also political and cultural issues (Davis, 2003a). In many cases, medical direction is a contracted service provided through a bid process, with the medical director reporting to the fire chief or the head of the EMS agency. This system forces physicians to compete against each other in terms of cost, and in many cases the rigorousness of the medical direction provided, so that the system is subject to considerable internal conflict. The result is that often there is minimal medical oversight, and physicians face the constant threat of being underbid. Recognizing these limitations, the committee maintains that each EMS system should have highly involved and engaged medical directors who can help ensure that EMS personnel are providing high-quality care based on current standards of evidence.

Medical direction of EMS systems has several components, including on-line (direct) and off-line (indirect) medical oversight. On-line direction involves providing direct orders to EMS field personnel regarding the care of specific patients. Such direction is usually provided over the radio or telephone by a physician at the receiving hospital, although there are other, more centralized models. Off-line medical direction involves providing medical oversight through education, protocol development, and quality assurance. Such direction is typically provided by physicians who are paid or volunteer to serve as the medical director of a local, regional, or state EMS system.

The qualifications for medical directors differ considerably among EMS systems. As a result, the training and experience of EMS medical directors are highly variable. While the National Association of EMS Physicians and the American College of Emergency Physicians have jointly developed guidelines that address the qualifications and role of EMS medical directors, these guidelines are not universally recognized. Over the past decade, an increasing number of residency-trained emergency physicians have completed a 1- or 2-year EMS fellowship program developed by the Society of Academic Emergency Medicine (Marx, 1999). Graduates of these programs are increasingly involved in academic pursuits, including research and direction of EMS systems. Nonetheless, there are currently limited opportunities for emergency physicians to become certified as subspecialists in EMS. While the American Board of Osteopathic Emergency Medicine has established a subspecialty in EMS for its diplomates, the American Board of Emergency Medicine has yet to follow suit.

The 1998 Emergency Medical Services Agenda for the Future: Implementation Guide called for the designation of EMS as a physician subspecialty (see Box 4-6). The committee supports this position and recom-

|

BOX 4-6 EMS Physician Subspecialty Objectives Short Term: Continue to work to define the specific knowledge and expertise required of physicians who specialize in EMS. Intermediate Term: Enable the American Board of Emergency Medicine (ABEM) to sponsor an EMS subspecialty. Long Term: Petition the American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS) to designate EMS as a physician subspecialty. SOURCE: NHTSA, 1998. |

mends that the American Board of Emergency Medicine create a subspecialty certification in emergency medical services (4.4). The certification would be analogous to those available in toxicology, sports medicine, and pediatric emergency medicine. Creating this type of designation would acknowledge the unique challenges and complexities of the out-of-hospital environment. The certification would ensure that physicians providing medical direction would be trained specifically in prehospital EMS and prepared to meet the challenges likely to be encountered.

SUMMARY OF RECOMMENDATIONS

4.1: State governments should adopt a common scope of practice for emergency medical services personnel, with state licensing reciprocity.

4.2: States should require national accreditation of paramedic education programs.

4.3: States should accept national certification as a prerequisite for state licensure and local credentialing of emergency medical services providers.

4.4: The American Board of Emergency Medicine should create a subspecialty certification in emergency medical services.

REFERENCES

ACEP (American College of Emergency Physicians). 2005. Medical Direction of Prehospital Emergency Medical Services. [Online]. Available: http://www.acep.org/webportal/PracticeResources/issues/ems/PREPMedicalDirectionofPrehospitalEmergencyMedicalServices.htm [accessed November 1, 2005].

Beck AH. 2004. STUDENTJAMA. The Flexner report and the standardization of American medical education. Journal of the American Medical Association 291(17):2139–2140.

Becker L, Vath J, Eisenberg M, Meischke H. 1999. The impact of television public service announcements on the rate of bystander CPR. Prehospital Emergency Care 3(4):353–356.

BLS (Bureau of Labor Statistics). 2004a. 2002 National, State, Metropolitan Area, and Industry-Specific Occupational Employment and Wage Estimates.

BLS. 2004b. Occupational Employment Statistics: National Industry-Specific Occupational Employment and Wage Estimates (NAICS 621900: Other Ambulatory Health Care Services). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Labor.

BLS. 2006. Occupational Outlook Handbook, 2006–2007 Edition: Emergency Medical Technicians and Paramedics. [Online]. Available: http://www.bls.gov/oco/ocos101.htm [accessed March 5, 2006].

Brennan RT, Braslow A. 2000. Video self-instruction for cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Annals of Emergency Medicine 36(1):79–80.

Brookoff D, Kellermann AL, Hackman BB, Somes G, Dobyns P. 1994. Do blacks get bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation as often as whites? Annals of Emergency Medicine 24(6):1147–1150.

Brown WE Jr, Dawson D, Levine R. 2003. Compensation, benefits, and satisfaction: The Longitudinal Emergency Medical Technician Demographic Study (LEADS) project. Prehospital Emergency Care 7(3):357–362.

Cydulka RK, Emerman CL, Shade B, Kubincanek J. 1997. Stress levels in EMS personnel: A national survey. Prehospital & Disaster Medicine 12(2):136–140.

Dale J, Williams S, Foster T, Higgins J, Crouch R, Snooks H, Sharpe C, Glucksman E, George S. 2000. The Clinical, Organisational and Cost Consequences of Computer-Assisted Telephone Advice to Category C 999 Ambulance Service Callers: Results of a Controlled Trial. Final Report 2000. [Online]. Available: http://medweb.bham.ac.uk/emerg/ASTAP%20report.pdf [accessed May 24, 2006].

Davidson SJ. 1995. The Comm Center: Gate Keeper or Access Facilitator? Presentation at the meeting of the Sand Key II Conference, St. Petersburg Beach, FL.

Davis EA, Mosesso VN Jr. 1998. Performance of police first responders in utilizing automated external defibrillation on victims of sudden cardiac arrest. Prehospital Emergency Care 2(2):101–107.

Davis R. 2003a. Doctors in charge rarely call the shots. [Online]. Available: http://www.usatoday.com/news/nation/ems-day2-directors.htm [accessed January 27, 2007].

Davis R. 2003b. Only strong leaders can overhaul EMS. USA Today. [Online]. Available: http://www.usatoday.com/news/nation/ems-day3-cover.htm [accessed January 27, 2007].

Delbridge TR, Bailey B, Chew JL Jr, Conn AK, Krakeel JJ, Manz D, Miller DR, O’Malley PJ, Ryan SD, Spaite DW, Stewart RD, Suter RE, Wilson EM. 1998. EMS agenda for the future: Where we are … where we want to be. Prehospital Emergency Care 2(1):1–12.

DOT (U.S. Department of Transportation). 1998. EMT-Paramedic: National Standard Curriculum. [Online]. Available: http://www.nhtsa.dot.gov/people/injury/ems/EMT-P/ [accessed April 24, 2006].

Franks PE, Kocher N, Chapman S. 2004. Emergency Medical Technicians and Paramedics in California. San Francisco, CA: University of California, San Francisco Center for the Health Professions.

Garrison HG. 2002. Keeping rescuers safe. Annals of Emergency Medicine 40(6):633–635.

Hiatt MD, Stockton CG. 2003. The impact of the Flexner report on the fate of medical schools in North America after 1909. Journal of American Physicians and Surgeons 8(2):37–40.

Idris AH, Roppolo L. 2003. Barriers to dispatcher-assisted telephone cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Annals of Emergency Medicine 42(6):738–740.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2004. Quality through Collaboration: The Future of Rural Health. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Lindstrom AM. 2006. 2006 JEMS platinum resource guide. Journal of Emergency Medical Services 31(1):42–56, 101.

Maguire BJ, Hunting KL, Smith GS, Levick NR. 2002. Occupational fatalities in emergency medical services: A hidden crisis. Annals of Emergency Medicine 40(6):625–632.

Maguire BJ, Hunting KL, Guidotti TL, Smith GS. 2005. Occupational injuries among emergency medical services personnel. Prehospital Emergency Care 9(4):405–411.

Marx JA. 1999. SAEM emergency medical services fellowship guidelines. SAEM EMS Task Force. Academic Emergency Medicine 6(10):1069–1070.

McGinnis K. 2004. Rural and Frontier Emergency Medical Services Agenda for the Future. Kansas City, MO: National Rural Health Association.

Mears G. 2004. 2003 Survey and Analysis of EMS Scope of Practice and Practice Settings Impacting EMS Services in Rural America: Executive Brief and Recommendations. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Department of Emergency Medicine.

Monosky KA. 2002. JEMS’ 2002 EMS salary and workplace survey: Quantifying the tangible rewards of a career in EMS. Journal of Emergency Medical Services 27(10):30–46.

National Center for Education Statistics. 2000. Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS). [Online]. Available: http://nces.ed.gov/ipeds/data.asp [accessed January 12, 2006].

Neely K. 1996. In the starting gates once again, managed care in EMS. NAEMSP News 5(4).

NHTSA (National Highway Traffic Safety Administration). 1996. Emergency Medical Services Agenda for the Future. Washington, DC: Department of Transportation.

NHTSA. 1998. Emergency Medical Services Agenda for the Future: Implementation Guide. Washington, DC: Department of Transportation.

NHTSA. 2000. Emergency Medical Services Education Agenda for the Future: A Systems Approach. Washington, DC: Department of Transportation.

NHTSA. 2005. The National EMS Scope of Practice Model. Washington, DC: Department of Transportation.

NHTSA. 2006. National Standard Curricula. [Online]. Available: http://www.nhtsa.dot.gov/people/injury/ems/nsc.htm [accessed January 25, 2006].

NHTSA, HRSA (NHTSA, Health Resources and Services Administration). 2005. National EMS Core Content: The Domain of EMS Practice. Washington, DC: NHTSA, HRSA.

NRC (National Research Council). 1981. Medical Control in Emergency Medical Services Systems: Report of the Subcommittee on Medical Control in EMS Systems. Washington, DC: National Academy of Sciences.

NREMT (National Registry of Emergency Medical Technicians). 1993. National Emergency Medical Services Education and Practice Blueprint. Columbus, OH: NREMT.

NREMT. 2003. Longitudinal Emergency Medical Technician Attributes and Demographics Survey (LEADS) Data. [Online]. Available: http://www.nremt.org/about/lead_survey.asp [accessed February 24, 2006].

NREMT. 2004. 2004 Annual Report. Columbus, OH: NREMT.

NREMT. 2005. National EMS Practice Analysis. Columbus, OH: NREMT.

Patterson PD, Probst JC, Leith KH, Corwin SJ, Powell MP. 2005. Recruitment and retention of emergency medical technicians: A qualitative study. Journal of Allied Health 34(3):153–162.

Putnam RD. 2000. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Rea TD, Eisenberg MS, Culley LL, Becker L. 2001. Dispatcher-assisted cardiopulmonary resuscitation and survival in cardiac arrest. Circulation 104(21):2513–2516.

Shuster M, Keller JL. 1993. Effect of fire department first-responder automated defibrillation. Annals of Emergency Medicine 22(4):721–727.

Smith E, Singh T, Adirim T. 2001. Outstanding outreach: A prehospital notification system makes a difference for special needs children. Journal of Emergency Medical Services 26(5):48–55.

Snooks H, Williams S, Crouch R, Foster T, Hartley-Sharpe C, Dale J. 2002. NHS emergency response to 999 calls: Alternatives for cases that are neither life threatening nor serious. British Medical Journal 325(7359):330–333.

Todd KH, Heron SL, Thompson M, Dennis R, O’Connor J, Kellermann AL. 1999. Simple CPR: A randomized, controlled trial of video self-instructional cardiopulmonary resuscitation training in an African American church congregation. Annals of Emergency Medicine 34(6):730–737.

U.S. Bureau of the Census. 2004. Annual Estimates of the Population by Sex, Race and Hispanic or Latino Origin for the United States: April 1, 2000 to July 1, 2003. [Online]. Available: http://www.census.gov/popest/archives/2000s/vintage_2004/ [accessed March 2, 2006].

Wilber DQ. 2005, May 7. D.C. paramedic shortage causes concern. The Washington Post. P. B03.