8

Using Tax Return Data to Improve Estimates of Corporate Profits

George A. Plesko

University of Connecticut School of Business

This chapter describes the role of tax and financial accounting information in the estimation of corporate profits, summarizes the current dual-reporting requirement that publicly traded firms are subject to, and describes how a broader use of tax return information, coupled with a greater use of financial accounting information, might increase the accuracy of preliminary national income estimates of corporate profits.

MEASURING CORPORATE INCOME

For the purposes of this volume, there are two relevant measures available to assess the profitability of corporations. The first, based on the rules for financial reporting (generally referred to as “book income”), provides a measure of income to the users of financial statement information. The users, under the concepts of financial accounting for publicly traded corporations, are investors, creditors, and any other party needing information to make a decision about whether or not to engage in a business relationship with a firm, but not necessarily able to compel the firm to provide the information.

It is worth noting that foundations of financial accounting and reporting do not explicitly include tax authorities as a user. The reason for this exclusion is that financial accounting disclosures are intended to provide information to those who do not otherwise have the ability to demand information. The separation of audiences, and rules, leads to the second measure of corporate income, based on the Internal Revenue Code. In contrast to the rules of financial reporting, tax reporting removes

much of the discretion for the application of rules that are built into financial reporting.

The differences between the amount of income reported to shareholders and the amounts reported to tax authorities, known as book-tax differences, have generated attention both in the press and in policy. However, once a dual measurement system is in place, income differences are a natural occurrence, and the key issue becomes understanding the causes and consequences of the differences. Book-tax differences have been a characteristic of the U.S. reporting system since the inception of the corporate income tax, generating academic interest from the start. For example, Smith and Butters (1949) provide an analysis of book-tax differences for a small sample of corporations active during the 1930s.

SOURCES OF BOOK-TAX DIFFERENCES

Book-tax differences occur because the amount of income reported as earned is based on different concepts and rules under each reporting system. Since the target audience of financial statements is investors and others who need information to make decisions about a company, including whether to invest in the company’s equity or debt, companies that issue publicly traded equity or debt securities are required by the Securities and Exchange Commission to file audited financial statements. Such statements must follow generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP), which include an adherence to pronouncements of the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) and other accounting standards.

Tax accounting is designed to administer the U.S. tax laws, with the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) the primary audience for tax filings. In contrast to GAAP, tax rules can change frequently, depending on legislative initiatives, and are not necessarily designed to present as consistent a definition of income over time as are financial accounting rules.

An important element of financial accounting is the amount of discretion left to the corporation in implementing GAAP in their business. For example, in determining the useful life and depreciation pattern of a capital asset, depreciation schedules of the same asset can vary by company and by usage and usually follow a straight-line pattern. Tax depreciation is determined by the Internal Revenue Code and leaves less discretion to the company. The lack of discretion in the tax code is intended to lead to more uniform application of the tax system.

Differences between tax and financial measures of income can arise from two types of measurement differences in the accounting systems: temporary and permanent. Temporary (timing) differences occur when both tax and financial reporting recognize the same total amount of income or expense, but they do so either over different time periods or in

different patterns over the same period. Timing differences arise not only from the different reporting rules under each system, but also because GAAP allows managers greater discretion in determining the amounts of income and expense in each period than does the tax system.

Permanent differences in the measures of income arise when a particular item of income or expense is recognized under one system but not the other. For example, tax-exempt interest on municipal bonds is included in book income but not in the determination of tax net income.

Both temporary and permanent differences are reported in corpora-tions’ financial statements. Under FASB’s Statement of Financial Accounting Standards Number 109, corporations report a total amount of tax liability based on current-year financial reporting income, delineating the portion currently owed to the government from that which is deferred due to differences in income and expense recognition between the two methods. If the deferred portion is positive, a deferred tax liability is created, representing the amount of taxes not paid on financial statement income during this period because of temporary differences reducing taxable income below book income. Such is usually the case in the short term with depreciation, as more deductions are taken for tax purposes during the early years of an asset’s life than are recognized as expenses for book purposes. The deferred tax liability associated with the asset on a corporation’s financial statements represent the (undiscounted) amount of tax to be paid in the future relative to future book earnings when the tax depreciation deductions fall below the book depreciation expense. In contrast to deferred tax liabilities, deferred tax assets are created when more taxes are paid than would be paid if financial reporting income were used to base tax liability, and they represent a financial claim on the government for taxes paid ahead of time relative to financial reporting.

Permanent differences, such as the effect of tax-exempt interest, never reverse and therefore do not create deferred tax assets or liabilities. Corporations account for permanent differences in a separate financial disclosure in the tax footnote of their financial statements.

Book-tax differences have generated increased attention since the 1999 Treasury Department report on tax shelters and related testimony (Talisman, 2000), in which reporting differences were suggested as evidence of increased tax sheltering by corporations. The Joint Committee on Taxation (2003) report on Enron provided additional evidence of tax sheltering behavior and of reporting differences for book and tax purposes.

BEA METHODOLOGY

The methodology used by the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) explicitly incorporates a combination of publicly available information

drawn from both financial statements and tax return data to estimate corporate income. The concept of corporate income in the national accounts is closer to tax than book income, but the time lag in the availability of tax data, described below, requires BEA to forecast current income based on past tax data and recent financial reports. The recent attention to the role of book-tax differences in affecting the estimate of corporate profits is related to the occurrence of large, unexpected differences in the growth rate of each income measure in the 1990s and early 2000s. The sharp revisions in estimated corporate profits have been discussed by others, including the Congressional Budget Office (2005), Mead et al. (2004), and Patrick (2001).

The rules governing financial reporting by public corporations, specifically Financial Accounting Standard 109 called “Accounting for Income Taxes” (Financial Accounting Standard Board, 1992), require firms to reconcile their book measure of tax liability to their actual liability. Furthermore, income tax reporting requires firms to reconcile their taxable income to their book income on Form 1120. As a result, the underlying economic activity of a firm is reported using two distinct measurement systems and, in theory, allows for a better understanding of the financial position of a firm.

Ideally, the information in the tax and financial statements is complementary, since each provides a unique measure of the same economic activities. Furthermore, research suggests that information about book-tax differences, as reported in firms’ tax footnote, is useful to investors (Hanlon et al., 2005) in predicting their future performance.

However, a problem occurs when the components of the tax disclosure are examined at the firm level and a user tries to determine specific information, such as taxable income and a company’s tax payments. Financial disclosures have been found to be unsatisfactory in providing inferences about the tax attributes of a firm (see Hanlon, 2003; Plesko, 2000a, 2003).

Figure 8-1 is a schematic of these reporting relations. Until 2004, the reconciliation of income for tax reporting purposes was reported on the Schedule M-1 of the corporate income tax return Form 1120. An analysis of the M-1’s shortcomings outlined by Mills and Plesko (2003) shows that these reconciliations were of little practical value to the IRS. As a result, for tax year 2004 and after, the Schedule M-1 has been replaced by Schedule M-3 for larger corporations. The efficacy of the Schedule M-3 has yet to be assessed.

The importance of these issues, from an empirical view, is that the financial statement information that BEA relies on will misrepresent the taxable income numbers it is trying to infer if book-tax differences are large and changing in ways not observable in the financial data. Recent

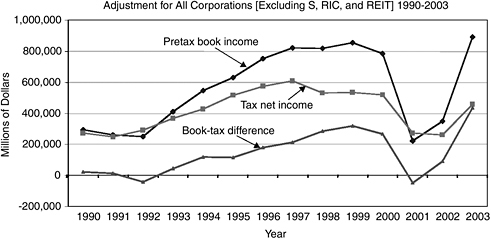

FIGURE 8-1 Pretax book income, tax net income, book-tax difference, M-1 explains, and estimated intercompany dividend.

work by Plesko (2000b, 2002), Plesko and Shumofsky (2005), and Boynton et al. (2005) has established that book-tax differences are not only large, but also growing. Figure 8-2, reproduced from Boynton et al. (2005), shows that book income has differed from taxable income both in scale and in annual changes. Similarly, Table 8-1 shows that these differences are not uniform across industries.

FIGURE 8-2 The book-tax difference as a percentage of tax net income, 1990-2003.

TABLE 8-1 How Significant Are Book-Tax Differences?

|

|

BTD as a Share of Tax Net Income |

|||

|

Active Corporations |

All Industrial Divisions |

Raw Materials and Energy Production |

Goods Production |

Distribution and Transportation of Goods |

|

1995 |

0.104 |

|

|

|

|

1996 |

0.140 |

|

|

|

|

1997 |

0.182 |

|

|

|

|

1998 |

0.242 |

–0.088 |

0.037 |

0.116 |

|

1999 |

0.690 |

0.297 |

0.603 |

0.471 |

|

2000 |

0.611 |

0.900 |

0.406 |

0.273 |

|

2001 |

–0.150 |

1.277 |

–0.026 |

0.103 |

As Figure 8-2 shows, there are two years in which the book-tax difference is negative, 1992 and 2001, and both are generally explainable. In 1992, a financial accounting change required firms to begin recognition of expenses to pay postretirement benefits, leading to large reductions in reported book income for that year. The negative difference in 2001 is driven by firms with large negative tax net income that have smaller, or positive, book income. The change in 2003, the most recent year for which data are available, is dramatic, with book income almost double taxable income.

The existence, magnitude, and pattern of book-tax differences raises two important issues for national income purposes: (1) why these differences exist and (2) whether these differences can be identified in financial statements in the years before tax return data become available and corporate profits estimates are finalized. Since both sets of information are driven by the same underlying economic events, the hope is that financial information, which is available sooner than tax information, can complement other available data to make profit estimates and generate both time-lier, and more accurate, estimates.

THE TIMING OF INCOME REPORTING

In the case of corporate profits, it is important to note that the amount of information released to investors a short time after the accounting period has ended is large relative to that which can be inferred concurrently

|

Information |

Finance, Insurance, Real Estate, and Rental and Leasing |

Professional and Business Services |

Education, Health, and Social Assistance |

Leisure, Accommodation, and Food Services |

Other Services |

|

0.954 |

0.945 |

0.064 |

7.726 |

0.323 |

–0.138 |

|

1.021 |

1.356 |

0.647 |

7.349 |

0.097 |

–0.530 |

|

4.830 |

1.062 |

0.931 |

3.286 |

0.283 |

–0.503 |

|

2.784 |

0.181 |

0.272 |

1.973 |

0.393 |

3.047 |

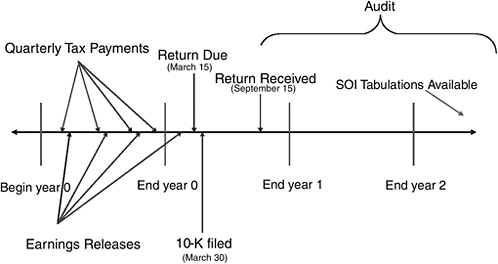

FIGURE 8-3 Timeline of financial and tax reporting.

from the tax system. Figure 8-3 provides an abbreviated time line for a calendar year corporation, that is, one with a year end of December 31.

Companies make quarterly announcements of their profits and quarterly payments of their expected tax liabilities, although these dates do not directly align. Of greatest importance is when annual earnings, which

are described here and in Figure 8-3 as year 0, ending on December 31, are disclosed. For publicly traded firms, financial reports are filed by March 30 of the following year. The due date for a calendar year corporation to file a tax return is March 15, prior to the filing of financial statements; however, corporations typically file their returns, after an extension, six months later. As a result, the tax return is not usually filed until September 15.

Shortly after the March 30 filing date, financial data become available in machine-readable form. Tax return data, however, may take two or more years to collect and tabulate and exclude any audit activities. If corporate financial reporting can be used to infer tax attributes, it may be possible to effectively model and estimate taxable income two or more years ahead of having tax return data. Quarterly tax liability patterns are potentially inferable via estimated tax payments; the financial statements, in theory, provide sufficient disclosure of tax items to estimate the taxable income of the firm. In other words, if the financial statement information correctly conveys the information it is intended to, it can be used to predict, or improve the predictions of, the ultimate aggregate tax information eventually reported in the Statistics of Income tabulations.

SOURCES OF DIFFERENCES

Identifying the sources and magnitude of the differences between book income and taxable income has been a growing research interest since the 1999 Treasury Department study. The previous discussion suggests that the differences between book and taxable income are relatively straightforward and dictated by a clear set of regulatory requirements. In practice, however, understanding these differences is not a simple matter. Two different approaches have been used to analyze them, depending on the data available. The first approach uses publicly available data to estimate the book-tax difference using information in financial statements and then attempts to model the amount of book-tax difference as a function of firm and industry characteristics (such as the amount of depreciable assets or foreign operations). The second, direct, approach for analyzing book-tax differences relies on tabulations from tax returns and is discussed by Plesko (2002), Plesko and Shumofsky (2005), and Boynton et al. (2005).

A significant factor in the recent divergence between book and taxable income has been stock options, which do not affect financial accounting earnings but do reduce taxable income. The difficulty in isolating their effect, however, is that, for tax purposes, the option-related expense is included in total compensation and not separately identified. Thus, even

with access to tax return data, disclosures may be insufficient to fully understand the causes of the differences.

The new Schedule M-3 (see http://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-utl/2005f1120sm3.pdf) will provide a large amount of additional data to help the IRS, Treasury, and BEA better understand how financial reporting can inform tax administration. Schedule M-3 covers three pages and provides much more information than the Schedule M-1, which consisted of 10 lines.

An important element of the M-3 appears on page 1, where firms are now required to provide identifying information on the financial statement filing entity of which the tax entity is a part. This is followed by a precise derivation of the amount of book income attributable to the tax entity. This reconciliation will better enable tax authorities and analysts to adjust for consolidation differences.

The remaining two pages of the M-3 provide greater detail relative to what was provided prior to 2004, requiring information not only on the amount of an item reported for financial and tax accounting purposes, but also a delineation of the amount of the difference that is temporary and permanent. Among the additional items now reported, stock options appear in Part III on Line 8.

THE BENEFITS OF ADDITIONAL DATA

Two brief examples demonstrate the importance of additional data to analysts. First, in forecasting corporate profits, the additional data provided by the M-3 will offer greater insight into the relation between taxable income and the book profits reported in financial statements. This greater detail should allow for a better use of book income and other information in financial statements to estimate the pattern that taxable income will follow.

Tax policy will also be assisted by the collection of additional information. With the Schedule M-3, not only will analysts have more data concerning the specific operations and organization of a firm, including specific decisions related to tax planning, but also the link to financial statements will make contemporaneous financial information more useful. In estimating the effects of changes in tax policy on businesses, better information about current operations, rather than that reported for previous tax years, should allow for improved estimates of the economic and fiscal effects of proposed changes.

The tax return is the ultimate source of information for determining the effects of tax policy, but it is not the only one. There is substantial evidence suggesting that firms look beyond tax reporting when making tax planning decisions. Changes in corporate behavior, such as invest-

ment or financial policy, take place in a tax system that interacts with the capital market through other types of reporting. Without a way to link all of the constraints affecting a business, analysts will have difficulty fully identifying and accurately measuring the effects of changes in tax policy. A better use of both financial and tax information, supplemented by new data provided by the new Schedule M-3, will provide a better understanding of the interrelationships between the two systems.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I have benefited from discussions with Dan Feenberg, Ralph Rector, John Phillips, and David Weber.

REFERENCES

Boynton, C., P. DeFilippes, and E. Legel 2005 Prelude to schedule M-3: Schedule M-1 corporate book-tax difference data 1990-2003. 109 Tax Notes 1579 (December 19).

Congressional Budget Office 2005 The Budget and Economic Outlook: An Update. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Financial Accounting Standards Board 1992 Accounting for Income Taxes. FASB Statement No. 109. Norwalk, CT: Financial Accounting Standards Board.

Hanlon, M. 2003 What can we infer about a firm’s taxable income from its financial statements? National Tax Journal (4):831-863.

Hanlon, M., S. Kelley LaPlante, and T. Shevlin 2005 Evidence on the Possible Information Loss of Conforming Book Income and Taxable Income. Available: http://ssrn.com/abstract=686402 or DOI: 10.2139/ssrn.686402 [accessed May 2006].

Joint Committee on Taxation 2003 Report of Investigation of Enron Corporation and Related Entities Regarding Federal Tax and Compensation Issues, and Policy Recommendations. (JCS-3-03). Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. Available: http://www.gpo.gov/congress/joint/jcs-3-03/vol1/index.html [accessed May 2006].

Manzon, G., and G. Plesko 2002 The relation between financial and tax reporting measures of income. Tax Law Review 55(2):175-214.

Mead, C.I., B.R. Moulton, and K. Patrick 2004 NIPA Corporate Profits and Reported Earnings: A Comparison and Measurement Issues. Paper presented at the ASSA/AEA meetings, January 3-5, San Diego, CA. Available: http://www.bea.gov/bea/papers.htm [accessed May 2006].

Mills, L.F., and G.A. Plesko 2003 Bridging the reporting gap: A proposal for more informative reconciling of book and tax income. National Tax Journal (4):865-893.

Patrick, K. 2001 Comparing NIPA profits with S&P 500 profits. Survey of Current Business (April):16-20.

Plesko, G.A. 2000a Book-tax differences and the measurement of corporate income. Proceedings of the Ninety-second Annual Conference on Taxation 1999:171-176.

2000b Evidence and theory on corporate tax shelters. Proceedings of the Ninety-second Annual Conference on Taxation 1999:367-371.

2002 Reconciling corporation book and tax net income, tax years 1996-1998. SOI Bulletin 21(4):1-16.

2003 An evaluation of alternative measures of corporate tax rates. Journal of Accounting and Economics 35(2):201-226.

Plesko, G.A., and N. Shumofsky 2005 Reconciling Corporations’ Book and Taxable Income, 1995–2001. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Smith, D.T., and Butters, J.K . 1949 Taxable and Business Income. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Talisman, J. 2000 Penalty and Interest Provisions, Corporate Tax Shelters. U.S. Department of the Treasury Testimony before the Senate Committee on Finance, March 8.

U.S. Department of the Treasury 1999 The Problem of Corporate Tax Shelters: Discussion, Analysis and Legislative Proposals. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.