Panel II

New National Models

Moderators:

Bradley Knox

House Committee on Small Business

and

Charles W. Wessner

National Research Council

Briefly introducing the speakers for the day’s second panel, Stefan Kuhlmann, Heikki Kotilainen, and Peter Nicholson, Mr. Knox thanked all three for traveling considerable distances and said those in attendance were anticipating their contributions with interest and excitement. He called on Dr. Kuhlman to present first.

THE RECORD AND THE CHALLENGE IN GERMANY

Stefan Kuhlmann

Fraunhofer ISI, Germany

Dr. Kuhlmann expressed gratitude at being offered a chance to participate in what he characterized as an interesting and challenging event being held in an environment that was impressive both institutionally and architecturally. He said that he had been asked to speak about the status of research in Germany and the country’s research innovation system, whose development is increasingly becoming part of a European research system.

Dr. Kuhlmann then outlined a presentation that was structured in four parts. Part one laid out the strengths and weaknesses of the German innovation system. Part two briefly introduced the governance structure of innovative research in Germany and the related institutional landscape. Part three delved into innovation policy and programs, at both the level of the German federal government and the level of the Länder, which in the German context was the equivalent of the U.S. state level. Part four considered a number of current developments and challenges for the future.

Strengths of Germany’s Innovation System

Germany’s strength is that it has been and continues to be highly “innovation oriented.” Its gross R&D expenditures have been running at just under 55 billion euros, or around 2.5 percent of GDP. Quite strong in the 1980s, the country’s spending on R&D had fallen during the early 1990s in conjunction with reunification but has been increasing in recent years. Companies account for 66 percent of R&D expenditure, a considerable share in Dr. Kuhlmann’s view, and Germany leads the European Union (EU) in the percentage of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) innovating in-house. Germany’s 14.9 percent of the world market for R&D-intensive goods places it second behind the United States, and it is in the EU’s top three in share of manufacturing sales attributed to new products. Its number of patent applications per inhabitant, 127, is second-highest among large countries, and it ranks third among all nations in international publications with 9 percent of the total.

Dr. Kuhlmann noted that in 2001, business provided the largest share of R&D financing by far, followed by the federal and Länder governments. A small amount of R&D expenditure came from abroad, from either the European Commission or private-sector sources, which had been funding R&D to be performed in Germany with growing frequency. Business dominated performance of R&D as well, followed by the higher-education sector and by nonuniversity research institutions, the latter being a feature typical of the German system and one that he promised to return to later in his talk.

Germany’s Weaknesses

Calling the persistence of risk-averse behavior among banks one of the major weaknesses of the German research system, Dr. Kuhlman noted that financing innovation has become increasingly difficult, especially for SMEs. He then listed some of Germany’s other weaknesses:

-

It is suffering a clear loss of momentum in some, although not all, of the high-tech sectors in which it had been strong—among them, pharmaceuticals, computers, electronics, and aircraft.

-

Its technological performance has come to depend increasingly on the automotive sector.

-

East Germany and Berlin together eat up nearly one-quarter of the 9 billion euro federal research budget while employing only 11 percent of the country’s R&D personnel and accounting for only 6 percent of its patent production. Yet, East Germany is “not very strong in competitive and innovation terms” despite the amount of money invested there.

-

The performance of Germany’s educational system, long considered quite strong, has declined to the point that Dr. Kuhlmann talked of a “crisis” and envisaged an expensive restructuring.

-

The growth of the public sector’s R&D spending is lagging that of the private sector over two decades ending in 2001. More recent data would show a slight increase in public and some stagnation in business R&D investment, he noted.

Governance Structure of the German Innovation System

Turning to the complex governance structure of Germany’s system of innovative research, Dr. Kuhlmann listed three levels in descending order—Federal (National), Länder (State), and Regional (substate groupings)—that he said were overarched by an “increasingly relevant” Supranational level, represented specifically by the European Union.

Existing on the national level in Germany, exemplifying a phenomenon found in many European countries, is “a kind of competition” between the Federal Ministry of Research and Education and the Federal Ministry of Economics and Labor. Although there is collaboration within the government, there is some duplication as well, and it is not clear who was in charge of research, technological development, and innovation. At the state level, interstate competition mirroring that found in the United States is on the rise. Relations between the federal government and the Länder are marked by “coopetition,” with initiatives at the two levels sometimes in conflict, sometimes complementary. The regional level depends on the federal and state levels for investment.

While governance at the European level is gaining in importance, the role of EU investments is of greater relative significance in the smaller nations among the EU-25. Germany, Dr. Kuhlmann estimated, receives some 5 percent of the R&D funding that comes through EU channels. Still, there are exceptions according to sector: In information and communications technology (ICT) in Germany, where national programs had not been very strong, EU funding has played a more important role than in other areas. Despite much discussion of “subsidiarity”—as complementarity among initiatives at the EU, national, and state or Länder levels was called in official EU parlance—there is, in practice, a great deal of both overlap and confusion.

The Institutional Landscape of German Research

Dr. Kuhlmann noted that the German research system’s institutional landscape varies from basic to applied research, with funding sources spanning from public to private organizations. While industry, which contributes the lion’s share of the country’s R&D investment, is mainly occupied with applied research, it also participates in some areas of fundamental research. Universities receive state and federal funding, though they increasingly receive money from industry and conducted applied as well as basic research. The 8 billion euros received by universities covers research as well as teaching.

Dr. Kuhlmann then focused specifically on the nonuniversity research institutions: the Max Planck Society (MPG), which does excellent basic research; the Helmholz-Gemeinschaft (HGF), a national organization with 15 major centers doing research in many fields and particularly in “problem-driven” areas; and his own organization, the Fraunhofer Gesellschaft (FhG), which does applied research on a contract basis and receives a small amount of institutional funding. Problems beset collaboration among the actors occupying the contract-research area, he said. But collaboration with industry is “quite well developed” and, as such, no longer the issue it was in the 1980s and 1990s.

He next turned to the basic mechanisms of federal R&D funding in Germany. The leading category, at nearly 47 percent of the total, is “institutional funding,” which goes to such nonuniversity research organizations as Max Planck, Helmholz, and Fraunhofer. Project funding, routed through programs at the federal level, represents 40 percent; its share, greater in the 1980s, decreased through the 1990s as institutional funding rose. The role of project and program funding in innovation policy is thus exhibiting some shrinkage in Germany, although not to the point that it has lost its relevance.

Innovation Policy Programs: BMBF

The two main providers of funds at the national level, as mentioned above, are the Federal Ministry of Education and Research, or BMBF (Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung), and the Federal Ministry of Economics and Labor, or BMWA (Bundesministerium für Wirtschaft und Arbeit). The BMBF supports a broad variety of technology and innovation programs—so broad, in fact, as to be difficult to track.

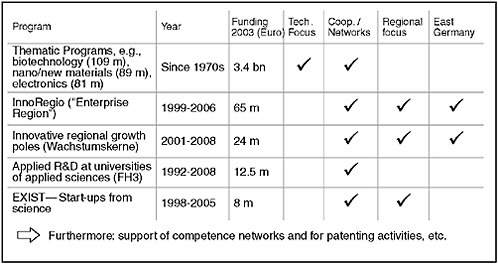

For this reason, said Dr. Kuhlmann, presenting a full list of these thematic programs is infeasible. Although there are official lists, none of these lists reflects a precise technology or innovation program. He and coworkers therefore assembled a table (Figure 8), that encompasses 3.4 billion euros’ worth of programs. These range from biotechnology and nanotechnology programs to initiatives on new materials and electronics. Some fund technological research, but many contain an element of innovation support. This element, when present, owes its

FIGURE 8 Innovation policy programs, federal level: BMBF (selection).

SOURCE: Adapted from Federal Budget BMBF 2003, BMBF 2004.

existence in large part to the programs’ having been conceptualized as cooperative; that is, as a basic precondition for getting them funded, they have to include some degree of collaboration between researchers from the public sector, including academia, and industry.

The table’s remaining categories are likewise incomplete, Dr. Kuhlmann said, and for similar reasons. Among them was the InnoRegio program, which is aimed at networking in regions of eastern Germany. Also listed were: “Innovative Regional Growth Poles,” a program similar to InnoRegio; support for research in the Fachhochschulen (FH3), or universities of applied sciences; and EXIST, which helps universities develop a startup-friendly climate. He pointed out that a significant feature of this admittedly incomplete table is that funding for the four programs aimed specifically at innovation is small compared to funding for the thematic programs.

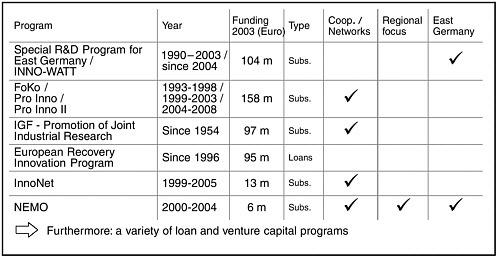

Innovation Policy Programs: BMWA

Next came a comparable table showing innovation-policy programs run by the BMWA (Figure 9), which, as mentioned earlier, is to some extent in competition with the BMBF. Heading the list is a program focused on innovation in East Germany, followed by the largest program in monetary terms, FoKo/Pro Inno, which targets collaborative work in innovation by SMEs. The next two programs were of similar size: The Promotion of Joint Industrial Research, a bottom-up research funding mechanism driven by industry and cofunded by the

FIGURE 9 Innovation policy programs, federal level: BMWA (selection).

SOURCE: Adapted from Federal Budget BMBF 2003, BMBF 2004.

ministry; and the European Recovery Innovation Program, which provides loans to innovating companies. Rounding out the table—which, like that for BMBA, is incomplete—are a pair of very small programs, InnoNet and NEMO, the latter an acronym standing for Network Management East Germany. Critics deride this profusion of programs in Germany as an “innovation-policy funding jungle” and claim that no one can understand it fully, a charge both ministries rejected. While acknowledging that, as a political scientist, he had his own ideas about the origin and development of this funding structure, Dr. Kuhlmann said that on the present occasion he would keep them to himself.

Programs Run by the Länder

Conceding that it would only deepen the complexity of the policy picture, he then turned to the Länder, which are responsible for funding and operating the nation’s universities, the latter traditionally receiving most of the research money available to the former for distribution. But the Länder are increasingly going beyond supporting university research to set up programs designed to:

-

spur technology development by funding both single-organization and cooperative R&D;

-

foster technology transfer, including transfer of personnel;

-

support startup companies by providing consulting, coaching, incubation, and financial assistance;

-

furnish venture capital and loan guarantees;

-

encourage patenting activities; and

-

participate in technology parks and incubators.

Huge differences in investment existed from state to state. But while, for example, Bavaria accounts for just over one-fifth of total nonuniversity research spending by the Länder and Saarland for a mere 0.5 percent, EU and other sources supplement funding in weaker regions.

Program Anatomy: Pro Inno

Dr. Kuhlmann chose two examples from this broad variety of programs to examine in detail. The BMWA’s Pro Inno, which had been running for more than 10 years and through which 630 million euros were invested in the period 1999-2003, has as its goal increasing the R&D capability and competences of SMEs. This is to be achieved through collaboration on not only a national but also an international level. By this he meant that German companies could receive money in support of efforts involving partners outside the country. Pointing this out as “an interesting feature” of the program, he said that “internationalization is now understood as a relevant part of future R&D policies.” Subsidies under Pro Inno run at between 25 and 50 percent of the cost of R&D personnel ranging across four program lines—cooperation with firms, cooperation with research organizations, R&D contracts, and personnel exchange—with multiple applications totaling up to 350,000 euros per firm allowed.

Since 1999, 4,850 firms and 240 research organizations have participated, with 4,000 R&D employees per year engaged in Pro Inno projects. A past evaluation in 2002 had shown that some three-fourths of participating firms would not have conducted the R&D had it not been for the program; Dr. Kuhlmann and colleagues were preparing an updated evaluation due later in 2005.

Considered one of Germany’s most significant R&D programs, Pro Inno is widely known and accepted among its target group. Its outstanding characteristics are its broad, open approach, high transparency, easy access, and relative lack of bureaucracy. The program receives a high number of applications—even though there is no guarantee of funding due to budget constraints and despite significant problems, during market entry.

Program Anatomy: InnoRegio

The second example, BMBF’s InnoRegio program, is aimed at strengthening the endogenous innovation potential of weak regions in eastern Germany by setting up sustainable innovation networks. A complex, “multiactor” program, it encompasses not only SMEs, large companies, and research organizations but also many other public and private activities and initiatives, funding both network

management and projects aimed at developing products and services. Run as a competition, the program has three stages: a qualification round in which ideas are solicited for potential networking initiatives (444 proposals were submitted in 1999); a development round in which the regions selected (25 of the 444) refine their concepts and projects; and a realization round in which the winners (23 of the 25) receive multiyear financial support for their initiatives.

The InnoRegio program is linked to an increase in innovation activities. In the prior two years, two-fifths of the firms selected by the program have received patents and almost all have introduced new products. Since 2000, 50 new firms have also been founded. But this last fact is less impressive in Dr. Kuhlmann’s judgment than, what he considered the program’s main impact—i.e., the creation of innovation networks across eastern Germany that comprises both public and private actors. Nevertheless, he noted that “in East Germany there is still a tendency to expect public funding to be the main source of stimulus towards innovation.” Moreover, although there is scant disagreement that networking is a basic precondition for innovation, the question of whether the impact of such initiatives will be sufficiently long-term, stable, and robust to justify the investment they require remains unanswered.

Germany’s “Partnership for Innovation”

Taking up a theme that Dr. Dahlman had earlier discussed in the U.S. context, Dr. Kuhlmann suggested that, in light of the variety of public policies affecting innovation, major countries may see the need to introduce some kind of coordination and collaboration across the agencies responsible for such policies. Germany’s current response, a federal innovation initiative, was born in October 2003, when Chancellor Schroeder summoned representatives of various stakeholders in the field—policy actors, public agencies, major companies, associations of SMEs, and major research organizations—to a forum where they debated challenges for the country’s innovation performance. In the aftermath, they created the Partnership for Innovation and started some longer-term “pioneering” activities. The overarching aim of this initiative’s broad agenda is to improve the framework for innovation in Germany through the collaboration of public and private actors.

The Partnership for Innovation had established a number of working groups of stakeholders, some of which Dr. Kuhlmann and his colleagues contribute to. “In some areas there is just talk, and they will continue just to talk,” he said. But “in some areas these working groups have actually started policy initiatives, regulatory [and institutional] reforms, and so on.”

Under the rubric of “High-tech Masterplan,” an effort is under way to ease access to venture capital; while some activities it comprised had predated it, a high-tech startup fund was kicked off only weeks before the symposium with 10 million euros, and is expected to grow in time. As the initiative grouped such a wide variety of activities, its efficacy will not be easy to evaluate, he said.

Germany’s Future: Threats and Opportunities

To conclude, Dr. Kuhlman provided an appraisal of the threats and opportunities Germany was facing, as well as a rundown of the federal government’s immediate priorities. He began his enumeration of the threats by emphasizing Germany’s high degree of dependence on its automotive cluster. Even if it had not hurt the country yet, this dependence is leaving Germany open to challenge in the longer term, particularly from East Asian competition. Second, he cited an anticipated shortage in the supply of highly qualified labor, especially in the engineering field. Like their contemporaries in the United States and East Asia, young people in Germany are not studying engineering and science in sufficient numbers. But Germany is also laboring under the problem of not having a big enough population of high-skill workers and of having had, until recently, regulations restricting immigration of engineers and scientists. Third, he reiterated that the country’s technological performance is losing momentum in some areas. Finally, he noted that public financing for the national science infrastructure is shrinking relative to financing coming from the private sector.

Nevertheless, Dr. Kuhlmann said, there were opportunities. The technological and marketing prowess of Germany’s automotive sector might allow it to turn the challenge it was facing to its benefit. Efforts were being made to build on the strong position that Germany, like other traditional EU members, enjoy in the growing markets of both Eastern Europe and East Asia. The country has an excellent science base in such advanced fields as biotechnology, chemicals, and nanotechnology. And its labor force remains highly qualified, at least in comparative terms.

The Potential of European Integration

Finally, Dr. Kuhlmann expressed his personal conviction that Europe’s integration, not in the political arena but in the area of research systems, could lend Germany’s national system huge potential. Possessed of the biggest research system in Europe, Germany has in the past tended toward both a domestic orientation and a degree of complacency. Increasingly, however, major research organizations and individual researchers alike are learning that they needed not only to collaborate on the European level, but also to reestablish themselves institutionally in a European context, if they wished to avoid overlap and to create new clusters of strength with worldwide visibility and potential. These developments were so recent that, he cautioned, some of the impressions he was conveying were still in the realm of speculation. While the single market offered significant opportunity, national governments, and particularly the German government, were yet to comprehend the existence of this potential and the difference between national and European. While this had been the source of some difficulties for those in charge, there was, he asserted, “no alternative to more collaboration and integration on this level.”

Identifying the immediate priorities for the German federal government, Dr. Kuhlmann said there is recognition of a need to improve linkages within the country’s fragmented research system, whose existing boundaries are rigid to the point that horizontal professional mobility was scarcely possible. Changes should, he recommended, be designed to take account of European integration as well. Meanwhile, work needed to reform the country’s university system with the goal of achieving international excellence has begun, although in his own opinion, progress has been slow compared to that observed in other countries, both within and outside Europe.

THE TEKES EXPERIENCE AND NEW INITIATIVES

Heikki Kotilainen

Tekes, Finland

Dr. Kotilainen expressed his appreciation for the opportunity to present Finland’s “small-country approach to innovation policy.” His presentation began with a very brief statistical overview, and continued with descriptions of Finland’s innovation system. He concluded with examples of the system’s achievements.

Before embarking on it, however, he would acknowledge a handful of factors that could be seen as drivers of change and, at the same time, challenges to be met. Various phenomena surrounding globalization discussed earlier are having quite an impact on Finland, as many companies move manufacturing and other operations to such countries as China, Malaysia, and Indonesia. Finland is also undergoing a very serious demographic change of the kind affecting all of Europe, a problem for which solutions are not yet become apparent. Sustainable development is another challenge commonly faced in the industrialized world, as is the management of knowledge and competence; in the latter, Finland, as a small country with limited resources, has to exercise great prudence.

Technology and networking are two drivers, or challenges, that Dr. Kotilainen viewed as one: When companies move, countries find themselves having to find new technologies to replace those that parted, while the companies, because they applied R&D independently of where it is performed, need to be on the lookout for technological and business alliances. Finally, he noted, change in the character and dynamics of innovation constitutes a challenge in itself.

Dr. Kotilainen noted that Finland is placed near the top of the world rankings in science and technology, second only to the United States. How could a small country whose only true natural resource are its people accomplish this? What had happened, he said, was that Finland’s industrial structure changed tremendously over the previous four decades. The pulp-and-paper sector, which accounted for a little more than two-thirds of the country’s exports in the 1960s, saw its share fall to below one-quarter by 2004, while exports in the electronics sector, including telecommunications, had taken off.

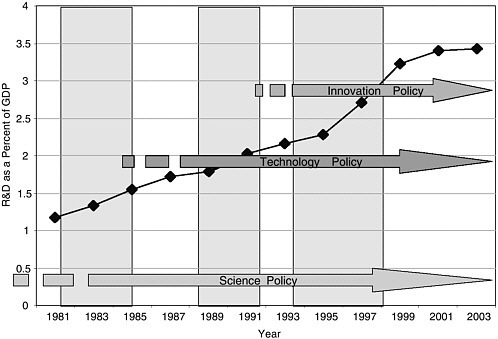

FIGURE 10 R&D/GDP in Finland, 1981-2003.

A major factor in this change, according to Dr. Kotilainen, has been “conscious and continuous investment” by Finland that has raised its R&D spending as a percentage of GDP from around 1.5 percent in 1985 to nearly 3.5 percent by the beginning of the current decade. Coinciding with this increase has been the evolution of Finnish policy in the realm of science and technology (Figure 10). Even though Finland’s science policies have been in place since the 1950s, technology policy formulation did not happen until the mid-1980s, following the establishment of Finland’s Science and Technology Policy Council. It was only after it began to implement technology policy that innovation policy appeared on the agenda. While Dr. Kotilainen attributed this progression to chance rather than to any special wisdom—and noted that, in fact, a similar evolution can be seen in other countries—he said that it had turned out to be a fortunate one. For innovation policy, had it made its appearance prematurely, might have been met by silence from the government and suffered a consequent loss of credibility. “You cannot,” he remarked, “jump from pure science to innovation immediately.”

Dr. Kotilainen pointed out that private-sector spending has shown the most growth since 1985 and has accounted for some 70 percent of the current total investment, which has been running at around five billion euros annually. Even so, the public sector has been the prime mover: Only when the government began

to take R&D seriously and increase funding for it did private investment follow. Still, when it comes to public funding for R&D taking place in companies, Finland is well below the Organisation for Economic and Co-operative Development (OECD) average at less than 5 percent of total corporate R&D spending. The position of some of the more highly ranked countries is, however, the result of heavy investment in military research, which Finland does not fund. The sector of the Finnish economy most active in R&D is electronics and telecommunications. Nokia alone accounts for something like 40 percent of Finland’s private sector, and while a small country can count itself lucky to have such a “behemoth,” the firm’s relative size could also be seen as a “threatening issue,” Dr. Kotilainen said.

Finnish Innovation System’s Institutional Structure

Turning from a quantitative to a qualitative portrait of innovation in Finland, Dr. Kotilainen identified the two main public organizations in the domain of R&D: the Academy of Finland, operating under the country’s Ministry of Education and charged with basic research; and his own institution, Tekes, operating under the Ministry of Trade and Industry and charged with applied research. Public-sector R&D actors also included universities; VTT, a large and multidisciplinary research institute under the Ministry of Trade of Industry; and other ministries, such as Agriculture and Forestry, that had their own research facilities. Providing direction to government institutions through achieving consensus on the growth of R&D is the Science and Technology Policy Council, which dates from 1986 and is, he said, “a very important element” in the Finnish system.

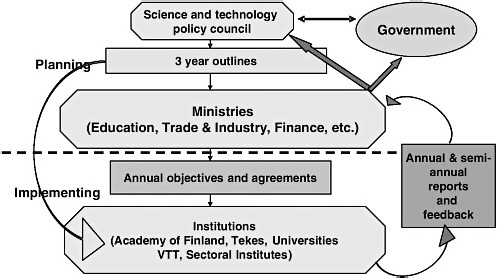

Understanding how the game of innovation was played in Finland demands an acquaintance with the Science and Technology Policy Council. Chaired by the prime minister, the council has as members five other cabinet ministers, including the minister of Finance; the directors general of the Academy of Finland, Tekes, and the VTT; and representatives of the universities, industry, and the labor unions. Every three years, the council issues an outline for science and technology; this outline takes the form of recommendations rather than regulations, something Dr. Kotilainen saw as strengthening Finland in comparison with the many countries where the government assumed an operational role. On the basis of the outline, institutions like Tekes work with the ministries to prepare annual objectives, which in turn become the basis for an agreement covering what is to be done over the coming year. The implementing institutions, after executing the plan, report to the ministries, which then report to the Council. Showing a schematic diagram of the process (Figure 11), Dr. Kotilainen pointed out that the spheres of planning and implementation were separated by a dotted line. “The operative part is operative and the planning is planning,” he emphasized. “They are not mixed.”

FIGURE 11 Planning and implementation of technology and innovation policy.

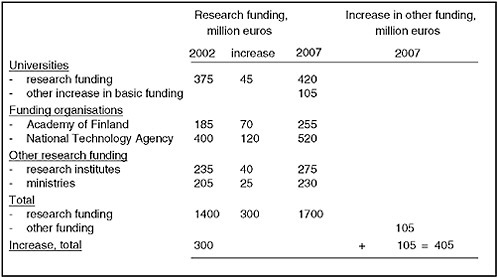

Implementation is left to the “expert organizations,” as he qualified Tekes, which might receive funding from the government but are free to act as they see fit. He then displayed a table providing details of an increase in funding for innovation proposed in 2002 for the five years that were to follow (Figure 12). While the Ministry of Finance was free to accept or reject such recommendations, it generally went along with those receiving strong support—and, as the table shows, the funding increase for innovation was already well under way.

For Finns R&D Is Investment, Not Expenditure

Having dealt with the system’s structure, Dr. Kotilainen took up the subject of its operation. In Finland, R&D funding is considered to be an investment rather than an expenditure. Money that goes directly from funding agencies to companies is seen as short-term investment; money that flows through universities and research institutes, creating technology and new skills that then contribute to companies’ competitiveness, is seen as long-term investment. The former route might require a few years at most, the latter a decade or more, but both types of investment are considered necessary. And not only that, they are considered one of the best investments the government could make, since they ultimately bring back sums 10 to 20 times their original size in the form of taxation.

FIGURE 12 Recommendations of the Science and Technology Policy Council of Finland relating to research and innovation funding.

SOURCE: Tekes.

Tekes’s Funding Strategy, Operations

Tekes itself has a steadily if gradually rising budget that reached 430 million euros in 2005. Research funding in the form of grants and company funding in the form of both grants and loans is distributed through a variety of instruments, such as national technology programs, direct company R&D funding, direct research funding of universities and research institutes, as well as equity funding for start-up entrepreneurs. Acknowledging the instruments themselves to be “very standard,” he placed emphasis on Tekes’s implementation. As networking and cooperation takes place between the companies and universities involved from the very beginning, all the instruments could be regarded as technology-transfer instruments. In fact, with the exception of TUPAS, a “little” program designed exclusively for SMEs, Tekes has no separate technology-transfer procedures. Private-sector entities are always required to provide matching funds when participating in university research, while companies receive credit if they invited universities to join research programs they had initiated.

In 2004, Tekes invested around 409 million euros, with 237 million euros going to companies—of which 31 million was in the form of reimbursable, reduced-rate R&D loans, 41 million was in capital loans, and 165 million was in R&D grants—and 172 million euros going to research institutions in the form of grants. In that year, about half of all funds were channeled through established technology programs while the other half went to individual, “bottom-up”

projects that were presented as unsolicited proposals by industry or research institutions.

Such applications are accepted at any time from either sector, but Tekes always considers whether they contained a component of cooperation between the two sectors. The established programs, seen as highly important to Finland’s general technology development, fund large projects featuring cooperation among multiple companies and universities or nonuniversity research institutions. The proportion of funding going through each of the two channels is not mandated by the government. In fact, the allocations vary year to year at Tekes’s discretion and depending on customer needs.

Placing a Premium on Cooperation

Although Tekes provides support on different terms under its technology programs (according to whether it was destined for public- or private-sector entities) this fact does not prevent projects from cooperating across sector lines. In fact, Tekes sees implementation of results from public research as dependent on parallel execution and networking with company projects, even to the point of pooling personnel.

In 2004, Tekes funded projects under 23 existing technology programs covering a wide range of emerging technologies having an overall value of 1.2 billion euros; such programs typically were of 3 to 5 years long and, in any given year, drew 800 separate “participations” from public research units and 2,000 from companies.9

That Tekes provides no more than 60 to 80 percent of the funding for university projects indicates that it always requires matching funds from industry, Dr. Kotilainen explained, adding that it generally refrains from funding projects at 100 percent even though it has the ability to do so. EU state-aid regulations limit support for private-sector projects to between 25 and 50 percent. Tekes’s decision-making and coordinating functions are guided by a steering committee chaired by a representative of industry. “We don’t let the professors be chairman,” he commented.

To carry out its functions, Tekes needs a facilitator in the form of national programs to link supply and demand, where supply is considered to be research and demand to be the enterprises. It is Finnish companies’ ability to articulate their needs, not just for the next year but over five years, that enables Tekes to design effective programs. “With our small resources we cannot do research for [the sake of] research,” Dr. Kotilainen explained. “It should be relevant to our economy.” Similarly, the level of the research funded is expected to be appropriate: “We cannot target a Nobel Prize in each field—that’s not for us.” Appropriate

|

9 |

For a list of current technology programs, see <http://www.tekes.fi/english/programmes/all/all.html#Ongoing>. |

goals, furthermore, help ensure that companies have the technology appropriate to their purposes and have the capability to absorb new technologies for their use. He named “this linkage, through the national programs, between research and the companies” as one of the reasons that Finland places “fairly high in the competitiveness statistics.”

Unique Features of Finland’s Innovation System

While it might depend on “normal” funding instruments, the Finnish innovation system boasts some unique features. First among these is trust among participants in the the university-government-industry “triple helix,” that by the early 1980s, enabled genuine and voluntary cooperation. Lack of corruption is a second advantage, although in Finland’s context “corruption” is likely too strong a word, said Dr. Kotilainen. “We don’t have to expend energy to avoid fraud in the system,” was how he rephrased it. A third factor is consensus and the Science and Technology Policy Council helps ensure a high degree of agreement, which in turn enhances implementation. A fourth factor is cooperation. Tekes and the Academy of Finland work very closely together, helping make possible simultaneous funding of universities and companies, and thereby the coupling of research with development. Such efforts extend beyond science to the coordination of technological development with social development, a “very important” consideration, he said, as the country “cannot leave part of the population to be dropouts [when it comes to] technological development.”

The small number of actors in Finland’s system, with its consequent simplicity and “holistic” quality, constitute another advantage. Tekes itself enjoys a very high degree of independence from the cabinet and the ministries in assessing projects and making decisions on funding, both of which it is free to do independently in-house. Its experts working on assessments have access to industry and research leaders, and, like all the institution’s employees, possess knowledge of both the domestic and international markets suited to their responsibility over international cooperative efforts.

Impact of Tekes’s Activities

Besides the increase in R&D investment, the system has helped generate a remarkably sharp increase in high-tech exports’ share of Finland’s total exports, from below 5 percent in 1988 to over 20 percent beginning in 1998. To be seen specifically among corporate R&D projects funded by Tekes is a prevalence of cooperation. Networking—whether with SMEs, foreign corporations, or research institutes and universities—is occurring in around 80 percent of all efforts, as a result of which Finland leads the EU in intercompany cooperation.

Coinciding with Tekes’s investment of 409 million euros in 2004, Dr. Kotilainen stated, 770 new products have reached the market and 190 manu-

facturing processes have been introduced. The institution also claims to have contributed to 720 patent applications, 2,500 publications, and 1,000 academic degrees at the bachelors, masters, and Ph.D. levels in that year. According to a 1999 study of public financing’s effect on companies’ innovation activities, conducted by VTT, the receipt of funding from Tekes often causes project goals to be reset higher than they had been initially. This study also concluded that Tekes funding allows for the expansion or acceleration of projects, the latter being of particular importance in sectors where the first company to market takes all. A study by Finland’s National Audit Office dating to 2000 found that Tekes funding allowed not only broader and more rapid implementation of projects, but also surmounting of risk barriers: 57 percent of projects considered in the study would simply not have been undertaken without support from Tekes. Finally, a pair of 2003 studies by the Research Institute of the Finnish Economy (ETLA) found increased corporate R&D investment to result from public investment in research and not the other way around.

Innovation: More than Research

Returning to the challenges accompanying globalization and other changes in the nature of innovation, Dr. Kotilainen observed that, while research is important for radical or disruptive innovations, most innovation is incremental and not necessarily rooted in research. When it comes to user-based innovations, the customer is paramount. The tendency for manufacturing to merge with services is an important development. Smaller firms are more directly engaged in innovation itself, while large companies, he implied, are more involved at the level of application. The growth in importance of multidisciplinary research underlines the value of alliances and other forms of cooperation. For these reasons, the public and private sectors need to innovate together.

Dr. Kotilainen concluded with a brief assessment of the implications of these challenges for his own institution. The role of the innovation agency is changing along with the landscape, a development that requires serious thought about the future. No longer regulators, agencies like his have to become instructors, he said. “We are not a referee [but] should be a partner in this process; we are not a system integrator but a networker; [we are] not the finance provider but [an] investor.” This, in turn, demands a big change in the mindset of the agency, which should no longer be “only an administrator” but “should be innovative as well if we ask innovations from our customers.”

CONVERTING RESEARCH TO INNOVATION

Peter J. Nicholson

Office of the Prime Minister, Canada

Dr. Nicholson expressed his desire to clarify at the outset that, as chief of policy in the office of Canada’s prime minister, he is not specifically charged with management of science and technology. Although experienced in the field as a former faculty member at the University of Minnesota, he had never administered science and technology programs in government. Much of what he was about to say, therefore, was distilled from large quantities of good advice he had received from people dealing directly in such matters.

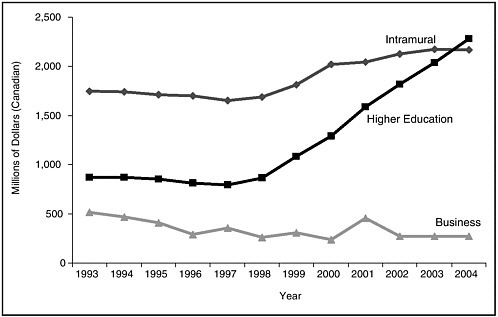

As he judged it unnecessary to explain why Canada should be concerned about science-and-technology and innovation policy, Dr. Nicholson immediately began crafting a statistical portrait of the country’s R&D efforts. In this, he explained, he would be aided by graphics showing amounts in U.S. dollars that had been converted from Canadian dollars at the purchasing-power parity of roughly 85 U.S. cents to a Canadian dollar. On a chart tracking Canada’s gross domestic expenditure on R&D as a percentage of GDP in the 10 years from 1993, he pointed out a steady upswing in spending that peaked with the end of the tech bubble in 2001. The ensuing downturn could be attributed to a fall-off in R&D spending by business, particularly in the information-technology sector and more particularly by Nortel.

Higher Education Funding “Remarkably High”

Canada’s current total R&D spending is around $19 billion a year. Business enterprise expenditure on R&D accounts for around 55 percent of the country’s total, government intramural expenditure on R&D for around 12 percent; the remainder comes from higher education expenditure on R&D, which, at a “remarkably high” 33 percent, places Canada atop the G-7 and third among OECD nations. “Otherwise we’re down in the middle of the pack,” he said, “notwithstanding the increase [in Canada’s R&D spending] over the years. The point is that the bar has been rising.”

Even if Canada does not post world-leading ratios of R&D expenditure to GDP, its overall economic performance suffices to make it the second wealthiest among mid-sized countries in the OECD based on GDP per capita and second in the G-7 as well. Much of the technical dynamism in the Canadian economy is due to its unique level of integration with the U.S. economy. “In many, many sectors, there is one economy,” said Dr. Nicholson, adding that “a great deal of technical sophistication in the Canadian economy is embodied in imported capital.” To illustrate, he noted that a North American car buyer is unlikely to know whether the Chevrolet, the Chrysler, or even the Toyota he or she was buying is manufactured in Canada or the United States.

Fiscal Consolidation Opens Gate to Innovation

Contributing to Canada’s positive performance is a fiscal consolidation that has taken place over the previous 13 years. Canada’s fiscal problems had been rapidly growing out of control, but in 1995—for reasons that, according to Dr. Nicholson, remained “a little mysterious”—Canada “got an incredible dose of fiscal religion, which has continued to this very day.” The federal budget went into the black in 1997 and has stayed there, unlike in the other G-7 countries, which have all gone back into deficit. This turnaround has permitted the Canadian government to make numerous choices that up to that point it has not been able to make, chief among which is a determination to fortify the microeconomic foundations of the economy. Traditionally, Canada’s economy has been resource based, with a great deal of industrial power added through its integration with the United States. “If we wanted to have something that was home-grown and that could give us a degree of independence,” he explained, “we had to build our innovation capacity from the ground up.” It was this effort that would be treated in the rest of the presentation.

Dr. Nicholson projected a graph tracing the evolution of federal spending on R&D in Canada (Figure 13), which demonstrates the “paradigm shift” in federal support for higher education that coincided with the federal budget’s going into surplus. Federal support for R&D in the business sector has trended down in real terms over the same period (somewhat more than indicated in Figure 13, which takes no account of inflation.) Although support for intramural R&D within the federal system has risen, research has been overwhelmingly outsourced to higher education, primarily to the university and the research hospital systems.

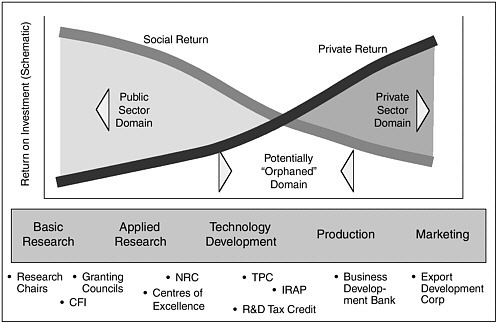

A Policy Conundrum: Private vs. Public Return

To help explain the public-policy rationale for supporting different kinds of activities related to innovation, Dr. Nicholson displayed a chart representing a spectrum running from basic research to such unquestionably commercial activity as marketing (Figure 14). The relative rate of social return declines as one moved rightward from the left-hand end of this chart. There is, nonetheless, some private return at the left-hand end, and perhaps even a great deal in the case of ideas protected by patents. Conversely, some social return occurs at the right-hand end of the chart owing to spillovers. But what he described as a conundrum for innovation policy focused on a “potentially ‘orphaned’ domain” near the middle where it is difficult to discern which of the two types of return is higher; the ambiguity of their relation to one another has occasioned such policy arguments as the one, alluded to earlier, concerning Sematech.

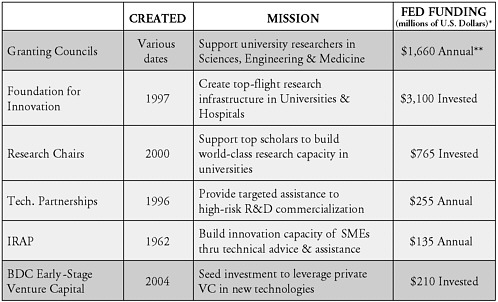

Canada’s federal government is active all along this continuum through many dozens of programs, some of them quite large. These include the Canada Research Chairs (CRCs), the Canada Foundation for Innovation (CFI), Technology Partnerships Canada (TPC), and the Industrial Research Assistance Program

FIGURE 15 Federal support for innovation: Examples.

NOTE: Federal funding is labeled annual in some cases and in others covers the investment for the full period. (*)—Purchasing-Power Parity estimated at USD 0.85 per CDN dollar. (**)—Includes indirect costs of research and graduate student support.

(IRAP). But before turning to describe them, Dr. Nicholson estimated that the R&D tax credit generates a benefit of $1.5 billion to Canadian corporations conducting research. In cases of companies that are not publicly traded, he specified, these credits are refundable, so that benefits are not available only to firms that are turning a profit.

Posting a table containing data on his four selected programs (Figure 15), Dr. Nicholson noted that with the sole exception of IRAP, founded in 1962, they date from the previous decade. Still, all have enough experience that conclusions about their performance can be drawn. Pointing to the column that presents amounts of federal funding, he called attention to the fact that the Foundation for Innovation has invested the largest amount at $3.1 billion, and that the university research granting councils distribute just under $1.7 billion a year.

Canada Foundation for Innovation (CFI): Building Leading-Edge Infrastructure

CFI, the first of the four programs to be described, was set up to cofund leading-edge research infrastructure in universities and hospitals in response to a precipitous mid-1990s decline in the quality of research infrastructure in

Canadian universities—“another evil consequence,” in Dr. Nicholson’s words, “of the fiscal problem that the country was mired in.” This foundation, which is government endowed, receives a grant worth a total of $3.1 billion in two or three installments; of that, it commits $2.5 billion to fund 4,000 projects through competition-based awards that are limited to 40 percent of project costs. In addition, there are special funds to encourage first-time researchers—a part of the program that has proved to be “extremely popular and high-leverage.” There are also funds to help operate facilities, a “critically important” function because many advanced infrastructure components require highly technical operational assistance. Finally, funds are available to finance international collaboration. CFI’s board, although it includes some government appointees, operates at arm’s length from the government.

The objectives of the Canada Foundation for Innovation are fourfold:

-

to transform research and technology development in Canada;

-

to foster strategic research planning in universities, which Dr. Nicholson called an “interesting objective” and said had been “brilliantly achieved”;

-

to attract and retain world-class researchers, something that was taking place as well, as he would demonstrate with figures in a moment; and

-

to promote collaboration and cross-disciplinarity, which he called “a huge success” of the program.

“The bottom line,” he declared, “is that if you want to work at the leading edge, you need to have tools at the leading edge.”

Fostering Strategic Research Planning

CFI’s selection process begins with proposals that come almost exclusively from universities and research hospitals. These proposals are required to fit with an institution-wide strategic research plan at the applicant institution. Dr. Nicholson described the evaluation criteria as “fairly predictable”—research quality and need for infrastructure; contribution to innovation capacity building; and benefits to Canada. In a two-tier review, applications are grouped by subject matter and sent first to experts in their specific field, then to a multidisciplinary committee with the ability to make cross-area comparisons.

This selection process has forced institutions to develop long-term research plans and set priorities, in some cases for the first time. Its most significant consequence, in Dr. Nicholson’s view, is that it has improved the quality of applications. Proposals worth $1.4 billion, a large percentage of them “absolutely top-drawer,” were presented in the latest selection round even though the funding available covered only one-quarter of that sum. Every round, in fact, has raised the bar, with projects becoming larger and more complex. “While you would have expected that, once the low-hanging fruit was picked, the program might

start running out of energy,” he commented, but “exactly the opposite has happened.” Collaboration among institutions has multiplied, research excellence has been stimulated at smaller universities as well as large, and most provinces have been led to establish similar programs at their own level. The latter are allowed to contribute to the 60 percent of complementary funding required by CFI, which has produced a “huge multiplier effect” within Canada’s innovation system and has started to “put Canadian research opportunities on the world map.”

A Virtuous Circle: Collaboration and Upgrading

CFI has “triggered a virtuous circle of collaboration and upgrading,” Dr. Nicholson said, asserting that “strength begets strength.” But, at the organizational level, he added there are three other lessons:

-

CFI’s arm’s-length institutional structure and governance make its decisions credible to the point of being virtually unassailable, “not an easy thing to do in modern democratic systems.”

-

The endowed-foundation model has enabled CTI to plan beyond annual budget cycles. “They know how much money they have,” he commented. “They always want more, but at least [they] know what [they’re] playing with.”

-

The incentives are right, so that if the objectives of the foundation are met, further government funding is expected. Such funding is “not necessary, because this is an endowment,” he said, “but the board and the people who run this program understand what they have to do.”

Still at issue, however, is the level of investment that is appropriate for CFI. “At what point do you stop?” he asked. “Or do you keep following this bootstrapping process to higher and higher levels?”

Canada Research Chairs: Complementing Infrastructure with Talent

A human-resource complement to CFI is the CRC, whose objective is to develop a cadre of world-class researchers to exploit the infrastructure built up under CFI. CRCs’ 2,000 chairs support all subject domains; 1,400 are filled to date. The potential number of chairs allocated to each university depends on the proportion of research grants it wins in other national competitions, although a bonus is reserved for smaller institutions.

The CRCs are divided into two tiers. The first, for world leaders in their disciplines, is an award of seven years’ duration, renewable indefinitely, at $170,000 in support per year; winners in this category have access to numerous other kinds of support as well. The second, for “exceptional young faculty,” provides support for 5 years at $85,000 per year that was renewable just once, for another 5 years. Under the selection process, universities are expected to nominate candidates for

the CRCs in line with the same institution-wide strategic research plan to which CFI applications need to conform. Winners are selected by a three-person review panel or, in the absence of a consensus among panel members, by a standing interdisciplinary adjudication committee. The approval rate has been running at 85 to 90 percent of submissions, and acceptance by those approved has been around 95 percent.

CRC’s outcomes have been extremely positive. At first, universities tended to nominate their best faculty in hopes of keeping them—although the program did not, as it turned out, inspire significant poaching among institutions. The focus has since shifted to recruitment, evidenced by the fact that, more recently, about 40 percent of chairs have been awarded to nominees from outside Canada. The relationship between the winning of research grants and the potential number of chairs has increased general interest in both; more specifically, the CRC program has significantly improved the research capacity of smaller universities. Together, CRC and CFI have “powerfully boosted Canada’s research capacity at the front end,” Dr. Nicholson stated. The only cloud over CRC’s success has been the underrepresentation of women, who hold only around 15 percent of chairs reserved for world leaders and 20 percent of chairs overall. “To some extent that may be a factor of age demographics still,” he speculated, adding, “It’s something the program managers are very concerned about.”

Assistance to Industry: IRAP

Moving from support for basic research to support for industry, Dr. Nicholson next described the IRAP, which he called “the classic one in Canada for small-business innovation.” Its funding, about $135 million a year, underwrites the activities of 260 Industrial Technology Advisors operating from 90 sites across the country who are available to all small businesses engaged in technology. About one-third of IRAP’s budget goes to consulting advice, which absorbs about 50 percent of these specialized advisors’ time; about two-thirds, 30 percent of which is subject to repayment, goes to project support. The scope of project support is quite broad, encompassing everything from feasibility studies and precompetitive R&D to international sourcing and youth hiring.

Of 12,000 clients served annually through the program, only 20 to 25 percent receive funding; the average level of such support is $30,000 per year, the maximum $425,000. Still, those 3,000 projects have encouraged formation of a network of 1,800 subcontractors, among them suppliers, consultants, universities, even the National Research Council. Dr. Nicholson called project approval “very fast”—2 weeks for projects under $12,000, up to one month for those up to $85,000. While pronouncing himself cautious about accepting existing evaluations of multipliers for IRAP spending, he quoted estimates as high as $12 in downstream investment for every dollar of spending on IRAP help, and up to 20 to 1 in sales or an equivalent. “The main point here,” he said, “is that this is a real

body-contact sport: These are people all over the country engaged face-to-face with small businesses.”

One lessons from IRAP is that cost recovery for technical advisory services is unlikely to work. “Companies will not pay for what they don’t know,” said Dr. Nicholson, relaying wisdom from the program’s director. Other noteworthy observations follow:

-

The consulting industry values IRAP advisors as prescreeners and referral agents and, seeing its relationship with IRAP as symbiotic, has not complained about the program.

-

The selection of sectors and topics of programs at this level needs to be client-driven.

-

Proposals are better assessed as and when they are received rather than in request-for-proposal batches, as the former procedure fits with the firm’s innovation cycle and also avoids peak-load processing problems.

-

More focus is needed on mid-sized SMEs, those with 100-500 employees.

-

Increasingly, SMEs need to be connected with national and global innovation networks.

TPC: Risk-Sharing and “Repayability”

The purpose of Technology Partnerships Canada, which has functioned as the Defense Industry Productivity Program until 1996, is to risk-share industrial research and precompetitive development across a wide spectrum. Designed to address a “persistent and frustrating” gap in Canadian firms’ development of new technology, it covers from 25 to 30 percent of the costs involved in R&D, development of prototypes, and testing. In addition to significant cofinancing by industry, it features repayability, which depends on results. Targeting firms of all sizes and partnering with IRAP for SMEs, TPC parses its activities into three rather broad sectors: aerospace/defense, which, if considered separately, raise the number of focus sectors to four; environmental technologies; and “enabling” technologies, including biotech, materials, and ICT.

Only the program’s budget, about $250 million per year on average, imposes a limit on the size of individual projects. From 1966 through 2004 about $2.3 billion has been committed, a little over one-third of that amount to SMEs—which, however, account for 90 percent of the 673 projects supported. Three-fifths of all funding goes to the aerospace and defense sector. Dr. Nicholson said that, according to “fairly careful calculations,” private-sector recipients have matched TPC investments at an average ratio of 4 to 1. Project selection, which at 12 to 18 months takes much longer than in the case of IRAP, begins with the screening of applications, usually taking the form of “skeleton outlines,” by in-house experts. Winners at that stage are invited to submit full proposals, which become

the object of detailed due diligence. Negotiation then follow, where repayability and intellectual property provisions are among the major items covered.

Criticisms from Public and Participants

Dr. Nicholson then identified a number of “conundrums” raised by TPC that he judged “fairly characteristic” of such programs. Chief among these, perhaps, are those centering on repayability. This feature has been “oversold a bit,” creating expectations among the public that have not been met. “Only about 3 percent of the funds out the door have actually come back so far,” he stated. “But the truth is that we knew there was a long lead time for the repayment to come back; and, in fact, the program managers claim that repayment is on schedule.” Compounding the issue, designing repayment terms that properly reflect the program’s risk/ reward-sharing component has been very difficult, since it was usually impossible to track what portion of a company’s returns has accrued exclusively to a project supported by TPC.

The selection process has been another source of criticism. For one thing, project approval is protracted. For another, a perception exists in the political arena that TPC has been too focused on large companies—in particular, those in the aerospace sector—although the great majority of awards have in reality gone to SMEs. In addition, program objectives are so broad that it is difficult to maintain a consistent approach—or, put another way, there are so many grounds for approval that it is sometimes difficult to justify turning a project down. “That tends to invite a lot of objections from people who were disappointed,” Dr. Nicholson said, “because someone can always find a precedent and say, ‘But you approved that one, so what’s wrong with me?’”

“What Does It Mean to Capture National Benefits?”

As “probably the most fundamental question” arising from the TPC experience, however, Dr. Nicholson cited the following: “In a world of global supply chains, what does it really mean to capture national benefits with programs like this?” Observing that many of the program’s customers are multinationals—past TPC recipients include IBM, Pratt & Whitney, and RIM—he declared that it was “not quite clear that one can capture the benefits [for a national economy] to the extent that one once could.”

Summing up, Dr. Nicholson expressed the opinion that Canada has rapidly built a strong basic research capacity that is paying off in terms of reputation and reversal of the country’s brain drain. Its technology-development programs have evolved from subsidy-oriented to more sophisticated risk-sharing models, recalling a similar evolution in Finland. Finally, the lesson of Canada’s experience, and one that he had seen reiterated throughout the morning’s talks, is that any national innovation strategy today has to be globally linked.

DISCUSSION

Having commended the speakers for being on target in their presentations, and noting that he had taken over as moderator from Mr. Knox, Dr. Wessner called on Mark Myers to open the questioning.

The Special Demands of German Integration

Dr. Myers asked Dr. Kuhlmann to assess innovation programs in Germany since reunification from the time perspectives of the former East and West, as well as to look at economic growth in eastern Germany and to compare it with that seen in Poland, the Czech Republic, and Hungary. He expressed a specific interest in the equalization of salaries that took place right at the moment of unification in Germany, remarking that the other countries enjoyed, during at least part of their own restructuring, the “advantages of lower wages.”

Dr. Kuhlmann replied that the question had been debated in Germany as well, but that historical circumstances had left no alternative. The East European countries, having become EU members, were gradually availing themselves of the opportunities offered by “a European research system that is growing together.” Salaries there had been relatively low 10 years ago but were slowly rising as those countries integrated with the European network. Thanks to this integration, he added, Eastern Europe can expect to develop advanced national research infrastructures in the longer term.

Germany’s path had been different. Sudden integration caused a breakdown of the existing East German research system, which had not been compatible with that in the West. A marked brain drain resulted from salary discrepancies between the two regions: Especially early on, industrial researchers from eastern Germany found work with companies in western Germany and made their way there. Eastern Germany, meanwhile, was (and still is being) kept alive by huge public investments, without which there would be inadequate employment.

Innovation Policy—Also on the Demand Side?

Egils Milbergs of the Center for Accelerating Innovation, observing that most of the commentary from all three panelists had concerned enhancing innovation inputs—“more R&D, more scientists and engineers, more capital, etc.”—suggested that a full discussion of innovation policy should include the demand side as well as the supply side. He urged consideration of macroeconomic policy’s impact on innovation, specifically the role of interest rates; how tax policy affects the demand for innovation; standards; trade policy and how nations integrate with global markets; procurement policy; and competition policy. “It seems like there’s an entire domain with huge influence on innovation that people who talk about national innovation systems don’t really address in a meaningful way,” he

asserted. “They give recognition to these factors, but when you look at what the policies are, it’s all about enhancing input, not maximizing output.”

Canada: Political Obstacles on the Demand Side

Dr. Nicholson registered his agreement, saying that in his general policy role he probably spent more time on the demand side than on the supply side. But he allowed that, with the exception of tax cuts, the supply side is more visible politically because of the complexity of many demand-side issues, trade policy and competition policy being examples. Having spent most of his career in the private sector, he personally viewed competition as paramount: “Necessity is the mother of invention, there’s no question about that,” he said. “At the companies I’ve worked in, we were at our most inventive when the competition’s breath was at our heels.” This reality had been particularly salient as competition, once largely domestic, became global; finding a response to what was both a new source of demand and a challenge would occasion “a lot more head-scratching in all governments.”

Against this backdrop, Canada has worked hard on its macroeconomic fundamentals, first getting control of monetary policy, then moving to fiscal policy. Amid massive tax cuts, its corporate tax rate is now down to below that of the United States. More recently, under a “smart regulations initiative” fueled by recommendations from a blue-ribbon panel for improvements in such areas as drug approval, the country has started to eliminate “the little differences that don’t make a difference” but nevertheless interfered with trade across the U.S.-Canada border. Another area ripe for streamlining—admittedly, “a very dangerous word”—is environmental regulation. But while ample “low-hanging fruit” in the regulatory area offer ways in which “government policy [could] be helpful on the demand side of the equation,” he said, “none is easy politically.”

Germany: Trying To Go Beyond Classic Recipes

Dr. Kuhlmann also pronounced himself in agreement with the statement that far more elements of public policy have an impact on innovation than those included within the “narrow notion of innovation policy.” As understanding of this area grew, European governments were more frequently becoming the object of criticism that their innovation programs did not take account of broader economic issues. Those formulating innovation policy, meanwhile, are finding themselves obliged to design their initiatives in the context of other policies whose impact on “what actually happens in companies” might be greater by far. Discussion of these questions is increasing in numerous European countries, Germany among them, although the debate is limited to experts rather than taking place among the general public.

Former Chancellor Schroeder’s Partnership for Innovation was an attempt at a systemic or holistic approach to influencing the basic conditions of innovation that went far beyond classical policy instruments. But, speaking from his experience with governments at different levels in Germany, Dr. Kuhlmann saw a problem in the prevalence of competition among agencies. Unlike some competition, this variety is not productive; rather, being rooted in claims by each agency that its work was more important than that of the others, it results in gridlock, “quite a mess from the perspective of innovating companies.” Some degree of coordination, including some effort at mutual information and collaborative design, is therefore necessary.

In Finland, perhaps, designers of demand-oriented innovation policies ask “What is the problem, and what can we do about it?” rather than occupying themselves with the borders among ministries. Only at the end of the design process might they ask, “Who is in charge of what, and how would we have to redesign structures?” This sequence does not, however, represent the norm in public policy making in Germany.

Cross-Border Comparisons of Attitudes, Programs

Dr. Wessner then posed three questions that, although quick in the asking, he judged likely to demand lengthy responses. He requested that Dr. Nicholson, whom he complemented on a superb presentation, discuss how the Canadian government had dealt with what sounded like charges that some of its innovation programs were vehicles for corporate welfare that funneled the majority of available funding to large companies. Referring to the STEP Board’s assessment of the U.S. Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) program, which was in progress, he described himself as having been heartened to hear that someone—in this case, Dr. Nicholson—shared his acquaintance with the difficulty of ascertaining the consequences of a single award for the future of a company.

He then asked Dr. Kotilainen whether he regarded the budget of the United States’ Advanced Technology Program, which had been running at around $140 million per year, as adequate to the U.S. economy in light of the fact that Finland, a nation with 5.1 million inhabitants to the United States’ 300 million, was spending between $530 million and $560 million annually on a very similar program.

Finally, Dr. Wessner said he had observed that while Europeans enthused over the creation of a European research space and innovation system, they often had barely concluded when they began speaking about their own national programs. He asked Dr. Kuhlman to talk about those two elements in relation to one another, then very briefly to discuss the impact of the EU programs, a subject Americans were very interested in, and to assess whether innovation efforts in Europe are primarily driven at the EU or national level.

Parrying the “Corporate Welfare” Charge

Dr. Nicholson said that, as charges of corporate welfare are still to be heard, the problem that Dr. Wessner alluded to is yet to be solved. Because subsidies to business have been cut “pretty dramatically,” however, he felt that “just in terms of the gross dollars” the critics could no longer make as strong a case. Canada’s federal budget surpluses had also ameliorated the situation, by rendering the trade-offs less obvious. A more substantive change, the move to risk-sharing with repayability as featured in the Technology Partnerships Program, had placed a new obstacle before opponents of the programs, although they nonetheless took the line: “You haven’t gotten all your money back yet, so obviously this must still be corporate welfare.” Also helpful is that, increasingly, potential criticism is arising in the context of a local facility where a large number of jobs are at stake. Then, “frankly, the political shoe is sometimes on the other foot,” Dr. Nicholson said, for “if there isn’t a little bit of big-company support, there’s a larger price to pay.”

Administering Supply-, Demand-Side Policies Separately

Dr. Kotilainen began his response by taking up the issue of demand-side measures in support of innovation that Drs. Nicholson and Kuhlmann had previously addressed. At Tekes, he said, innovation policy is viewed as far broader than most other policies implemented by the government, including science policy, technology policy, and industrial policy. And because it incorporates elements of all the others, innovation policy is difficult and complex to run. “Therefore, we think we should concentrate on that,” he said, “leaving the other policies to the private sector or to other parts of the government to take care of.” Even though Tekes finances research, the main focus of its awards is always industrial competitiveness and networking, a strategy that leaves the rest to the companies themselves.

Addressing the matter of the Advanced Technology Program (ATP), Dr. Kotilainen emphasized its philosophical similarity to Finland’s national innovation programs. Those programs have been extremely beneficial for the country because they combine the skills of its universities with those of its companies. Projects are planned jointly by the universities and industry from the very beginning, so that both know exactly what to expect from the research, and companies also got acquainted with university researchers, a very good basis for subsequent recruiting. This, he remarked, is an essential function no matter what the size of a country is. On the specific subject of ATP’s annual budget, Dr. Kotilainen recommended that, rather than being cut, it should be favored with the addition to the end of a zero or two.

Balancing Europeanization, National Programs

Dr. Wessner, announcing that the luncheon speaker had arrived and that the session would thus have to be concluded quickly, asked Dr. Kuhlmann to be brief in his remarks on the relationship between Europeanization and those national programs still in place within the EU.

Dr. Kuhlmann said he had speculated in a paper published just two weeks before on how “this very contradictory relationship,” so fraught with tension at that moment, might develop in the future.10 There were some government officials who are opening up to collaboration across borders; there is, in fact, a program called ERA-net that funds only those intergovernmental collaborations aimed at developing joint national programs on a European platform. At the same time, however, other officials still fail to see the value of such efforts, whose very existence, at least partially, call into question their role as national policy makers.

|

10 |

J. Edler and S. Kuhlmann, “Towards One System? The European Research Area Initiative,Edler and S. Kuhlmann, “Towards One System? The European Research Area Initiative, the Integration of Research Systems and the Changing Leeway of National Policies,” Technikfolgenabschätzung: Theorie und Praxis, 1(4):59-68. Accessed at <http://www.itas.fzk.de/tatup/051/edku05a.pdf>. |