PURPOSE OF THIS REPORT

At the outset of this study its sponsor, the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE), requested a brief status report about midway through the project. The report would summarize the committee’s information-gathering activities and identify issues within the scope of its task that have risen to the committee’s attention. After holding three meetings that essentially finished the information-gathering phase of the project, the committee wrote this interim status report to meet DOE’s request. The project is scheduled to be completed in May 2007, with a final report that presents the committee’s findings and recommendations. No findings or recommendations are presented in this interim report.

INTRODUCTION

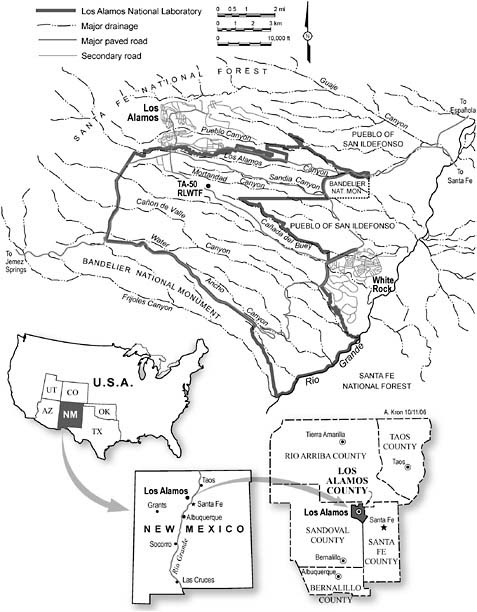

Discharges of wastes from activities associated with the federal government’s Los Alamos site in northern New Mexico (see Figure 1) began during the Manhattan Project in 1943. Now designated the Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL), the site is operated by Los Alamos National Security LLC1 under contract to the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) of DOE. Through past and ongoing investigations, radioactive and chemical contaminants have been detected in parts of the complex system of groundwater beneath the site. Effective protection of groundwater is important for LANL’s continuing operations.

Seven of Los Alamos County’s 12 drinking water supply wells are located on the LANL site. Water from one of these wells is known to be contaminated with limited but detectable levels of tritium and perchlorate. Slightly elevated concentrations of contaminants have also been observed in a group of springs near the site. Some contamination from the laboratory has been carried by stormwater runoff into the Rio Grande River, which provides water to parts of New Mexico.

Under authority of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the State of New Mexico regulates protection of its water resources through the New Mexico Environment Department (NMED). NMED has recently issued an Order on Consent for Los Alamos National Laboratory2 that establishes schedules for additional investigations that will lead to a corrective action decision under the order. New Mexico citizens and citizens’ groups are also actively involved in environmental issues at LANL. The Pueblo de San Ildefonso is located down gradient of the site, and its people have a long-term interest in the quality of groundwater.3

|

1 |

Los Alamos National Security LLC is a consortium of Bechtel, the University of California, BWX Technologies, and Washington Group International. After competitive bidding, DOE selected this consortium to operate LANL in December 2005, and the transition was completed in June 2006. See http://lansllc.com/. |

|

2 |

Usually referred to as the Consent Order. This legally binding agreement among NMED, DOE, and the University of California was signed on March 1, 2005. |

|

3 |

The Pueblo de San Ildefonso is a federally recognized Native American tribal government—one of nineteen pueblos still in existence in New Mexico and one of five Tewa-speaking tribes. The Pueblo’s 30,271-acre reservation (i.e., Tribal Trust Lands) is located in north central New Mexico adjacent to the LANL site (see Figure 1). |

Source: Andrea Kron, LANL

FIGURE 1 Location of Los Alamos National Laboratory in Northern New Mexico. The site is traversed by numerous canyons, such as Mortandad Canyon, which has been studied extensively. Groundwater flow is generally from west to east toward Pueblo de San Ildefonso lands and the Rio Grande. The Radioactive Liquid Waste Treatment Facility in TA-50 is the only location where liquid radioactive waste continues to be discharged to the environment.

The study described in this interim report is funded by the DOE Office of Environmental Management, which turned to the National Academies for technical advice and recommendations regarding several aspects of LANL’s groundwater protection program. The Los Alamos site office of NNSA is the DOE liaison for the study. Results of the study are expected to provide guidance and impetus for dialogue and agreement among DOE, LANL, NMED, and other stakeholders on a focused, cost-effective program for protecting the groundwater in and around the site.

THE COMMITTEE’S TASK

The statement of task for this study is shown in Sidebar 1. The first two subsets of tasks direct the committee to provide answers to questions regarding LANL’s knowledge of potential sources of groundwater contamination and aspects of its monitoring program. The committee’s final report will address these questions and provide recommendations as requested in the last portion of the task statement.

LANL’s presentations to the committee have paraphrased portions of the task statement to emphasize issues of greatest interest to DOE, as follow (Dewart, 2006):

-

Do we [LANL] understand and have we controlled our sources of groundwater contamination?

-

Are we adequately addressing issues of groundwater data quality?

-

Is our groundwater monitoring approach effective in identifying contaminants that may migrate at unacceptable levels to public receptor locations?

Further, LANL is legally bound to meet milestones specified in the Consent Order with NMED (see Sidebar 2), which requires the laboratory to evaluate and remediate, as necessary, contamination in the groundwater by about 2015. The laboratory is therefore seeking advice on whether its current technical approaches are sufficient to accomplish this work.

At the study’s beginning the committee recognized that water is a precious resource in northern New Mexico, and citizens of that state are very concerned that their water supplies be protected. The LANL site itself is located on lands historically occupied by Native Americans and immediately adjacent to several active pueblos. While confining its deliberations to technical issues, the committee included citizens’ concerns in its information gathering and will be mindful of such concerns as it develops its final report.

|

Sidebar 1 Statement of Task This study will focus on specific scientific and technical issues related to groundwater monitoring and contamination migration at LANL as follow:

Potential remedial actions for the groundwater contamination, especially for radionuclide contamination for which DOE is self-regulating; and Monitoring for long-term stewardship. |

|

Sidebar 2 Summary of the Order on Consent for Los Alamos National Laboratory The final order was signed March 1, 2005, by the New Mexico Environment Department, U.S. Department of Energy, and the University of California. Its purpose is to:

The order contains the following:

Noncompliance is subject to enforcement under the Hazardous Waste Act. Source: Bearzi (2006). Also see http://www.nmenv.state.nm.us/hwb/lanl/OrderConsent/03-01-05/Order_on_Consent_2-24-05.pdf. |

CHALLENGES CONFRONTING LANL’S GROUNDWATER PROTECTION PROGRAM

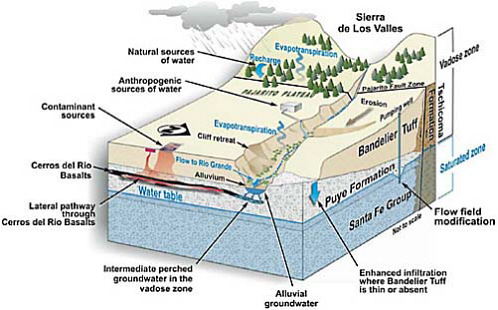

Assessing groundwater contamination beneath and around LANL is challenging because of the long history and variety of wastes released at the site and the area’s complex hydrogeological environment (Robinson, 2006; Vaniman, 2006). The top of the regional groundwater aquifer is typically about 1000 feet (330 meters)1 below the ground surface. The regional aquifer is overlain by discontinuous intermediate aquifers and shallow “perched” groundwater in the vadose zone. These features are illustrated in Figure 2.

Source: Donathan Krier, LANL

FIGURE 2 Representative Geological Cross Section of the LANL Site. Alluvial material is erosional sediment, including gravels, sands, silts, and clays, that is deposited by flowing water. The materials are eroded from higher elevations in the watershed. Small zones of alluvial and intermediate-depth groundwater are referred to as “perched” because they occur in the unsaturated zone above the more laterally extensive and productive regional groundwater aquifer.

LANL has long recognized radionuclide and chemical contamination in groundwater beneath the site. Radioisotopes such as strontium-90 and tritium have been detected in the perched groundwater along with chemical contamination, including perchlorate and metals. The perched groundwater generally contains greater concentrations of contamination than the underlying regional aquifer. Although it appears that discharges from LANL are the major sources of this contamination, there are also off-site sources—for example, wastewater treatment plants near the site—that make the origins and movements of some types of contamination (e.g., nitrate) difficult to understand. In addition, LANL groundwaters contain naturally occurring constituents such as uranium and its radioactive decay products.

There are three recent developments that are challenging LANL’s groundwater protection efforts and which provided impetus for this study:

-

The Consent Order laid out specific milestones that LANL must meet;

-

In fall 2005 chromium concentrations about four times greater than EPA drinking water standards were measured in the regional aquifer beneath Mortandad Canyon (see Figure 1 for the canyon’s location). This level of

-

contamination was not expected at that location, and its discovery brought into question LANL’s understanding of groundwater flows and contaminant migration at the site; and

-

At about the same time, the DOE Office of the Inspector General (IG) determined that the construction of many of LANL’s groundwater monitoring wells did not strictly adhere to Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA) guidance.

The September 2005 IG report responded to allegations regarding wells constructed under LANL’s Hydrogeologic Workplan (LANL, 1998). The allegations were that “(1) the use of mud rotary drilling methods violated RCRA; and (2) the use of muds and other drilling fluids during well construction had an adverse effect on groundwater chemistry, masking the presence of radionuclides and causing groundwater contamination data to be unreliable” (DOE, 2005, p. 2). The IG found that these allegations were partially substantiated.

LANL responded to the IG’s findings with a Well Screen Analysis Report (LANL, 2005a). In that report LANL analyzed the effects of residual drilling fluids on samples taken from groundwater wells in the regional aquifer and evaluated the ability of these wells to provide representative measurements. A review of LANL’s report by the EPA, however, found that:

In general, the criteria used to evaluate the representativeness of groundwater samples installed under the hydrologic characterization program still fail [italics added] to consider impacts that may be present following biodegradation of residual organic drilling additives and the return of oxidizing conditions. (Ford and Acree, 2006, p. 1)

The EPA report also presented nine other concerns regarding LANL’s well screen analysis.

STATUS OF THIS STUDY

This status report was written at approximately the halfway point in the committee’s study. A total of six meetings were provided in the study’s schedule. Three open-session meetings have been held in the Los Alamos/Santa Fe region of New Mexico, essentially completing all of the committee’s planned information-gathering activities. The three remaining meetings will allow the committee to develop its findings and recommendations and prepare its final report.

The committee was well supported in its information gathering by LANL scientists and other stakeholders who made presentations and participated in discussions during the meetings (meeting presentations are given in Appendix A). Mat Johansen of the NNSA Albuquerque Operations Office served as the committee’s point of contact with DOE. Jean Dewart and Donathan Krier of the LANL Environmental Programs Directorate were especially helpful, respectively, in serving as the committee’s point of contact with LANL and fulfilling the committee’s many document requests.

The committee held its first meeting on March 23-24, 2006, in Santa Fe to gain a basic overview and understanding of LANL’s operating history, history of waste

discharges, geology and hydrology, and the site’s technical programs for dealing with issues to be addressed by the committee. Accordingly, most presentations were made by LANL personnel. The committee also requested and received overview presentations from the Pueblo de San Ildefonso, the Northern New Mexico Citizens’ Advisory Board (NNMCAB), and NMED. As in all of its information-gathering meetings, time was provided for comments from all attendees.

The committee’s second meeting, May 16-17, 2006, in Santa Fe and Los Alamos, emphasized non-LANL presentations. Robert Gilkeson, a registered geologist and former LANL adviser and contractor, gave a technical critique of the LANL monitoring program. James Bearzi, Chief of the NMED Hazardous Waste Bureau, gave an overview of the Consent Order and summarized LANL groundwater issues of regulatory significance. The second day of the meeting included a visit to the Pueblo de San Ildefonso, an overview tour of portions of the LANL site, and participation in an NNMCAB Groundwater Forum meeting at the Smith Auditorium in Los Alamos. At the Forum, committee chairman Larry W. Lake described the committee’s task statement and plans for conducting its study.

The committee members chose a workshop format for their third meeting, held August 14-15, 2006, in Santa Fe. The main purpose of the workshop was to conduct detailed technical discussions with LANL scientists and others to address questions developed by committee members.

Workshop Plenary Session

The term “groundwater protection” is prominent in the committee’s task statement. During the closed session wrap-up of the second meeting, several members raised the question of what exactly is meant by the term. It appeared that DOE, its regulators, and public stakeholders had different views of what would constitute groundwater protection at LANL.

Accordingly, for the workshop the committee organized part of its plenary session around the questions: “What constitutes groundwater protection?” and “What should be the objectives of LANL’s groundwater protection program?” Representatives from six organizations were invited to give five- to seven-minute commentaries on these questions and then participate in a question and answer session, which was open to all attendees. Invited organizations were selected by the committee to reflect a variety of viewpoints, based on their participation in the earlier meetings and advice from the NNMCAB. The viewpoints presented are summarized in Sidebar 3.

The committee will consider these views on groundwater protection in approaching its task statement for the final report. More importantly, the committee hopes that further discussion of these fundamental questions by LANL, its regulators, and public stakeholders will help promote agreement on what LANL’s groundwater protection program should accomplish.

|

Sidebar 3 Stakeholder Perspectives on Groundwater Protection Concerned Citizens for Nuclear Safety (CCNS) Groundwater protection is very basic and simple. It means:

Department of Energy-National Nuclear Security Agency (DOE-NNSA) Groundwater protection is achieved by meeting specific requirements that are spelled out in:

DOE requires maintaining groundwater quality adequate for its highest beneficial use, which DOE considers to be extraction of drinking water from the regional aquifer. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) EPA’s standards and policies for groundwater protection include the following:

New Mexico Environment Department (NMED) What constitutes groundwater protection at LANL is specified in the:

|

|

According to both the WQCC regulations and the Consent Order, “groundwater” means interstitial water that occurs in saturated earth material and which is capable of entering a well in sufficient amounts to be used as a water supply. The WQCC regulations include the notion of groundwater that can be “reasonably expected to be used in the future” and states that risk from a toxic pollutant must not exceed one cancer per 100,000 exposed persons. The Consent Order requires cleanup of groundwater when the lower of either WQCC standards or EPA maximium contaminant levels (MCLs) are exceeded. Northern New Mexico Citizens’ Advisory Board (NNMCAB) Contamination at LANL arose in the context of ensuring the nation’s nuclear security. Similar commitment and continuity in monitoring and site remediation is required, including:

Pueblo de San Ildefonso Land, air, and water are sacred. They must be viewed holistically, so that groundwater cannot be separated from the others. LANL occupies the ancestral domain of San Ildefonso.

Los Alamos National Laboratory LANL summarized its goals for groundwater protection during the opening session of the plenary, as follow (Dewart, 2006):

|

Workshop Breakout Sessions

To ensure that members’ technical questions were addressed in detail, the committee organized breakout sessions on three simultaneous tracks. Three committee members led each session, and five to ten LANL scientists and other interested individuals participated in each. During the sessions, committee members heard real and useful interactions among all participants.

The three tracks for the workshop were:

-

Sources of contamination: location, inventory, and controls;

-

Flowpaths for contaminant migration in vadose and saturated zones, and their conceptual models; and

-

Groundwater monitoring and data quality.

While recognizing that the topics of the breakout sessions are interconnected, committee members decided that organizing their technical discussions in these three tracks would be most efficient for gathering information to address the task statement, as described below.

Track 1 focused on LANL’s understanding of potential sources of groundwater contamination. The discussions addressed two subtopics of the statement of task:

What is the state of the laboratory’s understanding of the major sources of groundwater contamination originating from laboratory operations and have technically sound measures to control them been implemented?

Have potential sources of non-laboratory groundwater contamination been identified? Have the potential impacts of this contamination on corrective-action decision making been assessed?

Track 2 focused on LANL’s understanding of flowpaths that could transport contaminants from sources to the regional groundwater and ultimately to receptors. Two subtopics of the statement of task are directly related to how well flowpaths are understood:

Does the laboratory’s interim groundwater monitoring plan follow good scientific practices? Is it adequate to provide for the early identification and response to potential environmental impacts from the laboratory?

Is the scope of groundwater monitoring at the laboratory sufficient to provide data needed for remediation decision making? If not, what data gaps remain, and how can they be filled?

Track 3 focused on data-quality issues related to judging the adequacy of LANL’s groundwater monitoring program and future plans. The discussions addressed the data-quality issues in the statement of task:

Is the laboratory following established scientific practices in assessing the

quality of its groundwater monitoring data?

Are the data (including qualifiers that describe data precision, accuracy, detection limits, and other items that aid correct interpretation and use of the data) being used appropriately in the laboratory’s remediation decision making?

Discussing, comparing, and evaluating information gained in the breakouts will be a major part of the committee’s work in developing its final report.

SUMMARY OF TECHNICAL INFORMATION PRESENTED TO THE COMMITTEE

During the information-gathering portion of this study, the committee received approximately 60 reports and other written materials and heard some 25 presentations. In addition, the workshop provided eight hours of focused scientific and technical discussions. The following is a general overview of the information received. The committee does not intend this to be a full summary of the information that it will consider for its final report, nor does it reflect any assessment of the accuracy of information received.

Sources of Contamination and Source Controls

LANL is systematically investigating contaminant sources (principally liquid waste discharges and buried waste) and the nature and extent of releases under a prioritized sequence that is consistent with the Consent Order. There are uncertainties in the total amount of contaminants that were historically discharged at the site. As of October 2006 LANL had not begun groundwater remediation under the Consent Order’s regulatory compliance requirements (Dewart, 2006).

Contaminant movement from its source to groundwater (or in groundwater, see the section on flowpaths) is determined by the chemical properties of the contaminant. LANL uses the terms “conservative” and “non-reactive” to describe contaminants that do not sorb readily onto soils or other media and therefore can move at about the same velocity as the water (i.e., they are mobile). Examples include tritium (as tritiated water), perchlorate, nitrate, chromium (as the chromate anion CrO42-), and high explosives (e.g., RDX).2 Sorbing or “reactive” species are much less mobile, and largely remain near their source. Examples of sorbing radionuclides include strontium-90, cesium-137, and plutonium.

Transport of sorbing species by water can occur, however. Stormwater runoff and erosion after the Cerro Grande fire in spring 2000 moved considerable amounts soil and other materials, including contaminants, toward the Pueblo de San Ildefonso and the Rio Grande River (Alvarez and Arends, 2000; LANL, 2005b). Transport of plutonium

colloids or plutonium sorbed onto colloids3 has been discussed in the literature to explain unexpectedly long distances of plutonium migration at DOE sites, including Los Alamos and the Nevada Test Site, and around the Mayak site in Russia (Penrose et al., 1990; Kersting et al., 1999; Novikov et al., 2006).

Uranium is associated with trace minerals that occur naturally in the Los Alamos region. These minerals (zircon and apatite) have a low aqueous solubility, which results in uranium concentrations of less than about 1 part per billion (ppb) in groundwater beneath some regions of LANL. Uranium from laboratory activities from 1943 to the mid-1950s is also present and has migrated to perched intermediate zones and the regional aquifer (see Figure 2). This laboratory-origin uranium typically is at concentrations somewhat higher than 1 ppb. LANL noted that uranium is one example of a complicated case in which statistical methods coupled with knowledge of releases and co-occurrences of other mobile contaminants may be needed before a confident identification of the source of some contaminants can be made (Simmons, 2006a).

According to LANL (Dewart, 2006; Katzman, 2006), the potential for a source of contamination to affect deep groundwater is governed predominantly by:

-

Size of the inventory;

-

Mobility of the chemical form of the contaminant;

-

Presence of an aqueous driver; and

-

Subsurface stratigraphy.

Major LANL contaminant impacts on groundwater are the result of large volumes of liquid effluents released in the past. In addition to being sources of contaminants, the effluent releases increased infiltration (Rogers, 2006a). The liquid discharges that LANL considers to be significant sources of groundwater contamination are listed in Table 1 (Katzman, 2006).

Since 1994, LANL has reduced the number of locations where liquid waste is released to the environment from 141 to 21. The Radioactive Liquid Waste Treatment Facility in TA-50, which has operated since 1963, has been the only source of radioactive liquid discharges since 1986 (Rogers, 2006b). LANL presented data showing that ceasing the other discharges resulted in rapid improvement in alluvial groundwater quality for non-sorbing contaminants, as the contaminated water moved downward out of the alluvium (Rogers, 2006a). LANL indicated that alluvial water quality for the sorbing contaminants is improving more slowly (Rogers, 2006a).

There are 25 locations where solid waste has been disposed of, referred to as material disposal areas (MDAs), across the site.4 The MDAs include large buried-contaminant inventories with some mobile constituents. However, they are located on dry mesa tops with little or no continuous water influx. LANL considers these MDAs less important sources than liquid outfalls. In discussions, however, NMED and other stakeholders expressed concern that ponding of rainwater in the disposal pits while they are open could provide an aqueous driver for contaminants released from the solid

TABLE 1 LANL’s Current View of Liquid Releases That Are the Key Sources of Deep Groundwater Contamination

|

Source |

Location (see Figure 1) |

Operation |

Period of Operation |

Constituents Detected in Deep Groundwater |

|

Radioactive Liquid waste Treatment Facility in Technical Area 45 (TA-45) |

Pueblo Canyon |

Radioactive waste treatment |

1944-1964 |

tritium, perchlorate |

|

Omega West Reactor (reactor leak) |

upper Los Alamos Canyon |

Research and isotope production |

ca. 1970-1993 |

tritium |

|

Radioactive liquid waste effluent |

Los Alamos Canyon |

Industrial wastewater outfall |

1952-1986 |

tritium, perchlorate, nitrate |

|

Power plant cooling tower blowdown (TA-3) |

Sandia Canyon |

Corrosion inhibitor |

ca. 1950-1972 |

chromium |

|

High explosives machining outfall |

Cañon de Valle |

High explosive machining |

1951-1996 |

high explosives, volatile organic compounds(?) |

|

Radioactive Liquid Waste Treatment Facility (TA-50) |

Mortandad Canyon |

Radioactive wastewater treatment |

1963-present |

tritium, nitrate, perchlorate |

|

Los Alamos County Bayo Wastewater Treatment Plant |

Pueblo Canyon |

Sanitary wastewater treatment |

1963-present |

nitrate, others(?) |

|

Canyon sediment and alluvial groundwater |

Secondary sources |

NA |

Variable |

tritium, nitrate, perchlorate, chromium, high explosives, volatile organic compounds |

|

Source: Katzman (2006) |

||||

wastes. MDAs are being investigated through 2010 with corrective actions scheduled through 2015 under the Consent Order (Katzman, 2006).

The following highlights the workshop discussion on sources and source control:

-

Birdsell et al. (2006) provided a summary report “Selected Key Liquid-Outfall Contamination Sources from LANL.”

-

The Birdsell et al. report was limited to mobile sources (tritium, perchlorate, nitrate, chromium). It did not include actinides or other contaminants that LANL considers to be practically immobile.

-

Besides these specific “anthropogenic liquid ” sources, many other potential sources of groundwater contamination exist,but their characterization is not as advanced yet.

-

Mortandad Canyon is probably the best characterized area on the site. Therefore, it may provide a template for the type and extent of characterization that LANL seeks for other areas.

-

Using Mortandad Canyon as an example, Birdsell et al. include a three-dimensional diagram showing that most of the mass of perchlorate now resides between the canyon alluvium and the regional groundwater.

-

The site has many “solid waste management units ” (SWMUs) that are presumed to be small.5 They may not be fully explored at this time.

-

Erosion after the Cerro Grande fire affected transport of contaminants present at and near the surface.

Flowpaths for Contaminant Migration

LANL considers that regional aquifer pathways are well understood at the basin and plateau scales, but predictions at the scale of individual contaminant sources are complicated by small-scale heterogeneities and anisotopy in the rock permeability. Heterogeneity refers to the general variability in the geological media, while anisotropy in the rock permeability may create a preferred direction for water movement. According to LANL, these effects, combined with the influence fo municipal water supply well pumping, lead to significant uncertainty in flow path predictions at the local scale. Alluvial groundwater is a rapid lateral transport pathway for non-sorbing contaminants (Robinson, 2006).

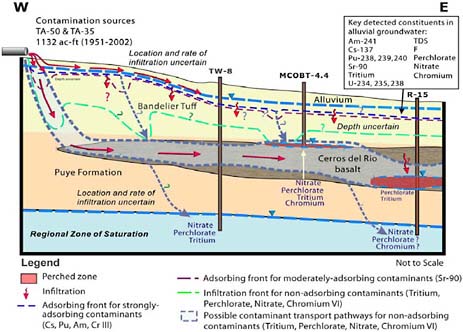

Mortandad Canyon has been a priority for groundwater investigations because it has continued to receive discharges from the site’s Radioactive Liquid Waste Treatment Facility since 1963. Most of LANL’s presentations on groundwater hydrology and groundwater conceptual modeling dealt with this canyon, which is illustrated in Figure 3.

Source: Donathan Krier, LANL

FIGURE 3 Mortandad Canyon Hydrogeologic and Contaminant Conceptual Model. LANL considers this canyon to be a significant source of groundwater contamination. Much scientific effort has been focused on understanding its hydrology.

According to LANL (Newman and Birdsell, 2006; Robinson, 2006), travel times to the regional aquifer from surface sources are a function of two factors: infiltration rate and hydrogeology.

-

Travel times are in excess of 1000 years from mesas. In these areas downward percolation rates are typically <10 mm/yr, and few perched water bodies have been found.

-

Travel times are on the order of decades in canyons where there is water from natural, municipal, or LANL discharges. In these “wet canyons,” downward percolation rates can be on the order of 1000 mm/yr.

-

There is slow percolation of water through the Bandelier Tuff.

-

Fractured basalts may provide fast vertical and horizontal pathways throug the vadose zone, with the potential to cause perched groundwater to move in

-

unpredictable directions from beneath the wet canyons where infiltration originally occurred.

In the regional aquifer, groundwater flow is generally from west to east toward the Rio Grande. The aquifer contains waters of very different ages. Based on carbon-14 dating, some of the water is over 1000 years old. Tritium data show that there is also a component of very young water (<45 years). Water in the aquifer generally increases in age from west to east, and the deepest groundwaters typically show no indication of anthropogenic influence (Robinson, 2006).

Highlights of the workshop discussion on flowpaths included the following:

-

The major liquid and solid waste sites and how well the LANL scientists believe they understand the movement of contaminants from these sites;

-

The major flowpath conceptualizations for each of the major sources and how well the LANL scientists believe they understand the flowpaths;

-

Numerical models of the vadose zone and regional aquifer and how well these models compare to the existing flow conceptualizations;

-

Multi-phase simulations of water and vapor at one of the mesa-top disposal sites;

-

Regional flow models and their use in evaluating the effectiveness of the existing groundwater monitoring system;

-

The difficulty in interpreting aquifer test data for characterizing anisotropy and heterogeneities;

-

Methods and utility of incorporating uncertainty into an analysis of contaminant transport;

-

Long-term stewardship discussions, with LANL staff noting that plans for long-term stewardship are still in the developmental stages; and

-

Remedial action plans for chromium in the groundwater.

Monitoring and Data Quality

The U.S. Geological Survey began monitoring of water supply wells, observation wells, and springs around the Los Alamos site in 1949. A court decision in 1984 extended RCRA to DOE’s chemically hazardous waste, and later that year the Hazardous Waste Amendments to RCRA further increased the stringency of RCRA requirements at DOE sites. In 1986 EPA clarified its jurisdiction for mixed waste (waste that contains both chemically hazardous and radioactive constituents) and determined that states must include mixed waste in RCRA authorizations.6

LANL received an EPA/NMED operating permit in 1989, which required monitoring of RCRA-regulated facilities. In 1995 NMED found LANL’s groundwater characterization program to be inadequate and denied LANL a waiver from its groundwater monitoring requirements. Subsequently, LANL developed a Hydrogeologic Workplan (LANL, 1998) to refine its understanding of the site’s hydrogeology in order to design an effective monitoring network. NMED approved the workplan in 1998.

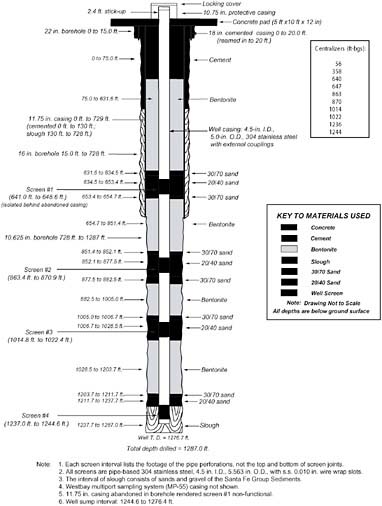

Prior to the workplan LANL had seven regional aquifer wells, two deep borings, and two intermediate depth wells. By 2006 LANL had added 35 new regional aquifer wells and approximately 22 new intermediate-depth boreholes and wells (Broxton, 2006). Figure 4 illustrates a multi-screened water well as installed at the LANL site. Note that the well screens are the places where groundwater can enter the well; hence, the screens are the sampling points in each well.

Source: Donathan Krier, LANL

FIGURE 4 Diagram of a Multi-Screened Well. The well screens are locations at which groundwater can enter the well. Waters sampled from these screens are required to be representative of the native (unperturbed) groundwater in the formations surrounding the screened interval.

In presentations to the committee LANL distinguished between “characterization” for the purposes of gaining basic knowledge and understanding, versus “monitoring”— surveillance of groundwater quality to ensure compliance with regulatory requirements Under the workplan, groundwater wells were drilled into the regional aquifer to characterize both its hydrogeologic properties and characterize its contamination. However, drilling such wells is expensive (some $1 million to 2 million each), so LANL has sought in a number of instances to use the same wells for both characterization and monitoring (Broxton, 2006).

LANL emphasized that well design, drilling methods, and well development— particularly for the approximately 1000-foot-deep wells that reach the regional aquifer— are evolving. This is especially true for well development, which is the part of the well-construction process intended to remove drilling fluids and repair damage done to the formation adjacent to the borehole wall by the well drilling. For monitoring wells, the goal is to restore the properties of the original formation, especially with respect to chemical conditions, porosity, and permeability (Broxton, 2006).

An expert advisory group (EAG) convened by LANL to assess its well drilling program concluded that challenges to well development are the following (Anderson et al., 2005):

-

The wells are deep.

-

The wells are small in diameter.

-

The static water levels are deep.

-

Some of the aquifer formations are tight (i.e., of low permeability) and yield little water.

-

Multiple zones have substantially different piezometric heads.

Given these difficulties, the EAG concluded:

There is not one single approach that is guaranteed to produce ideal results….it likely will not be feasible to develop individual screen zones to “near perfect” conditions, as it might be possible in a large diameter, shallow well in a permeable aquifer with a high static water level. However,…it should be possible to obtain acceptable well development and reasonable results (Anderson, et al., 2005; as presented by Broxton, 2006).

Following the DOE inspector general’s report (DOE, 2005), LANL undertook an analysis of the impacts of residual drilling fluids on the ability of the groundwater wells in the regional aquifer to provide representative measurements. Its purpose was to:

-

Evaluate whether the well screens are producing data that are reliable and representative of the intermediate groundwater and regional aquifer;

-

Provide a summary of the number of well screens that are producing reliable data and the number that are potentially impacted; and

-

Of the impacted screens, identify those that appear to be cleaning up over time and those that are the most problematic (Simmons, 2006b).

|

Sidebar 4 LANL’s Approach to Assessing the Quality of Data from Selected Well Screens

Sources: LANL (2005a); Simmons (2006b). |

This Well Screen Analysis (LANL, 2005a) included 64 screens in 33 wells. It included effects of bentonite drilling mud (12 screens in 9 wells) and organic polymer-based additives to drilling fluids in all 64 screens (Simmons, 2006b). The approach LANL took in performing its analysis is summarized in Sidebar 4.

According to LANL’s analysis, a third of the well screens provide very good chemical data. Single-screen wells show the least impact from residual drilling fluids. All 16 single-screen wells were rated good to very good according to LANL’s assessment criteria. The majority of screens in multi-screened wells are impacted by residual drilling fluids. However, in many cases LANL would prefer to redevelop the existing wells that are not producing reliable data rather than to drill new wells, which LANL considers to be a more expensive option (Simmons, 2006b).

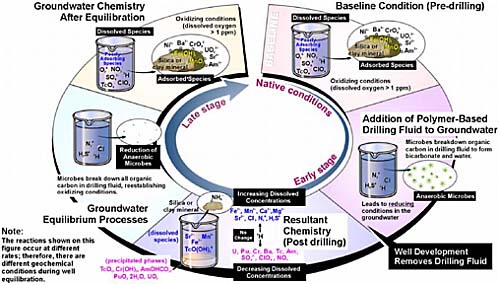

LANL acknowledged that bentonite drilling mud may be a source of inorganic salts and may sorb some metals, radionuclides, and organic species. Organic polymer additives used in drilling fluids may cause any or all of the following: (1) change the chemical reduction/oxidation (redox) environment around the screens, which may alter some of the chemical species that are being analyzed for in the groundwater; (2) dissolve some minerals and release adsorbed metals; and (3) provide a nutrient media for microbial growth (Simmons, 2006b). LANL’s view of the possible effects of organic polymer additives on groundwater chemistry is depicted in Figure 5.

What LANL refers to as “interim monitoring” started in 2006. The current system of monitoring is considered interim because site characterization is not complete as defined in the Consent Order. Further, LANL agrees that some characterization wells may not be suitable for monitoring. LANL’s goal, as prescribed by the Consent Order, is to transition to long-term groundwater monitoring in all watersheds throughout the site by 2015 (Dewart, 2006).

Source: Donathan Krier, LANL

FIGURE 5 Possible Effects of Drilling Fluids that Contain Organic-Polymer Additives. If these drilling fluids are not throughly removed from a monitoring well during its development, their biodegradation could affect the reduction/oxidation (redox) conditions of groundwater near the well screens. LANL believes that such an effect would be temporary so that the system would eventually return to its native (undisturbed) condition. Others disagree.

Robert Gilkeson made technical presentations to the committee that were generally critical of LANL’s groundwater program. He found that previous failures and deficiencies in the program, such as those that led to the DOE inspector general’s report, are being repeated, and he called for “independent validation and verification of LANL activities” by a company that is independent of DOE and approved by stakeholders (Gilkeson, 2006a).

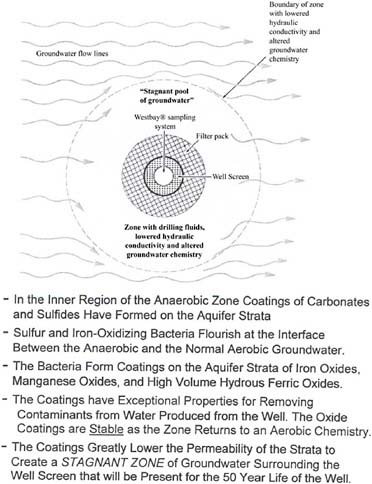

In his presentation at the committee’s second meeting, Mr. Gilkeson stated that bentonite clay and/or organic drilling additives had invaded the screened intervals in all of the LANL characterization wells. He illustrated (see Figure 6) how these materials can set up a reactive capture barrier that tends to remove contaminants from sampled groundwater, which would preclude use of the well for monitoring. He concluded that well development efforts are unlikely to be effective for removing this barrier. Mr.

Source: Gilkeson (2006a); also see Ford and Acree (2006)

FIGURE 6 Reactive Contaminant Capture Barrier that Surrounds the Screened Intervals in the LANL Characterization Wells. Geologist Robert Gilkeson described how drilling fluids could form a zone that removes contaminants from sampled groundwater. This would invalidate affected well screens as sampling points.

Gilkeson disagrees with LANL’s view that natural processes can restore groundwater chemistry to its initial conditions after those conditions have been disturbed by organic drilling fluid additives (see Figure 5; also see Ford and Acree, 2006).

Mr. Gilkeson also noted that some installed wells are located relatively far from the contamination sources they would be intended to monitor (e.g., buried waste disposal at MDA G and MDA L). He singled out wells R-16, 20, 26, and 34 as not useful for

monitoring.7 He stated that some wells (e.g., R-15, 22, 25, 26) have cross-contaminated aquifers (Gilkeson, 2006a).

In his presentation at the committee’s workshop, Mr. Gilkeson provided a summary of his reasons that many of LANL’s wells that penetrate the regional aquifer and some perched aquifers do not produce reliable and representative water quality data:

-

Drilling additives;

-

Corrosion of iron well screens in the older wells;

-

Construction errors that have plugged screens with bentonite clay;

-

Dilution of contamination by very long well screens;

-

Well screens in strata with low permeability rather than in strata with high permeability; and

-

Well screens too deep below the water table of the regional aquifer.

As one case in point, Mr. Gilkeson described problems with well R-21, which the Well Screen Analysis report rated as “very good” in producing reliable and representative water samples. He noted the well is 1200 feet from Area L, which it is intended to monitor, whereas compliance with RCRA Subpart F would require a cluster of monitoring wells directly along the downgradient boundary of buried waste in Area L. Further, he noted that the top of the 20-foot-long screen in well R-21 is located 87 feet below the water table, whereas RCRA Subpart F requires that well screens be no longer than 10 feet and be located in permeable strata near the water table (Gilkeson, 2006b).

Highlights of the workshop discussions on monitoring and data quality included the following:

-

The continuing evolution of processes for monitoring and establishing the quality of the data;

-

Impetus to the current monitoring program by the Consent Order and other requirements;

-

Monitoring to protect supply wells and to provide data for model validation and connection to sources;

-

Issues with analytical data quality from previous and current sampling activities (legacy sampling) as well as with proposals for future monitoring,

-

Monitoring for long-term stewardship and remediation under the Consent Order—including methods to identify additional well locations for within-canyon characterization and methods to develop site-wide plans, and application of innovative technologies used or developed at other DOE facilities; and

-

The need for decision-making processes that include all stakeholders.

FUTURE PLANS FOR THIS STUDY

The committee’s information gathering is substantially completed. The remaining study period and meetings will be used primarily for deliberation, developing consensus on the findings and recommendations requested in the task statement, and producing the final report. According to National Academies’ practices, the committee’s conclusions and recommendations will be available only after the draft report has completed Academies review and the finalized draft has been approved for public release, which is scheduled for May 2007.