5

Implementation

CHAPTER SUMMARY

Chapters 3 and 4 reviewed several alternative methods for creating and distributing a funding pool to reward performance by health care providers who serve Medicare beneficiaries. This chapter addresses major implementation issues that must be considered when new payment schemes designed to create incentives for improved performance by multiple types of health care providers are introduced. This chapter also considers key goals and objectives that should influence the process and pace of implementation of new pay-for-performance programs within different health care environments.

This chapter highlights some procedural and technical issues that might be encountered if a Medicare pay-for-performance program were initially implemented in small steps (such as by care setting or by geographic region) and were subsequently made comprehensive and national in scope:

-

Steps in implementing pay for performance and their timing

-

The overall timing of implementation

-

The nature of participation in payment for performance

-

The unit of analysis and reporting

-

The role of health information technologies

-

Statistical issues

Some lessons can be learned about these issues from existing pay-for-performance efforts, even though many such efforts are still in their infancy. As experience is gained, additional lessons will be learned, and adjustments should be made in Medicare’s program accordingly.

STEPS INVOLVED IN IMPLEMENTING PAY FOR PERFORMANCE AND THEIR TIMING

Because a pay-for-perormance program depends on many inputs and the creation of new capabilities, the time needed to implement such a system is an issue that requires careful consideration. Before performance-based rewards can be offered, measures must be developed and tested (as discussed in Chapter 4 and the Institute of Medicine [IOM] report Performance Measurement: Accelerating Improvement [IOM, 2006]). Next, data reflecting these measures must be collected and audited, and then distributed to providers for review and feedback. The performance data must then be publicly reported before the final step of paying providers for their performance can be implemented.

Data Collection and Auditing and Provider Feedback

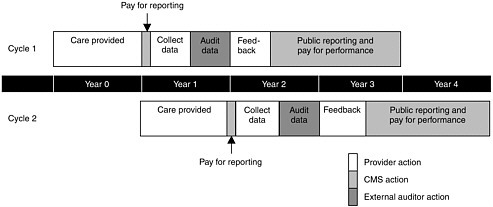

Following the development and testing of performance measures (which as noted was discussed in detail in the Performance Measurement report), the next step toward pay for performance is data collection. Data reflecting how well each provider performs on a given metric can generally be gathered from administrative claims, surveys, or medical chart review (in order of the lowest to highest time and cost burden imposed on providers). As discussed in Chapter 4, trade-offs must be made because data relating to the most useful measures are often the most difficult to collect. After being collected, the data need to be audited by an independent body to ensure their validity before they are used to determine relative performance and payment. Data collection and audit may take 6 months even under an aggressive timetable. Once the data have been audited, the results should be shared with providers, each of whom should have the opportunity to provide feedback. Even on a tight timeline, feedback may initially take up to another 6 months to complete. On a less aggressive timetable, these essential steps could initially take up to 2 years. After the first cycle of reporting had been completed, however, the time required for feedback could be reduced to less than 1 month (see Figure 5-1). The entire timeline should be condensed wherever feasible without imposing an undue burden on providers; differences in ability by various provider types should be recognized.

Public Reporting

The committee strongly endorses transparency and accountability in health care to better inform all stakeholders, especially patients, about the performance of the care delivery system. To this end, the committee believes that information reflecting how well health care providers perform on spe-

FIGURE 5-1 Example of initial timeline from data collection to pay for performance.

cific measures must be shared with the public and that such public reporting should be a requirement for performance-based payment. Many proponents of public reporting believe this strategy in itself can be a useful tool for improving all aspects of quality, regardless of its association with rewarding performance. To date, the limited evidence presented in the literature is mixed, but overall it does suggest that public reporting can have an impact on provider behaviors and improve quality (Marshall et al., 2000; Hibbard et al., 2005; Jha and Epstein, 2006; Robinowitz and Dudley, 2006).

At the same time, public reporting could have unintended adverse consequences. For example, some providers might avoid sicker patient populations, and others might choose not to participate in Medicare if public reporting on performance became a condition for participation. Notwithstanding the literature that argues otherwise, some low-performing providers might fear that public disclosure of performance data would attract malpractice claims in which the data could be used against them (Werner and Asch, 2005; Kesselheim et al., 2006).

Current Public Reporting Efforts in Medicare

Through the development of the Compare websites by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS),1 many providers are already publicly reporting performance data. In 1999, the Medicare Personal Plan

Finder began comparing the performance of health plans participating in the Medicare+Choice (now Medicare Advantage) program. In 2003, CMS began collecting and reporting data for nursing homes, home health agencies, dialysis facilities, and hospitals. The Medicare Prescription Drug Plan Finder, which allows beneficiaries to compare the premiums and benefits of the various prescription drug plans, was made available in 2005. Beginning in 2006, CMS initiated voluntary reporting for physicians.

Health plans, nursing homes, home health agencies,2 and dialysis facilities must all report on some services to CMS to receive payments. Reporting is voluntary for hospitals and physicians. In the case of hospitals, however, a small portion of payments—0.4 percent in 2005 and 2 percent in 2006—is withheld from those that do not report as delineated in the Deficit Reduction Act of 2005 (Public Law 109-171); the result has been more than 94 percent of hospitals reporting (CMS, 2006). It is reasonable to suggest that the pay-for-performance approach proposed in this report could be implemented more expeditiously in those settings for which CMS has already been collecting and publicly reporting performance-related data.

Usability

While a number of performance reports from both public and private programs are already available, they are often not particularly helpful to or used by consumers. In the future, not all measures that may be publicly reported to assist consumers will be relevant to pay for performance, and not all measures used in pay for performance will be meaningful to consumers. However, the committee believes that to enhance the integrity of the system, all measures of performance affecting payment should be publicly available. Data must be presented in a fashion that is easy to understand and has meaning for consumers (Hibbard et al., 2000, 2002; Vaiana and McGlynn, 2002). The growing evidence base that explores the types of information and formats the public finds most comprehensible should be consulted to inform public postings. Clearly, as recommended in the Performance Measurement report (IOM, 2006), more research is needed to identify the formats most informative for consumers, particularly as the movement toward web-based venues for the presentation of information continues. Multiple reports may need to be developed for different audiences.

Pay for Public Reporting

As noted in Chapter 4, a major area of concern is the magnitude of the burden that might be imposed by data collection, review, and report-

ing. The costs associated with collecting and reporting data may be significant, especially for small providers such as independent physicians. A common suggestion for easing the burden of data collection and reporting is the use of health information technologies. As discussed later in this chapter, however, many barriers to the adoption of such technologies exist, including a lack of technical expertise, little agreement on software standards, and cost.

Recommendation 6: Because public reporting of performance measures should be an integral component of a pay-for-performance program for Medicare, the Secretary of DHHS should offer incentives to providers for the submission of performance data, and ensure that information pertaining to provider performance is transparent and made public in ways that are both meaningful and understandable to consumers.

There are two views on how the burden of reporting should be treated. Some argue that the costs associated with collecting and reporting data should be considered a portion of the investment providers must make to be eligible for rewards. Others believe that providers should not be forced to bear these costs until there is convincing evidence that pay for performance can enhance performance and that enhanced performance will lead to significant rewards.

The committee proposes that, initially at least, providers receive payment for collecting, submitting, and reviewing the performance-related data that will be publicly reported and used in the pay-for-perormance program. Financial incentives for the initial submission of data would help defray providers’ costs for coding and collecting performance data that cannot be obtained from existing administrative or claims records. Such incentives might also reduce provider opposition to the new system.

The committee believes the pool of funds supporting such incentives should be modest, comparable to those resources used to provide incentives for the voluntary reporting of performance measures by acute care hospitals, and that these payments should end when the collection and reporting of performance measures become routine. Because the committee envisions the continuous development of new and more complex metrics, focused on measures of efficiency and shared accountability, reporting incentives could correspondingly be redirected to new areas that are more complex and difficult to measure. This approach would ensure that providers are not paid merely for the submission of routine data, but are offered incentives that encourage and reward public reporting in areas that can serve as potential levers to improve overall quality. The rewards associated with public reporting should be a small fraction of those devoted to rewarding performance.

Pay for Performance

Only after data have been publicly reported for a predetermined period of time should providers be rewarded based on their performance. This lag time would give providers a chance to become comfortable with the reporting system. Providers would also gain an understanding of how their rewards were derived because during this interim period, CMS would send them estimates of what those rewards would have been had the data affected their payments. Moreover, consumers would have the opportunity to respond to the data by switching providers. Under this timetable, pay for performance based on performance measures available for collection at the start of the program would take place during the second year of implementation (see Figure 5-1). It is important to note that this entire process—from data collection to pay for performance—would be a continuous one. While providers were being rewarded on the basis of old performance data, new data would be collected, distributed, and reported to begin the next cycle of pay for performance. Thus the data used to provide the initial rewards during year 2 would be reflecting performance from year 0 and would have been collected and audited during year 1; data for the next cycle of pay for performance would be reflective of care in year 1 (see Figure 5-1). While rewards initially would be based on data that were 2 years old, over time this lag could be shortened as CMS developed better data collection systems (see the discussion later in this chapter regarding health information technologies) and other strategies.

OVERALL TIMING OF PAY-FOR-PERFORMANCE IMPLEMENTATION

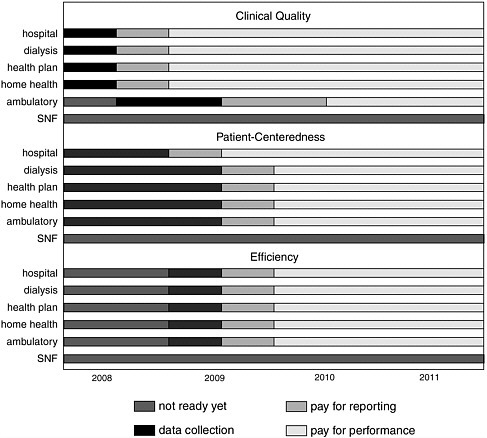

As described in Chapter 4, the committee recommends rewarding providers in three domains—clinical quality, patient-centeredness, and efficiency—as an overarching principle. The committee identified two overall timing options for implementing pay for performance across these three domains. An example of how these options could occur in the ambulatory setting is presented in Box 5-1.

Option 1:

Phased Implementation

The first option would be phased implementation, in which pay for performance would begin in each domain as measures became available. Because measures are less developed in some domains than in others, however, there are problems with this approach. For example, the amount distributed from the reward pool would be limited if measures were lacking for one dimension, such as efficiency. Without distribution of the full reward pool, incentives might be inadequate to change provider behavior.

|

BOX 5-1 Example of Phased and Delayed Implementation in the Ambulatory Setting In the ambulatory setting, a phased implementation could follow the timeline presented below, based on the state of measures in each domain:

In this example, pay for performance on clinical quality and patient-centeredness would begin in 2010. Pay for reporting (smaller amounts than the rewards for performance) would be implemented in 2008 to help defray the costs of data collection. The collection of these data has begun to some extent through CMS’s Physician Voluntary Reporting Program. Rewarding on measures of efficiency would not begin until 2012, with pay for reporting in 2010. However, one option for rewarding on resource use during the intervening period would be to give physicians meeting certain thresholds on both clinical quality and patient-centeredness measures an additional reward if they, by some crude measures, were within the most efficient third of providers. The most efficient |

Option 2:

Delayed Implementation

The second option would be to delay implementation of pay for performance until a robust set of performance measures had been developed for all three domains. Pay for reporting would begin as measures were developed in each domain and data collection began, but pay for performance would be delayed until after public reporting for all three domains had commenced. If the program’s funding mechanism started when performance

measures were being developed and the rewards for reporting were less than collected funds, a larger pool would accumulate for initial performance rewards. This delayed implementation approach would ensure that provider behavior did not overemphasize one domain over the others and that rewards would be distributed only for care that was of high clinical quality, patient-centered, and efficient. The disadvantage of this option is that pay for performance might not begin for many years, and the sense of urgency on this issue might be dissipated.

|

third of providers could be calculated from standardized costs for Medicare Parts A and B. These costs could be derived from national prices, such as an average payout per unit on the resource-based relative value scale. This method of rewarding efficiency would be phased out upon the development of more sophisticated measures. In contrast, delayed implementation of pay for performance in the ambulatory setting might occur on the following timeline:

Under this option, physicians would receive payment for reporting on clinical quality and patient-centeredness measures beginning in 2008. Reporting on efficiency measures would not be rewarded until 2010. Rewards for all three domains on the basis of performance would begin in 2012. NOTE: AQA = Ambulatory care Quality Alliance; CAHPS = Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems. |

Conclusion

The committee concludes that phased implementation (option 1) is the preferred approach because it recognizes the urgent need to improve the health care system as quickly as possible. Efforts described in this report to make available a large number of measures of clinical quality and the movement toward better characterizing patient experiences are representative of the momentum in both the public and private sectors that argues for earlier onset of pay for performance. The committee believes this momentum should be captured.

PARTICIPATION IN PAY FOR PERFORMANCE

Two key topics related to participation in pay for performance deserve attention: (1) the nature and pace of the phasing in of payment for performance in different health care settings, and (2) the extent to which participation should be voluntary or mandatory.

Phasing in Participation for Different Settings

Initial Implementation

The committee concurs with MedPAC’s rankings for initial participation in pay-for-performance programs: (1) Medicare Advantage plans, (2) dialysis facilities, (3) acute care hospitals, (4) home health agencies, and (5) physician practices (MedPAC, 2005a, 2006). Medicare Advantage plans, dialysis centers, and hospitals are positioned to implement pay for performance now because of the availability of performance measures, the reliability of data, and the fact that the necessary supporting infrastructure is in place. Home health agencies, followed by physicians, would be next to be expected to participate in pay for performance. For an implementation timeline, see Figure 5-2.

Exclusion of Other Providers

The committee believes that eventually, all providers should be included in Medicare’s pay-for-performance program. At this time, however, adequate performance measures do not exist for certain institutional providers, such as ambulatory surgical centers, clinical laboratories, rural health clinics, and rehabilitation hospitals, and for certain professionals, including nurse practitioners, occupational therapists, physician assistants, and pharmacists. Once adequate performance measures have been developed, the burden of collecting and reporting on these measures has been made man-

FIGURE 5-2 Implementation timeline for pay for performance.

ageable, and the necessary infrastructure has been put in place, these providers should be brought into the system.

Skilled nursing facilities, not among the institutional providers considered ready for pay for performance as listed in the previous section, deserve special mention. Medicare pays for a specific type of nursing home care provided by these facilities. This specialized care, which represents about one-quarter of all care provided in nursing homes (MedPAC, 2006), follows a medically necessary hospital stay of at least 3 days, is short-term, and is characterized by the use of skilled nursing or rehabilitation services in an inpatient setting.

The committee had several reasons for concluding that it would not be appropriate to reward skilled nursing facilities for performance at this time. First, only 3 of the 15 measures found in the Minimum Data Set—the publicly reported set of measures used to assess nursing home performance— are relevant for short-term stays of the sort paid for by Medicare. Second,

these measures (delirium, pain, and pressure ulcers), while important, capture the experiences of only a small portion of beneficiaries covered by Medicare payments to skilled nursing facilities. Third, the data collected do not necessarily capture the quality of care delivered by the facility, as these measures do not accurately reflect the patient’s condition upon admission and may reflect care given during the hospital stay (MedPAC, 2005a, 2006). Therefore, the committee concludes that before pay for performance is implemented in skilled nursing facilities, more research is needed to permit better attribution of care. CMS is planning to launch a pay-for-performance demonstration in nursing homes by the end of 2006, which should provide valuable insights for the design of an appropriate pay-for-performance program for nursing homes (The Commonwealth Fund, 2006).

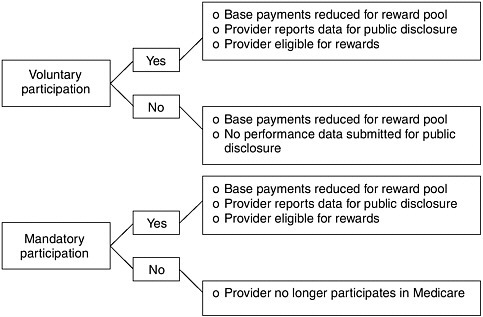

Voluntary Versus Mandatory Participation

Participation in pay for performance may be either voluntary or mandatory. “Participation” involves collecting and submitting to the payer the data needed to construct performance measures, which in turn makes providers eligible to receive financial rewards if they have performed well. With voluntary participation, the individual provider can decide whether to gather and submit performance data and be paid in part on the basis of performance. Under mandatory participation, all providers are required to take part in the system. Mandating participation could burden those providers who would have a difficult time mobilizing the resources required for data collection and reporting, particularly those not closely associated with institutions who may lack access to health information technologies that can ease the burden of those activities. The reliability and validity of data for small providers may also be difficult.

Most private-sector pay-for-performance programs, which tend to focus on physicians, are voluntary. A recent survey of such programs found 91 percent to be voluntary (Baker and Carter, 2005). The propensity toward voluntary programs appears to be related to the heterogeneity of physician practices with respect to their size, specialty focus, location, and use of information technology. Some fear that making such a program mandatory could be too burdensome for certain types of providers, such as small group practices and practices that serve only a handful of a health plan’s members. Indeed, programs often differentiate among practices in their requirements for participation. For example, to ensure statistical accuracy, some programs require a minimum volume of patients or a specific ratio of patients treated per physician before a provider is allowed to participate; others permit only providers who have met quality or efficiency thresholds to enroll (Baker and Carter, 2005).

While the experience of the private sector is instructive, several additional considerations are relevant to participation requirements for a Medicare pay-for-performance program. First, Medicare is the provider of primary insurance for virtually all of the elderly and disabled. Therefore, if policy makers want to ensure that all beneficiaries have the opportunity to receive services from providers with incentives to improve all aspects of quality, participation should be mandatory. Second, Medicare beneficiaries constitute a much larger portion of most providers’ business than do the members of any single commercial plan, implying that the burden and minimum volume requirements faced by private-sector pay-for-performance programs should be of less concern. Third, as discussed above, many categories of providers already submit performance data to CMS; this is required for some types of providers, voluntary for others, and not expected at all for still others. If all or nearly all providers of a certain type are already submitting the inputs needed for a pay-for-performance program, it would appear sensible to make their participation mandatory. The committee assumes that more measures will be collected in the future for these providers and expects these measures to be incorporated into pay-for-performance programs. Finally, the committee proposes that initial funding of pay for performance be taken out of base payments, which means that the base payments for all Medicare providers, whether participating or not, will be reduced to generate resources needed for the incentive reward pool. In the absence of mandatory participation, some providers might argue that they should not have their base payments reduced if they have no chance of being rewarded for good performance (see Figure 5-3).

Option 1:

Mandatory Participation

One option for participation in pay for performance is to require that all Medicare providers submit data to CMS for public reporting, and thereby become eligible to receive rewards related to these performance data. Participation would be required as soon as a minimum set of measures was available for each category of provider; those who did not submit the required data to CMS would no longer be considered Medicare providers. Requiring participation could catalyze an accelerated national effort toward performance improvement. While such a stark mandate might be burdensome to CMS, the vast majority of hospitals, home health agencies, dialysis facilities, health plans, and skilled nursing facilities already report some data to CMS that are publicly disclosed. Mandatory participation for physicians and other small providers might be quite challenging if required in the next few years, however.

FIGURE 5-3 Outcomes of voluntary and mandatory participation.

Option 2:

Voluntary Participation

Allowing providers to choose whether to make the investments necessary to participate in pay for performance represents a more cautious approach and one that would engender less stakeholder resistance. While voluntary participation would be less burdensome to providers who chose not to participate, however, it would undermine the current sense of urgency regarding the need to improve performance and would not capitalize on CMS’s public reporting efforts. It is also possible that only those providers who were confident that their performance would be rewarded would join the program, which would do little to raise overall performance. Nonparticipants would argue that their base payments should not be reduced to provide the resources for a program from which they could not benefit.

On the other hand, voluntary participation would reflect some of the underlying realities of the diverse provider community. Many providers have small volumes of Medicare business and have limited capabilities with regard to information technologies and data collection and analysis. This is true for some hospitals and other institutional providers, as well as for smaller physician offices. Allowing providers to opt out of a pay-for-performance program, at least until all of the issues involved have been resolved and the effectiveness of the program has been demonstrated, may be a bow to reality.

Option 3:

Combination of Mandatory and Voluntary

A third option is to mandate pay for performance among those providers for whom the performance measures and data infrastructure needed to support an incentive-based payment program are available. Providers whose participation could begin immediately with relatively few barriers to implementation are Medicare Advantage plans, dialysis facilities, hospitals, and home health agencies.

Participation for other providers could be phased in when appropriate. Although the necessary measures and data are not yet available for skilled nursing facilities, these providers are already publicly reporting some data to CMS, demonstrating that they do possess the infrastructure necessary for pay for performance. Thus these facilities are in a position to be subject to mandated participation as soon as appropriate measures are available. Measures for other institutional providers, such as clinical laboratories, ambulatory surgical centers, and hospices, are even further behind; the measures are limited, and CMS has not yet developed public reports for these providers. Participation by these other institutions could be mandated given the development of performance measures and positive assessments of these institutions’ capabilities to report data publicly.

Many large physician organizations are also ready to participate now in pay for performance. The threshold size of organizations required to participate would be determined by the Secretary of DHHS. Voluntary participation by individual physicians and small physician organizations during the initial phase of pay for performance could improve the acceptance of performance-based rewards by allowing physicians time to develop both confidence in the measures and the structural supports necessary for participation.

Conclusion

The committee recognizes the importance of establishing the expectation that all Medicare providers will participate in public reporting and pay for performance. However, it also recognizes that the pace of implementation, the breadth of measure sets applicable to specific types of providers, and the size and distribution of reward pools will need to vary depending upon the availability of measures and the organizational and technological challenges faced by different providers in carrying out performance measurement and reporting. Efforts should begin immediately to develop and test performance measure sets that fill existing gaps so that all providers can also begin to participate in public reporting and pay for performance as soon as possible.

Some physicians may face greater barriers to implementation than other providers and should therefore be considered separately. CMS should immediately develop and implement a strategy for ensuring that virtually all physicians participate—on at least some measures—as soon as possible. This strategy will need to be sensitive to differences across specialties in the availability of performance measures and the diversity of information systems and operational supports in different practice settings. Financial incentives adequate to ensure early and broad physician participation in the submission of performance measures and public reporting should be employed. Consideration should be given to benefits such as linking accelerated payments or the physician annual payment update to rewards to provide an incentive for public reporting in the same manner that was used with hospitals, as described in the Deficit Reduction Act of 2005. Initial measure sets for pay for performance may need to be limited in some physician settings. In establishing the size of the reward pools, CMS will need to strike a balance between providing financial incentives sizable enough to lead to near-universal participation and recognizing that initial measure sets are narrow, presenting an incomplete picture of a provider’s performance.

The transformational changes in the delivery system envisioned in the IOM’s Pathways to Quality Health Care series of reports will depend upon both the adoption of longitudinal measures of quality that cut across settings and the provision of substantial payment rewards. The strategy used to implement pay for performance should involve moving as soon as practical from the current relatively narrow, provider-specific approach to a more comprehensive, longitudinal set of measures and substantial rewards that encompass all Medicare providers. A monitoring system should be part of the implementation process to inform future decisions about the pace of expansion of the performance measure sets and make it possible to determine whether the voluntary approach initially recommended for physicians is achieving the goal of near-universal participation.

Recommendation 7: The Secretary of DHHS should develop and implement a strategy for ensuring that virtually all Medicare providers submit performance measures for public reporting and participate in pay for performance as soon as possible. Initially, measure sets may need to be narrow, but they should evolve over time to provide more comprehensive and longitudinal assessments of provider and system performance. For many institutional providers, participation in public reporting and pay for performance can and should begin immediately. For physicians, a voluntary approach should be pursued initially, relying on financial incentives sufficient to ensure broad participation and recognizing that the

initial set of measures and the pace of expansion of measure sets will need to be sensitive to the operational challenges faced by providers in small practice settings. Three years after the release of this report, the Secretary of DHHS should determine whether progress toward universal participation is sufficient and whether stronger actions—such as mandating provider participation—are required.

While some small physician organizations and individual physicians are prepared to participate in public reporting and pay-for-performance initiatives, many others will require guidance, technical assistance, and additional infrastructure to make critical transitions in adopting quality procedures and information systems that can enable them to engage in these initiatives. CMS will need to monitor and evaluate the transition phase to identify and share lessons learned at the level of small and individual practices. A target strategy could be used to establish clear goals that could guide this process and to assess progress and unexpected consequences that emerge as pay for performance is phased in over time. Such a strategy could be especially useful for implementation among physicians. In the first phase, for example, only a small percentage of individual physicians or those in practices with only a few physicians might be expected to report data and participate in a performance incentive program. After a year or two, a larger number of physicians might be required to report data to CMS. Another possible target might be for physicians providing more than half of their care to Medicare beneficiaries to submit data and participate in the pay-for-performance program. Performance could also be based initially on a narrow set of measures, preferably ones aligned across public and private payer programs. Physicians could be phased in by the number of areas of specialty care, by the number of states, or by some other selection criteria, as illustrated in Table 5-1. Targets would not be mutually exclusive.

Participation by Specialists

The committee recognizes that specialty care is an integral part of health care: 41.5 percent of visits nationally are made to specialists (NCHS, 2005), and two-thirds of physicians are classified as specialists (U.S. GAO, 2003).3 Pay-for-performance programs are, however, limited to those providers for whom there are performance measures, and the measures presented in the starter set in Chapter 4 (see Table 4-1) for the most part do not pertain to specialists. The IOM’s Performance Measurement report found that while

TABLE 5-1 Illustrative Targets for Phasing in Pay for Performance for Physicians

|

Year |

Physicians (%) |

Medicare Beneficiaries as 50% or More of Patient Population (%) |

Specialty Areas (number) |

States (number) |

|

1 |

10 |

100 |

3 |

5 |

|

2 |

30 |

75 |

10 |

12 |

|

3 |

50 |

50 |

20 |

25 |

|

4 |

75 |

30 |

40 |

38 |

|

5 |

100 |

10 |

60+ |

50 |

many measures exist for specialists, such as those developed for thoracic surgeons, these measures need further vetting before being considered robust enough to be used at the national level for payment based on performance (USPSTF, 2006). The lack of specialist measures is a critical gap in performance measures. As mentioned in Chapter 3, pay for performance could help specialists and others accelerate the development of performance measures. Efforts should be made to ensure that newly developed measures are subject to equally rigorous testing for reliability and validity. The committee concludes that measures for specialists should be addressed with the utmost urgency and, once available, be included in pay-for-performance programs.

UNIT OF ANALYSIS AND REPORTING

In designing a pay-for-performance program, it is necessary to decide whether performance measures will be collected for and rewards paid to individual providers or groups of providers who together are responsible for a patient’s care. As discussed in Chapter 4, the committee believes it to be unavoidable that rewards will be distributed initially by setting of care. In other words, rewards will be distributed to health plans, dialysis facilities, hospitals, home health agencies, skilled nursing facilities, and physician offices. Ultimately, the committee envisions that performance will be measured by following patients across time and across the various settings in which a patient receives care (see Chapter 2).

Implementation will be different for various types of providers. The unit of analysis for most institutional settings has already been defined as the facility itself, rendering the question of payment being made to indi-

viduals or groups of little consequence. On the other hand, rewarding physicians paid under Part B becomes complicated (see Box 5-2).

Virtual Groups

In identifying options for the unit of analysis for physicians, the committee discussed the merits of encouraging the formation of “virtual groups”—groups of physicians who, while not formally connected, would choose to associate with each other in informal ways to promote coordination of care and improve efficiency. This could occur, for example, through patient-determined groups or coordinated use of information technologies. Box 5-3 provides examples of how virtual groups could function to accelerate improvements in care delivery.

Several arguments can be made for encouraging virtual groups. First, performance measures for groups, whether organized or virtual, would be more accurate than those for single physicians or small group practices because the sample sizes would be larger. Second, the ability to compare and discuss clinical quality and efficiency with a number of like-minded providers and possibly share information technology tools could serve to improve overall quality. Third, multispecialty virtual groups could encourage coordination and help overcome the quality deficiencies that arise from poor care coordination among the various physicians treating a single patient.

Many questions need to be addressed in assessing the feasibility of virtual groups. For example, what financial relationships would be required among members? What would the legal structure look like? What would the mechanism be for entering and exiting the group? How could one monitor the impacts as well as the unintended consequences of virtual groups? What would it take to create such groups? Although many such questions must be addressed, the committee supports exploration of the formation of virtual groups.

Promoting Coordination

Health care is often the product of many actors, as patients tend to be treated by more than a single provider. On average, Medicare beneficiaries are treated by 5 physicians during a year. Those with such chronic conditions as chronic heart failure, coronary artery disease, and diabetes see an average of 13 different physicians in a year (MedPAC, 2005b). Patients are also treated in multiple care settings, moving, for example, among physician offices, hospitals, and long-term care facilities. As discussed in Chapter 2, the health care received by Medicare beneficiaries is often fragmented and not well coordinated. This critical problem is thought to result in worse

|

BOX 5-2 Example of Units of Analysis in the Ambulatory Setting Physician offices differ from other settings in part because of issues of sample size. The literature has shown that for measures to represent adequately how well providers are performing, on average 25 cases are needed (personal communication, G. Pawlson, August 3, 2006). Since the committee argues that rewards should be linked directly to how well providers perform based on a composite score for a specific condition (see Chapter 4), a physician would have to see a minimum of 25 patients per condition, referred to as cases, to be eligible for rewards. However, a single primary care physician may not see 25 or more asthmatics or diabetics, and a physician who did not have a sufficient number of cases would not qualify for rewards for that condition. This issue also raises the question of whether rewards will be large enough to be financially meaningful to providers. To address these issues, the committee examined three alternatives for providing rewards at the physician office level. Option 1: Individual Physicians. Under this option, individual physicians with sufficient numbers of cases would be eligible for rewards associated with performance. The care attributable to each physician would be known and could therefore be rewarded appropriately. Because care would be attributable to individual physicians, a shared sense of responsibility could result from this option. However, many physicians do not see enough patients for measures to be reliable, and it is difficult to estimate resource use. Moreover, rewards may be too small under this option for physicians to seriously consider participating in pay for performance. This option also poses the technical problem of attributing patients to physicians (Pham, 2006). |

health outcomes. One way to address this problem is to provide direct and indirect incentives for care coordination. To the extent that pay for performance rewards specific providers for performing at a desired level and care coordination contributes to high-quality care, pay for performance should indirectly encourage better care coordination. Nonetheless, the fragmented nature of care, the increased specialization among professionals, and the inherent difficulty of assigning responsibility for health outcomes may mean that more direct incentives are needed to generate the optimal amount of coordination. To this end, the committee recommends that Medicare encourage beneficiaries and their providers to identify a responsible or accountable source of care. This accountable source of care could take various forms, including (1) the beneficiary’s predominant caregiver (e.g., a primary care doctor, a specialist treating a chronic condition), who would agree to be responsible for the coordination of all of the beneficiary’s care;

|

Option 2: Physician Groups. Under this option, rewards for performance would be determined on the basis of the performance of groups of physicians. The group would be responsible for distributing the rewards, allowing for such options as investing some of the money in operational costs. There are advantages to this approach. For example, it would allow physicians to aggregate cases, addressing the issues of sample size and reward size that arise under option 1. Team-oriented care and shared accountability would also be promoted. Finally, rewarding groups could mitigate concerns about public reporting and the stigma of poor performance that arise in measuring the performance of and rewarding individual physicians. Therefore, this option may also enable more rapid implementation of a pay-for-performance program. A disadvantage of this option, however, is that holding specific providers responsible for the care of specific patients would be difficult. The distribution of rewards would be complicated, but this would be an issue for groups themselves to address. Another disadvantage of distributing rewards at the group level is that there is currently a disparity in clinical quality between care delivered by individual and small-practice physicians as compared with large physician groups (Bodenheimer et al., 2005). This method would likely increase that gap. Option 3: Combination of Options 1 and 2. This option would initially reward physician groups until measures that could reliably assess care at the individual physician level were available. Physicians would be allowed to opt to be rewarded at either level during the transition to the long-term approach of using individuals as the unit of analysis. |

(2) an advanced medical home;4 or (3) an integrated health care system. The responsible source of care would be accountable for the attribution of care delivered by the beneficiary’s various providers, as well as for the patient’s improved outcomes, safety, and efficiency. Being accountable for the patient would include being in charge of guiding the patient through the complex health care system, making referrals, checking for contraindicated medications, and having an integrated medical record with a complete medical history. The responsible source of care should be compensated for serving this function.

Recommendation 8: The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) should design the Medicare pay-for-performance program to include components that promote, recognize, and reward improved coordination of care across providers and through entire episodes of illness. Thus, CMS should (1) encourage beneficiaries and providers to identify providers who would be considered their principal responsible source of care, and (2) pay for and reward successful care coordination that meets specified standards for providers who take on that role.

|

BOX 5-3 Examples of Virtual Groups Example 1: Hospitalization-Related Virtual Group A virtual group could be defined as the hospital medical staff and physicians caring for all patients admitted for a particular condition. For example, all patients admitted to hospital A for acute myocardial infarction during a given year could be identified as the study population. All physicians who provided any care for 25 or more of these patients during the year following their index admission would be identified as part of the virtual group and eligible for inclusion in the incentive system. Quality would be assessed using the best currently available measures, including, presumably, risk-adjusted 1-year survival and adherence to the Hospital Quality Alliance and the Ambulatory care Quality Alliance technical quality measures. Resource use would be measured using price-standardized measures (e.g., relative value units, diagnosis-related groups, nursing home per diems) and would include all care received by these patients, regardless of where it was provided (including out of the area). Performance could be compared with that of similar groups or with the group’s own performance during the prior year. Rewards for improved quality and efficiency could be allocated within the virtual group based on the proportion of evaluation and management claims for services provided to the cohort. The group could also be expanded to include other cohorts (cancer, orthopedics) to increase the number of physicians involved in the reward system. Example 2: Horizontal Virtual Group Ten independent primary care physicians located in the same geographic area could agree to create a virtual group to foster a care management process for their patients with chronic conditions, which could |

It must be recognized that not all providers treating Medicare beneficiaries would be willing or able to serve this coordinating function. The Secretary of DHHS should design the particulars of how providers would be rewarded for serving this function, in addition to being eligible for rewards based on performance. The funding for this purpose need not come from the pay-for-performance reward pools discussed in Chapter 3, but could be drawn from the basic payment systems within Medicare.

Beneficiaries would have an important role in this process, in that they would work with their providers to identify a responsible source of care.

|

improve quality and value while reducing overall costs. These physicians might jointly purchase an electronic health information system, as well as discuss guidelines and the evidence base for best care practices at a monthly meeting. In joining this virtual group, the ten physicians would agree to share the costs associated with purchase and implementation of the electronic system as well as training in its use. In addition, the virtual group might agree to share the costs and administration of enhanced clinical support, such as the following:

Example 3: Virtual Groups Convened by Health Plans Health plans could play a convening role in the formation of virtual groups, for example, by providing a common information technology platform for gathering data across multiple solo or small group practices in return for a small fee. Practices would not have to be located in the same geographic area, as they would be linked by common financial and communication systems. As part of their services, plans could also track a minimum number of patients with chronic conditions and send out prompts and reminders for recommended preventive services. Reward sharing could occur through reaching of thresholds on selected performance measures (including clinical effectiveness and efficiency) for chronic conditions determined by CMS. |

Incentives, such as reductions in Medicare Part B premiums, could be used to encourage beneficiaries to make this designation. The mechanisms for this involvement should be easy for beneficiaries to understand and apply. Moreover, all activities related to this process should protect patient confidentiality and be completed in compliance with the regulations of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act.

The committee recognizes the many technical difficulties associated with implementing such a process. Nonetheless, the committee believes enhancing care coordination is essential to improving the overall quality of care and should be promoted through the use of incentives to the extent possible.

THE ROLE OF HEALTH INFORMATION TECHNOLOGIES

Potential Benefits

Information technologies might be used as a transformative tool in systems change to enhance health care delivery. For example, computerized provider order entry systems can help minimize errors in prescribing medications. Electronic health records can facilitate clinical documentation and potentially allow providers to have more complete and comprehensive information about their patients available at the point of care, and can enable improvements in the safety, effectiveness, and efficiency of treatment by making a patient’s medical records portable among multiple providers.

With respect to pay for performance, health information technologies can assist providers in data collection and reporting activities. Although the evidence is limited, use of these technologies may reduce the burden on providers and their staffs associated with reviewing medical records for reporting purposes as the number of measures grows, improve the accuracy of the data reported, and expedite the implementation of pay for performance. The sooner data are received and validated, the sooner rewards can be determined and distributed to providers. It is also true that pay for performance can encourage adoption of information technologies. If information technologies are indeed found to greatly facilitate improvement, their adoption may increase significantly. The following discussion assesses the current state of adoption, current activities, and barriers to implementation of health information technologies.

Current State of Adoption

Despite the potential importance of health information technologies, their adoption has been slow in both inpatient and ambulatory settings,

with most efforts having been initiated in the private sector. Several surveys of physician practices have found that less than one-third of physicians (12– 27 percent) use electronic health records (Anderson et al., 2005; Heffler et al., 2005; Reed and Grossman, 2006; Safran et al., 2006). Moreover, only a small proportion of the electronic health records used by ambulatory care practices possess the capabilities, including basic decision support (e.g., drug interaction alerts, notification of abnormal test results) needed to improve efficiency and quality (Heffler et al., 2005; Reed and Grossman, 2006). The extent to which electronic health records are actually designed to facilitate public reporting, however, remains unclear.

In larger, more complex health care settings, such as hospitals and health care systems, the most successful electronic health records tend to be the result of systems built in stages over many years (Chaudhry et al., 2006). Larger hospitals also tend to have higher information technology usage rates than smaller hospitals (Felt-Lisk, 2006). As of 2005, many hospitals (approximately 50 percent) had automated their major ancillary clinical systems (i.e., pharmacy, laboratory, radiology) and were incorporating those data into clinical data repositories that allow for physician access to review and retrieve results (Schoen et al., 2005). However, very few hospitals have implemented either sophisticated electronic systems capable of clinical documentation and decision support (approximately 8 percent) or computerized provider order entry that is available to any clinician (2–6 percent) (Berwick, 2002; Schoen et al., 2005). Moreover, the use of information technologies in hospitals has not yet significantly improved the quality of public reporting (Felt-Lisk, 2006).

Electronic systems should not be the same for all providers, as different providers have different needs. For example, computerized provider order entry systems in hospitals include capabilities for laboratory, radiology, and consults; none of these services are necessary for a system designed to be used in a skilled nursing facility. Adoption rates also tend to differ by provider size. According to one study, smaller providers (i.e., home health agencies, skilled nursing facilities, and groups of fewer than five physicians) can be expected to have less well-developed electronic capabilities than larger groups (i.e., hospitals and groups of 20 or more physicians), probably because of limited financial and personnel resources (Kaushal et al., 2005).

Current Activities

The federal government has initiated activities to support the development of health information technologies, as will be underscored by an executive order from the Bush Administration to require all federally financed providers to adopt uniform information technology standards and quality measurement tools (Broder, 2006). Primary among these activities is devel-

opment of a National Health Information Network (NHIN) through several efforts, including the following:

-

The Consolidated Health Informatics (CHI) initiative, which has endorsed a portfolio of existing health information interoperability standards (Bodenheimer, 2005).

-

The Healthcare Information Technology Standards Panel, a cooperative partnership of public and private stakeholders, supported and funded by the DHHS Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology with the purpose of achieving a widely accepted and useful set of standards that will enable and support widespread interoperability among health care software applications (ANSI, 2006).

-

The American Health Information Community, a commission of public and private representatives that provides input and recommendations to DHHS on the development and adoption of architecture, standards, a certification process, and a method of governance for the ongoing implementation of health information technology (Thorpe, 2005).

-

A set of 16 community health information technology grants totaling more than $22.3 million, awarded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), which are focused on data sharing and interoperability among providers, laboratories, pharmacies, and patients in several regions across the country (Cogan et al., 2005).

-

Contracts totaling $18.6 million awarded by DHHS to four consortia of technology developers and health care providers to develop prototypes for an NHIN (Dowd, 2005); and

-

Partial or full funding in support of more than 100 Regional Health Information Organizations (RHIOs)—regional collaborations throughout the country that facilitate the development, implementation, and application of secure health information systems across care settings (including those funded by AHRQ as noted above) (Ginsburg, 2005).

In addition, in the private sector, Connecting for Health has begun a National Health Information Exchange initiative, which involves three very different local health information networks—in Boston, Massachusetts; Indianapolis, Indiana; and Mendocino, California—that will work together to facilitate their secure exchange of health information (Rosenthal et al., 2005). Several RHIOs are also under way that are fully supported by private industries and/or state legislation. The federal government and other public and private stakeholders need to continue to work aggressively on the development of these mechanisms for interoperability among health information technology systems, while also ensuring the confidentiality of individual patient information.

Barriers to Implementation

The extent to which health information technologies can yield savings or better health outcomes is unclear. Gains have been proven only in large health systems and after long implementation processes. The current low level of adoption of health information technology is due to many challenges, not the least of which is cost. Electronic health record systems are an expensive and high-risk investment—one that involves not only initial acquisition and implementation costs, but also the more significant costs of short-term productivity loss, ongoing training, redesign of clinical and administrative processes, and the process of changing the way work is performed.

The issue of cost was also complicated by the existence of certain federal laws (i.e., the physician self-referral law [“Stark Law”] and the anti-kickback statute) intended to prevent payments to clinicians that might encourage overutilization of health care services. These laws, however, also created barriers to the provision of financial and other assistance by larger to smaller health care providers. On August 1, 2006, the Secretary of DHHS issued two regulations addressing these laws, lifting some of these barriers. Whether the regulations will in fact help accelerate adoption of health information technologies remains to be seen (U.S. DHHS, 2006a,b).

There is also a paucity of quantifiable data in the literature on financial returns on investment in electronic health record systems (Chaudhry et al., 2006). For ambulatory practices, the evidence is beginning to point to positive returns within 3 years, especially when the electronic health record system is integrated with a practice management system, as a result of the cost savings from reduced transcriptions and revenue gains from more appropriate coding (Lied and Sheingold, 2001; Trivedi et al., 2005; Vaccarino et al., 2005). However, electronic health record systems currently are limited in their ability to effectively recall, collate, and analyze data. Evidence regarding the possible benefits of interoperability—the ability to exchange data across providers, sites, and organizations—has been both limited and mixed. Some studies have shown significant cost savings (an annual net value of $113.9– 220.9 billion, assuming a 15-year adoption period) (Moran, 2005), while others have found none. In addition, while the federal government and others have made some progress in the promulgation of national standards for health care information exchange and interoperability—through the foundational work of the CHI initiative and the ongoing work of the Healthcare Information Technology Standards Panel, the American Health Information Community, and RHIOs—there is still a long way to go.

Another challenge faced by physician practices and hospitals has been the lack of guidance for selecting and implementing electronic health record systems; it is difficult to know whether a given system will provide the

necessary functionality in both the short and long terms and whether the vendor will remain in business to provide upgrades and ongoing technical assistance. Several efforts have been initiated to address this issue. DHHS has commissioned the Certification Commission for Healthcare Information Technology, a private, nonprofit organization, to develop and evaluate the certification criteria and inspection process for electronic health record systems. In addition, many public- and private-sector stakeholders—including CMS (through its Doctor’s Office Quality-Information Technology program), Medicare (through its Quality Improvement Organizations), professional organizations, trade associations, and industry websites—are beginning to offer technical assistance to both hospitals and physicians.

Finally, both clinicians and consumers have demonstrated resistance to the adoption of electronic health record systems to aid in systems changes. It is often thought that clinicians will need to adopt a fundamentally different way of making and documenting clinical decisions to incorporate electronic health records into their practices. The initial phase of implementation, in particular, will result in longer work hours for clinicians as they become familiar with the application and enter background information for each patient (Trivedi et al., 2005). In addition, decision supports are more useful if the input data are structured and coded, which requires that clinicians use structured input supports, such as checklists. Consumers are also resistant because of concerns about the privacy and confidentiality of their records, and physician practices and hospitals are sensitive to these concerns.

Role of Health Information Technologies in Pay for Performance

The adoption of health information technologies could facilitate data collection and reporting, and thereby expedite pay for performance. Although pay for performance might conversely accelerate adoption of information technologies, the committee does not suggest that pay for performance be contingent on providers adopting these technologies. The possession of advanced information systems can place some providers at greater advantage relative to other providers without these capabilities. The committee therefore supports all initiatives in both the public and private sectors to advance the state of health information technology, as well as all research aimed at determining whether and how significant savings associated with electronic systems can be achieved.

Recommendation 9: Because electronic health information technology will increase the probability of a successful pay-for-performance program, the Secretary of DHHS should explore a variety of approaches for assisting providers in the implementation

of electronic data collection and reporting systems to strengthen the use of consistent performance measures.

STATISTICAL ISSUES

The validity and acceptability of a system for rewarding performance depends on the quality of the data used to construct the performance measures. To ensure high-quality data, statistical reliability and validity are essential. Implementation of pay for performance also depends on the comparability of data. Appropriate adjustments must be made to the raw data to correct for clear biases and confounding elements that may be beyond the control of the provider. It is important to recognize the major role of beneficiary behavior in overall health care outcomes. These behaviors must be adjusted for and taken into account when the care delivered is being attributed to the performance of individual physicians, especially with respect to outcomes.

Deriving an accurate representation of a provider’s performance necessitates meeting minimum requirements for sample size. Sample size refers to the number of cases being used to calculate a measure. If there are not enough cases, poor or excellent outcomes may reflect sample variability rather than true performance. This issue is particularly important with respect to physicians. As noted earlier, many general practitioners may not see 25 patients—viewed as a minimum threshold for performance measures—afflicted with the same condition.

For some measures, the data may be skewed by characteristics of the patient or the environment. For example, a provider’s performance measures may look mediocre not because his skills or processes are poor, but because the cases treated are more complex than average or his patients have many comorbidities. Risk adjustment is an attempt to correct for such confounding conditions. Similar adjustments may be necessary for social, cultural, and economic differences in providers’ patients. For example, some providers may serve disproportionate numbers of nonadherent patients, patients who are economically disadvantaged and lack supplemental insurance, or those who are unable to communicate effectively with the provider. A pay-for-performance program should not penalize providers who serve such beneficiaries or create incentives to avoid them, recognizing that programs to promote better behavior should be rewarded. Such unintended adverse consequences should be compensated for and should not be neglected. These statistical issues are inherent in performance measurement, but can be adjusted for to better characterize the care that is delivered. However, much research must be completed before an optimal system is available. Methods of better accounting for sample-size problems and car-

rying out risk adjustment must be formulated to ensure the integrity of a pay-for-performance program.

SUMMARY

Implementation of a pay-for-performance program is complicated. Providers are at different levels of readiness to participate in such a program because of variations in the availability of performance measures and supporting infrastructure. Public reporting is a necessary step in rewarding performance. To help ease the burden of data collection, CMS should pay providers for reporting. It is expected that eventually, all Medicare providers will be rewarded based on their performance. Adequate financial incentives and assistance should be provided to achieve this goal. While information technologies can be useful in accelerating implementation, they are not necessary for success. A pay-for-performance program should be a learning system and should therefore undergo regular comprehensive evaluation. The next chapter addresses monitoring, evaluation, and the research agenda that must be carried out to better understand the effects of pay for performance and optimal future directions.

REFERENCES

ACP (American College of Physicians). 2006. The Advanced Medical Home: A Patient-Centered, Physician-Guided Model of Health Care. Philadephia, PA: ACP.

Anderson GF, Hussey PS, Frogner BK, Waters HR. 2005. Health spending in the United States and the rest of the industrialized world. Health Affairs 24(4):903–914.

ANSI (American National Standards Institute). 2006. Healthcare Information Technology Standards Panel. [Online]. Available: http://www.htsip.org [accessed May 30, 2006].

Baker G, Carter B. 2005. Provider Pay-for-Performance Incentive Programs: 2004 National Study Results. San Francisco, CA: Med-Vantage, Inc.

Berwick D. 2002. A user’s manual for the IOM’s “Quality Chasm” report. Health Affairs 21(3):80–90.

Bodenheimer T. 2005. The political divide in health care: A liberal perspective. Health Affairs 24(6):1426–1435.

Bodenheimer T, May JH, Berenson RA, Coughlan J. 2005. Can Money Buy Quality? Physician Response to Pay for Performance. Washington, DC: Center for Studying Health System Change.

Broder D. 2006, August 6. Administration aims to set health-care standards. Washington Post.

Chaudhry B, Wang J, Wu S, Maglione M, Mojica W, Roth E, Morton SC, Shekelle PG. 2006. Systematic review: Impact of health information technology on quality, efficiency, and costs of medical care. Annals of Internal Medicine 144(10):742–752.

CMS (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services). 2006. Hospital Compare. [Online]. Available: http://www.hospitalcompare.hhs.gov [accessed May 15, 2006].

Cogan JF, Hubbard RG, Kessler DP. 2005. Making markets work: Five steps to a better health care system. Health Affairs 24(6):1447–1457.

The Commonwealth Fund. 2006. Washington Health Policy Week in Review. [Online]. Available: http://www.cmwf.org/healthpolicyweek/healthpolicyweek_show.htm?doc_id=362624&#doc362626 [accessed June 2, 2006].

Dowd B. 2005. Coordinated agency versus autonomous consumers in health services markets. Health Affairs 24(6):1501–1511.

Felt-Lisk S. 2006. Issue Brief: New Hospital Information Technology: Is It Helping to Improve Quality? Washington, DC: Mathematica Policy Research, Inc.

Ginsburg P. 2005. Competition in health care: Its evolution over the past decade. Health Affairs 24(6):1512–1522.

Heffler S, Smith S, Keehan S, Borger C, Clemens MK, Truffer C. 2005. Trends: U.S. health spending projections for 2004–2014. Health Affairs w5.74.

Hibbard JH, Slovic P, Peters E, Finucane M. 2000. Older Consumers’ Skill in Using Comparative Data to Inform Health Plan Choice: A Preliminary Assessment. Washington, DC: Public Policy Institute, AARP.

Hibbard JH, Slovic P, Peters E, Finucane ML. 2002. Strategies for reporting health plan performance information to consumers: Evidence from controlled studies. Health Services Research 37(2):291–313.

Hibbard JH, Stockard J, Tusler M. 2005. Hospital performance reports: Impact on quality, market, share, and reputation. Health Affairs 1150–1160.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2006. Performance Measurement: Accelerating Improvement. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Jha AK, Epstein AM. 2006. The predictive accuracy of the New York state coronary artery bypass surgery report-card system. Health Affairs 25(3):844–855.

Kaushal R, Bates DW, Poon EG, Jha AK, Blumenthal D, Harvard Interfaculty Program for Health Systems Improvement NHIN Working Group. 2005. Functional gaps in attaining a national health information network. Health Affairs 24(5):1281–1289.

Kesselheim AS, Ferris TG, Studdert DM. 2006. Will physician-level measures of clinical performance be used in medical malpractice litigation? Journal of the American Medical Association 295(15):1831–1834.

Lied TR, Sheingold S. 2001. HEDIS performance trends in Medicare managed care. Health Care Financing Review 23(1):149–160.

Marshall MN, Shekelle PG, Leatherman S, Brook RH. 2000. The release of performance data: What do we expect to gain? A review of the evidence. Journal of the American Medical Association 283(14):1866–1874.

MedPAC (Medicare Payment Advisory Commission). 2005a. Report to the Congress: Medicare Payment Policy. Washington, DC: MedPAC.

MedPAC. 2005b. MedPAC Data Runs. Washington, DC: MedPAC.

MedPAC. 2006. Report to the Congress: Medicare Payment Policy. Washington, DC: MedPAC.

Moran DW. 2005. Whence and whither health insurance? A revisionist history. Health Affairs 24(6):1415–1425.

NCHS (National Center for Health Statistics). 2005. Health, United States, 2005: With Chartbook Trends in the Health of Americans. Hyattsville, MD: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Pham M. 2006. How Many Doctors Does It Take to Treat a Patient? The Challenges That Fragmented Care Poses for P4P. Unpublished.

Reed MC, Grossman JM. 2006. Data Bulletin: Growing Availability of Clinical Information Technology in Physician Practices. Washington, DC: Center for Studying Health System Change.

Robinowitz DL, Dudley RA. 2006. Public reporting of provider performance: Can its impact be made greater? Annual Review of Public Health 27:517–536.

Rosenthal MB, Frank RG, Li Z, Epstein AM. 2005. Early experience with pay-for-performance: From concept to practice. Journal of the American Medical Association 294(14): 1788–1793.

Safran DG, Miller W, Beckman H. 2006. Organizational dimensions of relationship-centered care: Theory, evidence, and practice. Journal of General Internal Medicine 21(s1): S9–S15.

Schoen C, Osborn R, Huynh PT, Doty M, Zapert K, Peugh J, Davis K. 2005. Taking the pulse of health care systems: Experiences of patients with health problems in six countries. Health Affairs w5.509.

Thorpe KE. 2005. The rise in health care spending and what to do about it. Health Affairs 24(6):1436–1445.

Trivedi AN, Zaslavsky AM, Schneider EC, Ayanian JZ. 2005. Trends in the quality of care and racial disparities in Medicare managed care. New England Journal of Medicine 353(7):692–700.

U.S. DHHS (United States Department of Health and Human Services). 2006a. Medicare and state health care programs: Fraud and abuse; safe harbors for certain electronic prescribing and electronic health records arrangements under the anti-kickback statute; final rule. Federal Register 71(152):45109–45137.

U.S. DHHS. 2006b. Medicare program; physicians referrals to health care entities with which they have financial relationships; exceptions for certain electronic prescribing and electronic health records arrangements. Federal Register 71(152):45139–45171.

U.S. GAO (United States General Accounting Office). 2003. Physician Workforce: Physician Supply Increased in Metropolitan and Nonmetropolitan Areas but Geographic Disparities Persisted. [Online]. Available: http://www.gao.gov/new.items/d04124.pdf [accessed January 12, 2006].

USPSTF (U.S. Preventive Services Task Force). 2006. Guide to Clinical Preventive Services. [Online]. Available: http://www.ahrq.gov/clinic/cps.3dix.htm [accessed June 13, 2006].

Vaccarino V, Rathore SS, Wenger NK, Frederick PD, Abramson JL, Barron HV, Manhapra A, Mallik S, Krumholz HM, National Registry of Myocardial Infarction Investigators. 2005. Sex and racial differences in the management of acute myocardial infarction, 1994 through 2002. New England Journal of Medicine 353(7):671–682.

Vaiana ME, McGlynn EA. 2002. What cognitive science tells us about the design of reports for consumers. Medical Care Research and Review 59(1):35–59.

Werner RM, Asch DA. 2005. The unintended consequences of publicly reporting quality information. Journal of the American Medical Association 293(10):1239–1244.