16

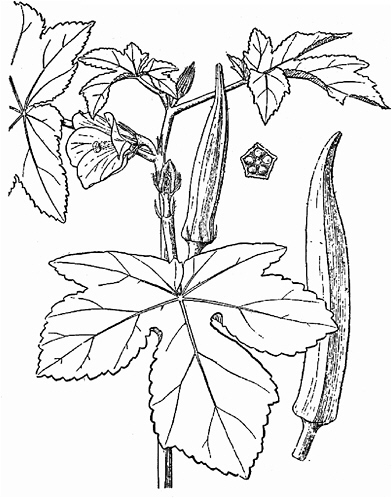

OKRA

Given the fact that it already grows almost everywhere in the tropical, subtropical, and warm temperate regions, okra would seem misplaced in a book on lost crops. Furthermore, only in a few locations has it developed into a major resource. Although perhaps a hundred nations know this African species first hand, none has raised it to anything like the heights attained by, say, cabbage, carrot, or common bean in the western world. For this there seems good reason: People generally don’t take to okra. In a 1974 survey made by the United States Department of Agriculture, for instance, adults named okra as one of the three vegetables they liked least, and children rated it with the four they liked second-least. 1

The sticky, mucilaginous juice inside the pods is the main objection. That slime blinds everyone to the plant’s greater potential. Of course, there are places where okra is regarded with something akin to reverence. Neither New Orleans nor West Africa, for instance, would be the same without it. But, given the crop’s overall status, most observers would logically conclude that okra’s natural limit as a global resource was reached long ago.

Seen in even broader perspective, however, that would be a suspect conclusion. In reality okra could have a future that will make people puzzle over why earlier generations failed to seize the opportunity before their eyes. In the Botanical Kingdom it may actually be a Cinderella, though still living on the hearth of neglect amid the ashes of scorn. Following are some reasons why it could soon rise and take a place alongside the royalty of crop plants.

This plant is perfect as a villager’s crop. For one thing it is easy to grow, robust, and little affected by pests and diseases. Also, it adapts to difficult conditions and can grow well where other food plants prove unreliable. For another, it provides good yields and possibly more products than any other vegetable. For a third, it is full of nutrients. And, economically speaking, its products are within almost everyone’s reach.

USDA Farmers Market, Washington, DC. Okra is an African market vegetable now found in cuisines as disparate as French and Japanese. It is common throughout South Asia and, of course, it is popular in Caribbean and African cooking. The word gumbo derives from a Bantu word—ki ngombo—for this vegetable. The size of a thick, long green bean, this vegetable is high in fiber and provides solid provitamin A and vitamin C, as well as minerals such as calcium, magnesium, and potassium. Okra can be boiled, blanched, fried, sauteed, and steamed and is even tasty when raw, young, and fresh. So why don’t we see more of it in supermarkets and on restaurant menus? (M.R. Dafforn)

For a food resource, the okra plant is strange; it is a coarse, upright herb bearing fuzzy green pods somewhat reminiscent of beans. Their mucilage may turn off newcomers, but many Africans, and a growing number of others, consider the slithery texture no deterrent—indeed, they see it as perhaps okra’s most desirable feature. A popular soup vegetable, very much appreciated in West Africa for its thickening power, okra pod is used both fresh and dried.2 Dry pods are also pounded into flour that is commonly added to foods. In the Sahel, this flour is also used in the final stages of preparing couscous, as it prevents the granules sticking to each other.

In America, where it appears almost exclusively in stews and soups, okra is usually seen in cross section, cut into disks that look like little cartwheels with a seed nestled between each pair of spokes. Okra is also the key ingredient in gumbo, the famous dish of the American South.

The plant is primarily employed, of course, as a vegetable; its pods, seeds, leaves, and shoots, as well as the outer cover of the flowers (calyx) are all eaten as boiled greens. But that is just the beginning. Okra seeds contain protein as well as oil possessing qualities like those of olive oil, the standard of excellence. And the seeds produce their protein and oil in goodly quantities. One experiment in Puerto Rico documented yields of 612 kg per hectare oil and 658 kg per hectare protein.3 Such quantities rival those of other oil-and-protein crops of both temperate and tropical zones.

Like soybean, the seed provides excellent vegetable protein for uses including full- and fat-free meals, flours, protein concentrates and isolates, cooking oils, lecithin, and nutraceuticals (foods with functional health benefits). Okra protein is both rich in tryptophan and adequate in the sulfur-containing amino acids, a rare combination that should give it exceptional power to reduce human malnutrition. In addition, byproducts such as hulls and fiber can be used for animal feeds.

Even the “slime” might be marketable. The plant could have a future in serving the booming markets for health foods. Given an aging global population increasingly concerned over sickness prevention, mucilage is big business these days. Gums and pectins of a type comprising nearly half of each okra pod are thought to help lower serum cholesterol in the bloodstream.4 Okra is also widely recommended as one dietary tool to help stabilize blood sugar in diabetics, because its high soluble fiber may cut the pace at which sugars are absorbed from the intestine.

The plant could have a future also as a supplier of commercial laxative ingredients. Its gelatinous substances absorb water, swell, and ensure the bulky stools that obviate and overcome constipation. Any and all dietary fiber is helpful but okra seems to rank with two crops now commanding multimillion-dollar markets: flaxseed and psyllium.5 In other words, this vegetable may not only bind excess cholesterol and toxins but assure their quick and easy passage out of the body.

The okra plant could also provide the world with mucilage for topical use. A similar polysaccharide gum comes from aloe vera, a traditional plant exploding in use because its products are believed to help heal wounds, soothe burns, minimize frostbite damage, and perhaps provide other medicinal benefits. Despite a lack of detailed evidence, there seems no reason why okra mucilage cannot play a part in supplying industries that

now employ aloe vera. Already it is the hidden ingredient that makes catsup so hard to get out of the bottle. Okra gum is also potentially useful as an extender of serum albumin and egg whites. It has even been used to size paper in Malaysia.

This versatile plant could also have a future producing top-of-the-line paper of the sort used to make fine documents and currency. In this case, the fibers on the outside of the stalk are used. Okra has “bast fiber” like that of its close cousin kenaf (Hibiscus cannabinus). Both these fast-growing, look-alike African cousins open the possibility of farmers joining foresters to fill the world’s insatiable demand for paper. In the United States, kenaf has already created a small industry. Kenaf is said to produce annually more paper per hectare than southern pine, the country’s most productive papermaking tree. And it is harvested every five months, rather than every 30 years, which eases market planning and makes for many other efficiencies. Moreover, kenaf paper is stronger, whiter, longer lasting, more resistant to yellowing, and has better ink adherence than pine-tree paper. Although it apparently hasn’t been tested yet, okra paper seems likely to be just as good.

Beyond all that, this plant could have a future also as a producer of various products used to soak up liquids. These special materials are made from the pith that remains after the stem fiber has been stripped away. In kenaf, this byproduct is proving suitable for animal bedding, for sopping up oil spills, for chicken and kitty litter, and for potting soil. It seems likely that okra’s counterparts would be comparable.

Based on the rising experiences with its country cousin, okra could, at least in principle, have a future producing yet more things that are strange for a vegetable crop, including:

-

Construction materials. (Kenaf-blend panels are said to perform better than the present particleboard.)

-

Handicrafts. (Kenaf fiber makes excellent mats, hats, baskets, and more.)

-

Forage. (Chopping up the whole kenaf plant and feeding it to animals has proven successful.)

-

Fuel. (Kenaf roots and stems of burn fiercely.)

In sum, this African resource could be a tool for improving nutrition, rural life, rural development, foreign exchange, and much more.

PROSPECTS

Seen in light of the above information, okra might have a grand future as an industrial crop. And there seems to be little difficulty in producing the

Berekum market, Dormaa District, Brong Ahafo Region, Ghana. A perfect villager’s vegetable, okra is robust, productive, fast growing, seldom felled by pests and diseases, and high yielding. It adapts to difficult conditions and can thrive where other food plants prove unreliable. Among its useful food products are pods, leaves, and seeds. Among its useful non-food products are mucilage, industrial fiber, and medicinals. Seen in overall perspective, this often-derided resource could be a tool for improving many facets of rural life. (Nigel Poole)

plant on a large scale. In the United States, for example, some is already produced in quantities big enough for the pods to be canned, frozen, or brined for the nation’s supermarkets. As a fresh vegetable the crop’s prospects are more enigmatic, but positive for all that. As with avocado or whisky, the palate’s initial resistance usually mellows with greater exposure. But at core, it is an African vegetable whose greatest beneficence may well lie with its people.

Within Africa

Humid Areas Excellent. Fast-maturing types are well suited to tropical heat and humidity.

Dry Areas Excellent. Although not structurally adapted to growing under desert conditions, the plant shows remarkable tolerance to drought and heat and can generally perform reliably in Africa’s savanna regions.

Upland Areas Excellent. With a crop as adaptable as this, there should be no trouble finding varieties to fit into localities up to about 1,000 m in elevation that have a reasonable growing season.

Beyond Africa

Okra is clearly not restricted to Africa. Indeed, it performs exceptionally well elsewhere. In South Asia as well as in tropical America, China, and perhaps Australia and the United States, it might well become a new agroindustrial resource.

USES

Everything part of this plant seems to offer some useful purpose or other.

Pods In their immature form the pods are the plant’s main edible portion. Although mainly employed as a boiled vegetable, they can be stir-fried, battered and deep-fat fried, microwaved, steamed, baked, and grilled. Some are blanched and processed as a frozen (plain or breaded), pickled, or canned product.

Whether boiled, added to soups, or sliced and fried, the pods have a unique flavor and texture. They may be used alone or mixed with other vegetables. Mucilage released when okra slices are fried is known to be a good thickening agent for gravy. In West Africa, young pods are thinly sliced to prepare okra soup, which has been called “a perfect partner with fufu” (the region’s main staple, made of starchy roots).

Inside the dried pods the gums stay intact and remain useful for flavoring and thickening foods. West Africans slice, sun dry, and grind pods into a powder that is put away for the hungry time that hits each year just before the new harvest. In Turkey the pods are strung out to dry for winter use.

Seeds Typically, the seeds are obtained from pods that become too mature to be eaten fresh. The cooked pods can also be squeezed to expel the seeds. Those seeds are commonly used in place of dried peas or beans or lentils in soups or in other dishes, including rice.

Coffee Substitute Mature dried seeds can be roasted and ground as a coffee substitute. This was once widely used in places like El Salvador and other Central American nations, Africa, and Malaysia. According to one report “the resulting ‘coffee’ has a good aroma and is inoffensive, since it lacks the stimulating effect of caffeine.” A prominent book on African wild foods calls okra “one of the best coffee substitutes known.”

Oil and Protein Okra seed’s potential as a source of oil and protein has been known since at least 1920. About 40 percent of the seed kernel is oil.

This greenish-yellow liquid has a pleasant odor and a high (70 percent) content of unsaturated fatty acids, especially linoleic and oleic. It has a short shelf life but is readily hydrogenated and could be used to make margarine or shortening.

The residue left after oil extraction is a possible feedstuff. It contains over 40 percent protein as well as relatively high amounts of thiamin, niacin, and tocopherol. But some lingering questions of possible toxicity remain to be answered (see later).

Curd A research team in Puerto Rico has surprisingly found that okra can be turned into “tofu.”6 Led by Franklin Martin, the experimenters ground the seeds finely in water, strained the aqueous mixture through a cloth filter, and precipitated the protein by adding bivalent salts (such as magnesium sulfate) or acid (vinegar or lime juice). A taste panel found okra-tofu pleasant to eat fresh or cooked or as a cheese substitute. The protein and oil contents were as high as 43 and 53 percent, respectively.7

Leaves In areas where a wide variety of leaves are eaten (notably West Africa and Southeast Asia) tender okra leaves are often part of the daily diet. They are most frequently cooked like spinach or added to soups and stews. Some okra varieties have hairy leaves, an objectionable feature reduced by cooking; others are hairless. In West Africa the tender shoots, flower buds, and calyces are traditionally thrown into the pot as well. As with the pods, okra leaves are frequently dried in the sun, crushed, or ground to a powder, and stored for future use. In taste, they are somewhat acidic. By carefully picking lower parts of the plant it is possible to get a good crop of leaves without reducing the number of seedpods further up the stem.

Biomass At the end of the harvest season, the remaining foliage and stems can weigh 27 tons per hectare. This is quite burnable. The stems generate considerable heat but no sparks, excessive smoke, or bad smell. On the other hand, these light stems burn only briefly and to be useful may need a special stove. With fuel costs rising worldwide and new technologies promising efficient conversion to liquid fuels, okra biomass seems likely to become notably useful, especially as more tropical forests are destroyed.

Mucilage Obtaining the mucilage is simple. Slices of the immature pod are merely placed in water. Boiling thickens the mix. The mucilage is actually an acidic polysaccharide composed of galacturonic acid, rhamnose, and glucose. It achieves maximum viscosity at neutral pH, and tends to break down when overheated.

|

6 |

Martin, F.W. and R.M. Ruberte. 1979. Edible Leaves of the Tropics. Antillan College Press, Mayaguez. (3rd Edition, 1998, available via ECHONet.org.) |

|

7 |

The percentages were measured on a dry-weight basis. |

Ornamental Okra is closely related to the common ornamentals known as flowering hibiscus, making okra’s large and attractive blossoms seem somehow familiar (although they are yellow and sometimes come with a crimson center). The pods also have an interesting shape, and those that become too hard to eat can be dried, cured, and felicitously slipped into everlasting flower arrangements.

Medicinal Use People in the East have long used the leaves and immature fruit in poultices to relieve pain.

NUTRITION

Okra is more a diet food than staple. Pods are low in calories (scarcely 20 per 100 g cooked), practically no fat, and high in fiber. It does provide several valuable nutrients, including about 30 percent of recommended levels of vitamin C (16-20 mg), 10-20 percent folate (46-88 µg), and a little more than 5 percent vitamin A (14-20 RAE).

The leaves provide protein, calcium, iron, and vitamins A and C. No toxic substances have been reported in the leaves.

As noted earlier, the seeds are potentially a good source of an especially nutritious protein. In screening a large collection of seeds in Puerto Rico, it was found that their protein contents varied from 18-27 percent.8 The protein’s amino-acid profile differed from that of either legumes or cereal grains.9 It was rich in tryptophan (94 mg/g N) and had an adequate content of sulfur-containing amino acids (189 mg/g N). This okra protein thus complements, balances, and fulfills that of cereal grains and legumes, not to mention root crops. One advantage to processing okra seed is its simplicity. A hand mill and sieves were all it took to separate a high protein (33 percent), high oil (32 percent) meal from the hull.10

HORTICULTURE

Today, almost all okra is interplanted with other crops in small farms, in backyard gardens, and sometimes in truck farms established on the fringes of cities. Only in a few places is it grown alone on large commercial fields. Most is direct seeded. Owing to the thick seedcoat, the seed is first soaked overnight to improve germination. Seedlings can also be transplanted from a

nursery. Warm temperatures are needed both for good germination and good growth. Okra is similar to cotton in its temperature requirements. Commercial okra in the United States is planted at a population of 20,000-30,000 plants per hectare.

The crop is relatively free from pests and requires only minimal maintenance. However, in the southern United States, it can be subject to Verticillium and Fusarium wilts, and aphids, corn earworm, and stinkbugs can be major insect pests.

HARVESTING AND HANDLING

Flowering begins about 2 months after planting. Each flower then develops rapidly into a pod, which is typically harvested just 3-6 days after the flower formed. Pods harvested at this stage are tender, flavorful, and about half grown. Any that remain on the plant quickly turn fibrous and tough.

With proper field management, continuous flowering and high production can be maintained. Yields approaching 500 kg per picking per hectare (0.5 kg per plant) may be produced during a harvest period of 30-40 days. Okra is usually harvested at least three times a week. The pods have a high respiration rate and should be cooled quickly. Those in good condition will keep satisfactorily for 7 to 10 days at 7 to 10°C. A relative humidity of 90 to 95 percent helps prevent shriveling.

LIMITATIONS

The most important step in any vegetable-okra operation is harvesting the pods correctly and regularly picking the pods every few days. That induces more production and greatly increases yield.

Fresh okra pods bruise easily, blackening within a few hours. A bleaching type of injury may also develop when they are held for more than 24 hours without cooling.

Some okra plants and pods have small spines to which some people are allergic. Picking the crop can produce itchy arms.

NEXT STEPS

Of all the earth’s useful plants this is one of the most misunderstood. Taken all round, it likely offers as many production possibilities as ever dreamed in a single plant. However, it also is stuck in a mental warp. Although it holds enough potential to keep a dozen researchers productive for their lifetimes, few are seriously developing it at present.

Industrial Development

With such an array of possibilities, several rural industries might be built around this species, much as around bamboo or rattan in eastern Asia. Okra

thus offers a possible route to prosperity for both small-scale and large-scale producers in numerous nations. Here are some options.

Oilseed No one knows the future okra could have as an oilseed, but at least at first sight it could be quite big. The oil is easily extracted using either solvent or mechanical press. Both the greenish-yellow color and the not unpleasant odor are easily removed. Machinery for harvesting the seed has been developed and to extract the oil machinery designed for cottonseed can be employed.

Needed now is a major follow-up to the work in Puerto Rico, which has been overlooked since it was published decades ago.11 This should start with test plantings large enough to yield samples of okra seed oil and protein for modern evaluation by chemists, food technologists, and industries that purchase vegetable oils and proteins. It’s a big undertaking, considering that okra oil and okra seed protein have never been produced in quantity before, but it could open the door to a new agroindustry for the warmer regions of the world.

Mucilage On the surface, there seems no reason why okra mucilage cannot play a part in supplying industries that now employ psyllium, flaxseed, and aloe vera. However, confirmation is needed. Issues needing clarification include the performance of okra product, safety, and likely price range. Again, growers or researchers should produce enough for evaluation by chemists, food technologists, and companies that buy mucilaginous materials. Again, it could open up the possibilities to vast new industries for many lands.

Paper Pulp Any reader who already grows okra may by now be wondering if we really know the plant. But that is only because the types grown for vegetable purposes are specially bred dwarfs, typically less than a meter in height and surely inappropriate for papermaking or fuel or particleboard. However, among this species’ huge biodiversity are African varieties with stems towering 5 m and “trunks” like small trees (up to 10 cm diameter). At least in principle, those can be harvested for pods, seeds, and leaves and later felled for fiber or fuel. Some varieties even show a perennial nature. This multi-year production—like the ratooning used with sugarcane—saves the expense, trouble, and delay that comes with making a second planting.12

In the temperate-zone summer most of these tall, robust, West African okras bloom too late to set seed. Instead, they devote their considerable energy to vegetative growth. Far surpassing garden varieties in the

production of fiber and biomass, they have the potential to revitalize okra breeding and okra as a global resource.

These tall types should be obtained and put into worldwide trials. Some trials should involve side-by-side comparisons with kenaf.

Bioabsorbents Pith, as we’ve said, comprises a major part of the stem. In kenaf it is proving suitable for animal bedding, oil-absorbents, chicken litter, kitty litter, and potting soil. Okra pith samples should be gathered and compared with kenaf’s. For these purposes, the two crops are less in competition than in cohoots. They can undoubtedly be marketed together and perhaps even mixed, thereby building a bigger, broader, and safer base of supply. Demand for bioabsorbents like these is likely to soar, both for the needs of environmental health and public health around the globe.

Horticultural Development Although there has been considerable selection and breeding of okra, it has emphasized the production of immature pods. The rest of the fantastic genetic diversity within this species is basically untapped, or even unexplored. That situation should be changed, and fast. Germplasm needs to be gathered up not only in Africa but also in Asia and other regions that know the crop.

With this genetic variability in hand, the way should be open for improving the compositional value of the crop for the various separate products. Varieties could be bred, for instance, for fiber, biomass, oil, protein, mucilage (type and yield), color, and ornamental use. Breeding studies could also be expanded to include improving yields, cultivation conditions, nutritional value, and nutraceuticals.

Okra flowers are structured for insect-pollination (bees, wasps, flies, and beetles, and perhaps even occasional birds), but self-pollination usually occurs and both hand-pollination and seed handling are straightforward. Controlled breeding is thus not difficult, although success in bringing out some characteristics may require very large populations and very careful evaluation.

Toxicity Checks Although both okra tofu and the protein-rich residue left after oil extraction offer promising foods and feeds, there is a possible drawback. Okra seeds, like cottonseeds, purportedly contain gossypol or a gossypol-like compound.13 All doubts will have to be removed before okraseed can be employed as a protein source. Strangely, should gossypol be present in commercial amounts it might possibly be used for the long-sought male contraceptive (see sidebar).

In at least some okraseed varieties the oil contains small quantities of cyclopropenoid fatty acids. These unstable compounds have strong

physiological effects and in hens are believed to suppress egg laying. However, the fact that some okra plants had only low quantities (the overall range was 0.26-5.59 percent) suggests that the problem might be bred out. These unusual fatty acids are easily removed by heating the oil during processing, but having none to start with would surely be better.

Basic Studies There are undoubtedly many fascinating physiologic and genetic features of the plant to investigate. Here are three that come to mind:

-

Ploidy Okra has a high number of chromosomes (2n=130) and behaves in some instances as a diploid and in others as a tetraploid. It is thought that one genome possibly comes from Abelmoschus tuberculatus (2n=58). Modern techniques could likely go far in sorting out okra’s genetic background and chromosome make up.

-

Hybridization Crossings within the species as well as possible hybrids with okra’s close, interesting, and useful relatives ambrette (Abelmoschus moschatus), kenaf, and roselle (Hibiscus sabdariffa) could provide fascinating plants with exceptional properties.

-

Okra’s origin Many publications still give the species’ origin as India, but that seems more current usage than scientific assessment. The vast occurrence of primitive types and wild relatives in Africa (especially Ethiopia) indicates okra is almost certainly African, but the lingering doubt should be put to rest by groundwork and DNA testing.

Food Technology

Here, too, are possibilities for fascinating research. Examples include:

-

Okra Tea Okra’s close cousin roselle has been making a name for itself in recent years as a major ingredient in non-caffeinated teas (notably in the United States, where it stars in the popular Red Zinger Tea®). Jamaicans know this okra relative as sorrel and consider it one of the island’s great delicacies, turning it not only into cooling beverages but into famous tarts and jellies as well. It is also a common tea in the Sahel, where it was introduced to provide plant fiber and vitamin C, and has now naturalized. Okras with red calyxes are known and should be tested for the possibility of producing a counterpart.

-

Decaffeinated Coffee Could okra seed be a direct route to a really good caffeine-free beverage? That is something for which a market seems more promising now than ever before, and the possibility deserves at least a look-see.

-

Gum-Free Okra Needed also is a simple test for mucilage content that would allow the germplasm to be screened. Then, pods of known polysaccharide content could be bred. Anyone creating gum-free okra will have given the world a major new crop. Of course, anyone creating

-

exceptionally gum-rich okra will also give the world a major new crop.

Progress and Public Relations In spite of the fact that okra is a potentially very important plant, little effort is being given to its development. As noted, this is largely due to the public’s negative mindset. To overcome popular repugnance requires more than science…it requires publicity. Some sort of Okra Appreciation Society would help give the vegetable a good push. It might foster newspaper and magazine coverage of okra’s possibilities. And it might operate such things as contests, recipes, home-economics courses, and nutritional awareness demonstrations. Although the plant’s prospects are high, its future depends on a mental course change to break it out of the slime still blinding everyone to the crop’s greater potential.

SPECIES INFORMATION

Botanical Name Abelmoschus esculentus (L.) Moench

Synonym Hibiscus esculentus L.

Family Malvaceae

Common Names

Arabic: bamia, bamya, bamieh

English: okro, lady’s finger, ladies finger, gumbo

India: bhindi, bindi, dheras, bandakai, vendakai

Chinese: ka fei huang kui, huang su kui, huang qiu kui, qiu kui (medicinal name); chan qie, ch’aan k’e, Ts’au kw’ai (Cantonese)

French: gombo, bamie-okra, ketmie comestible, ambrette

German: ocker

Spanish: gombo, ají turco, quimbombo, ocra

Portuguese: gumbro, quingombo, quiabo, quillobo

Akan (Twi): nkruman, nkruma (okra)

Bantu: ki ngombo, ngumbo, gombo

Congo, Angola: quillobo, ki ngombo

Swahili: gumbo

Thai: krachiap khieo, krachiap mon, bakhua mun

Greek: bamia

Hebrew: bamiya, hibiscus ne’echal

Hungarian: gombó, bámia

Italian: gombo, ocra, bammia d’egitto, corna di greci

Japanese: okura, Amerika neri, kiku kimo

Malaysia: bendi, kacang bendi, kacang lender, sayur bendi , kacang lendir , kachang bendi

Indonesia: kopi arab.

Description

Okra is an annual herb typically reaching 2 m in height, but some African varieties may grow up to 5 m tall, with a base stem of 10 cm in diameter.

The heart-shaped, lobed leaves have long stems and are attached to the thick woody stem. They may reach 30 cm in length and are generally hairy. Flowers are borne singly in the leaf axils and are usually yellow with a dark red or purple base. Some African varieties are photoperiod sensitive and bloom only in the late fall in temperate zones. It is largely to wholly self-pollinated, though some out-crossing is reported and it is often visited by bees.

The pod (capsule, or fruit) is 10-25 centimeters long (shorter in the dwarf varieties). Generally, it is ribbed or round, and varying in color from yellow to red to green. It is pointed at the apex, hairy at the base, and tapered toward the tip. It contains numerous oval seeds that are about the size of peppercorns, white when immature and dark green to gray-black when mature.

Distribution

The plant is immensely adaptable and is widely distributed in the tropics, subtropics, and warmer temperate zones. In essence, it grows almost everywhere anyone tries to plant it.

Within Africa Of all the native food crops, this is one of the most widespread within the continent. It is known from Mauritania to Mauritius, with most diversity centered around Ethiopia and the Sudan.

Beyond Africa It is now grown throughout southern Europe, Australasia, tropical Asia and America, the Caribbean, and the United States, where it is best known in the southern region but is also cultivated in Oregon and California. Turkey grows okra on a large scale.

Horticultural Varieties

Many cultivars have been selected for local conditions but in the main there are two types: the long and the short (quickly flowering) duration. The cultivars vary in plant height and in shape and color of the pod. With all the different cultivars and their variations, the particular kind of okra planted usually reflects what the local people prefer their dinner dishes to look like.

Although okra prefers a long, hot growing season, cultivars have been developed that are short in stature as well as fast maturing, and small fruited. These dwarf, short-duration types reach a height of 60 cm and require only 7 to 9 weeks to mature.

The okra seen in the temperate zones is fairly uniform. One survey of

266 temperate-zone varieties found no consistent differences. But that is misleading; this species encompasses huge genetic diversity that not even okra specialists have ever seen—it just hasn’t been distributed in the temperate zones.

Environmental Requirements

Okra is a warm-season annual well-adapted to many soils and climates.

Rainfall The plant tolerates a wide variation in rainfall.

Altitude Most selections are adapted to the lowland humid tropics, ranging up to at least 1,000m.

Low Temperature Minimum soil temperature for germination is 16°C. For good growth, night temperatures should not fall below 13°C.

High Temperature An average temperature of 20-30°C is appropriate for growth, flowering, and pod development. Most cultivars are adapted to consistently high temperatures.

Soil A range of soil types give good economic yields but (not unexpectedly) well-drained, fertile substrates with adequate organic material and reserves of the major elements are ideal. Some cultivars are sensitive to excessive soil moisture, so well-drained, sandy locations are preferred. Neutral to slightly alkaline conditions, pH 6.5-7.5, seem best.

Related Species

The genus Abelmoschus includes from 6 to 15 species in the Afro-Asian tropics and North Australia. One that stands out is abelmosk or ambrette (Abelmoschus moschatus Medik.; syn. Hibiscus abelmoschus). Indigenous to India and cultivated (or weedy) in most warm regions of the globe, it is a low, slightly woody plant with a conical five-ridged pod containing numerous brown kidney-shaped seeds that are smaller than okra’s. The seeds possess a musky odor and perfumers know them as ambrette (“abelmoschus” is from the Arabic “father of musk”, with “moschatus” also referring to a musky smell). The plant also yields an excellent fiber and, rich in mucilage, is employed in upper India for clarifying sugar. One variety there known as bendi-kai is eaten fresh, prepared like asparagus, or pickled. The foliage and tubers of A.m. subsp. tuberosus have been consumed for centuries in Australia.