1

Introduction

Aviation Safety Responsibilities of the Federal Aviation Administration

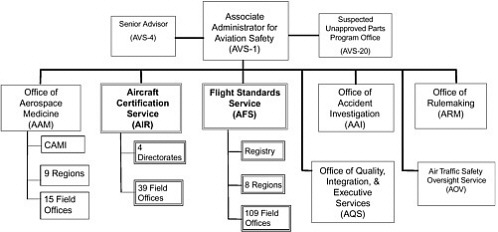

A primary mission of the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) is the assurance of safety in civil aviation, both private and commercial. To accomplish this mission, the FAA has promulgated a large number of regulations and has established a major division, the Office of Aviation Safety, to enforce and maintain the regulations and effectively promote safety in aviation. Within the office there are several subordinate organizations (see Figure 1-1). This study is concerned with two of them (highlighted in the figure): the Flight Standards Service (called AFS), charged with overseeing aviation operations and maintenance, as well as other programs, and the Aircraft Certification Service (AIR), charged with ensuring the safety of aircraft through regulation and oversight of their design and manufacture.

The present study was commissioned to examine the models and methods that have been used to determine the staffing needs for aviation safety inspectors for these two units, who are responsible for ensuring the safety of nearly all critical functions of the aviation industry. Currently there are between 3,000 and 4,000 FAA inspectors in these two organizations, as well as a large number of what are called designees, who are

nongovernment personnel authorized by the FAA to perform some inspection functions.1

Aviation Safety Inspectors

The AFS employs more than 3,400 personnel in the aviation safety inspector (ASI) job series 1825. These are the people who work with the aviation community to promote safety and enforce FAA regulations. These inspectors include specialists in operations, maintenance, and avionics, and some of them are also responsible for oversight of cabin safety and dispatch functions.

Their duties are extremely diverse, as are the sectors of the aviation industry they oversee. For example, one operations inspector may be responsible for a number of air taxi services, agricultural applicators (crop dusters), and flying schools, while another may have responsibility for a portion of the operations of a major airline. One maintenance inspector may have primary responsibility for a very large airline overhaul facility, while another may be tasked with overseeing a number of small repair stations. Many of the AFS inspectors are also responsible for oversight of designees, the non-FAA inspectors to whom inspection and approval authority may be delegated. The use of designees is intended to expand the capability of the inspection system without increasing the number of FAA inspectors or increasing their workload, but it imposes a workload of its own on those tasked with monitoring the designees.

The AIR has fewer than 175 series 1825 inspectors, but their responsibility is great. In cooperation with the greater number of aviation safety engineers employed by AIR, they must ensure the safety and compliance of aircraft design and manufacturing, from the smallest safety-related components to entire airplanes. AIR personnel are supplemented by a large number of designees, who may be employed by manufacturers of aircraft or aircraft components or may be self-employed.

Roles and Duties

The traditional role of the ASI is to be the frontline FAA regulatory contact with the aviation industry. The industry includes aircraft operators (e.g., air carriers of all sizes, air taxi services, general aviation opera

tors, agricultural applicators), pilots, flight attendants, dispatchers, flight and maintenance schools, maintenance facilities and their personnel, aircraft and component manufacturers, and other aviation-related facilities and personnel. ASIs historically have been both enforcers, seeing that the aviation industry complies with all Federal Aviation Regulations (FARs), and advisers, helping the firms for which they are responsible to operate safely and efficiently. Their work thus involves more than policing the industry. ASIs are expected to work with their aviation customers to inform them of new requirements and help them interpret and comply with the regulations, to troubleshoot problems that involve compliance with the regulations, and to educate industry personnel in safe practices and procedures.

Until recently, the typical ASI spent much of his or her time in handson inspection duties, observing and assessing the performance of the people and aviation businesses for which he or she was responsible and ensuring that they met the requirements of the FARs. ASIs have been expected to have experience in and technical knowledge of the aviation industry as qualifications for employment, and most AFS inspectors are required to have certification and experience as mechanics or pilots at the time of hiring (U.S. Office of Personnel Management, 1999).

Stresses imposed by the sustained growth in both the sheer volume of air travel and the complexity of the industry’s operations have forced significant changes on the inspection system, including these traditional ASI roles. The FAA is working in a number of areas to maintain safety and performance in the face of growing demands. Among the changes confronting the agency are new technologies in airframes, propulsion systems, and avionics; altered manufacturing and maintenance operations and management systems; and revamped airline operations and business models. Specific examples include the emergence of low-cost airlines and the increased outsourcing of aircraft maintenance tasks to subcontractors, many of them outside the United States. In response to such changes, the FAA is moving to a “system safety” approach to oversight, with less emphasis on direct physical contact with individual equipment and operators and greater emphasis on the oversight of programs and processes to ensure safety. Box 1-1 presents a capsule description of system safety from the FAA’s System Safety Handbook (Federal Aviation Administration, 2000b).

Many of the data on which the system safety approach rests now come from automated data capture systems maintained by the aviation industry. They are collected in database systems designed to help FAA inspectors detect and flag trends that might indicate incipient safety problems. One prominent example is the Air Transportation Oversight System (described in Chapter 4) now being phased into use for monitoring

|

BOX 1-1 FAA System Safety Definition The application of engineering and management principles, criteria, and techniques to optimize safety within the constraints of operational effectiveness, time, and cost throughout all phases of the system life cycle. A standardized management and engineering discipline that integrates the consideration of man, machine, and environment in planning, designing, testing, operating, and maintaining FAA operations, procedures, and acquisition projects. System safety is applied throughout a system’s entire life cycle to achieve an acceptable level of risk within the constraints of operational effectiveness, time, and cost. SOURCE: Federal Aviation Administration (2000b, p. A-15). |

of major airlines. To use this and other system safety tools effectively, the FAA must have ASIs who are sophisticated database users, with knowledge of system safety principles and processes and an analytic approach to their work. This is a different skill set from the one that supports on-site inspection. Other FAA initiatives, like Flight Operational Quality Assurance (Federal Aviation Administration, 2001) and the Aviation Safety Action Program (Federal Aviation Administration, 2002a) have similar skill requirements. The increasing emphasis on the use of system safety methods also means that many ASIs will interface less with frontline operational personnel in the aviation industry and more with technical professionals and managers, and they will need to understand the jobs of those personnel. They also will have increasing responsibility for interpreting the regulations and working cooperatively with aviation industry personnel.

Origin of the Study

The number of ASIs employed by the FAA has remained nearly unchanged over the past several years, while aviation industries, especially the commercial air carriers, have been expanding and changing rapidly. Increasingly, the FAA has used designees to assume some of the responsibilities formerly assigned to ASIs. There is concern in several communities, including the labor union that represents many of the ASIs, Professional Airways Systems Specialists (PASS), that the ASI staffing levels may not be adequate to the tasks the inspectors face. The Aviation Subcommittee of the U.S. House of Representatives’ Committee on Transpor-

tation and Infrastructure responded to these concerns by including the current study in the Vision 100—Century of Aviation Reauthorization Act of 2003. The aviation subcommittee and others have some specific concerns:

-

The overall ASI staffing level may be too low for the current and expected near-term workload, and it may preclude effective responses to peak or quick-response requirements.

-

The FAA may be relying excessively on designees to perform work that should be done by FAA employees.

-

Designees may be subject to pressures and incentives that could affect the integrity of their work performance.

-

The workload involved in the oversight of designees may be greater than is recognized in the staffing models now in use.

-

-

The FAA’s ability to monitor outsourced work, especially maintenance, may be insufficient for emerging requirements.

-

The distribution of ASI staff across FAA regions, districts, and facilities may not be consistent with the distribution of the workload, especially in the face of the aforementioned growth in volume and complexity.

-

Some offices may experience work overload while others are slack, resulting in wide variation in workload across the inspector workforce.

-

The FAA may not have geographically redistributed its inspector resources in response to industry changes.

-

The Congress requested the U.S. Government Accountability Office to address the use and management of designees (see GAO 05-40, October 2004) as well as issues associated with ASI training (see GAO 05-728, September 2005), and asked the National Academies to address only ASI staffing issues.

The Committee’s Task

The objective of the study is to determine the strengths and weaknesses of the methods and models that the FAA now uses in developing staffing standards and projections of staffing needs for ASIs and to advise the FAA on potential improvements. The term “staffing standards,” as used by the Aviation Safety organizatoin (AVS) for manpower planning, does not imply any measure of skill level or qualitative differences in knowledge, skills, or abilities beyond those implied by published qualifications for hiring or promotion as a particular type of inspector at a particular level.

This distinction is important for present purposes, in that it represents a long-standing functional division that persists in the professional human resources and staffing community. Determining and providing the number of personnel in various categories that an organization needs to accomplish its goals (the current AVS focus) is a manpower planning and management function, whereas describing and classifying jobs and establishing the knowledge, skills, abilities (KSA) requirements for each are considered human resource or personnel management functions. To maintain this distinction, we have used the word “staffing” to refer only to manpower issues and functions throughout this report.

Although the committee’s formal charge is focused explicitly on manpower planning and management functions, it was clear from the outset that any improvement in the FAA’s approach to staffing would need to begin by addressing human resource and personnel management deficiencies—notably the accuracy and currency of job descriptions and KSA requirements, along with the establishment of sound performance measures. Although expertise in these functional areas was well represented on the committee, actually addressing such deficiencies (i.e., by identifying the extent and nature of specific shortcomings) was clearly well beyond the scope of this limited study. Consequently, attention was directed primarily toward the FAA’s staffing systems and models, along with comparative manpower and staffing practices from other organizations, under the assumption that any changes would be preceded by investment in the human resource prerequisites.

The formal task statement from the FAA’s contract with the National Research Council (NRC) reads:

-

Critically examine the current staffing standards for FAA Aviation Safety Inspectors and the assumptions underlying those standards. The committee will confine its study to ASIs only; other inspector jobs will not be considered. The committee will not consider issues of compensation, work rules, or similar labor relations matters.

-

Gather information about the ASI job series and about the specific factors that may characterize the FAA as an organization and the ASI job series that would influence the choice of methods that might best be used to develop staffing standards; for example, it will compare engineered to performance-based staffing standards.

-

Review the staffing models, methodologies, and tools currently available, and some of those in use at other organizations with important similarities to the FAA, and determine which might be applicable or adaptable to the FAA’s needs.

-

Propose models, methods, and tools that would enable the FAA to more accurately estimate ASI staffing needs and allocate staffing resourc-

-

es at the national, regional, and facility levels, particularly in light of the occasional but urgent need to reallocate resources on short notice.

-

Estimate the approximate cost and length of time needed to develop the appropriate models.

From the task statement, it should be clear that the committee’s task, rather than directly addressing the stakeholders’ concerns outlined earlier, was to help the FAA identify and implement methods and models to support sound staffing decisions responsive to those concerns.

The National Academies’ Response

The Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education of the NRC, an operating arm of the National Academies, entered into a contract with the FAA in June 2004 to perform the present study. A committee of nine experts was appointed to perform the study, following the procedures mandated for all NRC committee appointments. These procedures are designed to ensure that committee members are chosen for their expertise, independence, and diversity and that the committee’s membership is balanced and without conflicts of interest. The appointments were finalized after the discussion of sources of potential bias and conflict of interest at the committee’s first meeting in January 2005. Brief biographies of the committee members appear in Appendix C.

The Committee’s Approach

We developed our approach to the task at the first meeting. The committee identified information needs in several domains, including the FAA and its safety inspector staffing history, methodologies, constraints, and requirements; the technical and scholarly literature on manpower and staffing methodology; the experience of other organizations in their approach to manpower and staffing; and the perceptions of individuals and organizations that have a stake in ASI staffing. We developed plans for obtaining and analyzing the needed information and for organizing the report. The committee also discussed the scope of its task and determined what would and would not be attempted.

Defining the Project Scope

The committee’s charge was to examine the manpower planning methods and models currently used by the FAA for establishing ASI staffing standards or levels and to suggest approaches aimed at improvement. We were not tasked to develop an ASI staffing model for the FAA

nor to implement such a model to determine how many ASIs are needed. We have been careful to explain this to the FAA and to all stakeholders.

This report therefore reviews the information we were able to obtain, evaluates alternatives, and provides the FAA with recommendations for approaching the core questions in an effort to develop and implement improved ASI staffing standards. While any such effort does involve modeling, and the committee devoted considerable attention to this facet of our charge, it is important to recognize that the utility of any manpower modeling approach rests heavily on situational characteristics and ultimate objectives. Thus considerable attention is paid in this report to the fundamental properties and requirements of models as they relate to the specific resources and objectives of the FAA’s ASI program. It is important to remember also that models are used as tools in a broader context of manpower planning and resource management and are not the sole determinant in staffing decisions. The current staffing model reflects many, but not all, of the factors that drive the need for ASI staff, and the decision process must take these other factors into consideration.

A point that bears repeating is that although the committee’s major task was to study manpower questions, we considered that it was unlikely that a change in manpower planning methods would be profitable until other human resource management issues were addressed, and we have devoted Chapter 4 to a discussion of these issues.

Data Gathering

The committee gathered information from the FAA and stakeholders on several issues, including:

-

the current staffing situation in the AFS and AIR organizations;

-

the history of staffing standards and methods in these organizations;

-

the FAA’s hopes and expectations for any new staffing methodology or model;

-

the environmental factors that drive staffing needs and resources;

-

the perceptions of ASIs and managers and of stakeholders in ASI staffing, including various sectors of the aviation industry; and

-

the FAA regulations and guidance that control and influence ASI staffing.

We used several methods to gather the information needed. These are described in detail below.

Literature Review. The committee and its staff searched for and reviewed a large number of FAA documents relevant to the work of ASIs and ASI

staffing (see the Bibliography). Most of the committee members have expertise in manpower, staffing, and workload assessment, and they were able to draw on their professional experience when reviewing and evaluating these materials. The materials we reviewed include:

-

Documents describing the FAA organizations in which the aviation safety inspectors work. These included organizational handbooks, web pages, and other materials.

-

Documents describing the jobs and job qualifications of ASIs. These included job postings and descriptions, job classification guidance, and qualification standards.

-

Specific regulations enforced by ASIs and documents describing the general regulatory environment in which ASIs work, including major FAA programs that ASIs are charged with implementing. These included parts of the FARs and documents describing and providing implementation guidance for such programs as the Air Transportation Oversight System, the Aircraft Certification Systems Evaluation Program, Flight Operational Quality Assurance, the Commercial Aviation Safety Team, and others.

-

Orders, guides, and handbooks providing work instructions and requirements for ASIs. These included FAA Orders in the 8300 series (Federal Aviation Administration, 2004a), the 8400 series (Federal Aviation Administration, 1994, 2004c, 2005b, 2005c, undated), and the 8700 series (Federal Aviation Administration, 2003b, 2004b), which are handbooks for various inspection programs; the National Flight Standards Work Program Guidelines (Federal Aviation Administration, 2005a), the guidance for the management of designees (Federal Aviation Administration, 2003a), as well as others.

-

Documents setting forth federal government and FAA personnel and staffing policies and procedures, including past and present staffing standards and descriptions of FAA labor reporting systems. These included descriptions and documentation provided by FAA headquarters staff for the Holistic Staffing Model, the Automated Staffing Allocation Model, and the staffing system for AIR (Order 1380.49 series and related documents) (Federal Aviation Administration, 1989, 1995, 1997, 1999, 2002b), as well as others.

We examined many other FAA documents and web pages with possible relevance to the committee’s task. FAA staff provided helpful explanations and answered the committee’s questions about the documents and their applicability to ASIs today. For some orders and guidance documents, the committee was unable to obtain definitive information on how

they were being applied or whether they were currently in force. These were related mainly to the labor recording systems used to record ASI activities, tasks, and work production, especially in AIR. These systems, documenting tasks, workloads, and the time to complete standard units of work, provide critical input required to implement staffing models.

The committee also reviewed a number of reports of the U.S. Government Accountability Office and the U.S. Department of Transportation Inspector General’s Office that have relevance to ASI staffing. Committee staff met with GAO personnel who performed their studies of designee management and ASI training to gain a better understanding of those studies, which were in progress as our work began. In addition to all of these materials, some of the stakeholders and other sources provided documents for our review. Some of these were clearly opinion pieces advocating specific points of view or courses of action and were evaluated as such.

The committee reviewed a selection of scientific and professional literature in several areas of human resources: manpower allocation and modeling, staffing, workload measurement, and the like. We were especially interested in materials describing alternative approaches to manpower and staffing used by organizations similar to the FAA in important ways, as well as articles on principles and methods used to establish staffing models and systems.

A subgroup of the committee with special expertise in manpower and staffing models was tasked to explore alternative modeling approaches for their potential relevance to the FAA staffing situation. This group reviewed approaches used by the U.S. military and other government and civilian organizations, as well as those used or previously considered for use by the FAA. The organizations studied include the U.S. Army, the U.S. Air Force, the Environmental Protection Agency, and others.

Briefings by FAA Headquarters Staff. We invited FAA headquarters personnel from AFS and AIR to brief us at our first committee meeting and later requested additional briefings on specific aspects of ASI staffing. The FAA headquarters personnel who briefed the committee or responded to questions are listed in Table 1-1. Some FAA personnel attended the stakeholder panels described below, providing clarification or additional information there as well as in formal briefings. In addition, the meetings of the committee were open when presentations were made and were closed only when the committee dealt with confidential information or discussed what conclusions might be made from the data at hand. Several members of PASS, including its Region IV vice president, Linda Goodrich, regularly attended the briefing sessions.

TABLE 1-1 FAA Briefers and Subjects

|

FAA Staff Member |

Subject of Briefing |

|

James Ballough, Director, AFS-1 |

AFS and AIR missions, ASI responsibilities, ASI staffing and history of staffing systems. |

|

Robert Caldwell, AFS -160 |

Informal information on many aspects of ASI staffing; no formal briefing. |

|

Deane Hausler, AIR |

Description of staffing approaches used in AIR. |

|

Kevin Iacobacci, AFS-160 |

Description and explanation of ASAM staffing model in AFS. |

|

Colleen Kennedy-Roberts, Manager, AFS-100 |

Informal contributions; no formal briefing. |

|

Rosanne Marion, Manager, AFS-160 |

Additional background on AFS mission and ASI work. |

Stakeholder Panels. The committee determined that, in order to better understand the ASI workload, discussions with various stakeholders— industry and other groups that are affected by the work of ASIs—would be useful. It was also important to ensure that the relevant groups had the opportunity to provide their viewpoints on the current and needed staffing levels of ASIs, as well as on factors that influence staffing levels.

The committee developed a list of questions to pose to stakeholder groups related to perceptions of ASI staffing, factors influencing ASI staffing, and outcomes of adequate and inadequate staffing levels that affected that particular constituency. These questions were distributed to all organizations that were invited to participate in the panels. Appendix B includes the list of questions posed to stakeholders.

After consultation with FAA staff and PASS representatives, as well as a general discussion in the committee, a number of stakeholders were identified. These included air carriers, aircraft manufacturers, general aviation and specialty aviation associations, maintenance providers, pilots and other workers’ associations, and consumer safety groups. Representatives from these organizations were invited to attend a meeting of the committee and provide a briefing or to submit a written response to questions posed by the committee. Table 1-2 lists those organizations that were invited to provide a briefing to the committee.

The organizations that accepted the invitation are shown in bold in the table. We made a good faith effort to reach a broad sampling of stake-

TABLE 1-2 Stakeholder Groups Invited to Provide Briefings

holders, but several interest groups whose inputs we solicited did not choose to participate, even after we made follow-up contacts. We understand that we may not have heard all relevant points of view, but we had no choice but to work with the information obtained from those who agreed to participate.

Briefings were presented at the committee’s meetings in March and June 2005. Table 1-3 lists the individuals providing briefings and the organizations they represented. A detailed summary of the themes from the briefings appears in Chapter 4.

Visits to ASI Work Sites. The committee requested assistance from the FAA headquarters staff to facilitate visits to several FAA field offices where ASIs are employed. We requested and received contact information and introductions for sites that would give us access to ASIs and managers representing the major categories of ASI jobs (operations, maintenance, avionics, and manufacturing) and serving major sectors of the industry, including air carriers (operating under FAR Sections 121 and 135), general aviation, and manufacturing. The facility managers selected the ASIs in the requested categories to be interviewed. Some of those interviewed were PASS representatives or individuals recommended by PASS.

The selection of sites for visitation did not follow a scientific sampling process, and the sites chosen were not necessarily representative of the universe of ASI positions or worksites. It was a convenience sample selected to educate the committee on the work of ASIs and the environments in which the work is done, and to help us understand a variety of points of view on ASI staffing.

The committee decided to provide all interview participants with an assurance of anonymity and keep their individual responses confidential. This was done to ensure that respondents could talk freely with the interviewers without fear of any negative consequences. Thus job titles and other information that would allow ASIs to be individually identified are not included here.

The committee developed a protocol to structure the conversations with ASIs and their managers to efficiently collect information relevant to the tasks. Committee members with interviewing expertise conducted pilot visits to two FAA sites, and the committee discussed and revised the protocol in light of what was learned on these initial visits. The final protocol is reproduced in Appendix B. Committee members then visited the remaining five sites and conducted individual and group interviews with operations, maintenance, and avionics ASIs and managers. Table 1-4 shows the sites and number of people interviewed at each. (We planned but were not able to complete a visit to interview manufacturing

TABLE 1-3 Organizations and Individuals Providing Input to the Committee

|

Organization |

Representative |

Title |

|

Aeronautical Repair Station Association |

Sarah McLeod |

Executive director |

|

Aerospace Industries Association |

Mike Romanowski |

Vice president, civil aviation |

|

Aircraft Electronics Association |

Paula Derks |

President |

|

Aircraft Mechanics Fraternal Association |

Maryanne DeMarco |

Legislative liaison |

|

Aircraft Owners and Pilots Association |

Melissa Rudinger |

Vide president, regulatory policy |

|

Air Line Pilots Association |

Charlie Bergman |

Manager, air safety and operations |

|

Federal Aviation Administration |

Kevin Iacobacci Deane Hausler |

AFS and AIR headquarters staff |

|

General Aviation Manufacturers Association |

Walter Desrosier |

Engineering and maintenance |

|

Individual safety consultant |

John Goglia |

Senior vice president, Professional Aviation Maintenance Association |

|

International Association of Machinists and Aerospace Workers |

David Supplee |

Director of IAM flight safety |

|

National Agricultural Aviation Association |

Andrew Moore |

Executive director |

|

National Air Carrier Association |

George Paul |

Safety and maintenance director |

TABLE 1-4 Flight Standards District Offices Visited and Number Interviewed per Site

|

Location |

Number Interviewed |

|

Baltimore, MD |

7 |

|

Columbia, SC |

4 |

|

Detroit, MI |

5 |

|

Fort Worth, TX |

7 |

|

Grand Rapids, MI |

5 |

|

Miami, FL |

3 |

|

Scottsdale, AZ |

8 |

inspectors at a manufacturing inspection district office.) The findings from these visits are discussed in Chapter 4.

Structure of the Report

This report is organized in an Executive Summary and five chapters. This first chapter provides the background of the study and explains the committee’s approach to its task. Chapter 2 discusses modeling and its applicability to the development of staffing standards for such organizations as the Flight Standards Service and the Aircraft Certification Service. Chapter 3 traces the recent history of staffing standards in these organizations and considers manpower and staffing models and methods used by other organizations. Chapter 4 examines factors to be considered in the development of ASI staffing standards and the challenges faced by any methodology applied to this task. Chapter 5 presents the committee’s findings and recommendations, including a discussion of issues and constraints that must be considered in weighing the implementation of alternative approaches.

Box 1-2 lists aviation-related and other acronyms relevant to the topics of this report.