5

The Process of Change

The process of change from traditional building to incorporating green building practices can be viewed as a moving target that evolves with the institution and the current state of knowledge. To understand the process, one should identify who or what the institution is, how the process of change began, why the process started, and what the challenges are, noted Bahar Armaghani of the University of Florida. During the workshop, these concepts were discussed in terms of the commitment to change building practices at the University of Florida and at Emory University.

UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA

The University of Florida has an ecological footprint of approximately 2,000 acres, more than 300 held in conservation. The campus has approximately 1,900 buildings with a combined total of 20 million square feet. Approximately 49,000 students attend the university, which employs approximately 800 staff. The University of Florida is essentially a city within a city, with ownership of the utilities distribution system, wastewater treatment plant, and so on, noted Armaghani. The university pays approximately $2.7 million for electricity and $85,000 for water each year. The facilities generate about 18,000 tons of waste annually for basic operations. During home football games, an additional 9 tons of waste are generated at the stadium, and 7 tons from the tailgating events across the campus, explained Armaghani. As a small city, the University of Florida believes that it should be responsible for its use of resources.

What Are Sustainable Buildings?

According to Armaghani, sustainable buildings meet high standards in siting, orientation, design, construction, and energy efficiency—and all of these elements

Sustainable buildings meet high standards in siting, orientation, design, construction, and energy efficiency—and all of these elements are measurable.

—Bahar Armaghani

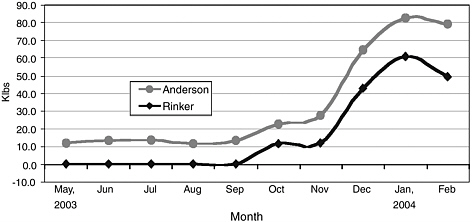

are measurable. Sustainable buildings are better for the environment and their occupants than nonsustainable buildings. This can be illustrated by comparing similar buildings after construction. For example, of two buildings on the University of Florida campus of similar size and functionality, the green building is approximately 37 percent more efficient (Figure 5-1) than a building that employs standard construction principles. Premium costs incurred during construction are recovered with the savings accrued by operating a sustainable building.

Why Sustainable Buildings? Health, Economics, and Environment

From a visit to the Department of Energy and the U.S. Green Building Council websites, one can appreciate the studies that illustrate the negative impacts of buildings on the environment, including the amount of energy consumed. The university knows there are environmental, economic, and productivity benefits to erecting sustainable buildings. During the workshop, there were discussions about improving the quality of air, water, and the environment in general, observed Armaghani. She noted that people spend an average of 80–90 percent

FIGURE 5-1 In comparison to traditional building standards (Anderson building), a LEED-certified building (Rinker) was 37 percent more energy efficient. These buildings are of similar size and functionality. Because buildings have a life span of approximately 100 years, the saving can be greater than any premium costs during the building phase.

SOURCE: University of Florida, Facilities Planning and Construction (2005, unpublished).

of their time inside buildings, and this provides motivation for institutions to minimize environmental and health impacts. Adopting the Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) initiative was an important strategy for the university. Among other benefits, building sustainably gave the university a positive environmental image, elevating it to a position of leadership in the field, said Armaghani.

Sustainable buildings have lower utility bills, enhance assets, and increase value. She explained that the first building certified at the LEED Gold level cost the university about 7 percent more than a traditional building, but the expense was recovered in approximately 10 years. With an average life span of approximately 100 years, the university considers the initial capital investment in green buildings to be justified, noted Armaghani.

Armaghani observed that building sustainably provides benefits to public health, including improved air quality, minimized strain on infrastructure, and enhanced quality of life for building occupants and the community. Sustainable buildings also have productivity benefits, such as decreased absenteeism and staff turnover. The University of Florida strives to recruit and train the best staff and wants to provide an environment to retain this talent. She observed that a happy employee is often a productive employee, and this fosters staff retention. The improvements in productivity are not limited to staff, but also impact student performance, noted Armaghani.

Although building sustainably may be the right thing to do, the primary reason the university pursued this course was its commitment to education, explained Armaghani. The university wants to train leaders and encourage them to make a difference in the world. She believes it is the university’s responsibility to ensure that students gain knowledge and expand this field on local and global levels. The university is empowering students to make decisions that benefit the environment and future generations.

University of Florida Sustainability Plan

Since 2001, the University of Florida has officially pursued LEED certification for all major renovations and construction projects. The university projects ranged in cost from $3 to $85 million, and this major commitment required evaluation of data and construction standards, noted Armaghani. These standards are important because there is a limited budget to maintain a building once constructed. The University of Florida was among the first institutions to require LEED accreditation of its staff. With this preparation, staff were empowered to take leadership in the building design process, to ensure that contractors and consultants understood the university’s requirements, and to secure the best value for the money.

Armaghani noted that 14 of the 35 LEED-certified projects in the state of Florida are in the University of Florida system. Although the first buildings were

designated for health research and medicine, newer facilities include the school of engineering, the school of law, the library, and a number of technology centers. The university has changed the construction culture on campus—suppliers, contractors, and consultants who want to work with the university must be familiar with the LEED process. The University of Florida helps shape the construction culture in the surrounding community, said Armaghani.

She observed that a number of programs facilitated this transition for the university. First, the university committed to using reclaimed water for irrigation. Second, mass transit was incorporated into the program to accommodate the large student population. Finally, the university has shown its commitment to conservation by setting aside 300 acres to remain undeveloped. These efforts help to shape future programs in sustainability, noted Armaghani.

The University of Florida has gone beyond LEED standards by committing to additional construction standards, such as Energy Star roofing, tree preservation, and waterless urinals. The installation of waterless urinals alone may

In a pilot project, the university started purchasing or contributing to green power for two buildings and has offset about 1.5 million pounds of CO2 emissions. This is the equivalent of taking 124 cars off the road and planting 194 acres of mature trees.

—Bahar Armaghani

save up to 40,000 gallons of water per year per urinal, said Armaghani. This is a tremendous benefit for the environment and makes economic sense, she added. Other innovations include harvesting rainwater for flushing toilets and using photosensors to determine occupancy in a room. Most raw materials used in the buildings come from within 500 miles, which reduces transportation emissions. The university is also committing to green power to reduce its environmental footprint. In a pilot project, the university started purchasing or contributing to green power for two buildings and has offset about 1.5 million pounds of CO2 emissions. She said this is the equivalent of taking 124 cars off the road and planting 194 acres of mature trees.

Challenges of Implementation

Armaghani noted a number of internal and external challenges to the implementation of sustainable building. The internal challenge was institutional change. People accustomed to the way they performed their work needed convincing that the available data and cost benefits warranted change in procedures. The perception that LEED-certified buildings cost more money was another challenge; however, costs were reduced by the in-house LEED administration. Armaghani explained that steep learning curves caused the initial buildings to be more expensive than later projects. She added that the university learned a number of lessons

along the way, and it continues to learn. A key step was gaining understanding of how to work within the sometimes arduous LEED certification process. The university assigns a LEED coordinator to oversee the project through the process. External challenges were posed by contractors, subcontractors, and consultants who were unfamiliar with the LEED process and required training.

EMORY UNIVERSITY

Wayne Alexander of Emory University observed that—much like the University of Florida—Emory University has not encountered significant conflicts with sustainable building. Because the university is an urban campus in

Because Emory University is an urban university in the heart of a residential area, there is general agreement that commitments to the philosophy and concept of sustainability are appropriate not only for the good of the university proper, but also for the community at large.

—Wayne Alexander

the heart of a residential area, there is general agreement that commitments to the philosophy and concept of sustainability are appropriate not only for the good of the university proper, but also for the community at large, said Alexander. Emory has undertaken many sustainability initiatives, but these have been less formal than current plans, noted Alexander. The Emory environment was originally conceived as a forest in which students walk across campus under its canopy. Although part of the canopy has suffered over the years, there are still large areas of virgin forest on campus. The current plan aims to preserve this original concept.

Sustainability Vision

Alexander credited university leaders with taking a significant role in establishing the original vision and implementing the sustainability initiative at Emory. The sustainability vision was codified in a document that states, “We seek a future for Emory as an educational model for healthy living, both locally and globally—a responsive and responsible part of a life-sustaining ecosystem.” From this vision, the university has focused considerable effort on human health, which is reflected in five primary themes of the vision:

-

A healthy ecosystem context

-

A healthy university function in the built environment

-

Healthy university structures, leadership, and participation

-

Healthy living, learning, and working communities

-

Education and research

The university has established effective programs to meet these goals, noted Alexander. One such initiative is the Institute for Predictive Health Care—a joint project with the Georgia Institute of Technology. The institute is dedicated to maintaining health rather than simply treating disease, and it has devoted considerable time to discussing that concept. What occurs in its hospitals is ultimately defined by what is occurring in the community, observed Alexander. The university insures 10,000 direct employees as well as another 20,000 people and their families. Sustaining their health is a prime institutional consideration.

Need for a Sustainable Vision

Alexander remarked that the rise of obesity and type II diabetes is an epidemic of potentially catastrophic proportions in the United States. He described this as a problem of “too’s”: people eat too much food of poor quality and exercise too little. The need to address this epidemic from a preventive point of view is reflected in Emory’s sustainable vision. The objective, said Alexander, is to make the campus a model for healthy living and to convey this message to anyone who visits the campus. He explained that the goal of all the education programs is to transform Emory graduates into ambassadors for sustainability and healthy living.

The case for sustainability began some years ago when Emory embarked on a LEED pilot program. The initiative was fully supported at the highest leadership levels within the university, including the board of trustees. A number of reasons for adopting LEED were articulated:

-

Supporting the environmental mission of the university

-

Providing the framework for high-performance buildings

-

Providing third-party validation of the sustainable vision

-

Making good business sense by using life-cycle analysis and not first-cost analysis to make decisions on equipment and building fixtures

-

Providing leadership and educational opportunities on sustainability

-

Being good stewards of the environment

LEED at Emory

The Whitehead Research Building was the first building on campus to be certified at the LEED Silver level. Coming in ahead of time and slightly under budget, it exemplifies how to use sustainable architecture to ensure health, noted Alexander. The university’s commitment to LEED-certify all of its buildings is demonstrated by the 11 LEED projects currently registered at Emory. The university is approaching 2 million square feet of space that is being designed with the LEED program.

The Winship Cancer Center was the university’s first experience in building a

green healthcare facility, noted Alexander. As a primarily outpatient-based center, it did not pose the challenges of inpatient facilities and their attendant complexities. Alexander remarked that the building is quite appealing as a place to work, with a reliance on natural lighting.

LEED has been an effective way to analyze the environmental impacts of a project, including energy usage predictions, observed Alexander. The cost of a LEED building for Emory has been 0.5–2.0 percent above traditional approaches, and the payback has generally

Going beyond LEED, Emory strives to incorporate sustainability into its operational and academic endeavors.

—Wayne Alexander

occurred in the first few years of a building’s operation. Going beyond LEED, Emory strives to incorporate sustainability into its operational and academic endeavors. The university is continually developing both a strategic and a master plan. These plans address such issues as traffic flow problems, stormwater runoff, energy conservation and the development of alternative energy, and reduction of the university’s ecological footprint. Traffic flow problems go beyond Emory’s border and require partnerships with the county, neighborhood associations, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the American Cancer Society. As a result of its commitment to a holistic approach to sustainability, Emory has adopted a plan that

-

calls for all facilities to be certified at the LEED Silver level at a minimum;

-

is an integral part of the Emory University Sustainability Initiative;

-

allows the sustainability commitment to inform planning but not limit growth;

-

directs all facilities to support healthy lifestyles—not only among the ill, but also among the well who work at or visit the campus; and

-

emphasizes health preservation guided by the Emory/Georgia Tech Institute for Predictive Health Care.

Because of the relatively large size of the healthcare industry in the U.S. economy, it can make a highly favorable impact on human health by minimizing its ecological footprint. This can be accomplished if health care institutions fully embrace and adopt sustainability principles in general and especially in facility construction, concluded Alexander.