4

Strategies to Improve Safety

Policies, laws, and other strategies can clearly affect teens’ driving behavior and their safety. Data presented on the effects of graduated driver licensing and minimum drinking age laws, for example, demonstrate that injury and fatality rates are not immutable, despite the fact that, as Robert Foss pointed out, human beings are difficult to change. This chapter first describes strategies already in place and then explores additional strategies, such as greater parental engagement in supervising teen drivers, that offer potential to significantly increase safe driving behaviors among teens.

CURRENT STRATEGIES

At present, two key tools are used to improve the safety of teen drivers: driver education and the legal structure of testing and licensure.

Driver Education

Driver education programs, first developed in the 1930s, became increasingly widespread in the United States between the 1940s and the 1970s, according to Richard Compton, who provided an overview of the history of this crash prevention strategy, research on its effectiveness, and current trends. A basic model of 30 hours of classroom instruction, often given at public high schools, plus six hours of instruction behind the wheel

of a car was established in most states. In the intervening decades, however, these programs did not reduce crash involvement among beginning drivers. Recognizing that no differences emerged in the crash records of driver education graduates and those of equivalent groups of beginning drivers who learned to drive without formal education, many states scaled back funding for these programs. From a peak in 1976, when 3,200,000 students in 17,000 public schools took driver education courses, the number has steadily declined. In 1981 the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) dropped driver education from its list of priority programs; however, many states still require formal training as a condition of licensure prior to age 18.

The goals for driver education classes are generally straightforward— to teach young people the rules of the road, the basic skills they need to control the car, and safe driving practices, such as defensive driving and risk assessment. Research conducted during the early years (1940 through 1960) generally yielded the positive finding that the programs produced safer drivers. Later researchers, however, cast doubt on the findings of earlier studies, finding that their methodology did not take into account significant differences between those who did and did not take the courses, for example. Such differences might include individual motivations and safety mindedness, as well as larger demographic differences related to socioeconomic status. Moreover, newer studies indicated that the availability of driver education programs (in states that require teens who wish to be licensed before age 18 to successfully complete such a program) provided the opportunity for young people to get a license before age 18. When more drivers under 18 are licensed, more teens are at risk of crashing and more crashes occur.1 Finally, a large-scale 1983 NHTSA state-of-the-art study (the “DeKalb study”) (Stock et al., 1983) used randomized assignment to evaluate the impact of the driver education curriculum, and the results did not support the effectiveness of driver education in reducing crash rates. In response to that study, governmental support for driver education declined (Mayhew and Simpson, 1997; Young, 1993).

Driver education is not viewed as a lost cause by safety experts, however. Suggestions have been made that these programs could address safety

skills in new ways, by addressing teens’ tendency toward risk-taking and overconfidence and by increasing parental involvement, for example. Workshop participants emphasized the importance of introducing driver education within a broader framework of graduated licensing, making distinctions between developing the manual skills that are necessary to operate a complex vehicle and acquiring the expertise and judgment to recognize hazards and to exercise caution when driving under risky conditions. While traditional programs tend to emphasize the former, the latter area remains unaddressed in the curricula of many driver education programs. In exploring the merits of driver education, Compton noted that NHTSA is reviewing opportunities for improvement and is considering new curriculum guidelines as well as standards for teachers. In addition, NHTSA is developing a national and international review to identify instructional tools, training methods, and curricula that are consistent with best practices in selected states and other countries.

A related issue is the relatively recent development of private courses that focus on enhancing driving skills in hazardous conditions. Often taught by former race car drivers or others with experience in “extreme” driving, these courses may use technology to simulate such hazards as slippery roads, or they may present teens with actual hazards in safe settings, and allow teens to learn skills for handling them. While these programs are appealing to many parents, few data are available to demonstrate their effectiveness. Indeed, a few studies have shown that the crash rate for young drivers, especially young men, who receive skid training is higher than for those who do not (Jones, 1993; Glad, 1988). Several participants mentioned that taking such a course might actually foster overconfidence in some teens, who might demonstrate show-off behavior and exercise less caution because they believe their new skills will allow them to handle any hazard (Williams, 2006). On one hand, this concern is consistent with the recognition that teens may seek out novel opportunities to try out new skills—or they may perceive that they have more control over the vehicle than they really do—thus increasing their exposure to crashes. On the other hand, experience with certain types of hazards may be of real benefit to many teens. Continued use of similar programs to train police officers and other adults who need these skills suggests that some aspects of these programs merit further exploration to determine their potential benefits for teen drivers.

Licensure and the Law

Driver education, regardless of its content, has not been mandatory for all teens, but state laws affect all teens who want to drive legally. Anne McCartt provided an overview of legal and regulatory approaches to reducing teen crashes and indicated that strong laws, combined with well publicized enforcement, have been the most effective measures in changing teen drivers’ behavior.

One target of state law has been driving under the influence of alcohol. As McCartt explained, teens are actually somewhat less likely than adults to drive while impaired by alcohol, but their crash risk is greater when they do so, particularly when their blood alcohol content (BAC) is low or moderate. To combat this problem, all U.S. states have now made the minimum legal drinking age 21, and all have adopted “zero tolerance” laws that prohibit teens from driving with a level of alcohol above 0.02 percent in their systems. These laws have significantly reduced the rates of fatally injured drivers ages 16 to 19. For example, the percentage of fatally injured drivers with BACs of 0.08 percent or higher has fallen from 51 percent in 1982 to 23 percent in 2003. However, McCartt noted that progress has stalled in recent years, and she argued that increased enforcement is needed to further reduce alcohol-related teen crashes.2

The other major strategy that states have increasingly adopted involves changes in testing and licensure for new drivers. Standard testing for a license to operate a motor vehicle assesses knowledge of traffic safety rules and operation of the vehicle. Students may prepare for the written and road tests by memorizing information about speed limits and traffic rules and by practicing parking or navigating intersections. The tests generally do not assess the capacity to handle more complex scenarios, nor do they require students to identify potential hazards or to address unexpected circumstances, distractions, or peer pressures that are common features of normal driving conditions.

Recognizing the high risks teens face in their first months on the road and the important opportunity that testing and licensure offer to shape

their driving behavior, many states have adopted some version of graduated driver licensing (GDL). As the name implies, GDL is a means of slowing down the process of obtaining the license, controlling the circumstances under which teens drive while they are learning, and thus increasing their exposure to higher risk conditions (such as nighttime driving and driving with teen passengers) in a gradual, controlled way.

Typically, the GDL process has three phases—an extended supervised practice stage for teens possessing learner’s permits, a provisional licensure stage during which restrictions are imposed, and then full licensure. Many states have adopted specific practice requirements for the first phase, such as 30 or 40 hours of supervised driving, to supplement any driver education classes teens might take. The provisional license stage includes restrictions on teen exposure to circumstances that are known risk factors.

A significant number of states have adopted elements of GDL in the past 10 years (Table 4-1), and many states continue to update their requirements to include additional features.

As Allan Williams noted, however, no single state has adopted all of the features of GDL that are viewed as constituting best practice. On one hand, in some states, parents or other groups have successfully resisted efforts to implement GDL provisions, opposing proposals to extend the supervisory period for newly licensed youth. On the other hand, smaller numbers of states have more recently increased restrictions on night driving and carrying passengers, increased requirements for supervised driving, or banned the use of cell phones while driving.

The benefits of GDL are clear, as McCartt and others emphasized. The combination of limiting driving in hazardous situations, increasing the amount of supervised practice driving, and delaying full licensure seems

TABLE 4-1 State Adoption of Licensing Requirements

|

|

1995 |

2006 |

|

Minimum learner’s permit age 16 or older |

8 states |

9 states |

|

Learner’s permit for at least 6 months |

0 |

42 |

|

30 or more hours of certified driving |

0 |

30 |

|

Night driving restriction once licensed |

9 |

45 |

|

Passenger restriction once licensed |

0 |

36 |

|

SOURCE: Reprinted, with permission, from Insurance Institute for Highway Safety (2006). |

||

TABLE 4-2 Evaluations of Graduated Licensing Programs in the United States

|

|

Age Group |

Crash Reduction Rate (%) |

|

California |

15-17 |

0 |

|

California |

16 |

17 |

|

California |

16-17 |

28 |

|

Florida |

15-17 |

9 |

|

Michigan |

16 |

29 |

|

North Carolina |

16 |

34 |

|

Ohio |

16-17 |

23 |

|

Wisconsin |

16 |

14 |

|

SOURCES: California ages 15-17: Masten and Hagge (2004); California age 16: Cooper et al. (2004); California ages 16-17: Rice et al. (2004); Florida: Ulmer et al. (2000); Michigan: Shope and Molnar (2004); North Carolina: unpublished data, available from Rob Foss at Highway Safety Research Center; Ohio: Ohio Department of Public Safety (2001); Wisconsin: Fohr et al. (2005). |

||

to target key risk factors associated with teen driving. One study has shown an 11 percent decrease in fatal crashes among 16-year-olds in states that have some form of GDL, with larger decreases occurring in states that have the most comprehensive programs (Baker, Chen, and Guohua, 2006). Evaluations cited by McCartt showed marked reductions in crash rates for 16- and 17-year-olds following the adoption of GDL in several states (Table 4-2).

As with the drinking laws, however, McCartt and others noted that GDL programs would be more effective if enforcement—both by parents and law enforcement officials—was tougher. GDL in particular depends on parents to enforce many of its provisions, both to supervise their children for the required number of driving hours and to monitor their adherence to passenger and night-driving restrictions. Moreover, while the value of traditional driver education has come into question, ways to improve it and link it to GDL provisions have not yet become a primary focus for states.

Several participants mentioned the broader role of law enforcement policies, the potential impact of teens’ perception that laws are being enforced, and the role of the insurance industry as areas that deserved further attention in the development of prevention strategies to reduce teen crashes.

The time allotted for the workshop did not provide opportunity to adequately address the potential for these groups to contribute to proactive improvements in safety. Other strategies with potential were addressed in greater detail and are described below.

STRATEGIES WITH POTENTIAL

While GDL and minimum drinking age laws have led to reductions in risky driving and crashes, teen crash rates remain unacceptably high. Persistent concern about the issue is now stimulating a search to identify existing strategies that are not being exploited to their full potential. In addition, new technical interventions now offer the potential to protect novice drivers—and all drivers—in previously unimaginable ways.

Parents

The success of GDL has focused attention on the role that parents can and must play in the critical learning period for teen drivers. As Bruce Simons-Morton explained, parents influence teens’ actions during this period in a variety of ways, for good or ill; their intentions are good but the outcome is mixed. Parenting practices, parents’ knowledge, and the relationship between parents and their children all contribute to teenagers’ acquiring safe driving practices. Parents can play a critical role, but in many cases they don’t know what they should be doing to help their children drive safely—or how best to do it. Moreover, policy makers and others frequently do not take advantage of the opportunities they have to help parents become effective driving coaches and supervisors while their children are novice drivers.

Taking the parent-teen relationship first, Simons-Morton called attention to the familiar model of authoritative parenting that psychologists advocate, in which parents make and enforce rules but also are supportive, flexible, and responsive to their teens. If parents are involved in their children’s lives, monitor their children’s behavior, convey their expectations clearly, impose consequences, and maintain open communication and a sense of mutual trust, outcomes are likely to be better than if they do not.

However, even when these conditions are all in place, a variety of factors pushes both teens and parents to favor driving privileges. Parents as well as teens can be naïve about the actual risks of crashing. Parents may be satisfied with the teen’s mastery of the mechanical skills of managing the

vehicle and fail to appreciate the importance of other safe driving skills, such as hazard detection, risk assessment, and anticipatory behaviors. Both parents and teens are subject to social pressures in favor of teen driving, and at the same time, parents may be eager to stop driving their teens around. Teens are generally eager to drive, and parents want to give them the gift of independence.

Simons-Morton summarized the more specific ways in which parents can influence teen driving and their potential effects on safety. Two things they can do have demonstrated safety benefits: delaying permission to test for a driving license and controlling access to the vehicles and driving circumstances (such as night driving and carrying passengers) for novice drivers. When it comes to drinking and driving, the role of parents is complex, and Simons-Morton noted that the example parents set may far outweigh other messages they attempt to send. Moreover, parents may believe they have explained what their children should do if they find themselves in a situation that involves drinking and driving, but teens report that they are not sure.

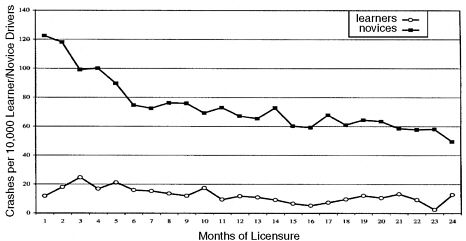

Finally, supervised practice driving, required in increasing numbers of state GDL programs, has significant potential, but it has not yet demonstrated safety effects (such as changes in crash or mortality rates) on its own in the United States, perhaps because parents have been offered little guidance on how to make use of this time. Another issue with supervised driving is that when parents are in the car, they tend to have the primary responsibility for safety and risk assessment, even if the teen is driving. They are scanning for hazards, coaching and guiding the teen, and may be making or influencing many of the decisions about acceptable conditions, avoiding dangerous intersections, and so forth. Thus, once the teen drives alone, the initial period of practice driving has not necessarily prepared him or her to anticipate hazards. There is a need to identify specific components of supervised driving, Simons-Morton explained, that can be tested experimentally and are associated with increased knowledge and behavioral improvements among youth. Developing driving proficiency requires experience, so the key is to allow learning drivers to gain that experience in circumstances that are relatively safe. Figure 4-1 compares crash rates for novice drivers who do and do not learn under supervised circumstances.

A program called Checkpoints, developed by researchers at the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, provides a structure in which parents can work with their teens to reduce risk conditions during the first 12 months of driving. The program uses a combination of

FIGURE 4-1 Crash rates by license status and months of licensure.

SOURCE: Reprinted, with permission, from McCartt, Shabanova, and Leaf (2003). Copyright 2003 by Elsevier.

tools, including persuasive communications, such as videos and newsletters, written agreements between parents and their children, and limits on high-risk driving privileges. A controlled study, in which some families participated in the Checkpoints program and others received comparable driving safety materials but not all of the Checkpoints interventions, showed that Checkpoints families imposed and maintained significantly more restrictions on their teenagers’ driving. However, the study sample was not large enough to show ultimate effects on crash rates.

The Checkpoints program is based on the goals of changing both parents’ and teens’ perception of their risk, as well as their expectations regarding reasonable limitations—in order to decrease risky driving, traffic violations, and crashes. Although initial results for Checkpoints are positive, Simons-Morton noted, additional research on changes in novice driving performance over the first 18 months of driving, on the nature and effects of supervised driving, on other ways to deliver support and improve parental management, and on ways to incorporate findings about the process of learning to drive into driver education and testing and licensure programs would be of great benefit.

Richard Catalano provided an additional perspective on the role of family influences with a framework that is part of a larger social development approach to risk prevention. Key risk and protective factors that affect adolescent behavior may be evident long before youngsters reach the

teen years, he explained, and targeted strategies can be used to improve outcomes for teens. Catalano described a study called Raising Healthy Children (RHC), in which five matched pairs of elementary schools were randomly assigned to receive either a prevention program based on the social development approach or a control condition.

The risk and protective factors addressed in the RHC program are listed in Box 4-1. Such interventions as teacher and parent workshops, in-home services, and summer and after-school programs were offered to children as young as first grade to focus on such goals as developing social and other skills, addressing school and family management problems, and promoting prosocial behaviors. Brief family sessions were offered to families at critical transition points, including the transition from middle to high school, the transition out of high school, and the transition to driving.

|

BOX 4-1 Risk and Protective Factors Risk Factors

Protective Factors

|

Based on the proposition that good parenting reduces poor driving, the sessions designed to improve driving safety had specific objectives. In the first session, parents and teens discuss trying new things in adolescence and examine their perspectives on risk-taking. In this discussion, parents and teens seek to understand the current driving laws and the risks of driving while young and inexperienced. In addition, teens practice skills for making healthy choices, focusing on motivations and consequences, while parents demonstrate the ability to coach their teen in using decision-making skills to reduce conflict and to establish effective communication. The session concludes with an exercise in which parents and teens strive to integrate this information and skills into guidelines and expectations for driving.

The second session had four goals:

-

parents display competence in using communication and anger management skills with their teen;

-

teens learn how to handle crashes, dead batteries, flat tires;

-

parents and teens implement a family driving contract; and

-

parents and teens apply a “guidelines, monitoring, and consequences” approach to driving-related difficulties and conflict (demonstrate knowledge and use of effective consequences, identify ideas for recognizing teens’ positive driving behavior).

Bearing in mind that the program was designed to address a broader range of risks than just those associated with driving, the program has demonstrated some promising results. For example, families receiving the intervention were four to six times more likely than the control families to report that they had established a driving contract. Teens in the families receiving the intervention also reported that they drove less frequently under the influence of alcohol or rode with peers who had been drinking.

While participants agreed that more study of effective means to harness the potential of parents and family dynamics in improving teens’ driving safety is needed, the potential benefits seemed clear.

Health Care Providers

Health care providers are not all doing their part to provide prevention messages to adolescents and their parents, according to specialist in adolescent and young adult medicine Lawrence D’Angelo. He indicated that this

gap is notable, especially in light of evidence that this kind of counseling has had positive effects in other areas, such as reducing smoking. Driving safety is not a prominent topic during medical students’ training in pediatrics, he explained. Consequently, even experts in adolescent medicine (who receive specialized training and certification) report providing counseling about alcohol, drugs, and/or automobiles only 82.5 percent of the time during their annual examinations of adolescent patients. Specific threats to adolescent health, such as the risks of having passengers in the car and night driving, are mentioned far less frequently (12 and 7 percent, respectively). Indeed, D’Angelo pointed out, only 60 percent of adolescent specialists know whether the state has a GDL law, and the percentage was only slightly higher among those with adolescents in their own household (77 percent).

Another health care-based strategy that has not been well explored, participants pointed out, is that of pursuing individual characteristics that may increase driving risk. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, type 1 diabetes, and substance abuse are just a few of the factors that might put an individual teen at increased risk when driving. Teens with these problems are not routinely counseled about how their diagnoses may affect driving. Yet patients with other health risk factors, such as those for cardiovascular disease, are routinely identified and patients are counseled on ways to minimize negative outcomes.

Guidelines for health care providers, innovative ways of delivering counseling to youth and their families, and additional research that encompasses a broader health agenda for adolescents were all mentioned as viable ways to encourage providers to address teen driving risks. The role of public health agencies in addressing the risks of teen driving, as well as opportunities to promote responsible driving practices, were identified as particularly deserving further attention.

Technology

Without a doubt, intensified and improved efforts using existing strategies could yield further improvements in safety, but they offer only partial solutions to the fundamental problem—allowing young people to learn driving skills and gain experience behind the wheel without risking their lives. Many of the strategies already discussed address ways in which adults might either persuade or compel teens to behave differently or improve the training they receive or the quality of their practice time behind the wheel.

Technology offers a very powerful companion strategy with significant potential to make driving safer not just for novices but for all drivers. Max Donath, Wade Allen, and John Lee described some of the technological innovations with particular promise.

Technology in the Car

Donath began by noting a few reasons why technology offers significant opportunities to reduce crash and fatality rates. Measures to increase seat belt use, for example, have had a significant impact on survival rates, but this improvement increased markedly as the policies shifted from voluntary interventions to mandatory requirements. When seat belts were first introduced in large numbers of cars in the 1960s, for example, they were used less than 25 percent of the time, and they were generally used by the lowest risk drivers. State laws requiring the use of seat belts helped to boost implementation rates, but large proportions of the driving population who were at higher risk of crash involvement did not tend to use the safety restraints until enforcement provisions were legally mandated. At present, teenage boys continue to be one of the groups least likely to wear seat belts (Transportation Research Board, 1989, 2003).

Other, more complex technologies can influence other driving behaviors, Donath noted, in one of three ways.

The first is forcing behavior, which involves using technology to make it impossible to operate the vehicle in certain circumstances. For example, a seat belt interlock can prevent the car from starting unless all occupants have engaged their seat belts. An alcohol ignition interlock feature requires the driver to puff into a tube connected to a BAC sensor, which engages the interlock if a preset BAC threshold is breached. Intelligent speed adaptation (ISA), in which a system using a global positioning system (GPS) and a digital road map can prevent a driver from exceeding the posted speed limit, is another example of forcing behavior. ISA may also use the second of the three approaches, driver feedback, by signaling to the driver the need to reduce speed. Some versions of ISA are even designed to adapt warnings to such factors as road and weather conditions, traffic congestion, and time of day. Interlock systems can be installed when cars are manufactured, so new vehicles might come with “smart” keys that identify drivers, for example, with the possibility of programming different restrictions for different members of a family.

Driver feedback is a system for providing real-time warnings of poor

driving, hazardous conditions, or other potential risks. For example, this technology might recognize curves in the road or departure from a lane and alert the driver to make corrections to speed and steering. This type of technology could also be used to control misuse of entertainment systems, which can be very distracting for teen (and other) drivers.

Reporting behavior is a system for collecting data about driver performance that can either be saved for later review by parents or other driving supervisors or transmitted in real time so that parents have the option to intervene. The driving “report card” might include data on speed, acceleration, braking, throttle use, and time and location of the trip, which can allow parents to supervise their teen’s driving even when they are not physically present. Such programs may be initiated through novel features, such as cell phones or web sites that use GPS to report phone or vehicle location, speed and direction of travel, and time of day on a routine basis.3

John Lee described other kinds of driver supports that can enhance safety, some of which are already available and some of which will be soon. Forward collision warnings, road departure warnings, and steering assist devices are among the adaptive technologies that can either warn the driver of a potential risk or actually intervene to minimize or prevent it. He predicted that the market for such devices could reach $10 to $100 billion by 2010.

While many technical innovations offer promising approaches to prevention, several participants observed that new interventions and technology need to be carefully evaluated before they are widely adopted. Eagerness to reduce teen driver crashes can too easily encourage the adoption of new devices based on a perception of potential benefits rather than a rigorous assessment of their actual effects and risks. Although some technical innovations may offer superior ways to teach driving skills and prevent some impaired drivers from operating their vehicles, the overall effects of technology on changing attitudes among the youth population about risk and responsible driving may be very small. Drivers may also adapt to new technologies in unexpected ways, taking other risks that lessen the intended value of the new devices. In addition, public resistance to forced behaviors or technical overrides should not be underestimated.

Technology in Driver Education

As discussed above, traditional driver education has focused on teaching skills, driving practices, and the rules of the road. Computer-based instruction makes it possible for the objectives of driver education to include not only a more complex conception of driving skills—encompass-ing perceptual, psychomotor, and cognitive skills—but also attitudes about driving and risk-taking and a wider range of knowledge about the challenges of driving. As Wade Allen, who provided an overview of the potential of this technology, explained, computer-based instruction also offers practical advantages as well—it can be administered on the web, for example, and can be provided consistently and easily by school districts and driver education schools.

The primary advantage of computer-based instruction is that it can use scoring to motivate and encourage students and to focus attention on the criteria for successful completion of the course. As it does in other contexts, computer-based instruction allows novice drivers to practice handling hazardous situations without risking their lives. Students can experience roadway and traffic hazards, even crashes, in real time and practice situational awareness (awareness of the surrounding situation and potential risks) and decision making under stress. Scoring for practice sessions can instantly indicate the consequences of driver decisions. Computer adaptive technology could allow the program to focus on a student’s weaknesses, allowing follow-up practice to reinforce learning from mistakes.

Computer-based instruction can be delivered on a desktop computer (the least expensive model), in a console simulator or a more complex display system, or by means of a portable computer installed in a vehicle that is equipped with a virtual reality headset (the car’s wheels are placed on turntables so the learner can operate the steering wheel). Although the costs increase significantly with the complexity of the hardware, the face validity—that is, the extent to which the simulated experience resembles a real-life experience—is likely to correspond to the sophistication of the hardware as well.

As Allen explained, the benefits of computer-based instruction are many and the obstacles to widespread adoption are not technological but economic and social. This point hearkens back to earlier discussion of strategies that are underused, as well as to a broader point that emerged throughout the workshop sessions: a broad, multifaceted approach offers the greatest potential to bring about meaningful improvements in driving safety for teens.