5

Organizing Other Land-Parcel Records

Cadastral record systems or files. as previously defined, are parcel oriented. Each cadastral record contains, in addition to other information about the parcel in question, a parcel identifier that is unique to that parcel. The identifier provides an ideal link to interrclate the many other files that contain information about the same parcel. The benefits of having a single agency responsible as the source for each element of land data in the public records are manifold. A cadastre that serves as this multipurpose link in a land-data system must meet a variety of requirements of other users beyond those described in Chapters 2, 3, and 4.

Currently, the most extensively developed cadastral record systems in North America are the essentially single-purpose systems of local land-title recording offices and of assessors. Widespread initiatives to modernize these systems, usually by computerizing them, have led to numerous examples of their being used for more than one purpose. The adaptation of these single-purpose cadastral record systems to other purposes also has spurred interest in systems that were designed from the outset to serve multiple purposes. Conditions seem favorable for such initiatives to succeed: adequate computing power is within the technical and financial grasp of the smallest and poorest local guvernment, the pool of talent to design and install systems is growing, officials in other governmental functions—notably planning and public works—are becoming increasingly aware of the potentialities, and the pressures to increase the cost-effectiveness of local government are growing.

The objective of this chapter, therefore. is to provide information on standards and practices that will facilitate (I) the joint development, multiple use, or both of cadastral records by local governments and other local users of land information and (2) the establishment of other registers of land-parcel data compatible with the cadastre

that can serve the broader needs of regional, state, and national government agencies, public utilities, and others.

Land-record systems can require the gathering and processing of vast amounts of information from numerous sources. This information is used to locate and identify parcels, describe them and the buildings erected upon them, and meet the specific needs of the users of the records.

5.1

MEASURING USER REQUIREMENTS

A multipurpose cadastre, as its name implies, is designed to serve more than one purpose. This means that the informational requirements of more than one set of users need to be taken into consideration in the design of the cadastre. It follows that these needs should be borne in mind in the design of any cadastral record system, even though it may be designed to serve only a single purpose.

5.1.1

Nature of Interests in Cadastral Information

While attention to user requirements is an obvious aspect of system design (see Section 5.4), the analysis of user requirements may present some special problems in the design of a multipurpose cadastre. The essential task is to determine the degree of commonality of interest in a particular data element on the part of the potential users of the information in a cadastre. Those data elements for which there is widespread interest might be maintained in an integrated cadastral record system, while those of limited interest might be maintained in a specialized system.

The study of the commonality of interest in data elements is complicated by the fact that potential users of the information in the cadastre may not be readily identifiable. Attempts to identify potential users must take into account differences in the organizational structure of local government (i.e., the existence of different types of general governments—such as counties, municipalities, and townships—and special governments—such as school districts and fire-protection districts); the functions assigned to each unit of government; and the organization and nomenclature of offices, departments, and other organizational units. Listed below are some local government offices (variously named) that are potential users of cadastral information:

Administration

Assessment

Building inspection (code administration)

Clerk

Court administration

Deed recordation

Engineering

Finance (treasurer, tax collector)

Fire and emergency medical services

Forestry

Health (disease control)

Housing code enforcement

Natural resources

Parks and recreation

Planning

Police

Pollution control (air, water, hazardous wastes)

School planning and districting

Streets and highways (traffic control)

Surveying

Transportation

Utilities (electric, gas, street lighting)

Voter registration

Water and sewers

Zoning

Other lists are found in Guidelines for Systems Analysis of User Requirements (American Public Works Association Research Foundation, 1981a) and in Monitoring Foreign Ownership of U.S. Real Estate: A Report to Congress (U.S. Department of Agriculture, 1979).

The actual information needs of these users may be difficult to ascertain. Many users, such as planners, are accustomed to having to make use of suboptimal land information. In other instances, a single characteristic customarily may be viewed in different ways. It appears that these issues have not been rigorously investigated.

Listed below are some of the areas in which user requirements may differ. Designers of cadastral record systems should explore each of these areas with each potential user of a multipurpose cadastre.

Spatial Interests. Although all users of a multipurpose cadastre may be assumed to have an interest in parcel-oriented information, they may have other, sometimes more important interests. For example, they also may be interested in areas within parcels, areas larger than parcels, or areas that overlap parts of parcels. Frequently, the interest is with buildings, which may be smaller than, larger than, or overlap the boundaries of a parcel. Larger areas of interest may be political, economic, or ecological in nature. Sometimes the interest is in relating parcels to arbitrary grid cells.

Temporal Interests. The configuration of parcels, their owners, and their characteristics ordinarily changes with the passage of time. Some users may be interested in the current situation. Others may be interested in the situation at specified intervals. Still others may be interested in the history of the changes or in summaries of changes over specified intervals such as calendar years or fiscal years.

Coverage. Requirements with respect to the coverage of parcels also may vary. Many users require information on all parcels in an area. Some users, however, may only be interested in certain parcels. Sometimes those parcels are determined by the course of events. Other times, the parcels of interest may be selected by a sampling procedure, although such an interest implies a need for some minimal amount of information on all parcels.

Subjects, The subjects (things of interest about parcels) will vary greatly among users. The interest may be with the physical characteristics of the parcels themselves, the physical characteristics of buildings and other improvements to the parcels, uses

of parcels, events (such as fires, crimes, or illnesses), transactions (such as sales or leases), the parties to such transactions, or some combination of subjects.

Precision. Users may have differing requirements concerning measurements and descriptors. Generally, obtaining greater precision requires greater expenditures for data collection and maintenance.

Linkages. Although the linchpin of a multipurpose cadastre composed of a number of separate cadastral record systems is the parcel identifier, some users are primarily interested in other, nonunique identifiers, such as street address, name (of a person or an establishment), or geographic location (relative to either a specific geographic feature or a reference framework).

Accessibility. Just as informational requirements vary, so do accessibility requirements. Some users may require immediate access to a record, document, or image. Others may be satisfied with access within a few minutes, while still others may be satisfied with overnight or even weekly access service. Among the factors that affect accessibility requirements are the volume of information that is being processed and the value of the time of the users.

5.1.2

Requirements for Land-Title Recording

Maintaining land-title records is a function of county government in the United States except in three New England states (Connecticut, Rhode Island, and Vermont), in which it is a function of city and town governments (Almy, 1979a). Hence, there are about 3000 county land-title record systems and about 500 city and town systems.

Typical and innovative land-title recording and registration practices are described in some detail in American Land Title Recordation Practices: State of the Art and Prospects for Improvement (U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, 1980). That report describes innovations in 13 localities, and a subsequent report, Profiles of the Land Title Demonstration Projects (U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, 1981a, 198lb), describes HUD-funded efforts to improve landtitle recordation and registration procedures in nine localities.

A typical land-title recording system is a register of evidence of title to real property, such evidence being contained in copies of deeds, land contracts, wills, and other documents. Title records, therefore, essentially are parcel oriented, and all legally recognized parcels are included in the system. A land-title record system is an archive that makes it possible to track changes in the configuration of parcels and to construct a “chain of title.” Such activities often are made difficult in conventional, manual systems because of the cumbersome way in which documents are indexed, and access to documents can be streamlined in a number of ways that are discussed in Section 5.3 and Chapter 6.

In a conventional, manual system, access to individual documents usually is obtained by (1) searching alphabetical indexes of the names of buyers (grantees) and sellers (grantors) or by searching a tract index, which essentially is a subdivision

index; (2) noting the location of the documents of interest in the register; and (3) reading them or obtaining copies. The location of a particular document in a register often is indicated by a numerical identifier that refers to the appropriate volume and page of the register. Other times, the reference is to a serial document number. Organizing documents in the sequence in which they are received is administratively efficient. Users of land-title records, however, often only possess information on the name of a person, the address of a property, its legal description, or an assessor’s parcel identifier. Thus, use of land-title records is facilitated if there are name, address, parcel-identifier, and legal description indexes available to locate the documents. Such indexes make it possible to link land-title records to other cadastral records.

A number of technologies can facilitate access to land-title records. Micrographics and video technologies can be used to store copies of title documents, and photocopy equipment can be used to produce copies of documents on demand. Indexes can be computerized. However, it may not be economically feasible to computerize current land-title records in their entirety, let alone historic documents, since record conversion would be a monumental task. Computer storage of title documents does become feasible when the documents are standardized.

Recording officers may be responsible for maintaining property-ownership maps, assigning parcel identifiers, and transmitting information on changes in ownership and sales prices to assessors and others.

5.1.3

Requirements for Real-Property Assessment

In the United States, local governments are primarily responsible for real-property assessment except in Maryland and Montana, where the states are fully responsible for assessment (Almy, 1979a). There are approximately 13,400 county,municipality, and township assessment jurisdictions.

Although specific responsibilities are set forth in state law, assessors generally are responsible for (1) locating and describing properties, (2) estimating their values, (3) linking them to their current owners, and (4) designating their official value for tax purposes, taking into account legal reasons for assessing them in amounts that differ from their appraised values. Accordingly, assessors must collect, store, retrieve, and analyze a great deal of information that is parcel oriented (see Table 5.1), and all parcels should be included in a real-property assessment system. Data requirements are described in more detail in Improving Real Property Assessment; A Reference Manual (International Association of Assessing Officers, 1978), which is the source of much of the material in this chapter, and a list of recommended data elements for a fiscal cadastre (assessment and taxation) can be found in Multiple-Purpose Land Data Systems, Monitoring Foreign Ownership of U.S. Real Estate (Moyer, 1979). While it is administratively convenient to revise property records as changes occur, assessors officially are concerned with the status and value of parcels on the legally designated annual appraisal or assessment date. Thus, assessors have only a limited interest in information that is of a historical nature.

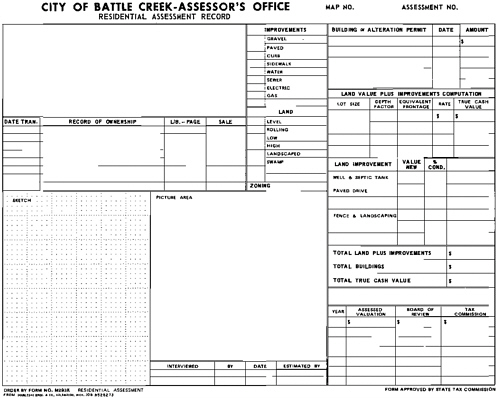

Table 5.1 Contents of Assessment Record Systems

|

|

File |

|

|

|

|

Data Element |

Legal Description (Maps) |

Property Characteristics (Property Records) |

Market Data (Sales, etc.) |

Property Ownership (Assessment Roll) |

|

Boundaries of individual parcels |

X |

|

|

|

|

Parcel dimensions and/or areas |

X |

X |

X |

|

|

Bearings (where applicable) |

X |

|

|

|

|

Subdivision names. boundaries. lot numbers. etc. |

X |

X |

X |

|

|

Governmental boundaries |

X |

|

|

|

|

Easement and right-of-way boundaries |

X |

|

|

|

|

Location and name of streets. etc. |

X |

|

|

|

|

Assessors’ parcel identifiers |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

Street address |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

Property-use classification code |

|

X |

X |

X |

|

Assessment-status code |

|

X |

X |

X |

|

Tax-rate-area code |

|

X |

X |

X |

|

Neighborhood or market-area code |

|

X |

X |

|

|

Site characteristics |

|

X |

X |

|

|

Improvement characteristics |

|

X |

X |

|

|

Building perimeter sketch |

|

X |

|

|

|

Building-cost data |

|

X |

|

|

|

Income and expense data |

|

X |

X |

|

|

Building permit history |

|

X |

|

|

|

Sale history |

|

X |

|

|

|

Sale date |

|

X |

X |

|

|

Sale price (nominal) |

|

X |

X |

|

|

Cash-equivalent sale price |

|

|

X |

|

|

Time-adjusted sale price |

|

|

X |

|

|

Sale acceptancc/rejection code |

|

|

X |

|

|

Source of sale confirmation |

|

|

X |

|

|

Type of instrument |

|

|

X |

|

|

Instrument number |

|

|

X |

|

|

Assessment/sale price ratio |

|

|

X |

|

|

Appraised and assessed values |

|

X |

X |

X |

|

Record of on-site inspections |

|

X |

|

|

|

Appeals history |

|

X |

|

|

|

Appraiser’s name (coded) |

|

X |

|

|

|

Year appraised |

|

X |

X |

|

|

Name of owner |

|

|

|

X |

|

Address of owner |

|

|

|

X |

Depending on the nature of the information and the degree to which assessment records have been computerizcd. those records may be maintained in a number of separate files.

Legal Description Files (Maps). The assessor’s primary working “file” containing legal descriptions is a set of property-ownership maps, in which legal descriptions are represented graphically, not merely in writing (see Chapter 4). Only by representing the size and shape of parcels graphically can the assessor be sure that all taxable property is assessed and that none is assessed twice. Knowledge of the size, shape. and location of parcels is essential to land appraisal. Maps also are indispensable in other aspects of appraisal operations and can serve many other purposes as well. For these reasons, it is often stated that the first requirement of a good assessment system is a complete set of up-to-date property-ownership maps.

Legal descriptions are generally printed in abbreviated form on assessment rolls, and they often are found on individual property records. Maintenance of complete legal descriptions in an assessor’s computerized records usually is regarded as a wasteful use of computer storage.

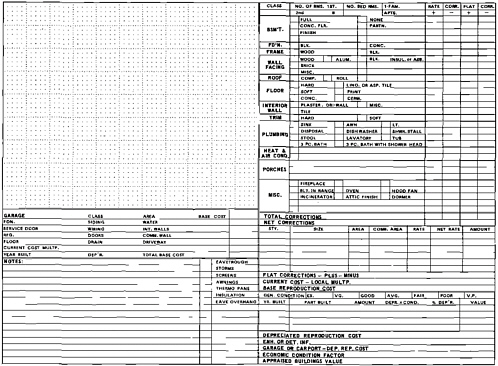

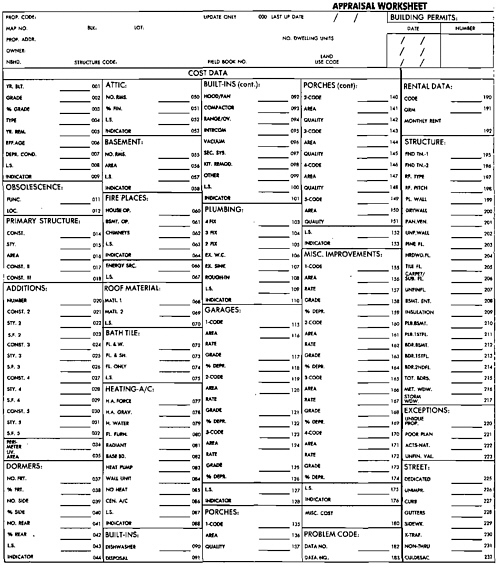

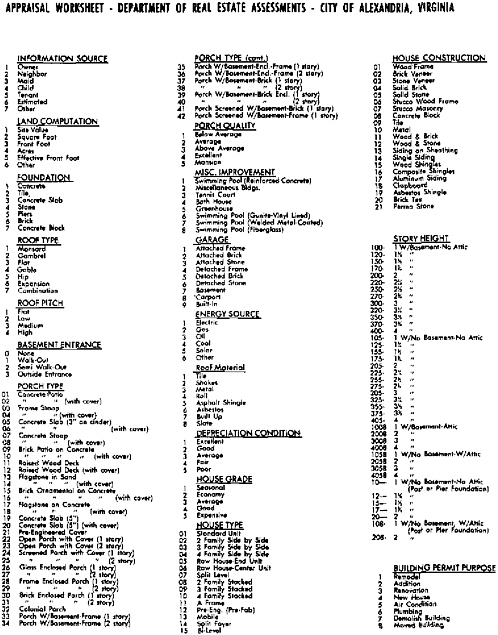

Property-Record Files. The largest file in a good real-property assessment system is the property-record file. This file contains information describing each parcel and any buildings or other improvements on each parcel. It also documents the factors and methods used in appraising each property. The specific items of information contained in a property-record file are determined by the information required to identify and describe each property, to make appraisal calculations, and to satisfy the owner(s) of the property that the assessor is familiar with it. Property-record contents also are heavily influenced by the type of property in question, the specific appraisal method or methods that the assessor uses, whether the file is computerized, and regional factors such as climate and culture. Some typical site and improvement characteristics, not listed in Table 5.1, are listed in Table 5.2 (other characteristics are identified in International Association of Assessing Officers, 1978. and Moyer, 1979). The file essentially is a record of the current status of properties, although it is not uncommon for assessors property records to contain a 5- to 10-year history of assessments, sales, building permits, and appeals.

Assessors’ property records are examined and revised virtually on a daily basis. Property-record information is used or processed whenever a property is scheduled for a visual inspection, a property is reappraised, a property is sold, a building permit is issued for the property, a property is damaged by fire or other disaster, a property owner or other person wishes to examine the record, or a property’s assessment is appealed or is reviewed by a review agency. The volume and frequency of inquiries and revisions have led many assessors to place their property records in on-line computer files. The more typical paper files of property records usually are arranged in parcel-identifier order. but they may be arranged by address, subdivision, or owner’s name.

TABLE 5.2 Site and Improvement Characteristics

|

Site/Location Topography Soil characteristics Usable land area Building setback requirements Landscaping Cul-de-sac location Corner location View Street and alley access Railroad and waterway access Available utilities Distance to shopping, etc. Nearby nuisances Zoning |

|

Building Size Ground-floor area Total floor area Leasable area Volume Building height Ceiling height Clear span Number of stories Number of units (apartments, etc.) |

|

Shape Floor area/perimeter ratio Number of corners |

|

Construction Materials Foundation Framing Floors Walls (exterior and interior) Ceilings Roots |

|

Construction Quality Quality of materials Workmanship Architecture |

|

Design Intended use Architectural style Shape of building Roof type Story height |

|

Other Building Features Number of rooms by type Heating. ventilation, air conditioning Plumbing facilities Fireplaces and similar amenities Additions and remodeling Porches and patios Swimming pools Shelter for automobiles Elevators Power equipment |

|

Age/Extent of Depreciation Chronological age “Effective” age Remaining economic life “Percent good” Condition Extent of remodeling |

Market-Data Files. Assessors often maintain specialized market-data files. These files contain data on sales prices and terms, rental revenues and operating expenses, and building costs and data on property characteristics as of the date of sale, the dates to which the rental and operating expense data applied, or the date construction was completed. While property-record files may contain identical kinds of information, the distinction between the two types of files is important. Property-record

files contain status information on all properties. while the special market-data files contain descriptions of only those properties for which the market data are available and of characteristics and conditions in existence at the time of sale, rental, or construction. Sales data and other market-data files are crucial to the development of the valuation models used to appraise all properties. Sales files may be computerized, or they may be organized similar to manual property records. Income and expense files and cost files are usually more informal since fewer properties are involved.

Property-Ownership Files. The assessment roll normally is the assessor’s primary ownership file. Nowadays. assessment rolls usually are computerized. and assessment-roll information may be available only on computer screens or on microfilm. Assessment-roll entries normally are arranged in parcel-identifier order and contain the name and address of the current owner or taxpayer; the legal description of the parcel (often in abbreviated form); the assessed value (often separate land and improvement values are listed); and such additional information as a property-use code. a tax-rate area code. tax extensions, and the amount of exemptions applying to the property. Owner’s or taxpayer’s name, address. and subdivision indexes are often prepared. Exemption applications are contained in ancillary files.

The investment required to collect assessment data (particularly property characteristics data) and to convert them into usable form is substantial. If the data are maintained, if the data base is sufficient to accommodate new and changing needs, and if the data are accessible, this investment can be shared by a number of offices and amortized over a long period of time.

5.1.4

Requirements for Land-Use Planning and Regulation

Land-use planning and regulation are essentially local government functions. Because of the diversity of planning issues and land-use control techniques, the functions are not easily defined, but they generally deal with identifying and applying ways of guiding development and use of the physical environment that promote the health, safety. welfare, and convenience of the citizenry. Planning, therefore, deals with monitoring changes in land use and in the physical environment, identifying problems, proposing solutions, and attempting to implement the most feasible solution to the problem in question.

Land-use planners require population, economic, social. and environmental data. Planners are increasingly likely to have data systems that are designed to meet their particular needs, examples of which are described in Computers in Local Government: Urban and Regional Planning (Auerbach Publishers. 1980a) and in the October 1981 issue of Planning, which is published by the American Planning Association, Chicago, lllinois.

Cadastral records can be used in a number of planning activities, such as making land-use inventories; monitoring development; evaluating proposed developments;

Table 5.3 Examples of Cadastral Data Elements Used in Planning

|

Site/Location Characteristics Street address Geographic location Political subdivision codes Parcel dimensions and/or areas Easement data Street and alley access Railroad and waterway access Available utilities Distance to shopping. etc. Topography Soil and subsoil characteristics Groundwater and surface-water characteristics Natural vegatation Presence of air and water pollutioncausing agents |

|

Land-Use Data Land-use code(s) Business license history Number of residents Number of employees On-site parking spaces Zoning |

|

Improvement Characteristics Story height Floor-area ratio Dwelling units Other units Condition of buildings Building permit history Landscaping |

selecting sites for public and quasi-public facilities (such as schools, fire stations, hospitals, and power plants); making transportation plans; and delineating zoning, redevelopment, rehabilitation, historic, and other districts. The administration of zoning and subdivision ordinances is parcel-specific. Urban-design activities often are parcel oriented. Cadastral data elements that are used in planning include those listed in Table 5.3.

5.1.5

Requirements for Public Works

Public works administration involves activities that relate to the design, construction, maintenance, and operation of public buildings, utilities, transportation systems (including streets and roads). and other facilities. Public works officials may be responsible for the analysis of the need for such capital improvements, and they may be responsible for selecting and acquiring sites. In these respects, their needs of cadastral data are the same as planners. Once sites have been acquired and the infrastructure has been constructed, there is a need for information on the physical characteristics and precise location of the infrastructure relative to rights of way, other utility systems, and abutting parcels, as well as for information on changing service demands. A particular concern has been mapping and maintaining records on underground water, sewage, electricity, gas, telephone, and other systems. The best source of information on these subjects is the Computer Assisted Mapping and Records Activity System Manual published by the American Public Works Association, Chicago. Illinois (1980–1981).

5.1.6

Requirements for Public Health and Safety Functions

Several governmental functions involved in protecting the health and safety of the populace originate or use parcel-oriented data. Building-code administrators are responsible for ensuring that buildings meet safety standards. In fulfilling this responsibility, building-code administrators review demolition, excavation, construction, and alteration plans and issue permits if the plans conform to the code. In the process, they collect copies of architectural drawings and specifications that contain information on the size of structures, construction materials, and construction methods. This information can be useful to assessing officers, police officers, and fire fighters. Assessors also use building-permit information to alert them to possible changes in property characteristics. Information on the number and value of building permits is used in some economic studies. Building inspectors must maintain systems for keeping records of the status of each permit that has been issued as well as of certificates of occupancy, which are issued when new construction or remodeling meets safety standards, and of records of violations of the code. Information on violations is useful in a variety of other governmental functions. Permits and similar documents are usually filed in permit number order. although cross-references to legal descriptions and addresses are useful in locating buildings in the field.

Cadastral records also are used by police, fire, and health departments. Such records are used in identifying potential hazards, in selecting sites for fire and police stations, and in the monitoring of septic and sewer systems.

5.1.7

Requirements for Financial Management

Cadastral records are used in at least two aspects of financial management: realproperty taxation and fiscal-impact analyses. The real-property taxation function takes up where the assessment function leaves off (and some finance departments are responsible for the assessment function, while some assessors are responsible for property-tax collection). The taxation function includes (1) the issuance of propertytax bills, (2) receiving tax payments and maintaining records for those payments and amounts due, (3) maintaining a record of tax liens, and (4) instituting enforcement procedures when taxes become delinquent. Real-property taxation systems may be integrated in one way or another with real-property assessment systems and with governmental financial-management systems.

Fiscal-impact studies often are both a financial-management concern and a planning concern. Hence, they may be performed by either finance or planning departments. When the studies involve specific development proposals or changes in the property-tax base, property-tax rates, or property-tax policies, cadastral data are required in the analyses. Perhaps, the best reference on fiscal impact studies is The Fiscal Impact Handbook: Estimating Local Costs and R Revenues in Land Development (Burchell and Listokin, 1978).

5.2

STANDARDIZING THE DESCRIPTIONS AND CODING OF PROPERTY CHARACTERISTICS

The sharing of land-parcel data among the users of a multipurpose cadastre will depend on their use of common procedures for describing and coding property characteristics. Describing a property characteristic involves a depiction in words or a representation by a picture. One may draw sketches, take photographs, take measurements, make counts, compile lists, sort into classes, or assign ratings. The choice as to which techniques to employ depends on such factors as the nature of the characteristics being described and the purposes for which the data are being collected. Coding is the reduction or abbreviation of a description to a more manageable size through the use of letters, numbers, symbols. and fewer words. For universal use of the data, these codes must be standardized.

5.2.1

Alternatives for Classifying Land Parcels

Descriptions of land-parcel characteristics may be objective or subjective. Subjective descriptions require more intellectual effort, whereas objective descriptions are made more mechanically. Similarly, a description may be qualitative or quantitative. A house may be described as a mansion because mansions are “large” and the house in question is the largest house around—a qualitative description. Or the house may have been classified as a mansion because an assessor’s cost manual specifications indicate that, among other things, mansions must have a ground-floor area equal to or greater than 3000 square feet, and the house in question has a ground-floor area of 3130 square feet—a quantitative description. There is often a close correspondence between subjective and qualitative descriptions and between objective and quantitative descriptions.

Property characteristics may be continuous, discrete, or dichotomous. A continuous characteristic or variable is one that may take on any numerical value. Building area, for example, is a continuous variable. A discrete variable, such as number of fireplaces, can take on any whole number value, usually within certain limits. The number of rooms in a dwelling ordinarily would be thought of as a discrete variable, although “half-room” counts are sometimes used. Dichotomous characteristics or variables are those having to do with the presence or absence of a condition. They are usually described by answering a yes or no question. The variables arising from the answers to such questions are often called “dummy” variables. Examples of questions that create dummy variables are, “Does this site have lake frontage?” and “Is this property defined by the Public Land Survey System?”

Some characteristics, such as construction quality and building condition, can be treated as discrete variables by developing a rating scheme or as series of dummy variables, Building condition or state of repair, for example, could be described on a scale, of, say, 1 to 10 or as poor, fair, average, or good.

Rating schemes can be based on an absolute standard. that is, a standard that applies to all properties in the system, or they can be based on a relative standard, that is, one that changes from neighborhood to neighborhood or from one group of properties to another. If the rating standard is absolute, a building described as being in good condition in one location would also be good in any location. An example of a variable described by a relative standard is a typical or representative lot, the determination of which is based on the average size of lots in the neighborhood or area.

Coding schemes should account for all possibilities (be exhaustive). and coding categories should be mutually exclusive. In addition, property characteristics should be described and coded in a consistent way. Interestingly, when multiple regression analysis is employed in property valuation, consistency can be as important as accuracy, since the mathematical logic of the technique can compensate for inaccurate descriptions as long as they are consistently inaccurate. Obviously, consistently inaccurate data would be useless for most other purposes.

Quantitative and objective methods of describing land-parcel characteristics result in more consistent descriptions. They require explicit consideration of more details and therefore are apt to be more time-consuming, although less experienced data collectors (e.g., temporary data collectors and trainee appraisers) can be used. Consistency in the coding of qualitative or subjective characteristics, on the other hand, requires well-trained and experienced data collectors (e.g., appraisers and data-collection specialists).

5.2.2

Characteristics of the Land and Location

It would be difficult to construct a list of all characteristics of land parcels that might be indexed with reference to the multipurpose cadastre. The following are characteristics that are important to many users and for which guidelines for describing and coding may help to make the various registers of land data more compatible. Many other data elements are of interest to only one of the user departments and thus do not warrant discussion here.

Parcel Size. Parcel size may be described in terms of parcel dimensions (e.g., lot frontage and depth). land area, and usable land area. Parcel dimensions and area are obtained from surveys, plats, or maps. Usable land area is determined by reference to actual parcel dimensions and area. land-use controls (e.g., permitted coverage of the parcel—building setback and side- and rear-yard requirements), shape characteristics (e.g., extremely narrow parcels), soil characteristics, and terrain and topographic characteristics (e.g., location on a hillside or a ravine or in a floodplain). Usable area, therefore, is determined by a combination of objective measurements and subjective, personal observations. Parcel size also may be described in relative terms. For example, a lot may be described as “typical” or representative of surrounding parcels.

Land Use. Land use may be described in terms of whether the land is unimproved

(i.e., without buildings) or improved and, if the land is improved, what the use(s) is (are). Unimproved land may be described in terms of actual use (e.g., agricultural use), in terms of likely use (e.g., surrounding use or permitted use), or in terms of subdivision characteristics. Coding improved land is more complex. Not only should all significant land uses be included in the scheme, but mixed uses should be accommodated. Techniques for dealing with mixed uses include (1) coding only the predominant use, (2) coding the highest and best use, (3) devising a coding system that permits secondary uses to be coded, and (4) using building-use codes as well as land-use codes. The standard procedure is to draw up a list of land uses and assign code numbers to them. See, for example, Standard Land Use Coding Manual: A Standard System for Identifying and Coding Land Use Activities (Bureau of Public Roads and U.S. Urban Renewal Administration, 1965). Standard property-use coding systems have been developed by assessment agencies in 33 states (Almy, 1979b). and the International Association of Assessing Officers (1981) has published a standard on property-use codes. Usually land uses are grouped according to broad classes (e.g.. residential, commercial. industrial); within each major group more detailed land-use descriptions are found.

The Baltimore Land Use Coding (BLUC) System, which is a good example of a locally developed system based on the Standard Land Use Coding Manual, consists of a five-digit number that defines to four levels of detail the existing predominant use of a parcel of land and indicates the general secondary use. The first digit identifies the predominant use of the parcel as being in one of the following major categories: 1, residential; 2 and 3, manufacturing—two groups; 4, transportation, communication. and utilities; 5, trade; 6, services; 7, cultural, entertainment, and recreational; 8. agriculture; and 9, undeveloped land and water areas. The second digit is a refinement of the first, a subcategory of the major category. The third digit further refines the second, and the fourth digit refines the third.

As an example, code 2184 describes land used for “distilling, rectifying and blending liquors.” The first digit, 2, identifies this land as being in the major category “manufacturing.” The second digit, 1. identifies the land as being for the manufacture of “food and kindred products”; and third digit, 8. refines this as the manufacture of “beverage.” The fourth digit, 4. identifies the beverage manufacturing as “distilling, rectifying and blending liquors.” Through this four-level structure of coding, information may be retrieved to the degree of detail considered most appropriate for analysis and presentation of the data.

By addition of the fifth digit, information on parcels with a secondary use may be obtained. There are eight categories of secondary use, corresponding to the eight major categories of predominant use listed above. If, in the previous example of land being used for “distilling, rectifying and blending liquors,” a wholesale trade in the product was also carried on at this location, the number 5 would be placed in the fifth-digit position. This would indicate that trade was carried on as a secondary land use.

Detroit, Michigan, has taken a different approach: in addition to a three-digit

land-use code. Detroit also employs a three-digit building-use code. The land-use code always begins with zero to distinguish it from the building-use code, and the second digit is one of the following eight major categories: 1, residential; 2, commercial; 3, industrial; 4, utilities and communications; 5, transportation; 6, public and quasi-public; 7, outdoor recreation; and 8, extractive and agricultural. The third digit is a refinement of the second. As an example, code 032 describes land use for specially constructed industrial buildings.

The more complex the coding scheme, the more knowledge is required of data collectors.

Service and Transportation Network Access. Available services (e.g., access to streets or roads, alleys, railroads, waterways, telephone, electricity, gas, water, and sewers) affect the suitability of land for development and hence land value, and information about these services is useful in a number of ways. With the exception of underground utilities, these property characteristics can be observed easily and coded yes or no. Service to the property by underground utilities may be detected by the presence of street lights, meters, and above-ground connections or by recourse to utility maps. The location of utility lines eventually should be incorporated in the multipurpose cadastre.

Locational Characteristics. Locational characteristics that are external to the parcel, such as an outstanding view, the presence of a nuisance, or distance to shopping, can have important effects on land values. These characteristics are also useful for descriptive purposes. Nuisance and view characteristics usually must be measured subjectively. A rating scale that imparts a degree of consistency in describing these characteristics may be developed. Distance variables are difficult to measure but may be obtained by scaling from maps, by counting city blocks in urban areas, and by calculating distances using the geographic coordinate parcel identifiers of the parcel being described and of a parcel representing the target or reference point.

Neighborhood. It can be seen that often many of the site or location characteristics described above are common among adjacent parcels. In such situations, needless duplicate description and coding efforts are likely. One way to overcome this problem is to use the concept “neighborhood” as a generalized location variable. Neighborhood boundaries can be delineated, and factors to be considered in delineating neighborhood boundaries include land use; homogeneity of property characteristics; the presence of schools, churches, and similar cultural “magnets”; physical barriers; and trends in property values. In some areas, municipal boundaries and the boundaries of other tax-rate areas have also been found to be important neighborhood boundaries.

5.2.3

Characteristics of Structures

Building Size. Building size may be described in terms of ground-floor area, total floor area, volume, building height, number of stories, or a combination of several of these. Other, less-complete. measures of size include leasable area, ceiling height, clear span, and number of units such as apartments. In theory at least, areas, heights, spans, volumes, and units can be measured with great precision and are therefore objective characteristics. Generally, exterior dimensions are measured, since measuring interior dimensions usually is not cost-effective except in measuring ceiling heights and spans in industrial buildings. Taking building measurements is not necessarily easy, however. Vertical measurements are difficult to obtain. Curved walls and some angles are difficult to measure. Other horizontal measurements may be difficult because shrubbery, fences, and other obstacles impede the process.

Shape of Building. The shape of a building of a given floor area has an important bearing on the cost of a building, and shape characteristics are important in appraisals based on replacement cost. Shape may be described in terms of the ratio of floor area to perimeter and the number of corners or by matching the shape of the perimeter of a building with a generalized pattern (rectangular L-shaped, T-shaped, and H-shaped structures).

Design. Design characteristics can be described in terms of intended or designed use (e.g., single-family residence, gas station), arrangement of stories (e.g., two-story, one-story, split-level, trilevel), type of roof (e.g.. flat, mansard), period of construction (e.g., modern, conventional, old), and architectural style (e.g., colonial, Cape Cod, ranch). Intended use can be coded in the same fashion as land use. Decisions have to be made about how to treat situations in which intended use and actual use differ (a house used as a restaurant). If the characteristic is used only to inventory land uses, current use is generally best.

The classification of story height can present problems. One is the classification of finished areas under sloping roofs. Buildings with mixed story heights are also difficult to describe.

Period of construction can be coded with considerable precision as long as the ages of properties are generally known and as long as the boundaries of periods are specified.

Architectural style is difficult to describe effectively because architectural styles are imprecisely defined, and many buildings contain elements of many styles.

Construction Quality. Like neighborhood, construction quality is a composite characteristic. It describes the cumulative effects of workmanship, the costliness of materials, and the individuality of design. With respect to construction quality ratings, an important point is that most rating schemes are designed to facilitate the use of a specific set of cost schedules used in estimating the replacement costs of buildings.

Construction quality ratings are assigned on the basis of matching a building to a set of specifications. The specifications for each class or grade should identify and

describe the specific characteristics of building materials, workmanship, and other features that distinguish that class from the others. Quality-class ratings should be assigned without regard to the state of repair of the building. In other words, data collectors should assign the rating as though the building were of new construction. A knowledge of historical construction practices is helpful in assigning quality-class ratings to older buildings.

Construction Materials. The materials used in the construction of the foundations, frames, floors, walls, and roofs of buildings are required in cost estimating and in describing buildings. Many materials (e.g., wood, brick, concrete) can be observed and identified without any special training (see Section 5.3.4).

Other Building Features. Information on many other building features may be needed to describe a property adequately. The features that are important vary, of course, with property type and locality. Many of these characteristics can be described through the use of yes or no variables. Others can simply be counted.

Age/Condition. Buildings are not indestructible, and it is important to gauge the effects of aging and wear and tear on buildings. Usually both age and condition are described.

Age may be described simply in terms of chronological age or in terms of “effective age” (i.e., age adjusted for condition and remodeling). Age is sometimes described in terms of remaining economic life, which is the future period that a building is expected to contribute positively to the total value of the property. Chronological age can be determined accurately from assessment or building-inspection records but is a comparatively meaningless characteristic if condition is disregarded. Effective age and remaining economic life are, on the other hand, nebulous concepts that are difficult to estimate.

Condition, also a subjective concept, can be described in terms of a rating scale (e.g., fair, average, good) or in terms of a continuous scale (e.g., percent good).

Although standard land-use codes are available, there remains a need for a standard classification of the characteristics of structures.

We recommend that the National Association of Counties institute a project to provide the counties with a draft of a standard classification of the characteristics of structures.

Since improvements in this standard classification of the characteristics of structures will come through its use, there should be a continuing administrative unit that can update this classification and provide the necessary information to all counties

5.3

PROCEDURES FOR COLLECTION AND MAINTENANCE OF COMPATIBLE DATA

The work of data collection and maintenance represents the capital investment in an existing register of land-parcel data. To preserve the future value of this important

public asset, the collection and maintenance work must be consistent in its adherence to standard procedures, and the level of confidence in the accuracy of each sector of the data base must be known.

The importance of these procedures is underscored by the findings of a recent survey of opinions of 174 experts in computerized land-data systems. The two factors most often rated high in importance for successful implementation of a land-data system were (1) a defined responsibility for the sources and accuracy of each record and (2) standards for the quality of data that may be entered (Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, 1982).

Data-collection efforts are of two general types: initial, comprehensive data-base building efforts and data-base maintenance efforts. The former type of effort is necessary whenever new applications require additional data or whenever data-maintenance efforts have been badly neglected or are currently inadequate to keep abreast of changes in properties.

Data-base building efforts involve the following steps: (1) determining data needs (see Section 5.1), (2) developing a system for describing and coding property characteristics (see Section 5.2), (3) designing data collection forms (see Section 5.3), (4) selecting and training the data collectors, and (5) managing the data-collection efforts.

Data-base maintenance efforts are of two types: (1) efforts triggered by the issuance of building permits or similar property-specific change notices and (2) general field reviews designed to verify the correctness of current information and to detect changes that were not picked up by other means.

5.3.1

Typical Data Sources

This section identifies typical sources of cadastral data for which standard collection procedures are needed. In general, the same sources are used in both original and maintenance data-collection efforts, although differences in collection practices will be noted.

Deeds and Other Real-Property Transfer Documents. Deeds and other real-property transfer documents may provide information on (1) the identification of owners of interests in real property, (2) the nature of those interests, (3) the identification of the parcels involved (legal descriptions), (4) the type of transfer (deed, land contract, will), and (5) the prices and terms of sales or other transfers.

Building Permits. Building permits, in addition to the regulatory purposes that they serve, alert assessors and others to possible changes in the physical characteristics of buildings and other permits. The acquisition of building-permit information facilitates the timely and efficient revision of cadastral records, particularly when the contemplated building activity is described.

Planning and Zoning Documents. Planning and zoning actions (zoning changes, adoption of a master plan, urban renewal or redevelopment requirements, building-

permit freezes, or sewer moratoria) may determine whether land can be developed and how property can be used, and they also influence property values. To the extent that planning actions and land-use controls directly affect individual properties, infomation about such actions and controls should be indexed by cadastral parcel number.

Aerial Photographs, Surveys, and Plats. Aerial photographs, cadastral surveys, and plats may provide information on the location, the size and shape, the use of parcels, and the occurrence of changes in the inventory of parcels, land uses, and improvements. Such information obviously is crucial to the origination and maintenance of cadastral records.

Information Supplied Directly by Property Owners. Property owners themselves can be highly useful sources of land-parcel data. They may be called on to verify or supplement data on property characteristics, sales prices and terms, rental income and expenses, and construction-cost data. Formerly, in assessment administration, property owners were almost exclusively relied on as the source of information on the nature, extent, and value of their properties. Such exclusive reliance resulted in the property tax being a tax on honesty, and great reliance on property owners became discredited. Recently, limitations in assessment budgets have caused assessors to revaluate property owners as a source of information. Some jurisdictions now provide property owners with detailed descriptions of their properties so that they can verify or contest the accuracy of the information on which their assessments are based.

Field Canvasses. The preponderance of information required in local government functions such as planning, assessment, and code enforcement is obtained by staff or contractor personnel through on-site, visual inspections. These inspections provide information on the characteristics of land parcels and of improvements on those parcels. Some jurisdictions recently have experimented with video technologies as a means of obtaining a visual record of properties.

Other Sources. The real estate industry, particularly real estate multiple-listing services, brokers, and private fee appraisers. can be a source of cadastral data.

5.3.2

Designing Data-Collection Forms

Data-collection forms traditionally have been made of paper. Portable data-entry devices, which can be used to collect, edit, and update records, may make such forms obsolete in computerized land-record systems. Nonetheless, some of the principles of forms design remain.

Data-collection forms may serve several purposes, depending on the application in question and on the design of the record system. A major purpose is to serve as either a temporary or semipermanent repository for information collected in the field. In a fully computerized cadastral record system, the useful life of a data-collection form ends when the data have been entered in and accepted by the computer. In a

manual or partly computerized system, a form may serve as the official record itself, in which case its useful life will be indefinite, lasting as long as the property exists or until a new system is implemented. In manual or partly computerized systems, data-collection forms also serve as repositories of information about events and transactions and about administrative processes and decisions. In assessment, for example, manual data-collection forms, which are commonly known as property-record cards, also would contain information about sales, building permits, and assessment appeals and would document appraisal calculations and value conclusions (see Exhibit 5.1).

Data-collection forms also serve such purposes as facilitating the collection of property-characteristics data in the field, the conversion of such data into computer-readable form, and the making of those appraisal calculations done by hand.

Where the land-data registers are computerized, the design of a data-collection form is not likely to matter to any agency other than the one that collects and enters the data. Other users normally would want the data only in machine-readable form. However, where the shared data files are manual, the design of the forms will need to be a compromise among the needs of the several users.

In the design of forms for computerized systems, roughly equal consideration should be given to facilitating field operations and data entry; it is not necessary to provide for manual calculations or to be concerned about the format of reports, since the computer can reformat the data in any convenient way. However, consideration should be given to using cadastral record reports such as an appraiser’s worksheet as a turnaround document for updating an existing record (Exhibit 5.2). If the system is a manual one, the compromise should consider ease of collection, ease of calculation, and ease of reading.

Other format and design issues include the size of the form, the weight of paper, and whether the form should be a single sheet, an envelope, or a folder (the latter two types being considered in manual systems in which supplementary documents may be part of a record). It is generally desirable to employ several specialized property-record forms rather than one all-purpose form. For example, an assessor might want separate forms for single-family dwellings, income-producing properties, industrial properties, agricultural properties, and so on. However, the forms should all have a similar format.

Data-collection forms should be designed to encourage accurate, complete, and consistent data. These objectives can be achieved by having variable labels that are clear, including variable numbers with each variable; having coding categories that are labeled, are exhaustive, and are mutually exclusive; providing sufficient space for recording numerical data; requiring a positive response for all variables, so that a blank means that the variable was overlooked and not that the property does not have the characteristic; and maximizing the use of checks or circles to ease and speed the recording of data.

5.3.3

Designing Data-Collection Manuals

A data-collection manual is an important element in a cadastral data-collection program. The objectives of a coding manual are to expand knowledge about the property characteristics being described, to achieve accuracy and consistency in describing and coding property characteristics, and to speed the data-collection effort. These objectives are achieved by describing and explaining the content of data-collection forms, with explanations of purposes, definitions, and instructions for each data item

The purpose of an item should be given in cases where its intent is not obvious. Explanations of the purpose of collecting various items can assist data collectors to make correct decisions when confronted with unusual situations in the field.

Definitions of terms provide another crucial control on observations. They provide checks in several respects. They define the limits of the observations and are designed to elicit precise observations within the specified limit. They ensure that each data collector defines terms and evaluates items within the same frame of reference as every other data collector. They are often intentionally rigid so that there will be little opportunity for individual interpretation. A difficult aspect of the formulation of a good definition is to provide rules that, to the greatest extent possible, guarantee consistency and simultaneously allow enough flexibility to accommodate unexpected circumstances. Therefore, subrules sometimes must be built into definitions to accommodate special exceptions. Definitions should also be designed for internal and external consistency. That is, they should be considered as elements of an overall description scheme and never as isolated from or independent of one another. Finally, definitions must work for the data collectors who will use them. If the definitions are too simple, data collectors will become uncertain and confused. If the definitions are too detailed, they become intimidating, cumbersome, and unworkable. A delicate balance is necessary in designing definitions that yield good data. Often a picture or a sketch is the simplest way to define a characteristic.

Instructions are used where difficulty is anticipated in describing an item because detailed, specific observation is required. Each step entailed in describing the item should be specified in these cases. In addition, separate guidelines should be provided in cases where exceptional circumstances are anticipated.

5.3.4

Editing and Auditing Cadastral Records

Data edit and audit procedures are an integral part of an overall effort to ensure that cadastral records are complete and accurate. Data edit and audit procedures provide notice of errors in the data and warmings about possible errors or unusual situations. They can be done manually or computerized, although computerized edits generally are more thorough and cost-effective. Computer-generated edit reports can indicate whether the condition that has been detected is an error or is a warning and can briefly describe the condition. Edit routines should check the following:

Missing Data. An error message should be issued each time missing data are detected. Data-coding procedures should minimize value blanks in the data.

Valid Characters. An error message should be issued if invalid characters are detected, that is, the routine should ensure that only numerical characters are used in numerical fields and alphabetical characters in alphabetical fields.

Valid Codes. An error message should be issued each time there is an invalid code. For example, a 3 appearing in a dummy-variable field where only 0 or 1 is valid is an error. Similar checks should be made of use codes, map numbers. and the like.

Normal Ranges. A warning message should be issued each time a numerical value falls outside a prespecified normal range. For example, an assessor might specify that the normal range in total floor area of residences in a neighborhood is between 800 and 3000 square feet. A house with a total floor area outside this range would trigger a warning message. All warning messages should be checked out, and data errors should be corrected. It is desirable for edit routines to have a way of flagging valid exceptions to normal ranges. Suppose, for example, that a house in the neighborhood discussed above had a total floor area of 3200 square feet. A flag acknowledging this fact would save the effort of checking out total floor area each time the edit routine was run. Judgment must be exercised in setting normal ranges. Tight limits will result in unnecessary warning messages, whereas loose limits will result in too few messages.

Data Consistency. Error and warning messages can be issued whenever an inconsistent or illogical relationship exists between the recorded data on two or more property characteristics. For example, a count of bedrooms in excess of the total number of rooms should result in the issuance of an error message. An assessor might decide that the number of bathrooms is normally less than the number of bedrooms, and bathroom counts equal to or exceeding bedroom counts would cause a warning message to be issued. Another consistency edit might be to divide the total floor area of a building by the number of rooms and compare the resulting average area per room with a specified normal range of area per room ratios. Deviations from this normal range might indicate errors in room counts or errors in area measurements. The range of consistency edits is limited only by the ingenuity of the editor and the resources available to investigate possible errors.

Check Digits. Parcel identifiers and other numerical quantities can have a check digit assigned to them that helps prevent transpositions and other data-entry errors.

Edit routines should perform all edits on a property record before moving to the next record. Some edit routines move to the next record after the first error or warning condition has been detected, leaving the detection of other error-warning conditions to subsequent edit runs. Such routines are inefficient and demoralizing to the staff assigned to checking error and warning messages.

In some cases it is desirable to reinspect a sample of properties to ensure that

information is being coded accurately. This is an expensive quality check and should be reserved for checking the work of new, temporary data collectors and trainee appraisers and for verifying the quality of the work of contract data collectors.

At every stage of the data-collection program, data completeness and accuracy should be stressed. Errors and omissions are expensive to correct.

5.3.5

Data Maintenance

Property characteristics are always changing, and, if an effort is not made to keep the data on property characteristics up to date, the resources expended in collecting the original data are soon wasted. There are basically two approaches to maintaining property characteristics data: building-permit monitoring and periodic reinspections.

As previously mentioned, building permits are used to alert assessors and others to changes in properties. When a building permit is received by an assessor’s office and the permit is for an assessable construction activity, the property’s property record form should be pulled or flagged so that the construction activity can be monitored. After the data collector has determined that construction activity has stopped or the permit is no longer in force, the record should be returned to the property-record file or the flag removed.

No matter how good a building-permit reporting and monitoring system is, undetected changes in properties will occur continuously. Cadastral record managers should therefore periodically reinspect all properties in order to verify and update the information on hand for each property. Annual visits are optimal from an appraisal accuracy standpoint, but visits of that frequency may not be administratively feasible. Visits should at least be scheduled in conjunction with reappraisals. It is important to note that the chief function of these inspections is to verify rather than to collect information. Therefore, a drive-by inspection, during which the property and its record are visually compared, is often sufficient. Two-person teams of appraisers, in which one drives and the other handles records, can review and verify several hundred records per day. Visits may be supplemented with information obtained from taxpayer returns and from an examination of aerial photographs. Changes indicated by these sources should be verified in the field. Information supplied by taxpayers during assessment review and appeal proceedings can likewise alert assessors to inaccurate or out-of-date information on property characteristics.

5.4

SYSTEM DESIGN AND DEVELOPMENT PROCEDURES

The managerial, technical, and communication skills of system designers, users, and local government managers are challenged in the development of a land-records system based on the multipurpose cadastre. A hallmark of a successful system-development activity is careful attention to each step in the system-design, -devel-

opment, and -implementation process, which is sometimes called the system “life cycle” (Young, 1980a). As previously mentioned, defining user requirements (see Section 5.1) is one of the early steps in system design and development. Other steps in the process include planning, analysis, design, development, and implementation. These subjects are briefly reviewed below. The discussion deals generally with application-system design, since record-system design generally is an integral part of an application-system design effort. More comprehensive treatments of system-design procedures are found in American Public Works Association Research Foundation (1981a), Auerbach Publishers (1980b), Donaldson (1978), Fife (1977), and Giles (1974).

5.4.1

System Planning

Effective project planning is crucial to the successful development and use of a multipurpose cadastral record system. The plan identifies needs that the system is to meet, the steps to be taken in implementing the system, resource requirements, and timing considerations. The plan also serves as a project control tool and is used to measure progress. Necessarily, the plan should be in writing.

A major part of the planning effort is scheduling. Scheduling involves dividing the overall process into discrete tasks and subtasks, noting which tasks can be begun only after other tasks have been completed and which tasks can be performed simultaneously; estimating realistic production rates and available resource levels, particularly personnel, for each task; and depicting time and resource requirements for each task on a Gantt chart or some other form of bar chart. A refined schedule should be made during the system-development phase as soon as major features of the system are decided on. More sophisticated project planning and management techniques, such as critical-path management/program evaluation and review techniques (CPM/PERT), should be used if the project is large and well analyzed.

CPM/PERT analyses are built around network diagrams that show the sequences of tasks as well as a single estimate of each task’s time requirement and cost per unit time (CPM) or three estimates of each task’s time requirement such as optimistic, probable, or pessimistic (for PERT). These estimates are then analyzed by machine or by hand to identify those tasks that are “critical” as opposed to those tasks that can be prolonged. Total estimated time is then compared with available time. If available time is inadequate, the project may be “crashed,” which means determining which tasks can be most economically accelerated in order to meet tighter time requirements. As the project progresses, the project manager notes time (and cost) milestones achieved and crashes the remaining tasks as necessary when delays are encountered.

Sometimes a feasibility study is conducted as part of the planning process (Young, 1980b). In many respects, a feasibility study is a preliminary system design effort, the purpose of which is to determine whether the system can be justified in terms of services, costs, or both.

5.4.2

System Analysis

The functions and responsibilities of the agencies that will be using the multipurpose cadastral record system must be carefully analyzed to determine the scope of the various applications and, therefore, the capabilities required of the system. System analysis should begin to identify the resources required in system design, system implementation, and system maintenance. The analysis should identify data requirements and should coordinate data-element definition and related requirements of the various users. An estimate of the benefits and costs associated with each application will help determine priorities among the various possible applications (King and Kraemer, 1980). Consideration should be given to satisfying expectations of early payoffs by developing the system in a modular fashion, if possible.

System analysis begins with interviews with key individuals in user agencies and groups. The purpose of these interviews is to determine functional responsibilities; information needs; analytical and decision-making processes; and sources. availability, and condition of existing data. An interview guide or an interview form should be prepared to ensure that all relevant lines of inquiry are followed with each interviewer. Copies of procedural manuals, forms, and reports that are used, processed, or prepared should be carefully reviewed. A helpful intermediate step in the analysis of information flows is to create two matrices, one showing data elements and their users and the other showing data elements and their sources. The interview notes and the matrices are then used to prepare an accurate description of information processing by the entities involved.

5.4.3

System Design

The system analysis is used as the basis for system-design activities. The first step in designing the system is to develop a rough concept of what the system is to be. Brainstorming sessions involving key users and technical personnel can be helpful in the conceptualization process. After decisions on the general system features are made, the design effort turns to more detailed concerns.

The system itself should be decomposed into tasks. A narrative description of each task should be prepared. The narrative would indicate whether a particular task or subtask was to be performed by human or by computer. For each computer task, a program solution should be prepared to guide the programmers. A data dictionary also should be prepared.

There are several useful new programming techniques that are oriented toward the human side of computer use. The techniques have different labels applied to them—for example, “human engineering,” “functional design,” and “improved programming technologies.” Components of the techniques, also identified by buzz words, include top-down program development, hierarchy plus input-processing output (HIPO) as a design and documentation aid, structured programming, chief programmer teams, development support libraries, and structured walkthroughs.

These techniques offer a number of benefits. The data base is defined early, before programs are written to retrieve information. This helps to avoid problems that sometimes arise when different parts of a program are written by different programmers at different times—parts that later have to be meshed together. System and program documentation is written as the system design and program structure are developed. Documentation is, therefore, more complete, accurate, and useful. The documentation also is organized in hierarchical levels, usually by function, making it easier to locate specific components of the program structure. Program code is easily intelligible to other programmers, and programs are easier to modify. The techniques also necessitate regular communications among users, system-development personnel, and data-processing operations personnel. Taken together, these features of the improved programming techniques can increase the confidence of both programmers and users in the programs and, therefore, in the system.

5.4.4

System Development and Implementation

System-development activities take place concurrently with system-design activities. An early decision is whether the system is to be developed internally or acquired from some external source (see Section 5.5). No general recommendation can be made as to which alternative is preferable. On the one hand, complete reliance on internal development may result in system-design personnel redeveloping existing systems while ensuring that the system meets the specific needs of the locale in question. On the other hand, systems developed elsewhere are seldom, if ever, completely transferable and, if they were, probably would not meet all the requirements of the host users. In fact, there appears to be an inherent contradiction in designing systems that are at once integrated and transferable. Of course, system transfers can occur at several levels, ranging from system concepts down to specific program code, and system components usually can be transferred more easily than entire systems.

A related question is whether to use external technical assistance in the system-development process. Actual experience with the use of consultants is mixed. Consultants can be a source of expertise not available locally and also can augment the system-development work force on a temporary basis. Much depends on the client’s ability to define clearly the work products expected from technical consultants as well as the delivery schedule. In addition, the contracting agency must have the capability of managing the contract and monitoring the contractor’s performance.

With respect to project management in general, several observations and recommendations can be made. First, the project planning and management techniques and the programming technique mentioned earlier can be of assistance in system development. The steady flow of products resulting from such techniques makes monitoring the project easier. Moreover, parts of the system can be tested incrementally, in contrast to a massive testing effort at the end of the development phase. The techniques also give managers, system-design personnel, and users a clear picture

of the system as it evolves, thereby making it easier to spot errors and omissions and to suggest modifications and improvements.

System-implementation activities revolve around making sure that the system performs the way it was designed to. The information that the system receives must be converted into a form that the system can use. The chief recommendations that can be made in this regard are (1) to use existing data if practicable, since data collection is very time-consuming and costly, and (2) to take all feasible steps to ensure that only accurate data are stored in the system.

User orientation is a major activity during the system-implementation phase. User manuals are prepared, and orientation and training sessions are held.

5.5

ACQUIRING COMPUTING CAPABILITIES

Having cadastral records in computer-readable form offers innumerable benefits and is now feasible even for the smallest counties. Computers can reduce the time spent on such mechanical processes as producing reports and documents, sorting records, and aggregating data. They can speed mathematical calculations and make possible statistical analyses that could not be feasibly done manually. Increasingly, computers are being used to produce maps and other graphic displays. In addition, computerized diagnostic checks can enhance the quality of data.

Quite naturally, cadastral record managers often are concerned with evaluating and acquiring or upgrading computer hardware, software. or both. The range of considerations that enter into the decision-making process is quite broad, and only major points can be touched on here. Managers should turn to experts for the additional experience they need. One way to keep abreast of developments in the field is to consult the ACM Guide to Computing Literature (Association for Computing Machinery. annual).

An early step in acquiring computing capabilities is to develop a general strategy (Donaldson, 1978). Unless one is constrained to use computing machinery currently on hand, software needs should be evaluated first, and hardware needs should be evaluated in the light of requirements imposed by the software and the amount of data to be manipulated.

A general issue is processing mode. Formerly most processing was done in a batch mode, which offered some processing efficiencies. However, the trend is toward on-line processing, in which files are updated on a record-by-record basis at the instant the user chooses. This is accomplished through terminals, and the system must be designed to accommodate a variety of inquiry, update, and other jobs being performed more or less simultaneously.