4

The Value of Technological Innovation in Home Construction and the Role of Government/Industry Partnerships in Promoting Innovation

Sarah Slaughter

MOCA Systems

I have spent considerable time looking at innovations and their diffusion and commercialization. Not only did I study innovation for many years, but also I have been living the process for the last ten years. Ten years ago I headed a team at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) Civil and Environmental Engineering Department that started developing a construction simulation system through research sponsored by the National Science Foundation. After about five years, many of the industry participants in that research started asking us if they could start using the simulation technology. In response, I started a company called MOCA Systems and I left MIT in 2000 to further develop and commercialize the simulation system. We have been working on the whole process of commercialization and diffusion. At this point, I am a recovering academic and truly believe in the importance of the PATH mission to advance technology.

Looking at the challenges that are specific to the housing industry, it is important to consider innovation from the owner or occupant’s point of view. Consumer objectives for housing improvement include:

-

More healthful;

-

Safer (in natural disasters);

-

More sustainable;

-

Affordable to buy;

-

Affordable to run;

-

Available more quickly; and

-

Easier to maintain, repair, and upgrade.

We hear a lot of stories about mold, not only from post-Hurricane Katrina flooding, but also in the living environments of people in different parts of the United States. In some climatic areas, the issue of a healthful home is critical.

A second aspect that cannot be ignored, especially after a year of several natural disasters, is the ability of houses to withstand these extreme conditions. A home should be a safe haven in the case of a natural disaster—whether it is a blizzard, a flood, a hurricane, or an earthquake. For example, a group of students have designed a new type of home that can withstand the forces found in a tsunami for areas in the South Pacific.

Consumers are also concerned about the materials used in home construction and how they can be made more sustainable and make the most efficient use of environmental resources. This includes energy efficiency, as well as the use of construction materials.

Affordability is an important issue. Many young people today cannot afford to live anywhere near a major city. Some of them are commuting two hours into a city because they cannot find affordable housing closer to their workplace. This makes a huge impact on economic development in our country.

Homes also need to be affordable to operate. Anyone who has looked at the cost of heating his or

her house is concerned about increasing energy efficiency. Consumers are also concerned about the cost of maintenance activities that are required to keep a house in good condition and to keep the value of their primary asset.

The amount of time required to build a house is also a concern. For all of the people who are in the Gulf Coast area, the speed at which new houses are going to be delivered is absolutely critical. Once built, houses may exist for several hundred years. In Boston, there are houses that have been around since the 1600s. We need to recognize that houses need to be durable and also be able to accommodate changes over time.

The original PATH goals were to:

-

Reduce cost by 20 percent,

-

Reduce environmental impact by 50 percent,

-

Reduce maintenance costs by 50 percent,

-

Improve occupant safety by 10 percent, and

-

Improve worker safety by 20 percent.

The NRC assessment determined that these goals were inappropriate for PATH. They may be inappropriate for PATH, but these types of goals are consistently used to manage companies. However, in construction we always say they are not possible. We can do it in construction if we really focus on how they can be accomplished most effectively. It is not impossible, since many innovative techniques, materials, processes, and equipment are available to achieve these goals if they can be applied effectively.

For an entrepreneur, there are really only two ways to succeed. One is to respond to an existing demand—provide a faster computer or a better soap. The second is to create demand. Responding to demand and creating demand are very different strategies and they have different measurements in terms of their effectiveness, time periods, risks, and distributions of benefits.

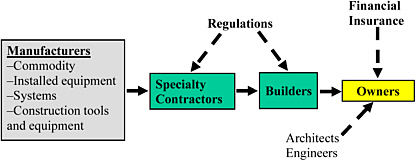

In residential construction, the primary drivers of demand for innovation are the builders, which include the general contractors and the specialty contractors, and the owners or consumers of the homes (Table 4.1). In residential construction, as opposed to commercial construction, there is an enormous variety of owners, from the individual who owns one or two houses, to an organization, like the Air Force, that owns thousands of homes.

Owners are responsible for financing the house and for funding long-term operations and maintenance. This becomes an important leverage point in the construction industry. Builders, both the general contractors as well as the specialty contractors, influence innovation because they are responsible for buying materials, installing equipment and specialty systems, and using construction tools and equipment.

The manufacturers influence both the general and specialty contractors. Also, there is the influence of the architects and engineers. When we think about the design of a building—the specific layout and the specification of the systems and materials that are installed, the architects and engineers can be a key leverage point for bringing in new technologies. They tend to seek new information and to use their resources to identify the technologies that are available, assess their impacts, and use this information in different environments.

The differences in innovation in residential construction compared to commercial construction are in part due to a less direct involvement of architects and engineers for specific buildings. Architects that work with large residential builders do not have the same influence on the selection of material and systems as they do in commercial construction. For commercial construction, there is a direct contract between the owner and the architect/engineer (A/E) and the A/E is responsible for identifying the critical needs and translating them into innovative designs and specifications. In residential construction there is much less involvement of the A/Es. Consequently, A/Es do not provide a strong a conduit for the identification and use of innovations in residential construction.

In commercial construction there is often a direct relationship between the builders and the material producers and suppliers. In residential construction, because there are many more and smaller

builders, the distribution channel acts as a filter, or in some ways as a barrier to communications between the manufacturers and the buyers of the products. The filtering of communications in the distribution channel influences the diffusion of innovations in the residential construction industry.

Commercial projects, by their nature, use a larger volume of materials than do residential projects. This impacts the strategies for the manufacturers and how they focus their resources to bring out new technologies and reach the critical mass for sustainable diffusion in the industry, which often entails focusing on commercial markets rather than residential applications.

The large builders in residential construction can be an incredible leverage point. There is often a direct connection between the choices offered to the owner and the builders’ preferences for equipment, processes, and materials. In residential construction the builder says, “This is what we build, would you like to buy it?” In commercial construction, the owner says, “This is what I want, who is going to build it for me?”

For residential construction, there are three major sources of innovations: manufacturers, builders, and owners. The types of innovations that manufacturers, builders, and owners come up with are very different and the benefits that they are looking for are also very different. The diffusion of innovations is driven by the balance between the relative benefits and the costs, and the distribution of the costs, risks, and benefits.

There is often a focus, particularly in the construction industry, on manufacturers as a key source of innovation. Manufacturers are looking for commercialized products, often innovations that can be imbedded in a physical object or system. The reason that they are coming out with these new products is that they expect higher margins, an expanded market share, or a new market share.

TABLE 4.1 Sources of Innovation

|

Source |

Type of Innovation |

Benefits |

|

Manufacturers |

Commercialized Products |

Higher Margin Expanded Market Share New Market |

|

Builders, including specialty contractors |

Process Construction Integration Prototype Products |

Higher Margin Faster Better Reputation |

|

Owners |

Prototype Process Prototype Product |

New Function Better Performance Lower O&M More Attractive |

There are builders, both general contractors and specialty contractors, who innovate all the time. If you have ever gone to one of the watering holes where the builders hang out after work, you would hear that they are constantly talking about the problems they ran into that day, and what they did to solve them. There is a constant identification of problems and the solutions to those problems because they have to keep the construction going. They can’t stop to call up the engineer or the manufacturer, and then wait weeks for an answer.

Builders come up with two types of innovations: process and product innovations. Process innovations offer the potential for the builders to become more efficient, more productive and effectively use resources to achieve a higher profit margin. Builders are also motivated to adopt innovations that increase the speed of construction, because if they are on a project too long, fewer houses are going to be

built and sold.

The other type of innovation is the use of new and better products. Builders are concerned about their reputations and the reputations of the products (i.e., homes) that they produce. The selection of a homebuilder is often based on a reference from the last home buyer. Builders are constantly innovating by integrating components produced by a myriad of manufacturers. They have to solve the problem of how the elements are going to work together. Builders often come up with prototype innovations for products. They will say, “I need a tool or a component that does this” and develop it.

Interestingly, owners will also innovate by solving specific problems. They are generally not going to obtain the benefits from improving the construction process. What they want is a house that has a new functionality, for example, the newest telecommunications, and they often innovate in how to add this functionality without ruining the house.

Then there are aspects of better performance. Anyone who is paying higher fuel bills this winter is going to start looking at how to improve the energy efficiency of their house. They may be putting plastic over the windows or doing a lot of other things to improve performance. The homeowner may also be looking for lower maintenance costs. If New England winters are tough on wood siding, owners want alternative materials that provide better performance and at the same time maintain or improve a home’s comfort and aesthetic appeal. The types of innovations developed by homeowners are prototypes because they are not going to obtain the benefits from using that innovation over time. Rather, they are looking to solve their current need.

There are two drivers of the diffusion of innovations: creating demand (also called technology push) and responding to demand (also called demand pull).

In the early days of personal digital assistants (PDAs), nobody really knew that they needed one. Now everybody has them. I have one built into my phone. In the case of PDAs, the demand was created. It was technology push. The risk for an innovator is that they may not be able to reach the critical mass of demand to achieve full diffusion.

In residential construction, the fragmentation of the market makes it difficult to reach that critical mass of buyers. The early adopters are difficult to find and communicate with. Manufacturers of new products may go to every homebuilding show and still only meet a small fraction of the potential market in any one geographical area. The fragmentation of the residential construction industry makes a technology push approach very difficult.

Because every single house is different, risk is also an issue. Given technologies A, B, and C and adding D as the innovation, but switching A to put in F, could lead to everything falling apart. A classic case is the delamination of fire retardant plywood. It was approved, it performed well under certain conditions, but when it was used in a new condition, there were massive failures that put homebuilders at incredible risk. When applying technology push, there is a need to identify the risks associated with innovations, particularly when there is a constantly changing set of complementary technologies that are all being incorporated into buildings.

The identification of benefits and who captures the benefits can be a risk for the technology source. For example, if there is a great innovation, but the only people who can obtain that innovation are large-scale builders, then the manufacturer needs to prove to the large-scale builders that they will benefit from that innovation. That then leads to the central aspect of technology diffusion—dissemination of information.

The type of information required for housing differs so significantly throughout the United States—from Alaska to Hawaii, from Florida to Maine—that when a technology source is trying to create demand, it may face significant issues in deciding what information is going to be applicable to each user. The user may be either the builder or the homeowner. The diversity of environmental requirements, preferred design styles, and the application of technologies differ, and so does the information needed to create demand.

There is also the information about the application of new technologies. There is an incredibly diverse work force associated with homebuilding. Even within a single trade there are different training programs. How much and what kind of information does the manufacturer need to provide—in what

format, in what language, how much of it is text and how much of it is pictures? The answer to these questions becomes critical to the success of a new technology.

The final issue regarding information is keeping the fragmented, diverse, and constantly changing set of users of the innovations up to date with information about the long-term impacts and particularly issues regarding the integration of technologies. When using technology push, there needs to be a continuing relationship between the early adopters, the mid-adopters, and the late adopters to maintain the diffusion momentum of that innovation.

There are interesting exceptions to the impact of these market risks for technology push in residential construction. Two of them are non-profits and the federal government. In these sectors, organizations can effectively develop technologies that are needed, as well as develop the demand because they are not affected by market risk in the same way as a private company.

For the government, the expenditure of public funds for anything that is connected with a public good can be easily justifiable. Improvement of worker safety and improvement of energy efficiency are examples. During the fuel crisis in the 1970s, there was a big push to develop technologies that responded to the increasing fuel prices; this had an enormous impact on the housing industry.

Universities can be an incredible source of information for technology push in developing basic theories and approaches and translating them into physical forms and processes by developing prototypes. However, there are risks when the government and universities are the sources of technology push. There can be a gap between the development of applied technology and the commercialization of that technology because of organizational mandates.

MOCA’s experience in creating a commercialized software system from the results of research undertaken at the MIT is a perfect example. It took a lot of effort to commercialize that technology. The gap between the development of applied technology and creation of a commercialized product is where there is huge risk. The question is, Who bears that risk and under what conditions?

PATH can effectively respond to the requirements associated with technology push in several ways. One is to facilitate demand development. There are a number of specific areas in which that can be fairly easy to accomplish. In some cases, there may be existing relevant demand, but the demand may not have been identified so that someone can respond by developing an innovation. Another is to publicize the benefits and the relative risks in a way that helps adopters make decisions based on the distribution of the costs and benefits. Potential adopters will adopt a new technology when the benefits are greater than the risks. Interestingly, regulations can also drive demand. Requirements for energy efficiency have led to improved construction and more efficient appliances. Regulations have also driven demand for innovation in the auto industry.

In residential construction, both the financial and insurance sectors have contributed to creating demand for innovation. An insurance company can lower premiums for the use of technologies that make a house safer and more resistant to natural hazards. Other organizations, like utilities, create demand by offering rewards to people who reduce the consumption of energy in their houses.

Reducing risks can also increase demand. There are a number of different ways in which the federal government and other organizations can reduce the risk of adopting innovations. One of them is to develop capacity. By increasing capacity, the heterogeneity in user population is decreased. For example, a consistent training program for residential electricians reduces risk by increasing homogeneity of information and facilitating its flow. There are also ways to look at distribution channels to determine how products and services are being delivered to the different user groups. For example, Internet search engines that can help buyers to find what they are looking for can create an incredible shift that allows the direct acquisition of materials, systems, components, and equipment and the relationships between buyers and suppliers.

Production equipment can also influence the development and diffusion of technologies. For example, Air Products, Inc., developed a coating system for low emissivity (low-E) windows. They wanted to sell specialty gases that were used to apply this coating. At first, none of the window manufacturers wanted to use the technology because it required new production equipment. So Air Products developed the production equipment and leased it to the window manufacturers on a long-term

basis in order to overcome that particular obstacle. Low-E windows now have a 95 to 99 percent market share. It took two and a half years to achieve that kind of market penetration. This is an example of looking at elements in the production chain to determine what is needed to use diffuse innovation.

Tests and standards are a way of decreasing the risk inherent in the diffusion of innovations. The rate of diffusion is increased when information is immediately available and people in different parts of the country know what works well for their specific conditions and how a product has performed with other systems.

Pulling together potential buyers and potential commercializing entities to bid on the rights to commercialize innovations can stimulate pre-commercialization efforts, but requires full disclosure of what it will take to transform applied research into a commercial product.

When using demand pull to diffuse innovation, the first step is to identify what is actually going on and problems that people are running into. When starting the work that eventually became MOCA, I worked with builders to determine what problems they were encountering. I stayed on the construction sites, watched what they were doing, watched what the problems were, and talked to the builders about the problems they were encountering. In this way, I learned about the specific systems and processes. Identify the problems provided an opportunity to present solutions.

There is demand for innovation from both builders and consumers. Consumers have incentives to look at long-term performance, and builders do not win bids when their projects don’t work well for consumers. When the needs of both builders and consumers are aligned, the strength of that demand increases.

Within the consumers’ critical requirements are aspects of short-term versus long-term performance, as well as accommodation for change. Frank Lloyd Wright came up with a beautiful Usonian house that was made from cast-in-place concrete. It had many wonderful attributes, but it was not flexible in accommodating changes over time, and most people like to add on to and change their house. The Levittown house is an example of built-in flexibility. When first built, they were all the same. Now they are all different. The fact that they were working off the same basic structure often cannot be seen. Being able to accommodate change over time can be important.

PATH can facilitate direct contact between the sources of demand and innovation. Often an organization has an innovation but doesn’t know how to get to the people who would be able to use it. There are issues that are associated with applicability, relevance, and the distribution of benefits and costs. Creating showcase environments can work for these situations. There can also be special convocations of producers and users within certain geographic areas or market segments, allowing a direct connection between the sources of the innovation and the users of the innovation.

In commercial construction, a new product, system, process, or equipment may be slightly wrong when first introduced. Maybe the flange is in the wrong place, or maybe it is just too large in one dimension. If the manufacturers do not have direct connections with the users, they do not know why the product is not selling. If there is direct connection between the sources of the innovation and the users of the innovation, there can be renewal, revision, modification, and improvement of those innovations to meet user requirements.

The distribution of information can also be modified. Ten years ago, architects, engineers, and builders all had volumes of the Sweets Catalogues on their shelves. When they needed information about possible products to solve a problem, they would pull out the book and look through it. Now, Sweets Catalogues are online, and there are also alternatives, such as using an Internet search engine. However, this can be a problem, because the quality of the information is not known. There has been an incredible increase in the availability of information without a system to evaluate the quality of the information from so many different sources. In construction, the distribution channels for information are changing, but there is also an increased risk from those different sources.

Manufacturers of equipment and other high-tech companies constantly talk to their users. They know the users have been modifying their product. For example, in a medical laboratory, any given piece of testing equipment will probably be modified within a year. It either needs to be connected up with something that was never anticipated, or the users have discovered how to make it work more efficiently.

A lot of manufacturers visit their lead users—the ones who are most likely to come up with those prototype processes and prototype products. Often, the users will share that information because if the equipment is improved, the user will not have to bear the costs associated with the modification. As mentioned earlier, owners can be sources of innovations—particularly large, high-stakes owners, such as the U.S. Air Force. The issues they are facing in rebuilding damaged housing or building new houses for new deployments and base realignments are creating intense needs for better, more efficient, systems. They are going to be a source of innovation because they are raising the bar higher and higher. They are telling architects, engineers, and builders that building a thousand houses cannot take 12 years or even five years, it has to be done in a year and a half. That raises the bar.

My research team at MIT found that the rate of innovation and the implementation of innovation increased as the owner’s expectations went up. When an owner says, “I know it is going to be difficult, but I want this pharmaceutical R&D lab built in nine months,” most of the builders say, “I can’t do that so I am not even going to bid on this project.” But a couple of builders will step forward and say, “I think I can do it if you will let me try this, that, and the other thing.” If the owner’s requirements are high enough, innovation will happen. The benefits will accrue to the different parties despite the risks, especially if there is an acknowledgment of risks on the owner’s part.

To summarize, from an owner’s point of view, improving the quality, cost effectiveness, and availability of housing in the United States is critical. PATH’s objective is to leverage the existing opportunities or existing assets in the housing industry, including commercial, government, and academic. To accomplish this, PATH needs to understand the distribution of the benefits, the distribution of the costs, and capabilities of the various sectors.

Another element of a program to advance technology—and this is where Operation Breakthrough and a lot of other previous programs by the federal government did not focus—is to look at how to create a sustainable momentum. The objective should not be to fund this program indefinitely, but to develop a set of capabilities, approaches, and assets, which can be intellectual assets as well as physical assets, that will sustain innovation in the housing industry. There needs to be a long-term approach, not just a year-to-year approach.

DISCUSSION

MR. EMRATH: When you talked about insurance incentives as a leverage point noting that an insurance company might give the owner a cost reduction if the home was safer, do you have an example of where that has occurred?

DR. SLAUGHTER: In industry there is disaster insurance, which is now being offered to owners of large commercial properties, as well as occupants of commercial properties. The idea is that if you are in a high-risk industry, or if you are in a high-risk location, that you would be able to buy insurance. One part of the discussion, but I don’t know that they have moved forward on it, is whether certain characteristics of buildings would lower the insurance rate associated with the natural or man-made disaster insurance.

So, for instance, if you had a “hardened” building that protects against damage from a bomb, your insurance rate would be lower because the probability of damage to the property and injury to occupants would be reduced.

MR. WEBER: Just to expand on that, the Institute for Business and Home Safety, which is spearheaded by the insurance industry, does offer guidelines for what they call “fortified for safer living” homes, and many of their members offer discounts for meeting those guidelines.

MR. ENGEL: Usually the insurance industry says we need more data when you ask for a discount on home insurance. It has been one of the most difficult things HUD has tried.

I think some of the structure discussed in the presentation is absolutely right, but within the context of a homebuilding industry, it doesn’t work. In commercial industry, yes, if someone is building an office building, he has very specific requirements. That is not the case in homebuilding.

DR. SLAUGHTER: In some cases you have a very concentrated large owner, like the Air Force. In that case, they do have a very specific set of demands. You have somebody who owns and leases apartments. They may also have a specific set of demands and they may be looking particularly at operation and maintenance costs.

You are right. When you look at the majority of single-family homes and non-rental properties, there is a diffuse demand and a variation and heterogeneity in the demand. Yet, we continue to build homes and they sell. Part of the risk that homebuilders take is the heterogeneity of demand. They attempt to predict what it is and what is going to be important to a potential buyer.

For example, remember when “great rooms” were the big style and a new house had to have this great big room. The builders had to guess what proportion of their potential buyers were going to want a “great room” and build houses that have them. Then there was a change in preferences to smaller, cozier, but open plan layouts. Shift in demand becomes a very high point of risk for builders, particularly if they are building in advance of their contact with the owners. In Japan and in Finland, there has actually been a very interesting shift in terms of the communication of the owners’ needs to the builders. In some cases the consumers say, “This is what I want before you build my house.” There are a lot of large-scale builders in the U.S. who do that right now.

MR. HODGES: I would like to speak to that. Builders have become very nimble at meeting very specific customized requirements of their customers. We call it mass customization. My company now has 3,000 floor plans and we have 150 different granite countertops from which the consumer can choose. Consumers are very explicit about what they want and builders have to meet that demand. However, consumers do not demand technologies that improve performance but do not alter the appearance or size. Builders have become quite nimble at meeting a very diverse and very exquisite set of fit and finish demands of the consumer. The consumer doesn’t come in saying, “This is the type of roof shingle I want” or “This is the HVAC system I want because it does the following things.” They are uninformed. Were they to be informed, believe me they would ask and we would find a way to deliver it. So, I think the capacity is there. It is just the countertop the consumer wants. That is what they are interested in and they ask a lot about it.

MR. EMRATH: One of the points is that appearance is really important. If it looks nicer, consumers definitely will drive that innovation. The issue here is about something where the benefit isn’t so obvious.

DR. SLAUGHTER: But there are ways in which the builder can present those questions to the homeowners. Not asking which HVAC system they want leaves the definition of the choices up to the homeowners, since they have no idea what their choices are and the effect of each possible choice. But if the builder says: “This is the initial cost for each one of these air conditioning systems and this is what the long term operating costs are,” they are going to be able to make their choice.

Consumers will be able to make those choices if there is an analysis or ordered logic. Builders can provide buyers with up to 15 different attributes and then list the different levels of importance for the attributes or performance on those different attributes. The consumers will consistently sort on those specific attributes to show exactly what their relative priority is and their price points. Builders have offered the opportunity to choose fit and finish, but have not offered that opportunity for all the systems.

There are some people who had recently built their houses on the Gulf Coast to much higher standards than required by the building code. It was an option that was offered by their builder. The result is that their homes were the only ones left standing. If improved performance is offered as an option, the owners will be able to make a choice based on their own values and priorities.

MR. HODGES: I agree with that but there are lots of problems. For example, when estimating the long-term operating costs there are a lot of assumptions regarding future costs for energy, labor, and materials. The prospective owners, sometimes for a good reason, may not believe what someone tells them about how much they will save.

DR. SLAUGHTER: That was the case when the appliance ratings came out. If you have a teenager and they stand there with the door to the refrigerator open, the efficiency rating on that refrigerator has no meaning. The way a system is used may eliminate any advantages to an innovative

design.

MR. HATTIS: We are really touching the fringes of a very important issue related to the housing industry. I mean, the PATH goals relate to improved performance in a variety of areas that are somewhat abstract, like durability, safety, welfare, and affordability, not just in terms of the initial performance of the house, but over the life of the building. We are dealing with an industry that, as we have heard from the examples of countertops and so forth, is primarily product-oriented, not performance oriented and oriented to first cost, not life-cycle cost and benefit.

What PATH has to do in this area is change those two ingrained characteristics of the housing industry and if that won’t happen, then PATH will probably have marginal success. If that happens, PATH will have remarkable success.

DR. SLAUGHTER: Large-scale builders, who build the houses, sell them to the new owners, and then they end their relationship with the owners. However, there is also the huge population of small residential builders, who will work on a house for multiple generations. For example, I was living in a house that was built in the early 1700s in eastern Pennsylvania. Four generations of carpenters, who lived in that neighborhood, had been working on that house. There are builders that focus on the first and initial costs and there are builders that focus on the long-term costs. These different populations respond to innovation in different ways.

MR. CHAPMAN: Two comments: (1) Do not forget that builders are generally very market driven; and (2) the whole system from financing, appraisals, and resales, is set up to deal with upfront-cost and not with long-term sustainability.

On another matter, the problem we have with technology diffusion in this industry is with the supplier. The supplier dictates what can and cannot be done. I am in Santa Fe, New Mexico. There are products that are simply not available to me. There are also products that are available today that will not be available tomorrow. If I make a technology jump with a new widget for a home to make it perform better, it may be available for the next six months and after that it is no longer available. I am forced to go back to using something that I used previously because it is the only thing I can get. That is a widespread problem in the housing industry. When it comes to barriers, we need to consider the supply chain as a key part of the process.

DR. SLAUGHTER: There are ways to address that problem. Other industries have adopted a just-in-time supply strategy, to streamline the supply chain and eliminate the need for large warehouses with inventories that need to be redistributed. Through Internet search engines, builders can deal directly with the manufacturers. If a manufacturer knows that Albuquerque is a great place for its product, maybe it will devote resources to Albuquerque; however, they may not know it if they go through a distributor in Texas.

MR. KASTARLAK: I think there is more to that issue. In your flow chart of the innovation process (Figure 4.1), the role of the architect is almost an afterthought. That shouldn’t be. Why? Because I don’t know how doctors or lawyers would feel if they were not in control of their own profession. Architects in this situation are not in control. Yet architects have introduced many innovations.

Beyond that, you pointed out the issue of externalities. Decisions are made because people like living certain ways. Some people can afford whatever they want. PATH should concentrate on the more difficult issues where the people cannot afford many options, but are looking for a decent home.

We have to follow the money trail to learn where the money is going, why decisions are being made the way they are, and then take measures to affect the process.

There should be a push for radical solutions that maximize the public benefit and help housing become more cost-effective and sustainable. In other words, PATH should create a brand that will be recognizable by every home buyer as representing improved value.

FIGURE 4.1 Innovation value-added chain.

DR. WHITE: If you were sitting where the PATH staff is now, what advice would you give them about how to take the ideas that you presented and turn them into steps that the PATH program can take now and in the future?

DR. SLAUGHTER: I think that various touch points I have listed in Table 4.1 offer significant opportunities. PATH needs to understand and focus on the incentives that motivate all of the parties in the partnership. Manufacturers have an incentive to get their product out to customers. PATH can leverage those basic incentives for any commercial organization to make money most effectively. Universities and government labs have an incentive to get their research widely known to prove that they have an impact and provide a benefit, and to prove that they have been using their resources effectively. If PATH can leverage those internal organizational incentives it will be able to effectively advance technology in housing.

By knowing what all of the incentives are and what resources are available from all sources, PATH can facilitate the process of bringing them together. Facilitation is a very appropriate role for the federal government.

MR. HODGES: I think the draft strategy is excellent. The list of barriers is fairly complete, but I could add about eight more. Being a homebuilder, I recognize that it is an industry that has hundreds of years of tradition unhampered by progress. That is largely because builders do not accept responsibility for building sciences and technological advancement. We don’t see it as part of our job.

If you look at the 20 largest homebuilders, there is only one that has a research and development component. We all look admiringly at Pulte Homes, because it has a building sciences component in the organization. K. Hovnanian is about to launch one in emulation of Pulte. For the top 100 homebuilders, purchasing is the innovation gateway to the organization. It is where decisions about what to buy and how to build homes are made.

There is not a purchasing agent for homebuilders in the U.S. who cares about innovation. They care about dollars per square foot, bricks and mortar costs, and doing it fast because they have lots of communities to set up and homes to build. Their bonus is based on bricks and mortar costs. To them, innovation creates more work because they need to change the construction documents. If the innovation is a different roof shingle installed the same way, then they will use the new roof shingle; however, if it involves a change at the construction site, the purchasing guy is not interested.

Until the homebuilding industry becomes committed to the notion that research and development is partly our responsibility, we are not likely to promote innovation or force it into our organizations. That is a massive barrier that did not make the list. I think it needs to be understood because we have got to get homebuilding companies to understand that they have a role. It is not just the purchasing agent’s job to decide what materials we use to build our homes. Builders need to have a research and

development component.

MR. PETERSEN: For me at Pulte, it has been a four-year battle just to get to where I am within the company because there is no financial incentive to do R&D. Pulte would not have a building science component if Bill Pulte did not understand the long-term benefits. The building industry is driven by very short term financial outcomes.

R&D is a difficult sell and it is a struggle day after day to bring R&D into homebuilding because consumers do not want pay for it. The incentive within Pulte is long-term by differentiating the brand. Home buyers will look for a Pulte home because we differentiate ourselves by using better products and by having better processes, but that will take years to accomplish.

MR. HODGES: The division president, whose bonus is based on return on invested capital, is not going to spend money on R&D.

When you make the division use better products and better processes that cost more money you need to get a bulletproof vest. I convinced the company to invest in a building sciences operation, which we are about to launch.

MR. PETERSEN: It is a daily struggle, but I am having some success with getting the voice of the customer back to the suppliers. That is what I am really focusing on now. I have the clout with the suppliers because I can deliver a market for 50,000 or 60,000 homes a year if they develop the right product. That is where I am really starting to see the impact, because it does not cost a lot of money to be the voice of the customer back to those suppliers.

I am starting to get the real bang for the buck for the company by influencing what the manufacturers develop. We are able to influence what our supply chain develops for us to ensure they are going to serve the long-term interests of the home buyer.

MR. HODGES: My short-term strategy is that my company is going to build 50 million square feet of housing in 2006. I went to my company and said I will find technologies that will save $1 a square foot. Let me have a couple million dollars and I will get you $50 million. Now I have their attention. It wasn’t about building better houses with sustainability. It was about saving a dollar a foot and we will do it.