3

Program Planning, Financing, and Coordination

The huge geographic scope, complexity, and cost of the Comprehensive Everglades Restoration Plan (CERP) necessitate a carefully planned and coordinated effort. Adequate funding, effective program planning mechanisms, and the support of stakeholders are all critical to the success of the CERP. Since 1999, substantial progress has been made in the coordination and program management elements of the CERP. This progress is outlined in detail in the 2005 CERP Report to Congress (DOI and USACE, 2005; see Box 3-1). This chapter highlights specific issues related to CERP project sequencing, delays in project scheduling, the project planning process, finances, and partnerships that have influenced or are likely to impact progress being made on restoring the natural system (see Statement of Task 1, Box S-1). Because project scheduling and financing are engineering issues that ultimately determine when natural system restoration will be initiated in various parts of the South Florida ecosystem (see Statement of Task 3), these issues are discussed here in detail.

CERP MASTER IMPLEMENTATION SEQUENCING PLAN

The Master Implementation Sequencing Plan (MISP) specifies the sequence in which CERP projects are planned, designed, and constructed. A detailed schedule for the 68 CERP project components over more than 30 years was originally set out in the Yellow Book (USACE and SFWMD, 1999). The current overall implementation schedule for the CERP (MISP version 1.0) was revised in 2005 based on updated project schedules (USACE and SFWMD, 2005d). This latest version of the MISP also includes the new scheduling of CERP projects under the state’s Acceler8 initiative (see Chapter 5, Box 5-3).

The MISP outlines construction milestones for CERP projects from 2005 until 2040 and groups the projects into seven 5-year bands by completion

|

BOX 3-1 CERP 2005 Report to Congress The Water Resources Development Act of 2000 (WRDA 2000) required the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) and the U.S. Department of the Interior (DOI) to report to Congress on the progress of the CERP once every 5 years. The first CERP congressional report was produced in 2005 and summarizes the progress to date along with forecasts for projects and funding for subsequent years. The 2005 Report to Congress includes sections devoted to outlining the bureaucratic structure of the restoration effort, project implementation, project coordination, progress toward interim goals and interim targets, and a financial summary. It also summarizes the progress made on both CERP and non-CERP projects (see Appendix A of this report). This committee reviewed the final draft of the CERP 2005 Report to Congress dated December 16, 2005 (DOI and USACE, 2005), to understand the perspective of those most closely involved with the restoration. Based on the report, it appears that the massive administrative and bureaucratic infrastructure needed to fully implement the CERP is now largely in place. The report notes that, in addition to agreements between the federal and state governments executed during the 2000-2004 period, the Programmatic Regulations for the CERP were finalized, and the MISP created. At the time of the report, final drafts of the Guidance Memoranda (USACE and SFWMD, 2005a), definitions of the pre-CERP baseline conditions (USACE and SFWMD, 2005c), and recommendations for interim goals and interim targets (RECOVER, 2005b) had been released. Taken together, these agreements and reports provide a means to assess the progress of the CERP in ecosystem restoration. The CERP 2005 Report to Congress concludes with a financial summary that outlines the total expenditures related to CERP through the end of fiscal year (FY) 2004 and that revises cost estimates made in original plans from 1999. The most recent total cost estimate for the CERP is $10.9 billion at October 2004 price levels. |

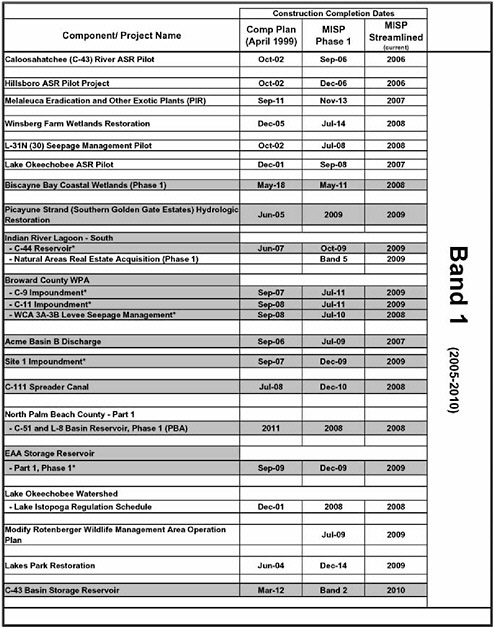

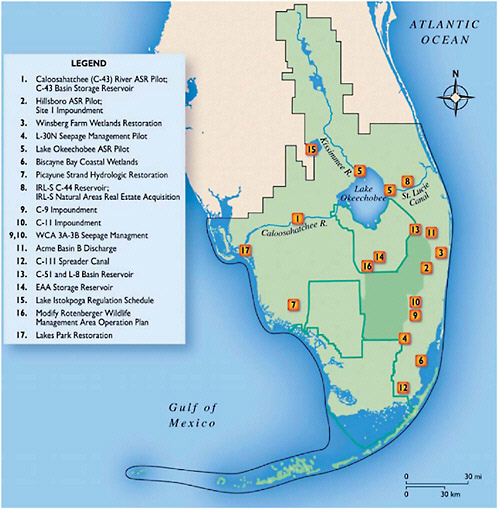

dates (see Appendix B for the complete MISP). Compared to the prior CERP scheduling approach that used specific project deadlines, the banding approach better reflects uncertainty in project milestone dates and offers more adaptability in the project development process and the ability to account for project dependencies. Band 1, comprising 2005-2010 (Table 3-1 and Figure 3-1), shows that construction is not expected to be finished on any of the CERP projects until 2006 at the earliest, when the completion of two pilot projects is expected. Aside from these pilot projects, estimated construction completion dates for CERP projects remain several years away, although significant planning and design efforts are under way. Overall, most CERP components are planned for completion in the first three bands (2005-2020), with fewer components scheduled for completion in the most

TABLE 3-1 Comparison of Construction Completion Dates from the Yellow Book and the Master Implementation Sequencing Plan, Version 1.0 for Band 1

FIGURE 3-1 Locations of Band 1 CERP project components. © International Mapping Associates.

NOTE: See Table 3-2 for complete project component titles.

distant time bands (2020-2040). Many of the early CERP projects focus on securing water storage before major projects are implemented to restore historical water characteristics (i.e., quality, quantity, timing, distribution, flow) to the natural system (Table 3-2). WRDA 2000 requires that state law quantify and protect the water from CERP projects designated for the natural system through the adoption of “water reservations.”1 However, decisions have not yet been made regarding how much of the added water storage capacity from each project will go to provide water to the natural system versus supplying water to meet urban and agricultural needs because modeling to quantify the benefits of these projects has not been completed. The CERP web site2 reports that approximately 80 percent of the water stored after full CERP implementation will be used for restoration of the natural system whereas 20 percent will be used to enhance agricultural and urban water supplies. Until the water reservation determinations have been legally established, the natural system benefits of the Band 1 water storage projects cannot be determined.

Scheduled completion dates for CERP projects have changed since 1999 when the initial plan was approved. For example, according to the MISP, of the 16 pilot projects and project components or phases that were originally anticipated to be completed by the end of 2005, all have been delayed until 2006 or later. Of the 21 pilot projects and project components or phases currently scheduled in the MISP for completion in the 2005-2010 period (Table 3-1), 10 were originally scheduled for this period, 4 were scheduled for later completion, 6 were scheduled to be completed by 2004, and 1 represents a newly scheduled project phase. The projects now scheduled for earlier completion are mostly ones contained in the Acceler8 program, such as the Biscayne Bay Coastal Wetlands and the C-43 Basin Storage Reservoir (see Box 5-2).

The Yellow Book recommended a series of pilot projects and major restoration projects for initial authorization to “expedite ecological restoration of the south Florida ecosystems” (USACE and SFWMD, 1999; Tables 3-3 and 3-4). All of the recommended pilot projects from the Yellow Book were authorized in WRDA 1999 or WRDA 2000. The authorized pilot projects will provide critical information to determine project feasibility and

|

1 |

The reservations of water for the natural system will be made by the South Florida Water Management District (SFWMD) pursuant to state law. The SFWMD will accomplish the reservations through the rule-making authority of their governing board. For more information, see http://www.sfwmd.gov/org/wsd/waterreservations/index.html. |

|

2 |

See http://www.evergladesplan.org/about/rest_plan_pt_08.cfm. |

TABLE 3-2 Primary Purposes and Reported Natural System Benefits of Project Components Scheduled for Completion in MISP Band 1 (2005-2010)

|

Band 1 Project Components |

Primary Purpose |

Reported Potential Natural System Benefits |

|

Caloosahatchee (C-43) River ASR Pilot |

Improved design and reduction of uncertainty |

Minimal. |

|

Hillsboro ASR Pilot Project |

Improved design and reduction of uncertainty |

Minimal. |

|

Melaleuca Eradication and Other Exotic Plants (PIR) |

Habitat restoration |

Enhance efforts to control the spread of Melaleuca and other exotic plants that are flourishing throughout the greater Everglades ecosystem. |

|

Winsberg Farm Wetlands Restoration |

Habitat restoration |

Created wetlands in developed area of Palm Beach County will provide habitat for wildlife and native plants. |

|

L-30N Seepage Management Pilot |

Improved design and reduction of uncertainty |

Minimal; construction will reduce seepage loss to east and save some water for Everglades National Park. |

|

Lake Okeechobee ASR Pilot |

Improved design and reduction of uncertainty |

Minimal. |

|

Biscayne Bay Coastal Wetlands (Phase 1) |

Habitat restoration |

Restore freshwater sheet flow towards Biscayne Bay thereby improving its freshwater and tidal wetlands, nearshore bay habitat, marine nursery habitat, oysters and the oyster reef community. |

|

Picayune Strand Hydrologic Restoration |

Habitat restoration |

Freshwater habitat restoration and estuarine salinity stabilization. |

|

Indian River Lagoon-South (IRL-S): C-44 Reservoir |

Water storage |

Moderate damaging freshwater discharges to Indian River Lagoon, thereby improving the ecology of the lagoon. |

|

IRL-S: Natural Areas Real Estate Acquisition (Phase 1) |

Habitat restoration |

Preserve natural habitat. |

|

Broward County Water Preserve Area: C-9 Impoundment |

Water storage |

Divert urban runoff into impoundments. |

|

Broward County Water Preservation Area (WPA): C-11 Impoundment |

Water storage |

Divert urban runoff into impoundments. |

|

Band 1 Project Components |

Primary Purpose |

Reported Potential Natural System Benefits |

|

Broward County WPA: WCA 3A-3B Seepage Management |

Seepage management |

Reduce water seepage losses from WCA 3A/3B. |

|

Acme Basin B Discharge |

Water storage |

Provide water and water quality treatment for Arthur R. Marshall Loxahatchee National Wildlife Refuge. |

|

Site 1 Impoundment |

Water storage |

Reduce water demands on Lake Okeechobee and Arthur R. Marshall Loxahatchee National Wildlife Refuge. |

|

C-111 Spreader Canal |

Habitat restoration |

Reestablish sheet flow in South Dade County. |

|

North Palm Beach County: C-51 and L-8 Basin Reservoir |

Water storage |

Improve timing and volume of discharges to Loxahatchee Slough and Lake Worth Lagoon and improve hydropattern in wildlife management area. |

|

Everglades Agricultural Area Storage Reservoir, Part 1, Phase 1 |

Water storage |

Improve timing of deliveries to WCA 2A and 3A and moderate high stages in Lake Okeechobee as well as water discharges to the estuaries from the lake. |

|

Lake Okeechobee Watershed: Lake Istokpoga Regulation Schedule |

Habitat restoration |

Enhance fish and wildlife habitat in Lake Istokpoga littoral zone. |

|

Modify Rotenberger Wildlife Management Area Operation Plan |

Habitat restoration |

Enhance plant and animal habitat. |

|

Lakes Park Restoration |

Habitat restoration |

Reduce exotic species and enhance watershed biodiversity in Hendry Creek. |

|

C-43 Basin Storage Reservoir |

Water storage |

Improve timing and water quality of freshwater discharges to Caloosahatchee Estuary. |

|

NOTE: Reported natural system benefits were obtained from the project descriptions and supporting project materials found at www.evergladesplan.org/pm/projects/project_list.cfm. The primary project purpose represents the committee’s judgment based on the same materials. Among the primary purposes, water storage could provide benefits to both the natural system and to the human environment, depending on the water reservations ultimately determined. Gray shading indicates those projects being constructed by the South Florida Water Management District. |

||

TABLE 3-3 Schedule of CERP Pilot Projects Initially Recommended in the Yellow Book

|

Project |

Planned Completion as of 1999 |

MISP 1.0 Schedule (2005) |

Estimated Cost (millions, in 1999 dollars) |

|

Lake Okeechobee Aquifer Storage and Recovery (ASR) Pilota |

2001 |

2007 |

$19 |

|

Hillsboro ASRa |

2002 |

2006 |

9 |

|

Caloosahatchee River Basin ASR Pilotb |

2002 |

2006 |

6 |

|

L-31N Seepage Management Pilotb |

2002 |

2008 |

10 |

|

Lake Belt In-Ground Reservoir Technology Pilotb |

2005 |

2015-2020 |

23 |

|

Wastewater Reuse Technology Pilotb |

2007 |

2015-2020 |

30 |

|

aAuthorized by WRDA 1999. bAuthorized by WRDA 2000. SOURCE: USACE and SFWMD (1999); DOI and USACE (2005). |

|||

aid in project design, making them necessary components of the adaptive management process. The extent of the delays for each pilot project is evident from comparison of the original planned completion dates (as of 1999) and the current MISP schedule (Table 3-3). The average delay of the six pilot projects is nearly 8 years. In general, the original deadlines from the Yellow Book for completing the pilot projects were probably overly ambitious, considering the scope of the scientific and engineering issues that need to be addressed and the federal process required to be completed before pilot projects could be implemented. Delaying the wastewater reuse pilot project may be reasonable because the technology is already well developed, and the projects this pilot is designed to inform are not scheduled to occur until 2020 or later. Delays in the expected completion of the Lake Belt in-ground reservoir technology pilot project may be of more concern, because the technology to create adequate seepage barriers to convert limestone quarries to water storage reservoirs has been neither developed nor tested. The L-31N seepage management pilot, however, needs to be initiated soon to prevent delays in the Everglades National Park seepage management project that it will inform. Progress and reasons for delays in the aquifer storage and recovery (ASR) pilot projects are discussed in detail in Chapter 5.

All of the Yellow Book’s initially recommended construction projects were also authorized in WRDA 2000 (Table 3-4), contingent upon congressional approval of the associated project implementation plans. Planned

TABLE 3-4 Schedule of the Initially Recommended CERP Projects from the Yellow Book

|

Project |

Part of Acceler8 or LOER? |

Planned Completion as of 1999 |

MISP 1.0 Schedule (2005) |

Estimated Cost (millions, in 1999 dollars) |

|

C-44 Basin Storage Reservoira |

Yes |

2007 |

2009 |

$113 |

|

Everglades Agricultural Area Storage Reservoirs Phase 1a |

Yes |

2009 |

2009 |

233 |

|

WCA 3 Decompartmentalization and Sheet Flow Enhancement—Part 1, which included: |

|

|

|

|

|

No |

2010 |

2015-2020 |

27 |

|

No |

2009 |

2010-2015 |

77 |

|

Site 1 Impoundmenta |

Yes |

2007 |

2009 |

39 |

|

C-9 Stormwater Treatment Area/Impoundmenta |

Yes |

2007 |

2009 |

89 |

|

C-11 Impoundmenta |

Yes |

2008 |

2009 |

125 |

|

WCA 3A and 3B Levee Seepage Managementa |

Yes |

2008 |

2008 |

100 |

|

C-111N Spreader Canala |

Yes |

2008 |

2008 |

94 |

|

Taylor Creek/Nubbin Slough Storage and Treatment Areaa |

Yesb |

2009 |

2010-2015a |

104 |

|

NOTE: LOER=Lake Okeechobee and Estuary Recovery; WCA=Water Conservation Area. aTen projects conditionally authorized by WRDA 2000. bThe Taylor Creek/Nubbin Slough Storage and Treatment Area Project has been accelerated as part of the LOER initiative (see Chapter 2), which was announced after the release of the MISP v. 1.0. The new estimated completion date is 2009. SOURCE: USACE and SFWMD (1999); DOI and USACE (2005). |

||||

completion dates for 6 of the 10 WRDA-authorized construction projects have been delayed since the original schedule was developed in 1999 (Table 3-4). Most of these initial projects are included in the Acceler8 program, and all Acceler8 projects are planned for completion within 2 years of the original Yellow Book schedule. The Nubbin Creek/Taylor Slough Storage and Treatment Area has been incorporated into the Lake Okeechobee and Estuary Recovery (LOER) initiative (see Box 2-2), and its completion has been accelerated to 2009—the same date as the original

Yellow Book schedule (SFWMD, 2005). Only 1 of the 10 projects conditionally authorized in WRDA 2000—Water Conservation Area (WCA) 3 Decompartmentalization and Sheet Flow Enhancement—Part 1 (Decomp)— has been substantially delayed. Although Decomp has been cited as the “heart of the restoration effort” (USACE and SFWMD, 2002) and exemplifies the removal of the canals and levees that contributed to the decline of the Everglades ecosystem, it is not part of Acceler8 or LOER. The projected completion for Decomp has now been delayed by up to 10 years (see Chapter 5 for further discussion on delays in Decomp). The delays to Decomp are of particular concern because the project has the potential to contribute substantial restoration benefits to large portions of the remnant Everglades ecosystem, including WCA 3 and Everglades National Park (USACE and SFWMD, 2002).3

The state of Florida deserves credit for reducing the delays in many of the early CERP projects through its Acceler8 and LOER initiatives. Nevertheless, even with Acceler8 and LOER, the CERP completion schedule is falling behind its original timetable. CERP implementation delays seem to result from a combination of factors:

-

budgetary and manpower restrictions,

-

delays in the completion of foundation (non-CERP) projects,

-

the extensive review and comment process involving partnering agencies and other stakeholders,

-

the need to negotiate resolutions to major concerns or agency disagreements in the planning process, and

-

a project planning and authorization process that can be stalled by unresolved scientific uncertainties, especially for complex or contentious projects.

Currently, a significant source of delay in CERP projects occurs during the project planning process, in which the framework for CERP projects outlined in the Yellow Book is transformed into specific project design details and construction plans.

The CERP planning process is discussed in more detail in the next section. To maintain broad support for the restoration, it is critical to place priority on projects delivering water to natural areas early in the CERP. This issue is discussed further in Chapter 5. A new approach for adapting the CERP planning and implementation process to accelerate natural system restoration is discussed in Chapter 6.

PROJECT PLANNING

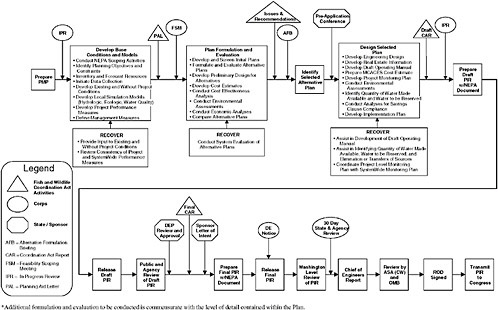

A project planning process has been put in place for the CERP (Figure 3-2). Through this process, the general framework envisioned in the Yellow Book is expected to result in specific project construction and operations plans consistent with existing regulations (e.g., Clean Water Act, National Environmental Policy Act, Endangered Species Act) and other CERP planning efforts. The 68 project components in the Yellow Book constitute the

FIGURE 3-2 CERP project development process.

SOURCE: Adapted from Appelbaum (2004).

inventory of all possible CERP projects that must then be developed into detailed project plans through the CERP planning process.

Initially, the Project Delivery Team (PDT) develops a project management plan (PMP) to outline the scope, activities, schedule, cost estimates, and agency responsibilities for the formulation, evaluation, and design of each project. The MISP sets the priority for a project to have a PMP created. After the completion and approval of the PMP by the USACE and the SFWMD, the PDT develops a project implementation report (PIR) for each project following instructions in the Final Draft Guidance Memoranda 1-4 (USACE and SFWMD, 2005a). These draft Guidance Memoranda describe the expected contents and supporting analyses required in the PIRs, leading to more detailed engineering design than was available during the development of the Yellow Book. The PIR includes an evaluation of alternative designs and operations for their environmental benefits in relation to costs, as well as engineering feasibility. Each PIR also includes detailed analyses that support the justification for a project being next in the queue for CERP implementation as opposed to being delayed to a later time. Each PIR must show conformance with the Savings Clause in WRDA 2000 (see Box 2-1), including a statement of the water reservation for the natural system and for other uses. The Restoration Coordination and Verification (RECOVER) program reviews the draft PIR, evaluates the benefits of project alternatives, and assesses the contribution of the project to meeting the overall goals of the CERP. RECOVER also evaluates the project’s contributions toward meeting the interim goals and interim targets (see Chapter 4). Figure 3-3 shows the detailed steps of the PIR process.

As of April 2006, 24 CERP project components had final PMPs and two CERP projects—Indian River Lagoon-South and Picayune Strand—had final PIRs that were under technical and budgetary review (see Box 3-2 and Figure 3-1). Draft PIRs have been completed for two other projects (Everglades Agricultural Area Reservoir and Site 1 Impoundment).

Once the state of Florida and Congress approve a PIR, authorization for construction may be sought. Ten CERP projects, however, received prior authorization through WRDA 2000, contingent on congressional approval of each project’s PIR (Table 3-3). Appropriations for funding then need to be secured. Any project that is to be considered part of the CERP, even those being advanced under Acceler8, must meet these planning requirements.

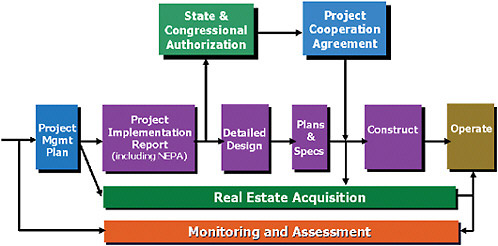

After authorization, if funding is received, a series of technical refinements, beginning with detailed design and ending with construction, take place in a sequence leading up to project operation (Figure 3-2). The project operations are expected to serve the purposes of the project as identified in

|

BOX 3-2 Summary of Projects with Completed PIRs As of April 2006, final PIRs had been produced for two projects—Indian River Lagoon-South (IRL-S) and Picayune Strand Restoration—and these PIRs were under administration review. Not surprisingly, both project plans included substantial changes from the framework plans laid out in the Yellow Book. Indian River Lagoon The IRL-S project, an approximately $1.2 billion component of the CERP (in 2004 dollars), is located northeast of Lake Okeechobee (Figure 3-1). The already authorized C-44 Basin Storage Reservoir is subsumed within the overall IRL-S project, to which are added the C-25 and C-23/C-24 North and South Storage Reservoirs. The original Yellow Book plan (USACE and SFWMD, 1999) was limited to these four storage reservoirs, but the project plans have since been significantly altered. The four storage basins are now proposed to provide 130,000 acre-feet of water storage, a substantial decrease in storage from the 389,000 acre-feet of storage proposed in the Yellow Book. An additional 65,000 acre-feet of storage are proposed through wetland restoration and utilization of three natural storage areas on 92,000 acres of land and in four new stormwater treatment areas. Finally, 7,900,000 cubic yards of muck will be dredged from the St. Lucie River and Estuary to provide 2,650 acres of clean substrate within the estuary for recolonization of marine organisms. The original Yellow Book plan aimed to reduce damaging flows to the St. Lucie Estuary and the Indian River Lagoon while also providing water supply for agriculture, thereby reducing demands on the Floridan aquifer. However, the PIR included added benefits for enhanced phosphorus and nitrogen reduction, improved estuarine water quality, restored upland habitats, increased spatial extent of wetlands and natural areas, and more natural flow patterns (USACE and SFWMD, 2004). The 2004 cost estimates for this project have increased by $440 million (or 54 percent) above those in the 1999 Yellow Book, reflecting both inflationary increases and $240 million in project scope changes (DOI and USACE, 2005). Picayune Strand Restoration A second major project for which the PIR has been completed and is under review is the Picayune Strand Restoration. Located in western Collier County (Figure 3-1), the project will restore and enhance more than 50,000 acres of wetlands in Southern Golden Gate Estates, an area once drained for development. The project will also improve the quality and timing of freshwater flows entering the 10,000 Islands National Wildlife Refuge, while maintaining flood protection for neighboring communities. The project includes a combination of spreader channels, canal plugs, road removal, pump stations, and flood protection levees. The project scope changes (e.g., additional road removal, larger pumps to provide additional flood protection), inflationary increases, and the failure to account for land acquisition costs in the original project cost estimates have led to an increase in costs from $15.5 million in the original Yellow Book to $349 million (DOI and USACE, 2005; USACE and SFWMD, 2005b). This project is one of the most significant for increasing the spatial extent of natural wetlands. |

the PIR and be consistent with the Savings Clause and the determination of water reservations. Also, necessary legal agreements governing local cooperation must be secured before construction can begin. As operations are initiated, monitoring is continued in support of an adaptive management program (see Chapter 4). However, it remains unclear, once projects are constructed, whether the envisioned adaptive management approach will be limited to fine-tuning individual project operations. Ideally, what is learned in this process also will be used to inform the planning and design of future projects.

There are several points in this process where delays might be anticipated. In the development of the PIR, technical and scientific uncertainties may need to be resolved for the PIR to meet the evaluation guidelines. Conflicting stakeholder and intergovernmental views over the Savings Clause and water reservations may need to be reconciled. Questions also may be raised about the quality of the technical analysis and over whether the project as proposed makes a contribution to the CERP goals. Even if authorization is secured, federal funding may not follow. Indeed, federal funding delays at least partly explain the state’s Acceler8 initiative and the changes from the 1999 CERP project schedule to the latest MISP. Funding issues are discussed further in the next section.

Ambiguities in the rules governing the current planning process may be a barrier to timely completion of the PIRs and to the execution of an effective adaptive management program. For example, each PIR project team must justify any investment using monetary and nonmonetary benefits, but it is not clear what these benefits may include. The regulations offer no specific instruction on how to measure such benefits, except to say that benefit measures should be able to be assessed and predicted and should be consistent with performance measures used to develop CERP interim goals and interim targets. A systematic approach to analyze the costs and benefits across multiple projects in support of plan formulation is notably lacking in the project planning process. Without such a process, it is not clear how the objective to optimize system benefits can be achieved by each PIR team without any systematic consideration of the planning of other PIR teams. Also, it appears as if predictions of benefits and costs by each PIR team must be made with certainty to satisfy stakeholders and decision makers, and contentious project planning issues cannot be resolved until the predicted outcomes can be ensured. However, this expectation of scientific certainty denies the CERP premise that there is much scientific uncertainty that can be reduced only by another CERP imperative—adaptive management. In Chapter 6, the committee proposes adjustments to the planning process that

can address concerns regarding uncertainty. However, the committee was unable to fully explore the issue of systemwide CERP planning within the time constraints of this review and hopes this issue can be addressed in future reports of this committee.

FINANCING THE CERP

The overall cost of the CERP is planned to be divided equally between the federal and nonfederal (i.e., state and local) governments. The current estimate of CERP cost (in 2004 dollars) is $10.9 billion (Table 3-5), an increase from the original estimate of $8.2 billion in 1999. The current total includes estimated program coordination costs over the lifetime of the CERP of $500 million that were not included in the original 1999 budget. In addition, estimated project costs have increased from $7.8 billion to $9.9 billion, reflecting $1.5 billion in inflationary increases and $571 million in project scope changes for the two projects with approved PIRs (see Box 3-2

TABLE 3-5 CERP Cost Estimate Update Summary

|

|

Updated Cost Estimate Summary (in millions, rounded) |

|

|

|

Oct 1999 Price Level |

Oct 2004 Price Level |

|

Projectsa |

$ 7,820 |

$ 9,881 |

|

Adaptive Assessment and Monitoringb |

$ 387 |

$ 496 |

|

Program Coordinationc |

$ 0 |

$ 500 |

|

TOTALd |

$ 8,207 |

$ 10,876 |

|

aOctober 1999 price level information from the Central and Southern Florida Project Comprehensive Review Study, Final Integrated Feasibility Report and Programmatic Environmental Impact Statement (Yellow Book), Volume 1, p. 9-56, Section 9.9.1, Initial Costs, and p. 9-57, Table 9-2, Estimated Initial Cost for Construction Features. It also includes scope changes totaling approximately $571 million for IRL-S and Picayune Strand projects per approved decision documents. bOctober 1999 price level information from the Yellow Book, Volume 1, p. 9-56, Section 9.9.2, Adaptive Assessment and Monitoring Costs, and p. 10-31, Figure 10-6, Line 4, Restoration and Coordination Verification Team. cAdded per WRDA 2000 requirements. dThis table reflects October 2004 dollars using the Office of Management and Budget inflation indices based on CERP Plan (April 1999) or authorized project costs contained in decision documents. Table 9-1 of the CERP Report dated April 1999 identifies the estimated real estate to be acquired to implement each project at the time of the report, while Table 9-2 provides the cost estimates for this real estate. The final real estate requirements for each project may vary from what was shown in Table 9-1 due to a refinement of the real estate needs during PIR development and detailed design. SOURCE: Adapted from DOI and USACE (2005). |

||

TABLE 3-6 CERP Cumulative Creditable Expenditures Through Fiscal Year 2004 (in millions)

|

|

USACE |

SFWMD |

Total |

|

Projects |

56.78 |

40.41 |

$ 97.19 |

|

Adaptive Assessment and Monitoring |

5.86 |

10.01 |

$ 15.87 |

|

Program Coordination |

41.68 |

55.56 |

$ 97.14 |

|

TOTAL |

104.32 |

105.88 |

$ 210.2 |

|

Cost Share Percentage |

49.6% |

50.4% |

|

|

SOURCE: DOI and USACE (2005). |

|||

and Table 3-5). Estimated costs for monitoring and assessment have increased from $387 million to $496 million, largely reflecting inflation (DOI and USACE, 2005). If delays continue in the planning and approval process, the cost of the CERP will continue to increase, especially for land acquisition costs.

In administering and reporting on the CERP, the USACE uses the notion of creditable expenditures (DOI and USACE, 2005). Creditable expenditures are those CERP expenditures that the USACE judges appropriate to be credited toward the cost-sharing agreement for the project. According to the 2005 Report to Congress, creditable expenditures through 2004 ($200 million) were very nearly evenly shared between the federal and state governments (Table 3-6), but they were less than 2 percent of the total cost estimate of $10.9 billion for the entire plan. These creditable totals do not include expenditures for the acquisition of lands anticipated to be needed for CERP implementation. The 2005 Report to Congress reported CERP land acquisition expenditures of $800 million, $259 million, and $32 million from the state of Florida, federal agencies, and local funds, respectively.

As Florida’s Acceler8 program moves forward over the next 4-5 years, the state will spend a significantly greater proportion than the federal government on CERP projects. Whether the Acceler8 project expenditures will be creditable to the CERP cost-sharing agreement is not yet determined. Anticipated funding required to support the Band 1 (2005-2010) activities is $3 billion, of which the USACE will fund 21 percent (Table 3-7). Although the CERP is a joint undertaking, the financial responsibility in the early period has been and will be borne primarily by the state.

The CERP remains the focus of natural system restoration efforts in

TABLE 3-7 CERP Funding Required to Support the MISP in Band 1, FY 2005-FY 2009 (in millions)

|

|

FY05 |

FY06 |

FY07 |

FY08 |

FY09 |

5-Yr Total |

|

USACE |

$ 59 |

$ 68 |

$ 118 |

$ 180 |

$ 200 |

$ 625 |

|

SFWMD |

$ 329 |

$ 329 |

$ 288 |

$ 737 |

$ 767 |

$ 2,450 |

|

Palm Beach Countya |

$ 0.97 |

$ 1.88 |

$ 2.62 |

$ 0 |

$ 0 |

$ 5.47 |

|

Lee Countya |

$ 0.05 |

$0.09 |

$ 0.09 |

$ 0 |

$ 0.02 |

$ 0.25 |

|

GRAND TOTAL |

$ 389 |

$398 |

$ 409 |

$ 917 |

$ 967 |

$ 3,080 |

|

aAnticipated funding for Palm Beach and Lee Counties are from associated project PMPs. SOURCE: Adapted from DOI and USACE (2005). |

||||||

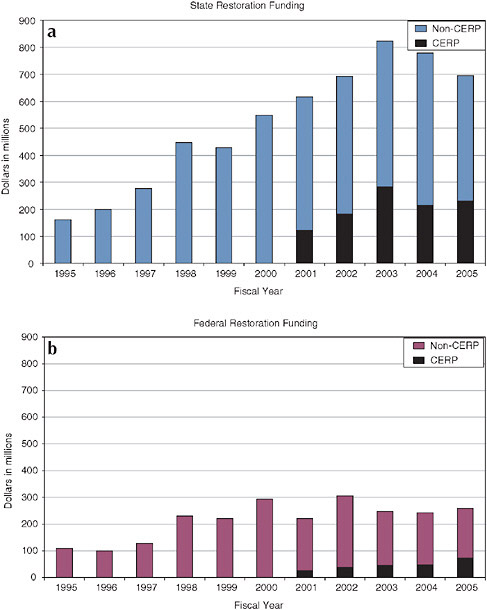

South Florida, but numerous non-CERP activities are also under way (see Box 2-2). Figure 3-4 shows that the bulk of expenditures to date have involved non-CERP activities. Considering both CERP and non-CERP restoration activities, the state of Florida’s overall expenditures on restoration of the South Florida ecosystem has been consistently larger than federal expenditures from 1995 until 2005, with peaks in FY 2002 and 2003 (Figure 3-4).

The overall cost of the CERP is uncertain, but for two main reasons it is likely to increase substantially in the next decades. First, project scope and costs are still highly uncertain, particularly for all the projects that do not have final PIRs, and project scope changes can be expected. Some of these changes will be associated with technical issues such as the performance of ASR (NRC, 2002a), but other changes may be due to expansion of the project objectives. As noted above, project scope changes for only two projects (see Box 3-2) have already increased CERP cost estimates by $571 million. However, it is unclear whether these scope changes could reduce the costs of other CERP projects, because there does not seem to be a formal process in place to evaluate increased investment costs against the systemwide benefits, assuming that funding is not unlimited. Second, price inflation can be expected, especially for land acquisition and construction materials, such as cement. Land prices have risen substantially due to development pressures since the inception of the CERP. For example, agricultural land values in Florida increased 50 to 88 percent (depending on the land-use type) from 2004 to 2005 (Reynolds, 2006). The current cost estimate for CERP is in 2004 dollars, so the actual dollar expenditures will be higher solely due to the effects of inflation.

FIGURE 3-4 (a) State and (b) federal funding for Everglades restoration, FY 1995-FY 2005 (including CERP and non-CERP activities).

NOTE: Both CERP and non-CERP totals include funding for land acquisition for projects not yet authorized. As a result, the totals for CERP spending differ significantly from those in Table 3-6.

SOURCE: Data collected from the South Florida Ecosystem Restoration Program FY 2000, 2001, and 2006 Cross-Cut Budgets (SFERTF, 2000b, 2001, 2006).

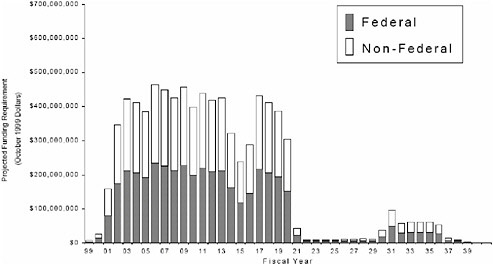

FIGURE 3-5 Projected federal and nonfederal funding required to support the CERP in 1999 dollars, as described in the Yellow Book.

SOURCE: USACE and SFWMD (1999).

Even without scope changes in the CERP, a major increase in federal expenditures will be needed to accomplish timely completion of CERP project commitments. Planned USACE expenditures for FY 2005 to FY 2009 average only $125 million per year (DOI and USACE, 2005), which falls far short of the federal funding anticipated in the original CERP implementation plan (Figure 3-5). Current planned federal expenditures are also not keeping up with the increases in expected costs. Even if federal costs were spread equally over 30 years, which is contrary to both the MISP schedule and investment strategies for most major construction projects, the federal share would be about $180 million/year, assuming no additional increases due to inflation or scope changes.

In essence, the state is bearing the major burden of funding the portions of the CERP that are currently being implemented. If federal funding for the restoration does not increase, most of the early CERP efforts will be focused on the estuaries, Lake Okeechobee, water storage, and seepage control (see Table 3-2 and Figure 3-1), and some projects that directly benefit federal lands, such as Decomp and Everglades National Park seepage management, may be further delayed. Nevertheless, increased federal funding may be difficult to achieve, because there are increasing pressures on the federal

water resources budget for other water resources projects of national importance. The state’s accelerated financial contributions to the CERP have clearly infused new momentum in the restoration program. However, the associated imbalance in funding jeopardizes the federal and state partnership envisioned for the CERP.

MAINTAINING PARTNERSHIPS

The restoration of the Everglades rests on a fragile coalition of partners who agree in principle on the overarching goals of the CERP. There are 66 signatories to the document that formally established the 3 broad goals and 68 project components of the CERP. Agreement in principle on a document with such lofty goals and such a bold vision for the people and resources of South Florida is in and of itself an important accomplishment. The agreement occurred in spite of a history of clashes in agency cultures, disagreements among political jurisdictions, and fundamental differences in philosophy between environmentalists and developers that have characterized Everglades issues.

Reaching consensus on the CERP goals and their wording, as well as the conceptual Yellow Book plan, was the result of long and protracted negotiations that required compromise from all parties to the agreement. The give and take that ultimately produced the CERP and the historical differences among many of the partners provided ample reason for this to be a coalition vulnerable to inefficiency in processes, redundancy in effort, and mistrust of intentions and desires. Other than the venerable notion of “getting the water right,” virtually every signatory may find some part of the CERP with which to disagree, and they have different views on the trade-offs that will and must be made as plan implementation begins. Despite these factors that are working against the partnership of the CERP, the coalition has held together and slow progress is being made to restore the South Florida ecosystem.

Aside from all the technical and scientific issues, the paramount challenge CERP faces, as expressed in the 2005 Report to Congress (DOI and USACE, 2005), “is to move forward through implementation with the continued support of the stakeholders.” From the beginning, there have been healthy disagreements among the stakeholders and participating agencies over a broad range of issues. For example, some stakeholders have asserted that there has been an undue emphasis in the early CERP implementation schedule on water supply projects at the expense of those that will more quickly enhance the natural environment (Grunwald, 2006; Sierra Club, 2004).

Although the partners could reach agreement in principle at the front end of the CERP on its overall goals, this consensus is now being bedeviled by the hard trade-offs among uses of water and the need to make water reservations to secure those uses over time as specific projects are being planned. For example, some stakeholders oppose filling canals because they provide ideal bass fishing habitat (Shupp, 2003; Waters, 2002). Other stakeholders argue that decompartmentalization projects are at the heart of the restoration effort and are being unduly delayed because of a lack of leadership and a capitulation to the demands of special interest groups (Estenoz, 2002). Still others suggest that the quality of the water in the system is not being adequately addressed and that it is illegal to move polluted water from one part of the system to another (Richey, 2004).

Of the many partnerships, the most important is that between the state of Florida in the form of the SFWMD and the USACE. The USACE and the SFWMD have worked closely for decades on the construction, maintenance, and operation of the Central and Southern Florida Project. The modifications of the project through the CERP, however, have required an unprecedented degree of coordination and complexity. The heightened sense of urgency, intense political interest at the state and federal levels, large sums of money required over multiple decades, and need for coordination across a broader range of interest groups have made it more difficult to keep this important partnership intact (Pittman, 2005).

The state’s Acceler8 initiative is an example of how the partnership between the USACE and the state is being tested. Acceler8 was initiated by the state in the fall of 2004 as a way to speed progress on the CERP (see Chapter 5 for a detailed discussion of Acceler8). The Governor announced Acceler8 as a $1.5 billion initiative designed to complete 11 CERP components and 3 additional non-CERP restoration components by 2010. In addition to accelerating the pace of selected projects, the state committed early funding for the projects and assumed design and construction responsibilities normally conducted by the USACE. Acceler8 was viewed cautiously by some environmental groups and other CERP partners and has been characterized as a way to move control of the CERP from the federal to the state level (Grunwald, 2006). Acceler8 has not only raised questions by some of the ancillary partners to the CERP but has also been approached cautiously at the regional and federal levels of the USACE (Morgan, 2005). For example, in a letter commenting on a variety of complex issues involving the state-federal partnership, the Deputy Assistant Secretary of the Army, George S. Dunlop, stated:

The Congress specifically required in section 601 of WRDA 2000 that all CERP projects, except those specifically authorized, are to be submitted to Congress for authorization. This is not an Army policy that can be changed unilaterally. The initial suite of projects under SFWMD’s “Accelerate Program” must be made part of the CERP, through Congressional authorization, in order for the Army to be able to consider giving the SFWMD credit for qualifying implementation costs…. Congress, through both the authorizations and appropriations processes, must approve and fund new construction starts, as OMB and Congress have insisted for even the simplest projects (Dunlop, 2005).

In addition to these legal concerns, the amount of money being committed by the state to the Acceler8 projects has thrown the federal-state partnership into disequilibrium because projects of particular importance to the state have now moved to the front of the CERP project list. The Acceler8 and LOER initiatives reflect the state’s priorities for restoring certain areas (Lake Okeechobee and the northern estuaries) over those areas under federal stewardship (e.g., Everglades National Park). Some stakeholders have also questioned whether the water storage provided by the Acceler8 projects will benefit federal interests (Sheikh and Carter, 2005). The order in which projects are funded is becoming of increasing concern to the CERP partners as questions surface regarding the possibility of insufficient funding to complete the entire CERP. If the political and financial support for the CERP wanes, it is likely that the trust among the signatories will also wane and with it hope for restoration of the South Florida ecosystem.

With the CERP only in its fifth year and no projects actually completed, it is highly likely that the partnership will see more rather then fewer tests of its cohesiveness. One of the primary reasons why there was great hope for the Everglades restoration 5 years ago was that groups on all sides of the issue were able to come together and form a partnership focused on a common but highly general goal and a promise that adequate funding would be available to address the many preferences of a multiplicity of stakeholders. Today the partnership remains intact but strained (Graham, 2006). In the end, success will require cooperation among a disparate group of organizations with differing missions as the broad goal of getting the water right is more precisely defined and budget limitations at best delay project implementation and at worst require a rethinking of the CERP project portfolio.

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

The large size of the South Florida ecosystem as well as the cost, complexity, and number of years required to complete the CERP necessitates that the restoration effort be carefully planned and coordinated. This chapter highlights several important planning, financing, and coordination issues that influence the progress being made on natural system restoration.

The original project implementation schedule from the Yellow Book was recently revised in the MISP. The new 5-year banding approach is a planning mechanism that offers adaptability in the project development process and accommodates uncertainty in achieving project milestone dates. Yet, scheduled completion dates for CERP projects have changed notably since 1999, when the CERP was approved. Estimated restoration costs have increased significantly during the first 6 years of the CERP, and disagreements among restoration stakeholders have emerged as the implementation phase of CERP is beginning. The CERP thus now faces the dilemma of moving forward in the face of delays, increasing costs, and disagreements among the very partners that created the bold plan for restoring the Everglades.

Although progress has been made in the planning, coordination, and program management functions required to implement the CERP, there have been significant delays in the expected completion dates of several construction projects that contribute to natural system restoration. Between 2000 and 2004 the USACE and SFWMD largely focused on developing a complex coordinating structure for planning and implementing CERP projects. However, while the management structures were being refined, all 10 of the CERP project components that were scheduled for completion by 2005 were delayed. Additionally, six pilot projects originally scheduled for completion by 2004 are expected to be delayed on average by 8 years. The delays seem to be the result of a number of factors, including budgetary and manpower restrictions, the need to negotiate resolutions to major concerns or agency disagreements in the planning process, and a project planning process that can be stalled by unresolved scientific uncertainties, especially for complex or contentious projects. The state’s Acceler8 program promises to improve the timeliness with which some projects are completed. However, the project that will provide substantial benefits to Everglades National Park (Decomp) is not included in Acceler8 and is instead now projected to suffer the longest delay of all the projects conditionally authorized under WRDA 2000.

Federal funding will need to be significantly increased if the original CERP commitments are to be met on schedule. Inflation, project scope changes, and program coordination expenses have increased the original cost estimate of the CERP from $8.2 billion (in 1999 dollars) to $10.9 billion (in 2004 dollars). Further delays will add to this increase, particularly because of the escalating cost of real estate in South Florida. Despite these cost increases, current planned federal expenditures for FY 2005 to FY 2009 fall far short of even those envisioned in the original CERP implementation plan. Although the CERP is intended to be a 50/50 cost-sharing arrangement between the federal and nonfederal (state and local) governments, federal expenditures from 2005 to 2009 are expected to be only 21 percent of the total. If federal funding for the CERP does not increase, major restoration projects directed toward the federal government’s primary interests (e.g., Everglades National Park) may not be completed in a timely way.

A significant challenge for the CERP is to implement the plan in a timely fashion while maintaining the federal and state partnership and the coalition of CERP stakeholders. Although there is consensus on the broad goals of the CERP there is disagreement among the agency partners and stakeholders on the timing and details of the myriad components of the program. One particular concern expressed by stakeholders is whether the water supply goals of the CERP are being unduly emphasized in the current CERP implementation plan at the expense of the natural system restoration goals. Of the many partnerships, the most important is that between the state of Florida and the USACE. The state’s Acceler8 initiative has been lauded for moving the CERP forward, but it has raised concerns about disproportionate funding and control by the state over the implementation of the program. In the end, success will require cooperation among a disparate group of organizations with differing missions as the broad goal of getting the water right is more precisely defined.