SBIR and the Phase III Challenge of Commercialization

Small businesses are a major driver of high-technology innovation and economic growth in the United States, generating significant employment, new markets, and high-growth industries.1 In this era of globalization, optimizing the ability of small businesses to develop and commercialize new products is essential for U.S. competitiveness and national security. Developing better incentives to spur innovative ideas, technologies, and products—and ultimately to bring them to market—is thus a central policy challenge.

Created in 1982 through the Small Business Innovation Development Act, the Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) program is the nation’s premier innovation partnership program. SBIR offers competition-based awards to stimulate technological innovation among small private-sector businesses while providing government agencies new, cost-effective, technical and scientific so-

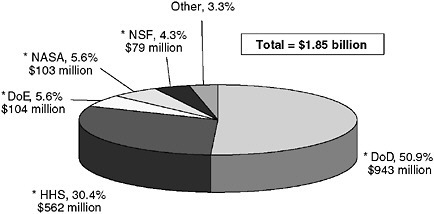

FIGURE 1 Dimensions of the SBIR program in 2005.

NOTE: These figures do not include STTR funds. * Indicates those departments and agencies reviewed by the National Research Council.

SOURCE: SBA, Retrieved July 25, 2006 from http://tech-net.sba.gov/.

lutions to meet their diverse mission needs. The program’s goals are four-fold: “(1) to stimulate technological innovation; (2) to use small business to meet federal research and development needs; (3) to foster and encourage participation by minority and disadvantaged persons in technological innovation; and (4) to increase private sector commercialization derived from Federal research and development.”2

SBIR legislation currently requires agencies with extramural R&D budgets in excess of $100 million to set aside 2.5 percent of their extramural R&D funds for SBIR. In 2005, the 11 federal agencies administering the SBIR program disbursed over $1.85 billion dollars in innovation awards. Five agencies administer over 96 percent of the program’s funds. They are the Department of Defense (DoD), the Department of Health and Human Services (particularly the National Institutes of Health [NIH]), the Department of Energy (DoE), the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), and the National Science Foundation (NSF). (See Figure 1.)

As noted, a principal goal of the SBIR program is for small businesses to commercialize their innovative product or service successfully. This commer-

cialization can include sales to the government through public procurement as well as sales through private commercial markets. In some cases, the technology can have dual uses, with the government gaining the benefit of an innovation, which later moves into the commercial market. In other cases, the initial award successfully meets the department’s goals, and no additional funds, or sales, are required.3

Commercializing SBIR-supported innovation is necessary if the nation is to capitalize on its SBIR investments. This transition is, however, challenging because it requires a small firm with an innovative idea to evolve quickly from a narrow focus on R&D to a much broader understanding of the complex systems and missions of federal agencies as well as the interrelated challenges of managing a larger business, developing sources of finance, and competing in the marketplace.

In cases where the federal government is the customer, small businesses must also learn to deal with a complex contracting system characterized by many arcane rules and procedures. Indeed, one major advantage of SBIR is that, to some extent, it permits small companies to sidestep some of the most impenetrable aspects of the procurement thicket that requires experienced experts in the federal acquisition regulations (FARs) to navigate and often works to the advantage of incumbents by providing the possibility of a sole source acquisition.4 This transition to commercial or agency use is supposed to take place in the final phase (Phase III) of the SBIR program. (See Box A.)

This challenge of transition—particularly for procurement by the Department of Defense and NASA of products funded by SBIR—was the subject of an NRC conference on June 14, 2005 as one element of its congressionally requested assessment of the SBIR program (see Preface). The focus of the NRC conference was the transition of technologies from the end of SBIR Phase II into acquisition programs at the Department of Defense and NASA.

This conference report captures the informed views of conference participants but not necessarily the consensus view of the committee. This introductory chapter provides the context of the SBIR commercialization challenge and highlights some of the key points raised at the conference. The next chapter provides a detailed summary of the proceedings of the conference.

|

Box A SBIR—A Program in Three Phases As conceived in the 1982 Act, the SBIR grant-making process is structured in three phases:

|

THE CHALLENGE OF TRANSITION AND PROCUREMENT

The challenge of technology commercialization includes the normal uncertainties of the development process common to all new technologies as well as unique institutional challenges found in federal procurement practices. Below, we first list some of the common challenges facing new firms that seek capital to develop and market their innovation. Following this, we address the specific challenges of firms that seek to commercialize their product through agency procurement.

Crossing the “Valley of Death”

Commercializing science-based innovations is inherently a high-risk endeavor.5 One source of risk is the lack of sufficient public information for potential

investors about technologies developed by small firms.6 A second related hurdle is the leakage of new knowledge that escapes the boundaries of firms and intellectual property protection. The creator of new knowledge can seldom fully capture the economic value of that knowledge for his or her own firm.7

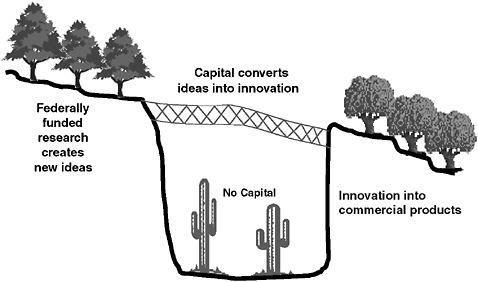

These challenges of incomplete and leaky information pose substantial obstacles for new firms seeking capital. The difficulty of attracting investors to support an imperfectly understood, as yet-to-be-developed innovation is especially daunting. Indeed, the term, “Valley of Death,” has come to describe this challenging transition when a developing technology is deemed promising, but too new to validate its commercial potential and thereby attract the capital necessary for its development.8 Lacking the capital to develop an idea sufficiently to attract investors, many promising ideas and firms perish. (See Figure 2.9) Despite these challenges, many firms attempt to make their way across this Valley of Death by seeking financing from wealthy individual investors (business “angels”) and, later in the development cycle, from venture capital firms.10

|

Technology Based Projects, Washington, D.C.: Department of Commerce/National Institute of Standards and Technology, 2000. |

|

6 |

Joshua Lerner, “Evaluating the Small Business Innovation Research Program: A Literature Review,” in National Research Council, The Small Business Innovation Research Program: An Assessment of the Department of Defense Fast Track Initiative, Charles W. Wessner, ed., Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press, 2000. For a seminal analysis on information asymmetries in markets and the importance of signaling, see Michael Spence, Market Signaling: Informational Transfer in Hiring and Related Processes, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1974. |

|

7 |

Edwin Mansfield, “How Fast Does New Industrial Technology Leak Out?” Journal of Industrial Economics, 34(2):217-224. |

|

8 |

As the September 24, 1998, Report to Congress by the House Committee on Science notes, “At the same time, the limited resources of the federal government, and thus the need for the government to focus on its irreplaceable role in funding basic research, has led to a widening gap between federally-funded basic research and industry-funded applied research and development. This gap, which has always existed but is becoming wider and deeper, has been referred to as the “Valley of Death.” A number of mechanisms are needed to help to span this Valley and should be considered.” See Committee on Science, Unlocking Our Future: Toward a New National Science Policy, A Report to Congress by the House Committee on Science, Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1998. Accessed at <http://www.access.gpo.gov/congress/house/science/cp105-b/science105b.pdf>. |

|

9 |

This diagram is adapted from Lewis Branscomb who in turn attributes it to a sketch made by Congressman Vernon Ehlers. See Lewis Branscomb and Philip Aurswald, Between Invention and Innovation: An Analysis of Funding for Early-Stage Technology Development, NIST GCR 02-841, Prepared for the Economic Assessment Office, Advanced Technology Program, Gaithersburg, MD: National Institute of Standards and Technology, November 2002. For a related policy reference to the Valley of Death, see Vernon J. Ehlers, Unlocking Our Future: Toward a New National Science Policy—A Report to Congress by the House Committee on Science, Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1998. Accessed at <http://www.access.gpo.gov/congress/house/science/cp105-b/science105b.pdf>. |

|

10 |

Jeff Sohl, “The Angel Market in 2004,” Center for Venture Research, University of New Hampshire. Accessed at <http://www.unh.edu/news/docs/cvr2004.pdf>. |

FIGURE 2 The Valley of Death

Angel investors are typically affluent individuals who provide capital for a business start-up, usually in exchange for equity. Increasingly, they organize themselves into angel networks or angel groups to share research and pool their own investment capital. The U.S. angel investment market accounted for over $22 billion in the United States in 2004.11 It is a source of start-up capital for many new firms. Yet, the angel market is dispersed and relatively unstructured, with wide variation in investor sophistication, few industry standards and tools, and limited data on performance.12 In addition, most angel investors are highly localized, preferring to invest in new companies that are within driving distance.13 This geographic concentration, lack of technological focus, and the privacy concerns of many angel investors, make angel capital difficult to obtain for many high-technology start-ups, particularly those seeking to provide goods and services to the federal government.

Unlike angels, venture capitalists, typically manage the pooled money of others in a professionally-managed fund. Within the last decade, the number of venture capital firms that invest primarily in small business tripled, and their

total investments rose eight-fold.14 This was followed by a sharp contraction in 2000 in the venture capital market, especially for new start-ups with low valuations. A contraction in the number of initial public offerings continues to concentrate fund managers’ attention on existing investments and selected “techbust” companies on the rebound.15 In 2005, venture capitalists in the United States invested $21.7 billion over the course of 2,939 deals. However, 82 percent of venture capital in the United States was directed to firms in the later stages of development, with the remaining 18 percent directed to seed and early stage firms. Together, these realities of the angel and venture markets underscore the challenge faced by new firms seeking private capital to develop and market even promising innovations.

The Challenge of Federal Procurement

Commercializing SBIR-funded technologies though federal procurement is no less challenging for innovative small companies. Finding private sources of funding to further develop even successful SBIR Phase II projects—those innovations that have demonstrated technical and commercial feasibility—is often difficult because the eventual “market” for products is unlikely to be large enough to attract private venture funding. As Mark Redding of Impact Technologies noted at the conference, venture capitalists tend to avoid funding firms focused on government contracts citing higher costs, regulatory burdens, and limited markets associated with government contracting.16

Institutional biases in federal procurement also hinder government funding needed to transition promising SBIR technologies. Procurement rules and practices often impose high costs and administrative overheads that favor established suppliers. In addition, many acquisition officers have traditionally viewed the SBIR program as a “tax’ on their R&D budgets, representing a “loss” of resources and control rather than an opportunity to develop rapid and lower cost solutions to complex procurement challenges. Even when they see the value of a technology, providing “extra” funding to exploit it in a timely manner can be a challenge that requires time, commitment, and, ultimately, the interest of those with budgetary authority for the programs or systems. Attracting such interest and support is not automatic and may often depend on personal relations and advocacy skills, not on the intrinsic quality of the SBIR project.

These acquisition hurdles and institutional bias towards SBIR remain a significant challenge for the program within DoD and NASA. Nevertheless, internal views of the SBIR program seem to be evolving in a positive fashion, although the impact of this evolution remains uneven. Some services, such as the

|

14 |

Jeffrey Sohl, <http://www.unh.edu/cvr/>. |

|

15 |

The Wall Street Journal, “The Venture Capital Yard Sale,” July 18, 2006, P. C1. |

|

16 |

See the presentation by Mark Redding, summarized in the Proceedings section of this volume. |

|

Box B Technology Insertion as a Team Effort A successful technology is the product of a complicated equation involving many different stakeholders in the acquisition community, the government S&T community and large and small businesses. “Each has a part to play, and it takes champions in each of those places to actually make it work.” Michael Caccuitto, SBIR Program Manager, Department of Defense |

Navy, have made substantial progress in changing their procurement culture so that SBIR is now seen to be a mechanism of considerable and, in some ways, unique usefulness to their acquisition officers.17 The need to bring the relevant stakeholders together to transition a technology requires advocates and close collaboration, as aptly described in Box B.

As we see next, this change in the perception of SBIR is becoming more widespread in the DoD acquisition process.18 In a major perceptual and political shift (that has taken place over the course of the Academies review,) prime contractors have begun to express much more interest in working with SBIR companies and are increasingly devoting management resources to capitalize on the opportunities offered by the SBIR awardees.19 This perceptual shift is important in that it validates the program in the acquisition process while opening opportunities for firms and program managers to transition the results of successful SBIR awards into systems and products to support the DoD mission.

SBIR PHASE III: ACTIVITIES AND OPPORTUNITIES

The Department of Defense and SBIR

Reflecting this evolution in the perception of the program, Dr. Charles Holland of the Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD) affirmed that SBIR is

|

17 |

See the summaries of presentations by Deputy Assistant Secretary Michael McGrath, Navy Program Executive Officer Richard McNamara, Navy Program Manager John Williams, and Richard Carroll of Innovative Defense Strategies in the Proceedings section of this volume. |

|

18 |

See Deputy Under Secretary of Defense (Industrial Policy), “Transforming the Defense Industrial Base: A Roadmap,” February 2003. This report highlights the importance of small businesses for building future war-fighting capacity. Accessed at <http://www.acq.osd.mil/ip/docs/transforming_the_defense_ind_base-full_report_with_appendices.pdf>. |

|

19 |

See the presentations by Boeing, Lockheed Martin, Raytheon, and ATK in Panel II of the Proceedings section of this volume. |

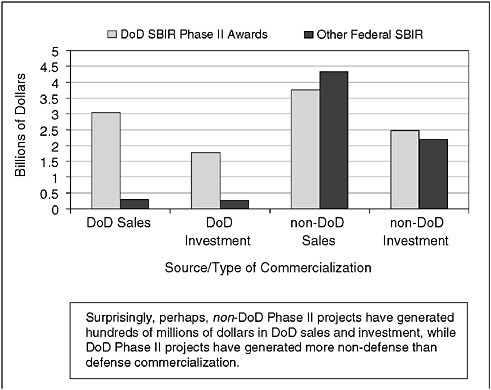

FIGURE 3 Phase III composition: Total sales and investment of DoD Phase II awards.

NOTE: Sixty-three percent of projects are DoD Phase IIs, and 37 percent are other federal Phase IIs, indicating a high degree of capture of non-DoD Phase II commercialization data.

SOURCE: Department of Defense CCR, 2005.

increasingly viewed as an important mechanism for helping to expand the nation’s science and technology base. He reported that while the commercialization of SBIR-developed products at DoD is split about equally between the private sector and acquisition by DoD and its prime contractors, the growth of Phase III contracts, reported through the department’s Central Contractor Registration, has outpaced the growth in the SBIR budget.

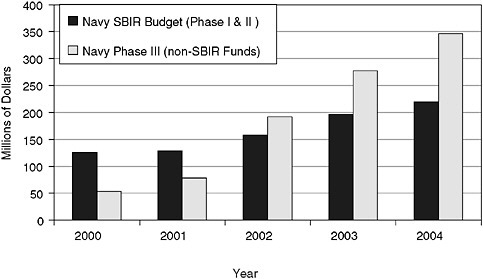

The full extent of these opportunities was also explained by Dr. Michael McGrath, Deputy Assistant Secretary of the Navy, who noted in his presentation that the Navy had had substantial success in expanding Phase III funding from $50M in 2000 to $350M in 2004. (See Figure 4.)

Dr. McGrath also underscored the utility of SBIR in offering the greater flexibility and shorter time horizon needed to move technologies more quickly into acquisition:

-

Flexibility. SBIR offers an unusual degree of execution year flexibility,

FIGURE 4 Navy Phase III success is growing.

NOTE: Phase III funding is from OSD DD 350 reports and may be under-reported. FY04 Navy Phase III ($346 million) comprises 114 separate contracts to 81 individual firms.

|

Box C SBIR’s Value to the Department of Defense The DoD’s SBIR Program Manger, Michael Caccuitto observed that the DoD SBIR program is designed to support two key DoD objectives: creating technology dominance, and building a stronger industrial base. Drawing on this observation, Dr. McGrath affirmed that for the Navy, SBIR is an “important source of innovation across the entire RTD&E (Research, Test, Development and Evaluation) spectrum.” |

-

unlike most accounts for research, testing, development, and evaluation that had to be described in detail in the President’s budgetary message. Dr. McGrath noted that, by contrast, the average cycle time from nominating a topic to awarding a Phase I in the Navy was 14 months.

-

Shorter Planning Horizon. SBIR allows for a much shorter planning horizon. Most R&D programs at DoD have to be planned years ahead of the budget cycle. SBIR does not. For example, Dr. McGrath cited the case of a 2005 initiative to address the threat posed by Improvised Explosive Devices in Iraq: A quick response topic generated 38 Phase I awards

-

within five months, 18 of which had already moved on to Phase II, with prototypes expected in the Iraq theater within six months.

Prime Contractors and SBIR

Representatives from the prime contractors indicated that SBIR Phase III collaborations are an increasing element in their corporate strategies and that these collaborations are based on growing recognition of their strategic value. These strategies include:

-

Diversifying the Supply Base. Several prime contractors noted that they are diversifying their supplier base to avoid single points of failure. This was one factor driving their interest in the SBIR program.

-

Improving Access to Expertise. For smaller prime contractors, SBIR also provides access to high-level expertise found within small innovative firms. As Earle Rudolph of ATK noted SBIR provides a route to new ideas and entrepreneurs able to develop them.

Richard Hendel noted that Boeing is expanding its SBIR-related activities from its Phantom Works to its Integrated Defense Systems and other large programs. Boeing has also submitted SBIR topics to agencies, some of which have been adopted. He added that DoD’s Multi-mission Maritime Aircraft and Future Combat Systems programs seemed especially interested in having Boeing submit topic suggestions.

Likewise, Raytheon’s John Waszczak stated that his company recognizes the value of small business collaboration. He noted that Raytheon’s Integrated Defense Systems, among other corporate divisions, have been working formally with SBIR for some years. He added that half to two-thirds of a typical program for Raytheon Missile Systems have been outsourced to subcontractors, and more than half of the companies involved meet the SBA definition of small companies.

|

Box D Some Successful SBIR Prime Contractor-Small Business Collaborations

|

Small Businesses and SBIR

Small business speakers also provided multiple examples of successful Phase III activities that met agency needs while providing their firms with new opportunities.

In an interesting case, the head of Advanced Ceramics Research (ACR), Anthony Mulligan, described the rapid growth of his company, adding that this growth also provided much-needed employment for Native Americans at the Tohono-O’odham Reservation near Tucson, Arizona. Founded in 1989 with $1000 and the hope of a Navy Phase II award, he pointed out that his company has grown to the point where its projected revenues for 2005 were $23.5 million, of which only $4 million were from SBIR. About one-third of the company’s government sales were transition dollars to get SBIR programs to commercialization. The company’s Silver Fox aerial vehicle is in use in Iraq and elsewhere, providing a low-cost platform for multiple tasks.20

Mr. Mulligan underscored that SBIR applications at ACR are driven by the company’s core strategic technology and business plan. He described his company as very disciplined in its use of the awards, noting that ACR had even turned down Phase I awards after its strategic plans had shifted away from that research topic.

The agencies, the prime contractors, and the SBIR recipient community all affirmed that with adequate Phase III funding, SBIR awards could lead to the development and delivery of important technologies that solve mission-driven problems for the agencies and the prime contractors while helping to support the growth of small high-technology businesses.

PHASE III CHALLENGES

Balancing the successes illustrated above, the conference also highlighted a wide range of concerns about Phase III from the perspectives of agency SBIR and acquisitions managers, award recipients, and prime contractors. Almost all speakers agreed that the absence of a dedicated funding source for Phase III

|

20 |

A result of research and development efforts with the Navy’s ONR SBIR program, the Silver Fox is a small, lightweight, inexpensive (and therefore expendable) unmanned aerial vehicle that is designed to fly autonomously for long durations at 60 knots and run on JP-5/JP-8 fuel. According to the Navy, “the Silver Fox was initially designed to spot whales in operating areas to keep them out of harm’s way before conducting naval exercises. However, in 2003 the Office of Naval Research and the ACR’s assembly of the Silver Fox resulted in the ability to provide operational systems to the Marine Corps who needed assistance with tactical reconnaissance missions in the Middle East. For the Marines, the Silver Fox employs high-tech “eyes” and relays information immediately to a remote laptop computer providing intelligence for advancing Marines. It has also been utilized in Operation Iraqi Freedom as an aerial chemical weapons detector.” Accessed at <http://www.dodsbir.net/SuccessStories/acr.htm>. |

|

Box E The Luna Innovation Model and SBIR The Luna Innovation Model was developed by Kent Murphy who founded Luna in rural southern Virginia. The Luna model uses multiple flexible funding instruments, both public and private, including SBIR, the Advanced Technology Program (ATP), venture capital, corporate partners, and internal funding to develop and commercialize ideas that were originally generated at universities or with commercial partners. Securing venture capital funding can be difficult even in the best of times; Luna received only two small investments during the late 1990s bubble. Also, as is noted above, venture capital firms tend to be highly specialized geographically, and Luna’s southern Virginia location has minimal local venture funding.a The path to technical and financial success is often complex for new technologies, especially those located in more rural areas distant from high-tech clusters. In one example, Luna Energies built its basic technology with funding from prime contractors and then used SBIR funding to develop applications for NASA and the Air Force. Eventually, it developed civilian applications for the energy industry, leading to its purchase by an energy company. According to Murphy, innovation awards from both SBIR and ATP were “critical” to Luna’s success.b |

represented a key challenge. Many of them had played a part in the development of successful Phase III projects and believed that there are important lessons to be learned about how SBIR can be more successfully structured to improve technology transfer.

Agency Concerns

-

Risk Aversion by Program Officers

Program officers and program executive officers control acquisition funds needed to move SBIR technologies eventually into weapons and other operational systems. As several conference speakers pointed out, however, Program managers and program executive officers often do not take an interest in SBIR. One reason is that while acquisition program officers are encouraged to reduce risk to the maximum extent possible, SBIR-based projects appeared to offer a number of added risks, both technical and personal, when compared to working through prime contractors.

As a result, program managers in charge of acquisitions have not traditionally seen SBIR as part of their mainstream activities. Mr. Nick Karangelen of

|

Box F DoD Risks Associated with SBIR Procurement from Small, Untested Firms Technical Risks. This includes the possibility that the technology would not in the end prove to be sufficiently robust for use in weapons systems and space missions. Company Risks. SBIR companies are by definition smaller and have fewer resources to draw on than prime contractors have. In addition, many SBIR companies had only a very limited track record, which limits program manager confidence that they would be able to deliver their product on time and within budget. Funding Limitations. The $750,000 maximum for Phase II might not be enough to fund a prototype sufficiently ready for acquisition, necessitating other funds and more time. Testing Challenges. SBIR companies are often unfamiliar with the very high level of testing and engineering specifications (mil specs) necessary to meet DoD acquisition requirements. Scale Issues. Small companies may not have the experience and resources necessary to scale production effectively to amounts needed by DoD. Timing Risks. DoD planning, programming, and budgets work in a two-year cycle, and it is difficult for program executive officers to determine whether a small firm will be able to create a product to meet program needs in a timely manner, even if the initial research has proven successful. |

Trident Systems observed more specifically that the 100 largest contracting companies currently perform 89.9 percent of all defense R&D. Less than four percent went to small businesses. Only about 0.4 percent of all R&D generated by the government went to small technology businesses, even though one-third of all U.S. scientists and engineers were employed there.

Risk aversion is by no means peculiar to DoD. Moreover, it is entirely understandable in programs and equipment where lives could ultimately be at stake. At NASA as well, program officers usually have only one opportunity to get their projects right, given limited opportunities for in-flight adjustments. Recognizing this constraint, NASA’s Carl Ray noted that many of NASA’s program managers still need to be convinced that SBIR can deliver reliable technology on time and at a manageable level of risk.

-

The Management Challenge: Viewing SBIR as a “tax” rather than an opportunity

As noted earlier, attitudinal issues also affect the Phase III transition, creating institutional biases in procurement that pose an extra hurdle for small firms seeking to commercialize SBIR-based products. Several speakers observed that some program managers in the acquisition offices have viewed SBIR as “more

as a tax than as an opportunity” to identify and support new technologies. To them, the 2.5 percent of the agency’s extramural R&D budget that is set aside for SBIR represents a loss of resources and control rather than an opportunity to develop rapid and low-cost solutions to complex procurement challenges. Illustrating this point, the Navy’s McGrath noted that SBIR funds at Navy over-whelmingly came from its advanced development, testing, and evaluation functions (often referred to in the DoD idiom as 6.4-6.7 functions) but were spent on basic applied research and technology development (or 6.1-6.3 functions.) This has led to perceptions among managers involved in advanced development, testing, and evaluation that SBIR is simply a tax on their programs. This perception, in turn, can lead to limited managerial attention, less optimal mission alignment, and few resources being devoted to the program.

-

Administrative Funding Constraints

The fact that the SBIR legislation does not permit the agencies to use SBIR funds for administration of the program is seen as another constraint. The Air Force’s Major Stephen stated that four staff members at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base administer the entire Air Force SBIR program, and that while the program had experienced 70 percent growth over the previous five years, there had been no additional funding for transition assistance or program administration. In his view, the result is that the Air Force has no funds to track or document success. In turn, this made it harder to demonstrate the value of the program to acquisition program managers.

-

A Need for Gap Funding

SBIR funding normally ends with Phase II, corresponding typically with Technology Readiness Levels (TRL) of 3-5. The SBIR program does not allow SBIR funding for further work beyond Phase II to ready the technology for use. Other acquisition funding is needed to develop the technology further. However, acquisition programs are often not prepared to fund this work given the high level of risk involved in technology development.

In Lockheed’s view, the key to the TRL transition from TRL 4-5 to TRL 7-8 is the presence of available funding on hand. This reflected the comments of many speakers that smoothing the funding path across the route from TRL 4-5 to TRL 7-9 would remove a major barrier blocking improved take-up of SBIR projects into acquisition programs.

According to Mark Redding of Impact Technologies, venture capitalists were unwilling to step into the gap partly because government contracts might not be large enough to ensure the necessary level of commercial viability, and partly because the longer time horizons and significant uncertainty involved in govern-

ment contacting did not fit with the relatively short time horizon and market focus of venture capital firms.

Phase III is supposed to address this gap, but many speakers noted that it had not done so very effectively. Most of the speakers discussed in some fashion the absence of dedicated funding for Phase III—in contrast to Phase II—which meant that Phase III had to be considered quite differently.

-

Cycle Time Mismatches

In some cases, SBIR projects could be completed too soon for entry into acquisition programs that anticipate funding purchases some years out in the future. On the other hand, SBIR projects cannot be budgeted far in advance—far enough to be part of the planned acquisition program—because it was unclear whether they would be successful. These cycle time mismatches are a source of uncertainty for the program.

-

Linkages among Agencies, Prime Contractors, and Small Businesses

Several speakers, including Kevin Wheeler of the Senate Small Business and Entrepreneurship Committee staff, noted that communication was not always good as it might be among the agencies, the prime contractors, and the small business research community. Prime contractors often have difficulty identifying the technology assets of small businesses; small businesses often had weak links to the prime contractors. The Boeing representative supported this perception, noting that the company was eager to partner with small businesses and had a significant track record with the SBIR program, but that small businesses rarely came to Boeing seeking partnerships.

-

Improving Topic Generation

A number of speakers—including OSD’s Dr. Holland and Mr. Caccuitto— said that there had been substantial improvement in the links between acquisition interests and topics, and that 60 percent or more of topics were now either sponsored or endorsed by program managers or program executive officers. In the Navy, acquisition offices supported or endorsed more than 80 percent.

However, the Air Force’s Major Stephen observed that improved topic generation—i.e., development of topics more relevant to program executive officers—would also tend to reduce the timeliness of topics. Overall, the Air Force in particular believed that reducing cycle time for topic generation should be a top priority for the program.

While several speakers mentioned the need for closer links between topics and acquisition offices, John Parmentola of the Army also observed that it was

necessary to balance rapid commercialization against long-term research needs. In fact, the Army needed both.

Small Businesses’ Concerns

While much of the conference focused on the ways in which government agencies and prime contractors could adjust their activities to generate more effective linkages from Phase II to Phase III, several speakers observed that small businesses too could make adjustments to improve the success of Phases I, II, and III.

ACR’s Anthony Mulligan said that hard work and desire were not always enough for success. He noted that there are real barriers for small businesses to overcome in linking with an acquisition program, noting that there is “no effective bridge between the acquisition community and those who are developing innovative technologies.”

Many speakers supported the view that the Valley of Death between development and acquisition was a real and substantial problem for small businesses. A number of related concerns emerged:

-

Timing. Small businesses are often disadvantaged by the very slow pace of acquisition.

-

Complexity. The acquisition process is both complex and unique, and small firms face a steep learning curve and high overhead costs.

-

Venture Funding. As noted, few small firms have the staff or resources to do the market analysis necessary to attract funding from venture capital firms that, in many cases, tend not to be highly motivated to invest in firms involved in government contracting.

-

Small Amount of Additional Funding. Impact Technologies’ Mark Redding noted that his company had successfully won more than 30 Phase III awards—but that these had averaged only $50,000 each.

-

Planning. A number of agency staff noted that companies needed to be concerned with commercialization, and planning their Phase III activities, right from the start—even during Phase Zero before the first Phase I was awarded.

-

Roadmap Inclusion. Much technical planning in acquisition is driven by roadmaps developed by program officers and prime contractors. Failure to integrate SBIR and small businesses generally into the roadmaps means that they are likely to be excluded from acquisition programs, regardless of the success of SBIR projects.

-

Contract Downsizing. Even once a substantial Phase III has been awarded, there are no guarantees that the budget will be maintained at the contracted level. For example, Orbitec’s $57 million NASA Phase III

-

was reduced by more than 80 percent after the first year. Such decisions can dramatically affect the transition of SBIR-funded technology.

-

Budget Squeeze. Orbitec survived only because of successful lobbying of allies in Congress and at NASA. In general, small businesses often lack the influence to maintain budget levels when agencies change priorities—and this can be devastating for companies with few other resources to devote to a promising technology.

-

More Partnering. A number of speakers urged small businesses to team with prime contractors rather than seek government Phase III business on their own.

Prime Contractors’ Concerns

The prime contractors present at the conference also identified a number of concerns including:

-

Lack of Efficient Links to Small Firms. Many speakers cited the example of the Navy Opportunity Forum as a means of making connections among agency program officers, SBIR program officers, prime contractors, and small businesses, as well as venture capitalists and other sources of funds.. However, the Forum was described as a unique phenomenon because other agencies do not make available the funds and management attention needed for similar activities.

-

Lack of Systemic Focus. SBIR projects tend to focus on technical problems, not systematic needs

-

Inadequate SBIR Database for Awards and Solicitations. Prime contractors and small firms would benefit from better capabilities for matching up prime contractor technology needs with the capacities of small firms.

-

Cultural Differences. Differences in social and work cultures can make small businesses hesitant to work with prime contractors.

-

Lack of Evidence and Cases. There is a need for documentation that demonstrates real positive returns on investment for the prime contractors for involving small businesses in their technology development programs.

-

Intellectual Property Concerns. Agencies need to understand and address small business concerns about intellectual property and protect their intellectual property even under pressure to move a product forward. University partnerships are also a source of intellectual property concern for some businesses.

AGENCY INITIATIVES AND RECENT DEVELOPMENTS

In recent years, several of the DoD agencies have sought to address the issues raised above, through a variety of policy and program initiatives. Agency representatives described the initiatives undertaken in their agencies to meet these needs. These included:

-

Sponsorship of Topics. Acquisition offices currently sponsor or endorse more than half of all DoD topics. At Navy, the acquisition-driven model of topic development had been expanded further, according to Dr. McGrath. He noted that 84 percent of Navy topics came from the acquisition community and that Program Executive Officers in the Navy’s Systems Commands participated in selecting proposals and managing them through Phase I and Phase II.

-

Direct Program Executive Officer Sponsorship Pilot. A 2005 Army pilot program to allocate 10 topics to program executive officers also had the additional effect of driving SBIR toward applied research. This constitutes a shift away from the traditional Army Research Office focus on more basic research.

-

The Navy “Primes Initiative.” Begun in 2002, the Navy Primes Initiative is an effort to connect prime contractors to the SBIR program in a more formal way. As noted, prime contractors have become increasingly interested in more access to the SBIR program.

-

Fast Track Initiative. Started in 1995, this initiative is aimed at speeding up Phase II awards for companies that could demonstrate matching funds.21

-

Extra large Awards. Larger awards (beyond $750,000) are sometimes used, partly as a way of “exciting the interest of program officers,” according to Major Stephen.

-

The Transition Assistance Program (TAP). The Navy’s TAP provides mentoring and a management assistance program for supporting commercialization (i.e., transition) through the Phase III maturation process.22

|

21 |

In an earlier assessment of the Fast Track program, the NRC noted that “the case studies, surveys, and empirical research suggest that the Fast Track initiative is meeting its goals of encouraging commercialization and attracting new firms to the program.” See National Research Council, The Small Business Innovation Research Program: An Assessment of the Department of Defense Fast Track Initiative, Charles W. Wessner, ed., Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press, 2000. |

|

22 |

According to the Navy, the goals of the Transition Assistance Program are to facilitate DoD use of Navy-funded SBIR technology and to assist SBIR-funded firms to speed up the rate of technology transition by developing relationships with prime contractors, as well as other activities aimed at preparing the SBIR firm to deliver product. TAP is a competitive 10-month program offered exclusively to SBIR and STTR Phase II award recipients. Information accessed at <http://www.dawnbreaker.com/navytap/>. |

-

Training and Education. The Air Force has implemented a training and education program for prime contractors and program offices.

-

Better Tracking. Improved outcomes tracking through the Commercialization Achievement Index (CAI) was established in 2000 to measure the commercial track record of proposing firms.

-

Outreach. As noted, the Navy Opportunity Forum brings together SBIR firms, prime contractors, and program executive officer and program managers, offering important networking opportunities and is well received by participants.

-

New Funding Initiatives. These include OnPoint, the Army’s venture capital initiative (soon to be paralleled by NASA’s Red Planet) to help technology transitions and earn a return on investment. OnPoint invests in small entrepreneurial companies including those that would otherwise not be doing business with the Army.

-

Roadmaps. These are initiatives focused on developing joint technology maps and coordinated planning processes. They include:

-

Navy Advanced Technology Review Board process for evaluating across programs

-

Joint Strike Fighter Technology Advisory Board, which reviews program priorities and includes the program office, contractor team, and S&T organizations of every service partner

-

-

High-quality Reviewers. Peter Hughes of NASA noted that high-quality reviews, needed to select high-quality projects, are important for the credibility of the SBIR program and for the capacity. He noted that NASA is upgrading this area of its program.

Other Recent Developments

Complementing these agency efforts, the prime contractors also noted that they are making significant efforts recently to increase their levels of involvement in SBIR. Boeing’s Richard Hendel noted, for example, that his company now has a full-time SBIR liaison, up from a previous allocation of 25 percent. Some small businesses are also now more committed to working with prime contractors, with several noting the importance of the Navy’s programs in this connection.

Small businesses are also adopting a wider portfolio of strategies to improve commercialization results. For example, ACR’s Anthony Mulligan noted that while his company had originally sought closer connections with program officers, it was now “reaching out to the war fighter.” Once the advantages of a technology or product could be demonstrated to those charged with its use, their interest could help the company to “push the middle”—the program managers and program executive officers—to move forward with Phase III financing.

PARTICIPANTS’ SUGGESTIONS FOR IMPROVING PHASE III

Some speakers focused on possible changes in agency program management, including better use of incentives for managers, roadmaps, and greater matchmaking. Others focused on ways in which small businesses and the prime contractors could better align their work to improve Phase III outcomes.

|

Box G A Caveat Regarding the Issues Noted Below This report summarizes the issues raised over the course of an NRC conference on SBIR commercialization challenge. By capturing the perspectives of agency officials, prime contractors, and small business leaders, the conference has helped to inform the deliberations of the NRC committee that is reviewing the SBIR program. The views of these participants are valuable because they reflect in many cases tacit knowledge that has been gained through operational experience with the program. By recording their observations, this report captures new information concerning managerial, performance, and cultural issues and perspectives that the SBIR program must address to realize its full potential. The inclusion of these perspectives should not be seen necessarily as an endorsement of the views of participants; they do represent informed views on potential modifications and additions to the SBIR program. |

Incentives for Better Program Management

Acquisition officers play a key role in moving SBIR to Phase III. They control funding allocations, making their involvement and acceptance of SBIR critical for successful technology transition. However, as several speakers noted, program executive officers and program managers often face a range of requirements including schedule and cost constraints that could be disrupted by the failure of an unproven technology. As a result, program executive officers are often understandably risk averse, wary of new unproven technology programs, including those from SBIR.

To overcome this risk aversion, appropriate incentives have to be introduced to make SBIR technologies more viable. The Navy’s McGrath noted that, with appropriate incentives, program executive officers can overcome the risks that limit their use of SBIR-funded technologies. Some of the incentives described at the conference include:

-

Alignment. Entering the SBIR company into a program with which the program executive officer was already engaged is one way to better focus SBIR projects on outcomes that directly support agency programs (and program officer) objectives. As noted by some speakers, this could allow SBIR projects to connect with Phase III activities already under way.

-

Reliability. This involves identifying technologies that have been operationally tested and need little if any modification. This suggestion by a participant reflected widely held views that program executive officer involvement was critical in bringing SBIR technologies to the necessary readiness level.

-

Capacity. As Dr. McGrath noted, SBIR firms need to take steps to convince program executive officers not only that the SBIR technology works, but also that the small business will be able to produce it to scale and on time.

-

Budget Integration. Some participants noted that program executive officers needed to see that the SBIR set-aside will be used to further their own missions. This calls for building SBIR research into the work and budget of program offices. By contrast, the Air Force’s program offices submit a budget based on independent cost estimates. SBIR awards are then taken as a 2.5 percent tax out of that budget.

-

Training. Major Stephen noted that training program executive officers to help them understand how SBIR can be leveraged to realize their mission goals is necessary. However, Mr. Carroll of Innovative Defense Strategies noted that SBIR training had been part of the general program executive officer training curriculum for one year, but had since been deleted.

-

Partnering. As described by Carl Ray, the SBIR program at NASA is forming partnerships with mission directorates aimed at enhancing “spin-in” —the take-up of SBIR technologies by NASA programs.

-

Emphasizing Opportunity. Dr. McGrath noted that the Navy’s SBIR management attempts to provide a consistent message to program executive officers and program managers—that “SBIR provides money and opportunity to fill R&D gaps in the program. Apply that money and innovation to your most urgent needs.”

Roadmap Integration

The integration of subprojects, such as those funded by SBIR, into larger operational systems is a complex and long-cycle process. For this reason, some participants emphasized the need to coordinate small business activities with prime contractor project roadmaps. Lockheed’s Mr. Ramirez noted that “to make successful transitions to Phase III, SBIR technologies must be integrated into an overall roadmap.” Lockheed Martin uses a variety of roadmaps to that end, including both technical capability roadmaps and corporate technology roadmaps.

The Raytheon representative added that roadmaps are important because it is necessary to coordinate the technology transition process across the customer, the supply chain, and small businesses. Coordination should include advanced technology demonstrations, which could be used to integrate multiple technolo-

gies into a complex weapons system. Raytheon’s Waszczak reported that his company designates a lead executive to develop a roadmap in cooperation with DoD program managers. The roadmap then allows program officers to “generate effective pull,” via the leads to the prime and to smaller subcontractors.

Lockheed’s Ramirez also suggested that, in the end, improvement in Phase III outcomes would require the development of a more strategic and longer-term outlook among all the participants. Better strategic vision would also allow improved alignment between programs, prime contractors, and small businesses.

Several speakers also noted that planning activities should start very early in the technology development cycle, if possible during “Phase Zero”—the stage at which topics were being developed.

Outreach and Matchmaking

Commentary at the conference also focused on the need for more events like the Navy Opportunity Forum that foster better communication as well as on the need to improve databases that share technology results across agencies. Several prime contractor representatives supported this approach. Lockheed’s Ramirez, for example, noted that his company was committed to reach out more to the small business community via the Navy Opportunity Forum and other mechanisms. Raytheon’s Waszczak noted that SBIR is now considered an extension of the company’s R&D program, but he also noted that effective use of the program required establishing long-term relationships with key small businesses, and good coordination between acquisition managers, small business, and the prime contractors. Mr. Waszczak added that while Raytheon saw Phase II as the prime contractor’s key entry point into the SBIR program, the prime contractors also need to be aware of the project at the development stage.

Specific suggestions for improving these linkages included:

-

Tracking. Mr. Karangelen said that project tracking was insufficient. Senior agency executives were required to track SBIR projects that were part of their plans and budget as technology development continued. However, except for a few officers especially in the Navy, tracking was insufficient.

-

Improved Liaison between Acquisition and SBIR Programs. Mr. Karangelen noted that the FY1999 defense authorization act mandated designation of liaison officers by the major acquisition programs for the SBIR community, a few individuals now represented dozens of programs. He believed that a designated liaison was needed for every program.

-

More Funding for Outreach. A number of speakers commended the Navy’s Transition Assistance Program, and several suggested that funding for similar efforts be expanded.

|

Box H Attributes of the Navy’s SUB program The SUB Program Executive Office is widely considered to be one of the more successful Phase III programs at DoD. The program takes a number of steps to use and support SBIR as an integral part of the technology development process. Acquisition Involvement. SBIR opportunities are advertised through a program of “active advocacy.” Program managers compete to write topics to solve their problems. Topic Vetting. Program executive officers keep track of all topics. Program managers compete in rigorous process of topic selection. SBIR contracts are considered a reward not a burden Treating SBIR as a Program, (including follow-up and monitoring of small businesses and how to keep them alive until a customer appears). Program managers are encouraged to demonstrate commitment to a technology by paying half of the cost of a Phase II option. Providing Acquisition Coverage, which links all SBIR awards to the agency’s acquisition program. Awarding Phase III Contracts, within the $75 M ceiling that avoids triggering complex Pentagon acquisition rules. Brokering Connections between SBIR and the prime contractors. Recycling unused Phase I awards, a rich source for problem solutions. |

Other Possible Agency Initiatives and Strategies

-

Small Phase III Awards. Mr. Crabb noted that these could be a key to bridging the Valley of Death. NASA for example sometimes provided a small Phase III award—perhaps enough money to fly a demonstration payload—for a technology not ready for a full Phase III.

-

Larger Phase II Awards. Some speakers thought that larger awards would make it easier for small firms to cross the Valley of Death.

-

Unbundling Larger Phase III Awards. One example cited at the conference was the unbundling in 1995 of a large contract to Lockheed and McDonnell Douglas for a complex life sciences module that led to Orbitec’s $57 million Phase III award.

-

Redefining SBIR and Testing and Evaluation. Some participants suggested that DoD and SBA adopt a wider view of Research, Testing, Development and Evaluation (RDT&E), so that SBIR projects could qualify for limited testing and evaluation funding. That in turn would help fund improvements in readiness level.

-

Databases. Some speakers observed that better technology matching capabilities would be very helpful. Suggestions included development of a frequently updated technology and report database with common organizational standards across all agencies.

-

SBIR and the Critical Path. Mr. Hughes noted that NASA was at pains to ensure that SBIR projects were not on the critical path until risk mitigation strategies were completely in place.

-

Spring-loading Phase III. Put in place milestones that would trigger initial Phase III funding.

Aligning Small Business Strategy

A number of speakers suggested that it was critical for small businesses to get their own strategies right in approaching SBIR with a view to moving on to Phase III. While the number of Phase III awards might be small, small businesses did have options that would enhance their chances of reaching Phase III, which was, as several speakers observed, where the real pay-off for small businesses occurred.

ACR’s Mulligan noted that SBIR should be tightly connected to the company’s overall strategy. His company consistently rejected SBIR topic opportunities that did not meet strategic needs, and had in at least one case returned a Phase I award that no longer fit with a changed strategic plan for the company.

Speakers also noted that it was critical for small businesses to focus on gaps identified via technology roadmaps—which represented real opportunities for Phase III—and in particular on finding ways to participate in the development of roadmaps and the identification of gaps.

Impact Technologies’ Redding noted that it was possible to increase the success rate of SBIR applications, which his company had done by successfully teaming with universities and prime contractors on Phase I applications (where the latter were subcontractors), and also by ensuring that customer requirements for Phase III were part of the company’s strategic approach from Phase I.

Understanding customer requirements should be part of the entire project. As the Air Force’s Major Van Zuiden pointed out, companies hoping to work on the Joint Strike Fighter should realize that “weight is king,” and that any proposal that was heavier than an existing technology would not fly.

Prime Contractors

Speakers from the prime contractors suggested that recent increased attention to SBIR could help improve the program in several ways, including more incentives for prime contractors to work with small business. These improvements might include:

-

More funding specifically for Phase III funding, although some speakers were careful to point out that this funding should not come from the existing Phase I and Phase II funding.

-

Assurance that there are realistic agency plans for Phase III.

-

Better understanding among the prime contractors that existing agency requirements to work with small and disadvantaged business can be met through SBIR.

-

Greater appreciation of the sole-source contracting advantages that accrue to extensions of successful SBIR awards.

SUMMARY

The views of the program managers, representatives of the prime contractors, program executive officers, and small company executives captured in this conference, and summarized in the next part of this report, reveal a growing and widely based recognition that the SBIR program can play a key role in providing timely and innovative technology solutions to agency missions.

The conference served to highlight a number of common elements, some of them relatively new developments in the perception and operation of the SBIR program. For example, the meeting revealed that the leadership at the Department of Defense, prime contractors, as well as small innovative businesses see SBIR as an increasingly important tool that aligns operational incentives with broader mission goals. Senior representatives of the Department affirmed the program’s role in developing innovative solutions for mission needs. Further underscoring the program’s relevance, prime contractors represented at the conference stated that they have focused management attention, shifted resources, and assigned responsibilities within their own management structures to capitalize on the creativity of SBIR firms.

The meeting also highlighted how Office of Naval Research and various branches of the Navy, especially the Navy Subs Program Executive Office, have successfully leveraged the SBIR program to advance mission needs. Their experience demonstrates that senior operational support and additional funding for program management provides legitimacy and the means needed for the program to work more effectively. In addition to funding program operations, this additional support allows for the outreach and networking initiatives (such as though the Navy Forum) among other management innovations that contribute to enhanced matchmaking, commercialization, and to the higher insertion rates for the Navy SBIR program.

In short, the experience of the Navy demonstrates that the SBIR works when each of these participants recognizes program benefits and is willing to take part in facilitating the program’s operations. With the right incentives and management attention, the performance and contributions of the SBIR program might be improved. What is interesting is that each of the main actors in the DoD/NASA innovation process is increasingly finding the SBIR program to be directly relevant to their interests and objectives.

To capitalize on SBIR’s potential, both better information (for small companies and large prime contractors) and supportive incentives are necessary. At the

|

“Program managers need incentives to work with small business. Program managers in the federal acquisition community do not intentionally shun the small business community, but they have no strong incentive to embrace a new technology or process from a small business when the risk is likely to be higher.” Anthony Mulligan, Advanced Ceramics Research |

NRC conference, representatives from the agencies, small businesses, as well as the prime contractors identified additional awards, closer involvement of primes in topic selection, and better follow-on Phase III funding, and integration of SBIR companies in roadmaps and other planning devices as important to successful SBIR technology transitions.

This growing recognition of the value and potential of SBIR is now changing attitudes towards the program within the acquisition community. Program managers and executives across DoD seem to be seeing the program’s potential as an integral part of the development and acquisition process. SBIR is seen less as a “tax” and more as a versatile tool to rapidly transition innovative technologies that address current mission needs.

This is a welcome development since the potential of the SBIR program to support agency missions fundamentally depends on how well it is used. A major purpose of the NRC study of SBIR is to develop and share a wider understanding of this program’s achievements and challenges so that its potential may be more fully realized. The suggestions made by the participants in this conference may well contribute to this objective.

Some initial progress on new policy has already occurred. As this volume goes to press, the conference it reports on has already served to bring the issue of Phase III commercialization to the attention of Congress and Executive Branch policymakers.23