3

Economics, Ethics, and Employment

During the workshop, speakers and participants considered the economic and ethical driving forces for a green building agenda, and the concept of expressing organizational ethics in building design. This chapter summarizes presentations from three speakers: Gregory Kats, John Poretto, and George Bandy. These speakers described current research and provided insight based on their personal observations and experience. Future goals and research needs in this area are discussed.

GREEN BUILDING: ECONOMICS

Businesses embrace the idea of green buildings because they believe they are ethical, productive, and healthy, noted Gregory Kats of Capital E. The primary driving forces are quality of life and health. He remarked that many American corporate headquarters (e.g., Goldman Sachs, Reuters, New York Times, Bank of America) are building green facilities, often more proactively than other sectors, such as government, residential housing, and academia.

Building a green facility involves following guidelines, such as Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED), the nationally recognized green building rating system developed by the U.S. Green Building Council. LEED is not an exact science, but rather a consensus-based approach to defining practical criteria for green building. LEED is the current best practice standard for the building sector, although it is somewhat subjective in its criteria. For example, energy professionals believe that energy is underweighted, and those in the water field believe the same is true for water. Because of this, it is important to quantify the benefits objectively, asserted Kats.

A recent study aggregated the cost and financial benefits of 33 green buildings (Kats and Capital E, 2003). Although commissioned for California, it had a national focus. In general, the study reported that the initial construction cost

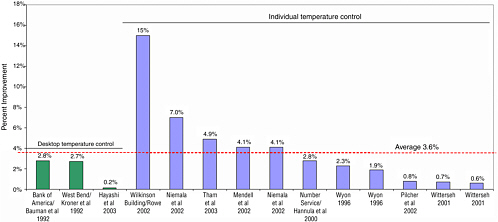

FIGURE 3-1 The average cost premium associated with building green for U.S. buildings certified at the LEED Silver level has generally decreased over time. This is primarily due to familiarity with the process and the requirements of being LEED certified.

SOURCE: Modified from Kats and Capital E (2003).

was higher for green buildings—approximately 2 percent, or $3–5 per square foot—than nongreen buildings, noted Kats. However, he suggested that some of the cost premium can be attributed to the novelty of building green and the fact that many builders are on a learning curve. Construction costs decline as more green buildings are constructed and familiarity with green design increases, and when green building principles are incorporated early in the design process. For example, the average cost premium for a green building certified at the LEED Silver level has generally decreased over the past 10 years (Figure 3-1). An important message for institutions that engage in their first green building is that their next green building is likely to cost less, said Kats.

Health and Productivity Are the Drivers for the Benefits of Green Facilities

When quantifying benefits, Kats’s group focused on areas with the largest potential gain. Rent or amortized ownership account for approximately 5 percent of operating costs, and the direct and indirect costs of employees constitute 80–90 percent. Thus most studies look to this area of productivity and health for the largest impacts.

In a financial benefits summary of green buildings (Table 3-1), the study found that energy benefits saved $5.80 per square foot, while operating costs saved approximately $8.50 per square foot. For productivity and health, four

TABLE 3-1 Financial Benefits of Green Buildings—Summary of Findings (per square foot)

|

Category |

20-Year Net Present Value |

|

Energy savings |

$5.80 |

|

Emissions savings |

$1.20 |

|

Water savings |

$0.50 |

|

Operations and maintenance savings |

$8.50 |

|

Productivity and health value |

$36.90–55.30 |

|

Subtotal |

$52.90–71.30 |

|

Average extra cost of building green |

(–3.00 to –$5.00) |

|

Total 20-year net benefit |

$50–65 |

|

SOURCE: Kats (2003). |

|

drivers were measured: lighting control, ventilation control, temperature control, and the amount of daylighting. These four drivers are a subset of a larger number of factors that affect productivity and health. For buildings certified at the LEED Certified and Silver levels, productivity and health increased about 1 percent. For buildings certified at the Gold and Platinum levels, the increase was about 1.5 percent or 7 minutes of employee time saved per day, noted Kats. The largest cost for a public or a private entity is the cost of its employees; these numbers translate into a net saving of $34–55 per square foot, depending on the level of certification. He concluded that an initial cost premium of $3–5 per square foot results in a net return of $50–65 per square foot net over a 20-year period at a 7 percent discount rate (Kats, 2003). There were additional significant financial benefits that the study was not able to quantify, including insurance, employment, equity, security, and brand appreciation.

Green Schools

Another recent study that gathered objective information on green buildings examined the costs and benefits of 30 green schools (Kats, 2006). Although the data came from a national sample of schools, the energy costs and teacher earnings were calculated on the basis of Massachusetts-specific costs. Both the conventional and the green school buildings averaged approximately 125,000 square feet for 900 students. The average cost premium for the 30 green schools in 10 states nationally was 1.65 percent, which translates into a cost premium of $3–4 per square foot. The study results showed an energy savings of 33 percent and a water savings of 32 percent (Kats, 2006). There were also substantial academic gains. In one example, two conventional schools were combined into a newly constructed green school in North Carolina. For the three years prior to the move, only 60 percent of the students achieved state-level standards on mathematics and

reading; after the move, the proportion rose to 80 percent. The only changes were the introduction of good daylighting, ventilation control, temperature controls, and control of pollutants; the students, teachers, and parents remained constant (Kats, 2006). A reduction of approximately 15 percent in colds and flu was also observed. Overall, the study found a benefit-to-cost ratio of 20 to 1 in green schools.

Determining the impact of green schools on the health and performance of students is an important area, but the research has lagged. The Kats report was among the first to analyze the benefits in this area. Subsequently, the National Research Council (NRC) published a report entitled Green Schools: Attributes for Health and Learning. The charge to the NRC committee was to “review, assess, and synthesize the results of available studies on green schools and determine the theoretical and methodological basis for the effects of green schools on student learning and teachers’ productivity” and to look at possible impacts of green schools on student and teacher health (NRC, 2006).

The committee found that a number of factors made the task more complex than might first be evident. These included the lack of a clear definition of what constitutes a green school; the difficulty of measuring educational and productivity outcomes; the variability and quality of the research literature; and confounding factors that make it difficult to isolate the effects of building design, operations, and maintenance. In addition, most inferences about the impact of the built environment on health and performance are based on studies of adult populations. Committee members noted that extrapolating from these studies to younger populations is difficult. In its review, the committee “did not identify any well-designed, evidence-based studies concerning the overall effects of green schools on human health, learning, or productivity,” noting that this is understandable because the concept of green schools is relatively new and evidence-based studies require significant resources. The committee did find sufficient scientific evidence to establish an association between some aspects of building design and human outcomes, including acoustics and learning, excess moisture and health, and indoor air quality and health. Additional findings and recommendations on the state of research on the building envelope, indoor air quality, lighting, acoustics, ventilation, and the transmission of infectious diseases are included in the report.

Health and Productivity Gains

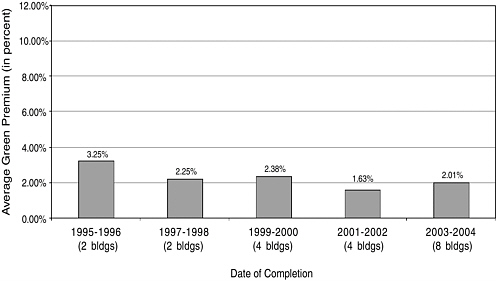

A review of the literature by the Carnegie Mellon University Center for Building Performance found a range of productivity gains related to both improved temperature control (Figure 3-2) and high-performance lighting systems. Kats observed that one of the characteristics of high-performance green buildings is that they typically have more sophisticated energy management systems and better integrated lighting strategies. He noted that the Carnegie Mellon group also

found health benefits from improved indoor air quality. Improvement in indoor air quality was linked with an average reduction of 41.5 percent in symptoms.

A study by the real estate firm of Cushman and Wakefield (RICS, 2005) surveyed 12 owners of public and private green buildings to determine what they thought were the most significant effects attributed to building design. Health and productivity benefits of working in a green building outranked the benefits of decreased energy consumption and operating costs. Kats views this as another indicator that the real estate community recognizes health and productivity as driving forces, although they are harder to measure than reduced energy and water consumption.

In another survey, Turner Construction (one of the largest construction firms in the country) asked 719 executives to rate the benefits of green buildings compared with nongreen buildings (Turner, 2006). Of these executives, 60 percent worked at organizations currently involved with green buildings. The survey covered a number of categories, including building value, worker productivity, return on investment, rents, occupancy rates, and retail sales. Overall, the executives rated the benefits of green buildings very highly, and those with more direct experience with such buildings were more positive in their responses. For example, of executives involved with green buildings, 91 percent believed that these buildings improved the health and well-being of occupants, compared with 78 percent of executives not involved with green buildings. Similarly, 65 percent of executives involved with six or more green buildings said the residents or occupants enjoy “much greater health and well-being,” compared with 49 percent of executives involved with three to five green buildings and 39 percent of executives involved with only one or two green buildings.

Kats pointed out that green buildings are a fundamental part of addressing global warming because of their energy efficiency. There are opportunities to invest in energy-efficient technologies, such as energy-recovery ventilators and ground source heat pumps. Overall, Kats emphasized that building green is a good news story. The more experience that various sectors have with green buildings, the more costs come down. He suggested that people will increasingly recognize the benefits of building green as they continue to gain experience with these buildings.

ETHICS OF GREEN BUILDINGS

John Poretto of Sustainable Business Solutions explained that the Hill-Burton Act triggered a wave of hospital construction beginning in the 1950s. Today, many buildings from that era are becoming obsolete and are scheduled for replacement. Poretto questioned why we are building facilities that only last 40 to 50 years and that lack flexibility and adaptability. He suggested that it might be time to look for a new paradigm.

Poretto drew on his experience as the executive vice president and chief

operating officer for the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston to illustrate his points. During this time, the university owned a 4- to 5-year-old building of approximately 850,000 square feet. It was the second most expensive building to operate in the state of Texas, and within four years of its construction, the Texas State Department of Health declared it a sick building. Recognizing that the university had one of the state’s largest, most costly, and most dysfunctional buildings caused him to look at green buildings in a more pragmatic, ethical, and holistic manner.

The University of Texas Health Science Center embarked on constructing a state-of-the-art green building for its nursing students with the goal of teaching them early in their careers about the benefits of building green, as well as instilling an appreciation for the green healthcare facilities in which they are likely to work during their careers. The building was financed primarily with fees assessed to students. The state legislature and the philanthropic community contributed, although Poretto noted that it was primarily the students’ commitment that made this new approach possible.

Architectural Style Denotes Commitment

Poretto drew on the writings of Hippocrates, in particular an essay entitled, “The Physician,” which explores the basic ethical standards and actions by which a doctor should live. In this essay, Hippocrates maintained that “the dignity of a physician requires that he should look healthy, and as plump as nature intended him to be; for the common crowd, consider those who are not of this excellent bodily condition to be unable to take care of others.” Poretto questioned why an essay that later espouses ethical ideals, such as honor and trust, opens with a focus on the doctor’s physical appearance. He interpreted this idea to mean that the first thing a patient encounters during a medical consultation is the physician’s physical appearance and bearing, which provides important insight about the physician’s health, health behavior, and trustworthiness. In an analogous way, when people visit an organization, the first attribute they notice is the building that houses it. For those who learn and work in clinical and health education institutions, the design and architecture send crucial daily messages about the institution’s identity and values and about attitudes toward the health and productivity of the building’s occupants.

Poretto asserted that most healthcare buildings do not convey a message of humanistic concern for the welfare of others. He called for a more “principle-centered” and responsible operational model, one that reflects the highest values of both donors to, and leaders of, health institutions. This model requires attention to a healthcare facility’s purpose, use, design, construction, and maintenance, and it needs to extend holistically from staff within the institution outward to the community as a whole.

Poretto focused attention on the tax-exempt status of many healthcare institu-

tions, a status that reflects an institutional obligation to serve the good of the community as a whole. A tax-exempt institution’s mission has a higher meaning than that of profit. If, indeed, it is the goal of healthcare institutions to serve human needs and well-being, then an understanding of how best to meet expectations is necessary, asserted Poretto. The leaders and the people selected to carry out this lofty mission should be competent and compassionate and possess an ethical purpose that grounds their leadership. High objectives and relevant standards must be set for selecting people who lead and work in the facilities, noted Poretto. He suggested that the organization’s actions cannot be based on values different from those that are taught to students or applied to patients. These expectations support the notion of green healthcare facilities.

Long View of Ethical Principles

Building green facilities does not stop with the organization; it also requires a holistic view of its operations, noted Poretto. He pointed out that organizations should work with entities that share and complement their ethics, visions, and principles. As tax-exempt orga

Decisions guided by short-term considerations lead to preventable problems and costs, which are usually far greater than their preventive measures.

—John Poretto

nizations, these entities must be held accountable for creating and maintaining principle-centered operations and for behaving in ways that demonstrate wise expenditures. Poretto asserted that decisions guided by short-term considerations lead to preventable problems and costs, which are usually far greater than preventive measures.

What it means to be green or sustainable and how that is consistent with the expectations of a tax-exempt status start with a multigenerational viewpoint. The principal difference between ethics and policy that focus on the individual and ethics and policy that focus on the institution is the latter’s multigenerational potential and perspective. He noted that this requires constructing buildings that have the capability to span generations. He emphasized the need for early discussion of several issues, including how to gain the greatest efficiency from the natural surroundings, how to take advantage of daylighting and natural breezes, protection from inclement weather, and so on. Poretto asserted that green buildings accomplish this because they use natural materials, are flexible, and are multigenerational in their approach. Higher education and healthcare associations have outstanding yet currently underrealized opportunities for bringing about volume pricing breaks and providing support for smaller companies to offer competitively priced green goods and services. He concluded by saying that buildings of healthcare institutions should be seen and evaluated not only as a functional elements of work and symbols of social or artistic standing, but also as an ethi-

cal statement by the institutions. This statement should demonstrate concern and responsibility for the well-being of the building’s users and the community.

INCREASING WORKPLACE PRODUCTIVITY

George Bandy of Interface Research stated that business may have framed the phrase “worker productivity” too narrowly. The sciences connected to productivity are ergonomics, cognitive psychology, social psychology, cultural psychology, ecology, biology, economics, leadership, and management. Ergonomics and cognitive psychology relate to the I. Social psychology and cultural psychology relate to the we, and economics, leadership, and management relate to the they. He asserted that the challenge is to convert the they to the we. The I and the we are the users and the occupiers of the building. He suggested that the industry sector needs, through creativity and learning, to identify the population that they are servicing. Interaction and dialogue are essential to this effort. The challenge is to determine what should be researched, for whom and why, and what should be taught now so that in the future professionals are well prepared. He suggested that careful studies of human behavior are needed, the design of which should focus on goals, health, and productivity.

The commitment to sustainable development is an ethical decision requiring a conscious choice to provide for the needs of present and future gen

A strategy is needed that inspires more sustainable behavior, not just good intentions.

—George Bandy

erations, noted Bandy. The challenge is to develop a strategy that creates healthcare professionals who recognize and choose to create ecologically sound technologies for healthcare institutions and the communities they serve. He suggested that a strategy is needed that inspires more sustainable behavior, not just good intentions. An individual’s behavior is influenced by his or her knowledge of facts and the values and norms of his or her environment. The primary mission is to cultivate knowledge in students and practitioners so they can care for the health needs of individuals. A central focus of recent research is the influence of the environment on the health and wellness of individuals and communities, observed Bandy.

Environmental health relates to more than the natural environments of air, water, and land; it also encompasses the built environment, noted Bandy. The environment in which one trains employees, negotiates contracts, and performs surgery reveals much about society’s collective human principles. He asserted that a company cannot profess to be genuine in its aims for worker productivity, health, and well-being if it conducts business and provides services for clients and facilities that are unhealthy and economically wasteful. Bandy asserted that workplace environment matters, noting that there are five key factors in terms of

the working environment: personal space, climate control, daylight, office design, and quiet facilities. He concluded that the evidence suggests a need for sustainable development, especially for healthcare facilities, and further suggested that developed countries can provide leadership in sustainability and serve as a model for developing countries.