2

History and Current State of EMS

Across the country, emergency medical services (EMS) agencies face numerous challenges with regard to their funding, management, workforce, infrastructure, and research base. Though the modern EMS system was instituted and funded in large part by the federal government through the Highway Safety Act of 1966 and the EMS Act of 1973, federal support for EMS agencies declined precipitously in the early 1980s. Since that time, states and localities have taken more prominent roles in financing and designing EMS programs. The result has been considerable fragmentation of EMS care and wide variability in the type of care that is offered from state to state and region to region. This chapter traces the development of the modern EMS system and describes the current state of EMS at the federal, state, and local levels.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF EMS

EMS dates back centuries and has seen rapid advances during times of war. At least as far back as the Greek and Roman eras, chariots were used to remove injured soldiers from the battlefield. In the late 15th century, Ferdinand and Isabella of Spain commissioned surgical and medical supplies to be provided to troops in special tents called ambulancias. During the French Revolution in 1794, Baron Dominique-Jean Larrey recognized that leaving wounded soldiers on the battlefield for days without treatment dramatically increased morbidity and mortality, weakening the fighting strength of the army. He instituted a system in which trained medical per-

sonnel initiated treatment and transported the wounded to field hospitals (Pozner et al., 2004).

This model was emulated by Americans during the Civil War. General Jonathan Letterman, a Union military surgeon, created the first organized system in the United States to treat and transport injured patients. Based on this experience, the first civilian-run, hospital-based ambulance service began in Cincinnati in 1865. The first municipally based EMS began in New York City in 1869 (NHTSA, 1996).

In 1910, the American Red Cross began providing first-aid training programs across the country, initiating an organized effort to improve civilian bystander care. During World Wars I and II, further advances were made in EMS, although typically these were not replicated in the civilian setting until much later (Pozner et al., 2004). Following World War II, city EMS activities were for the most part run by municipal hospitals and fire departments. In smaller communities, funeral home hearses often served as ambulances because they were the only vehicle capable of transporting patients quickly in stretchers. With the advent of federal involvement in EMS in the early 1970s and the articulation of standards at the state and regional levels, these EMS providers were gradually replaced by others, including third-service providers, fire departments, rescue squads, and private ambulances (NHTSA, 1996).

By the late 1950s, prehospital emergency care in the United States was still little more than first aid (IOM, 1993). Around that time, however, advances in medical care began to spur the rapid development of modern EMS. While the first recorded use of mouth-to-mouth ventilation had been in 1732, it was not until 1958 that Dr. Peter Safar demonstrated it to be superior to other modes of manual ventilation. In 1960, cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) was shown to be efficacious. These two clinical advances led to the realization that rapid response of trained community members to cardiac emergencies could improve outcomes. The introduction of CPR and the development of portable external defibrillators in the 1960s provided the foundation for advanced cardiac life support (ACLS) that fueled much of the development of EMS systems in subsequent years.

In 1965, the President’s Committee for Traffic Safety published the report Health, Medical Care and Transportation of the Injured. The report recommended a national program to reduce highway deaths and injuries. The following year, the National Academy of Sciences (NAS) and National Research Council (NRC) released Accidental Death and Disability: The Neglected Disease of Modern Society (NAS/NRC, 1966). That report emphasized that the health care system needed to address injuries, which at the time were the leading cause of death for those aged 1–37. It noted that in most cases, ambulances were inappropriately designed, ill-equipped, and often staffed with inadequately trained personnel. For example, the report

called attention to the fact that at least 50 percent of ambulance services nationwide were being provided by morticians. The report contained a total of 29 recommendations, 11 of which applied directly to prehospital EMS (Delbridge et al., 1998). These included recommendations to (1) develop federal standards for ambulances (design, construction, equipment, supplies, personnel training and supervision); (2) adopt state ambulance regulations; (3) ensure provision of ambulance services applicable to the conditions of the local government; (4) initiate pilot programs to evaluate automotive and helicopter ambulance services in sparsely populated areas; (5) assign radio channels and equipment suitable for voice communications between ambulances and emergency departments (EDs) and other health-related agencies; and (6) develop a single nationwide telephone number for summoning an ambulance. The report also laid out a vision for the establishment of trauma systems as we know them today.

In addition to the momentum that had been provided by the President’s Commission, support for the NAS/NRC report was fueled by surgeons with military experience in Korea and World War II who recognized that the trauma care available to soldiers overseas was better than the care available in local communities. In 1966, Congress passed the Highway Safety Act, which led to the formation of the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) within the Department of Transportation (DOT). NHTSA was given authority to fund improvements in EMS. Among those improvements, NHTSA developed a national EMS education curriculum and model state EMS legislation. NHTSA’s 70-hour basic EMT curriculum became the first standard EMT training in the United States. The department developed more extensive advanced life support (ALS) training several years later. Also as part of the 1966 act, DOT offered grant funding to states with the goal of improving the provision of EMS.

1970s: Rapid Expansion of Regional EMS Systems

In the early 1970s, additional research and policy planning focused on the unmet needs of EMS. In 1972, the NAS/NRC released another report on EMS entitled Roles and Resources of Federal Agencies in Support of Comprehensive Emergency Medical Services (NAS and NRC, 1972). The report expressed concern that the federal effort to upgrade EMS had not kept pace with what was needed. It urged integration of all federal EMS efforts into the Department of Health, Education and Welfare (DHEW, which later became the Department of Health and Human Services [DHHS]). The report also stated that the focal point for local EMS should be at the state rather than the federal level, and that all efforts should be coordinated through regional programs.

In 1973, Congress enacted the EMS Systems Act, which created a new grant program to further the development of regional EMS systems. The intent of the law was to improve and coordinate care throughout the country through the creation of a categorical grant program run by the new Division of Emergency Medical Services within DHEW. This program became a decisive factor in the nationwide development of regional EMS systems. Millions of dollars were earmarked for EMS training, equipment, and research. In total, more than $300 million was appropriated for EMS feasibility studies, planning, operations, expansion and improvement, and research. (In 2004 dollars, this investment equates to $1.3 billion.) Also, in 1974 The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation appropriated $15 million to fund 44 regional EMS projects ($64 million in 2004 dollars). To this day, this remains the largest private grant for EMS system development ever awarded.

An important feature of the grant program was its emphasis on the need for effective planning at the state, regional, and local levels to ensure coordination of prehospital and hospital emergency care. Across the country, state EMS offices began to emerge. With the federal support, states established a total of about 300 EMS regions—most covering several counties—each eligible to receive up to 5 years of funding (NHTSA, 1996). The law also identified 15 essential elements that should be included in an EMS system: manpower, training, communications, transportation, facilities, critical care units, public safety agencies, consumer participation, access to care, patient transfer, coordinated patient record keeping, public information and education, review and evaluation, disaster plan, and mutual aid. The EMS Systems Act helped guide the development of models of service delivery; informed system functions such as medical direction, triage protocols, communication, and quality assurance; and set the tone of the EMS system’s interaction with the larger health care and public health systems. While the act identified ideal components of an EMS system from the federal government’s perspective, however, the organization of systems on the ground, including their scope of practice and overall structure, was fundamentally driven by local needs, characteristics, and concerns. A patchwork quilt of systems began to emerge.

A 1978 report by the NAS/NRC, Emergency Medical Services at Mid-passage, expressed criticism of DHEW and focused on the coordination problem between DOT and DHEW at the federal level (NAS and NRC, 1978). The report criticized the conflicting education standards developed by the two departments and recommended more research and evaluation of EMS system development. By 1981, an agreement between DOT and DHEW to coordinate efforts had been canceled, and the EMS program and DHEW grants had been eliminated.

1980s: Withdrawal of Federal Support and Leadership in EMS

In 1981, the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act (OBRA) eliminated the categorical federal funding to states established by the 1973 EMS Systems Act in favor of block grants to states for preventive health and health services. This change shifted responsibility for EMS from the federal to the state level. Once states had greater discretion regarding the use of funds, most chose to spend the money in areas of need other than EMS. Thus the immediate impact of the shift to block grants was a sharp decrease in total funding for EMS (U.S. Congress, Office of Technology Assessment, 1989). Moreover, states were left to develop their systems in greater isolation. Some increased their involvement in EMS, but others chose to cede more authority to cities and counties. Political, geographic, and fiscal disparities contributed to fragmented and diverse development of EMS systems at the local level. In addition, a lack of objective scientific evidence regarding the best models for EMS organization and delivery left many systems in the dark regarding appropriate steps to take.

The structure provided to local EMS systems by state governments varied. Lead state EMS agencies remained in all states, but with varying degrees of authority and funding. Maryland, for example, chose to maintain an active role and retained significant authority at the state level. The Maryland Institute for Emergency Medical Services Systems was established in 1972 and continued to take a strong leadership role in subsequent years. The state elected to provide emergency air and ground transportation as a public service and created a sophisticated trauma system that designates trauma centers on the basis of compliance with standards and demonstrated need (IOM, 1993).

By contrast, California and many other states elected to take a less active role. By default as much as by design, regional and county EMS systems took the lead in designing and managing their EMS programs. California state government maintained responsibility for such issues as investigating EMS system complaints and setting EMS training standards, but otherwise had a diminished role in the overall direction of EMS systems. During the 1980s, some states maintained vestiges of the regional systems that were developed in the 1970s, but other systems were fractured along smaller and smaller local lines. The result was even greater diversity among systems.

In the early to mid-1980s, the role of voluntary national EMS organizations increased. These included the National Association of State EMS Officials (NASEMSO, formerly the National Association of State EMS Directors [NASEMSD]), the National Association of Emergency Medical Technicians (NAEMT), the National Association of EMS Physicians (NAEMSP), the American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma (ACS COT), and the American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) EMS Committee. In 1984, the Emergency Medical Services for Children (EMS-C) program was

established at the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) within DHHS.

In 1985, the NRC report Injury in America: A Continuing Health Problem described the limited progress that had been made in addressing the problem of accidental death and disability (IOM, 1985). The report described the need for a federal agency to focus on injuries as a public health problem. In response, an injury program was established at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) that approached injury prevention and control from a public health perspective. This program was later elevated to the status of a center at CDC—the National Center for Injury Prevention and Control (NCIPC).

During this period, rural EMS development lagged behind. The loss of federal funding and the limited financial resources available in states with large rural populations exacerbated this problem. In 1989, the Office of Technology Assessment released a report detailing the challenges faced by rural EMS (U.S. Congress, Office of Technology Assessment, 1989) (see the discussion of rural EMS below).

NHTSA implemented a statewide EMS technical assessment program in 1988. During these assessments, statewide EMS systems are evaluated on the basis of 10 essential components: regulation and policy, resource management, human resources and training, transportation, facilities, communications, public information and education, medical direction, trauma systems, and evaluation.

1990s to the Present: EMS—Looking Toward the Future

In 1995, through the urging of then NHTSA Administrator Ricardo Martinez, NHTSA and HRSA commissioned a strategic plan for the future EMS system. The resulting report, Emergency Medical Services Agenda for the Future (NHTSA, 1996), outlined a vision of an EMS system that is integrated with the health care system, proactive in providing community health, and adequately funded and accessible (see Table 2-1).

TABLE 2-1 New Vision for the Role of Emergency Medical Services

|

EMS Today (1996) |

EMS Tomorrow |

|

Isolated from other health services Reacts to acute illness and injury Financed for service to individuals Access through fixed-point phone |

Integrated with the health care system Acts to promote community health Funded for service to the community Supports fixed and mobile phones |

|

SOURCE: Martinez, 1998. |

|

In 1997, NHTSA gathered members of the EMS community to develop an implementation guide for making the recommendations in Agenda for the Future a reality. The implementation guide focused on three strategies: improving linkages between EMS and other components of the health care system, creating a strong infrastructure, and developing new tools and resources to improve the effectiveness of EMS.

Agenda for the Future, now a decade old, has been effective in drawing attention to EMS and placing a spotlight on the vital role played by EMS within the emergency and trauma care system. Several of the goals it set forth, however, have not yet been realized. Its vision, such as placing a focus on the care provided to entire communities rather than individuals and thinking proactively rather than reactively, still represents a significant conceptual leap for most EMS systems. The types of changes envisioned by the Agenda are discussed in the relevant context in the chapters that follow.

More recently, in 2001, the U.S. General Accounting Office (GAO) released a comprehensive study of local EMS system needs and of the state regulatory agencies responsible for improving EMS outcomes. The report characterized the needs as substantial and wide-ranging, and grouped the problems identified under four categories: personnel, training, equipment, and medical direction. The report noted that the extent of local needs was difficult to determine since little standard and quantifiable information exists for use in comparing performance across systems. The report also noted that most of the available information is localized and anecdotal (GAO, 2001b).

The terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, focused attention on the heroism of public safety personnel (fire, police, and EMS), but also exposed many of the technical and logistical challenges that confront the nation’s public safety systems. Communications capabilities were shown to be grossly deficient among the units that responded to the World Trade Center attacks, and a lack of interoperability and inadequate communications with rescuers within the towers probably contributed to the deaths of many rescue personnel (National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States, 2004). In the aftermath of the disaster, the federal government took a number of steps to improve response capabilities, including development of the National Response Plan and the National Incident Management System (NIMS) (discussed in Chapter 6).

Boxes 2-1 and 2-2 detail the development and recent experience of EMS systems in two U.S. cities.

THE TROUBLED STATE OF EMS

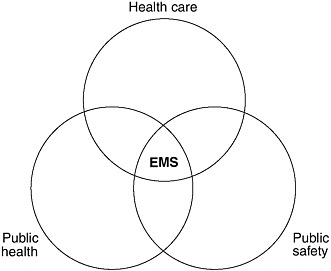

EMS operates at the intersection of health care, public health, and public safety and therefore has overlapping roles and responsibilities (see

|

BOX 2-1 Seattle, Washington Thirty years ago, Seattle had no organized EMS system and no paramedics. Several progressive individuals developed the concept that firefighters could be taught some of the medical skills that were normally reserved for physicians acting within a hospital. The goal was to provide these services at the earliest point of illness or injury. In 1970, the Seattle Fire Department, in cooperation with a small group of physicians at HarborviewMedical Center and the University of Washington, trained the first class of firefighters as paramedics. With strong community support supplemented by grants from the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, paramedic programs flourished in subsequent years. Research, much of it conducted within the Seattle “Medic One” EMS system, has shown that paramedics can provide high-quality care to patients outside of the hospital. The prehospital emergency medical care system pioneered in Seattle has become famous around the world and remains a model that many others attempt to emulate. Further, Seattle has taken its unique approach to its citizens. In 1998, the Washington State Legislature enacted a lawto facilitate the implementation of and compliance with a citizen defibrillation program. This city leads the nation in providing early care for victims of cardiac arrest as a result of the active involvement and training of civilians within the community. Citizens in Seattle are trained to recognize when a fellow citizen needs medical care, activate the 9-1-1 system, and help the victim until the EMS unit arrives. Seattle’s Medic One system exemplifies what can be achieved with political leadership, strong and sustained physician medical direction, community support, and data-driven decision making. |

Figure 2-1). Often, local EMS systems are not well integrated with any of these groups and therefore receive inadequate support from each of them. As a result, EMS has a foot in many doors, but no clear home.

Prehospital EMS faces a number of special challenges. First and foremost, EMS systems throughout the country are often highly fragmented. Although they are frequently required to work side by side, turf wars between EMS and fire personnel are not uncommon (Davis, 2003a, 2004). In addition, as noted above, the events of September 11, 2001, demonstrated that public safety agencies (including fire, police, emergency management, and EMS) often use incompatible equipment and are unable to communicate with each other during emergencies. Many of these problems are

magnified when incidents cross jurisdictional lines. Significant problems are often encountered near municipal, county, and state borders. Where a street delineates the boundary between two city or county jurisdictions, responsibility for care—as well as the protocols and procedures employed—depends on the side of the street on which the incident occurred. One county in Michigan has 18 different EMS systems with a range of service models and protocols. In addition, EMS providers have found that coordinating services across state lines is particularly challenging.

In addition, coordination between EMS and hospitals is often inadequate. While hospital ED staff often provide direct, on-line medical direction to EMS personnel during transport, time pressures, competing demands, and a lack of trust can at times hinder these interactions. In addition, cultural differences between EMS and hospital staff can impede the exchange of information. Upon arrival at the hospital, busy ED staff who are strug-

|

BOX 2-2 San Francisco, California Prior to 1997, San Francisco’s EMS system fell under the jurisdiction of the public health department, with the fire department providing first-responder support. During the late 1990s and early 2000s, a seven-phase merger process was initiated to place EMS under the jurisdiction of the fire department. However, this process experienced difficulties from the beginning and later resulted in a partial separation. The merger called for the cross-training of EMS personnel and firefighters, the placement of paramedics on city fire trucks, and institution of a “one and one” response program, with ambulances staffed by one paramedic and one EMT. However, the cross-training of firefighters as paramedics was delayed because of lengthy union negotiations. EMS workload constraints delayed EMTs’ fire-suppression cross-training. This in turn delayed the changes in personnel configuration. In addition, a requirement that EMS personnel work 24-hour shifts rankled paramedics and raised concerns about the impact on patient care. These and other issues revealed a clash between the firefighting and EMS cultures and raised questions about the advisability of the merger. An audit later determined that, despite the increased resources devoted by the fire department to EMS during the first 4 years of the merger, average response times had increased (City and County of San Francisco, Office of the Budget Analyst, 2002). The city later instituted a newplan in which a lower-paid group of paramedics and EMTs was hired and located outside of fire stations, partially ending the merger attempt. |

FIGURE 2-1 The overlapping roles and responsibilities of EMS.

SOURCE: NHTSA, 1996.

gling to manage a very crowded ED often greet arriving EMS units with, at best, a lack of enthusiasm. As a result, clinically important information is sometimes lost in patient handoffs between EMS and hospital staff.

Second, there is little doubt that ED crowding has had a very adverse impact on prehospital care. When an ED is crowded, ED staff may be unable to find the physical space needed to off-load patients. Under these circumstances, EMS units may be stuck in the ED for prolonged periods of time, leaving them out of service for other emergency calls. In addition, ED diversion has become commonplace in many major cities, further hindering the performance of EMS. In major metropolitan areas, it is not uncommon for all of the city’s trauma centers to request ambulance diversion at the same time. When hospital EDs go on diversion status, ambulances may have to drive longer distances and take patients to less appropriate facilities (GAO, 2003). Fully 45 percent of EDs reported going on diversion at some point in 2003, and the problem was especially pronounced in urban areas. Overall, it is estimated that 501,000 ambulances were diverted during that year (Burt et al., 2006).

Although it is likely that ambulance diversions endanger patients, there are no data directly linking ambulance diversions with higher mortality rates. No agency has sponsored a systematic study to examine this question, and fears of legal liability inhibit candid disclosure of adverse events (IOM, 2000). However, a study by the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO, 2002) revealed that more than

half of all “sentinel” ED events—defined as “an unexpected occurrence involving death or serious physical or psychological injury, or risk thereof”—were caused by delayed treatment. While this study was not centered on ambulance diversion, its findings are consistent with the argument that delays in treatment resulting from diversion can have deleterious effects on patients.

Third, the cost of maintaining an EMS system in a state of readiness is extremely high, and it is rarely compensated. The EMS reimbursement model used by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and emulated by many payers reimburses on the basis of transport to a medical facility. This model ignores the increasingly sophisticated care provided by EMS personnel, as well as the growing proportion of elderly patients with multiple chronic conditions who frequently utilize EMS. Medicaid typically pays a fixed rate—as low as $25 in some states—for an EMS transport, regardless of the complexity of the case or the resources utilized. The fact that payers generally withhold reimbursement in cases where transport is not provided is a major impediment to the implementation of processes that allow EMS to “treat and release,” to transport patients directly to a dialysis unit or another appropriate site, or to terminate unsuccessful cardiac resuscitation in the field. In addition, many systems of all types provide both 9-1-1 call services and medical transportation. To make up for funding shortfalls, these systems often offset the cost of the former services with revenues from the latter.

EMS is widely viewed as an essential public service, but it has not been supported through effective federal and state leadership and sustainable funding strategies. Unlike other such services—electricity, highways, airports, and telephone service, for example—all of which were created and are actively maintained through major national infrastructure investments, access to timely and high-quality emergency and trauma care has largely been relegated to local and state initiatives. As a result, EMS care remains extremely uneven across the United States. Even when EMS is located within a publicly funded agency such as the fire service, it may receive a disproportionately small amount of fire service funding (including grants and line item disbursements), despite the fact that a large majority of calls to fire departments are medical in nature.

Fourth, EMS agencies face a number of personnel challenges. The training of EMTs and paramedics is uneven across the United States, and as a result, EMS professionals exhibit a wide range of skill levels. There are currently no national requirements for training, certification, or licensure, nor is there required national accreditation of schools that provide EMS training. In addition, recruitment and retention are significant challenges for EMS systems. The work of prehospital providers can be challenging and dangerous. EMS personnel face potential violence from patients; risks

due to bloodborne and airborne pathogens; and dangers from ambulance crashes, which increasingly result in provider fatalities (Franks et al., 2004). In addition, many EMS professionals are frustrated by low pay—the average salary for EMTs is about $18,000 and for paramedics is $34,000 (Brown et al., 2003)—and limited career growth opportunities, especially relative to firefighters and other public servants with whom they work side by side. Worse, they are often treated as second-class citizens by those same colleagues, by the systems in which they work, and by the state and federal institutions that fund and support the services they provide. As a result of these and other challenges, recently surveyed EMS agencies and administrators ranked recruitment and retention as the number one issue they face (EMS Insider, 2005).

Perhaps most disturbing is how little is known about what does and does not work in prehospital emergency care. There is little or no scientific evidence to support many widely employed EMS clinical procedures and system design features. The value and proper application of common clinical practices, such as rapid sequence intubation (Murray et al., 2000; Gausche et al., 2000; Davis et al., 2003; Wang et al., 2004) and cardiac resuscitation (Keim et al., 2004), remain unresolved. Field triage models that are widely considered to be out of date are still in use today. Evidence on the value of delivery models, such as tiered levels of response, intensity of on-line medical direction, type of EMS system (e.g., fire-based, volunteer), and deployment of paramedics, is either nonexistent or inconclusive.

The lack of available data on prehospital care not only discourages research on the effectiveness of prehospital interventions, but also hinders the development of process and outcome measures for evaluating the performance of the system. In fact, policy makers and the public have very little information on how well local EMS systems function and how care varies across jurisdictions.

Rural areas face a different set of problems, principally involving a scarcity of resources. EMS and trauma services are dispersed across wide distances, and recruitment and retention of EMTs and paramedics is a pervasive problem. In rural areas, volunteers make up the majority of the EMS workforce (National Registry of Emergency Medical Technicians, 2003). EMS is the only component of the U.S. medical system that has a significant volunteer component, but in many rural communities, younger residents are leaving as the remaining population becomes more elderly. As a result, the pool of potential volunteers is dwindling as their average age and the demands on their time increase. The closure or restructuring of many rural hospital facilities has further increased the demand on rural EMS agencies by creating an environment that requires long-distance, time-consuming, and high-risk interfacility transfers. The final section of this chapter provides a detailed discussion of rural EMS.

EMS is the first line of defense in responding to the medical needs of the public in the event of a disaster, yet EMS personnel are often the least prepared and most poorly equipped of all public safety personnel. According to New York University’s Center for Catastrophe Preparedness and Response, more than half of EMTs and paramedics have received less than 1 hour of training in dealing with biological and chemical agents and explosives since the September 11 terrorist attacks, and 20 percent have received no such training. Fewer than 33 percent of EMTs and paramedics have participated in a drill during the past year simulating a radiological, biological, or chemical attack. And in 25 states, half or fewer EMTs and paramedics have adequate personal protective equipment to respond to a biological or chemical attack (Center for Catastrophe Preparedness and Response NYU, 2005). These findings call into question the readiness of the current EMS system to deal with potential disasters.

FEDERAL OVERSIGHT AND FUNDING

The federal government is extremely fragmented in its approach to regulating EMS. A host of departments, divisions, and agencies at the federal level play a role in various aspects of EMS, but none is officially designated as the lead agency. With the passage of the Highway Safety Act in 1966, EMS found its unofficial home within NHTSA in DOT. At the time, a principal focus of the government’s effort in EMS was on reducing the number of deaths and disabilities caused by crashes on the nation’s motorways, so this placement within DOT seemed appropriate.

As described above, NHTSA’s Office of EMS has been able to provide significant leadership in the field over the past several decades. Indeed, since the early 1970s, NHTSA is the only federal agency that has consistently focused on improving the overall EMS system (AEMS, 2005a). However, NHTSA’s Office of EMS is a small program within a very large federal department that is devoted to transportation. Obscured as it often is within the vast federal bureaucracy, EMS is sometimes overlooked and at times virtually forgotten. This is evidenced by the fact that to date, EMS has received only a small percentage of homeland security funds allocated by the federal government. Although EMS providers represent a third of the nation’s first responders and have a key mission in treating the casualties of a terrorist strike, they received only 4 percent of the $3.38 billion allocated by the Department of Homeland Security for enhancing emergency preparedness in 2002 and 2003 (Center for Catastrophe Preparedness and Response NYU, 2005).

While NHTSA has served as the informal lead agency for EMS within the federal government, a number of other federal agencies also have a stake in EMS. DHHS houses several programs within HRSA, including

the EMS-C program and the Trauma and EMS Program (although both of these programs have been targeted for elimination in recent federal budgets). HRSA also administers the Office of Rural Health Policy. CMS is responsible for Medicare and Medicaid reimbursement for emergency services, which makes up a significant portion of EMS revenues. CDC’s NCIPC plays an important role in trauma and prevention research that is closely allied with emergency services. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) funds emergency- and trauma-related research. The Department of Homeland Security’s Preparedness Directorate supports emergency preparedness programs through the Chief Medical Officer, the U.S. Fire Administration, the Office of Grants and Training, and other agencies.

In an effort to coordinate the efforts of these various components of the federal bureaucracy, Congress established a Federal Interagency Committee on Emergency Medical Services (FICEMS) in 2005. This group was formed to ensure coordination among the federal agencies involved with state, local, or regional EMS and 9-1-1 systems and to identify ways of streamlining the process through which federal agencies provide support to these systems (see Chapter 3).

Federal Funding of EMS

Today, financial support for EMS is provided by the various departments and agencies that have jurisdiction over EMS. An array of federal grant programs provide limited amounts of funding to states, localities, and EMS providers (see Table 2-2 for examples). Typically, EMS receives a very small percentage of the funds devoted to larger programs.

Within DHHS, both HRSA and CDC fund EMS. HRSA operates a number of EMS-related programs, including trauma and EMS (funded at $3.5 million in fiscal year 2005), rural outreach grants ($39 million), hospital flex grants ($39 million), a poison control program ($23 million), and the EMS-C program ($23 million). As noted, however, recent budget proposals would eliminate several of these programs, including trauma and EMS, EMS-C, and the poison control program. By far the largest of the HRSA programs is the Hospital Bioterrorism Preparedness program ($495 million). This program aims to improve the capacity of hospitals, EDs, health centers, EMS systems, and poison control centers to respond to acts of terrorism and other public health emergencies. As detailed in Chapter 6, however, a very small percentage of these funds is directed to EMS.

CDC operates two large EMS-related programs. The Preventive Health and Health Services block grant ($131 million) provides states with resources to address priority health concerns in their communities. States are also charged with designing prevention and health promotion programs that address the national health objectives contained in Healthy People

TABLE 2-2 EMS-Related Fiscal Year 2005 Federal Funding

|

|

2005 Enacted Millions of Dollars |

|

Labor HHS & Education Bill |

|

|

Health and Human Services |

|

|

HRSA |

|

|

Rural EMS Training and Equipment |

0.5 |

|

Rural and Community Access to AEDs |

9 |

|

Hospital BT Preparedness |

495 |

|

Trauma/EMS |

3 |

|

EMS for Children |

20 |

|

Traumatic Brain Injury |

9 |

|

Rural Outreach Grants |

39 |

|

Rural Hospital Flex Grants |

39 |

|

Poison Control |

23 |

|

CDC |

|

|

Prevention Block Grant |

131 |

|

Injury Prevention (NCIPC) |

138 |

|

Transportation, Treasury Bill |

|

|

NHTSA |

|

|

EMS Division |

4 |

|

EMS State Grants |

0 |

|

Homeland Security Bill |

|

|

Office of Domestic Preparedness |

|

|

State and Local Programs: |

|

|

State Homeland Security Grant Program: |

1,100 |

|

Law enforcement terrorism prevention grants |

400 |

|

Urban Area Security Initiative: |

|

|

High-threat, high-density urban area |

885 |

|

Targeted infrastructure protection |

0 |

|

Buffer Zone Protection Program |

0 |

|

Port security grants |

150 |

|

Rail and transit security |

150 |

|

Trucking security grants |

5 |

|

Intercity bus security grants |

10 |

|

Commercial equipment direct assistance program |

50 |

|

National Programs: |

|

|

National domestic preparedness consortium |

135 |

|

National exercise program |

52 |

|

Technical assistance |

30 |

|

Metropolitan Medical Response System |

30 |

|

Demonstration training grants |

30 |

|

Continuing training grants |

25 |

|

Citizen Corps |

15 |

|

Evaluations and assessments |

14 |

|

Rural domestic preparedness consortium |

5 |

2010. These include increasing the proportion of adults who are aware of the early warning signs of a heart attack and the importance of accessing emergency care by calling 9-1-1 (GAO, 2001b). CDC also runs NCIPC, which works to reduce morbidity, disability, mortality, and costs associated with injuries (funded at $138 million in fiscal year 2005). Overall, however, a small percentage of the funds allotted to these CDC programs is devoted specifically to EMS.

The Department of Homeland Security’s Office of Domestic Preparedness awarded nearly $4 billion in federal funding in fiscal year 2005 under its first-responder grant programs—the Firefighter Assistance Grants program ($895 million) and the State and Local Programs fund ($3.1 billion). The latter included $885 million for high-threat, high-density urban areas; $150 million each for port security and rail and transit security; and $135 million for the national domestic preparedness consortium. As detailed in Chapter 6, however, non-EMS first responders were the primary recipients of these funds.

Federal Reimbursement for EMS Services

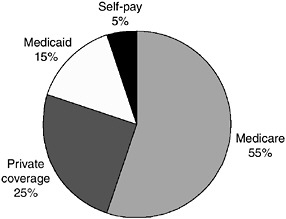

In addition to small portions of the federal funding detailed above, EMS systems across the country receive federal funds through reimbursements from the Medicare program. Because the elderly are heavy users of EMS, Medicare represents a very large percentage of billings and collections in a typical EMS agency. Those aged 65 and older are 4.4 times more likely to use EMS than younger individuals, and they represent a growing segment of the population. Since Medicare payments have traditionally been used to cross-subsidize Medicaid and uninsured EMS users, Medicare represents an even larger percentage of total patient revenues for EMS agencies (Overton,

2002). An example from the Richmond Ambulance Authority is shown in Figure 2-2. In that system, Medicare represents 40 percent of billings, but 55 percent of revenues.

The Medicare program recently completed a 5-year transition to a new fee schedule. Under the old reimbursement system, EMS agencies received two payments per transport. The primary payment was a cost-based, fee-for-service rate that reimbursed EMS for the service provided. The secondary payment was reimbursement for the number of miles the ambulance traveled. Under that system, ambulance services were concerned primarily with reporting their charges and mileage. The new system keeps the mileage reimbursement but abandons the cost-based payment and replaces it with a prospective payment system, similar to the system in place for outpatient health services (Overton, 2002). EMS was the last Medicare Part B provider to transition from a fee-for-service to a prospective payment system. Under the new system, ALS transports are reimbursed at a higher rate than basic life support (BLS) transports, and higher payments are provided for transport in rural areas to reflect the typically long travel times to and from hospitals (MedPAC, 2003).

Overall, the new fee schedule significantly reduces Medicare payments to EMS providers. Two years into the transition to the new system, data indicated that Medicare reimbursements were approximately 45 percent below the national cost average for transport, leading to a $600 million shortfall for services provided to Medicare beneficiaries. As a result, local EMS systems may now need greater subsidization from local governments or may be forced to reduce costs through personnel cuts, reductions in

FIGURE 2-2 EMS patient revenues, Richmond, Virginia.

SOURCE: Overton, 2002.

capital expenditures, or other means. These dynamics illustrate the tension among federal, state, and local governments regarding the locus of responsibility for funding EMS systems across the country.

Medicare payments have significantly shaped the provision of EMS nationwide, as evidenced in several areas, including the availability of responders, the therapeutic interventions provided, treat and release practices, and transport and transfer policies (NASEMSD, 2005). For example, EMS systems relying on Medicare and other third-party payers for significant revenue must generally provide patient transportation to be reimbursed for their services. While the primary determinants of EMS costs relate to maintaining readiness capacity, the primary determinant of payment for services is patient transport. Thus in an urban area that receives a large number of 9-1-1 calls, the cost of readiness is spread over a large number of users, keeping the cost per transport relatively low, whereas in rural areas, the lower volume of emergency calls in relation to the high overhead of maintaining a prepared staff results in very high costs per transport. Although many rural EMS squads rely on volunteers rather than paid EMS personnel to reduce these costs, doing so results in a less stable system.

Federal Regulation of EMS

The current organization and delivery of emergency and trauma care is shaped largely by federal and state legislation. The legal and regulatory framework provides many protections and benefits, but also presents obstacles to achieving efficient and high-quality care delivery.

Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act (EMTALA)

EMTALA represents one example of how the federal government’s fragmented regulatory structure has resulted in confusion for EMS providers and potential harm to emergency patients. This law, passed in 1986, requires hospitals that participate in the Medicare program to provide a medical screening exam and stabilize all patients that come to the hospital for care before they are discharged or transferred to another hospital. EMTALA was intended to protect access to emergency care by preventing private hospitals from turning away needy emergency patients who are uninsured or underinsured or precipitously transferring these patients to the closest public hospital, a practice known as “dumping” (GAO, 2001a).

Over time, the law has progressively expanded, and it now covers patients seen anywhere on hospital property, which includes ambulances owned and operated by the hospital (Wanerman, 2002; Elting and Toddy, 2003). As a result, hospitals may be required to provide medical screening exams to patients arriving in a hospital-owned ambulance even if the pa-

tient requires immediate care at a regional trauma center because the local hospital does not have the personnel or equipment required to respond effectively to the patient’s critical medical needs. This situation also arises in cases where a ground and an air ambulance are attempting to rendezvous at a hospital’s helipad so that the patient can be transported quickly to a trauma center. Providers in the field have experienced confusion as to whether a screening exam is mandated in this case.

The expansion of EMTALA to include transports by hospital-owned ambulances created a barrier to regional coordination. The goal of regional coordination is to ensure that patients receive the optimal care, and a key component of that task is ensuring that avoidable and costly delays are eliminated. However, EMTALA may require that patients receive initial care at a less-than-optimal facility, creating avoidable delays in the provision of needed care.

This problem is compounded by the fact that no one agency is responsible for making regulatory decisions regarding EMTALA, and as a consequence, federal rules on this issue are not clear. The Office of the Inspector General (OIG) has produced advisories on EMTALA, including a letter of opinion stating that ambulances may take patients directly to hospitals that are appropriate for the patient’s condition (including trauma centers) in cases where there are “regional protocols” in place (DHHS, 2003). However, the OIG is not a rule-making entity and is not responsible for enforcement. CMS’s enforcement of EMTALA has been shown to be highly variable among regions (GAO, 2001a). Consequently, providers across the country are uncertain as to whether EMTALA requires that a medical screening exam be conducted even when a patient requires immediate care at a trauma facility, and there is no simple or straightforward way to have this issue clarified. Various people involved in making the decision at the local level, including the hospital administrator, the hospital’s attorney, the state EMS office, and others, may all have a different point of view. As a result, providers are making decisions that may compromise care based on their own reading of this complex regulatory environment.

Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA)

The federal regulatory environment has also created confusion with HIPAA. Enacted to regulate the transmission of electronic health data among providers and payers and to protect the privacy of patient health information, HIPAA often presents challenges for providers seeking to share health information with other providers, potentially compromising both patient care and provider protections; it also creates difficulties for investigators seeking to obtain research data. There are exceptions to HIPAA that recognize the unique characteristics of emergency and trauma care, such

as the urgency of care and the potential inability of patients in distress to provide consent (Lewis et al., 2001); however, HIPAA continues to pose a number of impediments to EMS.

The regulatory environment at the federal level does not provide clear assurances regarding HIPAA rules for dispatch centers and radio communications, resulting in guesswork at the local level. EMS represents a small segment of the health care continuum and received little attention during the development of the HIPAA regulations, but the cost of HIPAA compliance for EMS providers is substantial.

Based on their interpretation of current federal rules and their fear of liability, some hospitals believe HIPAA excludes outside agencies from participating in multidisciplinary quality assurance projects. As a result, trauma morbidity and mortality conferences convened by hospitals may exclude EMS personnel. This happens despite the fact that EMS personnel are responsible for transporting patients to the hospital, often have salient information about events on the scene, and may benefit from learning what happened after patients reached the hospital.

HIPAA has created additional barriers to information sharing between hospitals and EMS agencies. For example, EMS agencies may want to assess patient outcomes following hospital transport; however, patient-specific outcome data often are not shared. EMS personnel may also seek to determine whether a particular patient transported to the hospital is suffering from an air- or bloodborne pathogen or some other malady that may compromise the safety of the transporting EMS personnel. But hospitals are often unwilling to share this information with EMS agencies for fear of violating HIPAA regulations, even in cases where such information sharing may be allowable.

For researchers investigating patient outcomes resulting from out-of-hospital interventions such as cardiac resuscitation, it is necessary to obtain outcome information from each of the facilities in which patients were treated. Out-of-hospital and ED records must be linked with hospital records, vital statistics, and coroner’s records when appropriate. The patient identifiers required to perform such linkages are subject to the confidentiality provisions of the HIPAA legislation, making gathering these data difficult in an environment where EMS-related research is already lacking.

EMS OVERSIGHT AT THE STATE LEVEL

In most states, state law governs the scope, authority, and operation of local EMS systems. Each state has a lead EMS agency that is typically a part of the state health department, but in some states may be part of the public safety department or an independent agency. The mission, funding, and size of EMS agencies vary considerably from state to state. For example,

a survey conducted by NASEMSO found that the number of full-time positions within state EMS agencies varied from a low of 4 to a high of 90. Most states have an EMS medical director, though many do not. Table 2-3 shows the range of functions that EMS agencies provide.

State EMS agencies regulate and oversee local and regional EMS systems and personnel. They typically license and certify EMS personnel and ambulance providers and establish testing and training requirements. Some may also be responsible for approving statewide EMS plans, allocating federal EMS resources, and monitoring performance (GAO, 2001b). States have begun to take a more proactive role in trauma planning, with 35 states having formal trauma systems. One key function of many EMS agencies is data collection. However, only about half of state EMS offices have the capabilities to provide information on how many EMS responses occur in their state (Mears, 2004).

In regulating local and regional EMS systems, many state EMS offices are placed in the difficult position of being both an advocate/technical advisor and a regulator. This dual role can create internal conflicts. For example, state EMS offices are often responsible for both ensuring an adequate supply of EMS personnel and regulating those personnel. If an EMS office seeks to increase the educational requirements for EMS personnel, it may also create the type of workforce shortage it is working to avoid. For this reason, other professions separate the regulatory and advocacy roles (Shimberg and Roederer, 1994; Schmitt and Shimberg, 1996).

TABLE 2-3 State EMS Agency Functions

|

Function |

States Performing (%) |

|

Complaint Investigation |

100 |

|

EMS Training Standards |

96 |

|

EMS System Planning |

94 |

|

Disciplinary Action of Personnel |

90 |

|

EMS Personnel Credentialing |

90 |

|

State EMS Data Collection |

88 |

|

Air Ambulance Credentialing |

84 |

|

Ambulance Inspections |

84 |

|

Ambulance Credentialing |

82 |

|

Disaster Planning |

78 |

|

Local EMS Technical Assistance |

74 |

|

Trauma System Management |

72 |

|

Local EMS Data Collection |

68 |

|

Medical Director Education |

62 |

|

Funding for Local EMS Operations |

34 |

|

Communications Operations |

18 |

|

SOURCE: Mears, 2004. |

|

Some states provide direct funding for EMS, which may be derived from vehicle or driver licensing fees, motor vehicle violations, or other taxes. However, EMS funding is subject to cutbacks in tight fiscal environments. Approximately 87 percent of funds for state EMS office budgets comes from in-state revenues. The remaining 13 percent that comes from the federal government includes grants from multiple agencies with diverse priorities. There is currently no single, comprehensive federal vision for the development of the EMS system nationwide. NASEMSO maintains that this situation may have contributed to the lack of sustained and meaningful development in many areas identified in Emergency Medcical Services Agenda for the Future (NASEMSD, 2005).

State Medicaid agencies are responsible for developing Medicaid reimbursement policies for EMS. It is estimated that for most EMS agencies, Medicaid patients represent 20–40 percent of all EMS patients. The proportion of users covered by Medicaid tends to be higher in rural areas. The way EMS services are reimbursed can vary greatly from state to state; however, Medicaid reimbursement rates are almost universally low. As noted earlier, the majority of states use a fee-for-service payment system and a mileage rate for Medicaid reimbursement; five states pay EMS a “reasonable charge,” an amount that the state has decided is reasonable for the public to pay (Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, 2003). Medicaid reimbursement is typically based on transportation rather than service provided. Thus, for example, EMS agencies in Virginia receive $75 for transporting a patient 0–5 miles to a hospital, regardless of whether the patient was transported by BLS or ALS providers and regardless of the severity of the patient’s condition or the services rendered. In most states, payment is not provided unless the EMS agency actually transports the patient.

NHTSA provides some technical assistance to state EMS agencies through statewide assessments. For the assessments and reassessments, NHTSA serves as a facilitator by assembling a team of experts in EMS development and implementation to work with and advise the state. The state EMS office provides NHTSA and the assessment team with background information on the EMS system, and the technical assistance team develops a findings report. A mid-1990s review of EMS assessments revealed “widespread fundamental problems in most areas,” but the lack of quality management programs was a common theme across systems. The review found that the majority of states did not have quality improvement programs for evaluating patient care, methods for assessing current levels of system resources, or mechanisms for identifying necessary system improvements (NHTSA Technical Assistance Program, 2000). The technical assistance provided to state EMS agencies is critical. All of these agencies face complex structural and operational issues that include system design, reimbursement strategies, quality management, performance improvement, and business

remodeling. EMS administrators are typically career EMS personnel; many have little formal training in organizational management, and there are no standardized courses for providing them with this training (Mears, 2004).

MODELS OF ORGANIZATION AND SERVICE DELIVERY AT THE LOCAL LEVEL

Across the United States today, EMS systems are fundamentally local in nature (GAO, 2001b). Counties and municipalities play central roles in deciding how their systems will be structured and how they will adapt to changes in the environment (e.g., changes in Medicare payment rates or added liability concerns). They determine the organization of the delivery system, the structure of EMS response times, the development of finance mechanisms, and the management of other system components. As a result of this local control, EMS systems across the country are extremely variable and fragmented. This diversity of systems can be viewed as a strength in that it promotes local self-determination and tailors systems to the needs and expectations of local residents. However, it is also a profound weakness, especially in cases where local standards of care fall below generally accepted standards and patients suffer as a result. Across cities, for example, the percentage of people suffering ventricular fibrillation who survive and are later discharged from the hospital with good brain function ranges from 3 to 45 percent (Davis, 2003a). EMS response times overall vary substantially, and many cities do not collect the data necessary to track their performance.

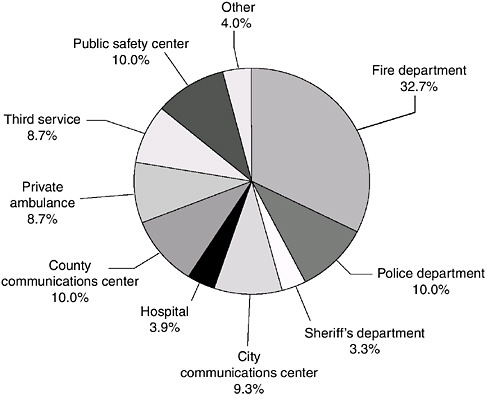

Emergency Dispatch Centers

Today, virtually all Americans (99 percent) have access to 9-1-1 service (National Emergency Number Association, 2004). However, the apparent uniformity of the 9-1-1 system is misleading: the system is actually locally based and operated, and its structure varies widely across the country. There currently exist more than 6,000 public safety answering points (PSAPs), or 9-1-1 call centers, nationwide. These include both primary PSAPs, which field all types of 9-1-1 calls (police, fire, and EMS), and secondary PSAPs, which handle service-specific calls, such as medical emergencies. These emergency call centers are operated primarily by public safety agencies, as well as city and county communications centers, hospitals, and others (see Figure 2-3). Over time, it may become necessary to reduce the large number of call centers, especially in the context of disaster preparedness efforts, which dictate a more streamlined emergency call structure in response to catastrophic events.

In 2004, 9-1-1 call centers fielded approximately 200 million emergency calls, including medical, police, fire, and other calls. In some cases, medical

FIGURE 2-3 Agency responsible for dispatch in the 200 most populous cities.

SOURCE: Monosky, 2004.

calls are received by primary call centers and then routed to secondary calls centers with dedicated medical dispatch. In other cases, all calls are handled at the primary call center. When different types of calls are handled by different call centers, the potential for “call switching” and miscommunication is dramatically increased.

Not only do 9-1-1 dispatchers determine the appropriate level of response, but they also often provide prearrival instructions to the caller. The prototype for this process was dispatcher-assisted CPR, pioneered by Eisenberg and colleagues in King County, Washington, and subsequently validated by an independent research team in Memphis. The list of conditions amenable to prearrival instructions was quickly expanded to include, for example, childbirth, seizures, and trauma/bleeding.

Prearrival instructions are designed to enable the caller to provide assistance when certain emergency conditions are present, to protect the

patient and caller from potential hazards, and to protect the patient from well-meaning bystanders who could provide assistance that might do more harm than good (Hauert, 1990). The level of prearrival assistance from the dispatcher can vary from simple advice, such as “call a doctor,” to instructions for performing CPR. Instructions are typically available to the dispatcher on flip cards.

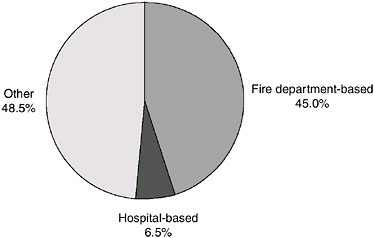

EMS Systems

A survey of EMS systems conducted in 2003 by NASEMSD and HRSA’s Office of Rural Health Policy indicated that there were 15,691 credentialed EMS systems in the United States (Mears, 2004). However, the survey also indicated that the definition of an EMS system varies from state to state, making accurate tabulations nearly impossible. Among the systems identified by the survey, 45 percent were fire department–based, 6.5 percent were hospital-based, and 48.5 percent were labeled as neither (see Figure 2-4). The total number of ALS and BLS transport vehicles reported was 24,570. More recent data from the American Ambulance Association (AAA) indicate that there are 12,254 ambulance services operating in the United States (a figure that includes private for-profit and not-for-profit, hospital-based, volunteer, and fire department–based services), and a total of 23,575 ground ambulance vehicles (AAA, 2006).

While no statistics are available to provide greater detail about EMS system types nationwide, the Journal of Emergency Medical Services conducts an annual survey of the 200 largest metropolitan areas in the United

FIGURE 2-4 Types of EMS systems.

SOURCE: Mears, 2004.

TABLE 2-4 Reported Provider Types

|

Provider Type |

Percentage (Number) |

|

|

First Responders (n = 163) |

|

|

|

Fire Department |

89.0 |

(145) |

|

Other |

7.4 |

(12) |

|

None |

3.7 |

(6) |

|

Transport Providers (n =163) |

|

|

|

Private Organization |

36.2 |

(59) |

|

For-Profit |

31.3 |

(51) |

|

Not-for-Profit |

4.9 |

(8) |

|

Fire Department |

31.9 |

(52) |

|

Single-Role |

4.9 |

(8) |

|

Dual-Role |

27.0 |

(44) |

|

Third Service |

8.6 |

(14) |

|

Hospital |

7.4 |

(12) |

|

Other |

4.9 |

(8) |

|

Public–Private Partnership |

4.3 |

(7) |

|

Public Utility Model |

3.7 |

(6) |

|

Public Safety |

1.2 |

(2) |

|

Volunteer |

1.2 |

(2) |

|

SOURCE: Williams, 2005. |

||

States and is able to provide statistics for these areas (Williams, 2005) (see Table 2-4). The figures shown do not reflect smaller cities or rural areas. Results of the 2006 survey indicate that 36 percent of ambulance systems in these large metropolitan areas are private (either for-profit or not-for-profit), 32 percent are fire department–based, and just under 10 percent are third-service and hospital-based. However, an overwhelming number of first responders are fire department–based (89 percent).

Fire Department–Based EMS Systems

As is evident from the Mears (2004) survey, a strong plurality of EMS systems nationwide is fire department–based. The number of services has steadily increased over the past several decades as fire chiefs have recognized the central role of EMS in firefighting operations. EMS is an element of the response and service delivery of approximately 80 percent of fire departments in America (U.S. Fire Administration, 2005).

At an operational level, a fire department–based EMS system is one in which EMS is part of the fire department and ambulances are housed in or operate out of fire stations, with integrated dispatch. The integration of fire and EMS varies with each department. Some departments utilize person-

nel whose sole function is to provide EMS, while others utilize dual-role personnel who function as both firefighters and EMS providers. Some fire departments offer a full range of EMS, including BLS and ALS response and transport, while others limit their role to providing first-responder BLS or ALS care without transport.

Fire departments have chief officers who oversee operations and provide leadership at multiple levels. The chief of the department is usually a firefighter and, increasingly, may also have an EMS background, although frequently this is not the case. The organization and leadership of EMS within fire departments vary considerably. Some departments divide EMS and firefighting into separate divisions, while others integrate the two services under general operations. All fire departments that provide ALS must have a physician medical director, whether paid or volunteer; those that provide only BLS services may not.

Fire departments are financed primarily through public funds. Some departments bill for EMS, but collection rates vary. Collections are especially low in urban areas. Many small-town and rural fire departments in the United States, especially the latter, are volunteer, but the number of volunteer firefighters appears to be declining (see the discussion in Chapter 4).

In most jurisdictions, EMS calls now exceed fire-related calls by a wide margin. According to the National Fire Protection Association (2005), 80 percent of national fire service calls are EMS-related. This trend is likely to persist as fire prevention techniques continue to improve and as the aging of the U.S. population adds to the projected number of EMS calls.

One advantage of having an integrated fire and EMS system is structural efficiency. Firehouses are traditionally well positioned to serve the local population in most areas of the country. These physical structures can provide a strategic location for the EMS units they house, as well as a place for EMS personnel to rest between calls. Fire departments also provide the administrative infrastructure necessary to manage personnel, provide training, and purchase and maintain equipment and supplies.

But there are also disadvantages to fire-based EMS systems. A series of articles in USA Today documented the cultural divide, discussed earlier, that can exist between EMS and fire personnel (Davis, 2003b). Generally, the orientation of EMS personnel centers on providing medical care, whereas that of firefighters centers on conducting rescue operations and battling fires. As a result, there is some difference between the types of individual who become EMTs and firefighters (Davis, 2003a). These personnel often do not work together in a coordinated fashion.

In many cities, such as Washington, D.C., and Los Angeles, EMS is under the leadership of the fire department, which tends to consider fire suppression its principal mission, with medical services assuming a secondary role (Davis, 2003a). As a result, priority is given to fire suppression when

it comes to training and budget allocations. In many cases, firefighters are paid more than EMS personnel and have separate unions and command structures, even when based within the same fire department. Medical directors who are hired to supervise fire department–based emergency medical response may be viewed as outsiders, and may defer to the fire chiefs on the way resources should be deployed. Over the past decade, many EMS systems have become integrated with the fire service, although there is significant variation with respect to the level of integration.

Hospital-Based EMS Systems

Hospital-based EMS systems may provide stand-alone EMS coverage to a community or may operate in conjunction with a fire department. Typically, a hospital-based service is located at a community hospital and dispatched through a public safety communications system (9-1-1) or routed through a secondary call center that receives dispatches from a 9-1-1 center. Hospital-based systems function as private entities and typically bill for their services.

An advantage of a hospital-based system is that EMS personnel may benefit from the closer relationship between the ED and the hospital and may be better able to maintain professional skills through greater opportunities to observe ED procedures. Hospital-based systems also benefit from the reputation of the hospital with which they are affiliated and may be recognized by members of the community.

A challenge for hospital-based systems is potential competition among services and the need for better coordination of system resources. Since hospital-based ambulances bill for services and provide transport to their base hospital, there is an inherent competition for patients. For example, ambulance companies may seek to advertise their services, providing their own phone number and encouraging people to call them instead of 9-1-1. This may also occur with private ambulance services.

Another challenge in larger communities that use a number of hospital-based systems is optimizing system resources. Hospitals are not always located proportionally to populations or areas of greatest need. Further, depending on state regulations, hospitals may not be required to increase the number of available ambulances if EMS call volumes increase.

Private Systems

In some areas, local governments run their ambulance service by contracting with a private entity—either a local EMS operation or a national company. In these instances, private ambulance companies contract their services to local governments to provide 9-1-1 transports, including person-

nel, equipment, and vehicles. The contracts may or may not require medical oversight. The private firms compete for contracts, typically every several years. Some of these private firms are publicly owned stock-issuing corporations. For-profit providers now operate throughout most of the country.

Private EMS systems face some of the same challenges as fire department–based EMS systems. Some cities have found them to be a more economical alternative than expanding fire departments to provide EMS. However, their profit orientation also makes it more likely that EMS will suffer when contract disputes occur with the municipal agency.

There are several different models for private systems. First, under a level-of-effort model, a local government develops a contract with a private firm for a certain number of ambulances and other resources. The contractor is not held to specific performance standards, but must simply provide the contracted services. Under a performance-based model, the contractor is expected to meet specific performance standards to fulfill the contract. Finally, under a high-performance model, the contract creates a business relationship that tightly aligns the interests of the contractor with public needs. The contractor may be responsible for patient billing and may own some long-term infrastructure items, such as ambulances and medical communications systems. Additionally, an independent body is responsible for performance, medical oversight, and financial oversight; rate regulation; licensing; and market allocation (AAA, 2004).

One difficulty in evaluating the pros and cons of any service model (whether locally or nationally) is the dearth of objective process and outcome data for comparing one model of service delivery or even one ambulance company with another. As a result, local governments frequently rely on crude measures, such as numbers of personnel, numbers of ambulances operating per unit of time, EMS fractile response times by urgency of call, and patient complaints. These are poor proxies for quality of care and outcome-based measures of system performance.

Municipal Services

At the local level, municipal and county governments often deliberate between contracting out to a private EMS company and developing and operating an EMS unit themselves. In many cases, the locality chooses the latter option. This involves purchasing or leasing ambulance units, hiring EMS personnel to provide direct services and administrative personnel to run the program, and stocking ambulances with necessary medical and communications equipment. Some of these operations bill private insurers for services, while others rely solely on direct funding from the city or county.

In Kansas City, Missouri, fire department personnel serve as first responders, but transport is handled through a public utility model. This

model entails a quasigovernmental authority with overall responsibility for EMS transport that owns all the equipment, including ambulances, and carries out billing and other logistical functions, but contracts with a private company for human resources. Kansas City was one of the first major cities to offer EMS transport using this model.

EMS System Staffing: Career- and Volunteer-Based

In career-based EMS systems, providers are paid to staff the ambulance units and have preassigned shifts. Benefits of such a system are thought to include greater standardization in the quality of patient care through employer oversight, mandated training, and quality assurance and improvement. Many states and communities, however, still rely heavily on volunteers to provide ambulance coverage; in particular, volunteer personnel have traditionally been the lifeblood of rural EMS agencies. Volunteers may also have preassigned shifts but generally are not paid for their time, although recent research suggests that a fairly large percentage of volunteers receive financial compensation for their EMS activity (Margolis and Studnek, 2006). Equipment and vehicles are frequently maintained using donations or public funds. Oversight of volunteer systems is sometimes provided by the municipal or county agency responsible for EMS, if one exists. The benefits of a volunteer system include the significant cost savings from not having to pay personnel. However, the challenge is maintaining a response system that consistently meets the public demand for quality services.

Most experts agree that there appears to be a national trend toward decreasing volunteerism and an increase in EMS personnel seeking paid careers. During the early stages of EMS, it was not uncommon for volunteers to be on call nearly 24 hours a day. Today, however, increased time demands, the rise in families’ needs for dual incomes, and vying interests create an environment in which volunteers may donate one specific weeknight or a few hours on a weekend. As a result, rural EMS agencies in particular are currently faced with volunteer staffing shortages, particularly during weekday work hours.

Many systems are a combination of volunteer- and career-based because of the challenges of maintaining an entirely volunteer system. Such combined systems represent an attempt to achieve cost savings while ensuring adequate services to the public. However, the sustainability of each type of system—career, volunteer, and combination—is unclear as a result of the resource demands on career systems and the lack of personnel for volunteer systems.

Air Ambulance Systems

Air medical operations have grown substantially since their inception in the 1970s. Today there are an estimated 650–700 medical helicopters operating in the United States (Gearhart et al., 1997; Helicopter Association International, 2005; Meier, 2005; Baker et al., 2006), up from approximately 230 in 1990 (Blumen and UCAN Safety Committee, 2002; Helicopter Association International, 2005). These helicopter operations are owned and managed by a variety of entities, including for-profit providers, nonprofit organizations such as local hospitals, government agencies such as the state police, and military air medical service providers. Many air medical providers were originally employed as hospital contractors but now work on an independent basis. Typically, the base helipads for these providers are located in airports, independent hangars and helipads, and designated areas of a hospital (Branas et al., 2005).

Air ambulance operations have served thousands of critically ill or injured persons over the past several decades (Blumen and UCAN Safety Committee, 2002). However, there has been growing concern about the safety of these operations. Approximately 200 people have lost their lives as a result of air medical crashes since 1972, and these deaths have been increasing as the industry continues to expand (Blumen and UCAN Safety Committee, 2002; Bledsoe, 2003; Baker et al., 2006). Crashes are often attributable to pilots flying in poor weather or at night. Li and colleagues (2001) found a four-fold risk of a fatal crash in flights that encountered reduced visibility. Baker and colleagues (2006) found that crashes in darkness represented 48 percent of all crashes and 68 percent of all fatal crashes. In addition, some companies are flying older, single-engine helicopters that lack the instruments needed to help pilots navigate safely (Meier, 2005). In 2004 and 2005 a total of 12 fatal air ambulance crashes occurred—the highest number of fatal crashes in two consecutive years experienced in the industry’s history (Isakov, 2006). Recent increases in Medicare payments have led to greater competition in the industry, which has added to concerns regarding safety (Meier, 2005).

Air medical services are believed to improve patient outcomes because of two primary factors: reduced transport time to definitive care and a higher skill mix applied during transport. However, presumed gains in transport time do not necessarily occur, given the time it takes the helicopter crew to launch, find a suitable landing position, and provide care at the scene. This is especially true when the distance to the scene is short. Questions have also been raised regarding the appropriateness of air ambulance deployments in specific patient care situations (Schiller et al., 1988; Moront et al., 1996; Cunningham et al., 1997; Arfken et al., 1998; Dula et al., 2000). A 2002 study found that helicopters were used excessively for patients who were not

severely injured and that they often did not deliver patients to the hospital more rapidly than ground ambulances (Levin and Davis, 2005).