1

AMARANTH

To the world of science, vegetable amaranths verge on the invisible. As far as international statistics are concerned, this crop doesn’t exist. Books highlighting world food plants, even those dealing specifically with vegetables, largely ignore it or accord only the briefest mention. Not surprisingly, then, researchers engaged in improving global food supplies pay little heed. Indeed, most may have never heard of a vegetable amaranth.

Yet if this leaf crop seems invisible, it is only because it is hidden in plain sight. At least fifty tropical countries grow vegetable amaranths, and in quantities that are far from small. Throughout the humid lowlands of Africa and Asia, for instance, these are arguably the most widely eaten boiled greens. During the production season, amaranth leaves provide some African societies with as much as 25 percent of their daily protein. In parts of West Africa the tender young seedlings are pulled up by the roots and sold in town markets by the thousands of tons annually. Other parts of the continent also rely on them to a similar degree. A definitive review of southern Africa’s native foods, for example, clearly lays out their status: “Of all the wild edible plants eaten in southern Africa, few if any are as well known and widely used as amaranths.”1

Amaranths are a poor people’s resource, and the plants are often dismissed as “lowly” and ignored as if, like poverty itself, they should be avoided at all costs. As a United States Department of Agriculture bulletin points out, few species of vegetables are so looked down upon. Several languages include the demeaning phrase “not worth an amaranth.” Indeed, the plants are sometimes regarded as being fit only for pigs (“pigweed” is the common name for one despised American species).

At first sight, this scorn seems almost universal. Amaranthus is one of the few genera whose species were domesticated in both the Old and New World.2 It has provided very ancient potherbs (boiled greens) not only to Africa but to Asia and the Americas as well. Nowadays the various species from the different tropical regions are pretty much scrambled up genetically, so that the origins of any given amaranth plant remain (at least for the

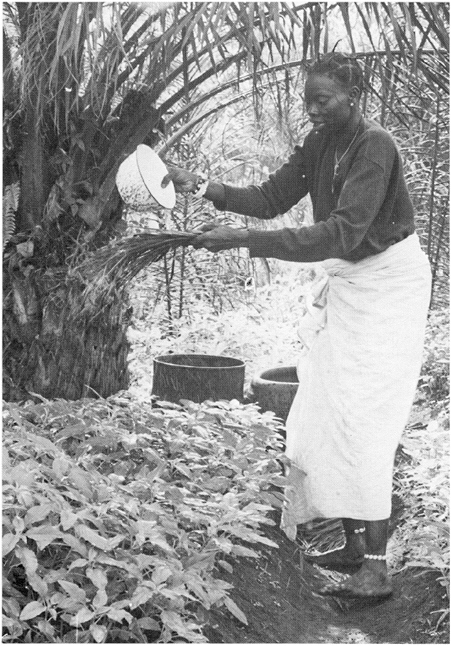

Vegetable amaranths are probably the most widely eaten boiled greens throughout Africa’s humid lowlands. They secure the food supply for millions. The leaves and stems make excellent boiled vegetables with soft texture, mild flavor, and no trace of bitterness. (Jim Rakocy)

moment) fuzzy.3 This seems to be especially the case in Africa.

Amaranth leaves and stems make boiled vegetables with soft texture, mild flavor, and no trace of bitterness. In taste tests at the U.S. Department of Agriculture in Beltsville, Maryland, most of the 60 participants said that cooked amaranth leaves tasted at least as good as spinach. Some likened the taste to that of artichoke.

Given the food-production experts’ lack of interest, one might imagine these plants to be difficult to grow and unappealing to the growers. But such is not the case. Amaranths produce seeds aplenty and their seedlings emerge so rapidly and sprout with such vigor that the first crop of leaves is sometimes harvested within three weeks of planting. Furthermore, new generations of leaves keep materializing, so that many harvests can be made before replanting becomes necessary. This aptitude for extended production not only eases the farmer’s burden, it leads to huge yields: one test produced 10 tons of edible greens per hectare in a 30-40 day harvest period.

Given their general lack of recognition, one might imagine these lowly

plants to lack nutritional power. Actually, they have high food value. The leaves have an exceptional protein quality, (25 percent for Amaranthus cruentus) reportedly containing more lysine (about 0.8 percent for A. cruentus)] than quality-protein maize (high-lysine corn) and more methionine than soybean meal. In addition, vitamins A and C occur in good quantities. Minerals such as calcium and iron are also present in abundance.

Given their lack of recognition one might imagine these lowly plants to possess such strict climatic and soil requirements that they grow well only in limited locations. Once more, however, the truth is quite the reverse. Amaranths demonstrate exceptional vitality in many types of sites. Most are pioneer species, whose niche in nature is the quick colonization of disturbed land. They therefore produce a huge number of fast germinating seeds and this may be why a classically minded botanist named them amaranth, an Ancient Greek word meaning “life everlasting.”4 The plants use the C4 photosynthetic mechanism, common in arid-land species, which enables them to thrive not only in hot weather but in dry weather as well.

Although in most of the lowland tropics the upper crust may hold vegetable amaranths in low esteem, in Caribbean nations the whole society honors these plants. The humble leaves are important ingredients in Caribbean cooking, especially in the famous regional favorite known as callaloo,5 which is normally a gumbo-like stew or a spinach-like vegetable dish that often features the texture of Africa’s okra (see Chapter 16). Callaloo is so central to the diet that it has become almost synonymous with the Caribbean image. The word has entered everyday talk as a word denoting the unique blending of food, language, music, and peoples constituting Creole culture. The name callaloo is appended to restaurants, magazines, shows, songs, bands, books, and more. It is an appellation bestowed with pride.

In China and Southeast Asia, a region renowned for quality vegetables, one amaranth—Chinese spinach, Amaranthus tricolor—ranks among the very best. Farmers in Hong Kong, for example, grow at least six types: pointed leaved, round leaved, red leaved, white leaved, green leaved, and horse’s teeth. Those in Taiwan grow a type called tiger leaf, which has green leaves with a red stripe down the center.6 They’re not only very pretty, they’re very tasty.

The fact that vegetable amaranths aren’t honored like this everywhere is a shame. These classic poor-people’s plants provide a perfect botanical tool

for helping the most nutritionally challenged strata of society. Taken all round, they represent a sort of do-it-yourself kit to good nutrition and lend themselves ideally to subsistence conditions. With them, little horticultural experience is needed before the benefits of better nutrition can be enjoyed. Although insect pests and diseases can be problematic, few if any tropical vegetables are easier to grow. In favorable locations amaranths produce food almost without attention.

Seen in overall perspective, these fighters offer frontline armaments in the battle to feed properly a malnourished world. They yield protein and other nutrients efficiently. They afford abundant provitamin A (beta-carotene), a nutrient vital to the millions of malnourished children now at risk of blindness. And they do it quickly.

In summary, amaranths are an important market vegetable for many farmers, but their main benefits are humanitarian ones. Without these humble plants, the hidden hunger of malnutrition would be much worse. With them in greater use, it can be greatly lessened.

PROSPECTS

Although vegetable amaranths have yet to catch the attention of most researchers and scientific establishments, few crops can match them for effectiveness in nutritional interventions. In places such as Africa they offer an easy entree intervention because they are even now consumed by, admired by, and sought by the rural peoples for whom food insecurity is a daily peril.

Within Africa

Humid Areas Excellent. Amaranthus species are of course already used widely as potherbs in the humid lowland tropics. Over the years, growers have selected types with leaves and stems of high palatability. The mild taste, high yields, high nutritive value, and ability to withstand hot climates make them popular. In flavor, food value, and “farmability,” they are the best of all tropical potherbs.

Dry Areas Modest. Given their C4 photosynthesis, amaranths thrive, or at least survive, under droughty conditions. However, for good production under dry conditions supplemental water must be applied. The plants tend to grow very rapidly and they have high leaf areas (and thus high evaporation losses), so to attain top production and maximum palatability they require

ample water.

Upland Areas Good. With a fast-growing leaf crop like this, altitude is little barrier. Amaranth was a mainstay of ancient South American civilizations, produced at about the highest elevations known to agriculture.

Beyond Africa

Nothing restricts these plants to Africa. Prospects elsewhere are excellent. Indeed, the leafy amaranths have reached their greatest development in Asia. Furthermore, many species from this genus are cultivated in Mexico as well as in Central and South America. And in the Caribbean, of course, they are a mainstay of the traditional cuisine.

USES

This is a multiple-duty crop.

Leaves Leaves, young stems, and young inflorescences are eaten as potherbs. Although much of the pigment leaches out on boiling, the leaves retain a pleasant green color. They soften up readily, requiring only a few minutes cooking, which helps avoid excessive nutrient loss. Unlike some African potherbs, they need no added soda or potash to make them palatable. The leaf is also tossed into soups and stews. The boiled leaves may be rubbed through a fine sieve and served as a puree.

Salad Plant Very young leaves may be used in a mixed salad. Sometimes the whole plant is pulled up after it has developed eight or twelve leaves, and used directly in salads. The leaves, their petioles (stalks), and the plant’s young growing tips are sometimes used in fresh green salads also. The flowers, however, are inedible.

Seeds Several species, including Amaranthus cruentus, A. hypochondriacus, and A. caudatus are grown for their grain-like seeds. Although small, these seeds occur in prodigious quantities. In carbohydrate content they equal cereals such as wheat, but have more protein (over 17 percent in some strains) and more oil. When heated, amaranth grains burst and take on a toasted flavor not unlike that of popcorn, which is very appealing. However, in many areas, they are more often parched and milled into flour. Bread made this way has a delicate, nutty flavor and is used notably by gluten-sensitive individuals. Pancake-like chapatis made from

amaranth are a staple in the Himalayan foothills.

Stems While most leaf amaranths are about 60 cm high, some varieties reach 2 m. It is reported that Singaporeans peel the stem of one of these tall forms and eat it separately. The report notes that to the taste buds they are “excellent.”7 In Bangladesh, special cultivars (of Amaranthus cruentus) are grown for the stems (food).

Decoration Amaranths are well known ornamentals, used worldwide to brighten window boxes, gardens, parks, and public buildings. The flowers can be strikingly attractive with bright colors and showy form.8 Even without flowers some types are decorative. Certain amaranths have red striations in their green leaves due to the presence of anthocyanins. These can be very attractive and (like the tiger leaf variety in Taiwan) edible too.

Feeds Vegetable amaranth can also be used in feedlots for cattle or other intensively reared animals. In the early 1990s a husband-and-wife scientific team carried seed from Pennsylvania back home to China. The seed was from grain amaranths, and they expected to foster a new cereal-like food crop for their country. Instead, Chinese farmers adopted it for forage. Subsequently, it has become very popular in every one of the 29 provinces and is now grown by an estimated one million farmers who keep a pig or two around the house.

Other Uses It is reported that in South Africa’s Queenstown district amaranth greens are eaten only by women, who believe—perhaps with good reason—that the young tops promote the flow of milk. The attractive flowers make Amaranthus cruentus a suitable species for honey production.

NUTRITION

The nutritional quality of amaranth greens is not dissimilar from that of better-known leafy vegetables. However, they tend to accumulate more minerals, notably iron and calcium, and amaranth greens rank at the top when measured against other potherbs.

Their exceptional protein quality makes them useful supplements to cereals and root foods. Protein levels in the leaves are reported around 30

percent.9 Protein quality is high as well. The amino acid composition of Amaranthus hybridus leaf protein, for example, shows a chemical score of 71, comparable to spinach. Elevated levels of the nutritionally critical amino acid lysine have been found in the leaves of 13 amaranth species. This makes it leaf protein a very good supplement to cereal grain. In India, weaning foods have been fortified with amaranth leaf flour.

This shade-loving crop can be fitted in around various taller plants, such as bananas, cassava, and trees. Amaranth greens are mostly grown, harvested, and marketed close to home, and women are the prime producers. Indeed, in several dozen nations this popular plant forms a crucial part of both rural economy and female existence. Here in Benin, a villager uses palm leaves and a bowl of water to sprinkle the amaranth bed in her home garden. (G.J.H. Grubben)

Vegetable amaranths are important sources of vitamin C as well as abundant precursors for producing vitamin A, whose lack blinds thousands of children each year.10

The minerals of importance in amaranth leaves are calcium and iron. Some doubt exists as to their availability in the human body, yet the contribution to people deficient in iron seems to be considerable.

HORTICULTURE

Amaranth is an important market vegetable grown by professional vegetable farmers. It is estimated that in Indonesia 20,000 hectares are planted per year. Amaranths are also cultivated in home gardens for family use, with any small surplus being carried to the village market in the form of tiny bundles of plants tied in bush fiber. The plants are sown virtually year-round in the tropics, and multiple cropping is possible due to its short life cycle (about 8 weeks).

Propagation is generally by direct seeding. Normally, the small black seed is broadcast very thinly (a seeding rate of 2 g per m2 has been suggested) on prepared beds. The tiny seeds are covered with a little soil (a depth of a little less than a centimeter being recommended). The seed may be sown in nursery beds and subsequently transplanted to the field as seedlings.

Given sufficient rainfall and warm weather, growth is rapid. Within a month, indeed often within three weeks, the seedlings are big enough for eating or for transplanting. Typically, the plots are thinned at this stage, leaving the strongest and best plants. The seedlings weeded out are usually quickly washed and dumped into the cooking pot, roots and all.

Various expedients are employed to prolong leaf production. Repeated pruning is one. Another is pinching out the plant’s growing tip, which 1) forces branching and the production of new and tender lateral growth and 2) suppresses any tendency toward early flowering. Keeping the plants thoroughly watered is a third method for extending the season. This lessens any tendency toward drought stress, which can trigger early flowering.

No matter what methods are used, eventually every plant proceeds to flower. Their value for food then plummets, and the plants are removed or let go for seed.

Fertilization with nitrogen stimulates vegetative growth and boosts yield substantially. To generate the greatest amount of the tenderest leaves, the

|

10 |

According to the USDA, a 100g bowl of cooked leaves can provide more than half the daily adult needs for vitamin A; see www.ars.usda.gov/nutrientdata for additional information on thousands of foods, including a few in this report. |

plants should be well watered and the soil fertilized, preferably with manure, compost, or nitrogenous fertilizer, during the period of active growth.

HARVESTING AND HANDLING

The plants grow rapidly and may be harvested when they reach a height of 30 to 60 cm. Although the whole plant can be uprooted, most are cut back, which both produces a harvest of leaves and encourages lateral growth. As many as 10 weekly harvests have been reported.

If the entire plant is harvested, a garden plot of 10 m2 can yield 20 to 25 kg of tasty vegetable. If the leaves and lateral shoots are picked individually several times over, the same small plot can average 30 to 60 kg total yield. On a per-hectare basis, vegetable amaranth yields are generally in the range of 4 to 14 tons green weight. However, harvests as high as 40 tons per hectare have been reported.11

It is traditional in West Africa to soak the plant in water before toting it to market. This gives the leaves a fresh look. Typically the leaves are arranged in bunches, spread on a raffia tray, and hawked in market stalls or in the street. Since they lose moisture rapidly, the leaves are regularly sprinkled with water whilst awaiting a buyer.

LIMITATIONS

The grain’s small size makes this crop tricky to plant. To ensure good germination the seeds must be close to the soil surface, which means that a hard rain or even a flush of irrigation water can wash them all away. The whole planting is thus often protected with a thin covering of grass mulch, which is removed after germination. This vulnerability is also a reason why some farmers sow the seeds in nursery beds, where the plants can be crammed together and protected fairly easily. Then, when the plants are beyond this danger, the farmer transplants them into the production plot. This is a particularly useful method to use during the rainy season.

The tiny seeds—about the size of sand grains—are also difficult to spread evenly across the soil surface. To get around this, the seeds are mixed with sand. Sowing the combination helps space out the plants and attains uniform dispersal.

Slugs and snails often severely damage young plantings, but the worst enemies of amaranth leaves are leaf-chewing insects. Larvae of moths and butterflies, as well as leafhoppers, leaf miners, grasshoppers, and leaf-

feeding beetles may very quickly decimate a planting. This is a problem without a universal solution at present. One useful practice is to cover the bed with a screen fine enough to keep the creatures out. This is of course cumbersome and tedious, but can be effective in the tiny plots in which vegetable amaranths are typically grown. Commericially, some amaranths are grown in screen or net houses that keep out all insects.

Diseases are also a problem. The plants are susceptible to viruses as well as fungal maladies, especially when they are young and the weather is damp. Generally speaking, vegetable amaranths grow poorly during long periods of cloudy, wet weather. During monsoon, for example, diseases such as damping-off (from Pythium and Rhizoctonia) can become serious. To reduce such diseases, the seedbeds must be well drained and located in sunny sites. Manuring can reduce or eliminate some of the attacks by strengthening the plants. Various fungicides have been successful also.

The C4 form of photosynthesis lends Amaranthus species a special competitive edge, to which is attributed their wide geographic dispersal and compatibility with diverse conditions. This is also why many amaranth species have turned into weeds. They are not, however, monsters of the weed world, just commonplace companions that pop up in the strangest spots, and in some of which they’re unwanted.

Although the fresh leaves of some vegetable cultivars can glow with something akin to red fire, when they are boiled the brilliant pigment dissolves in the hot water. The leaves come out emerald green, but the cooking water turns dark and far from pretty.

That cooking water should be tossed out because it contains more than just pigment. All leafy vegetables accumulate antinutritional factors, including oxalic acid, betacyanins, cyanogenic compounds, saponins, sesquiterpenes, polyphenols, and alkaloids such as betaine. Amaranth is no exception, and all these compounds, which interfere with our ability to utilize nutrients, are reported in various Amaranthus species. All, or perhaps most, of the harmful compounds are leached out in that cooking water.

The young and very tender leaves have the least amounts of these undesirable materials, which is why the plants should be picked early and often. It is also why they should be well watered, fertilized, and generally kept lush and vigorous and freshly formed.

NEXT STEPS

As noted, vegetable amaranth is in a sense invisible to the authorities. Now is the time to open everyone’s mind to the crop’s promise. The primary monograph on it was published decades ago.12 That and other books highlighting such tropical vegetables need to be available, widely

disseminated, and revised, helping researchers engaged in improving global food supplies to pay these plants heed. Indeed, a worldwide collegial partnership to foster greater use of vegetable amaranths is worth mounting.

Horticultural Development Selection and crossbreeding is one area that could bring rapid advances. Amaranthus species demonstrate high levels of variability in leaf size, leaf shape, branching, bolting pattern, growth and regrowth ability, and color. Indeed, the vast wide geographical spread of the genus has produced many landraces, and in their present undeveloped state amaranths offer more genetic diversity than do many much better understood crops. The huge gene pool in widely separated areas can be tapped for the future development of the crop. This is an excellent genus as well as an excellent time in history for plant explorers and local plant lovers to get engaged.

One of the least known and least developed species is Amaranthus thunberghii, a semi-wild species native to southern Africa. This seems to have exciting potentials and clearly deserves increased attention. It grows very fast and is resistant to water stress. It is also tolerant to many insect pests such as aphids, fall armyworm etc. A. thunberghii has a more prostrate growth habit than its relatives, which may or may not be a benefit. It has been classified as an aphid-trap plant, which opens up intriguing possibilities for research endeavors.

Although vegetable amaranths have been neglected, this dereliction is, as we’ve said, not universal. Asian growers have been making selections by decades. Named varieties suitable for widespread culture are available from seed companies in Hong Kong, Taiwan, the United States, and elsewhere; many can be located on the internet. These “elite” forms are probably the most technologically advanced and most thoroughly developed forms.

Regarding vegetable amaranths, much crop improvement has been done, but more could be accomplished by studies of:

-

Pest and disease resistance;

-

Nutrient uptake and nutrient content at different stages of growth;

-

The yields from clipping versus successive planting;

-

Regrowth after harvest (“ratooning”) and the best height at which to clip the plant and the best intervals between clippings;

-

Seed production and farmer-selection techniques;

-

Leaf-to-stem ratio;

-

Delayed flowering;

-

Planting and cultural practices for efficient use of land, water, and fertilizer; and

-

Crop rotation to avoid soil-borne diseases.

Also needing study is the forage use of leafy amaranth. The recent

Chinese experience is especially illustrative of the potentials and the possible means for feeding pigs with “pigweed.”

Food Technology Deserving of research and testing are:

-

Food quality, including tenderness and storage methods to prolong the life of the harvested produce;

-

Leaf color and antinutritional factors. It seems likely that the bright red and purple-leafed types are the least desirable as foods;

-

Accumulation of antinutrition factors in response to type and quantity of fertilizers and soil;

-

The variation in flavor among varieties;

-

Effect on nutrient retention by processing, such as boiling, steaming, or drying (for later availability during the dry season);

-

Provitamin A and iron bioavailability;

-

Product development;

-

Toxicological studies; and

-

Nutritional studies, such as supplementation effects.

Actually, some research in these areas has already been conducted and efforts are needed to make the results more widely known and better used.

Vitamin A On the face of it, amaranth leaves could be an important remedy for vitamin-A deficiency, one of the world’s horrors that is subject to increasingly intense outside interventions. Many or most of the programs could incorporate vegetable amaranth. Benefits could accrue not only to Africa but to Indonesia (a country notable for this blindness-inducing affliction) and other parts of Asia.

Leaf-Protein Isolates A future promise of vegetable amaranths is the development of leaf-protein concentrates.13 Compared with most other species, amaranth leaf protein is highly extractable. In one trial, amaranth had the highest level of extractable leaf protein among 24 plant species studied. During the extraction of protein, most other nutrients are extracted as well: for example, provitamin A, polyunsaturated lipids (linoleic acid), and iron. Heating or treating the extract with acid precipitates the nutrients as a leaf-protein concentrate. In the process, most harmful compounds are eliminated, as they remain in the soluble phase. The green cheese-like coagulum is washed with water slightly acidified with dilute acetic acid (vinegar) to reduce further amounts of possible antinutritive factors. The resulting leaf-nutrient concentrate is especially useful for young children and

other persons with particularly high protein, vitamin A, and iron needs. The fibrous pulp left after extracting the amaranth greens is a suitable feed for animals. The protein quality of the amaranth leaf-nutrient concentrate (based amino acid composition, digestibility, and nutritional effectiveness) is excellent. It is, however, species dependent, probably because of the presence of secondary substances.

Special Interest Projects It has been reported that amaranth is highly suitable for incorporation into crop rotations. It is usually unaffected by common soil diseases such as nematodes, fungal, and bacterial wilt.

Recent reports claim that amaranth benefits from intercropping with species such as celosia and/or jute (Corchorus). Further confirmation is in order because this could be an exceptionally important finding. Rotations between these rather similar potherbs could be advantageous to nutrition and dietary variety as well as yield.

SPECIES INFORMATION

Botanical Name Amaranthus spp.

Family Amaranthaceae

Common Names

Afrikaans: hanekam, kalkoenslurp, misbredie, varkbossie

Congo: bitekuteku (Amaranthus viridis, Kinshasa Province)

English: African, Indian, or Chinese spinach, tampala, bledo, pigweed, bush greens, green leaf,

French: calalou, callalou

Spanish: bledo (Central America)

Fulani: boroboro

Ghana: madze, efan, muotsu, swie

Sierra Leone: grins (Creole), hondi (Mende)

Hausa: alayyafu

Temne: ka-bonthin

Philippines: kulitis (Ilongo), uray (Tagalog)

Indonesia: bayam itik, bayam menir (Java), bayam kotok (Sumatra)

Thailand: pak-kom

Nigeria: efo, tete, inene

Jamaica: callaloo

Tswana: imbuya, thepe

Venda: vowa

Xhosa: umfino, umtyuthu, unomdlomboyi

Zulu: imbuya, isheke

Malawi: bonongwe

China: hiyu, hon-toi-moi, yin choy, hin choy, een choy, tsai

India: Ranga sak, ramdana, rajeera, lal sak, lal sag

Malaysia: bayam puteh, bayarn merah

Caribbean: callaloo, calaloo, etc.

Description

Amaranthus species are herbaceous, short-lived annuals. The plants are upright and sparsely branched. The stems are erect, often thick and fleshy, and sometimes grooved. Dwarf forms, about 60 cm high, are best for the small garden. The leaves are normally alternate and are relatively small (5-10 cm long), but the lines grown as vegetables mostly have leaves longer than normal. The leaves show much variability in shape, color (principally green or red, but some varieties are purplish with the pigment betalain). The flowers are small, regular, and unisexual and are borne in abundance in terminal or axillary spikes. The seeds are small, shiny, and black or brown.

Distribution

Within Africa Several species of amaranth are in cultivation but Amaranthus cruentus (A. hybridus), A. blitum and A. dubius are the most widely grown in Africa and are particularly important in West Africa.14 Hybrids between species and varieties exist, some of which have been designated as species or subspecies.

Beyond Africa Several species exist depending on the region in the tropics. For example, Amaranthus tricolor is mostly found in East Asia, China, and India (where amaranths are especially ancient and diverse) while A. caudatus is common (as a cereal) in the Andean nations of South America and throughout the Himalayas, and A. dubius (as a vegetable) in the Caribbean, India and China. A. hybridus is grown for grain or vegetable production in the southwestern United States, China, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Mexico, Thailand, Philippines, Nepal, the Caribbean, and most likely many other places.

Horticultural Varieties

Unlike the crops in other chapters, this one occurs as separate species, including the following:

Amaranthus cruentus L. This grain type has a long stem and bears a large inflorescence. A very deep red, dark-seeded form of the species, sometimes known as blood amaranth, is often sold as an ornamental in commercial seed

packets. Like corn, sweet potatoes, peanuts, and other American crops, Amaranthus cruentus was evidently introduced to Africa by Europeans. But then it passed quickly from group to gruop outrunning European exploration of the interior, so that Livingstone and others found it already under cultivation when they arrived. The white-seeded form is used as a cereal. The black-seeded version is the one used as a vegetable, and it has probably been used that way in Africa since the 16th or 17th centuries.

Amaranthus dubius Mart. ex Thell. This weedy species is a green vegetable of West Africa and the Caribbean, and is found in Java and other parts of Indonesia as a home garden crop. One of its best varieties, the cultivar ‘Klaroen,’ is particularly popular in Suriname and has been introduced in Benin and Nigeria. This fast growing, high yielding plant has distinctive dark-green, broad, ridged leaves and is considered very palatable. It is the only known tetraploid (2n=64) in the genus.

Amaranthus hybridus L.15 One of the world’s most common leafy vegetables, this weedy herb originated in tropical America, but is now spread throughout the tropics and is a frequent component of kitchen gardens. It also grows wild on moist ground, in waste places, or along roadsides. The plant is fast growing, requires little cultivation, is resistant to moisture stress and produces a good yield of grain in sorghum-like heads. The size and color vary greatly. Red-stemmed varieties are usually planted as ornamentals; green varieties are the ones employed as vegetables.

Amaranthus blitum L. This widely distributed species (also known as A. lividus) is well adapted to temperate climates and has a number of weedy forms that come with either red or green leaves. It promises to allow the development of highly palatable crossbred vegetable amaranths. In Madhya Pradesh, India, the edible forms, known as norpa, are especially liked for their tender stems. This species is widely eaten in Greece under the name vleeta. It is also grown in Taiwan, where it is known as horsetooth amaranth. A widespread weed of waste and cultivated ground, it is commonly eaten in many parts of Africa. The leaves are soft and the cooked product is sweet tasting and much liked.

Amaranthus tricolor L. Varieties of this species are native to a large area from India to the Pacific islands and as far north as China. It is probably the best-developed vegetable amaranth: the plants are succulent, low growing, and compact, with growth habits much like spinach. They are produced as a hot-season leafy vegetable in arid regions when few other leafy greens are

available. In India, a large number of cultivars are available, especially in Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, and Kerala. Some ornamentals with very beautiful foliage also belong to this species. There are many cultivars in Southeast Asia classified according to leaf color and shape.

Environmental Requirements

Vegetable amaranths need a long warm growing season, and are suited only to the warm-temperate and hotter zones of the earth. If grown in cooler climates they tend to be tough and poor in quality.

Rainfall The crop thrives in areas receiving 3,000 mm of annual rainfall. As it is mostly grown in small plots beside the house, it is frequently watered by hand. Without irrigation it needs an average of at least 8 mm per day of rainfall during its whole season.

Altitude Areas with elevations below 800m are said to be most suitable for cultivation, but the crop can be grown in higher areas. Amaranthus cruentus, for example, thrives in altitudes up to 2,000 m.

Low Temperature All species are very sensitive to cold weather. Plant growth ceases altogether at about 8°C.

High Temperature Most species are tolerant of high temperatures and thrive within a temperature range of 22-40°C. The plants establish best when soil temperatures exceed 15°C. Optimum germination temperature varies between 16°C and 35°C.

Soil Although most amaranths tolerate a wide range of substrates, a light, sandy, well-drained, and fertile loam is desirable. Soils with a high organic content and with adequate nutrient reserves produce the best yields. Optimum pH range is 5.5-7.5 but some cultivars tolerate more alkaline conditions.