3

Characteristics of Adolescence That Can Affect Driving

Learning to drive is an important rite of passage, particularly in the United States, where limited public transportation in many areas can mean that the ability to drive is a key to independence. Teenagers who cannot drive may have to depend on their parents and others for mobility, and this can limit their options for employment, restrict their participation in school and community activities, and influence their social lives. Teenagers are generally eager to learn to drive—76 percent of young people age 15 or younger, for example, report that they are “very” interested in getting a license as soon as they can, David Preusser noted. Parents who may have spent many hours chauffeuring their children to and from activities may be eager for their teens to drive. But even though most teens want to drive and feel ready to handle the responsibility, a close look at their cognitive, social, and emotional development suggests that readiness to drive safely is not likely to occur automatically by the age of 16. The workshop addressed several aspects of adolescent development, with a focus on the features of this phase that are likely to have the greatest bearing on driving skills.

DEVELOPMENT— HOW ADOLESCENTS DIFFER FROM ADULTS

A variety of affective factors influence teen decisions and behaviors, as Ronald Dahl explained. He began with what he called the health paradox

of adolescence. Although adolescence is the healthiest period of the life span physically, a time when young people are close to their peak in strength, reaction time, immune function, and other health assets, their overall morbidity and mortality rates increase 200 percent from childhood to late adolescence. Many of the primary causes of death and disability in these years—which include crashes, suicide, substance abuse, and other risky behaviors—are related to problems with control of behavior and emotion.

The reasons why adolescents can have difficulty controlling their emotions and behavior are complex, and a thorough overview of decades of research on adolescent development was beyond the scope of the workshop.1 Instead, the focus was on identifying key insights that may have particular relevance to the problem of teen crashes and to use these insights as an entry point for exploring possibilities for improving the effectiveness of teen driving safety efforts.

A complex web of physiological, psychological, and environmental conditions contributes to an increase in impulsivity in adolescents and influences both decision making and regulatory functions that affect driving as well as other adolescent behaviors. Indeed, a hallmark of this stage of life, not only in humans but also in other mammals, is the tendency toward increased risk-taking and novelty-seeking, as well as an increased focus on social context (Romer, 2003; Lerner and Steinberg, 2004). These characteristics foster the development of independence at the same time that they increase young people’s exposure to risk, and it is important to note that they involve both natural and adaptive processes, even though they can have very negative results.

As might be expected, the onset of puberty plays an important role. As puberty begins, changes in the endocrine system can affect drives, motivation, mood, and emotion. This period is characterized by increased emotional intensity and changes in romantic motivation. It is associated with increases in risk-taking, novelty-seeking, and sensation-seeking, as well as an increased focus on social status. These attributes can have significant

effects on driving behavior. Moreover, cognitive development occurs on an unrelated trajectory that is not complete until the early 20s—long after puberty is over. Thus, the capacity for planning, logical reasoning, and understanding the long-term consequences of behavior are far from fully developed during the period when most young people in America are beginning to drive.

Another key difference between adolescent and adult brains is in their capacity to manage multiple tasks at once. The capacity known as executive function, which is the key to judgment, impulse control, planning and organizing, and attention—or, as it has been called, the CEO of the brain— is situated in the prefrontal cortex, which is still under construction during the teen years. In the absence of stress and distraction, most teens function well, but this regulatory capacity can be easily overwhelmed by strong emotion, multitasking, sleep deprivation, or substance abuse (Luciana et al., 2005). The particular risks posed to teen drivers by extra passengers, music, cell phones, and other sources of stimulation or distraction begin to make sense when this aspect of teen development is understood. Other specific perspectives on adolescents offer further insight.

ADOLESCENT DECISION MAKING

Adolescents also differ in significant ways from adults in their approach to risk and decision making, as Julie Downs explained. She began by enumerating the primary factors that affect decision making in general:

-

knowledge of risks,

-

appreciation of the potential trade-offs between risks and benefits,

-

assessment of short- and long-term expectations,

-

focus on the most likely outcomes, and

-

perceived alternatives to taking the risk.

The conventional wisdom about teenagers’ risk-taking is that they both fail to appreciate the risks that face them and wrongly perceive themselves as invulnerable to risk in general. In fact, however, teens do not believe they are invulnerable. Their perceptions of many risks are fairly accurate, and they actually tend to rate their overall risk of premature death as far higher than it actually is. For example, while teens can estimate the likelihood of being arrested (less than 10 percent) or, among girls, becoming pregnant in the next year (6 percent) with fair accuracy, they estimate their risk of dying

in the next year at 18.6 percent, while the actual risk is 0.08 percent. Teens can be overly optimistic in other areas. Nearly 73 percent, for example, predict that they will have a college degree by the age of 30, while only 30 percent actually achieve this goal.

The misperception that affects teens’ driving, which they share with adults, is a tendency known as the optimistic bias, or overconfidence in their own control over risk. For example, while smokers of all ages know that smoking puts them at risk for lung disease and death, most believe their own risk is less than that of a typical smoker. What compounds this problem for teens, however, is their lack of understanding and inaccurate thinking about cumulative risk. In other words, teens correctly assess the risk associated with any single car trip as relatively low. However, each time the teen takes an uneventful drive, his or her perception of the riskiness of driving goes down while perception of the benefits goes up. While a teen driver may still acknowledge the overall risk, even after acquiring months of experience, he or she perceives a decline in the risk posed by any single driving trip. The result is a teen who believes he or she can handle hazardous situations, is overconfident of his or her driving skills, and is decreasingly vigilant about safety. Since the teen is also less experienced and competent at the wheel than the average adult, the optimistic bias is particularly hazardous for teen drivers.

THE IMPORTANT ROLE OF PEERS

Adolescents are intensely attuned to social interactions with their peers, and Sara Kinsman and Joseph Allen provided two perspectives on the key ways in which these relationships influence behavior and increase risks for young drivers and their passengers. Teens are focused on their peers for good reason, Kinsman noted, and she argued that learning to negotiate peer relationships is the most important developmental task that adolescents must accomplish. To complete the transition to adulthood, teens must learn to get along with, work with, live with, and care for their peers, and these relationships are integral to success in almost every aspect of life.

Kinsman explained that the collective process through which teens create their own culture is an important part of this task—and that it is not simply a matter of rebelling against adult norms and authority. Reciprocity is an important part of this process, so it is important for young people to demonstrate that they are a part of the collective endeavor by emphasizing ways in which they are like other members of the group. Issues of status,

social groupings, and adherence to norms are all integral to this process. Because these relationships and the teen’s place in his or her peer group are so important developmentally, the peer group can have as much influence on behavior as individual characteristics, such as gender, socioeconomic status, and family influences.

Peer interactions often make risky behaviors more likely. Kinsman presented data from a study by Mokdad et al. (2004), which demonstrated that teens typically initiate dangerous behaviors with peers—indeed, approximately 25 percent of all U.S. deaths are the result of activities that are initiated with peers during adolescence.

Joseph Allen amplified this point with a discussion of teens’ attitudes toward deviant or risky behavior. He noted, as Ronald Dahl had as well, that teens are more prone to thrill-seeking than adults are, and that their quest to seem mature and to increase their autonomy can lead them to take risks. Rates of deviance, Allen explained, increase dramatically beginning at about age 11, peak at around age 16, and then drop off gradually over the following 10 to 15 years. Several factors combine to make all teens vulnerable to negative peer influences. Teens’ great need for social acceptance combines with inexperience in handling pressure from peers. Moreover, Allen explained, popular teens are more likely than so-called average teens to engage in risky behavior at younger ages, to increase that behavior quickly, and to sustain it (Allen et al., 2005). Moreover, as Kinsman noted, popular teens are socially adept and have a skill set different from that of others. They have a particularly strong influence on youngsters who are social followers—eager to improve their social status by association with more popular peers. Thus, in many cases, the teens in leadership positions are more likely to instigate risky behavior—but teens who are struggling socially may be more susceptible to negative influences.

Driving—the single activity that involves the greatest risks for the largest number of teens—can play an important role in peer interactions. The ability to drive one’s friends around can allow teens to pursue important social goals, for example, by allowing them to demonstrate maturity, return favors that others have offered, enhance their status, reinforce membership in a group, or host the social event that a group car trip can be. The key point in terms of driving safety is that when driving with peers, teens are undertaking two separate, challenging, and complex tasks: they are keenly attuned to the behavior of and interactions among their peers while also operating the vehicle and attending to road and traffic conditions. From a developmental perspective, Kinsman argued, it is unrealistic to expect teens

to tune out their peer passengers and give their full attention to the task of driving.

Allen described the situation in a car full of teenagers as “the perfect storm,” because four elements come together in that situation: peers who may value risky behavior, teens who need social acceptance, the likelihood that the riskiest teens will be the loudest, and all teens’ relative lack of immunity to peer pressure. At the same time, the teen who is driving cannot easily see the faces of the passengers, which increases the stress of staying attuned to the social dynamics, yet it is the driver who is primarily responsible for the safety of the situation.

Allen argued that it may be possible to harness peer influences in positive ways if strategies can be found to link responsible driving with attributes or rewards that teens value. For example, teens value both self-confidence and skill, and they also value money and material goods. Thus, a program that took these values into account by offering rewards for demonstrating responsible driving skills in specific ways—such as driving for a certain period without any violations or passing a series of tests—would have the benefit of meeting teens on their own terms.

SLEEP DEPRIVATION

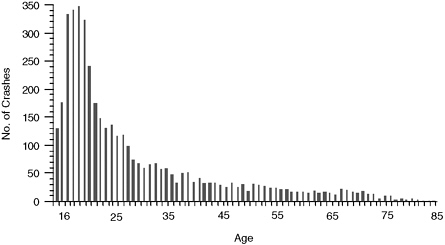

Another way in which teens differ from adults is in their need for sleep—and in the factors that work against their getting enough sleep. Alertness is key to safe driving at any age, and adequate sleep is an important contributor to alertness and the capacity to focus on all the details a safe driver must monitor. Adolescents are chronically short on sleep, as Mary Carskadon explained, and the result is more crashes in this age group. Figure 3-1 shows the age distribution for crashes caused by drivers who fell asleep at the wheel, with a sharp peak in the teenage years.

High school students need approximately 9 hours of sleep per night, but generally get between 7 and 7.5 hours. College students also get more than an hour less per night than the 8.4 hours they need. Both biological factors and the circumstances of young people’s lives play a role in this chronic sleep deficit. During the adolescent years, young people’s sleep needs increase and their circadian (sleeping and waking) rhythms also change. The net result is that teenagers have a biologically driven tendency to stay up later at night and sleep longer in the morning, at the same time that their daily sleep requirements increase over what was needed in late childhood.

FIGURE 3-1 Age distribution of drivers in fall-asleep crashes.

SOURCE: Reprinted, with permission, from Pack et al., 1995. Copyright 1995 by Elsevier.

While these processes are taking place, other factors are working against sleep for many teens. In the same period when parents are gradually relinquishing control over teens’ daily lives, particularly bedtime and other daily functions, both academic obligations and social opportunities are generally increasing—and giving teens reasons to stay up at night. Moreover, a 2006 National Sleep Foundation study found that 97 percent of adolescents have at least one electronic device in their bedroom (e.g., television, computer, Internet access, cell phone, music player), so the array of stimulating activities that might keep them awake is far more diverse than it was a generation ago (National Sleep Foundation, 2006). The same study showed that the presence of four or more electronic devices in the bedroom is associated with a loss of 30 minutes of sleep per day, on average.

Adolescents stay up too late, but they are also required to wake up quite early for school. School bus schedules as well as pressure to end the school day in time for after-school sports practices and other activities have generally caused school officials to set early start times for high schools. Many communities have attempted to address the tension between these pressures and adolescents’ natural impulse to sleep later in the morning. Some have adopted later start times, and efforts to make this change are ongoing in many communities. However, with many teens staying up until

midnight and well beyond, an extra 30 to 60 minutes of sleep in the morning—all that most communities have been able to muster—may not be enough to address the problem.

The effects of sleepiness on driving are striking. After 17 hours awake (for example, a teen who woke up at 6:30 a.m. and is still socializing at 11:30 p.m.), a teen’s performance is impaired to the same extent that it would be with a blood alcohol content of 0.05 percent. Driving home from the prom at 6:30 in the morning (after 24 hours awake), a teen’s driving would be impaired as much as it would be with a blood alcohol content of 0.10 percent. Apart from late-night driving and unusual circumstances that cause extensive sleep deprivation, teens are at their sleepiest in the morning, and the rate of fall-asleep crashes for 16- to 25-year-olds confirms this, peaking between 6 and 8 in the morning (Pack et al., 1995).

The bottom line, Carskadon concluded, is that many adolescents and young adults are not getting sufficient sleep to meet the needs of their growing bodies, with the result that they are at increased risk of crashing when they drive.

THE SOCIAL CONTEXT OF TEEN DRIVING

The cognitive and social development that takes place during adolescence interacts with individual personality traits, driving experience and ability, characteristics of the vehicle, and the roadway environment to influence driving behavior and safety, as Susan Ferguson pointed out. Other individual factors may be particularly relevant to driving as well. David Preusser noted that there is a body of literature dating back to the 1960s on the relationships between juvenile delinquency, dropping out of school, and poor academic achievement, as well as socioeconomic factors, family structure, and risk behaviors in adolescence and crashes (Preusser, 1995).

This initial sketch of key characteristics of adolescence points to prospects for significantly improving driving safety for teens by building interventions that draw on the relevance of the social context of teen driving and the cognitive and social development processes that occur during these years. Moreover, most of the attention in research on traffic safety has focused on risk factors, but adolescents also have many characteristics that can work in support of safety. Prevention strategies developed in other public health contexts that draw on young people’s many strengths may well be applicable to the problem of teen crashes.

The extent to which the characteristics of adolescents and their developmental processes are not adequately taken into account in driver’s education, licensing, and supervisory practices for young drivers was a persistent theme throughout the workshop. The next chapter explores current and potential strategies that might contribute to prevention efforts.