1

Introduction

Emergency medical services (EMS) plays a vital role in the nation’s emergency and trauma care system, providing response and medical transport for millions of sick and injured Americans each year. Recent estimates indicate that more than 15,000 EMS systems and upwards of 800,000 EMS personnel (emergency medical technicians [EMTs] and paramedics) respond to more than 16 million transport calls annually (Mears, 2004; McCaig and Burt, 2005; Lindstrom, 2006). Through these encounters, prehospital EMS care is delivered directly to patients, in the locations where help is needed.

Prehospital EMS encompasses a range of related activities, including 9-1-1 dispatch, response to the scene by ambulance, treatment and triage by EMS personnel, and transport to a care facility via ground and/or air ambulance. Importantly, it also includes medical direction provided through preestablished medical protocols or a direct link to a hospital or physician. EMS may encompass multiple levels of medical response, depending on how the system is configured in a community. These may include EMS call takers and emergency medical dispatchers working in a 9-1-1 call center; first responders (often fire or police units); basic life support (BLS) and/or advanced life support (ALS) ground ambulances staffed by individuals with different levels of training, depending on the requirements of the state; and air medical EMS units, which are usually staffed by paramedics or critical care nurses, but may sometimes carry a physician. EMS represents the first stage in a full continuum of emergency care that also includes hospital emergency departments (EDs), trauma systems/centers, inpatient critical care services, and interfacility transport.

STRENGTHS OF THE CURRENT SYSTEM

The EMS system has a number of notable strengths. Prehospital EMS is far more sophisticated and far more capable than it was 40 years ago. The 9-1-1 emergency notification system is available to virtually all Americans and is regarded as highly responsive and reliable. The system enables rapid response to medical emergencies and facilitates crucial lifesaving care. In addition, the broad availability of cell phones has expanded 9-1-1 access to emergency and trauma scenes where no help was available before. The development of automatic crash notification technology, now becoming more widely available, has further improved emergency response, providing immediate and increasingly detailed crash information to dispatchers automatically, even before anyone on scene places a call.

In general, Americans have access to rapid ambulance response in emergency situations. While there are many glaring exceptions, first responders in urban and suburban areas are generally able to arrive on scene within minutes of notification, with ambulance crews close behind. Moreover, with greater emphasis now being placed on bystander care and prearrival instructions provided by dispatchers, care to patients can be initiated even more rapidly. In addition, air ambulance operations allow more advanced medical capacity to be delivered to patients directly and can often reduce transport times to medical facilities. In areas where trauma systems have developed, EMS and trauma providers are interdependent, working closely within an established protocol to help ensure that patients are transported to the most appropriate facility as quickly as possible.

EMS personnel form the backbone of the prehospital care system despite working under conditions that are stressful and at times dangerous. Many of them provide their services on a volunteer basis. The sophisticated equipment now at the disposal of many EMS providers, such as automated external defibrillators (AEDs) and 12-lead electrocardiographs (ECGs), as well as more effective medications, allow them to provide a much broader array of services than was available in years past.

PATIENT DEMOGRAPHICS

Of the 113.9 million ED visits that occurred in 2003, an estimated 14 percent were made by patients who arrived by ambulance. The most frequent complaints included chest pains, shortness of breath, stomach pain, injury from a motor vehicle crash or some type of accident, convulsions, and general weakness. The majority of visits were for illness (59.3 percent), whereas 40.7 percent were for injury, poisoning, or adverse effects of medical treatment (Burt et al., 2006). Prehospital cardiac arrests occur at a rate of 250,000 per year or more than 650 per day across the country, and these cases are frequently handled by EMS providers (Zheng et al., 2001). While

only 14 percent of ED visitors arrived by ambulance in 2003, 40 percent of hospital admissions from the ED in that year were transport patients. In general, transport patients have more complex medical conditions and require more care than walk-in patients. In 2003, an average of 6.5 different diagnostic tests and services were ordered or performed for transport cases—about 40 percent higher than the average for nontransport cases.

While transport patients tend to have more severe conditions than walk-in patients, a significant percentage of those treated by EMS personnel do not have life-threatening problems. Often these patients contact 9-1-1 because they are experiencing acute onset of conditions that cause alarming symptoms, and frequently substantial pain and anxiety. Over the last several years, EMS providers and researchers have acknowledged this situation and have had much greater interest in determining how best to care for these patients (Maio et al., 2002; Alonso-Serra et al., 2003).

A high proportion of transport patients are seniors. In 2003, less than 4 percent of children under age 15 were brought in to the ED by ambulance, but more than 40 percent of those aged 75 or older were transport patients (see Table 1-1). Because children make up a relatively small percentage of transports, it is a challenge to ensure that EMS personnel have the skills and equipment required to address their needs (e.g., properly sized equipment and knowledge of appropriate care procedures). However, the sizable number of elderly transport patients also presents significant challenges, in terms of both patient care (e.g., complications from chronic illness) and reimbursement (i.e., a greater percentage of payments made through Medicare, which does not cover all costs). With the aging of the baby boomers, even greater percentages of seniors are projected to require ambulance transport in the coming years.

TABLE 1-1 Proportion of Emergency Department Visits Made by Walk-in Versus Transport Patients, by Patient Age (United States, 2003)

AN EVOLVING AND EMERGING CRISIS

Many experts date the development of modern EMS systems in the United States back to the publication of the landmark report Accidental Death and Disability: The Neglected Disease of Modern Society (NAS and NRC, 1966). Following the publication of this report and subsequent congressional action, EMS systems began to develop rapidly across the country. However, this momentum was lost in 1981 when direct federal funding for the planning and development of EMS systems ended and was replaced by block grants to states. Over the past 25 years, EMS systems have developed haphazardly nationwide, regulated by state EMS offices that have been highly inconsistent in their level of sophistication and control. The result has been a fragmented and sometimes balkanized network of underfunded EMS systems that often lack strong quality controls, cannot or do not collect data to evaluate and improve system performance, fail to communicate effectively within and across jurisdictions, allocate limited resources inefficiently, and lack effective strategies and resources for recruiting and retaining personnel.

A significant lack of funding and infrastructure for EMS research has sharply limited studies of the safety and efficacy of many common EMS practices. Pressing questions remain regarding a number of central issues, such as the value of ALS services, the safety and efficacy of many common EMS procedures, the optimal approach to managing multisystem trauma, and the cost-effectiveness of public-access defibrillation programs. Barriers to data collection, a lack of standardized terms, and a limited pool of researchers trained and interested in EMS all pose significant challenges to research in the field. As a result, the prehospital emergency care system provides a stark example of how standards of care and clinical protocols can take root despite an almost total lack of evidence to support their use.

Because of this lack of supporting evidence, EMS systems often must operate blindly in addressing such questions as how available EMS personnel should be deployed, what services should be provided in the out-of-hospital setting, and what approach to organizing the EMS system is best. Multiple models of EMS organization have evolved over time, including fire department–based systems, hospital-based systems, and other public and private models. However, there is little research to demonstrate whether any one of these approaches is more effective than the others.

Within the last several years, complex problems facing the emergency care system have come into public view. Press coverage has highlighted instances of slow EMS response times, ambulance diversions, trauma center closures, and ground and air crashes during patient transport. This heightened public awareness of problems that have been building over time has made clear the need for a comprehensive review of the U.S. emergency care system. Although emergency care represents a vital component of the U.S.

health system, to date no such study of the system has been conducted. The events of September 11, 2001, and more recent disasters, such as Hurricane Katrina and the subway bombings in London and Madrid, have further raised awareness of the need for this type of study.

An assessment of the emergency care system in the United States is a logical extension of previous work conducted by the National Academy of Sciences (NAS), the National Research Council (NRC), and the Institute of Medicine (IOM). In addition to Accidental Death and Disability, other reports, such as Roles and Resources of Federal Agencies in Support of Comprehensive Emergency Medical Services (NAS and NRC, 1972) and Emergency Medical Services at Midpassage (NAS and NRC, 1978), have had a major impact in shaping the development of the emergency care system.

More recently, several IOM studies on injury and disability have emphasized the need for skilled emergency care to limit the adverse consequences of illness and injury (IOM, 1985). Additionally, the IOM produced a study of EMS systems for children (IOM, 1993) that generated unprecedented attention to the subject and has led to many improvements in the delivery of pediatric emergency care.

One way to assess the overall quality of EMS is to consider the six quality aims defined by the IOM in its seminal report Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century (IOM, 2001): health care should be safe, effective, patient-centered, timely, efficient, and equitable (see Box 1-1). While the evidence is limited, there are strong indications that the current EMS system fails the American public in significant ways along all of these dimensions of quality care.

Safety

Prehospital emergency care services are delivered in an uncertain, stressful environment where the need for haste and other potential distractions produce threats to patient care and safety. In addition, shift work and around-the-clock coverage contribute to fatigue among EMS providers (Fairbanks, 2004). Error rates for such procedures as endotracheal intubation are high, especially compared with the same procedures performed in a hospital setting (Katz and Falk, 2001; Wang et al., 2003; Jones et al., 2004).

In addition to these concerns regarding patient safety, there are concerns about the safety of EMS personnel. Working conditions for these personnel are physically demanding and often dangerous. Injury rates for EMS workers are high; back injuries are especially common, as are other “sprains, strains, and tears” (Maguire et al., 2005). EMS personnel are frequently exposed to the threat of violence and other unpredictable and

|

BOX 1-1 The Six Quality Aims of the Institute of Medicine’s Quality Chasm Report Health care should be:

SOURCE: IOM, 2001, pp. 5–6. |

uncontrolled situations (Franks et al., 2004). Moreover, they can be exposed to potentially infectious bodily fluids and airborne pathogens. In addition to these dangers, crashes involving ground ambulances are a major concern; according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 300 fatal crashes involving ambulances occurred in the United States between 1991 and 2000 (CDC, 2003).

Effectiveness

As noted above, there is very limited evidence about the effectiveness of many EMS interventions. Although there have been a small number of landmark studies in EMS, for the most part the knowledge base is quite limited. As a result, patients cannot be certain that they will receive the best possible care in their encounters with the EMS system. Questions related to core aspects of current clinical EMS practice remain unresolved, and EMS personnel must often rely on their best judgment in the absence of evidence. Not infrequently, treatments with established effectiveness and

safety profiles in hospital- or office-based settings are implemented in the out-of-hospital setting without adequate examination of patient outcomes (Gausche-Hill, 2000; Gausche et al., 2000).

Another example is the debate over whether EMS personnel should perform ALS procedures in the field, or rapid transport to definitive care is best (Wright and Klein, 2001). EMS responders who provide stabilization before the patient arrives at a critical care unit are sometimes subject to criticism because of a strongly held belief among many physicians that out-of-hospital stabilization only delays definitive treatment without adding value. However, there is little evidence that the prevailing “scoop and run” paradigm of EMS is optimal (Orr et al., 2006) except in certain circumstances, such as reducing time to reperfusion for heart attack patients (Waters et al., 2004).

In addition to the significant gaps in knowledge regarding appropriate treatments, there are important gaps in recording patient outcomes. Many cities do not track outcomes, so the performance of their EMS systems cannot be evaluated or benchmarked against that of the systems of other cities. The limited evidence that is available shows wide variation nationwide. For example, results of investigative research by USA Today indicate that the percentage of people suffering ventricular fibrillation who survive and are later discharged from the hospital with good brain function ranges from 3 to 45 percent depending on the municipality (Davis, 2003). This broad variation illustrates the tremendous challenge involved in making the EMS system overall more effective.

Recent EMS research has been able to contribute to the knowledge base regarding appropriate and effective EMS care. For example, the Ontario Prehospital Advanced Life Support study demonstrated that an optimized EMS system with rapid defibrillation capabilities may not benefit from the addition of ALS interventions. In addition, the Public Access Defibrillation trial found that providing AEDs in the community, along with adequate CPR training, can improve survival from cardiac arrest due to ventricular fibrillation. Studies have also shown that CPR involving only chest compressions can be effective, and a number of large U.S. cities have changed the way their 9-1-1 dispatchers provide CPR prearrival instructions as a result.

Patient-Centeredness

EMS systems are geared toward meeting the needs of patients with specific acute conditions, such as heart attack, stroke, and injuries resulting from automobile crashes and other types of accidents. However, they are not always well equipped to meet the needs of special populations or of patients with less acute medical conditions. For example, language bar-

riers pose significant problems, both for EMS personnel arriving on scene and for 9-1-1 communicators and emergency medical dispatchers. As a result, patients may be unable to convey their situation adequately to these emergency responders. In addition, EMS providers often struggle to address the challenges presented by severely obese patients (Greenwood, 2004). Standard-issue equipment may be incapable of bearing the weight of these patients, and responses may require multiple personnel.

Children present special challenges to EMS personnel as well. Studies indicate that many prehospital providers are less comfortable caring for pediatric patients, particularly infants, than for adult patients. For example, paramedics have reported being very comfortable about terminating CPR on adults, but very uncomfortable about doing so on children (Hall et al., 2004). A study that looked at job satisfaction among paramedics found that they view pediatric calls as among the most stressful because of the low volume of such cases they typically encounter (Federiuk et al., 1993). For these and other special populations, EMS systems often struggle to provide adequate care.

In addition, while EMS systems are frequently organized to address major traumas and serious medical emergencies, the overwhelming majority of EMS patients have relatively minor complaints. Focusing on this broader spectrum of complaints could make the system more patient-centered.

Timeliness

Response times vary widely depending on the location where an incident occurs. Across the large, sparsely populated terrain of rural areas, EMS response times—from the medically instigating event to arrival at the hospital—are significantly increased compared with those in urban areas. These prolonged response times occur at each step in EMS activation and response, including time to EMS notification, time from EMS notification to arrival at the scene, and time from EMS arrival on the scene to hospital arrival.

Even across cities, however, there are substantial differences in EMS response times (Davis et al., 2003). As a result, a person who suffers a traumatic injury or acute illness in one city may be far more likely to die than the same person in another city. One important factor contributing to slow response times in some areas is the frequency of ED crowding and ambulance diversion. When EDs are crowded, as is frequently the case, EMS personnel wait with the transported patient until space becomes available in the ED. This wait reduces the time during which the ambulance could be servicing the community, thus increasing response times. When hospitals go on diversion status, ambulances may have to drive longer distances and take patients to less appropriate facilities. Again, definitive patient care is

delayed. It is estimated that 501,000 ambulances were diverted in 2003 (Burt et al., 2006).

Efficiency

The health sector in general and emergency and trauma care services in particular lag behind other industries in adopting engineering principles and information technologies that can improve process management, lower costs, and enhance quality. Inefficiency in EMS care takes various forms:

-

Little is known about the cost-effectiveness of EMS interventions. As with EMS research in general, sparse information exists to help guide the field in this area. Reimbursement policies and federal regulations also contribute to inefficiencies. In many cases, providers are not reimbursed unless they transport a patient to the ED, even though it may be more efficient and just as effective to treat the patient on site.

-

Services are often poorly coordinated. In some situations, for example, multiple vehicles respond to a single small event. Significant problems are often encountered near municipal, county, and state border areas. When a street delineates the boundary between two city or county jurisdictions, responsibility for care—as well as the protocols and procedures employed—depends on the side of the street on which the incident occurred.

-

The Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act may require that certain EMS agencies perform a medical screening exam when in fact a patient should be transported immediately to a trauma center for definitive care.

-

Outdated and poorly planned technologies also contribute to inefficiencies. For example, many of the 9-1-1 calls placed today are from cellular phones, but dispatchers often lack the capability to trace the location of such callers. In the event of a disaster, most EMS communications systems are not compatible with those of other responders, such as police and fire departments.

Equity

Disparities in access to EMS systems are evident, particularly between urban and rural communities. For example, there are still small pockets of the country that do not offer even basic 9-1-1 coverage, and these are located exclusively in rural or frontier areas. Moreover, only 45 percent of counties nationwide have the more advanced 9-1-1 systems that can track the location of cellular callers, even though this information can be vitally important in responding to various emergency situations.

Ground and air ambulance coverage is also uneven across the country.

Because of the reduced call volume in rural areas, fewer ground ambulances are available to cover the wide expanses involved. In addition, the Atlas and Database of Air Medical Services indicates that many rural areas still do not have sufficient access to air ambulance providers. Given the inherent difficulty of providing timely care in remote areas, crash fatalities in these locales are more frequent. In 2001, 61 percent of all crash fatalities occurred along rural roads, even though only 39 percent of vehicle-miles were traveled in such areas (Flanigan et al., 2005).

OVERVIEW OF THE STUDY

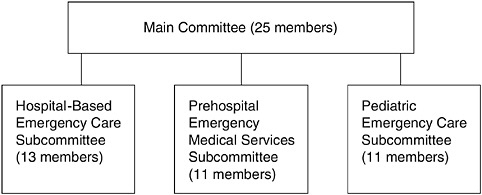

The IOM’s study of the Future of Emergency Care in the United States Health System was initiated in September 2003. Support for the study was provided by the Josiah Macy, Jr. Foundation, the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA), the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), and CDC. Given the broad scope of the effort, the work was divided among a main committee and three subcommittees (see Figure 1-1).

The main committee provided primary direction for the study and was responsible for investigating the systemwide issues that span the continuum of emergency care in the United States. The 13-member subcommittee on hospital-based emergency care was created to examine issues specific to the ED setting, including workforce supply, patient flow, use of information technologies, and disaster preparedness and surge capacity. The 11-member subcommittee on prehospital EMS was created to assess the current organization, delivery, and financing of EMS and EMS systems and to advance NHTSA’s Emergency Medical Services Agenda for the Future (NHTSA, 1996). Finally, the 11-member subcommittee on pediatric emer-

FIGURE 1-1 Committee and subcommittee structure.

gency care was created to examine the unique issues associated with the provision of emergency services to children and adolescents.

A total of 40 individuals served across all four committees (see Appendix A).1 Subcommittee members were responsible for developing recommendations in their respective areas for presentation to the main committee, which had sign-off authority on all of the study recommendations. The subcommittees worked collaboratively, and considerable cross-fertilization occurred among them and their members.

The main committee and subcommittees each met separately four times between February 2004 and October 2005; a combined meeting for all members was held in March 2005. The study also benefited from the contributions of a wide range of experts who made presentations to the committee, wrote commissioned papers, and met with the committee members and/or IOM project staff on an informal basis. A report was produced in each of the three areas addressed by the subcommittees. The charge to the EMS subcommittee, which guided the development of the present report, is shown in Box 1-2.

KEY TERMS AND DEFINITIONS

To ensure clarity and consistency, the following terminology is used throughout this study’s three reports. Emergency medical services, or EMS, denotes prehospital and out-of-hospital emergency medical services, including 9-1-1 and dispatch, emergency medical response, field triage and stabilization, and transport by ambulance or helicopter to a hospital and between facilities. EMS system refers to the organized delivery system for EMS within a specified geographic area—local, regional, state, or national—as indicated by the context.

Emergency care is broader than EMS and encompasses the full continuum of services involved in emergency medical care, including EMS, hospital-based ED and trauma care, specialty care, bystander care, and injury prevention. Emergency care system refers to the organized delivery system for emergency care within a specified geographic area.

Trauma care is the care received by a victim of trauma in any setting, while a trauma center is a hospital specifically designated to provide trauma care; some trauma care is provided in settings other than a trauma center. Trauma system refers to the organized delivery system for trauma care at the local, regional, state, or national level. Because trauma care is a component of emergency care, it is always assumed to be encompassed by the

|

BOX 1-2 Charge to the EMS Subcommittee The overall objectives of this study are to: (1) examine the emergency care system in the United States; (2) explore its strengths, limitations, and future challenges; (3) describe a desired vision of the emergency care system; and (4) recommend strategies required to achieve that vision. Within this context, the Subcommittee on Prehospital Emergency Medical Services (EMS) will examine prehospital EMS and include an assessment of the current organization, delivery, and financing of EMS and EMS systems, and assess progress toward the Emergency Medical Services Agenda for the Future. The subcommittee will consider a wide range of issues, including:

|

terms hospital-based or inpatient emergency care, emergency care system, and regional emergency care system.

The term region is used throughout the report to mean a broad geographic area, typically larger than a municipality and smaller than a state. However, a region in some cases encompasses an area that overlaps two states.

ORGANIZATION OF THIS REPORT

Chapter 2 highlights important developments in the history of EMS and describes the current state of the industry. It reviews the EMS delivery models now in operation nationwide and details the key challenges to the delivery of high-quality EMS care that meets the six aims outlined in Box 1-1. The chapter examines the gains achieved through previous reform efforts, as well as some of the key barriers to their full adoption.

Chapter 3 charts a new direction for the future of emergency care, one

in which all communities are served by well-planned and highly coordinated emergency care systems that are accountable for their performance. The chapter establishes a vision in which the various components of the emergency and trauma care system are connected through improved communications networks and organized through a regionalized system of care. A national demonstration program is proposed in which states and communities would be able to create and test new models for the delivery of emergency and trauma care services.

Chapter 4 examines the EMS workforce, including EMTs and paramedics, volunteers, emergency medical dispatchers, and EMS physician medical directors. The chapter details the current education and training standards for EMS personnel and proposes the establishment of a national certification requirement. It also proposes the transition to a common scope of practice across states. In addition, the chapter addresses issues surrounding recruitment and retention of EMS personnel, including worker safety and pay.

Chapter 5 examines an array of issues relating to infrastructure and technologies employed by the EMS system, including 9-1-1, enhanced 9-1-1, and next-generation 9-1-1 capabilities; automatic crash notification systems; equipment-related issues, such as ambulance design and safety; and air medical capacity and operations. The chapter also describes the technology upgrades required to achieve the goal of interoperable communications among various public safety responders (EMS, fire, police), between EMS and medical facilities (including voice and video communications and electronic health records), and throughout the EMS system overall.

Chapter 6 reviews the steps needed to develop an emergency care system capable of meeting the challenge of a major terrorist event, unintentional man-made disaster, natural disaster, or other public health crisis. The chapter demonstrates that having an emergency care system that functions efficiently and effectively on a daily basis is fundamental to having a system that is ready to handle larger public health and public safety crises. In addition, the chapter describes EMS equipment and training needs, including greater distribution of personal protective equipment and development of more effective communications systems, as well as improved hospital surge capacity.

Chapter 7 examines the research required to support improvements in EMS. It reviews the need for data collection and outcome assessments and the mechanisms required to generate these data. In addition, the chapter describes enhanced research strategies, such as multicenter collaborations and support for talented investigators. The chapter also describes current data work now being conducted (e.g., the National EMS Information System [NEMSIS]) and steps required to change the regulatory environment (i.e., the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act) to make outcome assessments possible.

Finally, following the chapters are a number of appendixes:

-

Appendix A contains a chart listing all committee and subcommittee members.

-

Appendix B provides biographical information on members of the main committee and the Subcommittee on Prehospital EMS.

-

Appendix C lists the presentations made during public sessions of the committee meetings.

-

Appendix D lists the research papers commissioned by the committee.

-

Appendix E contains the recommendations from all three reports in the Future of Emergency Care series and indicates the entities with primary responsibility for implementation of each recommendation.

REFERENCES

Alonso-Serra HM, Wesley K, National Association of EMS Physicians Standards and Clinical Practices Committee. 2003. Prehospital pain management. Prehospital Emergency Care 7(4):482–488.

Burt CW, McCaig LF, Valverde RH. 2006. Analysis of Ambulance Transports and Diversions among U.S. Emergency Departments. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics.

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2003. Ambulance crash-related injuries among emergency medical services workers––United States, 1991–2002. Morbidity & Mortality Weekly Report 52(8):154–156.

Davis R. 2003, July. Many lives are lost across USA because emergency services fail. USA Today. P. 1A.

Davis R, Coddington R, West J. 2003. The State of Emergency Medical Services across the USA: How 50 Major Cities Stack Up. [Online]. Available: http://www.usatoday.com/graphics/life/gra/ems/flash.htm [accessed January 1, 2006].

Fairbanks T. 2004. Human Factors & Patient Safety in Emergency Medical Services. Science Forum on Patient Safety and Human Factors Research.

Federiuk CS, O’Brien K, Jui J, Schmidt TA. 1993. Job satisfaction of paramedics: The effects of gender and type of agency of employment. Annals of Emergency Medicine 22(4):657–662.

Flanigan M, Blatt A, Lombardo L, Mancuso D, Miller M, Wiles D, Pirson H, Hwang J, Thill J, Majka K. 2005. Assessment of air medical coverage using the atlas and database of air medical services and correlations with reduced highway fatality rates. Air Medical Journal 24(4):151–163.

Franks PE, Kocher N, Chapman S. 2004. Emergency Medical Technicians and Paramedics in California University of California. San Francisco, CA: San Francisco Center for the Health Professions.

Gausche M, Lewis RJ, Stratton SJ, Haynes BE, Gunter CS, Goodrich SM, Poore PD, McCollough MD, Henderson DP, Pratt FD, Seidel JS. 2000. Effect of out-of-hospital pediatric endotracheal intubation on survival and neurologic outcome: A controlled clinical trial. Journal of the American Medical Association 283(6):783–790.

Gausche-Hill M. 2000. Pediatric continuing education for out-of-hospital providers: Is it time to mandate review of pediatric knowledge and skills? Annals of Emergency Medicine 36(1):72–74.

Greenwood MD. 2004. Weighty matters: Transporting obese patients. Journal of Emergency Medical Services 33(10).

Hall WL II, Myers JH, Pepe PE, Larkin GL, Sirbaugh PE, Persse DE. 2004. The perspective of paramedics about on-scene termination of resuscitation efforts for pediatric patients. Resuscitation 60(2):175–187.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 1985. Injury in America: A Continuing Health Problem. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

IOM. 1993. Emergency Medical Services for Children. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

IOM. 2001. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Jones JH, Murphy MP, Dickson RL, Somerville GG, Brizendine EJ. 2004. Emergency physician-verified out-of-hospital intubation: Miss rates by paramedics. Academic Emergency Medicine 11(6):707–709.

Katz SH, Falk JL. 2001. Misplaced endotracheal tubes by paramedics in an urban emergency medical services system. Annals of Emergency Medicine 37(1):32–37.

Lindstrom AM. 2006. 2006 JEMS platinum resource guide. Journal of Emergency Medical Services 31(1):42–56, 101.

Maguire BJ, Hunting KL, Guidotti TL, Smith GS. 2005. Occupational injuries among emergency medical services personnel. Prehospital Emergency Care 9(4):405–411.

Maio RF, Garrison HG, Spaite DW, Desmond JS, Gregor MA, Stiell IG, Cayten CG, Chew JL Jr, Mackenzie EJ, Miller DR, O’Malley PJ. 2002. Emergency Medical Services Outcomes Project (EMSOP) IV: Pain measurement in out-of-hospital outcomes research. Annals of Emergency Medicine 40(2):172–179.

McCaig LF, Burt CW. 2005. National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2003 Emergency Department Summary. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics.

Mears G. 2004. 2003 Survey and Analysis of EMS Scope of Practice and Practice Settings Impacting EMS Services in Rural America: Executive Brief and Recommendations. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Department of Emergency Medicine.

NAS, NRC (National Academy of Sciences, National Research Council). 1966. Accidental Death and Disability: The Neglected Disease of Modern Society. Washington, DC: NAS.

NAS, NRC. 1972. Roles and Resources of Federal Agencies in Support of Comprehensive Emergency Medical Services. Washington, DC: NAS.

NAS, NRC. 1978. Emergency Medical Services at Midpassage. Washington, DC: NAS.

NHTSA (National Highway Traffic Safety Administration). 1996. Emergency Medical Services Agenda for the Future. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Transportation.

Orr RA, Han YY, Roth K. 2006. Pediatric transport: Shifting the paradigm to improve patient outcome. In: Fuhrman B, Zimmerman J, eds. Pediatric Critical Care (3rd edition). Philadelphia, PA: Mosby, Elsevier Science Health. Pp. 141–150.

Wang HE, Kupas DF, Paris PM, Bates RR, Costantino JP, Yealy DM. 2003. Multivariate predictors of failed prehospital endotracheal intubation. Academic Emergency Medicine 10(7):717–724.

Waters RE II, Singh KP, Roe MT, Lotfi M, Sketch MH Jr, Mahaffey KW, Newby LK, Alexander JH, Harrington RA, Califf RM, Granger CB. 2004. Rationale and strategies for implementing community-based transfer protocols for primary percutaneous coronary intervention for acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 43(12):2153–2159.