4

Cadastral Survey Requirements and the Cadastral Overlay

A basic component of the multipurpose cadastre is a cadastral overlay delimiting the current status of property ownership. The individual building block for the overlay is the cadastral parcel, an unambiguously defined unit of land within which unique property interests are recognized. The overlay will consist of a series of maps showing the size, shape, and location of all cadastral parcels within a given jurisdiction.

Cartographically, the cadastral maps should be viewed as overlays to the large-scale base maps. However, the term “overlay” does not imply that the relationship between the cadastral maps and the base maps is defined by the coincidence of their graphic plots. Rather, the cadastral boundaries are lines connecting points that have unique identities and records, through which they may be located on the ground. Accurate placement of these points on the cadastral overlay does not improve the accuracy of the definition of the boundary, which must be documented elsewhere. The purpose of accurate plotting is simply to make the maps themselves more useful and easier to maintain.

There are several legal mechanisms for establishing cadastral overlay standards, mechanisms that also impart a legal and institutional stability to the cadastral overlay. These mechanisms include (1) land subdivision laws that require surveying, mapping, and recordation according to prescribed standards; (2) regulation of legal parcel descriptions and associated field work by statute as well as by common law; (3) recordation of as-built plans; (4) administrative regulations issued by the courts that register property boundaries in certain states (notably Massachusetts and Hawaii); (5) designation of integrated survey areas; and (6) greater use of the official map in connection with the master plan. The official map is a long-used device (Beuscher and Wright, 1969) that is described in Appendix A.1.

In counties where the delineations of property boundaries by field surveys must be approved by a public office. as in the state of California, it may be possible for the cadastral overlay (including the supporting numerical records based on field surveys) to be tied directly to the legal documents that define the property boundaries. as they are in the cadastres of Continental Europe. This type of public register of property boundaries now occurs in two counties in Massachusetts where registration of both title and boundary includes about half of all parcels.

4.1

CREATION AND MAINTENANCE OF CADASTRAL OVERLAYS

The development of a cadastral overlay will consist of a series of integrated operations, entailing the compilation of land-tenure information and the publication of cadastral maps. Ideally, an area will be chosen for implementing the cadastral-mapping program within which the geodetic reference framework and the large-scale base-mapping program have been established.

There may be a temptation to initiate the cadastral overlay program before an adequate base map is available. The cadastral map is a highly valuable, tangible product that can garner public recognition and support for a multipurpose cadastre initiative. Furthermore, the land-tenure overlays are an invaluable tool in developing other aspects of the cadastral program. However, such a shortcut to a cadastral map should be discouraged, for experience has shown the following:

-

It is often difficult subsequently to transfer the parcel information to the higher-quality, uniform large-scale mapping base; and

-

There is always the danger that the product may be misused with a resulting loss in consumer confidence (McLaughlin, 1975).

Another important prerequisite for a cadastral mapping program is a budget for continuing maintenance of the maps. The front-end investments in improved cadastral maps will be wasted if insufficient resources are allocated for keeping them constantly up to date. The annual cost of the technical personnel needed for this work may average more than 5 percent of the original cost of the maps. Howwver, most of the counties that have invested in the elaborate type of digital map system described in Section 3.5.3 have found their costs of map maintenance to be substantially reduced.

We recommend that the updating of cadastral overlays be scheduled so as to assure that they will reliably show any new or changed land parcels that have been in existence for two weeks or more. Where the overlays are used by the recorder of deeds to display the parcel numbers used for indexing the land-title records, this updating should occur within one week.

4.1.1

Comprehensive versus Iterative Mapping Programs

The land-tenure information initially obtained for the development of the cadastralmapping program will undoubtedly be of mixed quality. Recorded subdivision plans may be available for some areas. For others perhaps only rudimentary deed descriptions will be available. There are two very different approaches to overcoming this difficulty:

-

Development of a comprehensive survey program designed to establish the bounds of all parcels in advance of the cadastral mapping program and

-

Development of an iterative mapping program based initially on the existing information base but improved over a period of time as higher-quality information becomes available.

A comprehensive survey program designed to establish the bounds of all cadastral parcels within a jurisdiction has its attractions. The information provided by such a program would presumably be of the highest possible quality with respect to both spatial accuracy and the depiction of all appropriate parcel evidence (particularly possessory evidence in jurisdictions where legally recognized). However, the total economic and human resources, together with the time required to accomplish such a monumental undertaking, often will prove prohibitive. The range of costs may be anywhere from $5 to $50 per parcel or more. depending on such factors as (1) the sizes of the parcels. (2) the quality of the base map, (3) the quality of previous local surveys and their records, (4) whether property corners must be located with typical accuracies of 1–2 ft in rural areas or 0.1 ft in urban areas, and (5) the proportion of costs being assigned to the cadastral overlay.

The only realistic course of action may be to implement the cadastral overlay program in an iterative manner, initially using existing information resources. The minimum requirement for this process is that all parcels must be accounted for, and there must be a capability of correlating the overlay to the base maps.

To support the continuing improvement of local cadastral survey records, we reiterate the recommendations in Section 3.5.4 of the report of the Committee on Geodesy (1980) that

-

Lawyers and surveyors promote state legislation that would make the recording of survey plans for conveyance or subdivision mandatory; all new deeds be based on a reliable survey, similar to those required by the plat laws or sectioncorner filing acts that exist in some states; and the American Congress on Surveying and Mapping and the American Society of Civil Engineers propose model standards.

-

Title insurance companies agree that all future policies be accompanied by a survey plat or plan; and the American Land Title Association and the American Bar Association propose model standards.

-

All title insurance surveys be recorded for the benefit of abutters and future

-

users; and the American Bar Association and the American Land Title Association propose model standards.

-

All boundary-survey plans show deed references of land owners and adjacent land owners until a parcel-identifier system has been adopted.

4.1.2

Sequence of Tasks

The first task in preparing the cadastral overlay will be to establish the quality of the existing information and, where information discontinuities exist, to carry out supplemental surveys. This task should be placed under the direction of an experienced land surveyor, well versed in the peculiar nuances of the law and practice of surveying in the region. The compilation of this information will consist of the creation of a hierarchical graphical framework, holding the more highly weighted information fixed and fitting the lower-weighted information to it. Although the weighting of evidence will depend in part on the law and practice of surveying as specifically related to the region, in general it will follow the broad categories as listed in descending order below (McLaughlin, 1975):

-

Natural boundaries as plotted on the base maps (such as lakes, rivers, and roads) will generally form the highest-weighted information framework:

-

Geodetically referenced cadastral surveys that can be plotted on the base maps will provide the next highest weighted information;

-

Monument referenced cadastral surveys will then be fitted to the framework;

-

Physical evidence of original surveys (such as old rural fences) will next be fitted to the framework;

-

Deed descriptions (which in many areas will form the bulk of the existing information) will then be fitted to either natural boundaries or to survey measurements; and

-

A final category of information to be fitted will include deeds that merely describe abuttals, assessors’ descriptions, and other similar information.

The ranking of deed descriptions below physical evidence of older surveys is based on the widely accepted legal surveying principle that the boundary as acknowledged and adhered to by contiguous landholders should have legal precedence over mathematical descriptions.

The above broad listing of categories for weighting information must necessarily be tempered by considerations of the time during which the information was first collected, the techniques and instruments used to collect the information, and corrections that have or have not been made to the information, such as the correction from magnetic to grid orientation. It is because of these considerations that the services of a professional land surveyor will be required during the compilation tasks.

Once an interim parcel base has been compiled, parcel identifiers will be assigned

to each parcel. The assignment and control of these identifiers is described below. Subsequently, both the parcel locations and the assigned identifiers must be checked to ensure that

-

All cadastral parcels within the jurisdiction have been accounted for;

-

The best available information has been employed to determine the approximate size, shape, and location of each parcel;

-

The correct parcel identifier has been assigned to each parcel; and

-

Indexes are available that facilitate future access to all the documents used to locate and describe property corners and monuments shown on the maps, i.e., that the documentation is keyed to parcel identifiers. point identifiers, or some other references that appear on the maps.

While all aspects of the checking operation will be important, particular attention must be focused on ensuring that all parcels are accounted for. Only in this manner can the subsequent iterative operations be carried out reliably. Usually, the best available tool for accomplishing this task in most jurisdictions will be the current assessment record. However, experience has shown that as many as 20 percent of the parcels compiled in a cadastral overlay program may never have been shown on the assessment record. If any uncertainties are uncovered during the checking operation, the draft parcel map should be routed back to the compilers. In some instances, additional field surveys may be required.

On completion of the checking process, the overlay can then be published as part of the cadastral-mapping series. At this stage, the interim sheet should carry the date of compilation and should note that “The compiled parcel information is of a provisional nature only and must not be used for legal purposes.” This declaration is necessary to ensure that this interim mapping product, which is based on information of mixed quality, is not misused. Once a cadastral survey program is implemented, the means of providing for the continuous updating and improvement of the overlay series will be available and the provisional declaration may be dropped.

4.2

CADASTRAL SURVEY REQUIREMENTS

The effective maintenance of a series of cadastral maps and, indeed, the successful implementation of a multipurpose cadastre, will be dependent in large measure on the quality of the cadastral survey system.

4.2.1

Scope of Standards Required

A cadastral survey system governs the creation and mutation of parcel boundaries. The system also maintains both microlevel and macrolevel spatial records of current

land-tenure arrangements. The functions of a cadastral survey system will be defined in one or more surveying and boundaries statutes and in regulations pursuant to these statutes. In a comprehensive system, statutory authority will specify

-

The geometric reference framework to which all information must be referred,

-

The type and weighting of information that must be provided in evidence of the creation or mutation of a boundary,

-

The standards of survey practice that must be met in providing this information,

-

The authority vested in a public survey administrator to examine and register proposed boundary mutations, and

-

The right of judicial appeal from administrative decisions.

In any jurisdiction introducing the multipurpose cadastre concept, boundaries should be recorded within the cadastral survey system to be legally effective. Furthermore, any statute that relates to the creation or mutation of parcel boundaries, such as subdivision, expropriation, quieting of titles, highway alignment, and similar legislation, should make reference to the examination and registration requirements of the cadastral survey system.

Standards for cadastral surveys may be formulated with respect to identifiers for all boundary points, monumentation (materials, dimension, reference points), information required on monuments (surveyor’s name, monument number, dates), spatial accuracy of location data, data required in the record of each boundary segment (identities of end points and identities of parcels bounded), plans or plats of survey (seals, detail, cartography, approvals, materials), field books, and oaths. In this section, however, we will restrict our discussion to spatial accuracy considerations.

The legal surveying component of the cadastral survey system generally entails the two-phase operation of (a) gathering, interpreting, and weighting pertinent information and (b) spatially referencing the information. Accuracy specifications are necessary for both of these phases. There is always the danger that while analyzing the accuracy of spatial referencing the importance of accurately interpreting the boundary evidence itself will be overlooked. For example, spatial referencing may appear to relocate a boundary within a tolerance of 0.01 ft (based on an analysis of the measurements), where, in fact, because of a misinterpretation of the evidence, the boundary may be displaced several feet.

4.2.2

Accuracy of Position

Boundaries may be described by points or corners, straight lines, and/or curvilinear lines. Accuracy specifications may be expressed in terms of traverse misclosures or boundary tolerances. Of these the boundary tolerance is a far superior, if somewhat more complex, approach that is illustrated in the following cadastral relocation ex-

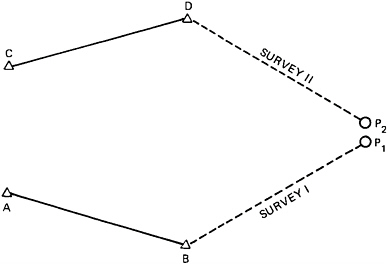

ample (McLaughlin, 1977). In this example two cases can be described (see Figure 4.1):

-

Point P was originally coordinated and marked in the location P1 by Survey I connected to control points A and B. Later, Survey II, connected to control points C and D, was requested in order to relocate point P in its original location corresponding to the coordinates of point P1. Owing to the accumulation of random errors, Survey II determined that point P should be located at P2. The question then becomes What maximum distance (maximum relocation error) between P1 and P2 may be expected at a given confidence level?

-

The same point P, marked on the ground, was independently coordinated by Survey I and Survey II. Owing to the accumulalion of random errors, two sets of coordinates have been obtained for the same point. raising the question, What maximum differences ΔX and ΔY may be expected at a given confidence level?

In both cases there is an accumulation of errors from three sources:

-

Influence ec of relative positional errors of the control points,

-

Influence eo of errors of the original survey (Survey I), and

-

Influence er of errors of the relocation survey (Survey II).

FIGURE 4.1 Cadastral relocation.

The total positioning error of P, which in the first case is expressed by the maximum expected distance P1 − P2 and in the second case as the maximum expected differences ΔX = X2−X1 and ΔY = Y2−Y2, is a function of the three random error sources ec, eo, and er, If Survey I and Survey II are tied to the same control points, then the influence of ec. is 0. In Case 1, the maximum expected distance P1−P2 may be expressed as the semimajor axis of a relative error ellipse between P1 and P2, Since the distance is treated as univariate, the semimajor axis of a standard error ellipse will correspond to a 68 percent (1σ) probability that the distance will not be larger than the value of the semimajor axis. To obtain a higher probability level (e.g., 95 percent) the semimajor axis is lengthened (statistically speaking). In Case 2, the expected maximum differences ΔX and ΔY can also be expressed in a statistical fashion at a desired confidence level. In both cases one has to determine the variance-covariance matrix ![]() for point P, which is treated as two separate points P1 and P2. The matrix

for point P, which is treated as two separate points P1 and P2. The matrix ![]() , is included in the general variance-covariance matrix

, is included in the general variance-covariance matrix ![]() , which contains the quality information for all coordinates involved in the survey.

, which contains the quality information for all coordinates involved in the survey.

To be able to estimate the achievable accuracy in relocation surveys the following information must be available for each individual case:

-

Variance-covariance matrix of the control points,

-

Type and standard deviations of observations in the original relocating surveys, and

-

Configuration of the survey network that connects point P with the control points.

Little work has been done to date on formulating accuracy specifications using the approach described above. A committee of lawyers and surveyors addressing the problems of cadastral standards noted that, while the function of a modem cadastral system should be to respond to the needs of the community, the actual control over the type and quality of the product prepared has largely been a function of instrumentation capabilities and historically accepted professional practices (North American Institute for Modernization of Land Data Systems, 1975). The committee concluded that

Cadastral survey standards have for the most part been based upon the capabilities of existing technology, and have been modified in response to technological change. Furthermore, the type of standard emphasized has invariably been that which conformed with existing practices. The reliance of relative precision criteria, for example, probably reflects more on the preferences of the land surveyor than on any articulated consumer requirement. The promotion of technology with ever increasing standards may not be warranted unless acceptable marginal utility can be shown. At present we do not have a sufficient understanding of consumer requirements and preferences, and we do not know how these preferences change over a period of time as the use and importance of the land changes. (Chatterton and McLaughlin. 1975)

In a study carried out for the Maritime Provinces of Canada in 1977. it was

argued that cadastral accuracy standards should be in the order of ±0.1 ft maximum error in urban areas, ±0.3 ft in suburban areas, and ±1 to ±2 ft in rural areas (McLaughlin, 1977). Much more research is required, however, before definitive accuracy standards can be put forth.

4.3

STANDARDS FOR ASSIGNING PARCEL IDENTIFIERS

The parcel identifier may be defined as a code for recognizing, selecting, identifying, and arranging information to facilitate organized storage and retrieval of parcel records. It may be used for spatial referencing of information and as shorthand for referring to a particular parcel in lieu of a full legal description.

Three important forms of parcel identifiers may be distinguished: name-related identifiers; abstract, alphanumeric identifiers; and location identifiers. Cadastral information may be retrieved through one or more of these indices. In a name code, parcel records are associated with individuals and legal entities claiming an interest to a parcel of land. An important example in current use is the alphabetical grantorgrantee index. The alphanumeric code. on the other hand. is often a random number associated with the parcel. Perhaps the simplest example is a tract index based on a sequential numbering system. Finally, a location identifier may also serve as a record index, Examples include identifiers relatcd to the Public Land Survey System and to geographical coordinates.

Location identifiers in turn may be subdivided into at least three broad categories: hierarchial identifiers, coordinate identifiers, and hybrid identifiers. The hierarchial identifier is based on a graded series of political units, as, for example, federal, state, county, town, and ward. Within the smallest territorial unit, random parcel codes may be assigned. The coordinate identifier relates a parcel to a reference ellipsoid either through the use of geodetically derived latitude and longitude or through the use of plane coordinates. Any point within the parcel, or any conventionally defined boundary point, may be chosen for the assignment of the coordinate identifier. The location index may also employ some combination of hierarchical and coordinate coding to form a hybrid index.

4.3.1

Criteria for Designing a System of Identifiers

Parcel identifiers must be considered in the design of the multipurpose cadastre both from the standpoint of initial selection and subsequent control. There is general consensus that the record code should exhibit at least the following attributes: uniqueness, simplicity, flexibility, permanence, economy, and accessibility. The requirement of a unique index for each parcel of land is the most basic criterion and is a necessary prerequisite to the development of any multipurpose cadastre. Simplicity suggests that the identifier should be easily understandable and usable to the general

public (or at least to that segment of the public that may have cause to use the system).

The identifier should be reasonably flexible. capable of serving a variety of different uses. The criterion of reasonable permanence suggests that the indexing system should not generally be subject to change and disruption. Economy relates both to the initial implementation costs and to the ongoing operational costs of the cadastral system. Accessibility refers to the ease with which the index code itself can be obtained. If a coordinate or hybrid location identifier is used as the record index, special attention must be given to the quality of the reference datum and to the accuracy of point determination.

Given the advantages and disadvantages of each indexing system, the specific choice of an optimal approach has proven difficult. The goal of the Atlanta Conference on Compatable Land Identifiers—The Problems, Prospects, and Payoffs (CLIPPP), for example, was to “recommend a single, compatible land parcel and point identifier system that would facilitate the collection, storage. manipulation, and retrieval of all land-related data” (Moyer and Fisher, 1973). This conference favored as the parcel and point identifier for universal use a number consisting of the state code number, the county code number, and the State Plane Coordinates for the point or the visual center of the parcel (Cook, 1982). Such an approach is employed. for example. in the North Carolina Land Records Management Program (North Carolina Dept. of Administration. 1981).

While the advantages of a coordinate-based identifier are well documented in the CLIPPP proceedings (Moyer and Fisher. 1973). experience suggests that the choice of a parcel index for the multipurpose cadastre in its initial stages will be dictated by local needs and resources (particularly the need for maximum accessibility and for effective administration). Nevertheless, recent developments in the software of data-base-management systems and the increasing use of multiple indices through cross-index tables permit the use of a family of parcel identifiers. The most important criteria for the primary parcel identifier at this stage are uniqueness, simplicity, and economy of maintenance. However, in the broader view, for the efficient aggregation of information related to parcels that exist in one or more cadastral systems, a uniform parcel identifier, or a set of compatible identifiers, will have to be adopted for all parcel-related data files.

What is especially important is that one of the parcel identifiers be institutionally recognized and legally defined. To ensure and facilitate its use, one parcel identifier in the land-parcel register should become the official, legal reference to all title documents affecting that parcel, that is, the general index number used by the recorder of deeds, at least for all documents filed on or after the date the register becomes available. Use of this parcel identifier would be sufficient for legal descriptions of parcels, as proposed in the Uniform Simplification of Land Transfers Act (National Conference of Commissioners on Uniform State Laws. 1977).

In addition to the legally defined cadastral parcel identifier, provision should be

made to accommodate secondary indexes based, for example, on street addresses, names, or geographic codes through the use of cross-referenced indexes.

4.3.2

Control of New Parcel Numbers

While the choice of a parcel-identifier system is of fundamental concern, attention must be directed to the allocation and subsequent control of these identifiers. Any parcel-identifier system can only work if one agency has the sole authority for assigning identifiers. This preferably should be that agency responsible for land registration.

During the course of implementing the multipurpose cadastre. the parcel identifier should be introduced during the first phase of the cadastral-mapping program. Assignment of a parcel identifier should be provisional until the cadastral maps are formally approved and registered.

The control of the subsequent allocation, re-allocation, and withdrawal of parcel identifiers is but part of the larger process of managing land-tenure changes. If the configuration of a parcel is changed (e.g., typically by subdivision), that parcel ceases to exist, and new identifiers are assigned to the new parcels. However, the original parcel remains as a historic entity. and the descriptions of it that were entered in the various registers and files when it did exist remain coded to it. Indexes that identify such “retired” parcels must be included in the records system unless provided otherwise by statute.

A special problem with the parcel-identifier system concerns the possibility of error in data processing. There are various techniques available for monitoring the fidelity of a parcel identifier from the time of its initial assignment through subsequent processing, most of which employ the addition of a redundant check digit. The simplest approach is the addition of a check digit at the end of an identifier, which is mathematically related to the sequence of digits in the identifier.