3

BAOBAB

A very, very long time ago, say some African legends, the first baobab sprouted beside a small lake. As it grew taller and looked about it spied other trees, noting their colorful flowers, straight and handsome trunks, and large leaves. Then one day the wind died away leaving the water smooth as a mirror, and the tree finally got to see itself. The reflected image shocked it to its root hairs. Its own flowers lacked bright color, its leaves were tiny, it was grossly fat, and its bark resembled the wrinkled hide of an old elephant. In a strongly worded invocation to the creator, the baobab complained about the bad deal it’d been given.

This impertinence had no effect: Following a hasty reconsideration, the deity felt fully satisfied. Relishing the fact that some organisms were purposefully less than perfect, the creator demanded to know whether the baobab found the hippopotamus beautiful, or the hyena’s cry pleasant-and then retired in a huff behind the clouds.

But back on earth the barrel-chested whiner neither stopped peering at its reflection nor raising its voice in protest. Finally, an exasperated creator returned from the sky, seized the ingrate by the trunk, yanked it from the ground, turned it over, and replanted it upside down. And from that day since, the baobab has been unable to see its reflection or make complaint; for thousands of years it has worked strictly in silence, paying off its ancient transgression by doing good deeds for people.

All across the African continent some variation on this story is told to explain why this species is so unusual and yet so helpful. Indeed, dozens more stories surround the baobab, a species that not only incites imagination but also induces something akin to reverence. Senegal chose it for its national tree and throughout the lands below the Sahara the sight of a baobab inspires poetry, legend, compassion, even devotion. Africans everywhere almost instinctively protect each and every one.

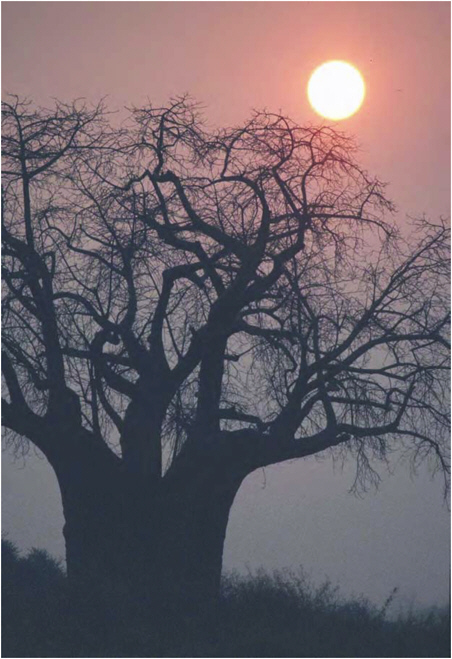

Seen from a distance, the results of the creator’s prank come into clearer perspective: baobabs certainly do seem to grow with their roots kicking the breeze. From the top of the trunk the boughs splay upward at a sharp angle, and they are crooked enough to seem like they should be underground. This eye-catching profile makes each baobab unique, and no matter how many you’ve seen before the shape seems always fresh.

Yet beyond the charms this tree conjures in people’s minds lies a beguiling reality. Of all nature’s living entities this is one of the most fascinating. For one thing, it may be exceptionally long lived, with some individuals claimed to be over 1,000 years old.1 It is also among the biggest and bulkiest of all living organisms, having a trunk sometimes half as broad as it is high.2 This squat stalk, its smooth surface pocked and slit as if stigmatized, is often hollow. Some monstrous specimens actually enclose a trunk space bigger than that found inside a small house. In dry areas they are commonly co-opted as village cisterns. A single bulbous stem has been known to store as much as 10,000 liters of fresh clean water. No wonder another name for baobab is bottle tree.

It is also one of the most useful living entities. On a practical level, the Africans’ veneration arises because the baobab is vital to life. The bark fuels cooking stoves, pottery kilns, and baking ovens. The flexible fiber found in the layer immediately beneath the bark provides cord and coarse fabrics. The fruits are eaten with food or stirred into drinks, and provide exceptional quantities of vitamin C and other nutrients. The seeds are roasted and made into a sort of creamy butter.

The living trees are useful in their own right—not only providing shade but often providing the only splendor in an otherwise sere landscape. They also constitute handy landmarks for travelers,3 gathering points for villagers, and silent witnesses to long abandoned villages. Nothing grows around the base, a feature emphasizing the profile, not to mention the self-sufficiency, solitude, and apparent strength of this surprising species.

In a separate volume we detail baobab fruit as well as most other products from the tree. Here we focus on the leaves and their uses.

Baobab leaf is a staple of many populations in the savanna lands just beneath the Sahara. In most places between the westernmost tip of Senegal and Lake Chad half a continent to the east this leaf vegetable is among the most common of foods. Bursting into foliage a little before the rains begin, the trees remain green until a little after the rains have ceased. In a food class renowned for transitory availability, baobab is thus a leafy vegetable that yields through a very long season.

Nature’s most recognized silhouette? Baobabs are so distinctive there is little chance of ever mistaking one. These majestic trees are found throughout much of Africa. It is hard to conceive anything more promising for Africa’s long-term future than a native tree beloved by the people, that seemingly lives forever without much maintenance, and that provides nutritional food (William F. McComas, photographed in Tanzania’s Tarangire National Park)

Strangely, it is only in West Africa that baobab leaves contribute to diets in a major way. Eastern and Southern Africa have the tree but seldom consume the leaves. In the continent’s western half, however, thousands of tons are consumed annually, and baobab greens are a commonplace in the markets as well as the daily meals of millions.

Baobab leaf is sometimes steamed and eaten as a side-dish like spinach, but most goes straight into soups, stews, sauces, relishes, and condiments that end up being poured over the yam, cassava, maize, millet, sorghum, and so forth to complete the main dish.4 A recent survey in Mali found that baobab leaves occurred in 41 percent of these “soups.”5 This widely used name does something of an injustice to such concoctions, which are more akin to sauces. The leaves not only add flavor and nutritive value they thicken the mixture and give the dishes their slightly slippery texture as well as their popularity. Although baobab leaf is the most common base for these sauces, many other things, including eggplant, okra, jute,6 tomato, onion, green peppers, and (when available) fish or meat, are also tossed in. Throughout that vast region this vegetable blend ladled like gravy over starchy staples is the most common cooked food of all.

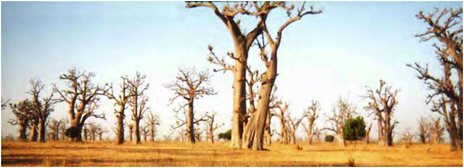

In collecting their leaves for the evening meal, people are constantly plucking and pruning the trees, with the result that baobabs never get a chance to look natural and complete. Indeed, across West Africa they become so thoroughly picked over they look ragged, ratty, or even in the final phase of succumbing to some wasting disease.

Following the flush of new leaves early in the rainy season any surplus harvest is put aside to dry. In desiccated form, the leaves keep well— surprisingly without losing their glutinous polysaccharides—and many months later they can be brought out and used to thicken soups just like new.

In cities, where baobabs aren’t available for the picking, the leaves for the evening meal must be purchased. For many people finding the baobab money becomes a never-ending struggle: Making baobab-leaf sauce can cost the equivalent up to even a dollar a day, a fearsome price in that area, where making more than that for a day’s work is rare. On the other hand, countrywomen derive small but important income from selling the leaves.

In nutritional power baobab leaf is quite surprising. According to various reports it contains 11 to 17 percent crude protein and with an amino-acid composition comparing favorably with that considered the ultimate for human nutrition. Isoleucine, leucine, lysine, phenylalanine, tyrosine, threonine, tryptophan, and valine all occur in adequate amounts. The lysine

|

4 |

Baobab is, for instance, a major food of the Hausa-speaking peoples. A traditional Hausa lunch includes danwake, which is typically a blend of sorghum, sweet potato, cassava, potash, peanut oil, dried chile, cowpea, and baobab leaves. |

|

5 |

The next most popular, at 26 percent, was okra—a crop dealt with in Chapter 16. |

|

6 |

Although the jute used to make sacking can be eaten, the species cultivated as a vegetable is its relative Corchorus olitorius. |

level is especially notable, since people usually eat baobab leaf along with cereals or roots, which are both comparatively deficient in this critical dietary ingredient. Wherever meat, milk, or eggs are hard to come by or excessively costly—which means most places—the leaves contribute a protein of vital quality.

Beyond quality protein, young and tender baobab leaves contain good levels of provitamin A, and it is notable that the trees thrive in the kind of dry and impoverished locales where a lack of vitamin A constitutes one of the worst nutritional deficiencies. In addition, the levels of both riboflavin and vitamin C have proved adequate in the leaf samples tested so far.

The leaf is moreover a good source of minerals, including in its tissues calcium, iron, potassium, magnesium, manganese, molybdenum, phosphorus, and zinc. A detailed analysis so convinced the authors that they wrote: “in terms of both quality and quantity, baobab leaf can serve as a significant protein and mineral source for those populations for whom it is a staple food.”7

All in all, then, this is a tree with a capability to hold its own against cabbage, spinach, carrots, and the other vegetables that now capture the focus in textbooks, scientific reports, and foreigners’ image of first-class greens. Seen in overall perspective, baobab is a native resource that provides the continent a tree cover while providing the people food. And, given some support and attention, it could contribute a lot more to the environments, nutrition, economies, and personal income (particularly women’s income) of many—if not most—African nations.

Of particular importance is the leaves’ potential to help women and children who are currently beyond the reach of vitamin-support programs. In Sub-Saharan Africa, some 3 million children suffer blindness caused by insufficient vitamin A. Two-thirds of those die from increased vulnerability to infection. Their mothers are hardly better off: The World Health Organization reports that women suffering vitamin A deficiency face a significantly greater risk of death during pregnancy. Vitamin A deficiency is also common in AIDS patients, and is associated with an increased mortality rate. Baobab leaf just might be a key vehicle for delivering such people from the evil of malnutrition.

PROSPECTS

At this moment, rural peoples’ dependence on baobab products seems to be rising. Probably, though, this is not due to greater appreciation for the tree but due to soaring populations, falling economies, and shrinking forests. The potential for boosting this species into a vastly greater vegetable crop would

Well-picked-over baobab forest in Senegal. The leaf of the much beloved baobab is a staple of the savanna lands below the Sahara. In an area stretching across half the continent, this vegetable ranks among the commonest foods. Bursting into foliage a little before the rains begin, the stately trees remain green and edible until a little after the rains have ceased—often half the year. In addition, any surplus harvest can be dried, in which form, the leaves keep well even under the climatic challenges of rural Africa. (Sherman Lewis)

thus seem to be exceptional.

The main first use is likely to be small-scale commerce and subsistence use. Traditionally, baobab has not been deliberately cultivated for major commercial production, however farmers in Burkina Faso and Senegal have begun organizing its production for the local markets. Reportedly, these ventures have proven profitable.

Furthermore, extending the use of baobab leaf to regions beyond West Africa offers possibilities for enhancing both the crop and its benefits to nutrition, prosperity, and the environment. In addition, as we have said, there are excellent prospects for using baobab in health campaigns, playing off the wisdom of traditional diets.

All in all, this is a species that can get to the heart of the humanitarian needs of the most malnourished continent, not to mention the heart of rural poverty and environmental destruction.

Within Africa

As a species that speaks to the African spirit—one that, in a sense, stands for Africa—the baobab has promise almost everywhere, but the commercial and humanitarian prospects are somewhat more limited.

Humid areas Uncertain prospects. Most observers would today dismiss the baobab for cultivation as a humid lowland resource. However, in certain areas the trees thrive where annual rainfall reaches 1,250 mm, actually growing with almost twice-normal speed. Indeed, along the Kenyan coast baobab grows vigorously where annual rainfall ranges up to 2,000 mm. Thus, on the issue of its tolerance of lowland tropical conditions a grave misconception might possibly be inhibiting expectations and initiatives.

Although heat and humidity may slash fruit production, they don’t affect the leaves. They may in fact force even greater production of foliage. Of course, this tree grows in the open and cannot take the shady conditions of a forest.

Dry areas Excellent prospects. Baobab is common throughout West Africa’s savannas, where the Sahara Desert to the immediate north is the dominant climatic influence. In this often-parched precinct baobab is not only the biggest but also arguably the best tree around. It has even been dubbed “Mother of the Sahel.” People like the leaves and the production in this zone could readily be boosted for the benefit of children’s eyesight, the environment, the savanna scenery, AIDS patients, and all who eat there.

Upland areas Unknown prospects. The baobab normally occupies sites below 600 m elevation, which has been considered the species’ upper limit. Nonetheless, there are indications that—within reasonable limits of temperature and rainfall—niches to accommodate these trees could be found at elevations far above that supposed ceiling.

Beyond Africa

Although the baobab grows satisfactorily outside Africa, it seems unlikely to become a significant vegetable resource in locations where it is not now employed in that manner.

USES

In overall utility, perhaps no tree on earth surpasses baobab.

Vegetable As mentioned, the young leaves are used as a soup ingredient. Large quantities are consumed. The amount used in preparing soup, for example, varies depending on the taste of the cook and her level of prosperity, but one survey of 831 preparations in three Zaria (Nigeria) villages found that baobab leaf constituted between 2 and 3 percent of the whole soup.

Typically, leaves are ground up and sprinkled into the pot in which sauces are being prepared. Taken all round, this is the main form in which leaf is employed. Hausa-speaking peoples in particular consider it the main ingredient of a soup called miyar kuka (kuka being their name for dry baobab leaves). But all across West Africa these popular baobab-leaf soups are most often labeled with the Wolof name, lalo.

In Ghana baobab-leaf soup is used as weaning food. Research has shown it to be of such nutritional quality that it may be therapeutically useful in the management of protein-calorie malnutrition—the biggest baby-killer of all, and a common feature across Africa.

Forage Baobab leaves are among the livestock owner’s favorite forages. They become vitally important at the beginning of the rainy season, a time of year when the old pasture has been eaten out and the new has yet to regrow. The tree’s roots, when tapping into underground moisture, help generate an early flush of foliage that can make the difference in bridging this feed gap. The leaves are also eaten by large caterpillars that are themselves a valued food.

Medicinal Uses Baobab leaf powder is credited with various medicinal powers and is commonly taken as a general tonic as well as a treatment for anemia and dysentery. The leaves are also used in treating other afflictions: asthma, kidney and bladder disease, insect bites, fevers, malaria, sores, and even copious perspiration.

Beyond the leaves, there are of course other uses for the baobab. These are highlighted in the companion volume, but can be summarized as:

Fruits Reaching almost the size of melons, baobab fruits enclose packets of chalk-like pulp with an agreeable acidic taste. That floury solid is peculiarly refreshing, a feature especially appreciated in the hot zones where the tree mostly occurs. Although much goes into tasty and nutritious drinks, most is eaten with milk or with milk and porridge. The fruits are also sucked as a snack or ground into flour and added to cereal dishes. The seeds are not only roasted and made into a sort of creamy butter, they are used to strengthen soups.

Seeds Embedded in the fruit pulp are seeds whose kernels not only are tasty but high in protein. They too are widely eaten. They are sometimes prepared by roasting. Indeed, during the “hungry season,” roasted baobab seeds become many people’s staple. Their flavor has been likened to that of almonds.

Flowers As a source of nectar baobab flowers are excellent. All in all, these trees contribute greatly to Africa’s honey supply.

Trunks The bark often forms cavities deep enough for animals, and even people, to find homes. The gigantic trunk is occasionally coopted for use as storage sheds, bus stops, bars, dairies, toilets, watchtowers, grain stores, shelters, stables, or even tombs. Water stored inside may keep for months or even years without fouling (as long as the hole in the trunk is carefully covered to block contamination from the outside).

Roots The tender root of the very young baobab is edible. Older roots are not, but they provide a strong red dye.

Amenity Plantings Baobabs are planted for shade, shelter, boundary-markers, and general beautification. They typically cluster around villages, but each one—even standing alone and unattended in the vast savanna—is individually owned or at least commandeered by “squatters” who first prune off the branches—partly to increase productivity, but mainly to secure their claim to the tree for the season. Large groupings are either part of living villages or silent witnesses to dead ones. Sometimes it is hard to tell whether people naturally settle close to these useful trees or vice versa.

Fiber The stringy inner bark yields a particularly strong and durable fiber that provides such things as rope, thread, strings for musical instruments, and a paperstock tough enough for bank notes. Some is woven into fabrics that are valued for making (among other things) the bags used for hauling and storing everyday goods. These fabrics can be waterproof, and Senegalese artisans weave them into rainhats and even drinking vessels.

Fuel The thick bark, the fibrous husks of the fruit, and the dense shells of the seeds make useful fuels. Although the bark is burnable, the spongy material making up the bulk of the trunk (i.e. the part inside the bark) is usually too sodden to even smolder until thoroughly dry.

NUTRITION

Baobab leaf provides at least four nutritious ingredients: protein, vitamins, minerals, and dietary fiber.

Protein As noted, fresh leaf samples are protein rich. Leaves analyzed in the above-mentioned report contained 10.6 percent protein.8 The amino-acid composition—the one comparing favorably to the “ideal”—was valine (5.9 percent), phenylalanine/tyrosine (9.6 percent), isoleucine (6.3 percent), lysine (5.7 percent), arginine (8.5 percent), threonine (3.9 percent), cysteine/methionine (4.8 percent), and tryptophan (1.5 percent). In sum, there were adequate amounts of all the essential amino acids excepting the two, cysteine and methionine, containing sulfur.

Vitamins Baobab leaves contain a very high level of the carotenoids that give rise to vitamin A. The actual amounts (9-27 mg per kg) depend on the tree and on the method of drying. The carotenoids are not unlike those found in carrots (and mangoes), but are less concentrated and less available than their carrot counterparts.9

Recent research determined the levels of provitamin A for various leaf types, drying methods, and processing systems.10 It was found that drying the leaves in shade rather than sun doubled the leaf powder’s provitamin A content—a very important discovery for those using baobab in health campaigns. The age of the tree had no effect on provitamin A levels but leaves from small-leafed trees contained more than from large-leafed trees.

Minerals The leaf samples are also high in ash (9-13 percent), which includes minerals such as calcium, magnesium, manganese, potassium, phosphorus, iron, sodium, and zinc. In certain samples, however, some of these elements occurred at lesser levels, probably reflecting deficiencies in the soil where the particular tree grew. One test indicated that 100 g of baobab leaves provide about three times the daily calcium requirements, twice the daily magnesium and copper requirements, and four times the daily manganese requirement. It is unclear how available these minerals are in fresh or processed leaves.

Fiber The leaf is also high in crude fiber, with levels of 15 to 18 percent measured. They also have an important amount of mucilage.11

HORTICULTURE

Little is known about how best to cultivate and care for baobab. Whereas the tree is common and well distributed throughout the Sahelian and Sudanian zones, few of the specimens there were deliberately planted—most arising as part of the natural system and subsequently preserved when farmers cleared the land. Concentrations of deliberately planted trees occur mainly in and around village sites.

We have earlier noted that Africans everywhere almost instinctively protect each and every baobab. Part of the reason, of course, is that the trees supply food and traditional medicines for both humans and their livestock. This resulting parkland system, in which the fields are everywhere dotted with trees, is the most widespread form of agricultural production over much of West Africa. Moreover, the practice of fallowing the land after cropping it for several years inadvertently helps native trees such as baobab to regenerate.12

Although this protection and natural regeneration are currently the main means of fostering baobab, the species can be propagated from seed. Simple

treatments are needed to overcome a reluctance to germinate in a timely manner. After a 5-minute soak in boiling water the seeds germinate uniformly and usually within three weeks.

Transplanting bare-root seedlings is satisfactory. For example, on the Seno Plain, along Mali’s border with Burkina Faso, villagers often raise baobabs within their own courtyards and nurture the seedlings until they are 2-3 m tall, then transplant them to the edges of their fields.

Despite a reputation for slow growth, baobab seedlings on favorable sites have been known to reach 2 m in height in 2 years and become 12 m tall in 15 years. Although far above the norm, this shows the potential in the plant given horticultural attention.

Seedlings and young trees need careful protection. In fact, in the open savanna comparatively few small baobabs are ever seen, mainly because they fall victims to cattle, goats, ground fires, or overzealous individuals picking them to death for soup leaves.

Mature trees, however, have few enemies. No serious pest or major disease is known. Neither cattle nor goats do serious harm. Not even over-zealous pickers can seemingly set back a healthy old baobab. Being a trunk-succulent, the tree resists both fire and drought. However, lightning, severe winds, and (in southern and eastern Africa) elephants can break the branches and bring down even the biggest of these botanical monarchs.

HARVESTING AND HANDLING

There is no secret about harvesting baobab leaves. People (mostly small boys) literally clamber over the trees, plucking off every young leaf within reach. Ladders of steps are often slashed into the side of trees to allow easy access to their upper stories. Many trees are kept basically denuded throughout their life. Some are pollarded, their top branches cut back to the trunk to induce a dense growth of new shoots. In both cases, flowering is suppressed and, perhaps because of that, the leaves sprout in abundance.

Because the leaves are available only during the rainy season, women dry any surplus and store it for use up to a year later, for times when vegetables are not only difficult to find but expensive. This propensity for easy storage also allows the leaves to be sold at the time when the traders pay the best prices. In good years this provides a small, but important, source of income.

In better-watered zones or in village gardens where each tree can be pampered through the dry season, baobabs prosper and often remain in foliage year-round.

LIMITATIONS

Although the leaves are rich in various nutrients, the quantities touted in research reports might not (at least in theory) reflect those actually reaching

the body. At present, no one knows about the digestibility of the different ingredients, but it is possible that phytic acid, oxalic acid, hydrocyanic acid, and tannins occur in high enough levels to interfere with the body’s use of proteins and calcium.

Researchers in Mali discovered that the baobab powders on sale in public markets differed widely in nutrient content. They urged consumers give preference to those with darker green color and a good all-round baobab-leaf smell. “Based on its provitamin A content,” they wrote, “baobab-leaf can be very effective at saving eyesight, but only as long as care is taken to handle the leaves in ways that preserve the vitamin. To maintain a high level of provitamin A level in dried leaves, it is important NOT TO DRY THE LEAVES IN THE SUN. Leaves dried in the sun have only half the provitamin A levels of leaves dried in the shade. [Also] it is recommended to store dried whole leaves rather than dried leaf powder in order to maintain good provitamin A levels. Provitamin A tolerates cooking, but is degraded by overcooking.”

NEXT STEPS

A tree as productive and as important to people as this one is worthy of massive and pan-African research. Programs dealing with food, nutrition, forestry, agriculture, agroforestry, rural development, home economics, horticulture, and other subjects should embrace this species as a potential tool for helping achieve their individual goals. Combining the traditional, Africa-wide knowledge with modern scientific understandings could boost baobab to a far greater furnisher of food from Senegal to Mozambique and Madagascar.

This tree is already so well known that basic research is not essential to progress. Existing knowledge and the germplasm on hand can be used to mount planting and protection programs throughout its range. These can be big or little, concentrated or dispersed, rural or suburban.

Protection As noted in the volume on Africa’s cultivated fruits, baobab is a candidate for self-motivated forestry. Indeed, if a few people take the initiative, it is not inconceivable they will spark an Africawide “Baobab Movement.” Mass-producing saplings for the rural poor seems a good start. Such an endeavor would eventually do more than just feed the growers; it could create a critical mass of trees for producing leaves (as well as fruits and bark fiber) on an industrial scale. The tree would then move from a beloved but scattered village companion into a major continental resource. Although one must wait years for the fruits to form, leaves sprout from the start and the leaf harvest can begin after only brief delay.

One way to foster immediate increases is to raise the juvenile survival rate. With their slim stems and simple leaf form, saplings look too handsome to be baobabs. Thus, although old baobabs are venerated as personal

property, young ones go unclaimed, and quickly fall to ground fires, goats, and galoots stripping the leaves for dinner. This ignorance and mindless plunder are major constraints to further development and need to be reduced by programs that enlighten the populace to the potential inherent even in the skinny little young trees.

To outsiders, West Africa’s tree-dotted savannas may look almost like recreational areas, but they are in fact nutritional ones. Products from various woody species in this parkland agroecosystem feed the rural population throughout the year and also contribute snacks during the period when other foods are scarce. This trees-and-farmland combination is an agricultural system that needs to be preserved; focusing on baobab is one way to help bring that about.

Education Whereas millions of people use baobab, few are aware of its notable health benefits. Although vitamin A deficiency is a chronic health problem in places such as rural Mali, the curative nature of baobab leaves goes almost unappreciated by the masses. In the fight against malnutrition these leafy materials offer sweeping future advances. They are on hand, they are known, and they can be marshaled to help children and others. This can be brought about through education, not excluding advertising.

One reason why more baobabs aren’t planted is that people believe the tree grows so slowly that they’ll never see the results. In addition, many people refuse to plant any species that regenerates spontaneously—why waste effort when nature will do the job for you. Again, education could be employed to motivate millions to plant more baobabs.13

In some areas cultural taboos may slow this species’ greater use. In parts of the Gambia, for instance, baobabs are considered too evil to plant nearby. And in Mali during October and November prices for the leaves drop because it is said that during that “cool” season they cause the lips to crack. There is a need for broad education on what we really know about baobab— and what we don’t.

Expanding the Use Although among the most widespread and most appreciated native plants, only West Africans use baobab much as a vegetable. Elsewhere, the trees abound but the leaves go uneaten. This opens new possibilities, of course, but before the production of leaves is promoted outside West Africa it would be wise to determine why they are rejected there now. According to one report, the trees used for vegetable purposes derive from a glabrous variety, with hairless leaves. The author implied that the tomentose variety, whose leaves are covered in down, furnish good fruit but bad (in the culinary sense) leaves. This perhaps explains the strange

dichotomy of only one region eating the leaf. Should this observation prove true, then the hairless (good-vegetable) types and the hairy (good-fruit) types should be tested throughout the continent. This would involve a swap of germplasm likely to benefit all.

Nutritional Research With their 15-percent crude protein content, the leaves should be a useful source of this vital food type, but the crude fiber and tannins may reduce its digestibility. This needs investigation.

Similarly, the leaves are rich in calcium, but how much is absorbed by the body is uncertain because the leaves also contain gums that may impede its absorption. Phytic acid and oxalic acid, which are known to adversely affect their mineral utilization but whose levels are probably only marginally problematic, may also affect the availability of calcium, not to mention magnesium and iron.

Studies of the fate of vitamin C under various food-processing regimes would provide helpful guidance for best processing practices.

Baobab-leaf could become an important export, but any formal trade will require better governmental policies as well as better processing. The first step is to learn the potentials of the various products as well as the constraints associated with their manufacture and marketing.

Horticultural Development In baobabs grown for edible leaves the selection of elite types is less important than in those grown for fruits. Nonetheless, it seems well worth searching for highly productive forms that can foster and facilitate the species’ progress toward becoming a better vegetable resource. Selection for leaf quality is the necessary research ingredient. Issues might include flavor, digestibility, carotenoid content, and ability to make soups with just the right slipperiness on the tongue. As noted, trees with small leaves have been recommended.

Vegetative propagation would be useful for making such advances, and the best techniques need to be worked out. This alone will foster new plantings, not to mention new profits and perceptions.

The plant’s ecological tolerances and preferences are poorly understood. Although it appears far from picky about where it grows, at least one researcher has noticed “a tremendous response to choice of planting site, even to microsite.”

On the surface, this would seem a good species for developing miniature gardens, as has been done with apples in England. By keeping the trees topped and pruned to human height, the leaves would be always within easy reach. Should this prove feasible, baobabs could be grown and plucked like tea plants. Women and girls could then participate equally in the harvest.14

SPECIES INFORMATION

Botanical Name Adansonia digitata Linnaeus15

Family Bombacaceae

Common Names

Afrikaans: kremertartboom

Arabic: hahar, tebeldis; fruit: gangoleis

Bambara: sira, n’sira, sito

Burkina Faso: twege (Moré)

English: baobab, monkey bread, Ethiopian sour gourd, cream-of-tartar tree

French: baobab (tree); pain de singe (fruit), calabassier, arbre aux calebasses

Fulani: bokki, bokchi, boko

Ghana: odadie (Twi, in the south), tua (Nankani, in the north)

Jola: buback

Kenya: mbuyu (Swahili); mwamba (Kamba); olmisera (Maasai); muru (Bajun);

Malawi: manyika: mubuyu

Malagasy: Bozo (Sakalava dialect)

Mandinko: sito

Manyika: mubuyu

Ndebele: umkomo

Hausa: kuka (dried leaves), miya kuka (soup)

Yoruba: luru

Portugese: imbondeiro

Shona: mayuy, muuyu, tsongoro (seeds)

Sudan: tebeldi, humeira

Swahili: mbuyu

Tsonga: shimuwu

Tswana: mowana

Venda: muvuhuyu

Wolof: bui, lalo (leaf powder)

Zulu: isimuhu, umshimulu

Description

Baobab typically grows up to 20 m tall and its sharply tapered, but very swollen, trunk sometimes reaches a circumference of 30 m. This immense girth and stiff branching give the impression of a bottle full of twigs. A spongy mass of parenchymous tissues fills the thick trunk, which typically becomes saturated with water and is often hollow. The smooth, metallic-gray bark has a remarkable ability to heal any wounds. Roots extend far from the base of the tree and probably account for the dearth of nearby vegetation. There may be a taproot as well, though reportedly not deep.

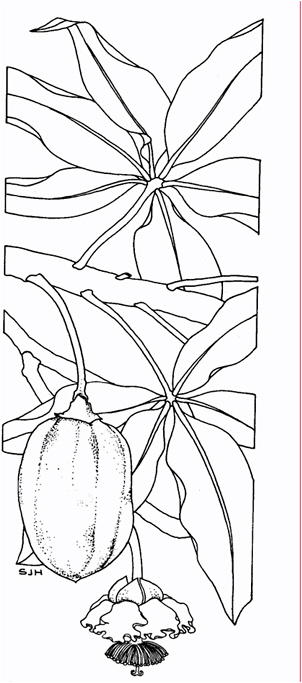

The leaves are compound and digitate, usually with 6-8 oblanceolate leaflets. The common stalk is usually about 8-15 cm long and the individual leaflets lack stalks. Whether in full leaf, in flower, or in fruit, it is one of the most beautiful and fascinating of trees. Whole plantings can become bespangled with white blossoms that attract bats, giving rise to masses of fruits hanging on long stems like ornaments.

Distribution

Within Africa This species is found throughout tropical Africa, but especially in the sub-humid regions and the semi-arid zone to the south of Sahara. Its northern limit (in Senegal) is about 16°N; its southern limit is about 15°S in Angola to 22°S in Botswana and to 24°C in Mozambique (at Chokwe). The species is also a famous feature of the Madagascar landscape, but Adansonia digitata seems not to be native there, the homeland of the genus. It perhaps arrived with Arab traders who carried the seed out of Africa centuries ago.

Beyond Africa Baobabs have long been planted in locations throughout the tropics, and have been introduced into the Americas and Asia. Its widespread occurrence in India, Sri Lanka, and elsewhere around the Indian Ocean is due to Arab traders who carried the seed out of Africa centuries ago. It is also well known in the far north of Australia, and is scattered as an ornamental through much of the tropics.

Horticultural Varieties

No formal varieties have been recorded for vegetable use. However, in the Sahel four baobab types are loosely recognized: black-, red-, and gray-bark, and dark-leaf. Dark-leaf baobab is preferred for use as a leafy vegetable, while the black- and red-bark baobabs for their fruits.

Cultivation Conditions

Generally, baobabs occur in semiarid to subhumid tropical zones. These light-demanding trees do not like the dense tropical forests.

Rainfall Baobabs are most common where mean annual rainfall is 200-1,200 mm. However, they are also found in locations with as little as 90 mm or as much as 2,000 mm mean annual rainfall.

Altitude The tree can be found from sea level to 1,500 m (notably in eastern Africa), but mostly occurs below 600 m.

Low Temperature Baobab is said to thrive where mean annual temperature is 20-30°C. It succumbs to frost. Reportedly, germination is achieved only when soil temperature exceeds 28°C.

High Temperature No limits within Africa. It is adapted to at least 42°C (measured in the shade).

Soil Grows on many different soils but develops best on calcareous substrates and on deep, slightly moist sites. Does not tolerate seasonally inundated depressions with heavy clay soils. Despite this intolerance to waterlogging, it thrives along the banks of rivers such as the Niger. Reportedly tolerates laterite as well as relatively alkaline (e.g. limestone) soils. For reasons not explained, it apparently performs poorly in the sandy “millet” soils of the Sahelian zone.