7

Balancing Choices: Supporting Consumer Seafood Consumption Decisions

This chapter presents Step 3 (see Box 5-1) of the process for designing consumer guidance on balancing benefits and risks associated with seafood consumption. This step focuses on the design and evaluation of the guidance program itself, including the format of the guidance; its communication through media, health care partners, and other channels; and mock-up examples of ways to integrate the benefit and risk considerations from previous chapters into consumer guidance. The chapter also discusses other communication and decision-support design considerations.

INTRODUCTION

The goal of this chapter is to advise agencies on how to develop a consumer seafood information program to support consumers who are trying to balance benefits and risks in their seafood consumption decisions. Such advice necessarily builds on an assessment of the benefits and risks, as well as an assessment of what decisions consumers actually face, and how they currently approach those decisions. A related and essential element of the process is use of the best available social and behavioral science research on the design of effective communications programs and messages to inform consumer benefit-risk decisions. In addition, we present several specific options for informing seafood consumption decisions, in order to highlight the features of alternative formats for informing consumers’ seafood consumption decisions for themselves and their families.

While there is a role for simple slogans and overall guidance to the general population, the committee believes that it cannot be emphasized

too much that communications tailored for specific audiences are likely to be more effective and thus are an important element in communications programs. This is especially important for benefit-risk choices where target population groups differ in their risk susceptibility, and in the degree to which they are likely to benefit. For both education and marketing, understanding the audience and targeting it appropriately are critical.

A successful communications program starts with clear objectives and measurable goals, and includes the steps outlined in the two preceding chapters followed by implementation and evaluation, as discussed below. The development strategy should be iterative, such that program evaluation is built into the program from the outset and used to refine it over time. One widely used health communications program planning document, the National Institutes of Health “Pink Book” (SOURCE: http://www.cancer.gov/pinkbook), suggests these components for a health communications program plan: a general description of the program, including intended audiences, goals, and objectives; a market research plan (i.e., for researching the consumer context and choice process); message and materials development and pretesting plans; materials production, distribution, and promotion plans; partnership plans; a process evaluation plan; an outcome evaluation plan; a task and timetable; and a budget.

For demonstration purposes, the committee takes as a working objective the facilitation of consumer use of information for decision making and balancing choices, for a wide variety of consumers. Corresponding measurable end points would be increased awareness of both benefits and risks of seafood consumption, and increased ease of access and usability of seafood benefit-risk information.

Table 6-2 in Chapter 6 provides a summary of the current seafood consumption information environment. Opportunities for improving the current information environment include: (1) providing more comprehensive and systematic evaluation of current consumer seafood information and information environments for target populations (“marketing research”); (2) increasing the emphasis on benefits of seafood consumption; (3) assessing the overall role of state advisories in consumer seafood consumption decisions, taking into account their limited reach; (4) increasing the availability of quantitative benefit and risk data for seafood consumption, and addressing any errors in how quantitative benefit and risk information is used in interactive online consumer guidance; (5) increasing the use and usefulness of point-of-purchase displays; and (6) developing partnership programs.

Notably, while US federal and state agencies provide websites for consumers (e.g., http://www.foodsafety.gov/~fsg/fsgadvic.html; http://health.nih.gov), these do not currently provide interactive online guidance; other parties are now providing quantitative risk information, as discussed in Chapter 6. Much has been written about program evaluation (CDC, 1999;

Mark et al., 2000; Ryan and DeStefano, 2000) and the evaluation of communications (Schriver, 1990; Spyridakis, 2000); the paucity of information available regarding both formative (e.g., the Food and Drug Administration focus groups) and summative (e.g., overall effects on attitudes or consumption) evaluation of national seafood consumption advisories suggests that agencies should devote additional attention and resources to evaluation. The committee touches on the importance of evaluation in the context of partnerships, to assess whether communications are appropriate and effective for target populations.

STEP 3: DESIGNING COMMUNICATIONS TO SUPPORT INFORMED DECISION-MAKING

Interactive Health Communication

In seafood consumption, “one size does not fit all,” and messages about consumption often have to be individualized for different groups. There is a need to consider developing tools for consumers such as web-based, interactive programs that provide easy-to-use seafood consumption decision tools. Real-time, interactive decision support that is easily available to the public has the potential to increase informed actions for some portion of the population. In the absence of federal investment in such tools, some organizations have invested in online mercury calculators or consumption guides (Table 6-1). Many of these focus solely on risks from seafood consumption, and while well-intentioned, may be providing misleading information, for example, by interpreting the Reference Dose (RfD) as a “bright line” to determine whether consuming seafood puts a consumer at risk.

One model for developing comprehensive consumer tools is a health risk appraisal (HRA) that would allow individuals to enter their own specific information and would provide feedback in the form of appropriate information or advice to guide the user’s health actions, such as seafood consumption. There are a myriad of health risk appraisal tools commercially available; of those in the public domain the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has extensive experience in the development and use of HRAs (SOURCE: http://www.cdc.gov). In order to be most useful and appropriately directed, tools such as the HRA must be based on a body of knowledge that substantiates both benefits and risks. This kind of approach can be seen in the Clinical Guide to Preventive Services from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), which adopted recommendations based on medical evidence and the strength of that evidence in practice (USPSTF, 2001–2004).

The Clinical Guide to Preventive Services is an example of an interactive health communication approach to providing one-on-one guidance, along

with the degree of evidence for that guidance, which is used to categorize a spectrum of recommendations. These tools are generally not set up to provide information to individuals, but rather to public health practitioners and individual care providers. Their recommendations are evidence-based but not easily translatable to the lay community. Although the Clinical Guide to Preventive Services is aimed toward practitioners, AHRQ has tried to make it understandable to the general public—e.g., if you are over 50, and have a risk factor, then get a mammogram.

A more coordinated approach is needed for developing and disseminating evidence-based recommendations to health care practioners that can then be provided to consumers. Such recommendations should be updated on a continuous, rotating basis, to allow for more rapid translation of science to practice. Where HRA tools are targeted for intermediaries who are experts in their own right, guidance or additional tools are necessary to help them translate and target information for consumers. The Clinical Guide to Preventive Services has a handbook that attempts to provide user-friendly tools to help providers translate and target information to consumers. If the goal is to guide consumption decisions that balance benefits and risks, there needs to be a similar translation mechanism because of the limited and continuously evolving knowledge base concerning seafood benefits and safety. Currently, consumers are receiving piecemeal information about methylmercury and persistent organic pollutants such as dioxins and polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs); for the most part, that information is not pulled together sufficiently to facilitate consumers’ understanding it in context and thus being able to use it to inform their choices (see Table 6-2). (Also see Chapter 6 for discussion of the effectiveness of online nutrition information.)

A general framework for developing this kind of communication is a consumer checklist that engages the user in interactive identification of his or her benefit-risk factors, and uses that information to produce a tailored benefit-risk estimation and associated recommended actions. Determining how to communicate the resulting estimates and actions requires a series of judgements, including whether and how to represent this information as text, numbers, or graphics. Empirical testing of the effects of the final tool is essential, given the difficulties of predicting the effects of communications on individual consumers, or even specific target populations.

Decision Support for Consumers

The committee’s balancing of the benefits and risks of different patterns of seafood consumption for different target populations resulted in the analysis presented in Chapter 5. This type of expert identification of the characteristics that distinguish target populations who face substantially dif-

ferent consequences from seafood consumption is an important component of audience segmentation and targeting.

If a target population believes they are exempt from general advice because of some specific condition, they may either ignore the available advice or interpret it in unanticipated ways. The spillover effects discussed in Chapter 6 illustrate the kinds of problems that may arise. While expert recommendations such as those summarized in Chapter 5 could, in theory, be used directly by federal agencies as advice to consumers on seafood consumption, such advice is unlikely to be effective if it ignores consumers’ contexts and information needs.

As discussed in Chapter 6, there are multiple reasons why expert benefit-risk analyses alone comprise an insufficient communication design strategy. Examples include when consumers distrust experts, when there are widespread misconceptions about a risk or benefit, or when experts use technical jargon that makes their reasoning opaque to nonexperts. Some consumers may want more information, and some will want to be able to independently verify experts’ advice.

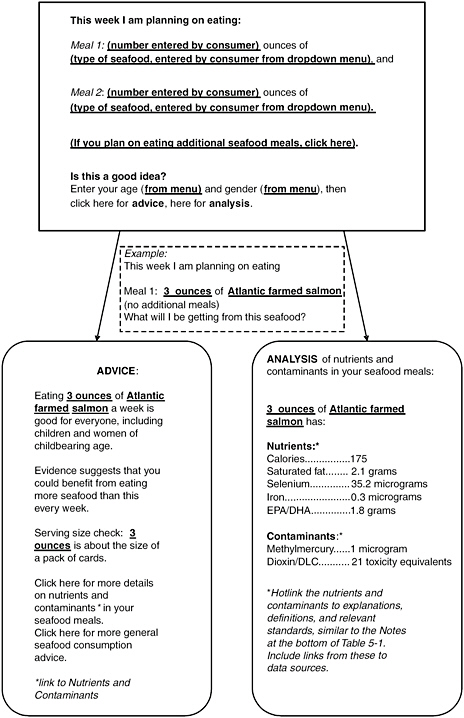

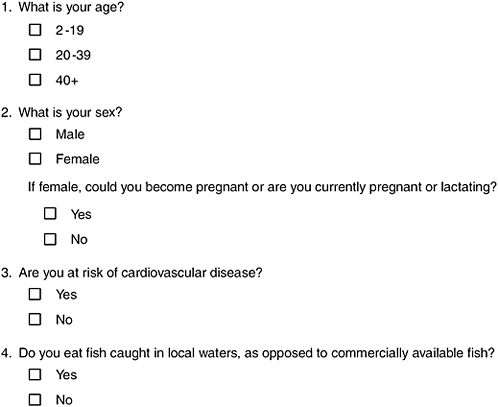

One previously tested consumer-centered approach to providing information is the development of decision support focused on the decisions and decision contexts faced by consumers, as discussed in Chapter 6. Through a brief set of questions, a decision pathway can segment and channel consumers into relevant target populations in order to provide benefit and risk information that is tailored to each group, as illustrated in Figures 7-1 and 7-2.

Figure 7-2 includes a separate question about cardiovascular health, which differentiates it from Figure 5-2. This question is included because the committee anticipates that the many recommendations and guidelines specially targeting higher eicosapentaenoic acid/docosahexaenoic acid (EPA/ DHA) consumption for those with cardiovascular health concerns may have created a belief in that target population that they would benefit more than others from high EPA/DHA consumption. As is evident from the recommendations in both Figure 5-2 and 7-2, the committee’s analysis does not support this distinction. This assumption about cardiovascular patients’ beliefs would need to be verified empirically before it was included as part of a communications program.

Alternative formats for presenting information can serve the interests of consumers who desire different levels of information as inputs to their decision-making, and provide those most interested with additional insight regarding the quality of information, including uncertainties. Alternative guidance structures might be relevant for consumers focused on different goals and decisions, such as the estimated benefits and risks of eating a specific seafood meal, as illustrated in Figure 7-3. Figure 7-3 uses consumption of one 3-ounce serving of Atlantic farmed salmon as an example of the type of information that could be presented with this tool. The committee notes

FIGURE 7-1 Example of set of questions to identify benefit-risk target populations for seafood consumption.

that the eocological effects of increasing salmon aquaculture are highly debated (e.g., Naylor et al., 2001). Further consideration would have to be given to this debate if the decision tool were to also incorporate a weighing of the ecological impacts of food choices.

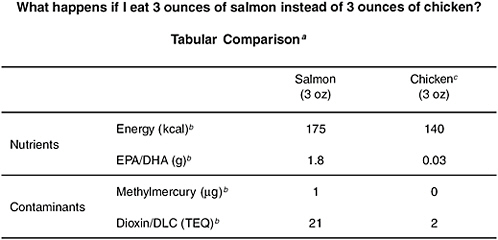

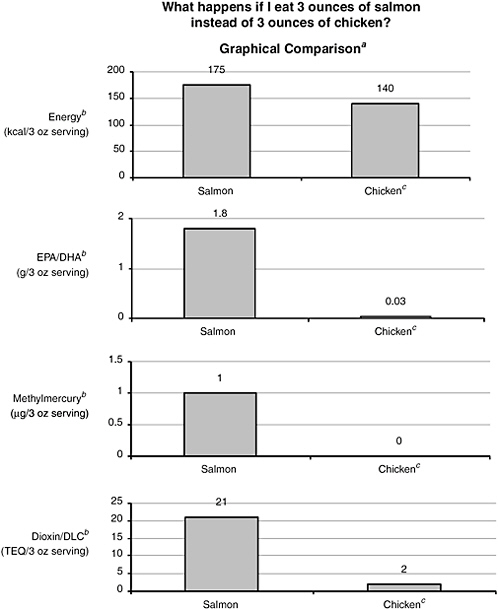

Another alternative format structure might be a comparison of two meal options, as illustrated in Figures 7-4a and 7-4b for the example of consuming a serving of salmon vs. a serving of chicken. Full development of this comparison approach would require information, such as that shown in Table 5-1, on a full range of seafood and other food products that consumers may substitute for each other.

Decision analyses can be presented in several formats (e.g., Figures 7-3, 7-4a, and 7-4b) or used to lead consumers through a decision pathway, for example, via an interactive Web-based program that graphically provides tailored information. In a Web-based format, the consumer could proceed by answering a set of questions such as those shown in Figure 7-1.

FIGURE 7-4a Example of a substitution question approach with tabular presentation of information—What happens if I eat seafood X (e.g., salmon) instead of food Y (e.g., chicken)?

aContinue the table with other nutrients/contaminants/other factors of interest.

bHot link the units to explanations and definition (for example, TEQ = sum of toxicity equivalency factors (TEF); where TEF is a numerical index that is used to compare the toxicity of different congeners and substances, in this case dioxin congeners.

cNote that EPA/DHA levels in chicken and eggs are based on existing published data; changes in the use of fishmeal in feed sources may have an impact on levels detected in the future.

The example decision pathway shown in Figure 7-2 distinguishes between consumer target populations in order to tailor consumption advice based on current evidence regarding the benefits and risks of seafood consumption. It also assumes that consumers agree with and accept the health goals and risk assessments implicit in federal nutritional guidelines and risk advisories.

Additional information can be added to explain branching in the decision pathway and the reasons for it. Designers will need to test the effects of presenting information on seafood choices in alternative formats. The first set of hypertext explanations would link the questions asked in the decision pathway to the research used to create the pathway, to explain the questions’ relevance to assessment of benefits and risks, and to provide consumers with links to more detailed information on the personal benefits and risks associated with seafood consumption. Table 7-1 shows examples of the types of explanations that might be used as added information in the

FIGURE 7-4b Example of a substitution question approach with graphical presentation of information—What happens if I eat seafood X (e.g., salmon) instead of food Y (e.g., chicken)?

aContinue the graphs with other nutrients/contaminants/other factors of interest.

bHot link the units to explanations and definitions (for example, TEQ = sum of toxicity equivalency factors (TEF); where TEF is a numerical index that is used to compare the toxicity of different congeners and substances, in this case dioxin congeners.

cNote that EPA/DHA levels in chicken and eggs are based on existing published data; changes in the use of fishmeal in feed sources may have an impact on levels detected in the future.

TABLE 7-1 Examples of Possible Additional Layers of Information to Provide to Interested Consumers

|

|

Possible Content of “Click Here for More Background Information” |

|

Age |

Children should eat age-appropriate portions. (hypertext link to table or pictures of age-appropriate portions) |

|

Gender |

Mercury accumulates in the body, and so can pose a risk to a nursing infant or future baby. This is why gender is important. |

|

Pregnant, could become pregnant, lactating |

Mercury accumulates in the body, and so can pose a risk to a nursing infant or future baby |

|

Prior cardiovascular event |

The evidence that suggests that those who have had heart attacks may reduce their risk by consuming EPA and DHA is weaker than previously thought. (link to additional data, source) |

|

Seafood type, source, and preparation method |

Explanatory paragraphs could summarize benefit and risk data for various species, by geographical origin (where data exist to distinguish in this way), and whether commercially available or self-caught fish. They could also discuss preparation methods—risks of raw fish (see Chapter 4) and cooking methods (e.g., frying, breading) that can abbrogate nutritional benefits. Current data do not support distinctions between seafood types beyond those made in the Food and Drug Administration/US Environmental Protection Agency 2004 advisory. |

|

Alternative sources of nutrients; benefits, risks, and costs of alternatives |

As addressed in Chapters 3, 4, and 5, other foods and fish-oil supplements are also sources of EPA and DHA. Other trade-offs identified in Chapter 5 could also be summarized for consumers. Regular updating would be necessary, given that changes in the use of fishmeal and other content in feed has changed and will change the nutritional value of animal products. |

formats. Designers will need to test the effects of presenting information on seafood choices in alternative formats.

Presenting Quantitative Benefit-Risk Information: The Promise and Peril of Visual Information

Both anecdotal and experimental evidence support the use of visual information as superior to either text or numbers in many contexts. The inclusion of alternative presentations of benefit-risk information in the design of consumer advice recognizes that while some consumers prefer to follow the advice given them by experts, others want to decide on the benefit-risk trade-offs for themselves. Consumers differ in their ability to interpret spe-

cific benefit or risk metrics. As discussed in Chapter 6, effectively informing decision-making requires the use of metrics that consumers can evaluate and use. A consumer-centered information design and evaluation approach is needed that makes information “easily available, accurate, and timely” (Hibbard and Peters, 2003). One approach is to present numerical information graphically (Hibbard et al., 2002). Consumers should be familiar with rating systems that represent benefits and risks in a small number of categories (often five), as is done for crash test ratings (TRB, 2002). The UK Food Standards Agency (FSA) has proposed “red-amber-green” multiple traffic light labeling for foods (FSA, 2005, 2006; http://www.food.gov.uk/foodlabelling/signposting/signpostlabelresearch/).

Graph comprehension depends on experience and expectations, as well as on the design of the graph in question (Shah and Hoeffner, 2002). Familiarity with an analog, as in the multiple traffic light system proposed by the FSA, can aid comprehension. Consumer testing carried out by Navigator for FSA (FSA, 2005) suggests that the multiple traffic light system helps consumers choose more nutritious foods, although the system has been criticized for its simplicity (Fletcher, 2006). Other common graphical approaches to presenting benefits or risks include “thermometers,” rank-ordered bar charts, or a more complex graphic embedded in a matrix of benefit and risk information, as is done by Consumer Reports.

While some of these approaches have been tested empirically, an agency developing consumer guidance should test prototypes on representative consumers. A potential problem in presenting benefit and risk metrics together is that the consumer may misinterpret the relationship between benefit and risk. For example, consumers are likely to infer that side-by-side thermometers or bars are directly comparable, even if they are labeled with different numerical scales.

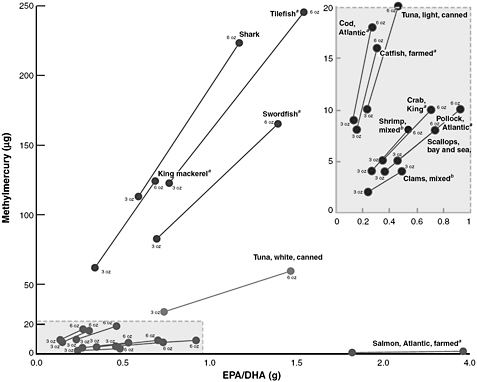

Formats such as those presented by the committee in Figures 7-2 through 7-4b can serve as suitable advice for consumers who want general guidance on seafood consumption. However, other consumers may want specific information for different seafood products. In Navigator’s testing, consumers preferred additional text to be informational rather than advisory (FSA, 2005). For these consumers, there is a large family of graphics that could be used to present choices across a broad range of seafood products. The committee developed several examples of graphical presentations of guidance to illustrate possible approaches. In presenting such graphics, the committee emphasizes its finding that it is not possible to have a single metric that captures complex benefit-risk relationships. Any sort of score system is unlikely to capture the inherent uncertainties in what is known about the underlying benefit-risk trade-offs. Graphical formats should be carefully and empirically tested to insure that they effectively communicate with consumers.

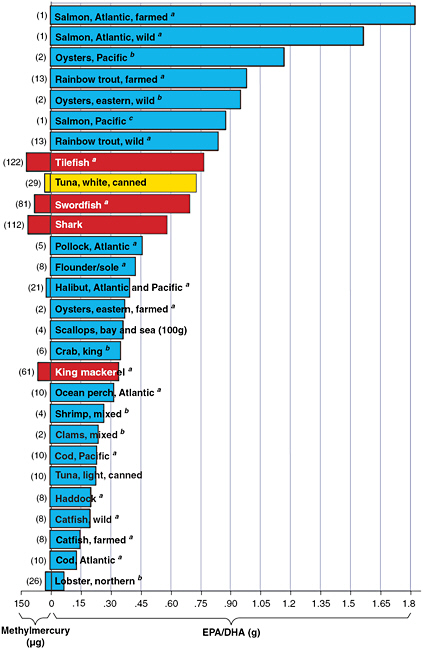

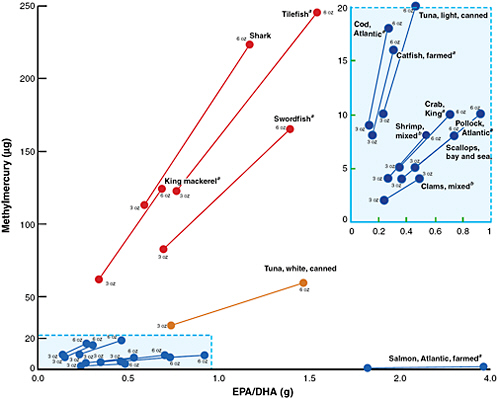

Multiple design decisions are required to produce graphical guidance; all could influence the impression the consumer takes away. These decisions include the selection of the seafood types to show; the colors, order, and formatting of bars to use; and whether to employ error bars to communicate uncertainty about point estimates. The graphical examples presented in Figures 7-5 through 7-8b below focus on information on EPA/DHA and methylmercury in seafood selections. A particularly important design choice here is the inclusion/exclusion and relative size of the scale of EPA/DHA bars as compared to the scale of methylmercury bars. Similar decisions would need to be made in presenting other benefit (e.g., low-fat profiles) and risk (e.g., other contaminants) information in these types of formats. In the figures presented here, the relative lengths of the EPA/DHA and methylmercury scales have been chosen arbitrarily, as the committee has not determined quantitatively the relative values of benefits from EPA/DHA and risks from methylmercury. The graphics present information that the consumer would use in conjunction with specific guidance that is appropriate for them (e.g., consumption of EPA/DHA, avoidance of methylmercury).

Figures 7-5 through 7-7 are examples of formats that could be tested with consumers. In the discussion here, the committee highlights considerations in the alternative approaches. All of these graphics relate to the benefit-risk tradeoff between EPA/DHA consumption and methylmercury intake. The use of this example reflects the fact that information is more complete here than for other nutrient and toxicant effects, not that these are the only benefit-risk tradeoffs that are relevant to consumers. However, the effect of graphics like these is likely to be to draw consumers’ attention to this information, and to ignore other possibly relevant information.

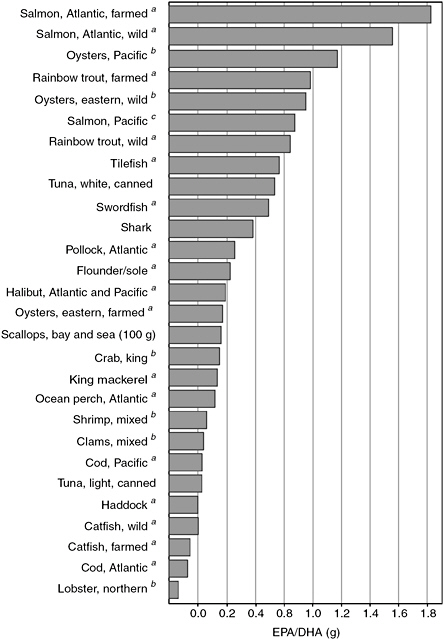

Figure 7-5 emphasizes the EPA/DHA content of different fish in grams per 3-ounce serving. This monochromatic graph is intended to emphasize benefits and provide guidance on seafood choices to enhance EPA/DHA consumption. This figure may be appropriate by itself for the guidance of adolescent males, adult males, and females who will not become pregant. For females who could become pregnant, are pregnant, or are lactating, and for infants and young children, the graph might include colored bars (red and yellow) to indicate fish (e.g., tilefish) containing levels of methylmercury that increase the potential for adverse health effects for these groups.

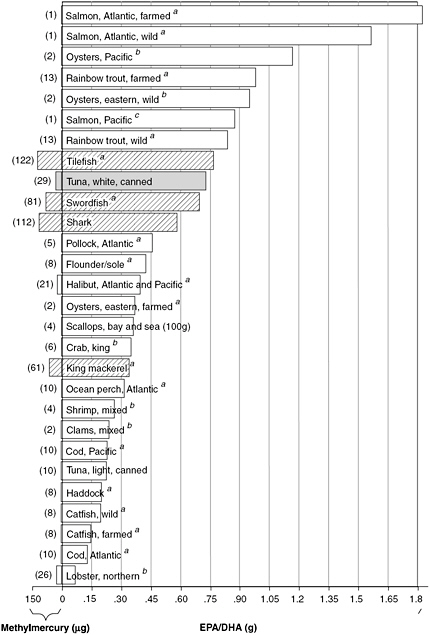

Figures 7-6a and 7-6b combine the presentation of information on EPA/DHA and methylmercury levels in a 3-ounce serving for different types of seafood. Two versions of this graph are presented in order to emphasize the design issues involved. These issues arise from the fact that the committee could not use a single scale, quantitative metric (e.g., Quality Adjusted Life Year, Disability Adjusted Life Year) for the combined benefit-risk profile of different seafoods. Thus, the information for methylmercury and EPA/DHA must be presented in separate metric scales that are not directly comparable.

FIGURE 7-5 Estimated EPA/DHA amount (grams [g]) in one 3-ounce portion of seafood.

NOTES: The scale used in this figure for EPA/DHA content is arbitrary. Designers will need to carefully test the effect of the scale used for the bars on the message received by consumers.

aCooked, dry heat.

bCooked, moist heat.

cThe EPA and DHA content in Pacific salmon is a composite from chum, coho, and sockeye.

FIGURE 7-6a Example of estimated EPA/DHA (grams [g]) and methylmercury (microgram [µg]) amounts in one 3-ounce portion of seafood.

NOTES: The scales used in this figure for EPA/DHA and methylmercury content are arbitrary. Designers will need to carefully test the effect of the scales used for the bars on the message received by consumers.

aCooked, dry heat.

bCooked, moist heat.

cThe EPA and DHA content in Pacific salmon is a composite from chum, coho, and sockeye.

FIGURE 7-6b Example of estimated EPA/DHA (grams [g]) and methylmercury (microgram [µg]) amounts in one 3-ounce portion of seafood, with emphasis on methylmercury.

NOTES: The scales used in this figure for EPA/DHA and methylmercury content are arbitrary. Designers will need to carefully test the effect of the scales used for the bars on the message received by consumers.

aCooked, dry heat.

bCooked, moist heat.

cThe EPA and DHA content in Pacific salmon is a composite from chum, coho, and sockeye.

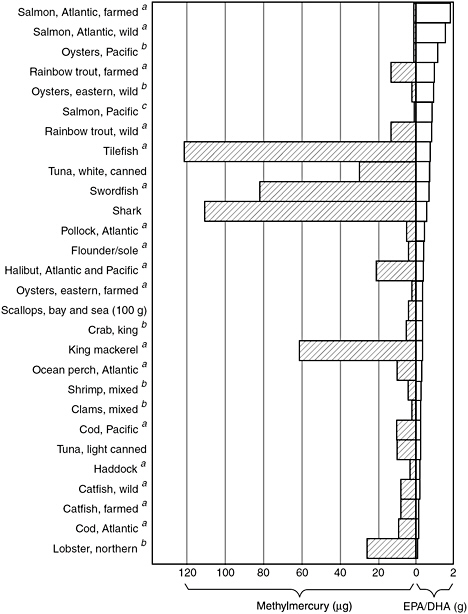

FIGURE 7-7 Estimated EPA/DHA (grams [g]) and methylmercury (micrograms [µg]) amounts in one and two 3-ounce servings perweek amounts.

NOTES: The scales used in this figure for EPA/DHA and methylmercury content are arbitrary. Designers will need to carefully test the effect of the scales used for the bars on the message received by consumers.

aCooked, dry heat.

bCooked, moist heat.

Figures 7-6a and 7-6b illustrate that the choice of scales to use for each can greatly affect the graph’s appearance. Testing with consumers is required to assess the impression made by alternative formats.

The scales used in Figure 7-6a have the effect of emphasizing information on EPA/DHA content and illustrate that there are a number of seafood choices, with varying levels of EPA and DHA, available with low exposure to methylmercury. The figure does not provide information about levels of lipophilic contaminants such as dioxins and PCBs because of the limited availability of data for various types of seafood. However, evidence presented in Chapter 4 suggests that levels of these contaminants in commercially obtained seafood do not pose a risk of adverse health effects even among the most at-risk groups, i.e., females who could become pregnant, are pregnant, or are lactating, and infants and young children, when consumed in the amount of two 3-ounce servings per week. As shown, Figure 7-6a may be appropriate for guidance to females who could become pregnant, are pregnant, or are lactating, and for infants and young children, as the shaded bars indicate types of seafood that should be avoided or consumed in limited amounts by individuals in these target populations. For adolescent males, adult males, and females who will not become pregnant, Figure 7-6a could be used for guidance without any specially shaded bars.

Figure 7-6b uses alternative scales to show the methylmercury and EPA/ DHA content in 3-ounce servings of different seafoods. The design tends to emphasize the methylmercury and deemphasize the EPA/DHA information. A side-by-side comparison of Figures 7-6a and 7-6b illustrates the impact of design choices on how consumer guidance information is presented. The committee again emphasizes that the scales used in Figures 7-6a and 7-6b for EPA/DHA and methylmercury content are arbitrary. Designers will need to carefully test the effect of the scales used for the bars on the message received by consumers.

Figure 7-7 also provides information on both EPA/DHA and methylmercury content, although for a smaller number of seafood choices to make the figure easier to read. The figure’s advantage is that it combines information on one and two 3-ounce servings per week. The corresponding disadvantage is that it may be harder for consumers to grasp. Graphs like this can be helpful in identifying product consumption patterns that provide benefits with little risk to most consumers as compared to those that raise risk concerns for some consumers. Figure 7-7 may be useful guidance for females who could become pregnant, are pregnant, or are lactating, and for infants and young children. If the EPA/DHA-methylmercury tradeoff is less important, for example, for adolescent males, adult males, and females who will not become pregant, then Figure 7-5, which focuses solely on EPA/DHA content, may provide more useful guidance. Here, the committee again notes that the choice of scale on the horizontal and vertical axes may

have an important effect on the message received by consumers. This effect should be carefully tested in the design phase.

Finally, Figures 7-8a and 7-8b illustrate the use of color to highlight information that is important to specific target populations. Figure 7-8a is a color version of Figure 7-6a. Seafood choices containing levels of methylmercury that exceed recommended safe intakes for females who could become pregnant, are pregnant, or are lactating, and for infants and young children and that should be avoided by these groups are shown in red. White (albacore) tuna is shown in yellow to indicate that consumption should be limited to 6 ounces per week for these at-risk population groups. Figure 7-8b, a color version of Figure 7-7, uses the same color scheme to emphasize choices for these groups.

The sample graphics presented here do not include a representation of uncertainty. Uncertainty can be represented with additional symbols (e.g., adding error bars), text or numbers, or with variations on the original graphic (e.g., by fading out the ends of the bars in a bar chart to indicate uncertain values or quantities. A consumer right-to-know perspective suggests that agencies are obligated to report or reveal uncertainties to interested consumers, and should strive to do so as transparently as possible. Representing uncertainty explicitly has the potential to improve decision-making (Roulston, 2006); failure to communicate uncertainty can increase public distrust (Frewer, 2004). However, testing is essential, as explicit representation of uncertainty can have unanticipated effects (Johnson and Slovic, 1995, 1998).

Given the weaknesses in the data underlying current conclusions on benefits and risks, strengthened collaboration between federal agencies appears to be an important goal for development of improved seafood consumption guidance. A federal advisory committee is one mechanism that could be used to coordinate across agencies.

In addition to collaboration between agencies, collaborating with nontraditional partners can assist federal agencies not only with dissemination of guidance, but with design and formative evaluation by engaging relevant target populations and providing a privileged relationship with them through the partnering organization. There are large networks of health care providers including but not limited to federal agencies that dispense daily advice on health and wellness and recommendations for medical care to broad segments of the population, including groups at high risk for poor health outcomes (SOURCE: http://www.healthfinder.gov). There are many opportunities to communicate benefit and risk information to at-risk population groups; a dramatic increase in immunization rates for children achieved in the mid-1990s illustrates one successful effort (CDC, 1996). A coordinated and tailored approach to individual consumer decision-making would have utility in working with federal agencies and other public health providers.

FIGURE 7-8a Color version of Figure 7-6a.

NOTES: The scales used in this figure for EPA/DHA and methylmercury content are arbitrary. Designers will need to carefully test the effect of the scales used for the bars on the message received by consumers.

aCooked, dry heat.

bCooked, moist heat.

cThe EPA and DHA content in Pacific salmon is a composite from chum, coho, and sockeye.

FIGURE 7-8b Color version of Figure 7-7.

NOTES: The scales used in this figure for EPA/DHA and methylmercury content are arbitrary. Designers will need to carefully test the effect of the scales used for the bars on the message received by consumers.

aCooked, dry heat.

bCooked, moist heat.

Communicating this information to these groups would often entail little or no increased cost. The limiting factor may be education of the providers (e.g., public health nurses) themselves. National associations could be an easy point of access for communicating information and networking (e.g., http://www.naccho.org).

Most state public health agencies, as well as many city and county agencies, have some statutory responsibility for seafood safety (advisories and posting regulatory actions, e.g., based on bacterial testing of oyster beds). Most of these agencies have health education programs including nutrition staff who provide individual counseling as well as health education to the general public. These agencies touch virtually every community and citizen in this country—there are more than 3000 local public health departments, not including county and state departments (SOURCE: http://www.naccho.org).

Community and migrant primary health care centers are funded through section 330 of the US Public Health Service Act and are charged with providing primary care and disease prevention services to low-income and other at-risk groups. Growth of their network has been a priority of the federal government, and the number of local sites exceeds 400, reaching millions of people daily (SOURCE: http://www.hrsa.gov). These centers are more often than not placed in communities at-risk. The community migrant health centers have also shown that when emphasis and training on disease prevention issues have been made a priority, disease (e.g., breast and cervical cancers) prevention interventions can actually exceed those provided to members of the general population who are not regarded as at risk. Community migrant health could be an important vehicle in helping consumers make informed seafood choices.

Collaborative Approaches: Federal Coordination and Communicating Health Messages Through Nontraditional Partners

There are a variety of federally funded but locally administered consumer education (e.g., Cooperative Extension System, see Box 7-1) and maternal-child health agencies (e.g., Title 5, Women, Infants, and Children Program [WIC], Head Start) that provide guidance and care to the general public, and to mothers and children. Although located in different agencies (e.g., WIC is administered through the US Department of Agriculture, Head Start is administered through the Administration for Children and Families [ACF]), these programs frequently serve either similar or the same populations. As with health partners in community health centers, they have a similar emphasis on health education and communication, and present significant opportunities for influencing consumer decision making.

|

BOX 7-1 Cooperative Extension The Cooperative Extension is another nationwide educational network that delivers information to people in their homes, workplaces, and communities. Each US state and territory has a state office at its land-grant university and a network of local or regional offices. Extension links the resources and expertise of nearly 3150 county extension offices, 107 land-grant colleges and universities, and the federal government. County offices are staffed by one or more experts who provide useful, practical, and research-based information through printed and media-based materials, Web-based information sites, the telephone, community programs, and not-for-credit classes. This system is an excellent resource for disseminating health information and correcting misinformation. |

The Need for Pretest and Post Hoc Evaluation

One of the challenges in supporting informed consumer choice is how governmental agencies communicate health benefits and risks to both the general population and to target populations. Previous attempts at communicating benefits and risks may have resulted in misinterpretation or misuse, including a reduction or total elimination of seafood consumption, by the intended audiences (Willows, 2005). Federal agencies should develop new and consumer-friendly tools to disseminate current and emerging information to the public. Developing effective tools requires formative evaluation, as well as an iterative approach to design.

Some individual communities have made substantial progress in understanding the effects of different modes of health communication and modifying the message to achieve the desired community and/or individual response. One such example is the Inuit community in Alaska, where communication of health risks from fish consumption previously resulted in changing patterns of food consumption from traditional foods to highly processed and often unhealthy alternative foods. Through the use of tailored messages and the involvement of the community throughout the entire process, a more effective message is now being provided to local communities.

Implementation: Embedding Consumer Advice Within a Larger Consumer Information Program

Consumers face challenging choices about seafood. Both the seafood

supply and the information about benefits and risks of consuming that seafood are changing rapidly. Fortunately, rapid advances in information and communication technologies now make it possible for agencies to distribute more up-to-date and detailed information, more widely, than ever before. Over 80 percent of US adults under age 40 use the Internet (Fox, 2005). This, however, does not negate the role of point-of-purchase information and the broader information context.

Further, there are communication structures in place within various federal agencies that are often duplicative and not effectively utilized. There is no functional mechanism in place for planning and implementing a new or evolving communication system that is synergistic and not duplicative. The committee is not aware of any significant efforts in place that would coordinate access to various programs within and between agencies and departments. There is potential for implementation of an effective system for communicating benefits and risks associated with consumption of seafood, but the means for implementation are not apparent. Achieving a coordinated and consistent approach that gives consumers information they can use and understand is likely to require some kind of coordinating mechanism, such as oversight by an interagency task force.

RECOMMENDATIONS

The committee offers the following general recommendations relevant to the design of seafood consumption advice.

Recommendation 1: The decision pathway the committee recommends, which illustrates its analysis of the current balance between benefits and risks associated with seafood consumption, should be used as a basis for developing consumer guidance tools for selecting seafood to obtain nutritional benefits balanced against exposure risks. Real-time, interactive decision tools, easily available to the public, could increase informed actions for a significant portion of the population, and help to inform important intermediaries, such as physicians.

Recommendation 2: The sponsor should work together with appropriate federal and state agencies concerned with public health to develop an interagency task force to coordinate data and communications on seafood consumption benefits, risks, and related issues such as fish stocks and seafood sources, and begin development of a communication program to help consumers make informed seafood consumption decisions. Empirical evaluation of consumers’ needs and the effectiveness of communications should be an integral part of the program.

Recommendation 3: Partnerships should be formed between federal agencies and community organizations. This effort should include targeting

and involvement of intermediaries, such as physicians, and use of interactive Internet communications, which have the potential to increase the usefulness and accuracy of seafood consumption communications.

REFERENCES

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 1996. National, state and urban area vaccination average levels among children ages 19–35 months—United States, April 1994–March 1995. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 45(7):145–150. [Online]. Available: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/PDF/wk/mm4507.pdf [accessed May 12, 2006].

CDC. 1999. Framework for program evaluation in public health. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report: Recommendations and Reports 48(11):1–40. [Online]. Available: http://www.phppo.cdc.gov/dls/pdf/mmwr/rr4811.pdf [accessed April 21, 2006].

CDC. [Online]. Available: http://www.cdc.gov [accessed May 12, 2006].

Fletcher A. 2006. Academic slams food labelling plans as ‘too simplistic.’ FoodNavigator.com, Europe. [Online]. Available: http://www.foodnavigator.com/news/ng.asp?id=66287-kellogg-weetabix-pepsico [accessed August 27, 2006].

FoodSafety.gov. 2005. Consumer Advice. [Online]. Available: http://www.foodsafety.gov/~fsg/fsgadvic.html [accessed April 21, 2006].

Fox S. 2005. Data Memo. Generations online. PEW/Internet. [Online]. Available: http://www.pewInternet.org/pdfs/PIP_Generations_Memo.pdf [accessed April 21, 2006].

Frewer L. 2004. The public and effective risk communication. Toxicology Letters 149(1–3): 391–397.

FSA (Food Standards Agency). 2005. Signpost Labelling: Creative Development of Concepts Research Report. UK: Food Standards Agency. [Online]. Available: http://www.food.gov.uk/multimedia/pdfs/signpostingnavigatorreport.pdf [accessed April 13, 2006].

FSA. 2006. Board Agrees Principles for Front of Pack Labelling. Press Release, March 9, 2006. Food Standards Agency. [Online]. Available: http://www.food.gov.uk/news/news-archive/2006/mar/signpostnewsmarch/ [accessed April 21, 2006].

Hibbard J, Peters E. 2003. Supporting informed consumer health care decisions: Data presentation approaches that facilitate the use of information in choice. Annual Review of Public Health 24:413–433.

Hibbard JH, Slovic P, Peters E, Finucane ML. 2002. Strategies for reporting health plan performance information to consumers: Evidence from controlled studies. Health Services Research 37(2):291–313.

HRSA (Health Resources and Services Administration). [Online]. Available: http://www.hrsa.gov [accessed May 12, 2006].

Johnson BB, Slovic P. 1995. Presenting uncertainty in health risk assessment: Initial studies of its effects on risk perception and trust. Risk Analysis 15(4):485–494.

Johnson BB, Slovic P. 1998. Lay views on uncertainty in environmental health risk assessments. Journal of Risk Research 1(4):261–279.

Mark MM, Henry GT, Julnes G, eds. 2000. Evaluation: An Integrated Framework for Understanding, Guiding, and Improving Policies and Programs. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, Inc.

NACCHO (National Association of County and City Health Officials). [Online]. Available: http://www.naccho.org [accessed May 12, 2006].

Naylor RL, Goldburg RJ, Primavera J, Kautsky N, Beveridge MCM, Clay J, Folke C, Lubchenco J, Mooney H, Troell M. 2001. Effects of aquaculture on world fish supplies. Issues in Ecology 8:1–12.

NCI (National Cancer Institute). 2003. Pink Book—Making Health Communication Programs Work. [Online]. Available: http://www.cancer.gov/pinkbook/ [accessed April 21, 2006].

NIH (National Institutes of Health). 2006. Health Information. [Online]. Available: http://health.nih.gov/ [accessed April 21, 2006].

Roulston MS. 2006. A laboratory study of the benefits of including uncertainty information in weather forecasts. Weather and Forecasting 21(1):116–122.

Ryan KE, DeStefano, eds. 2000. Evaluation as a Democratic Process: Promoting Inclusion, Dialogue, and Deliberation: New Directions for Evaluation. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, Inc.

Schriver KA. 1990. Evaluation Text Quality: The Continuum from Text-Focused to Reader-Focused Methods. Technical Report No. 41. Berkley, CA: National Center for the Study of Writing. [Online]. Available: http://www.writingproject.org/cs/nwpp/download/nwp_file/136/TR41.pdf?x-r=pcfile_d [accessed April 21, 2006].

Shah P, Hoeffner J. 2002. Review of graph comprehension research: Implications for instruction. Educational Psychology Review 14(1):47–69.

Spyridakis JH. 2000. Guidelines for authoring comprehensible web pages and evaluating their success. Technical Communication 47(3):301–310. [Online]. Available: http://www.uwtc.washington.edu/research/pubs/jspyridakis/Authoring_Comprehensible_Web_Pages.pdf [accessed April 21, 2006].

TRB (Transportation Research Board). 2002. An Assessment of the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration’s Rating System for Rollover Resistance. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

USDA. Healthfinder. [Online]. Available: http://www.healthfinder.gov [accessed May 12, 2006].

USPSTF (US Preventive Services Task Force). 2001–2004. Guide to Clinical Preventive Services, 2001–2004. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. [Online]. Available: http://www.ahrq.gov/clinic/gcpspu.htm [accessed April 21, 2006].

Willows ND. 2005. Determinants of healthy eating in Aboriginal peoples in Canada: The current state of knowledge and research gaps. Canadian Journal of Public Health 96(Supplement 3):S32–S36; S36–S41.