Participatory Irrigation Management: A Case Study from Turkey

M. Fatih Yildiz

Agricultural Engineer-Contract Manager

EU Central Finance and Contracts Unit

In 1993, State Hydraulic Works (DSI), the main agency responsible for large scale water works initiated a program to transfer management responsibilities to users, with support of government and World Bank. With the transfer of operation, maintenance and management responsibilities, financial responsibility for routine O&M expenses were also taken from the state. This amount can now be allocated toward state irrigation investments (ERDOGAN, F. C. 2003). Water Use Associations (WUAs) manage 91% of irrigation systems constructed by DSI. Performance indicators such as irrigation ratio, irrigation efficiency, collection rate of fees and others are now better than before the transfer programs. Although the transfer program has encouraged good management, operation, and maintenance of irrigation systems, some problems have been seen regarding administrative, legal and managerial aspects of WUAs. Judicial problems are currently among the key problems, especially in the GAP (South Eastern Anatolian Project) region. In addition to those problems, political and coordination issues need to be solved. Some problems which are common in almost all Mediterranean countries include weak coordination among institutions dealing with irrigated agriculture and few qualified technical staff, major constraints to sustainable water resources management.

Another problem is the inappropriate use of technologies that result in inefficient irrigation and maintenance systems (KORUKÇU, A, 2003). In order to achieve efficient coordination and management of irrigation, committees at the regional level should be established to set priorities for irrigation investments considering local conditions while ensuring the full participation of users. The committees could serve as a kind of bridge to convey problems from the ground to decision makers and provide feedback and support to the WUAs in the process.

Participation of farmers should be considered the most essential factor for better management of irrigation systems. Although, substantial efforts are given to participation during the transfer process, participation should be encouraged earlier in order to create ownership among farmers. At the present time the participation of farmers starts with completion of construction. Training of farmers on management, operation and maintenance should be carried out before the transfer process.

INTRODUCTION

Projects for the development of water and land resources are still the most important investment projects in Turkey. In order to obtain optimum yield from irrigation projects, appropriate planning, design, management, operation and maintenance are essential. Greater socio-economic development is possible by taking measures to increase the value of irrigation investments and for high quality and profitable production (OZKALDI, A., et al, 2003). Since water and land resources are limited, most of the effort should focus on efficiency. Although Turkey has a significant potential to develop water and land resources as compared with some other Mediterranean countries, there are important financial, physical and socio-economical

constraints. Irrigation projects are costly to construct and require funds for operation, management and maintenance to achieve the goals and maximize agricultural benefits from irrigation.

Irrigation Development

There are two main agencies responsible for irrigation investments the DSI and the General Directorate of Rural Services (GDRS)). The responsibilities of this Directorate have been transferred to the Ministry of Agriculture and to governors where DSI is responsible for water resources with discharges larger than 500l/s. GDRS is responsible for discharges of less than 500l/s. DSI is in charge of the development of soil and water resources and putting these resources into use and for public benefit. DSI plans, designs, and constructs irrigation systems, and also defines general principles and policies for irrigation management. DSI either takes direct responsibility for irrigation management units or transfers the responsibility to other organizations. GDRS deals with land reform, on farm development projects such as drinking water and roads and transfers its irrigation system responsibilities to cooperatives. The irrigation area developed by the two agencies until 2003 is presented in table 1. As it is seen from the table, the biggest portion of irrigated area, 2,340,197 ha, has been developed by DSI where GDRS has developed 1,002,238 ha of land.

TABLE 1 Irrigation Development (01.01.2003), DSİ 2003

|

DSI |

2 340 197 |

|

GDRS |

1 002 238 |

|

Farmers and others |

1.000.000 |

|

Total irrigated area |

4 342 435 |

Administrative Structure of Water Use Associations (WUAs)

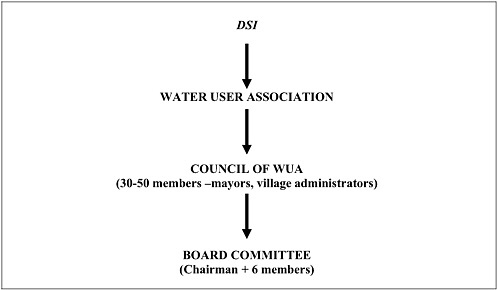

Since WUAs manage the biggest portion of irrigation areas (91% of the area developed by DSI is managed by WUAs), it is important to understand their organizational structure in relation to other organizations. WUA consists of several villages. DSI identifies WUA boundaries and prompts village administrators to apply by preparing the WUA statute in a standard DSI format and submitting it to the General Directorate of Local Administrations of the Ministry of Interior. WUA can make amendments in the statute by taking decision to the council. The Council (Figure 1), typically with 30 to 50 members, consists of mayors and village administrators (Muhtar) as ‘natural members’ and a number of ‘selected members’ depending on the service area. The Board committee typically has seven members. The General Secretary and Accountant are Board members, and the remainder are elected as Council members for a year. The Chairman is elected for one to four years term. DSI is an observer member during the election of chairmen.

The key actor is the General Secretary, as he is responsible for technical implementation and management of WUAs’ projects. He is the second person in terms of ranking positions. He is expected to communicate with other institutions and organizations. One of the most important problems is the weak link among extension services, decision makers, and the final users in

water management. There is need for institutionalization among all these stakeholders so that the problems can be transmitted to the decision makers through WUAs when they occur at the farmers’ level, since the WUAs are the closest organization to farmers and work together with farmers on daily duties.

FIGURE 1 Water User Association.

Some Problems of WUAs

The main problem after transfer is inequitable water distribution for the first years. As WUAs get more experience, this problem decreases year by year. Inequitable water distribution occurs due to water shortages, mistakes made assessing crop water requirements, the impact of powerful big land owners, a tendency of chairmen to favor their relatives and mismanagement and inadequate maintenance work. WUAs in the western part of the country work more efficiently than some WUAs in the other parts of the country. The success of WUAs depends mostly on the chairman’s management capacity. If the chairman is educated and has managerial skills, the WUAs work smoothly even when they have old irrigation facilities.

WUAs’ staff needs training especially on water distribution and irrigation plans. Although they have some experience on these issues, they do not know some of the technical aspects of irrigation as in the case of Harran Plain. General Secretaries and water distribution technicians are very experienced in water distribution and regulating water in canals, but often they do not understand crop water needs at the beginning of season. Their entire water request depends on the size of the irrigated area not on crop patterns, thus they do not have true records regarding to

water distribution. They measure water only when there are conflicts with DSI on allocated water and need to check with WUA from main canals which are under responsibility of DSI.

WUAs do not have monitoring systems that reveal problems and can improve planning for the future. They have records on budgetary issues and collection of water fees, but they do not have a management information system that can be used as database.

Inefficient use of water at the farm level is another problem. WUAs can not intervene with farm level activities as the nearest organization to farmers. The limited capacity of WUAs does not allow them to provide direct support to farmers at on farm level although some WUAs have written in their statute that they will support farmers in agronomic and crop protection issues. WUAs can be supported by providing staff that are available when needed, from governmental institutions. Thus, WUA can play a bridging role between farmers and institutions. In this regard WUAs can have an agricultural “extension unit” constituted within WUA office building.

Farmer participation in the transfer process is enhanced somewhere at the beginning of the establishment of WUA. Towards the end of the construction’s completion works, there is little time before irrigation. Although DSI puts most of its efforts on establishing of WUA rather then providing farmer participation in earlier stages before implementation, in some cases DSI contracts with construction companies for training of WUA staff on operation and management of irrigation systems, especially in pumping systems.

Most WUAs who have taken on responsibility for the management of new irrigation schemes do not adequately deal with system maintenance. They do not allocate the 30% of their budget to maintenance as is suggested in the statute. Instead they allocate something like 0.5-1.5% (BEYRIBEY; M, et al, 2003). They should be required to establish the operational and maintenance units within their framework.

Future Perspectives

Irrigation investments are carried out very slowly due to limited budgets. All investment costs are compensated by DSI at the present time. Since the government has budget constraints and can not allocate more money for investments, beneficiaries should share a small part of the cost after they take over the responsibilities of irrigation. They can collect this share together with water fees. The share compensated by beneficiaries could then be transferred to construction works.

There is no common solution for all regions. Each region may have different problems, different circumstances, and social structures. A national committee for each region should be formed to play a coordinating role between the national government and beneficiaries so that problems can be directed to the appropriate institutions and government. Agency participation of beneficiaries will be easier through national committees. Coordination is always a problem among related institutions and WUAs, as well as other organizations. It is also a problem in institutions that deal with irrigation issues. For instance, land consolidation and on farm development should parallel irrigation project implementation. GDRS having responsibility for on farm development and land consolidation may not have a sufficient budget to perform the work while DSI may

have enough funds to continue construction work. Thus, farm development work may be completed long after irrigation systems are finished. In this case, irrigation efficiency becomes a serious problem.

Training of WUA staff remains an important issue not only for water distribution but also for irrigation at the farm level. Most training activities for WUA staff focus on water distribution purposes. Since WUA staff is among the closest people to farmers, they should be trained on irrigation at the farm level and on agronomic aspects. DSI could remain the trainer of WUAs for irrigation planning and O&M activities. The agronomic aspects are generally neglected.

DSI should lead the establishment of the federations of WUAs to manage the main canals. Management of the main canals is still hard work and may not be carried out by DSI. DSI should gradually move away from management of the main canals.

CONCLUSION

Turkey has been involved in participatory irrigation management activities for more than ten years. WUAs have gained experience in the management, operation and maintenance of irrigation systems. Now, they are faced with “second generation problems” stemming from legal and political constraints. In terms of water distribution and collection of water fees, WUAs do not have serious problems because WUA staffs have become more skillful and capable. Although it will not solve all the problems, the draft law for WUAs should be enacted as soon as possible.

Areas to be transferred should cover large areas that may not be more economical to manage. WUAs having responsibility for small areas with many farmers may not be able to cope with conflicts among farmers. Water fees are estimated based on an area principle, so that as the area gets smaller the income of the WUA gets smaller, and at some points that income may not meet expenditures. The biggest portion of WUAs’ income comes from water fees (85%). The rest comes from member fees, fines and penalties. The last three items are not collected regularly, thus all WUA incomes generally come from water fees. As the service area increases the income increases.

Water pricing should be estimated in realistic ways and approved by the WUA councils. The WUA budget does not represent the real costs of WUAs (UNVER, O, Gupta, R, K 2002). At the present time, WUAs consider water fees of neighboring WUAs in their estimates so that they do not exceed the amount identified by neighbors; hoping to avoid farmers’ complaints and allowing the reelection of the chairman. Thus, water fees often remain far below the real amount. Therefore, some WUAs are faced with budgetary problems. The estimated amount by WUAs should be ratified by DSI in order to have realistic prices.

Despite all of these constraints, Turkish experiences in participatory irrigation management can be a model for some countries. DSI has achieved the transfer activities without increasing the number of staff; in fact it has had a decreasing number of staff.

References

Beyribey, M., et al. 2003. Integrated approach in agricultural water management, II. National congress on irrigation, Page 350, 16-19 October, Aydın, TURKEY

Erdogan, F., C. 2003. Water Saving in Mediterranean countries workshop, Participatory management activities in Turkey, 15 December 2003, Sanliurfa, TURKEY

Korukcu, A., Buyukcangaz, H. 2003. National water congress report, Holistic approach to water and irrigation management, page 24, 16-19 October, Aydın, TUREY

Ozkaldi, A., et al. 2003. II. National congress on irrigation, Importance and comparison of Irrigation projects in Turkey, page 164, 16-19 October, Aydın, TURKEY

Tekinel, O. 2003. Water Saving in Mediterranean countries workshop, Turkish experiences on participatory irrigation management, 15 December 2003, Sanliurfa, TURKEY